Structural Biochemistry/Volume 8

Nucleic Acids are long linear polymers that are called DNA, RNA. these polymers carry genetic information that passed from generations after generations. They are composed of three main parts: a pentose sugar, a phosphate group, and a nitrogenous base. Sugars and Phosphates groups play as structure of the backbone, while bases carries genetic components, which characterized the differences of nucleic acids. There are 2 types of bases: purines and pyrimidines, and these bases determine whether the nucleic acid is DNA or RNA.

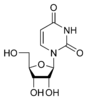

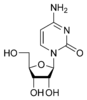

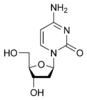

Nucleic acids are composed of smaller subunits called nucleotides. A nucleotide is a nucleoside with one or more phosphoryl group by esterlinkage. When it is in the form of RNA the bases are called adenylate, guanylate, cytidylate, and uridylate. In the form of DNA the bases are called deoxyadenylate, deoxyguanylate, deoxycytidylate, and thymidylate. A nucleoside is a monomer, just the bases attached to a sugar without the phosphate groups. In this state the bases in RNA are called adenosine, guanosine, cytidine and uridine. In this state in DNA the bases are called deoxyadenosine, deoxyguanosine, deoxycytidine and thymidine.

| This page or section is an undeveloped draft or outline. You can help to develop the work, or you can ask for assistance in the project room. |

In organic chemistry, a phosphate, or organophosphate, is an ester of phosphoric acid. Organic phosphates are important in biochemistry and biogeochemistry.

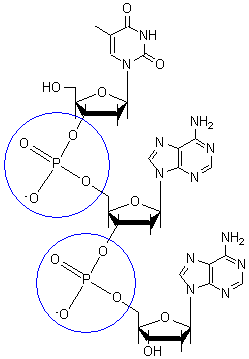

The backbone of the DNA strand is made from alternating phosphate and sugar residues. The sugars are joined together by phosphate groups that form phosphodiester bonds between the third and fifth carbon atoms of adjacent sugar rings.

As you noticed in the deoxyribose sugar, it does not contain a hydroxyl group on the 2' carbon. This absence of the hydroxyl group allows greater stability because the absence of hydroxyl group allows the 2' carbon to resist hydrolysis. This is one of the reasons why the hereditary material is stored in the DNA and not RNA. However, the net negative charge of the phosphate group must be stabilized by metal ions, such as magnesium or manganese.

Phosphodiester bond

[edit | edit source]In the molecular bonding of the deoxyribonucleotide (DNA) and ribonucleotide(RNA), phosphodiester bond is a strong covalent bond between a phosphate group and two 5-carbon ring. The phosphate group contains a negative charge as it bonds to a 3' carbon in one ring and a 5' carbon in another ring.

The phosphodiester is formed when a single phosphate or two phosphates break away and catalyze the reaction by DNA polymerase. dATP would dissociate one phosphates in order to form a phosphodiester bond with a deoxyribose sugar from a nucleotide during the process of DNA elongation.

(DNA)n + dATP <------> (DNA) n+1 + Ppi

Phosphodiesterase is an enzyme that breaks a cyclic nucleotide phosphate due to incorrect hydrolysis of phosphodiester bonds. Phosphodiesterase will be an important clinical significance in repairing DNA sequences.

Carbohydrates

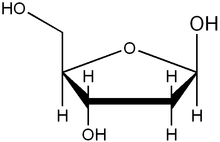

[edit | edit source]Carbohydrates are comprised of monosaccharide units which create sugars ranging from simplest of sugars such as glucose (chemical formula: C6H12O6) to the more complex polysaccharides such as starch. Single nucleotide monomeric units consist of one sugar molecule connected to 1) a heterocyclic nitrogen containing organic base, and 2) a Phosphate group that connects the sugar component of different nucleotides together. The organic base is usually attached to Carbon 1' of the sugar, while the Phosphate group is connected to Carbon 5' of the sugar. When strung together, the phosphate of the neighboring nucleotide attaches to Carbon 3' of the sugar.

Monosaccharides consist of aldehyde or ketone groups with hydroxyl groups as substituents. Sugars that contain an aldehyde group are called aldoses, and the sugars that contain a ketone group are called ketoses.

Sugars that are non-super imposable mirror images of each other are called enantiomers. Sugars that are stereoisomers but mirror images of each other are called diastereoisomers. If sugars that are stereoisomers but differ in configuration at a single chiral center are called epimers.

Sugars can be open-chain form or ring form. To form a six-membered hemiacetal ring, the carbon in the aldehyde group (C-1) attaches to the oxygen atom in the C-5 hydroxyl group. The six membered cyclic hemiacetal is called pyranose because it is similar to the structure of a pyran. To form a five-membered ring, the C-2 of ketone group attacks the oxygen atom of the hydroxyl group on C-6. The five membered cyclic hemiacetal is called furanose because it is similar to the structure of a furan. When a furanose or pyranose ring is formed, a new stereocenter is formed, and this new chiral carbon is called the anomeric carbon. This carbon can have one of two configurations, it is either in the S conformation (the hydroxyl group is pointing up), and it is referred to as the alpha carbon, or it is in the R conformation (the hydroxyl group is pointing down) and it is referred to as the B configuration. These two conformations are diastereomers, not enantiomers, and the α and β forms are called anomers.

A reducing sugar is one that can react because they have a relatively reactive hemiacetal group at C-1 position. Examples include: glucose, fructose, lactose, and maltose. The anomeric carbon in all of these molecules is free to react.

A non-reducing sugar is one that does not react, such as sucrose. The acetal group at the C-1 position makes the sugar non-reactive. Their structures are modified, so that they do not have free aldehyde or ketone groups to react. In sucrose, neither of the monosaccharides in the disaccharide can easily change into an aldehyde or ketone, making it nonreactive, this non-reducing. The glycosidic bond in the disaccharide hinders the molecule from being reactive. The anomeric carbon is not free to react. In order to determine whether or not a sugar is reducing, a Fehling's or Tollen's test is performed. In the Fehling's test a brick red precipitate is the positive result, and in the Tollen's test a silver mirror is the positive result.

In contrast, when a sugar is oxidized, the aldehyde or ketone carbonyl becomes a carboxyl group.

It is called an O-glycosic bond if the anomeric carbon is attached to an oxygen atom of a hydroxyl group. It is called an N-glycosidic bond if the anomeric bond is attached to a nitrogen atom of a amine group.

Glycosidic bonds are also what form the bridges between monosaccharides. If monosaccharides are joined by O-glycosidic bonds, they are called oligosaccharides.

The difference in having an -OH group attached to Carbon 2' of the sugar is the difference between DNA and RNA. In RNA, the carbon 2' contains an -OH group, whereas in the carbon 2' of DNA, there is just a hydrogen attached. The sugar in RNA, or "ribonucleic acid" is "ribose" while the sugar for DNA or "DEOXIribonucleic acid" is "deoxiribose." DEOXI- is used to represent the lack of oxygen from the -OH group on Carbon 2' of ribose.

| ||

||

Importance of sugar in glycoproteins

Sugar attached proteins called glycoproteins is another important component of the cell. Sugar components are oriented toward the watery cell exterior of glycoproteins. These sugar components serve as an identifier like cellular address labels. When signaling molecules pass through bodily fluids they encounter certain patterns of sugars, which either gives them access or dismissal. Therefore, the glyoproteins act as a regulator or gatekeeper in cells. In addition they help direct the formation of organs and tissue by forming correct cells together. Sugar coatings also help cells move through blood vessels by providing traction by latching on cell surface receptors.

References

[edit | edit source]Davis, Alison. "The Chemistry of Health." 'NIGMS August 2006: 36-42. http://publications.nigms.nih.gov/chemhealth/coh.pdf

| This page or section is an undeveloped draft or outline. You can help to develop the work, or you can ask for assistance in the project room. |

Structural Biochemistry/Nucleic Acid/Sugars/Deoxyribose sugar

| This page or section is an undeveloped draft or outline. You can help to develop the work, or you can ask for assistance in the project room. |

Ribose primarily occurs as D-ribose. It is an aldopentose, a monosaccharide containing five carbon atoms that has an aldehyde

functional group at one end. Typically, this species exists in the cyclic form. Ribose composes the backbone for RNA and relates to deoxyribose, as found in DNA, by removal of the hydroxy group on the 2' Carbon.

Ribose is less resistant to hydrolysis and will cause tension in RNA due to the negative charge of the phosphodiester bridge and the hydroxyl group on the 2' Carbon. The hydroxyl group has the capability to attack the phosphodiesr bond that typically links it to another ribose, thereby forming a cyclic form of the sugar. An example of this is cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate (cAMP).

Roles of D-ribose in the body

[edit | edit source]Aside of being the backbone for RNA and DNA, D-ribose is also important in the creation of ATP that all cells require to stay alive. It is currently used in medicinal practice to increase muscle energy and improve exercise performance. People that experiences Fibromyalglia and chronic fatigue syndrome that took a supplement of D-ribose improved their conditions dramatically. D-ribose supplements improved their conditions because it helps the patients produce more ATP in the body, because their body cannot produce a sufficient amount of ATP needed.

