US History/Constitution Early Years

Early Immigration to the Americas as of 1790

[edit | edit source]The following table is an approximation of the countries of origin for new arrivals to United States up to 1790.[1] The regions marked * were a part of Great Britain. The Irish in the 1790 census were probably mostly Irish Protestants and the French Huguenots. The total U.S. Catholic population in 1790 was probably less than 5%. [2]

| Group | Immigrants before 1790 | Population 1790 |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 360,000 (most as slaves) | 800,000 |

| England* | 230,000 | 1,900,000 |

| Ulster Scot-Irish* | 135,000 | 300,000 |

| Germany | 103,000 | 270,000 |

| Scotland* | 48,500 | 150,000 |

| Ireland* | 8,000 | (Incl. in Scot-Irish) |

| Netherlands | 6,000 | 100,000 |

| Wales* | 4,000 | 10,000 |

| France | 3,000 | 50,000 |

| Jews | 1,000 | 2,000 |

| Sweden | 500 | 2,000 |

| Other | --- | 200,000 |

James Webb, among others, has argued that not enough credit is given to early Scots-Irish for the role they played in early American history. These people formed a full 40% of the American Revolutionary army: their culture is now dominant in the American South, Midwest and Appalachian Region.

Failures Under Confederation

[edit | edit source]The original constitution as defined in the Articles of Confederation was meant to provide a league of sovereign states, rather than a united government. However, the uniting of these states in the Revolution showed flaws in this legislation. From place to place the same goods and services had a wide variation in price, and a wide variation in the way they were paid for. Should they be paid with trade in kind, as with many rural communities; in tobacco, as in Virginia; in gold and silver ores; or in Spanish Dollars or British Pound Sterling? If the last, how to establish that the states were neither Spanish nor British? Hard currency was in short supply following the American Revolution. The Revolution had been paid for in Continental specie: inflation left these bills "not worth a Continental." Several states had also printed paper currency, but it, like the Continental dollar, was heavily depreciated. Article Twelve said that War debts would be paid for by the central government, but Article Eight said that these monies would be raised by State legislatures. Without a strong central authority, how could equality of funding be assured? In fact, none of the debts, individual or national, had yet been paid, since the confederation had not the power of taxation. With all their rich resources, the States were running a trade deficit, buying many of their goods from the British. The confederation was also powerless to defend American navigational rights, evict the British from forts they were holding in violation of the Treaty of Paris, or settle disputes between two states.

The bankrupt confederation had trouble paying the soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War. This led to the Newburgh Conspiracy, an planned overthrow of the confederation which would have installed General Washington as head of a military junta. Washington, not interested in being a military dictator, quelled the cabal, negotiated pay and pensions for his soldiers[3], and resigned his commission, returning to civilian life at Mount Vernon.

One event that made it clear that some reform of the Articles was necessary was Shays' Rebellion. Thousands of disgruntled and impoverished farmer-soldiers, led by Daniel Shays, shut down courthouses and led an (ultimately unsuccessful) military uprising against the government of Massachusetts.

The Constitutional Convention

[edit | edit source]

In 1787, a Convention was called in Philadelphia with the declared purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation. However many delegates intended to use this convention for the purpose of drafting a new constitution. All states except for Rhode Island sent delegates, though all delegates did not attend. It was presided over by George Washington. Other leading figures at the convention included James Madison and John Randolph of Virginia, Ben Franklin, Gouverneur Morris and Robert Morris of Pennsylvania and Alexander Hamilton of New York. At the convention, the primary issue was representation of the states. Under the Articles, each state had one vote in Congress. The more populous states wanted representation to be based on population (proportional representation). James Madison of Virginia crafted the Virginia Plan, which guaranteed proportional representation and granted wide powers to the Congress. The small states, on the other hand, supported equal representation through William Paterson's New Jersey Plan. The New Jersey Plan also increased the Congress' power, but it did not go nearly as far as the Virginia Plan. The conflict threatened to end the Convention, but Roger Sherman of Connecticut proposed the "Great Compromise" (or Connecticut Compromise) under which one house of Congress would be based on proportional representation, while the other would be based on equal representation. Eventually, the Compromise was accepted and the Convention saved.

After settling on representation, compromises seemed easy for other issues. The question about the counting of slaves when determining the official population of a state was resolved by the Three-Fifths Compromise, which provided that slaves would count as three-fifths of persons. In another compromise, the Congress was empowered to ban the slave trade, but only after 1808. Similarly, issues relating to the empowerment and election of the President were resolved, leading to the Electoral College method for choosing the Chief Executive of the nation.

