US History/Print version

| This is the print version of US History You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Pre-Columbian America (before 1492)

- Brief overview of European history (before 1492)

- Vikings (1000-1013)

- Exploration (1492-1620)

- Early Colonial Period (1492 - 1607)

- The English Colonies (1607 - 1754)

- Road to Revolution (1754 - 1774)

- The American Revolution (1774 - 1783)

- A New Nation is Formed (1783 - 1787)

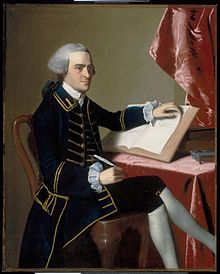

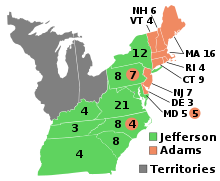

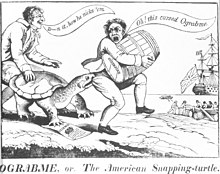

- The Early Years of the Constitutional Republic (1787 - 1800)

- Jeffersonian Republicanism (1800 - 1824)

- Panic of 1819

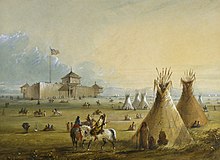

- Westward Expansion and Manifest Destiny (1824 - 1849)

- Friction Between the States (1849 - 1860)

- Intro to Secession

- Farewell to the Star-Spangled Banner (1860 - 1861)

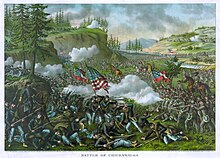

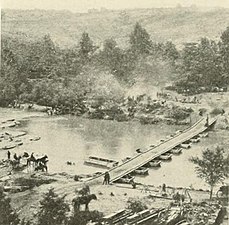

- The Civil War (1860 - 1865)

- Reconstruction (1865 - 1877)

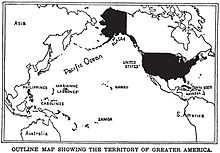

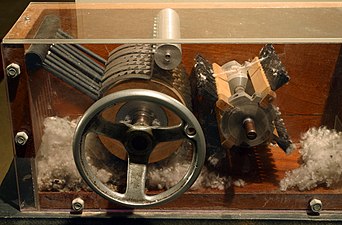

- The Age of Invention and the Gilded Age (1877 - 1900)

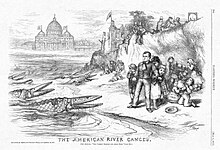

- The Progressive Era (1900 - 1914)

- World War I and the Treaty of Versailles (1914 - 1920)

- The Roaring Twenties and Prohibition (1920 - 1929)

- The Great Depression and the New Deal (1929 - 1939)

- Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

- World War II and the Rise of the Atomic Age (1939 - 1945)

- Truman and the Cold War (1945 - 1953)

- Eisenhower, Civil Rights, and the Fifties (1953 - 1961)

- Kennedy and Johnson (1961 - 1969)

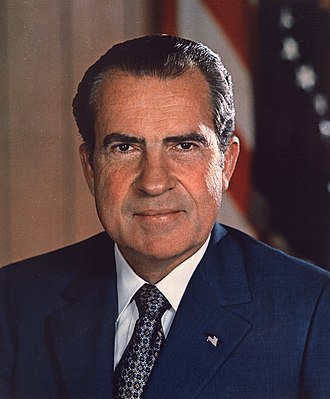

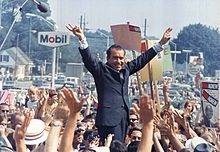

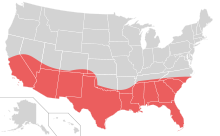

- Nixon presidency and Indochina (1969 - 1974)

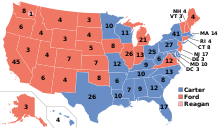

- Ford, Carter and Reagan presidencies (1974 - 1989)

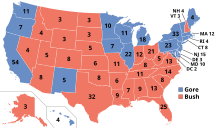

- Bush and Clinton presidencies,1st Gulf War (1989 - 2001)

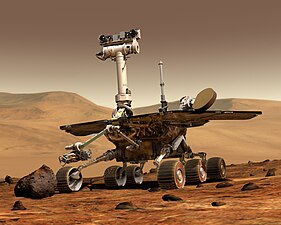

- George W. Bush, September 11, 2nd Gulf War, and Terrorism (2001-2006)

- Growing Crisis with Iran (2006-)

- 2008 Election

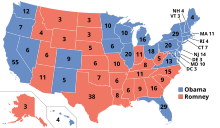

- Obama

- 2016 Election

- Trump

- Biden

- Hope

- Appendix Alpha: Presidents and Vice Presidents of the United States

- Appendix Beta: Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court

- Appendes Gamma: Supreme Court Decisions

- Appendex Delta: Famous Third Parties

Keywords (People, Events, etc)

Licensing and Contributors

Preface

This textbook is based on the College Entrance Examination Board test in Advanced Placement United States History. The test is a standard on the subject, covering what most students in the United States study in high school and college, so we treat it as the best reference.

The text was reorganized and edited in November 2008 to be closer to the content and organization the college board requires. The content was carefully chosen for significance and interest. We welcome reader feedback and suggestions for improvement.

Enjoy! The AP Course Description can be found here.

Colonial America

Introduction

Presentation

|

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the world's first open content US History Textbook. |

;

Content and Contributions

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the world's first open content US History Textbook. The users are invited to tweak and refine this book until there is nothing better available. The authors are confident that this will happen because of the success of the Wikipedia site.

Brief overview of European history (before 1492)

The peoples of Europe have had a tremendous effect on the development of the United States throughout the course of U.S. history. Europeans "discovered" and colonized the North American continent and, even after they lost political control over its territory, their influence has predominated due to a common language, social ideals, and culture. Therefore, when endeavoring to understand the history of the United States, it is helpful to briefly describe their European origin.

Greece and Rome

Ancient Greece

- See also: Ancient History/Greece

The first significant civilizations of Europe formed in the second millennium BCE. By 800 BCE, various Greek city-states, sharing a language and a culture based on slavery, pioneered novel political cultures. In the Greek city of Athens, by about 500 BCE, the male citizens who owned land began to elect their leaders. These elections by the minority of a minority represent the first democracy in the world. Other states in Greece experimented with other forms of rule, as in the totalitarian state of Sparta. These polities existed side by side, sometimes warring with each other, at one time combining against an invading army from Persia. Ancient Athens is known for its literary achievements in drama, history, and personal narrative. The individual city-states did not usually see themselves as a single entity. (The conqueror Alexander the Great, who called himself a Greek, actually was a native of the non-Greek state of Macedon.) The city-states of Greece became provinces of the Roman Empire in 27 BCE.

Rome

- See also: Ancient History/Rome

The city of Rome was founded (traditionally in the year 753 BCE). Slowly, Rome grew from a kingdom to a republic to a vast empire, which, at various points, included most of present-day Britain (a large part of Scotland never belonged to the empire), France (then known as Gaul), Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Iraq, Palestine (including the territory claimed today by the modern state of Israel), Northern Arabia, Egypt, the Balkans, and the entire north coast of Africa. This empire was maintained through free-born or adoptive citizenship, citizen education and indoctrination, a large and well-drilled army, and taxes directed by a large bureaucracy directed by the emperor. As each province produced more Roman citizens, the state became hard to maintain. Whole kingdoms in the north and east, and the invading peoples we know as the Germanic tribes (the Ostrogoths and Visigoths and the Franks) sat apart from the system.

After the death of one emperor in 180 CE, power struggles between the army and a succession of rulers of contested origins produced anarchy. Diocletian (243 - 316) reinstated the Empire by 284. Rome regained territory until 395, when the Empire was so large that it had to be divided into two parts, each with a separate ruler. The two halves sat uneasily together. The East, which considered itself the heir of Alexander the Great, spoke Greek or a dialect, while the West spoke Latin. The Eastern Empire survived until 1453, but the system to maintain the Western Empire broke apart. Plagues and crop failures troubled the world. In 476, Germanic tribes deposed the boy who was then the Emperor. Roman roads fell into disrepair, and travel became difficult. Some memories remained in the lands which had once known Roman rule. The supreme rulers of various tribes called themselves king, a distortion of the Roman word Caesar.

