Blender 3D: Noob to Pro/Procedural Eyeball in Cycles

Knowing before Making

[edit | edit source]Blender is a powerful and complex 3D modeling and rendering package. However, before you can make anything, you need to understand several concepts used in 3D modelling and related fields. Examples include:

- Understanding the process of 3D modeling and rendering

- Understanding how the axis and 3D coordinates work in Blender.

- Understanding orthographic and perspective views.

- Local coordinates, parent objects, and child objects.

- Blender's user interface and how to navigate it.

- Viewing a scene from different camera angles

Don't be scared by their long names; a lot of these are actually pretty intuitive and easy to grasp. Of course, since you're not doing any actual modelling in this unit, you might be tempted to skip ahead, and that's completely fine! Just know that understanding these concepts well will help you a lot in the long run, and proceeding through tutorials in order will build a strong foundation for you to build on. Prior knowledge also plays a huge part in this, so if you're coming from other 3D software, you should already be familiar with these concepts.

That said, the actual fun (making stuff in Blender) comes in the next unit. However, keep in mind that Blender is not the kind of software you can jump into and experiment with. It's notorious for having a steep learning curve. It's less like exploring an unfamiliar city and more like flying a spaceship; if you hop into the pilot's seat without knowing the fundamentals, it's going to be near impossible to get off the ground.

Blender-specific terminology

[edit | edit source]Like any subject, 3D graphics has its own words and terminology used to describe specific ideas. In this book, important words are highlighted and defined on their first use. If you've missed or forgotten the meaning of a word, try looking it up in the Glossary.

Things you'll need

[edit | edit source]In order to follow the tutorials, you need a computer with Blender installed. You can download the latest Blender release here.

Depending on your system, you may also need the appropriate Python installation. Each version of Blender requires a specific version of Python, but it's usually packaged with Blender.

The Blender team has the Blender Long Term Support program which provides a stable Blender version with 2 years of support. During the 2 year support window, no new features, UI changes, API changes or other enhancements will be done; only critical fixes will be applied. This allows teams working on long-lasting blender projects to use a single supported version over a 2 year period. Long term versions are indicated below with the LTS suffix and a year indicating the last year of support.

| Blender version | Python version |

|---|---|

| 2.79 | 3.5 |

| 2.83 LTS 2022 | 3.7 |

| 2.90 | 3.7 |

| 2.93 LTS 2023 | 3.9 |

| 3.0 | 3.9 |

| 3.1 | 3.10 |

| 3.3 LTS 2024 | 3.10 |

| 3.4 | 3.10 |

| 3.5 | 3.10 |

| 3.6 LTS 2025 | 3.10 |

| 4.0 | 3.10 |

| 4.1 | 3.11 |

You can check Python version on Scripting workspace using:

import sys

print(sys.version)

Since Blender is open-source software, you can download the source code and build it yourself, but it's easier to download a pre-built binary. As of Blender 4.0, compiled releases are provided for the following operating systems:

- Windows 8.1, 10, and 11

- macOS 11.2 Intel or Apple Silicon

- Linux with glibc 2.28 or newer

Along with the website, many Linux distributions have Blender available in their package repositories, though it may be a slightly older version. You can use your system's package manager to download and install the package. It's also available on steam.

Windows users can also choose between an executable installer ("setup wizard") and a ZIP archive.

After the installation process is finished, Blender should appear in the Graphics section of your desktop environment application menu.

You may also want to download a 2D image editor, such as GIMP, Paint.NET, or Photoshop or a media player, such as VLC.

It's a good idea to have pencil and paper handy for sketching and taking notes. There's a lot to absorb. Taking notes as you go will pay dividends later.

Where to Go for Help

[edit | edit source]If you get stuck, you can ask for help from other Blender users in the appendices.

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source]Many modules have a section like this at the bottom, listing websites with information on the topics covered in the module.

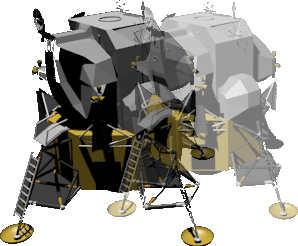

What Blender Can Do

[edit | edit source]In this module, you'll learn what Blender does, both in terms of the product (images) and the process (3D modeling).

Blender is a free software package for authoring "three-dimensional" (3D) graphics (also known as computer graphics or “CG”), including still images, games, and video.

While the end-product of most Blender projects is a two-dimensional (2D) raster image on a flat surface (be it a monitor, movie screen, or sheet of paper) except for Head Mounted Virtual Reality applications, the images are said to be "3D" because they exhibit the illusion of depth. In other words, someone looking at the image can easily tell which parts are meant to be closer and which are farther away.

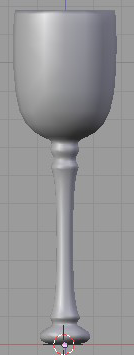

An Example

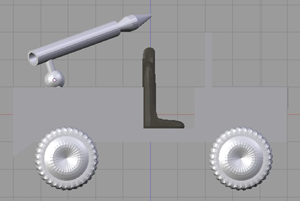

[edit | edit source]Here's a realistic still image that was created with Blender.

Look closely at the building.

- Because it is obscured by the building, you can tell that the tree-lined hillside is behind the building instead of vice versa.

- The way the top and bottom edges of the front wall appear to converge toward the base of the tree allow you to judge the angle between the front wall and your viewpoint.

- Your brain interprets dark portions of the wall as shadows, allowing you to estimate where the light is coming from, even though the sun is outside the frame of the image.

While an illusion of depth can be authored by hand with 2D graphics software (or a paintbrush!), Blender provides a much easier way.

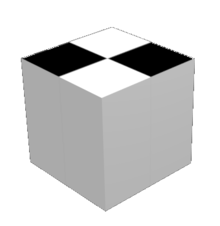

It's likely that the lonely house never existed outside of the artist's mind. Instead of building a big set on a rural lot in Germany, waiting for the right light, and photographing it, the author built a scene in a virtual 3D world—one contained inside a computer. This is called CGI (Computer Generated Imagery). They then used Blender to render the scene (convert it into a 2D image). You can view more of what Blender can do at the Blender gallery: http://www.blender.org/features/

Steps in the 3D Production Process

[edit | edit source]To produce an image like the one above involves two major steps to start with:

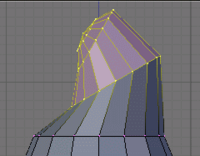

- Modelling, which is the creation of your miniature 3D world, also known as a model or scene. This involves defining the geometry of the objects, making it look like they are made out of particular materials, setting up the lighting, and defining a camera viewpoint.

- Rendering, which is the actual generation of the image of the world from the viewpoint of the camera (taking a “photograph” of the scene, if you like), for your audience to enjoy.

3D is often used to produce not just single still images, but animations as well. This requires some additional steps:

- Rigging — setting up a rig, namely a way of deforming (changing the shape of) a character in various repeatable ways to convincingly mimic joint movements, facial expressions and other such actions of real-life people or animals.

- Posing — choreographing the positions of the objects and their parts in the 3D scene over time, using the previously-created animation rigs

- Rendering now involves creating a whole sequence of frames representing movement over time, rather than just a single still frame.

But that’s not all. There are frequently additional processes to embellish the results of the above, to make them look more realistic:

- Sculpting — a more organic form of modelling objects by shaping them as though they were made out of clay. This produces more complicated, irregular shapes which mimic real objects found in nature, as opposed to clean, simple, geometrical ones which mostly only exist in the world of mathematics.

- Texture painting — You’re probably familiar with programs that let you paint an image on a 2D digital canvas. Such programs are commonly used in 3D production, to create textures which are “wrapped” around the surfaces of 3D objects to give them a more interesting appearance. 3D programs also often allow direct painting on the surfaces of those objects, so the effect of the design can be observed immediately, instead of having to go through a separate paint-on-a-flat-surface-then-wrap sequence of steps.

- Physical modelling — simulating the behaviour of real-world objects subject to real-world forces, for example hard balls colliding, soft cloth draping itself over an obstacle under gravity, water flowing and pouring. Mathematical formulas are available for these that give results very close to real life, all you need is the computing power to calculate them.

- Motion capture, or mocap: producing convincing animations, particularly ones that look like the movements of real people (walking, running, dancing etc) can be hard. Hence the technique of capturing the motions of live actors, by filming them with special markers attached to strategic points on their bodies, and doing computer processing to track the movements of these markers and convert them to corresponding movements of an animation rig.

