Let

d

∈

N

{\displaystyle d\in \mathbb {N} }

B

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle B\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

partial differential equation on

B

{\displaystyle B}

looks like this:

∀

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

∈

B

:

h

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

,

u

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

,

∂

x

1

u

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

,

…

,

∂

x

d

u

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

,

∂

x

1

2

u

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

,

…

⏞

arbitrary and arbitrarily finitely many partial derivatives,

n

inputs of

h

in total

)

=

0

{\displaystyle \forall (x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d})\in B:h(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d},u(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d}),\overbrace {\partial _{x_{1}}u(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d}),\ldots ,\partial _{x_{d}}u(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d}),\partial _{x_{1}}^{2}u(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d}),\ldots } ^{{\text{arbitrary and arbitrarily finitely many partial derivatives, }}n{\text{ inputs of }}h{\text{ in total}}})=0}

h

{\displaystyle h}

R

n

{\displaystyle \mathbb {R} ^{n}}

R

{\displaystyle \mathbb {R} }

n

∈

N

{\displaystyle n\in \mathbb {N} }

B

{\displaystyle B}

u

:

B

→

R

{\displaystyle u:B\to \mathbb {R} }

In the whole theory of partial differential equations, multiindices are extremely important. Only with their help we are able to write down certain formulas a lot briefer.

Definitions 1.1 :

A

d

{\displaystyle d}

multiindex is a vector

α

∈

N

0

d

{\displaystyle \alpha \in \mathbb {N} _{0}^{d}}

N

0

{\displaystyle \mathbb {N} _{0}}

If

α

=

(

α

1

,

…

,

α

d

)

{\displaystyle \alpha =(\alpha _{1},\ldots ,\alpha _{d})}

absolute value

|

α

|

{\displaystyle |\alpha |}

|

α

|

:=

∑

k

=

1

d

α

k

{\displaystyle |\alpha |:=\sum _{k=1}^{d}\alpha _{k}}

If

α

{\displaystyle \alpha }

d

{\displaystyle d}

B

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle B\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

u

:

B

→

R

{\displaystyle u:B\to \mathbb {R} }

∂

α

u

{\displaystyle \partial _{\alpha }u}

α

{\displaystyle \alpha }

u

{\displaystyle u}

∂

α

u

:=

∂

x

1

α

1

⋯

∂

x

d

α

d

u

{\displaystyle \partial _{\alpha }u:=\partial _{x_{1}}^{\alpha _{1}}\cdots \partial _{x_{d}}^{\alpha _{d}}u}

We classify partial differential equations into several types, because for partial differential equations of one type we will need different solution techniques as for differential equations of other types. We classify them into linear and nonlinear equations, and into equations of different orders.

Definition 1.3 :

Let

n

∈

N

{\displaystyle n\in \mathbb {N} }

n

{\displaystyle n}

n

{\displaystyle n}

∀

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

∈

B

⊆

R

d

:

h

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

,

u

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

,

∂

x

1

u

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

,

…

,

∂

x

d

u

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

,

∂

x

1

2

u

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

,

…

⏞

partial derivatives at most up to order

n

)

=

0

{\displaystyle \forall (x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d})\in B\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}:h(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d},u(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d}),\overbrace {\partial _{x_{1}}u(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d}),\ldots ,\partial _{x_{d}}u(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d}),\partial _{x_{1}}^{2}u(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d}),\ldots } ^{{\text{partial derivatives at most up to order }}n})=0}

Now we are very curious what practical examples of partial differential equations look like after all.

Theorem and definition 1.4 :

If

g

:

R

→

R

{\displaystyle g:\mathbb {R} \to \mathbb {R} }

c

∈

R

{\displaystyle c\in \mathbb {R} }

u

:

R

2

→

R

,

u

(

t

,

x

)

:=

g

(

x

+

c

t

)

{\displaystyle u:\mathbb {R} ^{2}\to \mathbb {R} ,u(t,x):=g(x+ct)}

solves the one-dimensional homogenous transport equation

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

2

:

∂

t

u

(

t

,

x

)

−

c

∂

x

u

(

t

,

x

)

=

0

{\displaystyle \forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} ^{2}:\partial _{t}u(t,x)-c\partial _{x}u(t,x)=0}

Proof : Exercise 2.

We therefore see that the one-dimensional transport equation has many different solutions; one for each continuously differentiable function in existence. However, if we require the solution to have a specific initial state, the solution becomes unique.