The Roman Empire to the Holy Roman Empire

After Rome's fall, monks from Ireland (which had never known Rome) spread Catholic Christianity and the culture and language of the Western Roman Empire across Europe. Catholicism eventually spread through England (where the Germanic tribes of the Angles and the Saxons now lived)and to the lands of the post-Roman Germanic tribes. Among those tribes, the Franks rose to prominence.

Charlemagne (742 - 814), the King of the Franks, conquered great portions of Europe. He eventually took control of Rome. The senate and the political organs of Rome had disappeared, and Charlemagne did not pretend to become the head of the Church. Charlemagne's domain, a confederation of what had been Roman Gaul with Germanic states, was much smaller than Diocletian had known. But prestige came with identity with the past, and so this trunk of lands became The Holy Roman Empire. Charlemagne's descendants, as well as local rulers, took their sanction from the Church, while the Church's pope influenced both religious and political matters.

The result of political stability was technological advance. After the year 1000, Western Europe caught some of the East's discoveries, and invented others. In addition to vellum, Europeans now started making paper of rags or wood pulp. They also adopted the wind and water mill, the horse collar (for plows and for heavy weights), the moldboard plow, and other agricultural and technological advances. Towns came into being, and then walled cities. More people survived, and the knights and kings over them grew restive.

Viking Exploration of North America

In the eighth century, pushed from their homes in Scandinavia by war and population expansion, Norsemen, or Vikings, began settling parts of the Faeroe, Shetland, and Orkney Islands in the North Atlantic. They went where ever treasure was, trading as far as Byzantium and Kiev in the East. In the West they raided from Ireland and England down to the Italian peninsula, sailing into a port, seizing its gold, and murdering or enslaving its people before fleeing. They began settling Iceland in approximately 874 CE. A Viking called Erik the Red was accused of murder and banished from his native Iceland in about 982. Eric explored and later founded a settlement in a snowy western island. Knowing that this bleak land would need many people to prosper, Eric returned to Iceland after his exile had passed and coined the word "Greenland" to appeal to the overpopulated and treeless settlement of Iceland. Eric returned to Greenland in 985 and established two colonies with a population of nearly 5000.

Leif Erikson, son of Erik the Red, and other members of his family began exploration of the North American coast in 986. He landed in three places, in the third establishing a small settlement called Vinland. The location of Vinland is uncertain, but an archeological site on the northern tip of Newfoundland, Canada (L'anse aux Meadows) has been identified as the site of a modest Viking settlement and is the oldest confirmed presence of Europeans in North America. The site contains the remains of eight Norse buildings, as well as a modern reproduction of a Norse longhouse. But the settlement in Vinland was abandoned in struggles between the Vikings and the native inhabitants, whom the settlers called Skraelingar. Bickering also broke out among the Norseman themselves. The settlement lasted less than two years. The Vikings would make brief excursions to North America for the next 200 years, though another attempt at colonization was soon thwarted.

By the thirteenth century, Iceland and Greenland had also entered a period of decline during the "Little Ice Age." Knowledge of their exploration, in the days before the printing press, was ignored in most of Europe. Yet the Vikings are now considered the true European discoverers of North America. The influence of their people outlasted even the terrible raids, and their grandchildren became kings and queens. For example, a branch of Viking descendants living in France, the Normans, conquered England from the Anglo-Saxons in 1066.

-

Danish seamen, painted mid-12th century.

-

A painting depicting Leif Erikson spotting land in North America.

-

A recreation of a viking village in Newfoundland.

The Great Famine and Black Death

The Little Ice Age led to European famines in the years 1315-1317 and in 1321. In the year 1318 sheep and cattle began to die of a contagious disease. Farmers could not support the growing population. And then, in 1347, some Genoese trading ships inadvertently brought a new, invasive species of rat to Europe. These rats carried bubonic plague.

Plague was also called the Black Death, from the darkened skin left after death and from its deadly reach. It had three strands: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic.[1] In bubonic plague fleas carried by the rats would leave their hosts and bite people. The masses of bacteria would flow through the human system, killing cells and leaving their refuse in lymph nodes in the armpit, groin, and neck. These nodes would swell and turn black, creating bubos. Infection could also spread into the lungs, so that a person might cough or sneeze the germ into the air. This created pneumonic plague, spreading disease into spaces where people gathered and where rats dared not go. It also spread through contamination of food. The last form of disease, and its most deadly, was septicemic. This attacked the blood, leaving stretches of pale skin looking black, and killing the person within hours.

Surviving laws of cities and guilds regulate public cleanliness and penalize adulteration of food. They cannot show how strictly these laws were applied. And they show no knowledge, of course, of germ theory and the need for sterilization. Older systems such as the few public baths which remained from the days of colonial Rome were seen as sinful and dangerous, invitations to the plague. The dwelling places of survivors of pre-Christian Rome, the Jews who were forced to live apart, were attacked by mobs who attributed the Black Death to their poisoning Christians' wells.

The responses to plague can be seen in the records left by survivors -- one third of the population of Europe died in repeated waves of disease -- and in the subsequent changes in society. Airplanes and satellites show the foundations of plague-era towns which were emptied by the disease. In just one square mile of pre-plague Europe there are reports of there being 50,000 people.[2] In large cities, families would flee or lock themselves away, trying to keep themselves from death. Other families were locked in by city authorities. This is the beginning of the modern system of quarantine.[3] Some branches of the family would not be among those so helped. The Black Death seemed erratic, sometimes taking people deemed good and pious, sometimes not. One priest or church prelate might die, and another survive. And a living priest might give no aid to other survivors. Some critiques of the Church which had become spread through most of Europe date from this era.

Although some lands became waste through lack of tilling, those people who survived grasped the property of those who had not. Europe then had a land-based economic system. Rich people became richer. There began a labor shortage: the farmers who survived needed hands to take in their crops. The wages of farm hands began to rise. In the surviving towns they needed people to guard the gates: in the courts they began to look for rising young men. Cities became more powerful in the depleted lands, and authority grew more centralized.

Education

During the Middle Ages Western society and education were heavily shaped by Christianity as expressed through the Roman Catholic Church. Towns, courts, and feudal manors had their priests, monasteries and nunneries had their scriptora or libraries, and after the 11th century CE, a few cities had Universities, schools to educate men to be high-ranking clerics, lawyers, or doctors. Where children had schools, their parents paid a fee so that they might learn Latin, the language St. Jerome had used for his translation of the Bible. Latin was the language of the Church. It was also learned, along with military tactics and the rules of chivalry, by men who trained to be knights. A smattering of Latin was necessary, along with Math, even for the elementary schools which sprang up in some cities. There both boys and girls were taught literacy and math, prerequisite for acceptance as an apprentice in many Guilds. Latin across Europe created a European-wide culture: a doctor from Padua could talk to his fellow from Oxford in Latin.

As in the Greek and Roman eras, only a minority of people went to school. There were not enough books, little travel, and no means of spreading standardized education. Schools were attended first by persons planning to enter religious life. Occasionally a cleric would reach out to educate a very bright peasant boy. This was one of the few ways peasants could rise in the world. But the vast majority of people were serfs who served as agricultural workers on the estates of feudal lords. They were, in effect, tied to the fate of the land. From the serf up to some high princes, the vast majority of people did not attend school, and were generally illiterate.

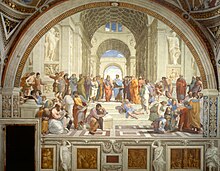

In the rise of the Universities in the 11th century, the Church translated several manuscripts of the ancient Greek writer Aristotle into Latin. From Aristotle's emphasis upon human reason, philosophy and science, and the Church's emphasis upon revelation and the teachings of Christ, medieval scholars developed Scholasticism. This was an philosophical and educational movement which attempted to integrate into an ordered system both the natural wisdom of Greece and Rome and the religious wisdom of Christianity. It was dominant in the medieval Christian schools and universities of Europe from about the middle of the 11th century to about the middle of the 15th century, though its influence continued in successive centuries. The idea of Man in the middle of ordered nature, and yet dominant over nature, bore fruit in the observation of natural phenomena, the beginnings of what the Western World knows as science. It also led to the exultation of system over observation, and the persistence of the Ptolemaic theories such as geocentrism among formally educated people.