- Compositing — this is where 3D renders are merged together with real photographic/live-action footage, to make it look like a rendered model is in the middle of a real-world scene, or conversely a real live actor is in the middle of a rendered scene. If done with proper skill, in particular due care to matching the effects of lights and shadows, the viewer becomes unable to tell what is real and what is not!

And just to add another complication to the mix, there are two kinds of rendering:

- Real-time rendering is rendering that has to happen under tight time constraints, typically for interactive applications like video gaming. For example, most gamers expect the screen to be updated 60 times per second in order to render smooth motion and respond quickly enough to player actions. These time constraints impose major limitations on the kinds of rendering techniques that can be used.

- Non-real-time rendering is where the time constraints are not so tight, and quality is the overriding factor. For example, when producing a single still frame, it may not matter so much that it takes minutes or hours to do so, because the beauty and detail of the final image is worth it. When rendering a Hollywood-quality movie, it may still take hours per frame, but the use of a render farm of hundreds or thousands of machines, all working on different frames at the same time, allows the entire sequence to complete in just a few weeks.

But wait, there’s more: There are also some areas, which might be considered to be stepping outside of traditional 3D production work, where Blender provides functionality:

- Video editing — having rendered your animation sequences and shot your live-action footage, you will want to combine them in a properly-timed linear sequence to tell a coherent story.

- 3D printing — Many people are interested in creating physical objects using 3D printers. The shape data may be obtained from real objects with 3D scanning, or it may be created from scratch using 3D modelling, or you can even combine both processes.

Blender is a capable tool for every single one of these processes. There’s quite a lot there, isn’t there? But don’t be too intimidated: this Wikibook will take things step by step, and you will be able to produce some fun stuff from early on.

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source] 3D rendering at Wikipedia.

3D rendering at Wikipedia. Render farm at Wikipedia.

Render farm at Wikipedia. Comparison of 3D computer graphics software at Wikipedia.

Comparison of 3D computer graphics software at Wikipedia. Computer-generated imagery at Wikipedia.

Computer-generated imagery at Wikipedia. Depth perception at Wikipedia.

Depth perception at Wikipedia.- Blender Art Gallery

- Blender Homepage

3D Geometry

[edit | edit source]

If you haven't previously studied 3D graphics, technical drawing, or analytic geometry, you are about to learn a new way of visualizing the world, an ability that's fundamental to working with Blender or any 3D modeling tool.

3D modeling is based on geometry, the branch of mathematics concerned with spatial relationships, specifically analytical geometry, which expresses these relationships in terms of algebraic formulas. If you have studied geometry, some of the terminology will be familiar.

Coordinates And Coordinate Systems

[edit | edit source]Look around the room you’re in. The odds are it will have a cuboidal shape, with four vertical walls at right angles to each other, a flat, horizontal floor, and a flat, horizontal ceiling.

Now imagine there’s a fly buzzing around the room. The fly is moving in three-dimensional space. In mathematical terms, that means its position within the room at any given moment, can be expressed in terms of a unique combination of three numbers.

There are an infinite number of ways —coordinate systems— in which we could come up with a convention for defining and measuring these numbers, i.e. the coordinates. Each convention will yield different values even if the fly is in the same position. Coordinates only make sense with reference to a specific coordinate system! To narrow down the possibilities (in a purely arbitrary fashion), let us label the walls of the room with the points of the compass: in a clockwise direction, North, East, South and West. (If you know which way really is north, feel free to use that to label the walls of your room. Otherwise, choose any wall you like as north.)

Consider the point at floor level in the south-west corner of the room. We will call this (arbitrary) point the origin of our coordinate system, and the three numbers at this point will be . The first of the three numbers will be the distance (in some suitable units, let’s say metres) eastwards from the west wall, the second number will be the distance north from the south wall, and the third number will be the height above the floor.

Each of these directions is called an axis (plural: axes), and they are conventionally labelled X, Y and Z, in that order. With a little bit of thought, you should be able to convince yourself that every point within the space of your room corresponds to exactly one set of values, and that every possible combination of values, with , and (where is the east-west dimension of your room, is its north-south dimension, and is the height between ceiling and floor) corresponds to a point in the room.

The following diagram illustrates how the coordinates are built up, using the same colour codes that Blender uses to label its axes: red for X, green for Y and blue for Z (an easy way to remember this if you're familiar with RGB is the order -- Red X, Green Y, Blue Z). In the second picture, the x value defines a plane parallel to the west wall of the room. In the third picture, the y value defines a plane parallel to the south wall, and in the fourth picture, the z value defines a plane parallel to the floor. Put the planes together in the fifth picture, and they intersect at a unique point.

Another simple way to understand what the coordinates of a point say (x,y,z) means is, if one starts from origin and moves x, y, and z units of distance parallel to x, y, and z axes respectively, in any sequence, one will reach that point. Thus, for example, a coordinate of (3,4,5) means the point which is reached when one moves, starting from origin, 3 units of distance along x-axis, 4 units of distance along y-axis and 5 units of distance along z-axis.

This style of coordinate system, with the numbers corresponding to distances along perpendicular axes, is called Cartesian coordinates, named after René Descartes, the 17th-century mathematician who first introduced the concept. Legend has it that he came up with the idea after watching a fly buzzing around his bedroom!

There are other ways to define coordinate systems, for example by substituting direction angles in place of one or two of the distance measurements. These can be useful in certain situations, but usually all coordinate systems in Blender are Cartesian. However, in Blender, switching between these coordinate systems is simple and easy to do.

Negative Coordinates

[edit | edit source]Can coordinate values be negative? Depending on the situation, yes. Here we are only considering points within our room. But suppose instead of placing our origin in the bottom southwest corner, we put it in the middle of the room, halfway between the floor and ceiling. (After all, it is an arbitrary point, we can place it wherever we like, as long as we agree on its location.) If the X-coordinate is the distance east from the origin, how do we define a point west of the origin? We simply give it a negative X-coordinate. Similarly, points north of the origin have a positive Y-coordinate, those south of it, have negative Y-coordinates. Points above the origin have a positive Z-coordinate, those below it, a negative Z-coordinate.

Handedness Of Coordinate Systems

[edit | edit source]It is conventional for most Cartesian coordinate systems to be right-handed. To understand this, hold the thumb, index finger and middle finger of your right hand perpendicular to each other:

Now orient your hand so your thumb points along the X-axis in the positive direction (direction of increasing coordinate numbers), your index finger along the positive Y-axis, and your middle finger along the positive Z-axis. Another way of looking at it is, if you placed your eye at the origin, and you could see the three arrows pointing in the directions of positive X, positive Y and positive Z as in Figure 1, the order X, Y, Z would go counter clockwise.

Another way to visualize this is to make a fist with your right hand, with your curled fingers towards you. Stick out your thumb directly to the right (X). Now aim your pointer finger straight up (Y). Finally, make your middle finger point toward yourself (Z). This is the view from directly above the origin.

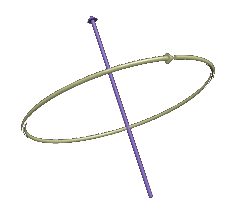

Axes Of Rotation

[edit | edit source]Consider a spinning sphere. Every point on it is moving, except the ones along the axis. These form a motionless line around which the rest of the sphere spins. This line is called the axis of rotation.

More precisely, the axis of rotation is a point or a line connecting points that do not change position while that object rotates, drawn when the observer assumes he/she does not change position relative to that object over time.

Conventionally, the direction of the axis of rotation is such that if you look in that direction, the rotation appears clockwise, as illustrated below, where the yellow arrow shows the rotational movement, while the purple one shows the rotation axis:

To remember this convention, hold your right hand in a thumbs-up gesture:

If the rotation follows the direction of your curled fingers, then the direction of the axis of rotation is considered to be the same as the direction which the thumb is pointing in.

This gesture is a different form of the right-hand rule and is sometimes called the right-hand grip rule, the corkscrew-rule or the right-hand thumb rule. From now on we will refer to it as 'the right-hand grip rule'.

When describing the direction of a rotating object, do not say that it rotates left-to-right/clockwise, or right-to-left/counterclockwise. Each of these on their own are meaningless, because they're relative to the observer. Instead of saying this, find the direction of the axis of rotation and draw an arrow to represent it. Those who know the right-hand grip rule will be able to figure out what the direction of rotation of the object is, by using the rule when interpreting your drawing.