Theorem and definition 1.5 :

If

g

:

R

→

R

{\displaystyle g:\mathbb {R} \to \mathbb {R} }

c

∈

R

{\displaystyle c\in \mathbb {R} }

u

:

R

2

→

R

,

u

(

t

,

x

)

:=

g

(

x

+

c

t

)

{\displaystyle u:\mathbb {R} ^{2}\to \mathbb {R} ,u(t,x):=g(x+ct)}

is the unique solution to the initial value problem for the one-dimensional homogenous transport equation

{

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

2

:

∂

t

u

(

t

,

x

)

−

c

∂

x

u

(

t

,

x

)

=

0

∀

x

∈

R

:

u

(

0

,

x

)

=

g

(

x

)

{\displaystyle {\begin{cases}\forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} ^{2}:&\partial _{t}u(t,x)-c\partial _{x}u(t,x)=0\\\forall x\in \mathbb {R} :&u(0,x)=g(x)\end{cases}}}

Proof :

Surely

∀

x

∈

R

:

u

(

0

,

x

)

=

g

(

x

+

c

⋅

0

)

=

g

(

x

)

{\displaystyle \forall x\in \mathbb {R} :u(0,x)=g(x+c\cdot 0)=g(x)}

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

2

:

∂

t

u

(

t

,

x

)

−

c

∂

x

u

(

t

,

x

)

=

0

{\displaystyle \forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} ^{2}:\partial _{t}u(t,x)-c\partial _{x}u(t,x)=0}

Now suppose we have an arbitrary other solution to the initial value problem. Let's name it

v

{\displaystyle v}

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

2

{\displaystyle (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} ^{2}}

μ

(

t

,

x

)

(

ξ

)

:=

v

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

c

ξ

)

{\displaystyle \mu _{(t,x)}(\xi ):=v(t-\xi ,x+c\xi )}

is constant:

d

d

ξ

v

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

c

ξ

)

=

(

∂

t

v

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

c

ξ

)

∂

x

v

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

c

ξ

)

)

(

−

1

c

)

=

−

∂

t

v

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

c

ξ

)

+

c

∂

x

v

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

c

ξ

)

=

0

{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{d\xi }}v(t-\xi ,x+c\xi )={\begin{pmatrix}\partial _{t}v(t-\xi ,x+c\xi )&\partial _{x}v(t-\xi ,x+c\xi )\end{pmatrix}}{\begin{pmatrix}-1\\c\end{pmatrix}}=-\partial _{t}v(t-\xi ,x+c\xi )+c\partial _{x}v(t-\xi ,x+c\xi )=0}

Therefore, in particular

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

2

:

μ

(

t

,

x

)

(

0

)

=

μ

(

t

,

x

)

(

t

)

{\displaystyle \forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} ^{2}:\mu _{(t,x)}(0)=\mu _{(t,x)}(t)}

, which means, inserting the definition of

μ

(

t

,

x

)

{\displaystyle \mu _{(t,x)}}

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

2

:

v

(

t

,

x

)

=

v

(

0

,

x

+

c

t

)

=

initial condition

g

(

x

+

c

t

)

{\displaystyle \forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} ^{2}:v(t,x)=v(0,x+ct){\overset {\text{initial condition}}{=}}g(x+ct)}

, which shows that

u

=

v

{\displaystyle u=v}

v

{\displaystyle v}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

In the next chapter, we will consider the non-homogenous arbitrary-dimensional transport equation.

Have a look at the definition of an ordinary differential equation (see for example the Wikipedia page on that ) and show that every ordinary differential equation is a partial differential equation.

Prove Theorem 1.4 using direct calculation.

What is the order of the transport equation?

Find a function

u

:

R

2

→

R

{\displaystyle u:\mathbb {R} ^{2}\to \mathbb {R} }

∂

t

u

−

2

∂

x

u

=

0

{\displaystyle \partial _{t}u-2\partial _{x}u=0}

∀

x

∈

R

:

u

(

0

,

x

)

=

x

3

{\displaystyle \forall x\in \mathbb {R} :u(0,x)=x^{3}}

In the first chapter, we had already seen the one-dimensional transport equation. In this chapter we will see that we can quite easily generalise the solution method and the uniqueness proof we used there to multiple dimensions. Let

d

∈

N

{\displaystyle d\in \mathbb {N} }

inhomogenous

d

{\displaystyle d}

looks like this:

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

×

R

d

:

∂

t

u

(

t

,

x

)

−

v

⋅

∇

x

u

(

t

,

x

)

=

f

(

t

,

x

)

{\displaystyle \forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}:\partial _{t}u(t,x)-\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}u(t,x)=f(t,x)}

, where

f

:

R

×

R

d

→

R

{\displaystyle f:\mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}\to \mathbb {R} }

v

∈

R

d

{\displaystyle \mathbf {v} \in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

The following definition will become a useful shorthand notation in many occasions. Since we can use it right from the beginning of this chapter, we start with it.