Noble girls were sometimes sent to live in nunneries in order to receive basic schooling. Nuns would teach them to read and write and the chores necessary to run their establishments, including spinning and weaving. (Cloth-making was a major national industry in the Middle Ages.) They taught them their manners and their prayers. Some of these girls later became nuns themselves.

Christianity, Islam, Judaism

During the centuries after the fall of Rome, various flavors of Christian churches spread from Northern Africa and Armenia westward. This changed after Mohammed established Islam in 610 CE. Like Christianity, it spread through conversion and conflict. At its height it was also a faith of Europe, from Spain to Albania and Bosnia and their sister states. Both Prince and Caliph held that their state must have one faith, and no other belief was encouraged. When Jerusalem was reconquered by the Seljuq Turks, Christians were no longer able to go on religious pilgrimages to the Holy City.

At the end of the eleventh century, Pope Urban II inaugurated the Crusades, urging Western European kings and great nobles to begin what would be a century and a half of warfare. Christian armies fought first to reconquer and then to hold part of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Crusaders ultimately failed in the face of resurgent Muslim forces. Western Europeans within Church and State argued for and against the Crusades.

Despite the failure of the Crusades, militant Western Christianity persisted in Spain in an effort known as the Reconquista (the "reconquest"), which purged the land of the Muslims who had arrived there in 711. By the fifteenth century, the Muslims were confined to the kingdom of Granada, which bordered the Mediterranean Sea in the southern side of the Iberian Peninsula. Granada finally fell in 1492 to the Spanish Christians, ending the reconquista.

Rome had destroyed Israel in 70 CE, but allowed a remnant of her people to survive. Fortified by rabbinic culture and centered on the Torah, they became a resilient group. They survived as the known world became Christian. They spread, as traders, through East and West. However, Christian relationships with Jews were punctuated by hatred. They were held to be guilty of Jesus' death, and they were supposed to be evil because they had not converted to Christianity. They were forced into the notorious ghettos, usually built on waste or undesirable land. They were forced to wear strange clothing which marked them off, and to pay heavy taxes.[4] Christians spread rumors that Jewish officials sometimes kidnapped and killed young boys for their sacrifices. Sometimes a mob might break into the ghetto, killing some people. Individuals were sometimes forced to convert. One of the effects of European nationalism was the expulsion of a country's Jewish population. England was the first, in the 13th century; later, a reviving France; later still, Spain and Portugal. Some men crewing the ships in the Age of Exploration were Jews, often practicing their faith in hiding.

For a period in the late Twelfth century there two sets of Popes, a line in Rome and another in the French city of Avignon under the sway of that Court. In reaction against this, the Church centralized its powers in parallel to what nations were doing. There had been dissension before, in medieval England's Lollards and later with the Czech priest John Hus. However, it was only in an age after the printing press, when people began printing the Bible in their own languages, when Martin Luther founded the Protestant church. England's King Henry VIII, who had won the title "Protector of the Faith" for a work defending the Pope, later left it to become the head of the Church of England. This division of Western Christianity created religious minorities, who were persecuted throughout Europe. Among these were the Pilgrims, who helped settle America.

The Renaissance

- See also: European History

Another, more humble result of the plague was the accumulation of rags left over from clothing. These were quickly used to make paper. Books were very rare during the Middle Ages, and the monks who made them chained them to their shelves. It took one year for a man to make one book. In that climate Bibles took priority: we have only one copy of Democritus's most famous work surviving from this period. As rag paper replaced velum, books began to become more plentiful. The supply was augmented by Europe's adoption of Johannes Gutenberg 's fixed-type printing press in the 15th century.[5]

There had been earlier leaps in culture, including the wave of population and technological adaptation in the 12th century. This left its mark in increased population and the Roman Catholic Church's adoption of Aristotle. Yet the press made it possible for knowledge to have a foothold in society. Inventions in one place could be explained and adopted across a continent. The Greeks fleeing the fall of Byzantium brought their knowledge of ancient Greek culture to the West. The Bible, the basic book of Christendom, could be pored over by laypeople, and reading it could be learned by more people than ever before. Learning was no longer solely the province of the Church.

If the Bible was first off of the presses, pseudo-science and science followed soon after. The European witch trials were one result of the new medium. The questioning of scientific consensus was another. Andreas Vesalius published his observations about the circulatory system. Books discussing the theories of Nicolaus Copernicus and Galileo Galilei demolished the old geocentric theory of the cosmos. The arts were not neglected. Giorgio Vasari's biographical Lives introduced such new artists as Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti to the larger world.

A later time called this growth of knowledge the Renaissance. They said it began in the Italian city-states, spreading throughout most of Europe. The Italian city of Florence was called the birthplace of this intellectual movement.

Books spread the Crusader's newly found experience and knowledge of the Mediterranean, a region whose technology was at that time superior to that of western Europe. Books written about traders, adventurers, and scholars spread knowledge of Chinese technology such as gunpowder and silk. They spread writings of the ancient world which had been lost to Europe, and nurtured a taste for new foods and flavors. They spread pictures of ancient Greek statues, Moorish carpets, and strange practices.

In the fifteenth century, the Mediterranean was a vigorous trading area. European ships brought in grains and salts for preserving fish, Chinese silks, Indian cotton, precious stones, and above all, spices. White cane sugar could be used to preserve fruit and to flavor medicine. Cinnamon was medicine against bad humors as well as preservative and flavoring, part of the mysterious poudre douce, and now available even to some European common people.

Toward Nation-States

The great age of exploration was undertaken by nation-states, cohesive entities with big treasuries who tended to use colonization as a national necessity. When such nations as Portugal, England, Spain, and France became stronger, they began building ships.

The Rise of Portugal

The Italian peninsula dominated the world because of its position in the Mediterranean Sea. Universities in Padua, Rome, and elsewhere taught men from East and West. Above all, principalities such as the Republic of Venice and Florence controlled trade. Genoa and Venice in particular ballooned into massive trading cities. Yet there was at yet no nation of Italy, so each city's riches belonged only to that city. Individual cities used their monopoly to raise the price of goods, which would have been expensive in any case, because they were often brought overland from Asia to ports on the eastern Mediterranean. The mad prices, in turn, increased the desire of purchasers to find other suppliers, and of potential suppliers to find a better and cheaper route to Asia.

Portugal was just one of many potential suppliers, with a location which extended its influence into the Atlantic and down, south and east, to Africa. Prince Henry, son of King John I, promoted the exploration of new routes to the East. He planned Portugal's 1415 capture of Ceuta in Muslim North Africa. He also sponsored voyages that pushed even farther down the West African coast. By the time of his death in 1460, these voyages had reached south to Sierra Leone.

Under King John II, who ruled from 1481 to 1495, Bartolomeu Dias finally sailed around the southernmost point of Africa to the Cape of Good Hope (1487-1488). In 1497-1499 Vasco da Gama of Portugal sailed up the east coast of Africa to India.

The Portuguese colonized and settled such islands in the Atlantic as Madeira, Cape Verde, the Azores, and Sao Tome. These islands supplied them with sugar and gave them territorial control of the Atlantic. West Africa was more promising, not only unearthing a valuable trade route to India, but also providing the Portuguese with ivory, fur, oils, black pepper, gold dust, and a supply of dark skinned slaves who were used as domestic servants, artisans, and market or transportation workers in Lisbon. They were later used as laborers on sugar plantations on the Atlantic.