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source]- the Geometry wikibook

Analytic geometry at Wikipedia.

Analytic geometry at Wikipedia. Cartesian coordinate system at Wikipedia.

Cartesian coordinate system at Wikipedia. Right-hand rule at Wikipedia.

Right-hand rule at Wikipedia. Rotation at Wikipedia.

Rotation at Wikipedia.

Coordinate Transformations

[edit | edit source]

Coordinate Transformations

[edit | edit source]A transformation is any operation that changes coordinate values in some way. For example, if you pick up an object and move it to a different place in the room without changing its orientation, then the coordinates of each point on the object relative to the room are adjusted by an amount that depends on the distance and direction between the old and new positions. This is called a translation transformation.

|

|

Simply turning the object without moving it from its original location is called rotation.

If the object were to get bigger or smaller, that is a scaling transformation. In the real world, only a few objects can be scaled in this way. For example, a balloon can be inflated or deflated to a larger or smaller size, but a bowling ball cannot. Regardless of what can and can't be re-sized in the real world, any object can be scaled (re-sized) in the world of computer graphics. Scaling may be uniform, i.e. apply equally in all dimensions, or non-uniform.

|

|

Linear Transformations

[edit | edit source]The main types of coordinate transformations we’re concerned with are called linear transformations. Lines that were straight before the transformation remain straight. i.e. they do not become curved. For example, the following diagram illustrates three linear transformations applied to the square in the center: Clockwise from the left, a shear or skew, a scale, and a rotation, plus one non-linear transformation that causes two sides of the box to become curved.

Multiple Transformations

[edit | edit source]It is possible to concatenate or compose a series of transformations. The resulting transformation can do many things in one operation — translation, rotation, scaling etc. However, the order of composition of the component transformations becomes important. In general, transformations are not commutative. For example, compare the result of moving our model some distance along the Y axis followed by rotating it about the X axis (If this doesn't make sense, consider that the axes are fixed, they aren't moving with the object. More on that later Global and local coordinates):

versus the result of doing the rotation first:

In some instances, the three forms of transformation may be applied on a single object concurrently. Such a feature exists in Blender and is normally implemented in creating animations. For example, you can decide to pick up the object (first transformation - translation), twist it (second transformation - rotation), and, in a 3D modeling environment, increase the size of the object (third transformation - scaling).

Inverse Transformations

[edit | edit source]Often there is a need to find the inverse of a transformation. That is, a transformation that has the opposite effect. For example, a rotation of +45° about the X axis is undone by a rotation of -45° around the same axis.

Inverses have many uses, one of which is to simplify the construction of certain kinds of transformations.

For example, it is easy to construct a rotation transformation about the X, Y or Z-axis of the coordinate system. But what about a rotation of Θ° around an arbitrary axis? This can be made out of the following parts:

- a translation that makes the rotation axis pass through the origin.

- rotations about the Y and/or Z axes, as appropriate, so the rotation axis lies along the X axis.

- a rotation of Θ° about the X axis.

- the inverse of the rotations that aligned the rotation axis with the X axis.

- the inverse of the translation that made the rotation axis pass through the origin.

Most of the transformations we deal with in 3D modelling have an inverse, but not all. See the next section for some that don’t.

Projections

[edit | edit source]Most of our display and output devices are not three-dimensional. Thus, three-dimensional images need to be projected onto a two-dimensional surface (like a display screen or a printed page) before we can see them.

There are two main ways to perform such projections. One is orthographic projection, where parallel lines are drawn from all points of the three-dimensional object until they intersect a plane representing the display surface:

The other method is perspective projection, where the lines drawn are not parallel, but intersect at a point representing the location of the eye of the viewer:

Projections are also linear transformations. But since they take a three-dimensional space and flatten it onto a two-dimensional surface, some information is lost. Those transformations are irreversible i.e. they cannot be undone, at least in a unique way as the depth information is gone.

You will read more about both orthographic and perspective views in the following pages.

The mathematics of perspective were first worked out in the 11th century by Alhazen, and used to great effect by the Italian Renaissance painters four hundred years later.

Orthographic Views

[edit | edit source]

Orthographic Views

[edit | edit source]An orthographic view (or projection) of a 3D scene is a 2D picture of it in which parallel lines appear parallel, and all edges perpendicular to the view direction appear in proportion, at exactly the same scale.

Orthographic views are usually aligned with the scene's primary axes. Edges parallel to the view axis disappear. Those parallel to the other primary axes appear horizontal or vertical. The commonly used orthographic views are front, side, and top views, though back and bottom views are possible.

Uniform scale makes an orthographic view very useful when constructing 3D objects, not only in computer graphics, but also in manufacturing and architecture.

Here's one way to think about the orthographic view:

Imagine photographing a small 3D object through a telescope from a very great distance. There would be no foreshortening. All features would be at the same scale, regardless of whether they were on the near side of the object or its far side. Given two (or preferably three) such views, along different axes, you could get an accurate idea of the shape of the object, useful for "getting the feel" of objects in a virtual 3D world where you're unable to touch or handle anything!

Example

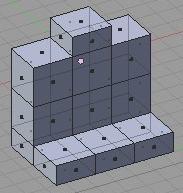

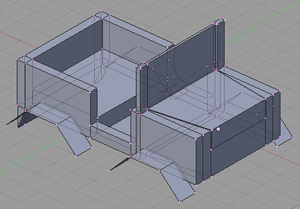

[edit | edit source]Here is a drawing of a staircase:

and here are three orthographic views of the same staircase, each outlined in red:

The views are from the front, top, and left. Dashed lines represent edges that, in real life, would be hidden behind something, such as the left wall of the staircase. (Think of each view as an X-ray image.)

The leading edges of the steps are visible in both the front and top views. Note that they appear parallel and of equal length in 2D, just as they are in 3D reality.

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source] Orthographic projection at Wikipedia.

Orthographic projection at Wikipedia.

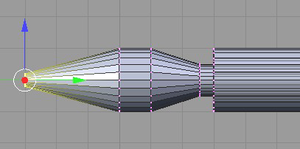

Perspective Views

[edit | edit source]As you know, the main reason for modeling 3D objects in Blender is to render images that exhibit the illusion of depth.

Orthographic views are great for building a house, but seriously flawed when it comes to creating realistic images of the house for use in a sales brochure. While a builder wants blueprints that are clear and accurate, a seller wants imagery that's aesthetically pleasing, with the illusion of depth. Blender makes it easy to use tricks like perspective, surface hiding, shading, and animation to achieve this illusion.

How does perspective work?

The essence of perspective is to represent parallel edges (in a 3D scene) by edges (in the 2D image) that are not parallel. When done correctly, this produces foreshortening (nearby objects are depicted larger than distant ones) and contributes to the illusion of depth.

Perspective is challenging to draw by hand, but Blender does it for you, provided you give it a 3D model of the scene and tell it where to view the scene from.

|

Blender only supports 3-point perspective, not 1-point or 2-point. |

If you're confident you understand perspective, you can skip the rest of this module and proceed to the "Coordinate Spaces in Blender" module.

One-point Perspective

[edit | edit source]

Drawing classes teach various kinds of perspective drawing: one-point perspective, two-point perspective, and three-point perspective. In this context, the word "point" refers to what artists call the vanishing point.

When you're looking at a 3D object head-on and it's centered in your view, that is an example of one-point perspective.

Imagine looking down a straight and level set of train tracks. The tracks appear to converge at a point on the horizon. This is the vanishing point.

The image on the right is a 2D image of a cubic lattice or framework. Like any cube, it has six square faces and twelve straight edges. In the 3D world, four of the edges are parallel to our line-of-sight. They connect the four corners of the nearest square to the corresponding corners of the farthest one. Each of these edges is parallel to the other three.

In the 2D image, those same four edges appear to converge toward a vanishing point, contributing to the illusion of depth. Since this is one-point perspective, there is a single point of convergence at the center of the image.

Two-point Perspective

[edit | edit source]

Now the cube is at eye level, and you're near one of its edges. Since you're not viewing it face-on, you can't draw it realistically using one-point perspective. The horizontal edges on your left appear to converge at a point on the horizon to the left of the cube, while those on the right converge to the right. To illustrate the cube with a good illusion of depth, you need two vanishing points.