The Federalist Papers and Ratification

[edit | edit source]

The Convention required that the Constitution come into effect only after nine states ratify, or approve, it. The fight for ratification was difficult, but the Constitution eventually came into effect in 1788.

During 1788 and 1789, there were 85 essays published in several New York State newspapers, designed to convince New York and Virginia voters to ratify the Constitution. The three people who are generally acknowledged for writing these essays are Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay. Since Hamilton, Madison, and Jay were considered Federalists, this series of essays became known as "The Federalist Papers. One of the most famous Federalist Papers is Federalist No. 10, which was written by Madison and argues that the checks and balances in the Constitution prevent the government from falling victim to factions.

Anti-Federalists did not support ratification. Many individuals, such as Patrick Henry, George Mason, and Richard Henry Lee, were Anti-Federalists. The Anti-Federalists had several complaints with the constitution. One of their biggest was that the Constitution did not provide for a Bill of Rights protecting the people. They also thought the Constitution gave too much power to the federal government and too little to individual states. A third complaint of the Anti-Federalists was that Senators and the President were not directly elected by the people, and that the House of Representatives was elected every two years instead of annually.

On December 7, 1787, Delaware was the first state to ratify the Constitution. The vote was unanimous, 30-0. Pennsylvania followed on December 12 and New Jersey on ratified on December 18, also in a unanimous vote. By summer 1788, Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia and New York had ratified the Constitution, and it went into effect. On August 2, 1788, North Carolina refused to ratify the Constitution without amendments, but it relented and ratified it a year later.

A number of states that ratified the Constitution also issued statements requesting changes to the constitution, such as a Bill of Rights. This led to the Bill of Rights being drawn up in the first few years of the federal government.

The Bill of Rights

[edit | edit source]George Washington was inaugurated as the first United States president on April 30, 1789. However, North Carolina, Rhode Island and Vermont had not ratified the Constitution. Although governance was assured, there were no protections of people's religion, speech, or civil liberties. On September 26, 1789, Congress sent a list of twelve amendments to the states for ratification. Ten of the amendments would become the Bill of Rights. North Carolina ratified the Constitution in November of 1789, followed by Rhode Island in May 1790. Vermont became the last state to ratify the Constitution on January 10, 1791, becoming the 14th state in the Union.

The Bill of Rights was enacted on December 15, 1791. Here is a summary of the ten amendments ratified on that day:

- Establishes freedom of religion, speech, the press, assembly, petition.

- Establishes the right to keep and bear arms as part of a well-regulated militia.

- Bans the forced quartering of soldiers.

- Interdiction of unreasonable searches and seizures; a search warrant is required to search persons or property.

- Details the concepts of indictments, due process, self-incrimination, double jeopardy, rules for eminent domain.

- Establishes rights to a fair and speedy public trial, to a notice of accusations, to confront the accuser, to subpoenas, and to counsel.

- Provides for the right to trial by jury in civil cases

- Bans cruel and unusual punishment, and excessive fines or bail

- Lists unremunerated rights

- Limits the powers of the federal government to only those specifically granted by the constitution.

Washington Administration

[edit | edit source]

After George Washington had become the successful Commander in Chief of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War, he became the first President of the United States, holding office from 1789 to 1797. [4]

In 1788, the Electors unanimously chose Washington as president.[4] A short time after he had helped bring the government together, rivalries arose between his closest advisors, particularly between Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. Out of these developments evolved two new political parties: The Federalists, who shared the same name as the earlier pro-ratification party, and the Democratic-Republican Party, also known as the Jeffersonian party, or as the Anti-Federalists.

Washington's two-term administration set many policies and traditions that survive today. He was again unanimously elected in 1792. But after his second term expired, Washington again voluntarily relinquished power, thereby establishing an important precedent that was to serve as an example for the United States and also for other future republics.[4] Washington also abjured titles. He didn't want to be called "Your Excellency" or "Your Majesty." He insisted on being called "Mr. President," and referred to as "The President of the United States". Because of his central role in the founding of the United States, Washington is often called the "Father of his Country". Scholars rank him with Abraham Lincoln among the greatest of United States presidents.

Hamilton's Financial Plan

[edit | edit source]

One of the main conflicts between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists was over how to pay off Revolutionary War Debts. In 1790, Alexander Hamilton wrote his First Report on Public Credit to achieve this end. The report advocated that the federal government assume, or take over, state debts and turn them into one national debt. However, Jefferson and the anti-Federalists criticized this plan. In the Compromise of 1790, the federal government was allowed to assume state debts in exchange for the national capital being relocated to the District of Columbia.