France, England, And The Hundred Years' War

King Harold of England faced William the Norman usurper after defeating the last Viking forces holding the North of England. And when William the Norman became William the Conqueror, he held England by consolidating the nation. His army was ruled from newly built castles, and had the best technology of the time. His sons and their sons fought the original inhabitants of their country in Scotland and Wales, pushing their boarders. They also claimed the right to their ancestral Normandy, in what is now France. (There had long been rivalry between England and France over the wool trade.) By a English king's marriage to an former queen of France, Eleanor of Aquitaine, the king subsequently claimed Aquitaine. During the years of 1337 to 1453, the kings of England claimed the whole of France and beyond, fighting The Hundred Years' War there and in the Low Countries. For some years the English threatened Paris, and there was a question whether the small area of France proper would be entirely conquered. The early stages of the war marked by English victory against a demoralized French people and their Prince. But around 1428, a young peasant girl from Lorriene, France named Joan of Arc approached a garrison of the French army. She told them that Saint Michael, Saint Catherine, and Saint Margaret had told her to lead the army to victory. She said that God had come to her in a dream, and told her how to defeat the English. She claimed that God said Prince Charles of France needed to be crowned in order for France to claim victory over the English.[6] After gaining the new French king, support of the populace, and several key victories, Joan was sold to the English for treason and as an appeasement. Yet France had been renewed. It pushed back against the invaders, and took back most of the land. In the next few centuries it was to remove England from Continental Europe.

The Hundred Years' War devastated both countries. But it ultimately turned both of them into stronger, colonial powers. The Hundred Years' War created opportunities for wealth and advancement for the knights of both countries. The Chivalric code showed great influence during this period. France absorbed Aquitaine, Castile, and Normandy itself, prosperous areas. The twin strokes of the plague and the Inquisition weakened opposition to the French king's rule. And English centralization continued as its own royalty sought service of serf and Baron. A group of new dialects, Middle English, came out of the tug between Norman lord and Anglo-Saxon peasant. If the nation could not get new land in Europe, it could use its ships to sail elsewhere.

Review Questions

1. Explain how one of these late medieval devices affected prosperity: the wind mill; the horse collar; the printing press.

2. How did the plague infect individuals? How did mass death affect society?

3. What was the importance of these four men to the Renaissance? Galileo Galilei, Nicolaus Copernicus, Andreas Vesalius, Leonardo Da Vinci.

References

- ↑ Massachusetts Medical Society, New England Surgical Society. Boston medical and surgical journal, Volume 149, Issue 2. 1903

- ↑ Gottfried, Robert S. The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe. Simon and Schuster, 1985. 64.

- ↑ Hunter, Susan S. Black death: AIDS in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. 115.

- ↑ (Charing pg. 18-23). Charing, Douglas. Judaism. New York, NY: DK Pub., 2003.

- ↑ Elizabeth Eisenstein, The printing press as an agent of change: communications and cultural transformations in early modern Europe (2 vols. ed.). Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. 1979. ISBN 0-521-22044-0

- ↑ Warner, Marina. Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism. University of California Press, 1999

Pre-Columbian America (before 1492)

Human civilization in the Americas probably began in the last ice age, when prehistoric hunters crossed a land bridge between the Asian and North American continents.[1] Civilizations in North America, Central America, and South America had different levels of complexity, technology, and cohesiveness.

Some of the most powerful and organized societies occurred in South and Central America. These cultures developed writing, allowing them to spread and dominate. They created some of the largest cities in the Ancient world.

North American cultures were more fragmented and less unified. The tribe was often the major social unit, with exchanges between tribes creating similar societies over vast distances. Tribal dwellings as large as European towns flourished in the rugged desert of southwestern North America.

European-descended historians have difficulty referring to these cultures as a whole, as the native people did not have a unified name for themselves. At first, Europeans called natives "Indians". This term came from the belief by Christopher Columbus that he had discovered a new passage to India.[2] Despite Amerigo Vespucci ascertaining that the Americas were not actually India, Indian continued to be used as the 'de facto' name for native inhabitants until around 1960.[2] Starting in the 1960s, the term "Native American" was used. Yet this term may be too problematic: The name America derives from Amerigo Vespucci, an Italian who had little to do with the native people.[2] There is also "American Indian". This is too general a term for a group having little in common other than skin tone and non-European language. In Canada, the term "First People" is used. All these terms for the native people of America show just how diverse Pre-Columbian America was and the disagreement continues among scholars today about this period.

Early Inhabitants of the Americas

Bering Land Bridge

American history does not begin with Columbus's 1492 arrival. The Americas were settled long before the first European arrived.[3] Civilization began during the last ice age, some 15 to 40 thousand years ago.[3] Huge ice sheets covered the north, so sea levels were much lower, creating a land bridge between Asia and North America.[3] This was the Bering land bridge, a gap in two large ice sheets creating a connection from lands near present day Alaska, through Alberta, and into the continental United States.[3]

Nomadic Asians following herds of wild game traveled into the continental United States. A characteristic arrow point was found and first described near the present day town of Clovis, NM. Specialized tools and common burial practices are seen in many archaeological sites through North America and into South America.

Clovis People

The Clovis people are one of North America's earliest civilizations. It is not clear if the finds represent one unified tribe, or many tribes with a common technology and belief. Their trek across 2000 rugged miles is one of the great feats of pre-history. Their culture disappears dramatically from the archaeological record 12,900 years ago, with widespread speculation about what caused their disappearance. Theories range from the extinction of the mammoth, to sudden environmental changes caused by a comet, to flooding caused by the break of a massive freshwater lake, Lake Agassiz.

There is controversy about Pre-Clovis settlement of North and South America. Comparisons of culture and linguistics offer evidence of the influence of early America by several different contemporary cultures. Some genetic and time-dating studies point to the possibility that ancient Americans came from other places and arrived earlier than at the Clovis sites in North America. Perhaps some ancient settlers to the hemisphere traveled by boat along the seashore, or arrived by boats from the Polynesian islands.

As time went on, many of these first settlers settled down into agricultural societies, complete with domesticated animals. Groups of people formed stable tribes and developed distinct languages of their own, to the point that more distant relatives could no longer understand them. Comparative linguistics -- the study of languages of different tribes -- shows fascinating diversity, with similarities between tribes hundreds of miles apart, yet startling differences with neighboring groups.

At times, tribes would gain regional importance and dominate large areas of America. Empires rose across the Americas that rivaled the greatest ones in Europe. For their time, some of these empires were highly advanced.

Early Empires of Mesoamerica

Meso-American civilizations are among of the most powerful and advanced civilizations of the ancient world. Reading and writing were widespread throughout Meso-America, and these civilizations achieved impressive political, artistic, scientific, agricultural, and architectural accomplishments. Many of these civilizations gathered the political and technological resources to build some of the largest, most ornate, and highly populated cities in the ancient world.

Maya

The aboriginal Americans settled in the Yucatan peninsulas of present-day Mexico around 10,000 BCE. By 2000 BCE, the Mayan culture had evolved into a complex civilization. The Mayans developed a strong political, artistic and religious identity among the highly populated Yucatan lowlands. The classic period (250-900 CE) witnessed a rapid growth of the Mayan culture and it gained dominance within the region and influence throughout present-day Mexico. Large, independent city-states were founded and became the political, religious, and cultural centers for the Mayan people.

Mayan society was unified not by politics, but by their complex and highly-developed religion. Mayan religion was astrologically based, and supported by careful observations of the sky. The Mayans had a strong grasp of astronomy that rivaled, and, in many ways, exceeded that of concurrent European societies. They developed a very sophisticated system for measuring time, and had a great awareness of the movements in the nighttime sky. Particular significance was attached to the planet Venus, which was particularly bright and appeared in both the late evening and early morning sky.

Mayan art is also considered one of the most sophisticated and beautiful of the ancient New World.

The Mayan culture saw a decline during the 8th and 9th century. Although its causes are still the subject of intense scientific speculation, archaeologists see a definite cessation of inscriptions and architectural construction. The Mayan culture continued as a regional power until its discovery by Spanish conquistadors. In fact, an independent, non-centralized government allowed the Mayans to strongly resist the Spanish conquest of present-day Mexico. Mayan culture is preserved today throughout the Yucatan, although many of the inscriptions have been lost.

Aztec

The Aztec culture began with the migration of the Mexica people to present-day central Mexico. The leaders of this group of people created an alliance with the dominant tribes forming the Aztec triple alliance, and created an empire that influenced much of present-day Mexico.

The Aztec confederacy began a campaign of conquest and assimilation. Outlying lands were inducted into the empire and became part of the complex Aztec society. Local leaders could gain prestige by adopting and adding to the culture of the Aztec civilization. The Aztecs, in turn, adopted cultural, artistic, and astronomical innovations from its conquered people.

