Sensory Systems/old/Biological Machines/Print version

| This is the print version of Biological Machines You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The Wikibook of

Biological Organisms, an Engineer's Point of View.

From Wikibooks: The Free Library

Preface

Table of Contents

Sensory Systems

Human Anatomy and Physiology

- Visual System

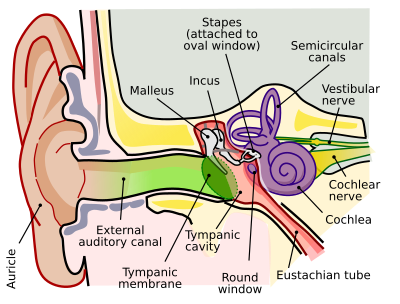

- Auditory System

- Vestibular System

- Somatosensory System

- Olfactory System

- Gustatory System

General Features

Technological Aspects

Other Animals

- Birds

- Fish

- Other Marine Animals (Octupus, Jellyfish, ...)

- Arthropods (Spiders, Insects, Ants, ...)

- Other Non-Primates (Rodents, Snakes, ...)

- Interspecies Comparison of the Visual System

Additional Information

Introduction

While the human brain may make us what we are, our sensory systems are our windows and doors to the world. In fact they are our ONLY windows and doors to the world. So when one of these systems fails, the corresponding part of our world is no longer accessible to us. Recent advances in engineering have made it possible to replace sensory systems by mechanical and electrical sensors, and to couple those sensors electronically to our nervous system. While to many this may sound futuristic and maybe even a bit scary, it can work magically. For the auditory system, so called “cochlea implants” have given thousands of patients who were completely deaf their hearing back, so that they can interact and communicate freely again with their family and friends. Many research groups are also exploring different approaches to retinal implants, in order to restore vision to the blind. And in 2010 the first patient has been implanted with a “vestibular implant”, to alleviate defects in his balance system.

The wikibook “Sensory Systems” wants to present our sensory systems from an engineering and information processing point of view. On the one hand, this provides some insight in the sometimes spectacular ingenuity and performance of our senses. On the other hand, it provides some understanding of how our senses transduce external information into signals that our central nervous system can work with, and how – and how well - this process can be replaced by technical components.

Sensory Systems

Biological Machines/Sensory Systems

Visual System

Introduction

Generally speaking, visual systems rely on electromagnetic (EM) waves to give an organism more information about its surroundings. This information could be regarding potential mates, dangers and sources of sustenance. Different organisms have different constituents that make up what is referred to as a visual system.

The complexity of eyes range from something as simple as an eye spot, which is nothing more than a collection of photosensitive cells, to a fully fledged camera eye. If an organism has different types of photosensitive cells, or cells sensitive to different wavelength ranges, the organism would theoretically be able to perceive colour or at the very least colour differences. Polarisation, another property of EM radiation, can be detected by some organisms, with insects and cephalopods having the highest accuracy.

Please note, in this text, the focus has been on using EM waves to see. Granted, some organisms have evolved alternative ways of obtaining sight or at the very least supplementing what they see with extra-sensory information. For example, whales or bats, which use echo-location. This may be seeing in some sense of the definition of the word, but it is not entirely correct. Additionally, vision and visual are words most often associated with EM waves in the visual wavelength range, which is normally defined as the same wavelength limits of human vision.

Since some organisms detect EM waves with frequencies below and above that of humans a better definition must be made. We therefore define the visual wavelength range as wavelengths of EM between 300nm and 800nm. This may seem arbitrary to some, but selecting the wrong limits would render parts of some bird's vision as non-vision. Also, with this range of wavelengths, we have defined for example the thermal-vision of certain organisms, like for example snakes as non-vision. Therefore snakes using their pit organs, which is sensitive to EM between 5000nm and 30,000nm (IR), do not "see", but somehow "feel" from afar. Even if blind specimens have been documented targeting and attacking particular body parts.

Firstly a brief description of different types of visual system sensory organs will be elaborated on, followed by a thorough explanation of the components in human vision, the signal processing of the visual pathway in humans and finished off with an example of the perceptional outcome due to these stages.

Sensory Organs

Vision, or the ability to see depends on visual system sensory organs or eyes. There are many different constructions of eyes, ranging in complexity depending on the requirements of the organism. The different constructions have different capabilities, are sensitive to different wave-lengths and have differing degrees of acuity, also they require different processing to make sense of the input and different numbers to work optimally. The ability to detect and decipher EM has proved to be a valuable asset to most forms of life, leading to an increased chance of survival for organisms that utilise it. In environments without sufficient light, or complete lack of it, lifeforms have no added advantage of vision, which ultimately has resulted in atrophy of visual sensory organs with subsequent increased reliance on other senses (e.g. some cave dwelling animals, bats etc.). Interestingly enough, it appears that visual sensory organs are tuned to the optical window, which is defined as the EM wavelengths (between 300nm and 1100nm) that pass through the atmosphere reaching to the ground. This is shown in the figure below. You may notice that there exists other "windows", an IR window, which explains to some extent the thermal-"vision" of snakes, and a radiofrequency (RF) window, of which no known lifeforms are able to detect.

Through time evolution has yielded many eye constructions, and some of them have evolved multiple times, yielding similarities for organisms that have similar niches. There is one underlying aspect that is essentially identical, regardless of species, or complexity of sensory organ type, the universal usage of light-sensitive proteins called opsins. Without focusing too much on the molecular basis though, the various constructions can be categorised into distinct groups:

- Spot Eyes

- Pit Eyes

- Pinhole Eyes

- Lens Eyes

- Refractive Cornea Eyes

- Reflector Eyes

- Compound Eyes

The least complicated configuration of eyes enable organisms to simply sense the ambient light, enabling the organism to know whether there is light or not. It is normally simply a collection of photosensitive cells in a cluster in the same spot, thus sometimes referred to as spot eyes, eye spot or stemma. By either adding more angular structures or recessing the spot eyes, an organisms gains access to directional information as well, which is a vital requirement for image formation. These so called pit eyes are by far the most common types of visual sensory organs, and can be found in over 95% of all known species.

Taking this approach to the obvious extreme leads to the pit becoming a cavernous structure, which increases the sharpness of the image, alas at a loss in intensity. In other words, there is a trade-off between intensity or brightness and sharpness. An example of this can be found in the Nautilus, species belonging to the family Nautilidae, organisms considered to be living fossils. They are the only known species that has this type of eye, referred to as the pinhole eye, and it is completely analogous to the pinhole camera or the camera obscura. In addition, like more advanced cameras, Nautili are able to adjust the size of the aperture thereby increasing or decreasing the resolution of the eye at a respective decrease or increase in image brightness. Like the camera, the way to alleviate the intensity/resolution trade-off problem is to include a lens, a structure that focuses the light unto a central area, which most often has a higher density of photo-sensors. By adjusting the shape of the lens and moving it around, and controlling the size of the aperture or pupil, organisms can adapt to different conditions and focus on particular regions of interest in any visual scene. The last upgrade to the various eye constructions already mentioned is the inclusion of a refractive cornea. Eyes with this structure have delegated two thirds of the total optic power of the eye to the high refractive index liquid inside the cornea, enabling very high resolution vision. Most land animals, including humans have eyes of this particular construct. Additionally, many variations of lens structure, lens number, photosensor density, fovea shape, fovea number, pupil shape etc. exists, always, to increase the chances of survival for the organism in question. These variations lead to a varied outward appearance of eyes, even with a single eye construction category. Demonstrating this point, a collection of photographs of animals with the same eye category (refractive cornea eyes) is shown below.

|

|

|

|

|

An alternative to the lens approach called reflector eyes can be found in for example mollusks. Instead of the conventional way of focusing light to a single point in the back of the eye using a lens or a system of lenses, these organisms have mirror like structures inside the chamber of the eye that reflects the light into a central portion, much like a parabola dish. Although there are no known examples of organisms with reflector eyes capable of image formation, at least one species of fish, the spookfish (Dolichopteryx longipes) uses them in combination with "normal" lensed eyes.