Before we prove a solution formula for the transport equation, we need a theorem from analysis which will play a crucial role in the proof of the solution formula.

Theorem 2.2 : (Leibniz' integral rule)

Let

O

⊆

R

{\displaystyle O\subseteq \mathbb {R} }

B

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle B\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

d

∈

N

{\displaystyle d\in \mathbb {N} }

f

∈

C

1

(

O

×

B

)

{\displaystyle f\in {\mathcal {C}}^{1}(O\times B)}

for all

x

∈

O

{\displaystyle x\in O}

∫

B

|

f

(

x

,

y

)

|

d

y

<

∞

{\displaystyle \int _{B}|f(x,y)|dy<\infty }

for all

x

∈

O

{\displaystyle x\in O}

y

∈

B

{\displaystyle y\in B}

d

d

x

f

(

x

,

y

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dx}}f(x,y)}

there is a function

g

:

B

→

R

{\displaystyle g:B\to \mathbb {R} }

∀

(

x

,

y

)

∈

O

×

B

:

|

∂

x

f

(

x

,

y

)

|

≤

|

g

(

y

)

|

and

∫

B

|

g

(

y

)

|

d

y

<

∞

{\displaystyle \forall (x,y)\in O\times B:|\partial _{x}f(x,y)|\leq |g(y)|{\text{ and }}\int _{B}|g(y)|dy<\infty }

hold, then

d

d

x

∫

B

f

(

x

,

y

)

d

y

=

∫

B

d

d

x

f

(

x

,

y

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dx}}\int _{B}f(x,y)dy=\int _{B}{\frac {d}{dx}}f(x,y)}

We will omit the proof.

Theorem 2.3 :

If

f

∈

C

1

(

R

×

R

d

)

{\displaystyle f\in {\mathcal {C}}^{1}(\mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d})}

g

∈

C

1

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle g\in {\mathcal {C}}^{1}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

v

∈

R

d

{\displaystyle \mathbf {v} \in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

u

:

R

×

R

d

→

R

,

u

(

t

,

x

)

:=

g

(

x

+

v

t

)

+

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle u:\mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}\to \mathbb {R} ,u(t,x):=g(x+\mathbf {v} t)+\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

solves the inhomogenous

d

{\displaystyle d}

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

×

R

d

:

∂

t

u

(

t

,

x

)

−

v

⋅

∇

x

u

(

t

,

x

)

=

f

(

t

,

x

)

{\displaystyle \forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}:\partial _{t}u(t,x)-\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}u(t,x)=f(t,x)}

Note that, as in chapter 1, that there are many solutions, one for each continuously differentiable

g

{\displaystyle g}

Proof :

1.

We show that

u

{\displaystyle u}

g

(

x

+

v

t

)

{\displaystyle g(x+\mathbf {v} t)}

t

,

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

{\displaystyle t,x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d}}

∂

x

n

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

,

n

∈

{

1

,

…

,

d

}

{\displaystyle \partial _{x_{n}}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds,n\in \{1,\ldots ,d\}}

follows from the Leibniz integral rule (see exercise 1). The expression

∂

t

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle \partial _{t}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

we will later in this proof show to be equal to

f

(

t

,

x

)

+

v

⋅

∇

x

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle f(t,x)+\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

which exists because

∇

x

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle \nabla _{x}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

just consists of the derivatives

∂

x

n

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

,

n

∈

{

1

,

…

,

d

}

{\displaystyle \partial _{x_{n}}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds,n\in \{1,\ldots ,d\}}

2.

We show that

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

×

R

d

:

∂

t

u

(

t

,

x

)

−

v

⋅

∇

x

u

(

t

,

x

)

=

f

(

t

,

x

)

{\displaystyle \forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}:\partial _{t}u(t,x)-\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}u(t,x)=f(t,x)}

in three substeps.