The heart of Aztec power was economic unity. Conquered lands paid tribute to the capital city Tenochtitlan, the present-day site of Mexico City. Rich in tribute, this capital grew in influence, size, and population. When the Spanish arrived in 1521, it was the fourth largest city in the world (including the once independent city Tlatelolco, which was by then a residential suburb) with an estimated population of 212,500 people. It contained the massive Temple de Mayo (a twin-towered pyramid 197 feet tall), 45 public buildings, a palace, two zoos, a botanical garden, and many houses. Surrounding the city and floating on the shallow flats of Lake Texcoco were enormous chinampas -- floating garden beds that fed the many thousands of residents of Tenochtitlan.

While many Meso-American civilizations practiced human sacrifice, none performed it to the scale of the Aztecs. To the Aztecs, human sacrifice was a necessary appeasement to the gods. According to their own records, one of the largest slaughters ever performed happened when the great pyramid of Tenochtitlan was reconsecrated in 1487. The Aztecs reported that they had sacrificed 84,400 prisoners over the course of four days.

With their arrival at Tenochtitlan, the Spanish would be the downfall of Aztec culture. Although shocked and impressed by the scale of Tenochtitlan, the display of massive human sacrifice offended European sensitivity, and the abundant displays of gold and silver inflamed their greed. The Spanish killed the reigning ruler, Montezuma in June 1520 and lay siege to the city, destroying it in 1521, aided by their alliance with a competing tribe, the Tlaxcala.

Inca

With the ascension of Manco Capac to emperor of a tribe in the Cuzco area of what is modern-day Peru around 1200 BCE, the Incan civilization emerged as the largest Pre-Columbian empire in the Americas.

Religion was significant in Inca life. The royal family were believed to be descendants of the Inca Sun God. Thus, the emperor had absolute authority, checked only by tradition. Under the emperors, a complex political structure was apparent. The Incan emperor, regional and village leaders, and others were part of an enormous bureaucracy. For every ten people, there was, on average, one official. The organization of the Empire also included a complex transportation infrastructure. To communicate across the entire empire, runners ran from village to village, relaying royal messages.

In 1438, the ambitious Pachacuti, likely the greatest of the Incan emperors, came to the throne. Pachacuti rebuilt much of the capital city, Cuzco, and the Temple of the Sun. The success of Pachacuti was based upon his brilliant talent for military command (he is sometimes referred to as the "Napoleon of the Andes") and an amazing political campaign of integration. Leaders of regions that he wanted to conquer were bribed with luxury goods and enticed by promises of privilege and importance. As well, the Incans had developed a prestigious educational system which, not incidentally, just happened to extol the benefits of Incan civilization. Thus, much of the expansion throughout South America was peaceful.

At its height of power in the late 15th century, Incan civilization had conquered a vast patchwork of languages, people and cultures from present-day Ecuador, along the whole length of South America, to present-day Argentina.Cuzco, the capital city, was said by the Spanish to be "as fine as any city in Spain". Perhaps the most impressive city of the Incan empire, though, was not its capital, Cuzco, but the city Machu Picchu.

This mountain retreat was built high in the Andes and is sometimes called the "Lost City of the Incas." It was intended as a mountain retreat for the leaders of the Incan empire and demonstrates great artistry -- the abundant dry stone walls were entirely built without mortar, and the blocks were cut so carefully that one can't insert a knife-blade between them.

The Spanish discovered the Inca during a civil war of succession and enjoyed great military superiority over the slow siege warfare that the Incan empire had employed against its enemies. Fueled by greed at the opportunity to plunder another rich civilization, they conquered and executed the Incan emperor. The Incan empire fell quickly in 1533, but a small resistance force fled to the mountains, waging a guerrilla war of resistance for another 39 years.

Meso-American Empires

The Meso-American Empires were undoubtedly the most powerful and unified civilizations in the new world. Writings were common in Meso-America and allowed these cultures to spread in power and influence with far more ease than their counterparts in north America. Each of these civilizations built impressive urban areas and had a complex culture. They were as 'civilized' as the Spanish who conquered them in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Early Empires of the Southwest

Native Americans adapted the arid desert southwest. A period of relatively wet conditions saw many cultures in the area flourish. Extensive irrigation was developed that were among the biggest of the ancient world. Elaborate adobe and sandstone buildings were constructed. Highly ornamental and artistic pottery was created. The unusual weather conditions could not continue forever, though, and gave way, in time, to the more common drought of the area. These dry conditions necessitated a more minimal way of life and, eventually, the elaborate accomplishments of these cultures were abandoned.

Ancestral Puebloans

One prominent group were the Ancestral Puebloans, who lived in the present day Northeastern Arizona and surrounding areas. The geography of this area is that of a flat arid, desert plain, surrounded by small areas of high plateau, called mesas. Softer rock layers within the mesas eroded to form steep canyons and overhangs along their slopes.

The Ancestral Puebloans culture used these cave-like overhangs in the side of steep mesas as shelter from the brief, fierce southwestern storms. They also found natural seeps and diverted small streams of snow melt into small plots of maize, squash and beans. Small seasonal rivers formed beds of natural clays and dried mud. The Ancestral Puebloans used hardened dry mud, called adobe, along with sandstone, to form intricate buildings that were sometimes found high in the natural overhangs of the mesas. The Ancestral Puebloans were also skilled at forming the natural clays into pottery.

Between 900 - 1130 CE a period of relatively wet conditions allowed the Ancestral Puebloans to flourish. Traditional architecture was perfected, pottery became intricate and artistic, turkeys were domesticated, and trade over long distances influenced the entire region. Following this golden period was the 300 year drought called Great Drought. The Ancestral Puebloan culture was stressed and erupted into warfare. Scientists once believed the entire people vanished, possibly moving great distances to avoid the arid desert. New research suggests that the Ancestral Puebloans dispersed; abandoning the intricate buildings and moving towards smaller settlements to utilize the limited water that existed.

Hohokam

Bordering the Ancestral Puebloan culture in the north, a separate civilization emerged in southern Arizona, called the Hohokam. While many native Americans in the southwest used water irrigation on a limited scale, it was the Hohokam culture that perfected the technology (all without the benefit of modern powered excavating tools). The ability to divert water into small agricultural plots meant that the Hohokam could live in large agricultural communities of relatively high population density. This was particularly true in the Gila River valley, where the Gila River was diverted in many places to irrigate large fertile plains and numerous compact towns. The bigger towns had a 'Great House' at their centers, which was a large Adobe/stone structure. Some of these structures were four stories in size and probably were used by the managerial or religious elites. Smaller excavation or pits were enclosed by adobe walls and used as primary residences. Smaller pit rooms and pits were used for many different functions.

The successful use of irrigation is evident in the extensive Casa Grande village. Situated between two primary canals, the Casa Grande site has been the focus of nearly 9 decades of archaeological work. The original town was built around a Great House and incorporated open courtyards and circular plazas. By the 10th century neighboring settlements had been built to accommodate a large, highly developed region. The scale of this community can be seen in the results of one excavation of part of it in 1997. The project identified 247 pit houses, 27 pit rooms, 866 pits, 11 small canals, a ball court, and portions of four adobe walled compounds.

The Hohokam culture disintegrated when they had difficulty maintaining the canals in the dry conditions of the drought. Small blockages or collapses of the canal would choke the intricate irrigation networks. Large towns and extensive irrigation canals were abandoned. The people gave up their cultural way of life and dispersed into neighboring tribes.

Early Empires of the Mississippi

Native Americans in the Eastern Continental United States developed mound-building cultures early in North American History. Groups of native Americans became more stratified as time went on and developed into tribes. These tribes participated in long networks of trade and cultural exchanges. The importance of trade routes developed urban cities of great influence.

The mound-building people were one of the earliest civilizations to emerge in North America. Beginning around 1000 BCE cultures developed that used mounds for religious and burial purposes. These mound-building people are categorized by a series of cultures that describe distinctive artwork and artifacts found in large areas throughout the present-day eastern United States.