The last group of eyes, found in insects and crustaceans, is called compound eyes. These eyes consist of a number of functional sub-units called ommatidia, each consisting of a facet, or front surface, a transparent crystalline cone and photo-sensitive cells for detection. In addition each of the ommatidia are separated by pigment cells, ensuring the incoming light is as parallel as possible. The combination of the outputs of each of these ommatidia form a mosaic image, with a resolution proportional to the number of ommatidia units. For example, if humans had compound eyes, the eyes would have covered our entire faces to retain the same resolution. As a note, there are many types of compound eyes, but delving to deep into this topic is beyond the scope of this text.

Not only the type of eyes vary, but also the number of eyes. As you are well aware of, humans usually have two eyes, spiders on the other hand have a varying number of eyes, with most species having 8. Normally the spiders also have varying sizes of the different pairs of eyes and the differing sizes have different functions. For example, in jumping spiders 2 larger front facing eyes, give the spider excellent visual acuity, which is used mainly to target prey. 6 smaller eyes have much poorer resolution, but helps the spider to avoid potential dangers. Two photographs of the eyes of a jumping spider and the eyes of a wolf spider are shown to demonstrate the variability in the eye topologies of arachnids.

- Eye Topologies of Spiders

-

Wolf Spider

-

Jumping Spider

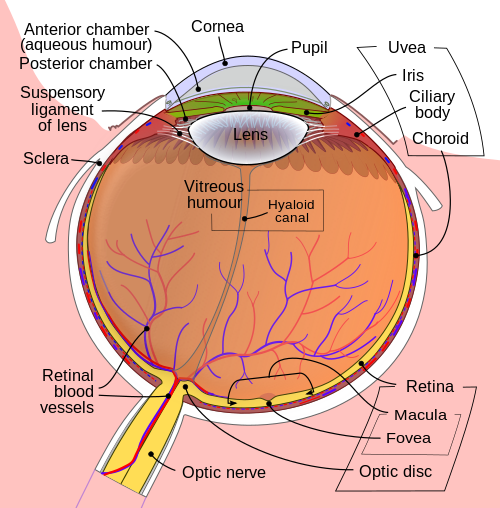

Anatomy of the Visual System

We humans are visual creatures, therefore our eyes are complicated with many components. In this chapter, an attempt is made to describe these components, thus giving some insight into the properties and functionality of human vision.

Getting inside of the eyeball - Pupil, iris and the lens

Light rays enter the eye structure through the black aperture or pupil in the front of the eye. The black appearance is due to the light being fully absorbed by the tissue inside the eye. Only through this pupil can light enter into the eye which means the amount of incoming light is effectively determined by the size of the pupil. A pigmented sphincter surrounding the pupil functions as the eye's aperture stop. It is the amount of pigment in this iris, that give rise to the various eye colours found in humans.

In addition to this layer of pigment, the iris has 2 layers of ciliary muscles. A circular muscle called the pupillary sphincter in one layer, that contracts to make the pupil smaller. The other layer has a smooth muscle called the pupillary dilator, which contracts to dilate the pupil. The combination of these muscles can thereby dilate/contract the pupil depending on the requirements or conditions of the person. The ciliary muscles are controlled by ciliary zonules, fibres that also change the shape of the lens and hold it in place.

The lens is situated immediately behind the pupil. Its shape and characteristics reveal a similar purpose to that of camera lenses, but they function in slightly different ways. The shape of the lens is adjusted by the pull of the ciliary zonules, which consequently changes the focal length. Together with the cornea, the lens can change the focus, which makes it a very important structure indeed, however only one third of the total optical power of the eye is due to the lens itself. It is also the eye's main filter. Lens fibres make up most of the material for the lense, which are long and thin cells void of most of the cell machinery to promote transparency. Together with water soluble proteins called crystallins, they increase the refractive index of the lens. The fibres also play part in the structure and shape of the lens itself.

Beamforming in the eye – Cornea and its protecting agent - Sclera

The cornea, responsible for the remaining 2/3 of the total optical power of the eye, covers the iris, pupil and lens. It focuses the rays that pass through the iris before they pass through the lens. The cornea is only 0.5mm thick and consists of 5 layers:

- Epithelium: A layer of epithelial tissue covering the surface of the cornea.

- Bowman's membrane: A thick protective layer composed of strong collagen fibres, that maintain the overall shape of the cornea.

- Stroma: A layer composed of parallel collagen fibrils. This layer makes up 90% of the cornea's thickness.

- Descemet's membrane and Endothelium: Are two layers adjusted to the anterior chamber of the eye filled with aqueous humor fluid produced by the ciliary body. This fluid moisturises the lens, cleans it and maintains the pressure in the eye ball. The chamber, positioned between cornea and iris, contains a trabecular meshwork body through which the fluid is drained out by Schlemm canal, through posterior chamber.

The surface of the cornea lies under two protective membranes, called the sclera and Tenon’s capsule. Both of these protective layers completely envelop the eyeball. The sclera is built from collagen and elastic fibres, which protect the eye from external damages, this layer also gives rise to the white of the eye. It is pierced by nerves and vessels with the largest hole reserved for the optic nerve. Moreover, it is covered by conjunctiva, which is a clear mucous membrane on the surface of the eyeball. This membrane also lines the inside of the eyelid. It works as a lubricant and, together with the lacrimal gland, it produces tears, that lubricate and protect the eye. The remaining protective layer, the eyelid, also functions to spread this lubricant around.

Moving the eyes – extra-ocular muscles

The eyeball is moved by a complicated muscle structure of extra-ocular muscles consisting of four rectus muscles – inferior, medial, lateral and superior and two oblique – inferior and superior. Positioning of these muscles is presented below, along with functions:

As you can see, the extra-ocular muscles (2,3,4,5,6,8) are attached to the sclera of the eyeball and originate in the annulus of Zinn, a fibrous tendon surrounding the optic nerve. A pulley system is created with the trochlea acting as a pulley and the superior oblique muscle as the rope, this is required to redirect the muscle force in the correct way. The remaining extra-ocular muscles have a direct path to the eye and therefore do not form these pulley systems. Using these extra-ocular muscles, the eye can rotate up, down, left, right and alternative movements are possible as a combination of these.

Other movements are also very important for us to be able to see. Vergence movements enable the proper function of binocular vision. Unconscious fast movements called saccades, are essential for people to keep an object in focus. The saccade is a sort of jittery movement performed when the eyes are scanning the visual field, in order to displace the point of fixation slightly. When you follow a moving object with your gaze, your eyes perform what is referred to as smooth pursuit. Additional involuntary movements called nystagmus are caused by signals from the vestibular system, together they make up the vestibulo-ocular reflexes.

The brain stem controls all of the movements of the eyes, with different areas responsible for different movements.

- Pons: Rapid horizontal movements, such as saccades or nystagmus

- Mesencephalon: Vertical and torsional movements

- Cerebellum: Fine tuning

- Edinger-Westphal nucleus: Vergence movements

Where the vision reception occurs – The retina

Before being transduced, incoming EM passes through the cornea, lens and the macula. These structures also act as filters to reduce unwanted EM, thereby protecting the eye from harmful radiation. The filtering response of each of these elements can be seen in the figure "Filtering of the light performed by cornea, lens and pigment epithelium". As one may observe, the cornea attenuates the lower wavelengths, leaving the higher wavelengths nearly untouched. The lens blocks around 25% of the EM below 400nm and more than 50% below 430nm. Finally, the pigment ephithelium, the last stage of filtering before the photo-reception, affects around 30% of the EM between 430nm and 500nm.