D-ribose has an important role in improving heart function for patients that suffer symptoms of congestive heart failure (CHF). Ischaemia, which is sudden decrease of blood supply, reduces myocardial ATP level. The addition of D-ribose will replenish the ATP level because it shortens the time it takes to create and restore ATP levels. Therefore the patient will be able to last longer during exercising before experiencing left chest pain, because the body is getting adequate amount of myocardial ATP. It also aided in regulating blood circulation in the heart by normalizing and readjusting blood flow through the left ventricle and atrium to accommodate the sudden change in blood supply. As a result patients suffering from CHF has an improved quality of life after taking D-ribose supplements because they are able to do more physical activity and return to a near normal lifestyle.

D-Ribose supplement is also important to athletes as well because it quickly replenishes ATP levels in muscle to help increase stamina and aid in strength building. D-ribose shorten the time it takes to create ATP because it directly enter the pentose phosphate pathway to create ribose-5-phosphate without having to go through the glucose-6-phospohate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, both of which require rate-limiting enzymes to form. The rate-limiting enzyme will slow down the creation of ATP, therefore by bypassing those pathways ATP will be produced at a higher rate. Hence, it restores ATP that was loss during exercise faster.

Summary of the roles:

1. Provide a backbone for DNA and RNA

2. Restores ATP in the body

3. Improve muscle stamina

4. Regulate blood circulation in the heart.

Natural sources of D-Ribose

[edit | edit source]D-ribose is a molecule that is naturally produced by the human body and is not found in food sources. However riboflavin, a component of d-ribose that helps aid in the production of d-ribose, is found in a plethora of food. Riboflavin, also known as vitamin B2 is found in found in eggs, milk products, nuts, vegetable, beef, and other proteins. However, these should be kept in areas where it is dimly lit because light can damage riboflavin.

Riboflavin

[edit | edit source]Aside from helping form d-ribose, riboflavin also helps fight off free radicals that can be damaging to cell. Hence it is also a form of antioxidant for the body. Free radicals can damage cells and increase aging and contribute to health conditions, such as heart disease and cancer, therefore riboflavin aids in the reduction of free radicals found in one’s body. Another function of riboflavin is that it helps produce red blood cell and convert B6 vitamin into a form the body can use. Another function of riboflavin is that it helps skin develop properly.

Summary of roles:

1. Helps form ribose that is then converted to d-ribose

2. Acts as an antioxidants

3. Helps produce red blood cells.

4. Convert B6 vitamin into a form the body can use.

5. Helps develop skin properly.

References

[edit | edit source]1. http://eurjhf.oxfordjournals.org/content/5/5/615.long

2. http://www.super-smart.eu/en--Sports-Endurance--D-Ribose--0477

3. http://www.livestrong.com/article/492628-natural-sources-of-d-ribose/

4. http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/vitamin-b2-000334.htm

5. http://www.webmd.com/vitamins-supplements/ingredientmono-957-RIBOFLAVIN%20(VITAMIN%20B2).aspx?activeIngredientId=957&activeIngredientName=RIBOFLAVIN%20(VITAMIN%20B2)

Overview

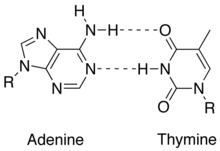

[edit | edit source]A DNA nucleotide is composed of 3 main units: a 5-carbon monosaccharide (deoxyribose), a phosphate group, and a nitrogenous base. While the monosaccharide and phosphate group alternate in sequence and form the backbone of the DNA double helix, the nitrogenous bases may differ in every adjoining nucleotide. The four nitrogenous bases present in DNA are adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C) and thymine (T). In RNA, the only differing nitrogenous base is uracil (U) (which replaces thymine in DNA and differs thymine only by the missing methyl group at carbon 5 of the pyrimidine ring). Of the nitrogenous bases, adenine and guanine are purines, which are aromatic compounds attached to an imidazole group, while cytosine and thymine and uracil compose a set of pyrimidines, which are one ring-aromatic compounds. Nitrogenous bases, being hydrophobic, tend to face inwards of the double helix, pointing away from the surrounding aqueous environment. If the phosphate backbones were faced inside of the double helix, then there will be too many charges clustered together such that the double helix would be an unlikely product. Bonds between linking nitrogenous bases of two DNA strands are Hydrogen bonds with 3 H-bonds connecting cytosine and guanine and 2 H-bonds connecting adenine and thymine, while the bonds between the stacking of DNA are kept in close contact via van der waals interactions. The aromaticity of the nitrogenous bases accounts for the DNA absorbance peak at 260nm.

== What is a Purine? ==

| This book's factual accuracy is disputed. |

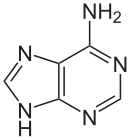

The name was invented by the German chemist Emil Fischer in 1884. A purine is a nucleotide (a nucleoside + phosphate group) that is amine based and planar, aromatic, and heterocyclic. The structure of purine is that of a cyclohexane(pyrimidine group) and cyclopentane(imidazole group) attached to one another; the Nitrogen atoms are at positions 1,3,7,9. Adenine(A) and Guanine(G) are examples of purines which are involved in the construction of the backbone of the DNA and RNA. They are also a part of the structures for Adenosine disphosphate (ADP), triphosphate(ATP), and other enzymes. Purines form bonds with pentoses exclusively through the 9th Nitrogen atom.

6-amino and 2-amino-6-oxy purine

[edit | edit source]One derivative form of purine, adenine (A), is also commonly known as 6-amino purine. The 6-amino purine molecule contains an amine group attached to the carbon atom at position 6 double bonded to the nitrogen atom at position 1 and single-bonded the carbon atom at position 5. Another derivative form of purine, guanine (G), is also known as 2-amino-6-oxy purine. The 2-amino-6-oxy purine contains an amine group attached to the carbon atom at position 2 double bonded to the nitrogen atom on position 3 and single-bonded to the nitrogen atom on position 1. Guanine also has a carbonyl group at position 6 hence the 6-oxy.

Purine content in foods

[edit | edit source]Food is responsible for approximately 30% of uric acid in the blood. Regular diets could affect the level of uric acid. Some food will increase the blood acidity even if the content in purine is low.

Lowest level of Purine: 0–50 mg

[edit | edit source]tea, coffee, soda, nuts, dairy products, vegetables, cereal, fruits, preserve foods, sweets

Moderate level of purine: 50–150 mg

[edit | edit source]spinach, avocado, beef, turkey, lamb, oyster, fish, peanuts, sausages, ducks, chickens

High level of purine: 150–1000 mg

[edit | edit source]kidney, liver, heart, caviar, scallops, lobster, sardines, Thai fish sauce

Risks

[edit | edit source]A diet high in purines can lead to gout, a form of arthritis with symptoms of severe pain, redness, and swelling. Uric acid is a product formed from the breakdown of purines. Uric acid builds up in one's joints, causing the inflammation and resultant pain.

2 Types of Purine Disorders of Nucleotide Synthesis

[edit | edit source]Adenylosuccinase deficiency

[edit | edit source]This causes retardation or heart attacks due to high level of succinyladenosine in urine. Currently, there is no treatment.

Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase superactivity

[edit | edit source]A recessive disorder which causes too much production of purines, which results in gout or other developmental effects. Treatments could include low purines in daily diet.

Functions

[edit | edit source]Purines are biochemically significant in a myriad of biomolecules besides DNA and RNA, such as ATP, GTP, cyclic AMP, NADH, and coenzyme A. Although purine has not been found naturally in nature, it can be produced through organic synthesis. Purines can also be used as neurotransmitters, acting upon purinergic receptors (i.e., adenosine activates adenosine receptors)

Metabolism

[edit | edit source]Many organisms utilize metabolic pathways in order to synthesize and break down purines. Biologically, purines are synthesized as nucleosides, which are bases attached to ribose.

Laboratory Synthesis

[edit | edit source]Purines can be created artificially, too, and not just through vivo synthesis in purine metabolism. When formamide is heated in an open vessel at 170°C for 28 hours, purine is obtained.

Procedure

[edit | edit source]1. Obtain a sample of formamide

2. Heat in an open vessel with a condenser for 28 hours in an oil bath at 170-190°C

3. Remove excess formamide through vacuum distillation

4. Reflux the residue with methanol

5. Filter the methanol solvent and remove by vacuum distillation

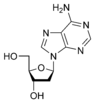

Adenine

[edit | edit source]

Structure & Function

[edit | edit source]Adenine(A) is one of the four bases that make up nucleic acids. It is a purine base that complementarily binds to Thymine (T) in DNA and Uracil (U) in RNA. This bond is formed by two hydrogen bonds, which help stabilize the nucleic acid structures. Different structures of adenine mainly result from tautomerization of adenine, which allows the molecule to be available in isomeric forms in chemical equilibrium. The molecular formula of adenine is C5H5N5 .

An adenine molecule bound to a deoxyribose, a sugar, is known as deoxyadenosine. An adenine bound to ribose, also a sugar, is known as adenosine, a key component in Adenosine Triphosphate. When adenosine attaches to three phosphate groups, a nucleotide, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is formed. Adenosine triphosphate is an important source of energy that is used in many cellular mechanisms, primarily in the transfer of energy in chemical reactions. The phosphate of ATP can detach, resulting in a release of energy.

In addition to ATP, adenosine also plays a key role in other organic molecules nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), both molecules of which are involved in metabolism. Also, adenine can be found in tea, vitamin B12, and several other coenzymes.