The burial mound was the principle characteristic of all of these societies. These large structures were built by piling baskets of carefully selected earth into a mound. Mounds were pyramid shaped with truncated tops. Sometimes small buildings were built on top of them. Some of these mounds were quite large. The Grave Creek Mound, in the panhandle of present day West Virginia, is nearly 70 feet tall and 300 feet in diameter. Other mounds have even been shown to be oriented in a way that allows for astronomical alignments such as solstices and equinoxes.

Mound building cultures spread out in size and importance. The first culture, the Adena, lived in present-day Southern Ohio and the surrounding areas. The succeeding cultures united to create an impressive trade system that allowed each culture to influence the other. The Hopewell exchange included groups of people throughout the continental Eastern United States. There began to be considerable social stratification within these people. This organization predates the emergence of the tribe as a socio-political group of people that would dominate later eastern and western native American civilization.

The climax of this civilization was the Mississippian culture. The mound-building cultures had progressed to social complexity comparable to Post-Roman, Pre-Consolidation Tribal England. Mounds became numerous and some settlements had large complexes of them. Structures were frequently built on top of the mounds. Institutional social inequalities existed, such as slavery and human sacrifice. Cahokia, near the important trade routes of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, became an influential and highly developed community. Extensive trade networks extended from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

Cahokia was one of the great centers of Mississippian culture and its largest settlement of Mississippi. The focal point of the settlement was the ceremonial mound called Monk's Mound. Monk's Mound was the largest mound ever constructed by mound-building people and was nearly 100 feet tall and 900 feet long. Excavation on the top of Monk's Mound has revealed evidence of a large building - perhaps a temple - that could be seen throughout the city. The city was spread out on a large plain south of Monks mound.

The city proper contained 120 mounds at varying distances from the city center. The mounds were divided into several different types, each of which may have had its own meaning and function. A circle of posts immediate to Monk's Mound marked a great variety of astronomical alignments. The city was surrounded by a series of watchtowers and occupied a diamond shape pattern that was nearly 5 miles across. At its best, the city may have contained as many as 40,000 people, making it the largest in North America.

It is likely the Mississippian culture was dispersed by the onslaught of viral diseases, such as smallpox, which were brought by European explorers. Urban areas were particularly vulnerable to these diseases, and Cahokia was abandoned in the 1500's. The dispersal of tribes made it impractical to build or maintain mounds and many were found abandoned by European explorers.

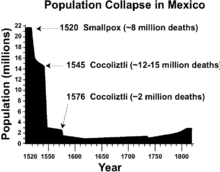

Contact with European Culture

Epidemics

European contact brought immediate changes in many tribes of North America. One of the most significant changes to all Indian tribes was the introduction of viral diseases and epidemics.[4][5] Smallpox was probably the single biggest scourge to hit North America. Infected contagious Indians spread the plague far inland almost immediately after early encounters with European settlers. It is estimated that around 90% of all Native Americans died from diseases soon after first contact.[6] The effects traumatized many powerful and important cultures. Urban areas were particularly vulnerable and Native American culture adapted by becoming more isolated, less unified, and with a renewed round of inter-tribal warfare as tribes seized the opportunity to gain resources once owned by rivals.

Columbian Exchange

On the other hand, Europeans brought invasive plants and animals.[7][8] The horse was re-introduced to America[9] (as original paleo-American populations of wild horses from the Bering land bridge were extinct) and quickly adapted to free range on the sprawling great plains. Tribes of nomadic Native Americans were quick to see the horse's value as an increase in their mobility;[10] allowing them to better adapt to changing conditions and as a valuable asset in warfare.[11] Along with Europeans bringing plants and animals, the Europeans were able to take several plants such as corn, potatoes, and tomatoes back to their native countries.[12]

Review Questions

1. Give two names for the indigenous peoples living in America, and name the circumstances behind each name.

2. What evidence do we have for the Inca, Mayan, and Aztec cultures?

3. What in the climate contributed to the rise and fall of the indigenous peoples of South-West North America?

References

- ↑ Gerszak, Fen Montaigne,Jennie Rothenberg Gritz,Rafal. "The Story of How Humans Came to the Americas Is Constantly Evolving" (in en). Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-humans-came-to-americas-180973739/.

- ↑ a b c "American Indians and Native Americans". www.umass.edu. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ↑ a b c d "Migration of Humans into the Americas (c. 14,000 BCE)". Climate Across Curriculum. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ↑ "Conclusion :: U.S. History". www.dhr.history.vt.edu. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ↑ "Columbian Exchange" (in en). Immigration History Research Center College of Liberal Arts. 16 June 2015. https://cla.umn.edu/ihrc/news-events/other/columbian-exchange.

- ↑ "Guns Germs & Steel: Variables. Smallpox PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ↑ "APWG: Background Information". cybercemetery.unt.edu. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ↑ "Escape of the invasives: Top six invasive plant species in the United States" (in en). Smithsonian Institution. https://www.si.edu/stories/escape-invasives.

- ↑ "History of Horses in America". www.belrea.edu. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ↑ "Wealth & Status A Song for the Horse Nation - October 29, 2011 through January 7, 2013 - The National Museum of the American Indian - Washington, D.C." americanindian.si.edu. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ↑ "Warfare A Song for the Horse Nation - October 29, 2011 through January 7, 2013 - The National Museum of the American Indian - Washington, D.C." americanindian.si.edu. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ↑ "Columbian Exchange (1492-1800)". Retrieved 26 December 2020.

Vikings (1000-1013)

Who were the Vikings?

The Norsemen (Norwegians) who lived around the beginning of the second millennium are today more commonly known as Vikings. The Vikings were farmers who "traded" during the slow months. Now, "trading" doesn't mean "I'll give you five sheep for that cow." It means "I'll give you five sheep for that cow. If you don't want to trade, I'll kill you." These people loved to travel in boats from one place to another, and this led to the second discovery of North America (Native Americans first, Vikings second, and Columbus third). Although Irish monks, most famously Brendan, and other European explorers had voyaged in the western waters, the Vikings established a settlement, the remains of which can be seen today at L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland.

Proported Ancestry and Descendants

The Norse are believed by some to have descended from the Huns, a people of uncertain ancestry. The Norse are believed by some to be the ancestors of the Goths and of modern Germans. There is no proof for these claims.

Eric "the Red" and his Children

Eric "the Red" fled Norway to Iceland to avoid facing a murder charge, and later was banished from Iceland for yet another murder. His children would have great impact on the discovery and explorations of North America.

Bjarni Ericson

Bjarni travelled around trading in his little knarr. A knarr is a small Norwegian boat that only fits about three to five people. Bjarni sighted Vinland (modern Newfoundland).

An interesting fact is that Leif Ericson bought Bjarni Herjólfsson's boat about ten years later, in about 995 C. E. This is the same boat in which Lief had discovered Vinland. Leif Ericson was about thirty years old (or thirty three, depending on whether one follows the "Eiríks saga rauða", i.e. the Saga of Eric the Red, or the "Grœnlendinga saga", or the Greenlanders Saga).

Thorvald Ericson

Explored from 1004 to 1005 AD.

Thorfinn Ericson

Traveled from 1008-1009 AD. He bravely took cattle with him on his knarr, hoping to settle in Greenland. "Greenland" is a misnomer, since it's covered in ice; his cattle died.

Freydis Erikidottir

Freydis was Eric's daughter, his fourth child. Since Freydis was a woman, there were many restrictions put upon her, but she wanted to make a name for herself. In 1013 AD, she explored with 2 Icelandic men, and killed them and their men upon arriving in Vinland (North America).

Leif Ericson

Leif Ericson did further exploration of Vinland and settled there. In 986, Norwegian-born Eirik Thorvaldsson, known as Eirik the Red, explored and colonized the southwestern part of Greenland. It was his son, Leiv Eiriksson, who became the first European to set foot on the shores of North America, and the first explorer of Norwegian extraction now accorded worldwide recognition.

The date and place of Leiv Eiriksson's birth has not been definitely established, but it is believed that he grew up on Greenland. The Saga of Eric the Red relates that he set sail for Norway in 999, served King Olav Trygvasson for a term, and was sent back to Greenland one year later to bring Christianity to its people.