A part of the eye, which marks the transition from non-photosensitive region to photosensitive region, is called the ora serrata. The photosensitive region is referred to as the retina, which is the sensory structure in the back of the eye. The retina consists of multiple layers presented below with millions of photoreceptors called rods and cones, which capture the light rays and convert them into electrical impulses. Transmission of these impulses is nervously initiated by the ganglion cells and conducted through the optic nerve, the single route by which information leaves the eye.

A conceptual illustration of the structure of the retina is shown on the right. As we can see, there are five main cell types:

- photoreceptor cells

- horizontal cells

- bipolar cells

- amacrine cells

- ganglion cells

Photoreceptor cells can be further subdivided into two main types called rods and cones. Cones are much less numerous than rods in most parts of the retina, but there is an enormous aggregation of them in the macula, especially in its central part called the fovea. In this central region, each photo-sensitive cone is connected to one ganglion-cell. In addition, the cones in this region are slightly smaller than the average cone size, meaning you get more cones per area. Because of this ratio, and the high density of cones, this is where we have the highest visual acuity.

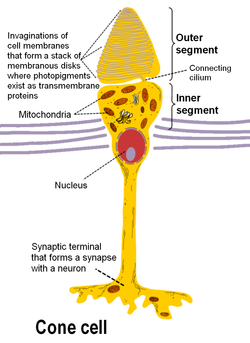

There are 3 types of human cones, each of the cones responding to a specific range of wavelengths, because of three types of a pigment called photopsin. Each pigment is sensitive to red, blue or green wavelength of light, so we have blue, green and red cones, also called S-, M- and L-cones for their sensitivity to short-, medium- and long-wavelength respectively. It consists of protein called opsin and a bound chromphore called the retinal. The main building blocks of the cone cell are the synaptic terminal, the inner and outer segments, the interior nucleus and the mitochondria.

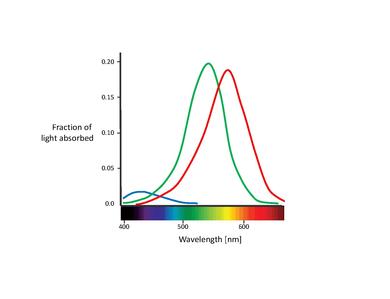

The spectral sensitivities of the 3 types of cones:

- 1. S-cones absorb short-wave light, i.e. blue-violet light. The maximum absorption wavelength for the S-cones is 420nm

- 2. M-cones absorb blue-green to yellow light. In this case The maximum absorption wavelength is 535nm

- 3. L-cones absorb yellow to red light. The maximum absorption wavelength is 565nm

The inner segment contains organelles and the cell's nucleus and organelles. The pigment is located in the outer segment, attached to the membrane as trans-membrane proteins within the invaginations of the cell-membrane that form the membranous disks, which are clearly visible in the figure displaying the basic structure of rod and cone cells. The disks maximize the reception area of the cells. The cone photoreceptors of many vertebrates contain spherical organelles called oil droplets, which are thought to constitute intra-ocular filters which may serve to increase contrast, reduce glare and lessen chromatic aberrations caused by the mitochondrial size gradient from the periphery to the centres.

Rods have a structure similar to cones, however they contain the pigment rhodopsin instead, which allows them to detect low-intensity light and makes them 100 times more sensitive than cones. Rhodopsin is the only pigment found in human rods, and it is found on the outer side of the pigment epithelium, which similarly to cones maximizes absorption area by employing a disk structure. Similarly to cones, the synaptic terminal of the cell joins it with a bipolar cell and the inner and outer segments are connected by cilium.

The pigment rhodopsin absorbs the light between 400-600nm, with a maximum absorption at around 500nm. This wavelength corresponds to greenish-blue light which means blue colours appear more intense in relation to red colours at night.

EM waves with wavelengths outside the range of 400 – 700 nm are not detected by either rods nor cones, which ultimately means they are not visible to human beings.

Horizontal cells occupy the inner nuclear layer of the retina. There are two types of horizontal cells and both types hyper-polarise in response to light i.e. they become more negative. Type A consists of a subtype called HII-H2 which interacts with predominantly S-cones. Type B cells have a subtype called HI-H1, which features a dendrite tree and an axon. The former contacts mostly M- and L-cone cells and the latter rod cells. Contacts with cones are made mainly by prohibitory synapses, while the cells themselves are joined into a network with gap junctions.

Bipolar cells spread single dendrites in the outer plexiform layer and the perikaryon, their cell bodies, are found in the inner nuclear layer. Dendrites interconnect exclusively with cones and rods and we differentiate between one rod bipolar cell and nine or ten cone bipolar cells. These cells branch with amacrine or ganglion cells in the inner plexiform layer using an axon. Rod bipolar cells connect to triad synapses or 18-70 rod cells. Their axons spread around the inner plexiform layer synaptic terminals, which contain ribbon synapses and contact a pair of cell processes in dyad synapses. They are connected to ganglion cells with AII amacrine cell links.

Amecrine cells can be found in the inner nuclear layer and in the ganglion cell layer of the retina. Occasionally they are found in the inner plexiform layer, where they work as signal modulators. They have been classified as narrow-field, small-field, medium-field or wide-field depending on their size. However, many classifications exist leading to over 40 different types of amecrine cells.

Ganglion cells are the final transmitters of visual signal from the retina to the brain. The most common ganglion cells in the retina is the midget ganglion cell and the parasol ganglion cell. The signal after having passed through all the retinal layers is passed on to these cells which are the final stage of the retinal processing chain. All the information is collected here forwarded to the retinal nerve fibres and optic nerves. The spot where the ganglion axons fuse to create an optic nerve is called the optic disc. This nerve is built mainly from the retinal ganglion axons and Portort cells. The majority of the axons transmit data to the lateral geniculate nucleus, which is a termination nexus for most parts of the nerve and which forwards the information to the visual cortex. Some ganglion cells also react to light, but because this response is slower than that of rods and cones, it is believed to be related to sensing ambient light levels and adjusting the biological clock.

Signal Processing

As mentioned before the retina is the main component in the eye, because it contains all the light sensitive cells. Without it, the eye would be comparable to a digital camera without the CCD (Charge Coupled Device) sensor. This part elaborates on how the retina perceives the light, how the optical signal is transmitted to the brain and how the brain processes the signal to form enough information for decision making.

Creation of the initial signals - Photosensor Function

Vision invariably starts with light hitting the photo-sensitive cells found in the retina. Light-absorbing visual pigments, a variety of enzymes and transmitters in retinal rods and cones will initiate the conversion from visible EM stimuli into electrical impulses, in a process known as photoelectric transduction. Using rods as an example, the incoming visible EM hits rhodopsin molecules, transmembrane molecules found in the rods' outer disk structure. Each rhodopsin molecule consists of a cluster of helices called opsin that envelop and surround 11-cis retinal, which is the part of the molecule that will change due to the energy from the incoming photons. In biological molecules, moieties, or parts of molecules that will cause conformational changes due to this energy is sometimes referred to as chromophores. 11-cis retinal straightens in response to the incoming energy, turning into retinal (all-trans retinal), which forces the opsin helices further apart, causing particular reactive sites to be uncovered. This "activated" rhodopsin molecule is sometimes referred to as Metarhodopsin II. From this point on, even if the visible light stimulation stops, the reaction will continue. The Metarhodopsin II can then react with roughly 100 molecules of a Gs protein called transducing, which then results in as and ß? after the GDP is converted into GTP. The activated as-GTP then binds to cGMP-phosphodiesterase(PDE), suppressing normal ion-exchange functions, which results in a low cytosol concentration of cation ions, and therefore a change in the polarisation of the cell.

The natural photoelectric transduction reaction has an amazing power of amplification. One single retinal rhodopsin molecule activated by a single quantum of light causes the hydrolysis of up to 106 cGMP molecules per second.

Photo Transduction

- A light photon interacts with the retinal in a photoreceptor. The retinal undergoes isomerisation, changing from the 11-cis to all-trans configuration.

- Retinal no longer fits into the opsin binding site.