Formation and other forms of Adenine

[edit | edit source]In the human body, adenine is synthesized in the liver. Biological systems tend to preserve energy, so usually adenine is achieved through the diet, the body degrading nucleic acid chains to obtain individual bases and reconstructing them through mitosis. The vitamin folic acid is important for adenine synthesis.

Adenine forms adenosine, a nucleoside, when attached to ribose, and deoxyadenosine when attached todeoxyribose; it forms adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a nucleotide, when three phosphate groups are added to adenosine. Adenosine triphosphate is used in cellular metabolism as one of the basic methods of transferring chemical energy between reactions.

In older literature, adenine was sometimes called Vitamin B4. However it is no longer considered a true vitamin (see Vitamin B). Some think that, at the origin of life on Earth, the first adenine was formed by the polymerizing of 5 hydrogen cyanide (HCN) molecules.

Biosynthesis

[edit | edit source]Adenine is one of the byproducts of the Purine metabolism, where inosine monophosphate (IMP) is synthesized with a pre-existing ribose through a complex process involving atoms from the amino acids glycine, glutamine, and aspartic acid, in addition to the formate ions transferred from coenzyme tetrahydrofolate.

]== Tautomerization ==

Tautomers are isomers related by changing the positions of attachment of a single hydrogen and a single double bond, in a three-atom system, such as the keto- and enol tautomers of a ketone. Like, keto-enol tautomers, Adenine, as well as Cytosine, Guanine, Tyrosine, and Uracil may go through tautomerization, interchanging from the amino to the imino functionality by intermolecular proton transfer.

File:Http://i.imgur.com/l0lfQ.gif

Uracil

File:Http://i.imgur.com/yTNRT.gif

Cystein

File:Http://i.imgur.com/1hwJR.gif

Guanine

File:Http://i.imgur.com/WGmXH.gif

Thymine

File:Http://i.imgur.com/l0lfQ.gif

Uracil

File:Http://i.imgur.com/yTNRT.gif

Cystein

File:Http://i.imgur.com/1hwJR.gif

Guanine

File:Http://i.imgur.com/WGmXH.gif

Thymine

Reference

[edit | edit source]http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-233827562.html http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Structural_Biochemistry/Nucleic_Acid/Sugars/Deoxyribose_Sugar http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Structural_Biochemistry/Nucleic_Acid/Sugars/Ribose http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Structural_Biochemistry/Nucleic_Acid/Phosphate

Guanine

[edit | edit source]

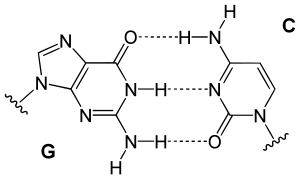

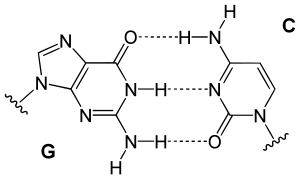

Guanine is among the five nucleobases that is found in DNA and RNA. The formula of guanine is C5H5N5O, and is a planar and bicyclic molecule. Guanine has two forms, keto and enol forms. The keto form is the major form. Guanine, like adenine, is a derivative of purine and binds to cytosine through 3 hydrogen bonds. The amino group in the cytosine is the hydrogen donor and the C2 carbonyl and the N3 amine are the hydrogen-bond acceptors. In Guanine, the group at C6 acts as the hydrogen accepter, and the group at N1 and the amino group at C2 act as the hydrogen donors. The related nucleoside containing guanine and ribose is called guanosine and guanine bound to deoxyribose sugar is called deoxyguanosine.

Guanine is capable of being hydrolyzed by strong acids to form ammonia, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and glycine. Guanine oxidizes more readily than adenine, another purine-derivative nitrogenous base in nucleic acids. Guanine has a high melting point of 350°C due to the intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the oxo and amino groups in the crystal of the molecule. Also because of this intermolecular bonding, guanine is relatively insoluble in water as well as in weak acids and bases.

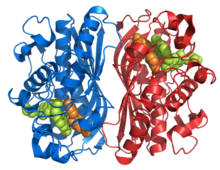

DNA base pair bonding

[edit | edit source]

From the image on the left, it can be seen that Guanine and Cytosine bond together through noncovalent hydrogen bonding at three distinct sites. Since Cytosin to Guanine has 3 H-bonds and Adenine to Thymine has 2 H-bonds, a higher CG content leads to higher melting point when compare with AT content. An interesting note is that Watson and Crick first hypothesized that Guanine and Cytosine bonded together through hydrogen bonding at two distinct sites. [1]

Tautomerization

[edit | edit source]Guanine may go through tautomerization, interchanging from the keto to the enol functionality by intermolecular proton transfer.

Miscellaneous

[edit | edit source]Guanine is also the name of the white amorphous substance found in fish scales. It serves as an additive to various products such as shampoos, metallic paints, and simulated pearls and plastics providing a pearly iridescent effect. Also, it adds a shimmering luster to eye shadow and nail polish. This pearly luster is produced by the crystalline form of guanine which are rhombic platelets composed of multiple transparent layers that have a high index of refraction that partially reflects and transmits light from layer to layer. To provide this effect, it can be applied by spraying, painting, or dipping.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Crick, Francis H. (1953). "Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids". Nature. 171: pp. 737-738.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Berg, Jeremy M. John L. Tymoczko. Lubert Stryer. Biochemistry Sixth Edition. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, 2007.

| This page or section is an undeveloped draft or outline. You can help to develop the work, or you can ask for assistance in the project room. |

Purine is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound. Purine consists of a pyrimidine ring fused to an imidazole ring. Purines and pyrimidines make up of two groups of nitrogenous bases. The name was invented by the German chemist Emil Fischer in 1884. Below are the DNA bases.

Hypoxanthine

[edit | edit source]Hypoxanthine (6-Hydroxypurine) is a naturally occurring purine derivative and deaminated form of adenine. It is an intermediate in the purine catabolism reaction and is occasionally found as a constituent in the anticodon of tRNA as the nucleosidic base inosine. It is also utilized as a nitrogen source in bacteria and parasite cultures for energy metabolism and nucleic acid synthesis.

Reactions

[edit | edit source]Hypoxanthine exists as an intermediate in the biodegradation of AMP (adenosine monophosphate). It is first converted to xanthine with xanthine oxidase before it is excreted as urate.

A deleterious reaction that can occur is a spontaneous deamination of adenine to form hypoxanthine. This is a mutagenic process because the result is a pairing of hypoxanthine with cytosine rather than thymine, due to hypoxanthine’s guanine-like form. This could lead to an error in DNA transcription and replication.

References

[edit | edit source]Berg, et al. Biochemistry, 6th Ed. 2007.

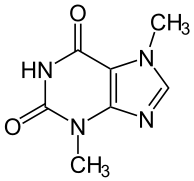

Xanthine

[edit | edit source]Xanthine is a purine base that's an antecedent of uric acid and is generally found in muscle tissue, blood, urine and some plants. It is a water insoluble toxic yellowish white powder and acids that's soluble in caustic soda; it sublimes when heated. It is involved in purine degradation and is converted from hypoxanthine and converted to uric acid by xanthine oxidase. Some of its derivatives are widely known as mild stimulants, which include caffeine, a sleep-inhibiting methylated xanthine found in coffee, and theobromine, a bitter alkaloid found in cacao.

Diseases

[edit | edit source]There is a genetic disease of xanthine metabolism, xanthinuria, due to deficiency of an enzyme, xanthine oxidase. Xanthinuria is a rare genetic disorder where individuals are unable to convert xanthine into uric acid because of the lack of enzyme xanthine oxidase resulting in an accumulation of xanthine. Symptoms include renal failure and kidney stones. There is currently no treatment available to cure this disease.

Clinical Use

[edit | edit source]Xanthine derivatives are collectively known as xanthines, which are a group of alkaloids used as stimulants and bronchodilators. As a result of widespread side effects, many of these derivatives have been treated as second-rate asthma treatment medication.

References

[edit | edit source]Berg, et al. Biochemistry, 6th Ed. 2007.

Theobromine

[edit | edit source] Theobromine (xantheose) is a xanthine derivative and bitter alkaloid commonly found in cacao plants. Its name is derived from the name of the genus of the cacao tree. It doesn’t contain bromine, as its name might indicate. It shares a similar structure to that of another well-known purine and xanthine derivative known as caffeine, except it contains one more methyl group. It was first discovered in the cacao plant in 1841, isolated in 1878, and synthesized from xanthine by Hermann Emil Fischer shortly thereafter. In its pure form, it is a water-insoluble, crystalline white powder that has a milder effect than caffeine. Since dark chocolate has higher concentrations of theobromine than milk chocolate, its beneficial effects are better attained from the less diluted dark chocolate.

Theobromine (xantheose) is a xanthine derivative and bitter alkaloid commonly found in cacao plants. Its name is derived from the name of the genus of the cacao tree. It doesn’t contain bromine, as its name might indicate. It shares a similar structure to that of another well-known purine and xanthine derivative known as caffeine, except it contains one more methyl group. It was first discovered in the cacao plant in 1841, isolated in 1878, and synthesized from xanthine by Hermann Emil Fischer shortly thereafter. In its pure form, it is a water-insoluble, crystalline white powder that has a milder effect than caffeine. Since dark chocolate has higher concentrations of theobromine than milk chocolate, its beneficial effects are better attained from the less diluted dark chocolate.