Exploration (1266-1522)

Christopher Columbus

By the 15th Century European trade for luxuries such as spices and silk had inspired European explorers to seek new routes to Asia. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 had closed a crucial trade corridor. Trade throughout the Ottoman Empire was difficult and unreliable. Portugal was in the lead in exploration, slowly exploring the shores of the African Continent in search of a better route to the spices and luxuries of the Orient.

Then the Italian Christopher Columbus submitted plans for a voyage to Asia by sailing around the world. By the late 15th century most educated Europeans knew the world was round. The Greek mathematician Eratosthenes had accurately deduced that the world was approximately 25,000 miles in circumference. Many of the experts studying Columbus's plans on behalf of the European monarchies he approached for funding realized that this was too far for any contemporary sailing ship to go. Columbus contested the measurements, claiming that the world was much smaller than was widely believed.

After approaching the monarchies of several Italian city-states, and repeated appeals to the English and Portuguese monarchies, the Spanish King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella finally decided to give Columbus a chance. King Ferdinand thought Columbus might find something to compete with the neighboring kingdom of Portugal. Columbus set out on August 3rd, 1492. Five weeks later, after almost being thrown overboard by his own crew, the long voyage ended when land was sighted. This was an island called Guanahani (now known as San Salvador, in the island chain called the Bahamas). During this voyage Columbus also explored what is now considered the northeast coast of Cuba and the northern coast of Hispaniola. On his return to Spain, news of the new lands spread throughout Europe. Columbus was to make three more voyages to the New World between 1492 and 1503, exploring the Caribbean and the mainland of Central and South America. He imported sugar cane to the Americas, beginning an important industry.

Columbus was granted authority by the Spanish Monarchy to claim land for the Spanish, begin a settlement, trade for valuable goods or gold, and explore. He was also made governor of all the lands which he found. Columbus become an increasingly savage and brutal governor in the course of his four voyages. He enslaved and stole from the natives, at one point threatening to cut off the hands of any native who failed to give him gold. He was retired, and to the end of his life he believed that he had reached Asia.

It took another Italian explorer for Spain, Amerigo Vespucci, to correct this error. Amerigo described the lands around his islands and tried to deduce their proximity to Asia. From his voyages, Amerigo deduced that Columbus had found a new Continent. This new continent would be named America.

French Empire in North America

Christopher Columbus's voyages inspired other European powers to seek out the new world as well. Jacques Cartier, a respected mariner in his native France, proposed a trip to the North to investigate whether Asia could be reached from another route. His trip in 1534 retraced much of the voyages of the vikings and established contacts with natives in modern-day Canada. He explored some of northern Canada, established friendly relations with the American Indians, and discovered that the St Lawrence river region neither had abundant gold nor a northwest passage to Asia.

During the 16th century, the taming of Siberian wilderness by the Russians established a thriving fur trade which created a great demand for fur throughout Europe. France was quick to realize that the North held great potential as a provider of fur. Samuel de Champlain settled the first permanent settlement in present-day Canada and created a thriving trade with the Native Americans for beaver pelts and other animal hides.

Meanwhile, in the South, Early French Protestants, called Huguenots, had the opportunity to leave hostile European lands while advancing French claims to the new world. Settlements in present-day Florida and Georgia would create tension with Spanish conquistadors, who after conquering Caribbean lands would begin to expand their search for new lands. In contrast to these French Protestant colonies, in the 17th century French members of the Catholic order of Jesuits organized a settlement in what would become Maine, and began missionary efforts in what would become lower Canada and upper New York State.

Spanish Empire in North America

The Spanish conquistador Ponce de Leon was an early visitor to the Americas, traveling to the new world on Columbus's second voyage. He became the first governor of the present-day area of Puerto Rico in 1509. However, upon the death of Christopher Columbus, the Spanish did not allow Christopher's son to succeed. Like his father, he had committed atrocities against the Native Americans of the Caribbean. The two governors were released and replaced with successors from Spain.

Ponce De Leon, freed of his governorship, decided to explore areas to the north, where there was rumored to be a fountain of youth that restored the youth of anyone drinking from it. Ponce de Leon found a peninsula on the coast of North America, called the new land 'Florida' and chartered a colonizing expedition. His role was brief: attacked by Native American forces, he died in nearby Cuba.

By the early 16th century, Spanish conquistadors had penetrated deep into the Central and South American continents. Native American cultures had collected large troves of gold and valuables and given them to leaders of these prosperous empires. The conquistadors, believing they held considerable military and technological superiority over these cultures, attacked and destroyed the Aztecs in 1521 and the Incas in 1532.

The wealth seized by the Spanish would lead to piracy and a new wave of settlements as the other colonial powers became increasingly hostile towards Spain. Many areas that had been colonized by Spain were inundated with French and English pirates.

By 1565, Spanish forces looked to expand their influence to the New World by attacking the French settlement of Fort Caroline. The Spanish navy overwhelmed 200 French Huguenot settlers, slaughtering them even as they surrendered to Spain's superior military might. Spain formed the settlement of St. Augustine as an outpost to ensure that French Huguenots where no longer welcome in the area. St. Augustine is the oldest continuously occupied European-established city in North America.

In 1587 a Spanish Galleon landed in what is currently California with Filipinos aboard, making them among the first Asians to land in what would become the modern United States.[1]

Catholicism was introduced to the American colonies by the Spanish settlers in what is now present day Florida (1513) and the South West United States.[2] The first Christian worship service was a Catholic mass held in Florida in 1559, in what we now identify as Pensacola. Spain established the first permanent European Catholic settlement in St. Augustine, Florida in 1565, to help the settlers complete the "moral imperative" which was to convert all the Native peoples to Christianity, and to also to help support the treasure fleets of Spain.[3] During the time period of 1635-1675 Franciscans operated between 40 and 70 mission stations, attempting to convert about 26,000 "Hispanicized" natives who organized themselves into 4 provinces, Timucua, in central Florida, Guale, along the coast of Georgia, Apalachee on the northeastern edge of the Gulf of Mexico, and Apalachicola to the west.

British Empire in North America

England funded an initial exploratory trip shortly after Christopher Columbus's first voyage. Departing England in 1501, John Cabot explored the North American continent. He correctly supposed that the spherical shape of the earth made the North, where the longitudes are much shorter, a quicker route to the New World than a trip to the South islands Columbus was exploring. Encouraged, he asked the English monarchy for a more substantial expedition to further explore and settle the lands which he had found. The ships departed and were never seen again. England remained preoccupied with political affairs for much of the 16th century. This was despite the insistence of the author Richard Haklyt, who translated some of the accounts of exploration into English. He wrote that England ought to seek colonies in America, specifically in Virginia.

By the beginning of the 17th century, England, Scotland, and other English possessions had formed the nation of Great Britain and was becoming a formidable foe on the world's stage. The quickly expanding British navy was preparing for a massive strike upon the Spanish armada.

Sir Walter Raleigh, who had gained considerable favor from Queen Elizabeth I by suppressing rebellions in Ireland, sought to establish an empire in the new world. His Roanoke colony would be relatively isolated from existing settlements in North America. He funded the colony with his own money, unlike the previous explorers who had been funded and sponsored by monarchies. It is assumed that the colony was destroyed during a three year period in which England was at war with Spain and did serious damage to the Spanish navy.

The war left the British monarchy so drained of money and resources that the monarchy sold a charter containing lands between present-day South Carolina and the US-Canada border to two competing groups of investors, the Plymouth Company and the London Company. The two companies were given the North and South portions of this area, respectively. There was an overlapping area of development in the middle of the two Companies, a place both could exploit provided one Company's settlement wasn't within a hundred miles of the other's settlement. The Northern Plymouth settlement in Maine failed and was abandoned, but the London company established a Jamestown settlement in 1606.

Virginia and Jamestown

The new area was named Virginia, after both the organizing Virginia Company of London and Queen Elizabeth, "the Virgin Queen." Founded in 1607 with a charter from the Virginia Company, Jamestown was the first permanent English colony in the Americas. However, the swampy terrain was a breeding ground for mosquitoes, which carried dysentery, malaria, and smallpox, diseases that the English did not know. Many of the settlers fell sick and died shortly after.