Three-point Perspective

[edit | edit source]

Now imagine you're above the cube near one of its corners. To draw it, you'd need three vanishing points, one for each set of parallel edges.

From that perspective, there are no longer any edges which appear parallel. The four vertical edges, the four left-right edges, and the four in-out edges each converge toward a different vanishing point.

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source] Perspective (graphical) at Wikipedia.

Perspective (graphical) at Wikipedia.

Coordinate Spaces in Blender

[edit | edit source]

We'll start looking at how 3D scenes are represented in Blender.

As was explained in the "3D Geometry" module, Blender represents locations in a scene by their coordinates. The coordinates of a location consist of three numbers that define its distance and direction from a fixed origin. More precisely:

- The first (or x-) coordinate of the location is defined as its distance from the YZ plane (the one containing both the Y and Z axes). Locations on the +X side of this plane are assigned positive x-coordinates, and those on the -X side are given negative ones.

- Its second (or y-) coordinate is its distance from the XZ plane, with locations on the -Y side of this plane having negative y-coordinates.

- Its third (or z-) coordinate is its distance from the XY plane, with locations on the -Z side of this plane having negative z-coordinates.

Thus the origin (which lies at the junction of all three axes and all three planes) has the coordinates (0, 0, 0).

Global and local coordinates

[edit | edit source]Blender refers to the coordinate system described above as the global coordinate system, though it's not truly global as each scene has its own global coordinate system. Each global coordinate system has a fixed origin and a fixed orientation, but we can view it from different angles by moving a virtual camera through the scene and/or rotating the camera.

Global coordinates are adequate for scenes containing a single fixed object and scenes in which each object is merely a single point in the scene. When dealing with objects that move around (or multiple objects with sizes and shapes), it's helpful to define a local coordinate system for each object, i.e. a coordinate system that can move with, and follow the object. The origin of an object's local coordinate system is often called the center of the object although it needn't coincide with the geometrical center of the object.

3D objects in Blender are largely described using vertices (points in the object, singular form: vertex). The global coordinates of a vertex depend on:

- the (x, y, z) coordinates of the vertex in the object's local coordinate system

- the location of the object's center

- any rotation (turning) of the local coordinates system relative to the global coordinate system, and

- any scaling (magnification or reduction) of the local coordinate system relative to the global coordinate system.

For example, the teacup in Figure 1 is described by a mesh model containing 171 vertices, each having a different set of local (x, y, z) coordinates relative to the cup's center. If you translate the cup (move it without rotating it), the only bits of the model that have to change are the global coordinates of the center. The local coordinates of all its vertices would remain the same.

Coordinates of child objects

[edit | edit source]

Any object can act as a parent for one or more other objects in the same scene, which are then referred to as its children. (An object cannot have more than one direct parent, but parent objects may themselves be the children of other objects.)

If an object has a parent, its position, rotation, and scaling are measured in the parent's local coordinate system, almost as if it were a vertex of the parent. i.e. the position of the child's center is measured from the parent's center instead of the origin of the global coordinate system. So if you move a parent object, its children move too, even though the children's coordinates have not changed. The orientation and scaling of a child's local coordinate system are likewise measured relative to those of its parent. If you rotate the parent, the child will rotate (and perhaps revolve) around the same axis.

Parent-child relationships between objects make it simpler to perform (and animate) rotations, scaling and moving in arbitrary directions. In Fig. 1b the teacup is a child object of the coordinate cross on the right. That cross is itself the child of an invisible parent. (It is both a parent and child.) In the cup's local coordinate system, it is not rotating, but as the cross on the right rotates around its Z axis, it causes the cup to rotate and revolve. In real animations, it will be much easier when the character holding the cup rotates, the cup changes its position respectively.

View coordinates

[edit | edit source]

Taking the viewer of the scene into consideration, there is another coordinate space: the view coordinates. In Fig. 2 the viewer is symbolized by the camera. The Z axis of the view coordinates always points directly to the viewer in orthographic projection. The X axis points to the right, the Y axis points upwards (Fig. 3).

In fact you always work in view coordinates if you don't set it any other way*. This is particularly useful if you have aligned your view prior to modeling something, e.g. if an object has a slanted roof and you want to create a window to fit in that roof, it would be very complicated to build the window aligned to the local coordinate system of the object, but if you first align your view to the slanted roof, you can easily work in that view coordinate system.

(* In the Blender 2.6 series, the default has been changed to global coordinates. View coordinates remain as an option.)

If you work in one of the three standard views (Front/Top/Side) the alignment of the view coordinates fits the global coordinates. Therefore, it is quite natural to model in one of the standard views and many people find this the best way to model.

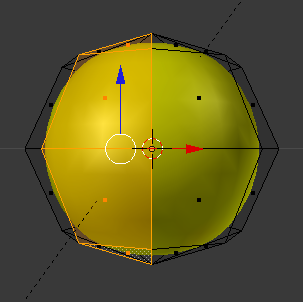

Normal coordinates

[edit | edit source]

Although Blender is a 3D program, only objects' faces are visible. The orientation of the faces is important for many reasons. For example, in our daily lives it seems quite obvious that a book lies flat on a table. This requires the surface of the table and that of the book to be parallel to each other. If we put a book on a table in a 3D program, there is no mechanism that forces these surfaces to be parallel. The artist needs to ensure that.

The orientation of a face can be described with the help of the so-called surface normal. It is always perpendicular to the surface. If several faces are selected, the resulting normal is averaged from the normals of every single face. In Fig. 4 the normal coordinates of the visible faces are drawn.

This concept can be applied to individual points on the object, even if the points themselves have no orientation. The normal of a point is the average of normals of the adjacent faces.

UV Coordinates

[edit | edit source]In later parts (for example, talking about textures) you will come across coordinates labelled “U” and “V”. These are simply different letters chosen to avoid confusion over “X”, “Y” and “Z”. For example, a raster image is normally laid out on a flat, two-dimensional plane. Each point on the image can be identified by X and Y coordinates. But Blender can take this image and wrap it around the surface of a 3D object as a texture. Points on/in the object have X, Y and Z coordinates. So to avoid confusion, the points on the image are identified using U and V to label their coordinates instead of X and Y. We then refer to “UV mapping” as the process of determining where each (U, V) image point ends up on the (X, Y, Z) object.

Overview

[edit | edit source]Blender's user interface (the means by which you control the software) is not particularly easy to learn. However, it has improved over time and is expected to continue doing so. The current version of the Blender software is available for download from the Blender Foundation's website.

The tutorials in this section will familiarize you with the basics of the user interface. By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- resize, split, and merge any Blender window;

- change the type of any Blender window;

- access user preferences;

- access panels containing buttons and other controls;

- change the viewpoint of a viewport.

For those new to Blender, this is a fundamental section of the book.

Advice on Customization

[edit | edit source]Blender is a complex software package with many customizable features. You can customize the user interface to assign new functions to buttons and hotkeys. In fact, you can change almost anything to suit yourself. However, this complicates the giving and following of directions. It is recommended you adhere to the default screen arrangements of Blender in order to be able to follow the remaining parts of these tutorials. Blender ships with 4 to 5 screen-content arrangements which are suitable for almost any kind of job you'll want to use it for - from creating motion and animation to making games.

We recommend leaving Blender's user interface in its "factory settings" while working through the Noob to Pro tutorials. At the very least, wait until you've mastered the basics before you customize the interface — and we know you definitely will when you master it!

Keystroke, Button, and Menu Notation

[edit | edit source]As you read through these tutorials, you will encounter cryptic codes such as SHIFT + LMB and Timeline → End Frame. They describe actions you perform using the keyboard and mouse. The notation used in this book comes from the standard used by the Blender community. We will try to import those standards here to facilitate our studies.

If you're reading this book online, you may wish to print this page for future reference. In addition, or as an alternative, you can bookmark it in your browser for faster reference.

Hotkeys

[edit | edit source]

Most computer keyboards have number keys in two different places. A row above the letters, and in a numpad (numeric keypad) to the right of the keyboard. While many applications use these two sets of keys interchangeably, Blender does not. It assigns different functions to each set. If you're using a laptop keyboard without a separate numeric keypad, this might cause some difficulty. You'll need to use your function key to do some things. It is possible to indicate to Blender the type of keyboard you are using, but we strongly recommend you use a standard external keyboard if you use a laptop for these tutorials as it will make your studies and usage of Blender much more straightforward and enjoyable.