Therapeutic uses

[edit | edit source]Theobromine is known as a diuretic, which promotes the removal of excess fluids accumulated in the body from edema, or the flushing of excess salts through the increase production of urine.

It is also widely used as a vasodilator, which widens blood vessels and improves blood flow. This, in turn, helps reduce blood pressure, although it is reputed that flavanols have a bigger role in promoting that effect.

A 2004 patent on the future use of theobromine for cancer prevention was granted due to recent research that revealed anti-carcinogenic activity.

Effects

[edit | edit source]Humans

[edit | edit source]Theobromine has a weaker effect on the human central nervous system than caffeine because of its weaker inhibition effects on cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases and its antagonism of adenosine receptors. As for its effect on the heart, theobromine stimulates it to a much greater degree than caffeine. It is cited as being involved in contributing to chocolate’s role as an aphrodisiac.

Since theobromine is a myocardial stimulator, it increases the heartbeat. As stated above it also dilates blood vessels and reduces blood pressure by enlarging the vessels. It is possible that theobromine might be able to treat cardiac failure since it has properties which allowing draining. Ingesting too much theobromine could lead to some adverse effects. Since it is a diuretic, it will increase the amount of urine produced in the person. It could also possible cause nausea, restlessness, sleeplessness, and anxiety.

Poisoning

[edit | edit source]A helpful hint in responsible pet-keeping is to not feed dogs or cats cacao containing products. This is because they metabolize theobromine much more slowly than humans. Complications that arise from doing such an action is succumbing your pet to theobromine poisoning, which causes digestive issues, dehydration, excitability, and a slow heart rate. Larger quantities of theobromine can result in epileptic-like seizures and even death.

What is a Pyrimidine?

[edit | edit source]A pyrimidine is a 6-membered heterocyclic organic compound made up of 4 carbon atoms and 2 nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3.[1] It is one of three isomers of diazine, the other two being pyridazine (1,2-diazine), and pyrazine (1,4-diazine).[2] Pyrimidines are aromatic and planar. The nucleobases Cytosine(C), Uracil(U), and Thymine(T) are all examples of pyrimidines; each with different chemical groups. Pyrimidines can attach to a phosphate sugar group such as a ribonucleotide(which have a hydroxy group positioned axially at carbon-2) or deoxyribonucleotide(which have a hydrogen atom at C-2) through a glycosidic linkage at the 1st Nitrogen to form a nucleotide, the monomeric building block of nucleic acids (DNA and RNA).

Correct mistake:

2. It needs carbonyl phosphate synthetase, which is located in the cytoplasm.

Pyrimidine Biosynthesis

[edit | edit source]1. Unlike in purine, the ring is synthesized first then conjugated after.

2. It needs carbamoyl phosphate synthetase, which is located in the cytoplasm.

3. It also needs an enzyme in order for the reaction to work, but the enzyme should be controlled in 2 steps:

- controlled level at where the reaction occurs & transcriptions must be reduced

- the pyrimidine nucleotides which produces the feedback inhibition level also must be controlled

4. The ring then closes.

5. The C-C bond is formed when the ring oxidizes.

Chemical Properties

[edit | edit source]Pyrimidine has similar properties to that of pyridines. One similarity is that as the number of nitrogen atoms in the ring increase, the ring pi electrons become less energetic and, as a result, electrophilic aromatic substitution gets more difficult while nucleophilic aromatic substitution gets easier. One example is the displacement of the amino group in 2-aminopyrimidine by chlorine and its reverse reaction. Reduction in resonance stabilization of pyrimidines leads to the addition and ring cleavage reactions, and not substitutions. An example of this is in the Dimroth arrangement. Pyrimidines are less basic than pyridines and the N-alkylation and N-oxidation are more difficult in pyrimidines as well.

Cytosine

[edit | edit source]Cytosine is part of the pyrimidine family, and it is one of the 5 nucleotide bases found in both DNA and RNA. The molecular formula of cytosine is C4H5N3O. Cytosine consists of a heterocyclic aromatic ring, an amine group at C4, and a keto group at C2. Cytosine binds with ribose to form the nucleoside cytidine and with deoxyribose to form deoxycytidine.

The molecule is of planar geometry and cytosine forms 3 hydrogen bonds with Guanine in the DNA double helix. The nucleoside of cytosine is cytidine in RNA, which consists of cytosine and ribose. In DNA, it is called deoxycytidine, which consists of cytosine and deoxyribose. The nucleotide of cytosine in DNA is deoxycytidylate which consists of a cytosine, ribose and phosphate.

History

[edit | edit source]In 1894, Cytosine was discovered by the hydrolysis of the calf thymus tissue. The first structure for cytosine was published in 1903 and the structure was validated when it was synthesized that same year.(The Columbia Encyclopedia)

Chemical Activity

[edit | edit source]

From the image on the left, it can be seen that Guanine and Cytosine bond together through noncovalent hydrogen bonding at three distinct sites. An interesting note is that Watson and Crick first hypothesized that Guanine and Cytosine bonded together through hydrogen bonding at two distinct sites. [3]

Cytosine is found in DNA and RNA or as a part of a nucleotide. When the nucleoside cytidine binds with three phosphate groups, it forms cytidine triphosphate (CTP). This molecule can act as a co-factor to enzymes and it aids in transferring a phosphate to convert adenosine diphosphate (ADP) to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to prepare the ATP to be used in chemical reaction.

In DNA and RNA, cytosine binds with guanine through 3 hydrogen bonds. However, this unit is unstable and can change into uracil. This process is called spontaneous deamination. This can possibly lead to a point mutation if DNA repair enzymes such as uracil glycosylase does not repair it by cleaving uracil in DNA.

Tautomerization

[edit | edit source]Cytosine may go through tautomerization, interchanging from the amino to the imino functionality by intermolecular proton transfer.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128144534000194

- ↑ https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=physicsuiterwaal

- ↑ Crick, Francis H. (1953). "Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids". Nature. 171: pp. 737-738.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Berg, Jeremy M. John L. Tymoczko. Lubert Stryer. Biochemistry Sixth Edition. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, 2007.

CYTOSINE. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition

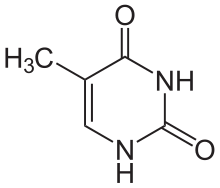

Uracil

[edit | edit source]Uracil is among the five nucleobases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine,but is only found in RNA. It is a naturally occurring pyrimidine derivative with the molecular formula C4H4N2O2. Uracil is planar and unsaturated and has the ability to absorb light.

Properties

[edit | edit source]Uracil is found in RNA and binds to adenine via 2 hydrogen bonds, but is replaced by thymine in DNA. Methylation of Uracil produces thymine. Uracil can pair with any of the base pairs depending on arrangement. Despite this, it readily pairs with adenine because the methyl group is repelled into a fixed position. In the uracil and adenine bond, uracil is the hydrogen bond acceptor and the adenine is the donor. When attached to a ribose sugar, the compound is called uridine, a nucleoside. Then, phosphate attaches to uridine to form uridine 5'-monophosphate. Nucleotides are formed through a series of phosphoribosyltransferase reactions. This produces substrates, aspartate, carbon dioxide, and ammonia.

Uracil, like other bases, undergoes tautomerization. The keto tautomer is referred to as the lactam structure, while the imidic acid tautomer is referred to as the lactim structure. With the lactam structure being the major form of uracil, both tauotemric forms are present under conditions where pH=7.

Uracil is a weak acid.

Chemical Activity

[edit | edit source]Uracil is capable of undergoing reactions such as oxidation, nitration, and alkylation. It can also react with elemental halogens because of the presence of more than one strongly electron donating group. A useful property of uracil is that in the presence of PhOH/NaOCl, it can be visualized in the blue region of UV light.

As stated above, uracil can partake in synthesis, binding with ribose sugars and phosphates to form very useful molecules like uridine, urindine monophosphate (UMP), urindine diphosphate (UDP), urindine triphosphate (UTP).

History

[edit | edit source]Uracil is a nucleotide that was discovered in the 1900s by the hydrolysis of yeast(Brown 1994). Uracil is an important component in helping enzymes to carry out different reactions and the making of polysaccharides (New World Encyclopedia). Because Uracil helps enzymes carry out different reactions in cells, it is important in the drug industry because it helps with delivering drugs throughout the body. Even though it is useful in helping the delivery of drugs in the body, it can increase the risk of cancer when the body is missing the nutrient folate (The Individualist). Uracil is naturally occurring however, it could also be synthesized in the laboratory by mixing water with cytosine. This reaction will produce two compounds which are uracil and ammonia(Wikipedia).

Tautomerization

[edit | edit source]Uracil may go through tautomerization, interchanging from the keto to the enol functionality by intermolecular proton transfer due to rich electrons ring.

References

[edit | edit source]New World Encyclopedia. Uracil. "http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org./entry/Uracil." 17 November 2008.

Wikipedia. Uracil. "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uracil." 17 November 2008.

Brown, D.J. Heterocyclic Compounds: Thy Pyrimidines. Vol 52. New York: Interscience, 1994.

The Individualist. Uracil. "http://www.dadamo.com/wiki/wiki.pl/Uracil." 17 November 2008.

Thymine

[edit | edit source]5th carbon, hence the other name of thymine, 5-methyluracil. Uracil takes its place in RNA, which also binds to adenine. Thymine is a single ring planar molecule. Thymine combined with deoxyribose yields deoxythymidine while Thymine with ribose makes thymidine.