2.1

We show that

∂

t

g

(

x

+

v

t

)

−

v

⋅

∇

x

g

(

x

+

v

t

)

=

0

(

∗

)

{\displaystyle \partial _{t}g(x+\mathbf {v} t)-\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}g(x+\mathbf {v} t)=0~~~~~(*)}

This is left to the reader as an exercise in the application of the multi-dimensional chain rule (see exercise 2).

2.2

We show that

∂

t

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

−

v

⋅

∇

x

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

=

f

(

t

,

x

)

(

∗

∗

)

{\displaystyle \partial _{t}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds-\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds=f(t,x)~~~~~(**)}

We choose

F

(

t

,

x

)

:=

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

−

v

s

)

d

s

{\displaystyle F(t,x):=\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x-\mathbf {v} s)ds}

so that we have

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

=

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)=\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

By the multi-dimensional chain rule, we obtain

d

d

t

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

=

(

∂

t

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

∂

x

1

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

⋯

∂

x

d

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

)

(

1

v

)

=

∂

t

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

+

v

⋅

∇

x

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {d}{dt}}F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)&={\begin{pmatrix}\partial _{t}F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)&\partial _{x_{1}}F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)&\cdots &\partial _{x_{d}}F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)\end{pmatrix}}{\begin{pmatrix}1\\\mathbf {v} \end{pmatrix}}\\&=\partial _{t}F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)+\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)\end{aligned}}}

But on the one hand, we have by the fundamental theorem of calculus, that

∂

t

F

(

t

,

x

)

=

f

(

t

,

x

−

v

t

)

{\displaystyle \partial _{t}F(t,x)=f(t,x-\mathbf {v} t)}

∂

t

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

=

f

(

t

,

x

)

{\displaystyle \partial _{t}F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)=f(t,x)}

and on the other hand

∂

x

n

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

=

∂

x

n

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle \partial _{x_{n}}F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)=\partial _{x_{n}}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

, seeing that the differential quotient of the definition of

∂

x

n

{\displaystyle \partial _{x_{n}}}

d

d

t

F

(

t

,

x

+

v

t

)

=

∂

t

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dt}}F(t,x+\mathbf {v} t)=\partial _{t}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

, the second part of the second part of the proof is finished.

2.3

We add

(

∗

)

{\displaystyle (*)}

(

∗

∗

)

{\displaystyle (**)}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

Theorem and definition 2.4 :

If

f

∈

C

1

(

R

×

R

d

)

{\displaystyle f\in {\mathcal {C}}^{1}(\mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d})}

g

∈

C

1

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle g\in {\mathcal {C}}^{1}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

u

:

R

×

R

d

→

R

,

u

(

t

,

x

)

:=

g

(

x

+

v

t

)

+

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle u:\mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}\to \mathbb {R} ,u(t,x):=g(x+\mathbf {v} t)+\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

is the unique solution of the initial value problem of the transport equation

{

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

×

R

d

:

∂

t

u

(

t

,

x

)

−

v

⋅

∇

x

u

(

t

,

x

)

=

f

(

t

,

x

)

∀

x

∈

R

d

:

u

(

0

,

x

)

=

g

(

x

)

{\displaystyle {\begin{cases}\forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}:&\partial _{t}u(t,x)-\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}u(t,x)=f(t,x)\\\forall x\in \mathbb {R} ^{d}:&u(0,x)=g(x)\end{cases}}}

Proof :

Quite easily,

u

(

0

,

x

)

=

g

(

x

+

v

⋅

0

)

+

∫

0

0

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

=

g

(

x

)

{\displaystyle u(0,x)=g(x+\mathbf {v} \cdot 0)+\int _{0}^{0}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds=g(x)}

u

{\displaystyle u}

Assume that

v

{\displaystyle v}

v

=

u

{\displaystyle v=u}

We define

w

:=

u

−

v

{\displaystyle w:=u-v}

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

×

R

d

:

∂

t

w

(

t

,

x

)

−

v

⋅

∇

x

w

(

t

,

x

)

=

(

∂

t

u

(

t

,

x

)

−

v

⋅

∇

x

u

(

t

,

x

)

)

−

(

∂

t

v

(

t

,

x

)

−

v

⋅

∇

x

v

(

t

,

x

)

)

=

f

(

t

,

x

)

−

f

(

t

,

x

)

=

0

(

∗

)

∀

x

∈

R

d

:

w

(

0

,

x

)

=

u

(

0

,

x

)