This book often assumes your keyboard has a numpad. If yours doesn't, consult the tutorial on Non-standard Input Devices for alternative ways to access the numpad's functions.

Key Notation

[edit | edit source]| Notation | Corresponding key or action |

|---|---|

| Alt | The Alt key (known as ⌥ Option on Apple keyboards) |

| Cmd | The ⌘ Command key also known on other platforms as the ⌘ Windows key or ❖ Super key |

| Ctrl | The ⌃ Ctrl key (also known as the Control key) |

| Fn | The Fn key (also known as the Function key, generally found only on laptops) |

| Shift | The ⇪ Shift key |

| Enter | The ↵ Return key (also known as the Enter key) |

| Esc | The Esc key (also known as the Escape key) |

| F1 through F12 | The function keys F1 through F12 (often in a row along the top of the keyboard) |

| Space | The Spacebar |

| Tab | The ↹ Tab key |

| A through Z | The letters A to Z (on the keyboard) |

| 0key through 9Key | The digits 0 to 9, placed above the letters on the keyboard |

| Num0 through Num9 | The digits 0 to 9, placed on the numpad |

| NumLock , Num/ , Num* , NUM− , Num+ , NumEnter , and Num. | The NumLock, /, *, -, +, Enter, and . keys respectively, all located on the numpad. |

| Delete | The Delete key |

| Down Arrow | The ⇣ Down Arrow key |

| Left Arrow | The ⇠ Left Arrow key |

| Right Arrow | The ⇢ Right Arrow key |

| Up Arrow | The ⇡ Up Arrow key |

When a key is used in a module, it means press that key. For exammple:

- M means "press the M key"

- Num0 means "press the 0 key thats found on the numpad."

Combinations that involve holding down a key while performing another action are written with a plus sign (+). For example:

- Shift + Tab means "press Tab while holding down Shift "

- Shift + Ctrl + F9 means "press F9 while holding down both Ctrl and Shift "

Mouse Notation

[edit | edit source]Blender uses three mouse buttons and the scroll wheel, if you have one. If your mouse only has one or two buttons, consult the tutorial on Non-standard Input Devices for alternative ways to access the functions assigned to these buttons.

| Notation | Corresponding action |

|---|---|

| LMB | click with the Left Mouse Button |

| RMB | click with the Right Mouse Button |

| MMB | press down on (don't turn) the scroll wheel or Middle Mouse Button |

| SCROLL | turn the scroll wheel in either direction |

Mouse and keyboard actions are often combined. Shift + RMB means to click RMB while holding down Shift .

Navigating Menus

[edit | edit source]Blender uses both pop-up and pull-down/pull-up menus. Many menus have sub menus (menus that are reached via another menu). If a menu item displays a triangle, that means it leads to a sub menu.

You can move through items in a menu by either:

- Moving the mouse pointer up and down

- Pressing Up Arrow and Down Arrow

You can enter a sub menu by either:

- Moving the mouse pointer to the right

- Pressing Right Arrow while hovering over a menu item that shows a triangle on its side.

You can leave a sub menu by doing one of the following:

- moving the mouse pointer to the left

- pressing Left Arrow

To initiate a menu action, you can:

- click LMB

- press Enter

You can escape from a menu by:

- moving the mouse pointer away from the menu

- pressing Esc

For each menu, Blender remembers your last choice and highlights it for you the next time you enter the menu.

Notation

[edit | edit source]Menu notation is fairly self-explanatory.

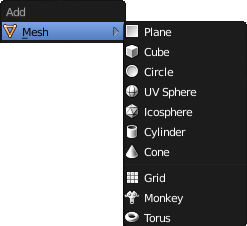

Shift + A Mesh → UV Sphere

Means:

- Press Shift+A

- In the menu that pops up, move through the items until Mesh is highlighted

- Enter the Mesh sub menu

- Move through the items until UV Sphere is highlighted

- Press Enter or click the left mouse button to initiate the action

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source]- the Blender Manual page on "keyboard and mouse" at http://wiki.blender.org/index.php/Doc:Manual/Interface/Keyboard_and_Mouse

Non-standard Input Devices

[edit | edit source]This module is applicable only to users with non-standard input devices. If you have both a three-button mouse and a keyboard with a numpad, you can skip this module.

Keyboards lacking a numpad

[edit | edit source]Most modern laptops have a pseudo-numpad, a set of keys in the main keypad which double as a numpad. The keys typically used for this purpose are:

| 7key | 8key | 9key | 0key |

| U | I | O | P |

| J | K | L | ; |

| M | ,Key | .Key | SLASH |

When used as a pseudo-numpad, these keys typically act as the following keys from a true numpad:

| Num7 | Num8 | Num9 | Num/ |

| Num4 | Num5 | Num6 | Num* |

| Num1 | Num2 | Num3 | NUM− |

| Num0 | NumENTER | Num. | Num+ |

The numpad functions of these keys can often be toggled with F11 or NUMLOCK on PCs or with F6 on Macs. Alternatively, you can often temporarily activate the numpad behavior by holding down Fn .

If your keyboard has the alternate labellings but you don't know how they work, consult your laptop owner's manual.

As a last resort, you can use the "Emulate Numpad" feature of Blender. This will allow you to use the normal numeric keys as if they were numpad numerics. Instructions for enabling this feature may be found in the "User Preferences Windows" module.

Blender uses the numeric keypad quite a bit. If you envision using your laptop for this kind of work, it may be worth investing in a USB Numeric Keypad. On eBay, prices for simple external numpads start around $10 USD.

Non three-button mouse

[edit | edit source]For single-button mouse users, make sure that Input for Blender 2.79 (under "User Preferences" on the left-most drop-down menu) → Emulate 3 Button Mouse is enabled.

On many computers with two-button mice, MMB can be emulated by simultaneously clicking LMB and RMB . On Windows machines you'll need to enable this in the mouse settings in the Control Panel. On a Mac, open the Keyboard and Mouse preference pane and enable Use two fingers to scroll. Alternatively, by selecting Emulate 3 Button Mouse under User Preferences, MMB can be emulated by simultaneously clicking Alt and LMB .

Recent IBM Thinkpad laptops allow you to disable the 'UltraNav' features of the middle mouse button in order to use it as a 'normal' third button. Alternatively, some laptops allow areas (called gestures) on the movement pad to act as MMB or RMB , and these can be set up in the Control Panel in the Mouse Pointer options, selecting gestures and editing features there.

Apple single-button mouse

[edit | edit source]| Notation | Single-button Substitute | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LMB | MB | the Mouse Button |

| RMB | Cmd + MB | Apple key + the Mouse Button |

| MMB | Alt + MB | Option (Alt) key + the Mouse Button |

While Mac OS X natively uses both the Ctrl + MB and Cmd + MB to emulate RMB , recent Blender releases for Mac OS X use only Cmd + MB for this purpose. This behavior is documented in the OSX Tips file that comes with the Mac version. You can also set the mouse to sense a right-click in System Preferences.

Note also that in the new, "unibody" design, the mouse button is under the trackpad, and the shortcut for RMB is clicking with two fingers simultaneously, which can be enabled in the System Preferences.

Laptops lacking a middle button but with a touchpad

[edit | edit source]Many laptops have touchpads. Touchpads, also known as trackpads or in some cases as smart-pads, can use gestures to give the effect of MMB . The default for an Elan® Smart-Pad is two-finger tapping equivalent to clicking a MMB . Dragging two fingers is the same as turning a mouse wheel.

Tablet PCs

[edit | edit source]To get the effect of MMB in a viewport, drag your pen around while holding down the Alt key.

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source]Operating System-specific Issues

[edit | edit source]This tutorial covers user-interface issues that are specific to particular operating systems or window managers. Read the section that applies to your computer; you may skip the rest.

GNU/Linux

[edit | edit source]Alt + LMB is used for changing the angular view on two angular axes of the 3D View window, if Alt + LMB moves the current window, then there's a conflict with your window manager. You can resolve the conflict or use Ctrl + Alt + LMB or MMB instead. (Also, you may have activated Compiz->Rotate Cube. Default configuration for rotating the Cube is also Ctrl + Alt + LMB ; you may have to change this binding to an alternative configuration.) If you are running KDE this can be resolved by: RMB on the title bar of the main Blender window → select Configure Window Behavior → go to Actions → Window Actions → in the Inner Window, Titlebar and Frame section → select the Modifier key to be Alt and set all the select boxes beneath it to Nothing. An alternate method within KDE might be to RMB click on the title bar of the main Blender window; then select Advanced → Special Application Settings... → Workarounds and then click Block global shortcuts with Force selected and checked.