Thymine binds with deoxyribose to form the nucleoside deoxythymidine, which is the same thing as thymidine. This compound can be phosphorylated with one, two, or three phosphoric acid groups creating thymidine mono-, di-, or triphosphate, respectively.

Thymine is a part of one of the most common mutations of DNA, which involves two adjacent thymines or cytosines. In the presence of UV light, this may form thymine dimers, causing "kinks" in the DNA molecule, interfering with normal function.

Uses of thymine include cancer treatment where it serves as a target for actions of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Substitution of this compound to thymine (in DNA) and uracil (in RNA) allows inhibition of DNA synthesis in actively-dividing cells.

Properties

[edit | edit source]Thymine is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound as a pyrimidine nucleobase. Heterocyclic compounds are organic compounds (those containingcarbon) that contain a ring structure containing atoms in addition to carbon, such as sulfur, oxygen, or nitrogen, as part of the ring. Aromaticity is a chemical property in which a conjugated ring of unsaturated bonds, lone pairs, or empty orbitals exhibit a stabilization stronger than would be expected by the stabilization of conjugation alone.

As the name implies, thymine may be derived by methylation of uracil at the fifth carbon. In DNA, thymine(T) binds to adenine (A) via two hydrogen bonds to support in stabilizing the nucleic acid structures.

Thymine jointed with deoxyribose creates the nucleoside deoxythymidine, which is identical with the term thymidine. Thymidine can be phosphorylated with one, two, or three phosphoric acid groups, creating TMP, TDP or TTP (thymidine mono- di- or triphosphate) correspondingly.

One of the common mutations of DNA involves two neighboring thymine or cytosine, which in existence of ultraviolet light may form thymine dimers, causing "kinks" in the DNA molecule that constrain normal function.

Thymine could also be a goal for actions of 5-fu in cancer treatment. 5-fu can be a metabolic analog of Thymine (in DNA synthesis) or Uracil (in RNA synthesis). Replacement of this analog inhibits DNA synthesis in actively dividing cells.

Tautaumerization

[edit | edit source]Thymine may go through tautaumerization, interchanging from the keto to the enol functionality by intermolecular proton transfer.

References

[edit | edit source]Al Mahroos, M., et al. “Effect of sunscreen application on UV-induced thymine dimers.” Arch Dermatol 138: 1480-5, 2002. Ribonucleotide reductase (or RNR) is the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the reduction of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides. These deoxyribonucleotides can then be utilized by the cell in DNA replication. Additionally, because of the role RNR plays in the formation of deoxyribonucleotides, RNRs are responsible for regulating the rate of DNA synthesis within the cell.[1]

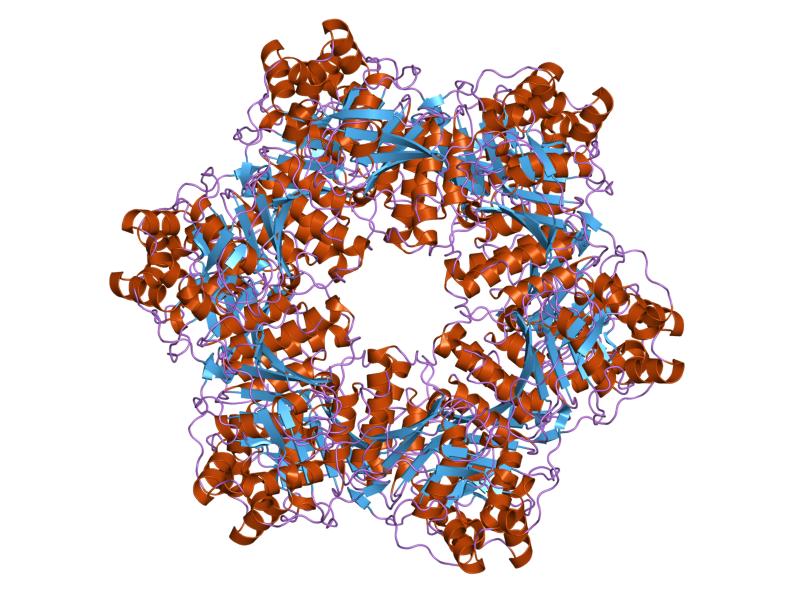

Classes of RNR[2]

[edit | edit source]- Class I: Class I RNRs consist two subgroups (Ia, Ib, and Ic) which differ only slightly in primary structure; however, both subgroups are common in that they contain two different dimeric subunits (R1 and R2) and require oxygen in order to form a stable radical. Class Ic RNRs are the most recently discovered, first found in Chlamydia trachomatis. Evidence also suggests its existence in archaea and eubacteria. The sequence of class Ic RNRs shows that residues in the PCET pathway and active site for nucleotide reductase are similar between the three subgroups.[3]

- Class II: Class II RNRs form thiyl radicals with the help of adenosylcobalamin – which fulfills the role of the R2 subunit as a radical generator – and utilize thioredoxin or glutaredoxin as electron donors. Therefore, class II RNRs are made up of only one subunit and present as monomers or dimmers and neither require nor are inhibited by the presence of oxygen.

- Class III: Class III RNRs, like Class I RNRs, are made up of two dimeric protein subunits (NrdG and NrdD); however, unlike in Class I RNRs which require R2 continuously to generate radicals, the small NrdG is only required during the activation of NrdD. The mechanism of Class III RNRs uses formate as an electron donor and generates an oxygen-sensitive glycyl radical, thus rendering the enzymes inactive in the presence of oxygen.

Radical Mechanism of RNR

[edit | edit source]Despite the differences in structure and electron donor, all three classes of RNR proceed via a free radical mechanism.[4] Ultimately RNR catalyzes a reaction which results in the replacement of the 2'-hydroxyl group of the ribose with a hydrogen atom resulting in a deoxyribose moiety.

Metallocofactor Assembly in Class I RNR[5]

[edit | edit source]Although the Class I RNR’s (Ia, Ib, and Ic) have comparable structures and pathways, the metallocofactors necessarily involved in the activity of RNRs to catalyze the conversion of nucleotides to deoxynucleotides differ remarkably. The mechanisms which generate these cofactors, both in vitro and in vivo, and examining how damaged cofactors are repaired show the significance of each subgroup’s dependence on different cofactors. Studies of the pathways and activation of these metallocofactors have helped our understanding of how biology prevents mismetallation from occurring and configures cluster formation in high yields. All three class I RNR share a common catalytic mechanism in which the metal cofactor is involved directly or indirectly in the oxidation of the conserved cysteine in the active site of alpha to thiol radical S•). Class I RNR oxidation occurs by the Y• in Ia and Ib.

- Class IA: Class IA RNR requires a FeIIIFeIII-Y• cofactor. It is localized in β2 at the end of a hydrophobic channel, the supposed access route for O2 cluster assembly. In studies of E. coli, the in vivo process showed that incubation of apo-β2 of E. coli with FeII, O2, and reductant, resulted in self-assembly of the FeIIIFeIII-Y• cofactor. This process likely requires at minimum a single small protein or molecule to deliver FeII to apo-β2 and to deliver the extra reducing equivalent required to reduce O2 to H2O. This is also plausible because Ia RNRN binds MnII more tightly than FeII, thus requiring some type of chaperone protein to ensure proper metallation.

- Class IB: Class IB RNR is active with both FeIIIFeIII-Y• and MnIIIMnIII-Y• cofactors. The enzymes can form active FeIIIFeIII-Y• cofactors in vitro, but only the MnIIIMnIII-Y• cofactor was found to be relevant in vivo. The mechanism of this formation has been proposed to occur via oxidation of a MnIIMnII center by a flavoprotein known as NrdI, an oxidant created by reduction of O2. In E.Coli, studies have found that the manganese cofactor is induced when iron is at premature levels in the cell, pointing to the significance of manganese in this and other organisms. There is also an extent of organism-dependent variation in metal homeo-stasis to be considered which may help explain why some organisms rely on either cofactor more frequently.

- Class IC: Class IC RNR is unique from Class Ia and Ib RNRs due to its proposed bimetallocofactor, MnIVFeIII. The class Ic RNRs store a one-electron oxidizing equivalent in its metal cluster. In vitro self-assembly of Ic is similar to Ia and Ib in that it reacts with O2 and a reductant to form its respective MnIVFeIII cofactor; however, it differs in that it can also react with 2 equivalents of H2 O2 to form the active cofactor. The class Ic RNR has been isolated from its native organism in vivo, complicating its assembly as the two different metals have similar affinities for the protein. In vitro studies in C. trachomatis have shown the necessity of regulating levels of the metals, along with the order of addition.

There exists problems with proper metal loading within the three subunits of Class I RNR. In the class Ia RNR, it requires a FeIIIFeIII-Y• cofactor, but the protein tends to bind MnII more tightly than FeII. In e.coli, correct metallation of NrdB relies on the necessity of free MnII and FeII present, while iron chaperones are also present to overcome the preference to bind MnII. The issue in class Ib RNR is that it may bind to either FeIIIFeIII-Y• and MnIIIMnIII-Y• cofactors, but only the manganese cofactor was found to be relevant in vivo. Ib binding is dependent on the preference of individual organisms and the concentrations of each metal that they possess inherently. The class Ic RNR complicates metallocofactor assembly since it requires two different metals with similar affinities for the same protein. Regulation of both levels of the metal is important in order to prevent mismetallation and its success depends on the presence of both types of metals. In C. trachomatis, the absence of MnII or at a lower than required rate may lead to diiron cluster formation instead. Thus if these levels are not regulation, low activity and improper metallation occurs. In general, if there is trouble regulating the levels of any of the required metals in each class I RNR, this leads to low activity and improper metallation and ultimately DNA synthesis is affected.