−

v

(

0

,

x

)

=

g

(

x

)

−

g

(

x

)

=

0

(

∗

∗

)

{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{llll}\forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}:&\partial _{t}w(t,x)-\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}w(t,x)&=(\partial _{t}u(t,x)-\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}u(t,x))-(\partial _{t}v(t,x)-\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}v(t,x))&\\&&=f(t,x)-f(t,x)=0&~~~~~(*)\\\forall x\in \mathbb {R} ^{d}:&w(0,x)=u(0,x)-v(0,x)&=g(x)-g(x)=0&~~~~~(**)\end{array}}}

Analogous to the proof of uniqueness of solutions for the one-dimensional homogenous initial value problem of the transport equation in the first chapter, we define for arbitrary

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

×

R

d

{\displaystyle (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

μ

(

t

,

x

)

(

ξ

)

:=

w

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

v

ξ

)

{\displaystyle \mu _{(t,x)}(\xi ):=w(t-\xi ,x+\mathbf {v} \xi )}

Using the multi-dimensional chain rule, we calculate

μ

(

t

,

x

)

′

(

ξ

)

{\displaystyle \mu _{(t,x)}'(\xi )}

μ

(

t

,

x

)

′

(

ξ

)

:=

d

d

ξ

w

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

v

ξ

)

by defs. of the

′

symbol and

μ

=

(

∂

t

w

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

v

ξ

)

∂

x

1

w

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

v

ξ

)

⋯

∂

x

d

w

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

v

ξ

)

)

(

−

1

v

)

chain rule

=

−

∂

t

w

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

v

ξ

)

+

v

⋅

∇

x

w

(

t

−

ξ

,

x

+

v

ξ

)

=

0

(

∗

)

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mu _{(t,x)}'(\xi )&:={\frac {d}{d\xi }}w(t-\xi ,x+\mathbf {v} \xi )&{\text{ by defs. of the }}'{\text{ symbol and }}\mu \\&={\begin{pmatrix}\partial _{t}w(t-\xi ,x+\mathbf {v} \xi )&\partial _{x_{1}}w(t-\xi ,x+\mathbf {v} \xi )&\cdots &\partial _{x_{d}}w(t-\xi ,x+\mathbf {v} \xi )\end{pmatrix}}{\begin{pmatrix}-1\\\mathbf {v} \end{pmatrix}}&{\text{chain rule}}\\&=-\partial _{t}w(t-\xi ,x+\mathbf {v} \xi )+\mathbf {v} \cdot \nabla _{x}w(t-\xi ,x+\mathbf {v} \xi )&\\&=0&(*)\end{aligned}}}

Therefore, for all

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

×

R

d

{\displaystyle (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

μ

(

t

,

x

)

(

ξ

)

{\displaystyle \mu _{(t,x)}(\xi )}

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

×

R

d

:

w

(

t

,

x

)

=

μ

(

t

,

x

)

(

0

)

=

μ

(

t

,

x

)

(

t

)

=

w

(

0

,

x

+

v

t

)

=

(

∗

∗

)

0

{\displaystyle \forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d}:w(t,x)=\mu _{(t,x)}(0)=\mu _{(t,x)}(t)=w(0,x+\mathbf {v} t){\overset {(**)}{=}}0}

, which shows that

w

=

u

−

v

=

0

{\displaystyle w=u-v=0}

u

=

v

{\displaystyle u=v}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

Let

f

∈

C

1

(

R

×

R

d

)

{\displaystyle f\in {\mathcal {C}}^{1}(\mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{d})}

v

∈

R

d

{\displaystyle \mathbf {v} \in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

n

∈

{

1

,

…

,

d

}

{\displaystyle n\in \{1,\ldots ,d\}}

∂

x

n

∫

0

t

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle \partial _{x_{n}}\int _{0}^{t}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

is equal to

∫

0

t

∂

x

n

f

(

s

,

x

+

v

(

t

−

s

)

)

d

s

{\displaystyle \int _{0}^{t}\partial _{x_{n}}f(s,x+\mathbf {v} (t-s))ds}

and therefore exists.