In Gnome, Click System → Preferences → Window Preferences. Look for the last three options Control, Alt and Super. Select Super. Or in Xfce, click Whisker → Settings → Window Manager Tweaks, and in the Accessibility pane, change Key used to grab and move windows to Super. Now you can press and hold Cmd or ⊞ to drag windows around, and use Ctrl and Alt as normal.

KDE

[edit | edit source]Under KDE, Ctrl + F1 through Ctrl + F4 are by default configured to switch to the corresponding one of the first four desktops, while CTRL + F12 brings up Plasma settings. You can change these in System Settings.

Alternatively you can suppress global shortcuts while inside blender by adjusting the kwin rules for this application, which you can access with a RMB click on the title bar of the window and pressing more actions->add program rule.

Gnome

[edit | edit source]You'll want to disable the Find Pointer functionality in Gnome, which will impair your ability to use certain functions such as Snap to grid and the lasso tool. If your mouse pointer is being highlighted when you press and release Ctrl , go to: Mouse in Gnome's Desktop Settings and uncheck the box Find Pointer.

Ubuntu

[edit | edit source]As of Ubuntu versions prior to about 09.10 (“Karmic Koala”), there was a known incompatibility between Blender and the Compiz Fusion accelerated (OpenGL) window manager used in Ubuntu. By default, Compiz Fusion is enabled in Ubuntu, causing the problems to manifest themselves in Blender as flickering windows, completely disappearing windows, inconsistent window refreshes, and/or an inability to start Blender in windowed mode.

The fix for this is simple. Install compiz-switch (might be in universe). Go to Applications → Accessories → Compiz-Switch. This will disable compiz temporarily. Do the same to turn compiz back on when you're done using Blender.

This is no longer needed for current releases of Ubuntu.

Mac OS X

[edit | edit source]You may need to press Fn in order to use the F1 through F12 keys.

To expand a section in Blender, you would usually press Ctrl + UpArrow . On a Mac, if “Spaces” is enabled, you may have to use Ctrl + Alt + UpArrow .

Microsoft Windows

[edit | edit source]Two Ways to Launch Blender

[edit | edit source]Blender requires a console for displaying error messages, so if you launch Blender by means of an icon, two windows will appear: the graphical user interface plus a console window. Closing either window will terminate Blender. These windows are indistinguishable in the Windows taskbar in versions of Windows before Windows 7, which leads to confusion. Also, launching this way does not provide any way to pass command-line arguments to Blender.

Launching Blender from a command prompt is extra work, but it overcomes these issues:

- Start → Run...

- enter cmd

- enter cd c:\Program Files\Blender Foundation\Blender

- enter blender

Blender version 2.6 onwards doesn't have this problem, and hides the console window by default. You can show it by clicking Window > Toggle system console

Sticky Keys

[edit | edit source]Pressing Shift five times in a row may activate StickyKeys, an accessibility option which alters how the computer recognizes commands. If a StickyKeys dialog box appears, you should LMB the "Cancel" button.

If you don't need the accessibility features, you can disable sticky keys:

- Start → Control Panel (OR search for "Accessibility Options" on the Start menu/Search)

- double-click on Accessibility Options (Ease of Access Center in Windows 10)

- LMB the Keyboard tab

- for each of the options StickyKeys, FilterKeys, and ToggleKeys:

- clear the Use … checkbox

- LMB the Settings button

- uncheck the Use Shortcut checkbox in the settings

- LMB the OK button for the settings

- LMB the OK button for Accessibility Options/Ease of Access Center.

Multiple Keyboard Layouts

[edit | edit source]On systems with multiple keyboard layouts, pressing Shift + Alt can alter the layout. (For instance, it might change from QWERTY to AZERTY or vice versa.) Because of this issue, Noob to Pro avoids Shift + Alt hotkeys.

If you find your keyboard layout altered, press Shift + Alt again to change it back.

You can also disable the hotkey:

- Start → Control Panel

- double-click on Regional and Language Options

- LMB the Languages tab

- LMB the Details button

- LMB the Key Settings button

- LMB the Change Key Sequence button

- uncheck the Switch Keyboard Layout checkbox

- LMB the OK button

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source]- Input method editor keyboard shortcut (CTRL+SHIFT+0) switches the input language in Vista — Microsoft Support Knowledge-Base

StickyKeys at Wikipedia.

StickyKeys at Wikipedia.

Blender User Interface

[edit | edit source]

|

|

Applicable Blender version: 2.90. |

Here's a preview screenshot of Blender's interface, after a new installation.

For those familiar with older versions of Blender, this will look very different. The redesign makes it much easier to find things.

For a detailed rationale explaining the redesign, read this.

Why does Blender use its own windowing system instead of the operating system's?

[edit | edit source]Blender follows its own user interface conventions. Instead of making use of multiple windows as defined by your particular OS/GUI, it creates its own “windows” within a single OS/GUI window, which is best sized to fill your screen. Many people accustomed to how applications normally work on their platform of choice, get annoyed by Blender’s insistence on being different. However, there is a good reason for it.

The essence of the Blender UI can be summed up in one word: workflow. Blender was originally created by a 3D graphics shop for their own in-house use. Being a key revenue engine for them, they designed it for maximum productivity, speed and smoothness of operation. That means avoiding “bumps” that slow down the user. For example, windows never overlap, so there’s no need to keep reordering them. You don’t have to click in a window to make it active, just move the mouse. There is a minimum of interruption from popups asking for more information before performing some action. Instead, the action is immediately performed with default settings, which you can adjust afterwards and get immediate feedback on the results.

Blender may not be “intuitive” to start learning, in that you cannot simply sit down in front of it and figure out things on your own, especially from a position of knowing nothing at all. But once you have picked up some basic conventions, you will find it starts to make sense and then you will be free to experiment and discover things on your own.

"Save changes on exit" prompt

[edit | edit source]As of Blender version 2.79, you are prompted on exit when there are unsaved changes. You can change this behaviour in Edit → Preferences → Save & Load → Save Prompt.

Prior to that version, Blender was not asking about unsaved changes. Instead, Blender saved changes, when it closes, to a file called 'quit.blend'. The next time you use Blender, you had to select File → Recover Last Session to resume right where you left off.

Blender Windowing System

[edit | edit source]|

|

Applicable Blender version: 2.69. |

The Blender user interface may appear daunting at first, but don't despair. This book explores the interface one step at a time.

In this module, you'll learn about Blender windows:

- recognizing windows and their headers,

- the different types of windows,

- how to activate and resize windows,

- how to split and join windows.

You'll also practice launching and leaving Blender.

An Interface Divided

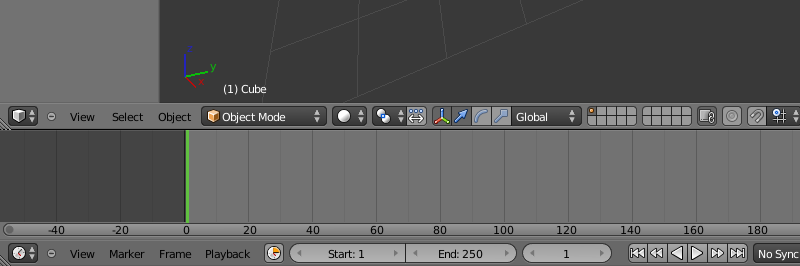

[edit | edit source]Blender's user interface is divided into rectangular areas called windows (or sometimes, areas). The overall arrangement of windows is called a workspace.

If you haven't already launched Blender, go ahead and do so. You should soon see something that resembles the following.

Blender has had some major changes to its user interface (UI) since version 2.4x. Some of these changes include moving buttons and changing the space bar hot key from the “add menu” to the “search menu” ( SHIFT + A is now the "add menu” hot key). This is important to know when trying to follow tutorials.