- Opsin therefore undergoes a conformational change to metarhodopsin II.

- Metarhodopsin II is unstable and splits, yielding opsin and all-trans retinal.

- The opsin activates the regulatory protein transducin. This causes transducin to dissociate from its bound GDP, and bind GTP, then the alpha subunit of transducin dissociates from the beta and gamma subunits, with the GTP still bound to the alpha subunit.

- The alpha subunit-GTP complex activates phosphodiesterase.

- Phosphodiesterase breaks down cGMP to 5'-GMP. This lowers the concentration of cGMP and therefore the sodium channels close.

- Closure of the sodium channels causes hyperpolarization of the cell due to the ongoing potassium current.

- Hyperpolarization of the cell causes voltage-gated calcium channels to close.

- As the calcium level in the photoreceptor cell drops, the amount of the neurotransmitter glutamate that is released by the cell also drops. This is because calcium is required for the glutamate-containing vesicles to fuse with cell membrane and release their contents.

- A decrease in the amount of glutamate released by the photoreceptors causes depolarization of On center bipolar cells (rod and cone On bipolar cells) and hyperpolarization of cone Off bipolar cells.

Without visible EM stimulation, rod cells containing a cocktail of ions, proteins and other molecules, have membrane potential differences of around -40mV. Compared to other nerve cells, this is quite high (-65mV). In this state, the neurotransmitter glutamate is continuously released from the axon terminals and absorbed by the neighbouring bipolar cells. With incoming visble EM and the previously mentioned cascade reaction, the potential difference drops to -70mV. This hyper-polarisation of the cell causes a reduction in the amount of released glutamate, thereby affecting the activity of the bipolar cells, and subsequently the following steps in the visual pathway.

Similar processes exist in the cone-cells and in photosensitive ganglion cells, but make use of different opsins. Photopsin I through III (yellowish-green, green and blue-violet respectively) are found in the three different cone cells and melanopsin (blue) can be found in the photosensitive ganglion cells.

Processing Signals in the Retina

Different bipolar cells react differently to the changes in the released glutamate. The so called ON and OFF bipolar cells are used to form the direct signal flow from cones to bipolar cells. The ON bipolar cells will depolarise by visible EM stimulation and the corresponding ON ganglion cells will be activated. On the other hand the OFF bipolar cells are hyper polarised by the visible EM stimulation, and the OFF ganglion cells are inhibited. This is the basic pathway of the Direct signal flow. The Lateral signal flow will start from the rods, then go to the bipolar cells, the amacrine cells, and the OFF bipolar cells inhibited by the Rod-amacrine cells and the ON bipolar cells will stimulated via an electrical synapse, after all of the previous steps, the signal will arrive at the ON or OFF ganglion cells and the whole pathway of the Lateral signal flow is established.

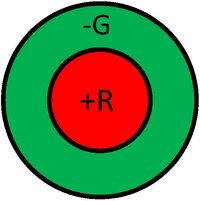

When the action potential (AP) in ON, ganglion cells will be triggered by the visible EM stimulus. The AP frequency will increase when the sensor potential increases. In other words, AP depends on the amplitude of the sensor's potential. The region of ganglion cells where the stimulatory and inhibitory effects influence the AP frequency is called receptive field (RF). Around the ganglion cells, the RF is usually composed of two regions: the central zone and the ring-like peripheral zone. They are distinguishable during visible EM adaptation. A visible EM stimulation on the centric zone could lead to AP frequency increase and the stimulation on the periphery zone will decrease the AP frequency. When the light source is turned off the excitation occurs. So the name of ON field (central field ON) refers to this kind of region. Of course the RF of the OFF ganglion cells act the opposite way and is therefore called "OFF field" (central field OFF). The RFs are organised by the horizontal cells. The impulse on the periphery region will be impulsed and transmitted to the central region, and there the so-called stimulus contrast is formed. This function will make the dark seem darker and the light brighter. If the whole RF is exposed to light. the impulse of the central region will predominate.

Signal Transmission to the Cortex

As mentioned previously, axons of the ganglion cells converge at the optic disk of the retina, forming the optic nerve. These fibres are positioned inside the bundle in a specific order. Fibres from the macular zone of the retina are in the central portion, and those from the temporal half of the retina take up the periphery part. A partial decussation or crossing occurs when these fibres are outside the eye cavity. The fibres from the nasal halves of each retina cross to the opposite halves and extend to the brain. Those from the temporal halves remain uncrossed. This partial crossover is called the optic chiasma, and the optic nerves past this point are called optic tracts, mainly to distinguish them from single-retinal nerves. The function of the partial crossover is to transmit the right-hand visual field produced by both eyes to the left-hand half of the brain only and vice versa. Therefore the information from the right half of the body, and the right visual field, is all transmitted to the left-hand part of the brain when reaches the posterior part of the fore-brain (diencephalon).

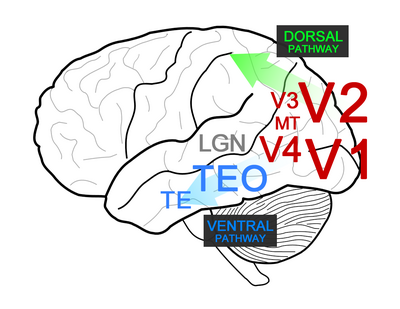

The information relay between the fibers of optic tracts and the nerve cells occurs in the lateral geniculate bodies, the central part of the visual signal processing, located in the thalamus of the brain. From here the information is passed to the nerve cells in the occipital cortex of the corresponding side of the brain. Connections from the retina to the brain can be separated into a 'parvocellular pathway' and a "magnocellular pathway". The parvocellular pathways signals color and fine detail, whereas the magnocellular pathways detect fast moving stimuli.

Signals from standard digital cameras correspond approximately to those of the parvocellular pathway. To simulate the responses of parvocellular pathways, researchers have been developing neuromorphic sensory systems, which try to mimic spike-based computation in neural systems. Thereby they use a scheme called "address-event representation" for the signal transmission in the neuromorphic electronic systems (Liu and Delbruck 2010 [1]).

Anatomically, the retinal Magno and Parvo ganglion cells respectively project to 2 ventral magnocellular layers and 4 dorsal parvocellular layers of the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus (LGN). Each of the six LGN layers receives inputs from either the ipsilateral or contralateral eye, i.e., the ganglion cells of the left eye cross over and project to layer 1, 4 and 6 of the right LGN, and the right eye ganglion cells project (uncrossed) to its layer 2, 3 and 5. From here the information from the right and left eye is separated.

Although human vision is combined by two halves of the retina and the signal is processed by the opposite cerebral hemispheres, the visual field is considered as a smooth and complete unit. Hence the two visual cortical areas are thought of as being intimately connected. This connection, called corpus callosum is made of neurons, axons and dendrites. Because the dendrites make synaptic connections to the related points of the hemispheres, electric simulation of every point on one hemisphere indicates simulation of the interconnected point on the other hemisphere. The only exception to this rule is the primary visual cortex.

The synapses are made by the optic tract in the respective layers of the lateral geniculate body. Then these axons of these third-order nerve cells are passed up to the calcarine fissure in each occipital lobe of the cerebral cortex. Because bands of the white fibres and axons pair from the nerve cells in the retina go through it, it is called the striate cortex, which incidentally is our primary visual cortex, sometimes known as V1. At this point, impulses from the separate eyes converge to common cortical neurons, which then enables complete input from both eyes in one region to be used for perception and comprehension. Pattern recognition is a very important function of this particular part of the brain, with lesions causing problems with visual recognition or blindsight.

Based on the ordered manner in which the optic tract fibres pass information to the lateral geniculate bodies and after that pass in to the striate area, if one single point stimulation on the retina was found, the response which produced electrically in both lateral geniculate body and the striate cortex will be found at a small region on the particular retinal spot. This is an obvious point-to-point way of signal processing. And if the whole retina is stimulated, the responses will occur on both lateral geniculate bodies and the striate cortex gray matter area. It is possible to map this brain region to the retinal fields, or more usually the visual fields.