In addition, Virginia's first government was weak, and its individuals frequently quarreled over policies. The colonists frantically searched for gold, silver, and gems, ignoring their own sicknesses. Indian raids further weakened defense and unification, and Jamestown began to die off. By the winter of 1609-1610, also known as the Starving Time, only 60 settlers remained from the original 500 passengers.

Two men helped the colony to survive: John Smith and John Rolfe. Smith, who arrived in Virginia in 1608, introduced an ultimatum: those who did not work would not receive food or pay. The colonists at last learned how to raise crops and trade with the nearby Indians, with whom Smith had made peace. In 1612, the English businessman Rolfe discovered that Virginia had ideal conditions for growing tobacco. This discovery, and the breeding of a new, "sweeter" strain, led to the plant becoming the colony's major cash crop. Tobacco was then used as medicine against the plague. With English demand for tobacco rising, Virginia had found a way to support itself economically.

In 1619, Virginia set up the House of Burgesses, the first elected legislative assembly in America. It marked the beginnings of self-government, replacing the martial law that was previously imposed on the colonists. However, at the same time Virginia was declared a "crown colony." Its charter was transferred from the Virginia Company to the Crown of England, which meant that Jamestown was now a colony run by the English monarchy. While the House of Burgesses was still allowed to run the government, the king also appointed a royal governor to settle disputes and enforce certain British policies.

Review Questions

1. Name the areas associated with these explorers: Christopher Columbus, Jacques Cartier, John Cabot, Sir Walter Raleigh.

2. Name three motives behind Columbus's voyages.

References

- ↑ https://migrationmemorials.trinity.duke.edu/items/landing-first-filipinos

- ↑ Death in Early America. Margaret M. Coffin. 1976

- ↑ American Catholics, James Hennesey, S.J. 1981

Early Colonial Period (1492 - 1607)

The Arrival of Columbus

Christopher Columbus and three ships - the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria - set sail on August 3, 1492. On October 12, a lookout cried out that he had sighted land. The crew set foot on an island that day, naming it San Salvador. It is unknown which exact island was discovered by Columbus. (Note that the island presently called San Salvador is so-called in honor of Columbus' discovery; it is not necessarily the one on which Columbus set foot.)

The Native Americans inhabiting the islands were described as "Indians" by Columbus, who had believed that he had discovered the East Indies (modern Indonesia). In reality, he had found an island in the Caribbean. He continued to explore the area, returning to Spain. Columbus' misconception that he found Asia was corrected years later by the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci, after whom America may be named.

The Protestant Reformation

In Europe, the power of the Pope and the influence of Catholicism was undoubted. The Catholic religion affected every aspect of politics on the continent. However, in the sixteenth century, the conditions were ripe for reform. Gutenberg's printing press made the spread of ideas much easier. The influence of nationalism grew, and rulers began to resent the power possessed by the Pope.

The Protestant movement may have commenced earlier, but the publication of Ninety-Five Theses by Martin Luther in 1517 spurred on the revolution within the Church. Luther attacked the Church's theology, which, he believed, misrepresented The Bible and placed too much authority in the hands of the clergy, and wished to reform the Church. After being excommunicated, Luther published many books on Reform. Luther's works were most influential in Germany and Scandinavia.

Persons other than Luther championed the cause of Reform. In Switzerland, Huldreich Zwingli advanced Protestant ideas, which mostly affected his home country. Similarly, Frenchman John Calvin helped the spread of Protestantism in France and the Netherlands.

English Protestantism resulted from the direct influence of the British monarch. Henry VIII (1509-1547) sought to divorce his wife, Catherine of Aragon, because she had failed to produce a viable male heir to the throne. When his divorce led to excommunication by the Pope, Henry simply declared the entire country free of Catholic domination and a bastion of Protestantism. Henry reasoned that England could survive under its own religious regulation (Anglican) and he named himself head of the church.

Elizabethan England

Elizabethan Succession

After Henry VIII died, he was succeeded by his son Edward VI (1547-1553) who reigned briefly before dying. Edward's death led to the ascension of Henry's daughter by Catherine, Mary I (1553-1558). A staunch Catholic, Mary sought to return England back to the Catholic church. Her religious zeal and persecution of Protestants earned her the nickname, "Bloody Mary." After a short reign, she was succeeded by her half-sister, Elizabeth. Elizabeth I (1558-1603) was the daughter of Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn. Her ascendency to the throne resulted when neither of her half siblings, Edward and Mary, produced an heir to the throne.

Religious Reform

Under her siblings' reign, the nation constantly battled religious fervor as it sought to identify itself as either Protestant or Catholic. Henry VIII had severed ties with the Roman Catholic Church upon his excommunication after divorcing Catherine of Aragon. He established the Church of England (the precursor to the Anglican Church) as the official state religion and named himself, not the Pope, as its head. Under Mary, the country returned to Catholic rule. The Elizabethan Age brought stability to English government. Elizabeth sought a compromise (the Elizabethan Settlement) which returned England to a nation governed by Protestant theology with a Catholic ritual. Elizabeth called Parliament in 1559 to consider the Reformation Bill that re-established an independent Church of England and redefined the sacrament of communion. Parliament also approved the Act of Supremacy, establishing ecclesiastical authority with the monarch.

Economic Reform

Elizabeth's far more important response was to stabilize the English economy following the 1551 collapse of the wool market. To respond to this economic crisis, Elizabeth used her power as monarch to shift the supply-demand curve. She expelled all non-English wool merchants from the empire. Her government placed quotas on the amount of wool that could be produced while also encouraging manors to return to agricultural production. She also started trading directly with the Spanish colonies in direct violation of their tariff regulations. This maritime violation would later result in an attack on England by the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Queen Elizabeth was a very popular monarch. Her people followed her in war and peace. She remained unmarried until her death, probably through a reluctance to share any power and preferring a series of suitors. This gave her the name, the Virgin Queen, and in honor of her, a colony was named Virginia a few years after her death.

In the aftermath of the Armada's overwhelming defeat and building on the development of a strong fleet started by Henry VIII, England began to gain recognition as a great naval power. Nationalism in England increased tremendously. Thoughts of becoming a colonial power were inspired. These thoughts were aided by the fact that the defeated Spanish lost both money and morale, and would be easy to oppose in the New World.

Early Colonial Ventures

Richard Hakluyt

In 1584, Richard Hakluyt proposed a strong argument for expansion of English settlement into the new world. With his Discourse Concerning Western Planting, Hakluyt argued that creating new world colonies would greatly benefit England. The colonies could easily produce raw materials that were unavailable in England. By establishing colonies, England would assure itself of a steady supply of materials that it currently purchased from other world powers. Second, inhabited colonies would provide a stable market for English manufactured goods. Finally, as the economic incentives were not enough, the colonies could provide a home for disavowed Englishmen.

Roanoke

The English had already begun the exploration of the New World prior to the Armada's defeat. In 1584, Queen Elizabeth granted Sir Walter Raleigh a charter authorizing him to explore the island of Roanoke, which is part of what is now North Carolina.

Between 1584 and 1586, Raleigh financed expeditions to explore the island of Roanoke and determine if the conditions were proper for settlement. In 1586, about a hundred men were left on the island. They struggled to survive, being reduced to eating dogs. They were, however, rescued- except for fifteen men whose fate remained a mystery.

After another expedition in 1587, another group of men, women, and children- a total of more than one-hundred people- remained on the island. Governor John White of the Roanoke colony discovered from a local Native American tribe that the fifteen men who were not rescued were killed by a rival tribe. While attempting to gain revenge, White's men killed members of a friendly tribe and not the members of the tribe that allegedly killed the fifteen men.

Having thus strained relations with the Natives, the settlers could not survive easily. John White decided to return to England in 1587 and return with more supplies. When he returned, England faced war against Spain. Thus delayed, White could not return to Roanoke until 1590. When he did return, White discovered that Roanoke was abandoned. All that gave clue to the fate of the colony was the word Croatan, the name of a nearby Native American tribe, carved out on to a tree. No attempt was made to discover the actual cause of the disappearance until several years later.

There are only theories as to the cause of the loss of Roanoke. There are two major possibilities. Firstly, the settlers may have been killed by the Natives. Second, the settlers may have assimilated themselves into the Native tribes. But there is no evidence that settles the matter beyond doubt.

Review Questions