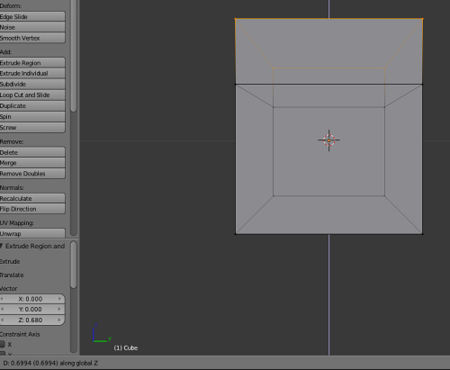

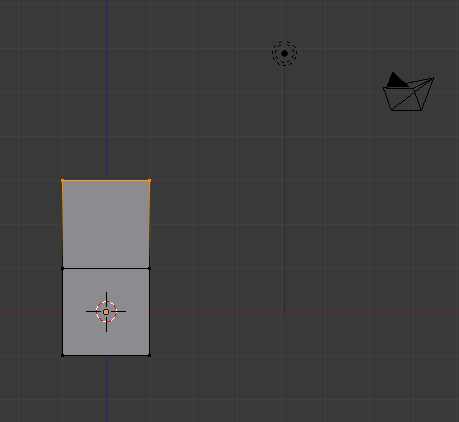

Other changes include the addition of the tool bar and window splitting widget. The shelf widget (indicated by a plus sign) opens hidden tool shelves. The object tool shelf can be toggled on and off by pressing T . The properties tool shelf can be toggled on and off by pressing the N . The split window widget allows you to split and join windows. Blender 2.69 is shown below.

- You may be running a different version of Blender - perhaps a newer version. The screenshot was made using the 2.69 release.

- If you're running an older version, you should probably upgrade. Download instructions are in the Introduction.

- The user-interface settings on your computer may have been changed.

- Try resetting the user interface with File → Load Factory Settings.

- To take a video in Blender, press Alt + F3 , and click Make Screencast. This will record what's on your screen until you click the red Close button on the info header. The screencasts will be saved in the tmp folder. In Microsoft Windows, the tmp folder is located at 'C:\tmp'.

Window Headers

[edit | edit source]Did you find all five headers?

Every Blender window has a header. A header can appear at the top of the window, at the bottom of the window, or it can be hidden. Let's take a closer look at the headers.

The header of the 3D View window is outlined in red. Note that it runs along the bottom of the 3D View window, not the top.

The header of the Properties window is outlined in blue.

The header of the Outliner window is outlined in white.

The header of the Timeline window is the one on the bottom (not outlined)

If you click with RMB on the header, a menu pops up which lets you move the header (to the top if it’s at the bottom, or vice versa), or maximize the window to fill the entire workspace:

To hide the header completely, move the mouse to the edge of the header furthest from the edge of the window (i.e. the top edge of the header if it is at the bottom of the window, or vice versa); it will change into a vertical double-headed arrow. Now click with LMB and drag towards the window edge, and the header will disappear. In its place, you will see the following symbol appear at the corner of the window: ![]() . Click this with LMB to bring the header back.

. Click this with LMB to bring the header back.

Window Types

[edit | edit source]Blender has many types of windows (there are 16 of them in Blender 2.69) and a Console for the Python programming language. You've just encountered the Info, 3D View, Properties, and Outliner windows. The rest will be introduced as needed in later modules.

Every window header in Blender has an icon at the left end to indicate the window type. For instance:

If you LMB on the icon, a menu will pop up. (If you don't know what LMB means, please review the Keystrokes, Buttons, and Menus Notation module.)

The menu can be used to alter a window's type. In this screenshot, the user is about to change the window into a Properties window.

|

Any window can be changed to any type. Blender doesn't mind if there are multiple windows of the same type. |

|

The workspace layout is saved along with the document. Anybody subsequently opening the document will see the last-saved layout. |

If you've changed any window's type, please change it back (or reload the factory settings with File → Defaults → Load Factory Settings) before continuing with this tutorial.

The Active Window

[edit | edit source]The active window is the one that will respond if you press a key. Only one Blender window is active at any given time.

The active window is usually the one containing the mouse pointer. (Blender uses a "focus follows mouse" user interface model. When a hotkey fails to work as expected, it is often because the mouse pointer has strayed into a neighboring window.) To change the active window, simply move the mouse pointer into the window you wish to activate.

Practice changing the active window by moving your mouse between the 3D View and the Timeline windows. The Timeline window is directly below the 3D View header. At this point, it's worth mentioning that the header for the 3D View window and Timeline window is at the BOTTOM of its own window instead of the top as the name "header" implies.

|

When a window becomes active, its header gets brighter. |

Resizing Windows

[edit | edit source]Resizing windows is easy.

Dragging on a Border

[edit | edit source]

Drag with the mouse to move the border up and down.

When the border is where you want it, release LMB .

Whenever you increase the size of one window, you decrease the size of another. That's because Blender has a non-overlapping window interface: unlike many other programs, it does not permit windows to overlap. Neither does it move windows; it just resizes them. If you find that you cannot increase the size of a window (e.g. the Info window) any further although there seems to be enough space to do so, it may be because you decreased the size of another window (e.g., the Outline window) to its minimum size (i.e, just the heading).

Maximizing a Window

[edit | edit source]Another way to resize a window is to maximize it. When Blender maximizes a window, it makes the window as large as possible. The previous window configuration is saved.

- To maximize the active window, press Ctrl + UpArrow , Ctrl + DownArrow or Shift + Space . On a Mac, if “Spaces” is enabled, you may have to use Ctrl + Alt + UpArrow .

- When a window is maximized, use Ctrl + UpArrow , Ctrl + DownArrow or Shift + Space to restore the previous (unmaximized) window configuration.

Practice maximizing and un-maximizing the 3D View and Timeline windows.

|

If you are running a version of Blender before 2.57, you cannot maximize a User Preferences window. |

Shelves

[edit | edit source]You will notice that the 3D View ![]() window (the largest window in the screenshots above) has several buttons down the left side. This rectangular portion is called the Tool Shelf. This is like a window within a window - you can drag the boundary between it and the main part of the 3D View to resize.

window (the largest window in the screenshots above) has several buttons down the left side. This rectangular portion is called the Tool Shelf. This is like a window within a window - you can drag the boundary between it and the main part of the 3D View to resize.

If you drag all the way to the window boundary, the shelf will disappear. In its place, the following symbol will appear: ![]() . Click it to bring the shelf back.

. Click it to bring the shelf back.

Too Much To Fit

[edit | edit source]If a window or shelf contains too much information to fit within its display area, scrollbars will appear along the bottom or right edge. You can scroll the contents by dragging these with LMB ; alternatively you can drag with MMB directly within the contents.

A window header may also contain more than fits within its displayable area. There is no explicit visual clue for this (though some of the widgets at the right edge might not be visible), but if that happens, you can drag sideways within the header with MMB to scroll its contents.

Splitting And Joining Windows

[edit | edit source]At the top right and bottom left of every window, you will see something like this: ![]() . If you move the mouse over the icon, you will see the pointer turn into a cross. At that point, you can do one of the following by clicking and dragging with LMB :

. If you move the mouse over the icon, you will see the pointer turn into a cross. At that point, you can do one of the following by clicking and dragging with LMB :

- Split the window into two copies horizontally by dragging horizontally away from the edge.

- Split the window into two copies vertically by dragging vertically away from the edge.

- Join the window to the adjacent one horizontally (getting rid of it and taking over its space) by dragging towards it.

- Join the window to the adjacent one vertically (getting rid of it and taking over its space) by dragging towards it.

Of course, the last two are only possible if there is in fact another window in that direction. Note: you can only join windows horizontally that are the same height, and windows vertically that are the same width.

The Default Workspace

[edit | edit source]If you look at the above screenshot of the default workspace, you will see the following window types:

- The menu bar at the top (outlined in green) is actually a window, called Info

. In previous versions of Blender, you could resize this to reveal the User Preferences, but in 2.5x they have been moved to their own window type. Instead, all you can see here if you enlarge the window are some debug messages, which may be removed in a future version of Blender. As of 2.70, the debug messages are still present in this menu.

. In previous versions of Blender, you could resize this to reveal the User Preferences, but in 2.5x they have been moved to their own window type. Instead, all you can see here if you enlarge the window are some debug messages, which may be removed in a future version of Blender. As of 2.70, the debug messages are still present in this menu. - The largest window on the screen is the 3D View

. This is where you work on your model.