Biosynthesis and Repair of Metal Cofactors in Class I RNR[6]

[edit | edit source]Certain general principles and challenges exist when studying the metllocofactor formation with different metals and levels of complexity, as summarized below. Physiological expression conditions are taken into account in studies of metalloenzymes to confirm if the form of protein studied in vitro is the same as its active form in vivo. Class I RNRs can control the concentration of the active metal cofactors through biosynthetic and repeair pathways.

- Cofactors of metal proteins are generated by specific biosynthetic pathways.

- The proteins involved in the biosynthetic pathway are often associated with the operon of the metalloprotein of interest, and certain factors can be analyzed by comparing genomic sequences.

- To facilitate the exchange of ligands and protein factors, metals are transferred in their reduced state.

- There exists a variety of protein factors which include: metal insertase or chaperone to deliver the metal to the active site, specific redox proteins which control the oxidation state of the metal, and GTPases or ATPases which aid in the folding and unfolding processes to allow the metal to be inserted in the active site.

- Due to biological redundancy that affect pathway factors, multiple deletions of genes are required in order to identify phenotypes within a gene deletion experiment.

- A hierarchy of metal delivery to proteins and its regulation is inferred but not completely understood.

- Compartmentalization (e.g. periplasm vs cytosol in prokaryotes) and affinities of proteins to bind certain metals preferentially are two likely factors that contribute to prevent mismetatallion at the cellular level.

- Several proteins have not been isolated from their native source and form heterologous expression systems and leading to mismetallation. Since the optimum level of activity is not fully known, incorrect clusters corresponding to low activity may not be recognized.

- Certain oxidants can cause damage to the metal clusters (e.g. NO and O2) and specific pathways are used in their repair.

- During changes of oxidaion states, protons are typically required for this metal oxidation. Ligands to metal binding can reorganize easily and rearrangement of the carboxylate ligands are critical to the cluster assembly process.

One of the biggest complications is that the metal required for activity is often not the metal that has the highest affinity for binding to a specific protein. The Irving-Williams series (MnII < FeII < CoII < NiII < CuII > ZnII) best describes the relative affinities of proteins for divalent metals, in addition to the dependence on the particular protein coordination environment where the binding takes place. For the latter metals in the series, chaperone proteins exist to aid their movement to the active sites, while intracellularly they are likely to exist as "free" metals at a low concentration. These chaperone proteins also have another function beside delivery, which is to help maintain low levels of free concentration of these metals to prevent mismetallation and binding between other proteins that require MnII and FeII. Compartmentalization can overcome a protein's binding preference, as certain activities occur in different parts of the cell which have and require varying amounts of a metal. In cyanobacteria, it was found that MnII dependent perisplasmic protein must fold in the cytosol where MnII exists freely in a higher amount than ZuII, CuI, and CuII.

Techniques to Study RNR Activity[7]

[edit | edit source]There are several techniques used in the laboratory that are used to monitor the activity of the RNR metallocofactors. This contributes to identifying accurate proposed mechanism, generation, and function of these cofactors in vitro and in vivo by studying their movement.

- Whole-Cell Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: EPR was used in studying FeIIIFeIII-Y• biosynthesis in S. cerevisae. It was found that Y• levels were sufficiently high and detectable at endogenous levels in various growth conditions, meaning that the Y• is not modulated as a function of the cell cycle. A small molecule or protein factor must be needed to rapidly reduce the Y• in cell lysates, indicating the presence of a metallocofactor which was later identified to be iron.

- Mossbauer Spectroscopy: This type of spectroscopy monitors iron movement from oxidized and reduced iron pools into the RNR cofactor. It allows for the detection of all oxidation states of iron simultaneously and is sensitive to the surrounding electronic environments of the iron species present. In order for this technique to be accurate, cells first need to be labelled with the Fe57 isotope.

- ↑ Herrick J, Sclavi B. (2007) Ribonucleotide reductase and the regulation of DNA replication: an old story and an ancient heritage Mol Microbiol. 63:22–34

- ↑ Nordlund P, Reichard P (2006). Ribonucleotide Reductases Annu Rev Biochem, 75:681–706

- ↑ Cotruvo, Joseph, Jr., and Stubbe, JoAnne. (2011). Class I Ribonucleotide Reductases: Metallocofactor Assembly and Repair In Vitro and In Vivo Annual Review of Biochemistry, 80: 733-767

- ↑ Eklund H, Eriksson M, Uhlin U, Nordlund P, Logan D (1997). Ribonucleotide reductase--structural studies of a radical enzyme Biol Chem. 378:821–825

- ↑ Cotruvo, Joseph, Jr., and Stubbe, JoAnne. (2011). Class I Ribonucleotide Reductases: Metallocofactor Assembly and Repair In Vitro and In Vivo Annual Review of Biochemistry, 80: 733-767

- ↑ Cotruvo, Joseph, Jr., and Stubbe, JoAnne. (2011). Class I Ribonucleotide Reductases: Metallocofactor Assembly and Repair In Vitro and In Vivo Annual Review of Biochemistry, 80: 733-767

- ↑ Cotruvo, Joseph, Jr., and Stubbe, JoAnne. (2011). Class I Ribonucleotide Reductases: Metallocofactor Assembly and Repair In Vitro and In Vivo Annual Review of Biochemistry, 80: 733-767

Nucleotides

- Nucleotides consist of a base, sugar, and phosphate group. They are the building blocks of nucleic acids. Nucleotides are essential for the body for many reasons. They are needed for gene replication and transcription into RNA. They are also needed for energy. ATP, the body's form of energy, is a nucleotide with adenine as its base. Guanine nucleotides (GTP) are also a source of energy. Furthermore, derivatives of nucleotides are necessary in various biosynthetic processes. Nucleotides are necessary in signal transduction pathways as ewll.

The Biosynthesis of Nucleotides

There are two kinds of pathways in the biosynthesis of nucleotides: de novo and salvage. The following table contains similarities and differences between the two pathways.

| De Novo | Similarities | Salvage |

| Simpler compounds are used in the synthesis of nucleotides. Numerous small pathways are repeated to assemble different nucleotides. | Both synthesize nucleotides, though they utilize different mechanisms. | Bases are preformed, recovered, and reconnected to a ribose. |

| Synthesizes pyrimidine nucleotides. Bicarbonate, aspartate, and glutamine are used to synthesize the ring of the pyrimidine. The ring then links with ribose phosphate, forming the nucleotide. | Both assemble ribonucleotides, which are then used to synthezise deoxyribonucleotides for DNA. | Synthesizes purine nucleotides. Various precurosrs may be used to form the purine ring, which is then added to ribose and phosphate. |

- Feedback inhibition regulates multiple steps in the biosynthesis of nucleotides. Examples of this include activation and inactivation of aspartate transcarbamoylase in the synthesis of pyrimidines by CTP and ATP respectively, and activation and inactivation of glutamine-PRPP amidotransferase by purine nucelotides.

Reduction of Ribonucleotides to Deoxyribonucleotides

- Ribonucleotide reductase is a catalyst in reducing ribonucleoside diphosphates to deoxyribonucleotides. In this process, electrons flow from NADPH to sulfhydryl groups at ribonucleotide reductase's active sites. The reaction is summarized as follows:

- 1. An electron is transferred from cysteine on R1 to tyrosyl on R2. This creates a cysteine thiyl radical on R1, which is highly reactive on the active site.

- 2.A hydrogen from C3 of the ribose is then abstracted. This creates carbon radical.

- 3. The C3 radical helps release OH- at carbon-2. This departs as H2O after protonation from the second cysteine residue.

- 4. A third cysteine residue then provides a hydride to complete the reduction at C2. This returns the C3 to a radicala nd also generates a disulfide bond.

- 5. The c3 radical reacts with the original hydrogen that the first cysteine had extracted. A deoxyribonucleotide has now been generated and can leave the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase.

So What?

- The biosynthesis and metabolism of nucleotides are important to the body because disruptions in them can result in pathology. If nucleotides are not degraded properly, certain conditions may arise. An example of this is gout. Urates are degraded proteins, and gout is when they are accumulated, generating poor joints and arthritis.

- Similarly, if nucleotides are not synthesize properly, or if not enough are synthesized, conditions will arise as well. An example of this is the Lesch-Nyhan syndrome. Symptoms of this include mental deficiency, self-mutilation, and gout. This disease is due to a lack of an enzyme that is needed to synthesize purine nucleotides through the salvage pathway.

Source: Berg, Jeremy and Stryer, Lubert. Biochemistry: Fifth Edition. United States of America: W.H. Freeman and Company, 2002.