Let

g

∈

C

1

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle g\in {\mathcal {C}}^{1}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

v

∈

R

d

{\displaystyle \mathbf {v} \in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

∂

t

g

(

x

+

v

t

)

{\displaystyle \partial _{t}g(x+\mathbf {v} t)}

Find the unique solution to the initial value problem

{

∀

(

t

,

x

)

∈

R

×

R

3

:

∂

t

u

(

t

,

x

)

−

(

2

3

4

)

⋅

∇

x

u

(

t

,

x

)

=

t

5

+

x

1

6

+

x

2

7

+

x

3

8

∀

x

∈

R

3

:

u

(

0

,

x

)

=

x

1

9

+

x

2

10

+

x

3

11

{\displaystyle {\begin{cases}\forall (t,x)\in \mathbb {R} \times \mathbb {R} ^{3}:&\partial _{t}u(t,x)-{\begin{pmatrix}2\\3\\4\end{pmatrix}}\cdot \nabla _{x}u(t,x)=t^{5}+x_{1}^{6}+x_{2}^{7}+x_{3}^{8}\\\forall x\in \mathbb {R} ^{3}:&u(0,x)=x_{1}^{9}+x_{2}^{10}+x_{3}^{11}\end{cases}}}

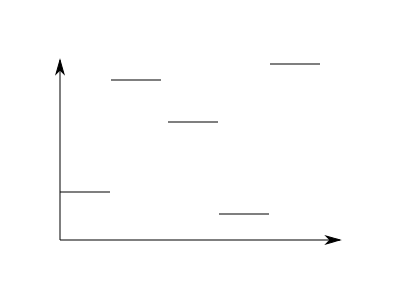

Before we dive deeply into the chapter, let's first motivate the notion of a test function. Let's consider two functions which are piecewise constant on the intervals

[

0

,

1

)

,

[

1

,

2

)

,

[

2

,

3

)

,

[

3

,

4

)

,

[

4

,

5

)

{\displaystyle [0,1),[1,2),[2,3),[3,4),[4,5)}

Let's call the left function

f

1

{\displaystyle f_{1}}

f

2

{\displaystyle f_{2}}

Of course we can easily see that the two functions are different; they differ on the interval

[

4

,

5

)

{\displaystyle [4,5)}

∫

R

φ

(

x

)

f

1

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} }\varphi (x)f_{1}(x)dx}

∫

R

φ

(

x

)

f

2

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} }\varphi (x)f_{2}(x)dx}

for functions

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi }

X

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {X}}}

We proceed with choosing

X

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {X}}}

f

1

≠

f

2

{\displaystyle f_{1}\neq f_{2}}

A

⊆

R

{\displaystyle A\subseteq \mathbb {R} }

characteristic function of

A

{\displaystyle A}

is defined as

χ

A

(

x

)

:=

{

1

x

∈

A

0

x

∉

A

{\displaystyle \chi _{A}(x):={\begin{cases}1&x\in A\\0&x\notin A\end{cases}}}

With this definition, we choose the set of functions

X

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {X}}}

X

:=

{

χ

[

0

,

1

)

,

χ

[

1

,

2

)

,

χ

[

2

,

3

)

,

χ

[

3

,

4

)

,

χ

[

4

,

5

)

}

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {X}}:=\{\chi _{[0,1)},\chi _{[1,2)},\chi _{[2,3)},\chi _{[3,4)},\chi _{[4,5)}\}}

It is easy to see (see exercise 1), that for

n

∈

{

1

,

2

,

3

,

4

,

5

}

{\displaystyle n\in \{1,2,3,4,5\}}

∫

R

χ

[

n

−

1

,

n

)

(

x

)

f

1

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} }\chi _{[n-1,n)}(x)f_{1}(x)dx}

equals the value of

f

1

{\displaystyle f_{1}}

[

n

−

1

,

n

)

{\displaystyle [n-1,n)}

f

2

{\displaystyle f_{2}}

[

n

−

1

,

n

)

,

n

∈

{

1

,

2

,

3

,

4

,

5

}

{\displaystyle [n-1,n),n\in \{1,2,3,4,5\}}

f

1

=

f

2

⇔

∀

φ

∈

X

:

∫

R

φ

(

x

)

f

1

(

x

)

d

x

=

∫

R

φ

(

x

)

f

2

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle f_{1}=f_{2}\Leftrightarrow \forall \varphi \in {\mathcal {X}}:\int _{\mathbb {R} }\varphi (x)f_{1}(x)dx=\int _{\mathbb {R} }\varphi (x)f_{2}(x)dx}