In the Second Report on Public Credit, Hamilton argued that a National Bank was necessary to expand the flow of legal tender and encourage investment in the United States. Jefferson claimed that the creation of the National Bank violated the 10th Amendment of the Constitution, and therefore was unconstitutional. Hamilton responded that the bank was constitutional because the constitution gave "implied powers" to the Federal Government to do what was "necessary and proper" to fulfill its duties. Legislation creating the bank was passed in February 1791, and gave the bank a charter of twenty years.

Jefferson did not agree with Hamilton's idea of a national bank. Jefferson's faction envisioned an America more similar to ancient Athens or pre-Imperial Rome, with independent farming households following their own interests and nurturing liberty. Jefferson believed America should teach people to be self-sufficient farmers, and he wanted the federal government to stop interfering in state matters. (However, some evidence suggests Jefferson did support Hamilton's plan for paying off state debts. He wanted leverage to pressure Hamilton's agreement to locate the government's permanent capital in the South, on the Potomac River in what would become Washington, D.C.)

Both President Washington and Congress agreed to Hamilton's Bank. Jefferson's plan was overruled, and he eventually resigned as Secretary of State.

Whiskey Rebellion (1794)

[edit | edit source]

Washington was involved in one controversy during his presidency, the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794. The new Republic needed funds. This motivated Alexander Hamilton to press Congress to pass an excise tax on the sale of whiskey. Rural Pennsylvania farmers, who had never known a centralized American authority, were horrified by a call on what they considered their own profit and refused to pay the tax. A mob of 500 men attacked a tax collector's house. In response, Washington and Hamilton led an army of 15,000 men to quell the rebellion, an army larger than the force Washington had commanded in the American Revolution. When the army showed up, the rebels dispersed. The whiskey tax was eventually repealed by the Democratic Republicans in 1801.

Foreign Affairs

[edit | edit source]The French Revolution

[edit | edit source]The French Revolution broke out in 1789, a few months after the American Constitution had gone into effect. At first, as France overthrew the monarchy and declared itself a republic, many Americans supported the revolution. They believed their own revolt against England had spurred France to republicanism. But as the Reign of Terror began, and thousands of French aristocrats went to the guillotine, many Americans were shocked at the revolution's excesses. By the mid-1790s, as France went to war against neighboring monarchies, the revolution polarized American public opinion. Federalists viewed England, France's traditional enemy, as the bastion of stable government against a growing tide of French anarchy. Members of the emerging Democratic Republican Party, on the other hand, who took their party's name in part from the French Republic, believed the Terror to be a temporary excess and continued to view England as the true enemy of liberty.

President Washington's policy was neutrality. He knew that England, France, or even Spain, would be happy to eat up American resources and territory. The United States in the 1790s was still new and frail. He hoped that America could stay out of European conflicts until it was strong enough to withstand any serious foreign threat. Yet both England and France found opportunities to each use American resources against the other.

Hamilton and Jefferson clashed here as well. The former argued that the mutual defense treaty that the United States had signed with France in 1778 was no longer binding, as the French regime that had made that treaty no longer existed. The latter disagreed. But Washington sided with Hamilton, issuing a formal Proclamation of Neutrality in 1793. Washington repeated his belief in neutrality and argued against factionalism in his Farewell Address of 1796.

That same year, Citizen Edmund Charles Genêt arrived as the French minister to the United States. He soon began issuing commissions to captains of American ships who were willing to serve as privateers for France. This blatant disregard of American neutrality angered Washington, who demanded and got Genêt's recall.

English and Spanish Negotiations

[edit | edit source]The Royal Navy, meanwhile, began pressing sailors into service, including sailors on American merchant ships. Many English sailors had been lured into the American merchant service by high wages and comparatively good standards of living, and England needed these sailors to man its own fleet, on which England's national security depended. This violation of the American flag, however, infuriated Americans, as did the fact that England had not yet withdrawn its soldiers from posts in the Northwest Territory, as required by the Treaty of Paris of 1783.

In response, President Washington sent Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay to negotiate a treaty with England. But Jay had little leverage with which to negotiate: the final treaty did require immediate English evacuation of the frontier forts, but it said nothing about the matter of impressments. The Jay Treaty provoked an outcry among American citizens, and although the Senate ratified it narrowly, the debate it sparked was the final blow which solidified the Federalist and Republican factions into full-scale political parties, Federalists acquiescing in the treaty, and Republicans viewing it as a sell-out to England (and against France).