. This is where you work on your model. - The Properties

window is the tall area on the right; this is where most of the functions are located for performing operations on models, materials etc. In previous versions of Blender this was called the Buttons window. Over time, it evolved into a disorganized area that made it difficult to find things. It has been cleaned up significantly in 2.5x. Note that it defaults to a vertical layout, rather than the horizontal one of previous versions. The new design prefers a vertical layout, which better suits today’s widescreen monitors.

window is the tall area on the right; this is where most of the functions are located for performing operations on models, materials etc. In previous versions of Blender this was called the Buttons window. Over time, it evolved into a disorganized area that made it difficult to find things. It has been cleaned up significantly in 2.5x. Note that it defaults to a vertical layout, rather than the horizontal one of previous versions. The new design prefers a vertical layout, which better suits today’s widescreen monitors. - The Outliner

(at the top right) gives you an overview of the objects in your document. As your models get more complex, you will start to appreciate the ability to quickly find things here.

(at the top right) gives you an overview of the objects in your document. As your models get more complex, you will start to appreciate the ability to quickly find things here. - The Timeline

(across the bottom) becomes important when you’re doing animation.

(across the bottom) becomes important when you’re doing animation.

The default layout may not be optimal. For example, if you’re doing a static model or scene, not an animation, you can get rid of the Timeline. If you’re doing heavy script development, you’ll probably want the Console available to try things out. And so on.

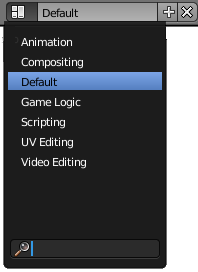

Workspace Presets

[edit | edit source]In the Info window/titlebar, you will see a menu with an icon like this ![]() . Clicking on it with LMB will show the following menu:

. Clicking on it with LMB will show the following menu:

Selecting from this menu lets you quickly switch between various predefined workspace layouts, tailored to various workflows. Try it and see. You can return to the default layout by selecting “Default” (but note that any changes you make to the layout are immediately associated with the name being displayed here). The menu has a search box at the bottom. Typing text here will restrict the menu to showing items containing only that text. It might not appear to have much use, but in a complicated project that needs dozens of different layouts, the search function could become very useful indeed!

The name of the currently selected item appears to the right of the menu icon. In the illustration above, this is "Default". Blender allows you to rename the current menu item by clicking on it with the LMB and typing a new name, so take care not to do so unless you actually want to rename the menu item. For example, if you replace the name "Default" with "MyDefaults", you will subsequently see that "MyDefaults" appears in the list of menu items.

Note also the “+” and “X” icons to the right of the menu; clicking “+” creates a new entry which is a duplicate of the last-selected entry, while clicking “X” gets rid of the currently-selected entry. You will see these conventions appear consistently in menus elsewhere in Blender’s new, revamped interface.

One Document At A Time

[edit | edit source]Blender can only work with one open document at a time (this does not apply to blender 2.79, which allows multiple instances of blender to run concurrently). To save changes to the current document, select one of the Save options from the File menu (or press Ctrl + S to save under the last-saved name). To open a new document (actually load a copy of your last-saved user preferences), select “New” from the File menu (or press Ctrl + N ), and select “Reload Start-Up File” from the popup that appears, but be aware this will not automatically save any changes to the previous document.

Scenes

[edit | edit source]A scene is like a separate Blender-document within-a-document. Different scenes within the same document can easily share objects, materials etc. You can define them once and make different renderings and animations from them. You create, delete and switch scenes using the scene ![]() menu in the info header. A new document starts by default with just one scene, called “Scene”.

menu in the info header. A new document starts by default with just one scene, called “Scene”.

Leaving Blender

[edit | edit source]To exit Blender:

- If there's a tool active, press Esc to exit the tool.

- Press Ctrl + Q . This brings up an OK? menu.

- Confirm Quit Blender by clicking LMB or pressing Enter .

|

In versions before 2.79, Blender will not prompt you to save your work. However, you can easily pick up where you left off by using File → Recover Last Session. |

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source]- YouTube video on Splitting and Joining Windows in 2.49 at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uYb1j8X-ulc

- YouTube video on Splitting and Joining Windows in 2.59 at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mGK1gwFhx9M

- the Blender Manual page on "window types" at http://wiki.blender.org/index.php/Doc:Manual/Interface/Window_types

- the Blender Manual page on "changing window frames" at system/Arranging frames http://wiki.blender.org/index.php/Doc:Manual/Interface/Window system/Arranging frames

User Preferences Windows

[edit | edit source]

|

|

Applicable Blender version: 2.80. |

In this module, we'll take a closer look at the Blender Preferences window.

Accessing Blender Preferences

[edit | edit source]To open the Blender Preferences window click Edit → Preferences...

In Blender 2.79, you will find it under File → User Preferences...

Configuring Your Preferences

[edit | edit source]In order to get to modeling and rendering sooner, this tutorial will cover only a few of the many user-settable preferences.

If you ever need to restore Blender to its factory settings, click File → Defaults → Load Factory Settings

Save & Load → Auto Save

[edit | edit source]As the name suggests, Auto Save automatically saves the current .blend after a specified period of time. You can turn this on and off using the checkbox labelled "Auto Save". You can also adjust the amount of time between each save, by adjusting the "Timer (Minutes)" field.

System → Undo Steps

[edit | edit source]By default, Blender remembers your last 32 actions and allows you to undo them one at a time by either pressing Ctrl + Z or by selecting a frame under Edit → Undo History. However, you can change the number of Undo Steps stored to remember more or less actions, in case you want to conserve memory or simply stay on the safe side. You can also use the Undo Memory Limit slider to specify the amount of RAM (in megabytes) used for storing the undo levels. In case you're not too worried about memory, you can set the Undo Memory Limit field to 0 to remove the memory limit.

Input → Numpad Emulation

[edit | edit source]Blender uses numberpad keys (such as NUM7 ) to control the 3D View and ordinary numeral keys (such as 7 ) to change layers. If you are working on a laptop or if you find the numberpad inconvenient, you can select Emulate Numpad to reassign the 3D View controls to the ordinary numeral keys.

Input → Emulate 3 Button Mouse

[edit | edit source]Blender makes significant use of all three buttons on a standard computer mouse. If you do not have a mouse with three buttons, enabling this setting will let you perform MMB -related actions with ALT + LMB

Keymap

[edit | edit source]In Blender 2.79 and earlier, Blender used right click for selection. However, in Blender 2.8, this was changed to left click on default, along with some changes to keyboard shortcuts for efficiency. To stay compatible with different users' preferences, three keymap presets are provided on installation: "Blender", the new default keymap, "Blender 27x", which includes very few changes compared to earlier versions, and "Industry Compatible", designed to be used by those coming from other 3D software, such as Maya and ZBrush

Since much of this book was written before the 2.8 update came out, you may find pages that still use the old "right click to select" option, along with some outdated keybinds. If you're following a lot of tutorials for Blender 2.79 or earlier, you can go into Keymap and select Blender 27x under the presets list. You can always switch back if needed.

Additional Resources

[edit | edit source]- The Blender manual pages on Preferences

- The tutorial on Non-standard Equipment describes other workarounds for numpad issues.

Properties Window

[edit | edit source]|

|

Applicable Blender version: 3.3. |

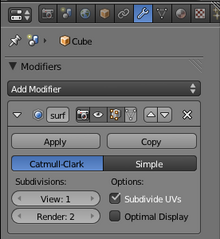

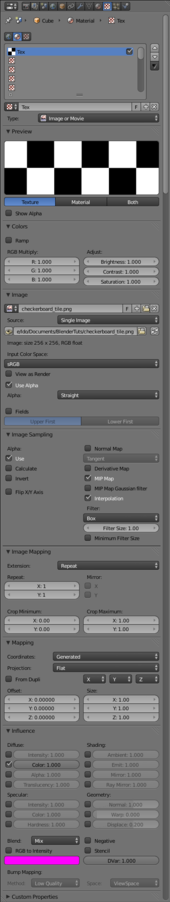

The properties window lets you change many settings and properties relating to the current scene and selected objects. You can edit many options, including customizing materials and textures, controlling how your scene is rendered and at what quality, among many other things.

The properties window is divided into categories, which themselves group individual tabs. Each tab, in turn, groups a selection of properties and settings. For example, the World Properties tab, under the Scene category, lets you control the color and texture of the background of the scene (i.e. the sky), and allows you to add volumetric effects to the scene (i.e. fog or mist). Each tab has their own, unique, icon. Some tabs will even change depending on the type of object selected!

Active Tool and Workspace settings