Any further steps in this pathway is beyond the scope of this book. Rest assured that, many further levels and centres exist, focusing on particular specific tasks, like for example colour, orientations, spatial frequencies, emotions etc.

Information Processing in the Visual System

Equipped with a firmer understanding of some of the more important concepts of the signal processing in the visual system, comprehension or perception of the processed sensory information is the last important piece in the puzzle. Visual perception is the process of translating information received by the eyes into an understanding of the external state of things. It makes us aware of the world around us and allows us to understand it better. Based on visual perception we learn patterns which we then apply later in life and we make decisions based on this and the obtained information. In other words, our survival depends on perception. The field of Visual Perception has been divided into different subfields, due to the fact that processing is too complex and requires of different specialized mechanisms to perceive what is seen. These subfields include: Color Perception, Motion Perception, Depth Perception, and Face Recognition, etc.

Deep Hierarchies in the Primate Visual Cortex

Despite the ever-increasing computational power of electronic systems, there are still many tasks where animals and humans are vastly superior to computers – one of them being the perception and contextualization of information. The classical computer, either the one in your phone or a supercomputer taking up the whole room, is in essence a number-cruncher. It can perform an incredible amount of calculations in a miniscule amount of time. What it lacks is creating abstractions of the information it is working with. If you attach a camera to your computer, the picture it “perceives” is just a grid of pixels, a 2-dimensional array of numbers. A human would immediately recognize the geometry of the scene, the objects in the picture, and maybe even the context of what’s going on. This ability of ours is provided by dedicated biological machinery – the visual system of the brain. It processes everything we see in a hierarchical way, starting from simpler features of the image to more complex ones all the way to classification of objects into categories. Hence the visual system is said to have a deep hierarchy. The deep hierarchy of the primate visual system has inspired computer scientists to create models of artificial neural networks that would also feature several layers where each of them creates higher generalizations of the input data.

Approximately half of the human neocortex is dedicated to vision. The processing of visual information happens over at least 10 functional levels. The neurons in the early visual areas extract simple image features over small local regions of visual space. As the information gets transmitted to higher visual areas, neurons respond to increasingly complex features. With higher levels of information processing the representations become more invariant – less sensitive to the exact feature size, rotation or position. In addition, the receptive field size of neurons in higher visual areas increases, indicating that they are tuned to more global image features. This hierarchical structure allows for efficient computing – different higher visual areas can use the same information computed in the lower areas. The generic scene description that is made in the early visual areas is used by other parts of the brain to complete various different tasks, such as object recognition and categorization, grasping, manipulation, movement planning etc.

Sub-cortical vision

The neural processing of visual information starts already before any of the cortical structures. Photoreceptors on the retina detect light and send signals to retinal ganglion cells. The receptive field size of a photoreceptor is one 100th of a degree (a one degree large receptive field is roughly the size of your thumb, when you have your arm stretched in front of you). The number of inputs to a ganglion cell and therefore its receptive field size depends on the location – in the center of the retina it receives signals from as few as five receptors, while in the periphery a single cell can have several thousand inputs. This implies that the highest spatial resolution is in the center of the retina, also called the fovea. Due to this property primates posses a gaze control mechanism that directs the eyesight so that the features of interest project onto the fovea.

Ganglion cells are selectively tuned to detect various features of the image, such as luminance contrast, color contrast, and direction and speed of movement. All of these features are the primary information used further up the processing pipeline. If there are visual stimuli that are not detectable by ganglion cells, then they are also not available for any cortical visual area.

Ganglion cells project to a region in thalamus called lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), which in turn relays the signals to the cortex. There is no significant computation known to happen in LGN – there is almost a one-to-one correspondence between retinal ganglion and LGN cells. However, only 5% of the inputs to LGN come from the retina – all the other inputs are cortical feedback projections. Although the visual system is often regarded as a feed-forward system, the recurrent feedback connections as well as lateral connections are a common feature seen throughout the visual cortex. The role of the feedback is not yet fully understood but it is proposed to be attributed to processes like attention, expectation, imagination and filling-in the missing information.

Cortical vision

The visual cortex can be divided into three large parts – the occipital part which receives input from LGN and then sends outputs to dorsal and ventral streams. Occipital part includes the areas V1-V4 and MT, which process different aspects of visual information and gives rise to a generic scene representation. The dorsal pathway is involved in the analysis of space and in action planning. The ventral pathway is involved in object recognition and categorization.

V1 is the first cortical area that processes visual information. It is sensitive to edges, gratings, line-endings, motion, color and disparity (angular difference between the projections of a point onto the left and right retinas). The most straight forward example of the hierarchical bottom-up processing is the linear combination of the inputs from several ganglion cells with center-surround receptive fields to create a representation of a bar. This is done by the simple cells of V1 and was first described by the prominent neuroscientists Hubel and Wiesel. This type of information integration implies that the simple cells are sensitive to the exact location of the bar and have a relatively small receptive field. The complex cells of V1 receive inputs from the simple cells, and while also responding to linear oriented patterns they are not sensitive to the exact position of the bar and have a larger receptive field. The computation present in this step could be a MAX-like operation which produces responses similar in amplitude to the larger of the responses pertaining to the individual stimuli. Some simple and complex cells can also detect the end of a bar, and a fraction of V1 cells are also sensitive to local motion within their respective receptive fields.

Area V2 features more sophisticated contour representation including texture-defined contours, illusory contours and contours with border ownership. V2 also builds upon the absolute disparity detection in V1 and features cells that are sensitive to relative disparity which is the difference between the absolute disparities of two points in space. Area V4 receives inputs from V2 and area V3, but very little is known about the computation taking place in V3. Area V4 features neurons that are sensitive to contours with different curvature and vertices with particular angles. Another important feature is the coding for luminance-invariant hue. This is in contrast to V1 where neurons respond to color opponency along the two principle axis (red-green and yellow-blue) rather than the actual color. V4 further outputs to the ventral stream, to inferior temporal cortex (IT) which has been shown through lesion studies to be essential for object discrimination.

Inferior temporal cortex: object discrimination

Inferior temporal cortex (IT) is divided into two areas: TEO and TE. Area TEO integrates information about the shapes and relative positions of multiple contour elements and features mostly cells which respond to simple combinations of features. The receptive field size of TEO neurons is about 3-5 degrees. Area TE features cells with significantly larger receptive fields (10-20 degrees) which respond to faces, hands and complex feature configurations. Cells in TE respond to visual features that are a simpler generalization of the object of interest but more complex than simple bars or spots. This was shown using a stimulus-reduction method by Tanaka et al. where first a response to an object is measured and then the object is replaced by simpler representations until the critical feature that the TE neurons are responding to is narrowed down.

It appears that the neurons in IT pull together various features of medium complexity from lower levels in the ventral stream to build models of object parts. The neurons in TE that are selective to specific objects have to fulfil two seemingly contradictory requirements – selectivity and invariance. They have to distinguish between different objects by the means of sensitivity to features in the retinal images. However, the same object can be viewed from different angles and distances at different light conditions yielding highly dissimilar retinal images of the same object. To treat all these images as equivalent, invariant features must be derived that are robust against certain transformations, such as changes in position, illumination, size on the retina etc. Neurons in area TE show invariance to position and size as well as to partial occlusion, position-in-depth and illumination direction. Rotation in depth has been shown to have the weakest invariance, with the exception if the object is a human face.