DNA and RNA Backbone

[edit | edit source]In macromolecules, such as DNA and RNA, there are linear polymers built and connected together by monomers. These monomers are known as nucleotides, and they consist of a nitrogenous base, a sugar, and a phosphate group. The chains and bonds between these nucleotides form the backbone of DNA and RNA, and these backbones allow the formation of unique genetic sequences. In DNA and RNA backbones, the monomers are connected by phosphodiester bridges. Specifically, the bridges are formed between the 3'-hydroxyl group of either the ribose sugar in RNA or deoxyribose sugar in DNA, and the 5'-hydroxyl group of the adjacent sugar; essentially called a 3'-5' phosphodiester bond. Chemically, to make this bond, the 3'-hydroxyl group of a sugar undergoes esterification with a phosphate group. That phosphate group then gets attacked by the 3'-hydroxyl group to form the phosphodiester bridge.

Once the phosphodiester bond is established, the backbone needs to be preserved in order to maintain the genetic information of the nucleotide sequence. Thus, no more nucleophilic attacks may occur on the backbone. In order to prevent nucleophilic attacks, the phosphate group on the phosphodiester bond has a negative charge which is used to prevent other nucleophilic species such as hydroxyl groups from attacking. The fact that DNA lacks a hydroxyl group on the 2' carbon means that it is more resistant to nucleophilic attacks, and thus, is the more stable hereditary material than RNA is.

Introduction

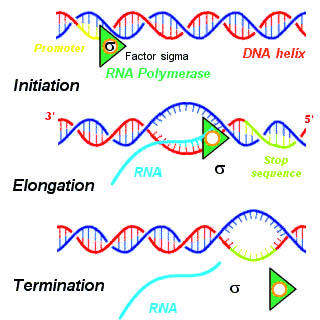

[edit | edit source]

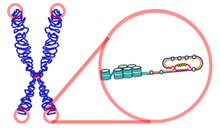

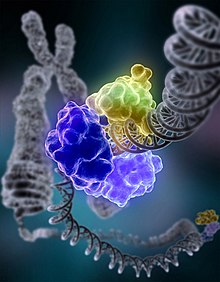

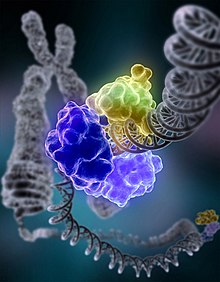

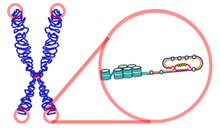

What is DNA? DNA is a long chain of linear polymers containing deoxyribose sugars and their covalently bonded bases known as nucleic acids. One of the major functions of the DNA is storage of the genetic information. In DNA a sequence of three bases, which is called a codon, is responsible for the encoding of a single amino acid. The amino acid is added to a growing protein during the process of translation. These nucleic acid polymers encode for the all of the materials an organism needs to live in the form of genes. Genes are small blocks of DNA that tell the cell which proteins it should create. The type of genes that a given cell receives depends entirely on the parent cells. Genes are passed on from generation to generation as a way of ensuring an organism's survival genetically.

DNA stands for deoxyribonucleic Acid. The prefix "deoxy" distinguishes DNA from its close relative RNA (ribonucleic acid). The prefix indicates that, unlike Ribose, Deoxyribose does not contain a hydroxyl group at the 2' carbon replacing it with a single Hydrogen atom. The absence of this Hydroxyl group is fundamental in determining the way in which DNA is able to condense itself within the nucleus of a cell.

DNA is a nucleic acid which is capable of duplicating itself via the enzyme known as DNA polymerase. Each of the four bases on DNA, Adenine (A), Cytosine (C), Guanine (G), and Thymine (T) is bonded covalently to a deoxyribose sugar. The four nucleotide units in DNA are called deoxyadenylate, deoxyguanylate, deoxycytidylate, and thymidylate. The nucleotide includes the nucleoside, a nitrogenous base bonded to a deoxyribose or ribose group. The four nucleosides in DNA are deoxyadenosine, deoxyguanosine, deoxycytidine, and thymide. By the joining one or more phosphate groups to a nucleoside through ester linkages, a nucleotide is formed.

The deoxyribose sugars form the structural backbone for DNA via a phosphodiester bond between the 3' carbon of one nucleotide and the 5' carbon of the next. When DNA is not self-replicating it exists in the cell as a double stranded helical molecule with the strands lined up anti-parallel to each other. That is to say if the orientation of one strand is 3' to 5' the other strand would be oriented 5' to 3'. The bases of each strand bind very specifically, A binds with T and C binds with G no other combination exists at least in DNA. The bases are bound to one another internally via hydrogen bonds with the phosphodiester bond backbone oriented to face outward. It is here that the missing 2' hydroxyl group plays an important role in DNA. It is the absence of this group that allows DNA to form its conventional double helix structure. RNA which does have a hydroxyl group at the 2' carbon is unable to obtain this same helical structure. The modern double helix structure of DNA was first proposed by Watson and Crick, and the functions of DNA were demonstrated in a series of experiments which will be discussed in the next few sections.

Why DNA? It is significant to note the reasons why DNA is the primary method through which all cells pass along genetic information. That is to say why has evolution favored a DNA world over an RNA world given that the two molecules are so similar structurally? These reasons involve chemical stability, energy needed to form and break chemical bonds, and the availability of enzymes to perform this task. The primary reason involves the relative stability of the two molecules. DNA is more chemically stable than RNA because it lacks the hydroxyl group on the 2' carbon. In RNA there are two possible OH groups that the molecule can form a phosphodiester bond between, which means that RNA is not forced into the same rigid structure as its deoxy counterpart. Additionally the deoxyribose sugar in DNA is much less reactive than the ribose sugar in RNA. Simply put C-H groups are significantly less reactive than C-OH (hydroxyl) groups. This difference also explains why RNA is not very stable in alkaline conditions, and DNA is. The base in alkaline condition does the same thing as the -OH group at the C2 position. Furthermore, double-strand DNA has relatively small grooves where damaging enzymes can't attach, making it more difficult for them to 'attack' the DNA. Double-stranded RNA, on the other hand, has much larger grooves, and therefore, it is more subject to being broken down by enzymes. The connection between the strands of double-stranded DNA is tighter than double-stranded RNA. In other words, it's much easier to unzip double-stranded RNA than it is to unzip double-stranded DNA. Overall, the breakdown and reform of RNA can be carried out faster and requires less energy than the breakdown and reform of DNA. It is essential to the organism's survival and well-being that its genetic material is encoded into something that is more stable and resistant to changes. In addition, the sequence of DNA and its physical conformation seems to play a part in DNA's selection as well. Another point that helps elucidate DNA's prevalence as the primary storage of genetic information is the availability of the enzyme that breaks down DNA. The body actively destroys foreign nucleases, which are enzymes that cleave DNA. This is only one of the many ways DNA is protected against damage. The body can actually recognize foreign DNA and destroy it, while leaving its own DNA intact.

Hyperchromic Effect Another unique feature of DNA in its double stranded form is the hyperchromic effect, which describes the decreasing absorbance of UV electromagnetic radiation of double helix strands as compared to the non-helical conformation of the molecule. The hydrogen bonding between complementary DNA strands as a result of sugar stacking in the helical conformation causes the aromatic rings to become increasingly stable and thus absorb less UV radiation. This ultimately decreases the amount of UV absorption by 40%. As the temperature is increased these hydrogen bonds dissolve and the helical structure begins to unwind. In this unwound form the aromatic rings are free to absorb much more UV radiation.

Properties of DNA

[edit | edit source]

1. Consists of 2 strands (anti-parallel and complementary): DNA has two polynucleotide chains that twist around a helical axis in opposite direction.

2. It is made up of deoxyribose sugar, a phosphate backbone on the exterior, and nucleic acid bases in the interior.

3. Bases are perpendicular to the helix axis that separated by 3.4 Angstroms.

4. Strands are held together by hydrogen bonds an other various intermolecular forces that form a double helix. The base pairing involves 2 hydrogen bonds for A - T and 3 hydrogen bonds for C - G -see in images to the right

5. Backbone consists of alternating sugars and phosphates, where phosphodiester linkages form the covalent backbone of the DNA.The direction of DNA goes from 5' phosphate group to 3' hydroxide group.

6. Repeats every 10 bases

7. Weak forces stabilize DNA because of the hydrophobic effects and VanDerWaals.

8. DNA chain is 20 Angstroms wide (2 nm)

9. One nucleotide unit is 3.3 Angstroms long (0.33 nm)

Primary Structure

[edit | edit source]DNA is made of two polynucleotide chains (strands) which run in opposite directions around the common axis. As a result, DNA has a double helical structure. Each polynucleotide chain of DNA consists of monomer units. A monomer unit consists of three main components that are a sugar, a phosphate, and a nitrogenous base. The sugar used in the DNA monomer unit is deoxyribose (it lacks an oxygen atom on the second Carbon in the furanose ring). There are also four possible nitrogen containing bases which can be used in the monomer unit of the DNA. Those bases are adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T). Adenine and guanine are purine derivatives, while cytosine and thymine are pyrimidine derivatives. Polymeric chain forms as a result of joining nucleosides (the sugar which is covalently bonded to the nitrogen containing base) through the phosphodiester linkage. Polymeric chain is a single strand of the DNA molecule. Two strands run in opposite directions to form double helix. The forces that keep those strands together are hydrogen bond, hydrophobic interactions, van de Waal force, and charge-charge interactions. The H-bonds form between base pairs of the antiparallel strands. The base in the first strand forms an H-bond only with a specific base in the second strand. Those two bases form a base-pair (H-bond interaction that keeps strands together and form double helical structure). The base –pairs are: adenine-thymine (A-T), cytosine-guanine (C-G). Such interaction gives us the hint that nitrogen-containing bases are located inside of the DNA double helical structure, while sugars and phosphates are located outside of the double helical structure. The hydrophobic bases are inside the double helix of DNA. The bases, located inside the double helix, are stacked one on the top of another. Stacking bases interact with each other through the Van der Waals force. Even though the van de Waal forces are week, sumation of those forces can be substantial. The distance between two neighboring bases that are perpendicular to the main axis is 3.4 A˚. DNA structure is repetitive. There are ten bases per turn, so every base has a 36° angle of rotation. The diameter of the double helix is approximately 20 A˚. The hydrophobic effect stabilizes the double helix. The structural variation in DNA is due to the different deoxyribose conformations, rotation about the contiguous bonds in the phosphodeoxyribose backbone, and free rotation about the C-1'- N (glycosyl bond).