Spain, meanwhile, viewed the Jay Treaty negotiations with alarm, fearing that America and England might be moving towards an alliance. Without being certain of the treaty provisions, Spain decided to mollify the United States and give ground in the southwest before a future Anglo-American alliance could take New Orleans and Louisiana. Spain thus agreed to abandon all territorial claims north of Florida and east of the Mississippi, with the exception of New Orleans, and to grant the United States both the right to navigate the Mississippi and the right of commercial deposit in New Orleans. This would give westerners greater security and allow them to trade with the outside world. This Treaty of San Lorenzo, also called Pinckney's Treaty after American diplomat Charles Pinckney, was signed in 1795 and ratified the following year. Unlike Jay's treaty, it was quite popular.

If Jay's Treaty alarmed Spain, it angered France, which saw it as a violation of the Franco-American mutual defense treaty of 1778. By 1797, French privateers began attacking American merchant shipping in the Caribbean.

Election of 1796

[edit | edit source]

The first election where the presidency was not a foregone conclusion produced four candidates: Washington's Federalist Vice President John Adams, Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson, the Federalist Thomas Pinckney, and the Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr. (Burr was in fact hoping to become Vice President if the other Democratic-Republican were to win.) There were no Vice Presidential candidates, for under the original draft of the Constitution, the Vice President would be the candidate with the second-largest number of votes.

This was also the election testing the Constitution's Electoral College. Voters in each state did not directly elect candidates. Instead, their choices directed the two votes cast by the state's Electors.

In the election of 1796, John Adams won the required majority, but Thomas Jefferson came in second place. The President and the Vice President were in two different parties. The Constitutional role of the Vice President was defined in relation to the President: there was little else for him to do. Jefferson was isolated from an administration which supported strong government and a central Bank, and his contrary views were not consulted in the Adams administration.

The XYZ Affair

[edit | edit source]

Newly-elected President John Adams sent a delegation to Paris, resolving to negotiate a settlement with France. However, the delegates found it impossible even to secure an appointment with Talleyrand, the French foreign minister. The delegates were approached by three minor functionaries who insisted that the Americans pay a bribe to inaugurate negotiations, warning them of "the power and violence of France" if they refused. The delegates refused. ("The answer is no; no; not a sixpence," one of them retorted. This was popularly rendered as "Millions for defense, not a penny for tribute.") When Adams made the correspondence public, after replacing the names of the French functionaries with X, Y, and Z, American sentiment swung strongly against France. Under the control of the Federalists, Congress initiated a military buildup, fielding several excellent warships and calling Washington out of retirement to head the army. (Washington agreed only on condition that he not command until the army actually took the field. The army was never marshaled.)

The result was a Quasi-war, or an undeclared naval war with France. It consisted of combat between individual ships, mostly in the Caribbean, from 1798 to 1800. Eventually the United States and France agreed to end hostilities and to end the mutual defense treaty of 1778. Adams considered this one of his finest achievements.

Alien and Sedition Acts

[edit | edit source]Under Adams, the Federalist-dominated congress pushed passage of a series of laws under the cover of overcoming dangerous "aliens." In fact, the four acts were used to silence domestic political opponents.

- The Alien Act authorized the president to deport an alien deemed "dangerous."

- The Alien Enemies Act authorized the president to deport or imprison any alien from a country that the United States was fighting a declared war with.

- The Sedition Act made it a crime to criticize government officials and publish "false, scandalous, and malicious writing" against the government or its agents.

- The Naturalization Act changed the residency requirements for aliens to become citizens from 5 to 14 years.

Although it was openly deemed to be a security act, it provided powerful tools to the ruling Federalist party to quiet opposition from the growing Democratic-Republican Party. By extending the time required to become a citizen, they decreased the number of new voters that might choose to support the minority party. However, these acts were rarely enacted against political opponents due to the possibility of conflict such actions could create.

Education

[edit | edit source]In well-off families both boys and girls went to a form of infant school called a petty school. However only boys went to what you call grammar school. Upper class girls and sometimes boys were taught by tutors. Middle class girls might be taught by their mothers. Moreover during the 17th century boarding schools for girls were founded in many towns. In the boarding schools girls were taught subjects like writing, music and needlework. In the grammar schools conditions were hard. Boys started work at 6 or 7 in the morning and worked to 5 or 5.30 pm, with breaks for meals. Corporal punishment was usual. Normally the teacher hit naughty boys on the bare butt with birch twigs. Other boys in the class would hold the naughty boy down.