Object categories are not yet explicitly present in area TE – a neuron might typically respond to several but not all exemplars of the same category (e.g., images of trees) and it might also respond to exemplars of different categories (e.g., trees and non-trees). Object recognition and classification most probably involves sampling from a larger population of TE neurons as well as receiving inputs from additional brain areas, e.g., those that are responsible for understanding the context of the scene. Recent readout experiments have demonstrated that statistical classifiers (e.g. support vector machines) can be trained to classify objects based on the responses of a small number of TE neurons. Therefore, a population of TE neurons in principle can reliably signal object categories by their combined activity. Interestingly, there are also reports on highly selective neurons in medial temporal lobe that respond to very specific cues, e.g., to the tower of Pisa in different images or to a particular person’s face.

Learning in the Visual System

Learning can alter the visual feature selectivity of neurons, with the effect of learning becoming stronger at higher hierarchical levels. There is no known evidence on learning in the retina and also the orientation maps in V1 seem to be genetically largely predetermined. However, practising orientation identification improves orientation coding in V1 neurons, by increasing the slope of the tuning curve. Similar but larger effects have been seen in V4. In area TE relatively little visual training has noticeable physiological effects on visual perception, on a single cell level as well as in fMRI. For example, morphing two objects into each other increases their perceived similarity. Overall it seems that the even the adult visual cortex is considerably plastic, and the level of plasticity can be significantly increased, e.g., by administering specific drugs or by living in an enriched environment.

Deep Neural Networks

Similarly to the deep hierarchy of the primate visual system, deep learning architectures attempt to model high-level abstractions of the input data by using multiple levels of non-linear transformations. The model proposed by Hubel and Wiesel where information is integrated and propagated in a cascade from retina and LGN to simple cells and complex cells in V1 inspired the creation of one of the first deep learning architectures, the neocognitron – a multilayered artificial neural network model. It was used for different pattern recognition tasks, including the recognition of handwritten characters. However, it took a lot of time to train the network (in the order of days) and since its inception in the 1980s deep learning didn’t get much attention until the mid-2000s with the abundance of digital data and the invention of faster training algorithms. Deep neural networks have proved themselves to be very effective in tasks that not so long ago seemed possible only for humans to perform, such as recognizing the faces of particular people in photos, understanding human speech (to some extent) and translating text from foreign languages. Furthermore, they have proven to be of great assistance in industry and science to search for potential drug candidates, map real neural networks in the brain and predict the functions of proteins. It must be noted that deep learning is only very loosely inspired from the brain and is much more of an achievement of the field of computer science / machine learning than of neuroscience. The basic parallels are that the deep neural networks are composed of units that integrate information inputs in a non-linear manner (neurons) and send signals to each other (synapses) and that there are different levels of increasingly abstract representations of the data. The learning algorithms and mathematical descriptions of the “neurons” used in deep learning are very different from the actual processes taking place in the brain. Therefore, the research in deep learning, while giving a huge push to a more sophisticated artificial intelligence, can give only limited insights about the brain.

References

- Papers on the deep hierarchies in the visual system

- Kruger, N.; Janssen, P.; Kalkan, S.; Lappe, M.; Leonardis, A.; Piater, J.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, A. J.; Wiskott, L. (August 2013). "Deep Hierarchies in the Primate Visual Cortex: What Can We Learn for Computer Vision?". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 35 (8): 1847–1871. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2012.272.

- Poggio, Tomaso; Riesenhuber, Maximilian (1 November 1999). Nature Neuroscience. 2 (11): 1019–1025. doi:doi:10.1038/14819.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Stimulus reduction experiment

- Tanaka, Keiji (March 1996). "Inferotemporal Cortex and Object Vision". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 19 (1): 109–139. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.000545.

- Evidence on learning in the visual system

- Li, Nuo; DiCarlo, James J. (23 September 2010). "Unsupervised Natural Visual Experience Rapidly Reshapes Size-Invariant Object Representation in Inferior Temporal Cortex". Neuron. 67 (6): 1062–1075. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.029.

- Raiguel, S.; Vogels, R.; Mysore, S. G.; Orban, G. A. (14 June 2006). "Learning to See the Difference Specifically Alters the Most Informative V4 Neurons". Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (24): 6589–6602. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0457-06.2006.

- Schoups, A; Vogels, R; Qian, N; Orban, G (2 August 2001). "Practising orientation identification improves orientation coding in V1 neurons". Nature. 412 (6846): 549–53. PMID 11484056.

- A recent and accessible overview of the status quo of the deep learning research

- Jones, Nicola (8 January 2014). "Computer science: The learning machines". Nature. 505 (7482): 146–148. doi:10.1038/505146a.

Motion Perception

Motion Perception is the process of inferring speed and direction of moving objects. Area V5 in humans and area MT (Middle Temporal) in primates are responsible for cortical perception of Motion. Area V5 is part of the extrastriate cortex, which is the region in the occipital region of the brain next to the primary visual cortex. The function of Area V5 is to detect speed and direction of visual stimuli, and integrate local visual motion signals into global motion. Area V1 or Primary Visual cortex is located in the occipital lobe of the brain in both hemispheres. It processes the first stage of cortical processing of visual information. This area contains a complete map of the visual field covered by the eyes. The difference between area V5 and area V1 (Primary Visual Cortex) is that area V5 can integrate motion of local signals or individual parts of an object into a global motion of an entire object. Area V1, on the other hand, responds to local motion that occurs within the receptive field. The estimates from these many neurons are integrated in Area V5.

Movement is defined as changes in retinal illumination over space and time. Motion signals are classified into First order motions and Second order motions. These motion types are briefly described in the following paragraphs.

First-order motion perception refers to the motion perceived when two or more visual stimuli switch on and off over time and produce different motion perceptions. First order motion is also termed "apparent motion,” and it is used in television and film. An example of this is the "Beta movement", which is an illusion in which fixed images seem to move, even though they do not move in reality. These images give the appearance of motion, because they change and move faster than what the eye can detect. This optical illusion happens because the human optic nerve responds to changes of light at ten cycles per second, so any change faster than this rate will be registered as a continuum motion, and not as separate images.

Second order motion refers to the motion that occurs when a moving contour is defined by contrast, texture, flicker or some other quality that does not result in an increase in luminance or motion energy of the image. Evidence suggests that early processing of First order motion and Second order motion is carried out by separate pathways. Second order mechanisms have poorer temporal resolution and are low-pass in terms of the range of spatial frequencies to which they respond. Second-order motion produces a weaker motion aftereffect. First and second-order signals are combined in are V5.

In this chapter, we will analyze the concepts of Motion Perception and Motion Analysis, and explain the reason why these terms should not be used interchangeably. We will analyze the mechanisms by which motion is perceived such as Motion Sensors and Feature Tracking. There exist three main theoretical models that attempt to describe the function of neuronal sensors of motion. Experimental tests have been conducted to confirm whether these models are accurate. Unfortunately, the results of these tests are inconclusive, and it can be said that no single one of these models describes the functioning of Motion Sensors entirely. However, each of these models simulates certain features of Motion Sensors. Some properties of these sensors are described. Finally, this chapter shows some motion illusions, which demonstrate that our sense of motion can be mislead by static external factors that stimulate motion sensors in the same way as motion.

Motion Analysis and Motion Perception

The concepts of Motion Analysis and Motion Perception are often confused as interchangeable. Motion Perception and Motion Analysis are important to each other, but they are not the same.

Motion Analysis refers to the mechanisms in which motion signals are processed. In a similar way in which Motion Perception does not necessarily depend on signals generated by motion of images in the retina, Motion Analysis may or may not lead to motion perception. An example of this phenomenon is Vection, which occurs when a person perceives that she is moving when she is stationary, but the object that she observes is moving. Vection shows that motion of an object can be analyzed, even though it is not perceived as motion coming from the object. This definition of Motion analysis suggests that motion is a fundamental image property. In the visual field, it is analyzed at every point. The results from this analysis are used to derive perceptual information.