The technique of southern blotting is often used to uncover the DNA sequence of a sample. The technique is named after Edwin Southern.

DNA Manipulation Techniques

[edit | edit source]When it comes to exploring genes and genomes, it depends on the technical tools that are used. The five important DNA manipulation techniques are:

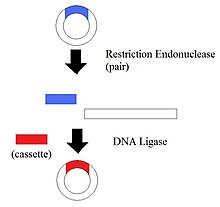

1.Restriction Endonucleases - also known as restriction enzymes

The restriction of enzymes split the DNA into specific fragments. By having the DNA split into different pieces, it allows the manipulation of DNA segments.

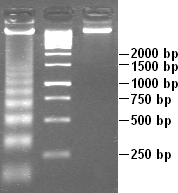

2. Blotting Technique

To separate and characterize DNA, the Southern blotting technique is used. This technique is similar to the Western blot, except that Southern blotting is used for DNA and not RNA. This technique identifies a specific sequence of DNA by electrophoresis through an agarose gel. The DNA is separated by placing the large fragments on top and the small fragments at the bottom. Next, the DNA is transfer into the nitrocellulose sheet. Then a 32-p labeled DNA probe that is complementary to the sequence, is added to hybridize the fragments. Finally, a autoradiography film is use to view the fragment containing the sequence.

3. DNA Sequencing

By using the DNA sequencing technique, a precise nucleotide sequence of a DNA molecule can be determined. The key to DNA sequencing is the generation of DNA fragments whose length depends on the last base of the sequence. Even though there are different alternative methods, they all perform the same procedure on the four reaction mixtures.

A. Chain termination DNA Sequencing

A primer is always needed. To produce fragments, the addition of 2', 3'-dideoxy analog of a dNTP is added to each of the four mixtures. It will stop the sequence at that N-dideoxy. The types of dNTP that can be use are dATP, TTP, dCTP, dGTP. In the end, new DNA strands are separated to electrophoresis.

B. Fluorescence Detection of Bases

Fluorescent tag is used into each of the four chain-terminating dideoxy nucleotides at different wavelengths. It is an effective method because no radioactive reagents are used and large sequences of bases can be determined. The fragments get separated by having the mixture passed through high voltage. Then, the fragments are detected by their fluorescence, which the base sequence is based on the color sequence.

C. Top-down (Shotgun) Method of Genome Sequencing

The top-down method and the shotgun method are similar, the main difference is that the top-down requires a detailed map of the clones. The Shotgun randomly sequences large clones to match them computationally.

D. Microarrays(Green chips)

Using microarrays is useful when it comes to studying the expression of a large number of genes. The microarray is created by using either oligonucleotides or cDNA. Based on the fluorescent intensity, red or green marks will appear. If it is red, it means no fluorescence is present, known as gene induction. If it is green, fluorescence is expressed, known as gene repression.

4. DNA Synthesis

To synthesize DNA, a solid-phase method is used. The solid-phase synthesis is carried out by the phosphite triester method. In this process only one nucleotide is added in each group. The first step that takes place is the binding of the first nucleotide. Another nucleotide is added and activated and reacts with the 3' -phosphoramididte containing DMT. A deoxyribonucleoside 3' -phosphoramidite with DMT and βCE is attached because it has the ability to synthesize any DNA. It is also a basic nucleotide that is modified and protected. Then, the molecule gets oxidized to oxidized the phosphate group. In the end, the DMT is removed by addition of dichloroacetic acid. Overall, the desired product remains insoluble and it is release at the end.

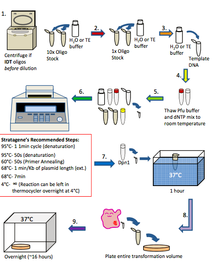

5. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

PCR is a technique used that allows to amplify DNA sequence between two nucleotides. If the DNA sequence is known, millions of copies of that sequence can be obtained by using this technique. To carried out PCR, a DNA template, a precursor, and two complementary primers are needed. What makes the PCR unique is that the temperature is constantly changing within the three different stages and that the stages get repeated 25 times. The three stages are:

1. Denaturing - DNA gets denature from a double strand (parent DNA molecule) to two single strands by heating thesolution at 94°C.

2. Annealing - After letting the solution cooled, two synthetic oligonucleotide primers are added at the end of the 3' end of target strand, and at the 3' end of complementary strand. This process is done when the temperature is between 50°C - 60°C.

3. Polymerization - Addition of thermostable DNA polymerase to catalyze 5' to 3' DNA synthesis at 72°C.

Structural Variation

[edit | edit source]Structural Variation occurs due to the different deoxyribose conformations, free rotation about the C-1, and rotation about the closest bond in phosphodeoxyribose backbones.

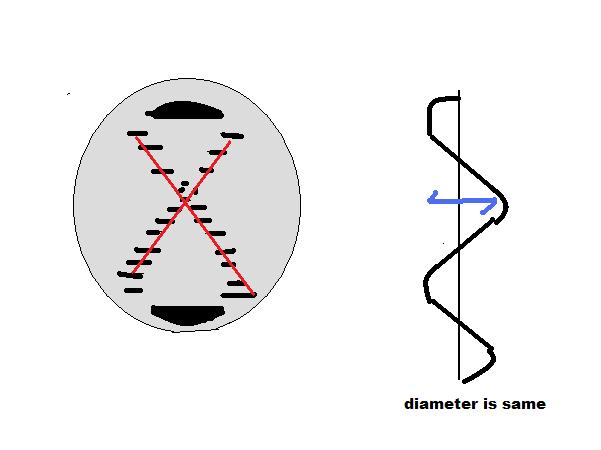

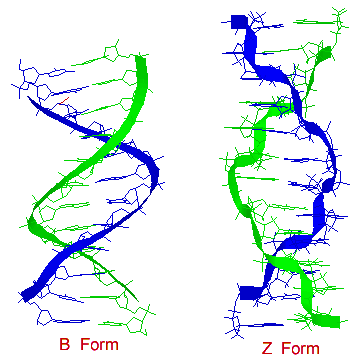

There are secondary structures when it comes to DNA which are forms A, B, and Z. A Form: 1. Right handed 2. Glycosyl bond conformation is ANTI 3. Needs 11 base pairs per helical turn 4. Size of diameter is about 26 angstroms 5. Sugar pucker conformation is at the C-3' endo.

B Form: 1. Like the A form, the B form is right handed. 2. Glycosyl bond formation is ANTI 3. Needs 10.5 base pairs per helical turn 4. Size of diameter is about 20 angstroms 5. Sugar pucker conformation is at the C-2' endo

Z Form: 1. Unlike the A and B form, the obvious difference is that the Z form is left handed. 2. Glycosyl bond formation consists of two components: pyrimidines and purines. ANTI (for pyrimidines) and SYN (for purines) 3. Needs 12 base pairs per helical turn 4. Size of diameter is about 18 angstroms 5. Sugar pucker conformation is at the C-2' endo (for pyrimidines) and C-3' endo (for purines)

DNA libraries

[edit | edit source]A DNA library is a collection of cloned DNA fragments in a cloning vector that can be searched for a DNA of interest. If the goal is to isolate particular gene sequences, two types of library are useful.

Genomic DNA libraries

[edit | edit source]A genomic DNA library is made from the genomic DNA of an organism. For example, a mouse genomic library could be made by digesting mouse nuclear DNA with a restriction nuclease to produce a large number of different DNA fragments but all with identical cohesive ends. The DNA fragments would then be ligated into linearized plasmid vector molecules or into a suitable virus vector. This library would contain all of the nuclear DNA sequences of the mouse and could be searched for any particular mouse gene of interest. Each clone in the library is called a genomic DNA clone. Not every genomic DNA clone would contain a complete gene since in many cases the restriction enzyme will have cut at least once within the gene. Thus some clones will contain only a part of a gene.

cDNA Library

[edit | edit source]A cDNA library is a library of mRNAs. It is made from introns and exons and a cDNA library is made to be able to isolate the genes/the final version of the gene.

A cDNA library i used to screen for colonies. If looking for a gene, you can screen the colonies, use the collection of plasmids, transform the bacteria, and use a probe. You can also use Southern Hybridization. By using an oligonucleotide that is complementary to the gene you are looking for, and that will eventually tell you which colonies of bacteria will have the DNA that corresponds with the mRNA in the plasmids.

How to make a cDNA library:

1. Isolate mRNA from the cell.

2. Use reverse transcriptase and dNTPss so that from the original mRNA, a DNA copy can be created.