In the 17th and early 18th centuries women were not encouraged to get an education. Some people believed that if women were well educated it would ruin their marriage prospects and be harmful to their mind. Protestants believed that women as well as men should be able to read the bible. Only the daughters of the wealthy or nobility could get an education. By the mid 17th century young women were allowed to go to school with their brothers. Sometimes if you had the money you would be placed within a household of a friend and within the household and you would be taught various things. Some of the things you would learn would be to read and write, run a household, and practice surgery.

After the signing of the Declaration of Independence, several states had their own constitutions and there were sections in them that had information pertaining to education. But Thomas Jefferson had the thought that education should be left up to the government. He believed that education should not have a religious bias in it and believed that it should be free to all people not matter what their social status was. It was still very hard to make the concept of public schools easy for people to accept because of the vast number of people who were immigrating, the many different political views, and the different levels of economic difficulties.[5]

Technology

[edit | edit source]In the 1790s certain New England weavers began building large, automated looms, driven by water power. To house them they created the first American factories. Working the looms required less skill and more speed than household laborers could provide. The looms needed people brought to them; and they also required laborers who did not know the origin of the word sabotage. These factories sought out young women.

The factory owners said they wanted to hire these women just for a few years, with the ideal being that they could raise a dowry for their wedding. They were carefully supervised, with their time laid out for them. Some mill owners created evening classes to teach these women how to write and how to organize a household.

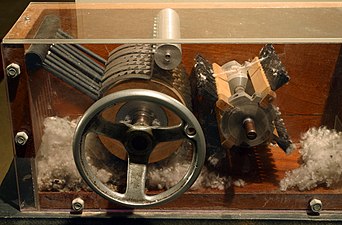

The factories provided a cheaper source of cotton cloth, sent out on ships and on roads improved by a stronger government. For the first time some people could afford more than two outfits, work and Sunday best. They also provided an outlet for cotton from the slave states in the South. Cotton was at that time one among many crops. Many slaves had to work to separate cotton from the seeds of the cotton plant, and to ship it to cloth-hungry New England. This was made simpler by Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin in 1793. Cotton became a profitable crop, and many Southern farms now made it their only crop. Growing and picking cotton was long, difficult labor, and the Southern plantation made it the work for slaves. Northern factories became part of the economy of slavery.

This renewed reliance on slavery was going against the trend in other parts of the country. Vermont had prohibited it in its state constitution in 1777. Pennsylvania passed laws for the gradual abolition of the condition in 1780, and New York State in 1799. Education, resources, and economic development created the beginnings of industrialization in many Northern states and plantations and slavery and less development in states in the Deep South.

-

Slater Mill, a historic textile mill built in 1793.

-

Reproduction of a Cotton Gin.

-

1798 portrait of an American Family. Advances in textiles made a difference in the world of clothing.

Review Questions

[edit | edit source]1. Identify, and explain the significance of the following people:

- (a) James Madison

- (b) William Paterson

- (c) Alexander Hamilton

- (d) Patrick Henry

- (e) Thomas Jefferson

- (f) George Washington

- (g) John Adams

- (h) Edmund Genet

- (i) Charles Pinckney

2. What was accomplished during the Constitutional Convention in terms of states' representations in the national government?

3. How did Hamilton take measures to ensure the ratification of the Constitution?

4. Name two problems or complaints the Anti-Federalists had with the Constitution.

5. What precedents did George Washington set in his two terms in office?

6. On what issues did Jefferson and Hamilton differ? How did this affect policies during the Washington administration?

7. What was the Whiskey Rebellion? Why was it significant?

8. What did Jay's Treaty and Pinckney's Treaty accomplish?

9. How did the United States respond to the French Revolution?

10. What was the XYZ Affair? What was its result?

11. What was the original purpose of the Alien, Sedition, and Naturalization Acts? How did their purpose change?

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Meyerink, Kory L., and Loretto Dennis Szucs. The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy.

- ↑ Meyerink and Szucs. The ancestry of the 3.9 million population in 1790 has been estimated by various sources by sampling last names in the 1790 census and assigning them a country of origin. This is an uncertain procedure, particularly in the similarity of some Scot-Irish, Irish, and English last names. None of these numbers are definitive and only "educated" guesses.

- ↑ https://npg.si.edu/blog/newburgh-conspiracy

- ↑ a b c https://www.si.edu/spotlight/highlights-george-washington-1732-1799

- ↑ A People and a Nation, Eighth Edition.