Motion Perception refers to the process of acquiring perceptual knowledge about motion of objects and surfaces in an image. Motion is perceived either by delicate local sensors in the retina or by feature tracking. Local motion sensors are specialized neurons sensitive to motion, and analogous to specialized sensors for color. Feature tracking is an indirect way to perceive motion, and it consists of inferring motion from changes in retinal position of objects over time. It is also referred to as third order motion analysis. Feature tracking works by focusing attention to a particular object and observing how its position has changed over time.

Motion Sensors

Detection of motion is the first stage of visual processing, and it happens thanks to specialized neural processes, which respond to information regarding local changes of intensity of images over time. Motion is sensed independently of other image properties at all locations in the image. It has been proven that motion sensors exist, and they operate locally at all points in the image. Motion sensors are dedicated neuronal sensors located in the retina that are capable of detecting a motion produced by two brief and small light flashes that are so close together that they could not be detected by feature tracking. There exist three main models that attempt to describe the way that these specialized sensors work. These models are independent of one another, and they try to model specific characteristics of Motion Perception. Although there is not sufficient evidence to support that any of these models represent the way the visual system (motion sensors particularly) perceives motion, they still correctly model certain functions of these sensors.

The Reichardt Detector

The Reichardt Detector is used to model how motion sensors respond to First order motion signals. When an objects moves from point A in the visual field to point B, two signals are generated: one before the movement began and another one after the movement has completed. This model perceives this motion by detecting changes in luminance at one point on the retina and correlating it with a change in luminance at another point nearby after a short delay. The Reichardt Detector operates based on the principle of correlation (statistical relation that involves dependency). It interprets a motion signal by spatiotemporal correlation of luminance signals at neighboring points. It uses the fact that two receptive fields at different points on the trajectory of a moving object receive a time shifted version of the same signal – a luminance pattern moves along an axis and the signal at one point in the axis is a time shifted version of a previous signal in the axis. The Reichardt Detector model has two spatially separate neighboring detectors. The output signals of the detectors are multiplied (correlated) in the following way: a signal multiplied by a second signal that is the time-shifted version of the original. The same procedure is repeated but in the reverse direction of motion (the signal that was time-shifted becomes the first signal and vice versa). Then, the difference between these two multiplications is taken, and the outcome gives the speed of motion. The response of the detector depends upon the stimulus’ phase, contrast and speed. Many detectors tuned at different speeds are necessary to encode the true speed of the pattern. The most compelling experimental evidence for this kind of detector comes from studies of direction discrimination of barely visible targets.

Motion-Energy Filtering

Motion Energy Filter is a model of Motion Sensors based on the principle of phase invariant filters. This model builds spatio-temporal filters oriented in space-time to match the structure of moving patterns. It consists of separable filters, for which spatial profiles remain the same shape over time but are scaled by the value of the temporal filters. Motion Energy Filters match the structure of moving patterns by adding together separable filters. For each direction of motion, two space-time filters are generated: one, which is symmetric (bar-like), and one which is asymmetric (edge-like). The sum of the squares of these filters is called the motion energy. The difference in the signal for the two directions is called the opponent energy. This result is then divided by the squared output of another filter, which is tuned to static contrast. This division is performed to take into account the effect of contrast in the motion. Motion Energy Filters can model a number of motion phenomenon, but it produces a phase independent measurement, which increases with speed but does not give a reliable value of speed.

Spatiotemporal Gradients

This model of Motion sensors was originally developed in the field of computer vision, and it is based on the principle that the ratio of the temporal derivative of image brightness to the spatial derivative of image brightness gives the speed of motion. It is important to note that at the peaks and troughs of the image, this model will not compute an adequate answer, because the derivative in the denominator would be zero. In order to solve this problem, the first-order and higher-order spatial derivatives with respect to space and time can also be analyzed. Spatiotemporal Gradients is a good model for determining the speed of motion at all points in the image.

Motion Sensors are Orientation-Selective

One of the properties of Motion Sensors is orientation-selectivity, which constrains motion analysis to a single dimension. Motion sensors can only record motion in one dimension along an axis orthogonal to the sensor’s preferred orientation. A stimulus that contains features of a single orientation can only be seen to move in a direction orthogonal to the stimulus’ orientation. One-dimensional motion signals give ambiguous information about the motion of two-dimensional objects. A second stage of motion analysis is necessary in order to resolve the true direction of motion of a 2-D object or pattern. 1-D motion signals from sensors tuned to different orientations are combined to produce an unambiguous 2-D motion signal. Analysis of 2-D motion depends on signals from local broadly oriented sensors as well as on signals from narrowly oriented sensors.

Feature Tracking

Another way in which we perceive motion is through Feature Tracking. Feature Tracking consists of analyzing whether or not the local features of an object have changed positions, and inferring movement from this change. In this section, some features about Feature trackers are mentioned.

Feature trackers fail when a moving stimulus occurs very rapidly. Feature trackers have the advantage over Motion sensors that they can perceive movement of an object even if the movement is separated by intermittent blank intervals. They can also separate these two stages (movements and blank intervals). Motion sensors, on the other hand, would just integrate the blanks with the moving stimulus and see a continuous movement. Feature trackers operate on the locations of identified features. For that reason, they have a minimum distance threshold that matches the precision with which locations of features can be discriminated. Feature trackers do not show motion aftereffects, which are visual illusions that are caused as a result of visual adaptation. Motion aftereffects occur when, after observing a moving stimulus, a stationary object appears to be moving in the opposite direction of the previously observed moving stimulus. It is impossible for this mechanism to monitor multiple motions in different parts of the visual field and at the same time. On the other hand, multiple motions are not a problem for motion sensors, because they operate in parallel across the entire visual field.

Experiments have been conducted using the information above to reach interesting conclusions about feature trackers. Experiments with brief stimuli have shown that color patterns and contrast patterns at high contrasts are not perceived by feature trackers but by motion sensors. Experiments with blank intervals have confirmed that feature tracking can occur with blank intervals in the display. It is only at high contrast that motion sensors perceive the motion of chromatic stimuli and contrast patterns. At low contrasts feature trackers analyze the motion of both chromatic patterns and contrast envelopes and at high contrasts motion sensors analyze contrast envelopes. Experiments in which subjects make multiple motion judgments suggest that feature tracking is a process that occurs under conscious control and that it is the only way we have to analyze the motion of contrast envelopes in low-contrast displays. These results are consistent with the view that the motion of contrast envelopes and color patterns depends on feature tracking except when colors are well above threshold or mean contrast is high. The main conclusion of these experiments is that it is probably feature tracking that allows perception of contrast envelopes and color patterns.

Motion Illusions

As a consequence of the process in which Motion detection works, some static images might seem to us like they are moving. These images give an insight into the assumptions that the visual system makes, and are called visual illusions.

A famous Motion Illusion related to first order motion signals is the Phi phenomenon, which is an optical illusion that makes us perceive movement instead of a sequence of images. This motion illusion allows us to watch movies as a continuum and not as separate images. The phi phenomenon allows a group of frozen images that are changed at a constant speed to be seen as a constant movement. The Phi phenomenon should not be confused with the Beta Movement, because the former is an apparent movement caused by luminous impulses in a sequence, while the later one is an apparent movement caused by luminous stationary impulses.

Motion Illusions happen when Motion Perception, Motion Analysis and the interpretation of these signals are misleading, and our visual system creates illusions about motion. These illusions can be classified according to which process allows them to happen. Illusions are classified as illusions related to motion sensing, 2D integration, and 3D interpretation

The most popular illusions concerning motion sensing are four-stroke motion, RDKs and second order motion signals illusions. The most popular motion illusions concerning 2D integration are Motion Capture, Plaid Motion and Direct Repulsion. Similarly, the ones concerning 3D interpretation are Transformational Motion, Kinetic Depth, Shadow Motion, Biological Motion, Stereokinetic motion, Implicit Figure Motion and 2 Stroke Motion. There are far more Motion Illusions, and they all show something interesting regarding human Motion Detection, Perception and Analysis mechanisms. For more information, visit the following link: http://www.lifesci.sussex.ac.uk/home/George_Mather/Motion/

Open Problems

Although we still do not understand most of the specifics regarding Motion Perception, understanding the mechanisms by which motion is perceived as well as motion illusion can give the reader a good overview of the state of the art in the subject. Some of the open problems regarding Motion Perception are the mechanisms of formation of 3D images in global motion and the Aperture Problem.

Global motion signals from the retina are integrated to arrive at a 2 dimensional global motion signal; however, it is unclear how 3D global motion is formed. The Aperture Problem occurs because each receptive field in the visual system covers only a small piece of the visual world, which leads to ambiguities in perception. The aperture problem refers to the problem of a moving contour that, when observed locally, is consistent with different possibilities of motion. This ambiguity is geometric in origin - motion parallel to the contour cannot be detected, as changes to this component of the motion do not change the images observed through the aperture. The only component that can be measured is the velocity orthogonal to the contour orientation; for that reason, the velocity of the movement could be anything from the family of motions along a line in velocity space. This aperture problem is not only observed in straight contours, but also in smoothly curved ones, since they are approximately straight when observed locally. Although the mechanisms to solve the Aperture Problem are still unknown, there exist some hypothesis on how it could be solved. For example, it could be possible to resolve this problem by combining information across space or from different contours of the same object.

Conclusions

In this chapter, we introduced Motion Perception and the mechanisms by which our visual system detects motion. Motion Illusions showed how Motion signals can be misleading, and consequently lead to incorrect conclusions about motion. It is important to remember that Motion Perception and Motion Analysis are not the same. Motion Sensors and Feature trackers complement each other to make the visual system perceive motion.

Motion Perception is complex, and it is still an open area of research. This chapter describes models about the way that Motion Sensors function, and hypotheses about Feature trackers characteristics; however, more experiments are necessary to learn about the characteristics of these mechanisms and be able to construct models that resemble the actual processes of the visual system more accurately.

The variety of mechanisms of motion analysis and motion perception described in this chapter, as well as the sophistication of the artificial models designed to describe them demonstrate that there is much complexity in the way in which the cortex processes signals from the outside environment. Thousands of specialized neurons integrate and interpret pieces of local signals to form global images of moving objects in our brain. Understanding that so many actors and processes in our bodies must work in concert to perceive motion makes our ability to it all the more remarkable that we as humans are able to do it with such ease.

Color Perception

Introduction

Humans (together with primates like monkeys and gorillas) have the best color perception among mammals [1] . Hence, it is not a coincidence that color plays an important role in a wide variety of aspects. For example, color is useful for discriminating and differentiating objects, surfaces, natural scenery, and even faces [2],[3]. Color is also an important tool for nonverbal communication, including that of emotion [4].

For many decades, it has been a challenge to find the links between the physical properties of color and its perceptual qualities. Usually, these are studied under two different approaches: the behavioral response caused by color (also called psychophysics) and the actual physiological response caused by it [5].

Here we will only focus on the latter. The study of the physiological basis of color vision, about which practically nothing was known before the second half of the twentieth century, has advanced slowly and steadily since 1950. Important progress has been made in many areas, especially at the receptor level. Thanks to molecular biology methods, it has been possible to reveal previously unknown details concerning the genetic basis for the cone pigments. Furthermore, more and more cortical regions have been shown to be influenced by visual stimuli, although the correlation of color perception with wavelength-dependent physiology activity beyond the receptors is not so easy to discern [6].

In this chapter, we aim to explain the basics of the different processes of color perception along the visual path, from the retina in the eye to the visual cortex in the brain. For anatomical details, please refer to Sec. "Anatomy of the Visual System" of this Wikibook.

Color Perception at the Retina

All colors that can be discriminated by humans can be produced by the mixture of just three primary (basic) colors. Inspired by this idea of color mixing, it has been proposed that color is subserved by three classes of sensors, each having a maximal sensitivity to a different part of the visible spectrum [1]. It was first explicitly proposed in 1853 that there are three degrees of freedom in normal color matching [7]. This was later confirmed in 1886 [8] (with remarkably close results to recent studies [9], [10]).

These proposed color sensors are actually the so called cones (Note: In this chapter, we will only deal with cones. Rods contribute to vision only at low light levels. Although they are known to have an effect on color perception, their influence is very small and can be ignored here.) [11]. Cones are of the two types of photoreceptor cells found in the retina, with a significant concentration of them in the fovea. The Table below lists the three types of cone cells. These are distinguished by different types of rhodopsin pigment. Their corresponding absorption curves are shown in the Figure below.

| Name | Higher sensitivity to color | Absorption curve peak [nm] |

|---|---|---|

| S, SWS, B | Blue | 420 |

| M, MWS, G | Green | 530 |

| L, LWS, R | Red | 560 |

Although no consensus has been reached for naming the different cone types, the most widely utilized designations refer either to their action spectra peak or to the color to which they are sensitive themselves (red, green, blue)[6]. In this text, we will use the S-M-L designation (for short, medium, and long wavelength), since these names are more appropriately descriptive. The blue-green-red nomenclature is somewhat misleading, since all types of cones are sensitive to a large range of wavelengths.

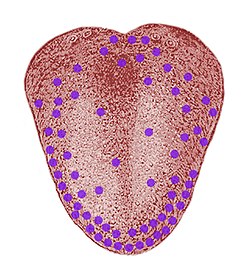

An important feature about the three cone types is their relative distribution in the retina. It turns out that the S-cones present a relatively low concentration through the retina, being completely absent in the most central area of the fovea. Actually, they are too widely spaced to play an important role in spatial vision, although they are capable of mediating weak border perception [12]. The fovea is dominated by L- and M-cones. The proportion of the two latter is usually measured as a ratio. Different values have been reported for the L/M ratio, ranging from 0.67 [13] up to 2 [14], the latter being the most accepted. Why L-cones almost always outnumber the M-cones remains unclear. Surprisingly, the relative cone ratio has almost no significant impact on color vision. This clearly shows that the brain is plastic, capable of making sense out of whatever cone signals it receives [15], [16].

It is also important to note the overlapping of the L- and M-cone absorption spectra. While the S-cone absorption spectrum is clearly separated, the L- and M-cone peaks are only about 30 nm apart, their spectral curves significantly overlapping as well. This results in a high correlation in the photon catches of these two cone classes. This is explained by the fact that in order to achieve the highest possible acuity at the center of the fovea, the visual system treats L- and M-cones equally, not taking into account their absorption spectra. Therefore, any kind of difference leads to a deterioration of the luminance signal [17]. In other words, the small separation between L- and M-cone spectra might be interpreted as a compromise between the needs for high-contrast color vision and high acuity luminance vision. This is congruent with the lack of S-cones in the central part of the fovea, where visual acuity is highest. Furthermore, the close spacing of L- and M-cone absorption spectra might also be explained by their genetic origin. Both cone types are assumed to have evolved "recently" (about 35 million years ago) from a common ancestor, while the S-cones presumably split off from the ancestral receptor much earlier[11].

The spectral absorption functions of the three different types of cone cells are the hallmark of human color vision. This theory solved a long-known problem: although we can see millions of different colors (humans can distinguish between 7 and 10 million different colors[5], our retinas simply do not have enough space to accommodate an individual detector for every color at every retinal location.

From the Retina to the Brain

The signals that are transmitted from the retina to higher levels are not simple point-wise representations of the receptor signals, but rather consist of sophisticated combinations of the receptor signals. The objective of this section is to provide a brief of the paths that some of this information takes.

Once the optical image on the retina is transduced into chemical and electrical signals in the photoreceptors, the amplitude-modulated signals are converted into frequency-modulated representations at the ganglion-cell and higher levels. In these neural cells, the magnitude of the signal is represented in terms of the number of spikes of voltage per second fired by the cell rather than by the voltage difference across the cell membrane. In order to explain and represent the physiological properties of these cells, we will find the concept of receptive fields very useful.