This obviously needs five evaluations of each integral, as

#

X

=

5

{\displaystyle \#{\mathcal {X}}=5}

Since we used the functions in

X

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {X}}}

f

1

{\displaystyle f_{1}}

f

2

{\displaystyle f_{2}}

test functions . What we ask ourselves now is if this notion generalises from functions like

f

1

{\displaystyle f_{1}}

f

2

{\displaystyle f_{2}}

In order to write down the definition of a bump function more shortly, we need the following two definitions:

Now we are ready to define a bump function in a brief way:

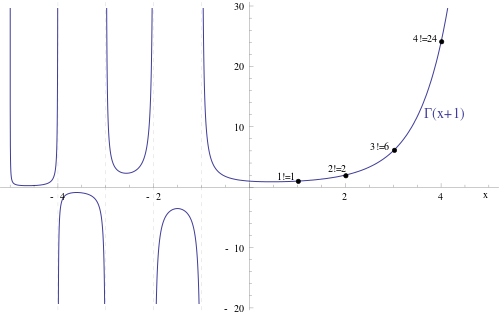

These two properties make the function really look like a bump, as the following example shows:

The standard mollifier

η

{\displaystyle \eta }

d

=

1

{\displaystyle d=1}

Example 3.4: The standard mollifier

η

{\displaystyle \eta }

η

:

R

d

→

R

,

η

(

x

)

=

1

c

{

e

−

1

1

−

‖

x

‖

2

if

‖

x

‖

2

<

1

0

if

‖

x

‖

2

≥

1

{\displaystyle \eta :\mathbb {R} ^{d}\to \mathbb {R} ,\eta (x)={\frac {1}{c}}{\begin{cases}e^{-{\frac {1}{1-\|x\|^{2}}}}&{\text{ if }}\|x\|_{2}<1\\0&{\text{ if }}\|x\|_{2}\geq 1\end{cases}}}

, where

c

:=

∫

B

1

(

0

)

e

−

1

1

−

‖

x

‖

2

d

x

{\displaystyle c:=\int _{B_{1}(0)}e^{-{\frac {1}{1-\|x\|^{2}}}}dx}

As for the bump functions, in order to write down the definition of Schwartz functions shortly, we first need two helpful definitions.

Now we are ready to define a Schwartz function.

Definition 3.7 :

We call

ϕ

:

R

d

→

R

{\displaystyle \phi :\mathbb {R} ^{d}\to \mathbb {R} }

Schwartz function iff the following two conditions are satisfied:

ϕ

∈

C

∞

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle \phi \in {\mathcal {C}}^{\infty }(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

∀

α

,

β

∈

N

0

d

:

‖

x

α

∂

β

ϕ

‖

∞

<

∞

{\displaystyle \forall \alpha ,\beta \in \mathbb {N} _{0}^{d}:\|x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\phi \|_{\infty }<\infty }

By

x

α

∂

β

ϕ

{\displaystyle x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\phi }

x

↦

x

α

∂

β

ϕ

(

x

)

{\displaystyle x\mapsto x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\phi (x)}

f

(

x

,

y

)

=

e

−

x

2

−

y

2

{\displaystyle f(x,y)=e^{-x^{2}-y^{2}}}

Example 3.8 :

The function

f

:

R

2

→

R

,

f

(

x

,

y

)

=

e

−

x

2

−

y

2

{\displaystyle f:\mathbb {R} ^{2}\to \mathbb {R} ,f(x,y)=e^{-x^{2}-y^{2}}}

is a Schwartz function.

Theorem 3.9 :

Every bump function is also a Schwartz function.

This means for example that the standard mollifier is a Schwartz function.

Proof :

Let

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi }

φ

∈

C

∞

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle \varphi \in {\mathcal {C}}^{\infty }(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

R

>

0

{\displaystyle R>0}

supp

φ

⊆

B

R

(

0

)

¯

{\displaystyle {\text{supp }}\varphi \subseteq {\overline {B_{R}(0)}}}

, as in

R

d

{\displaystyle \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

α

,

β

∈

N

0

d

{\displaystyle \alpha ,\beta \in \mathbb {N} _{0}^{d}}

‖

x

α

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

‖

∞

:=

sup

x

∈

R

d

|

x

α

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

|

=

sup

x

∈

B

R

(

0

)

¯

|

x

α

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

|

supp

φ

⊆

B

R

(

0

)

¯

=

sup

x

∈

B

R

(

0

)

¯

(

|

x

α

|

|

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

|

)

rules for absolute value

≤

sup

x

∈

B

R

(

0

)

¯

(

R

|

α

|

|

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

|

)

∀

i

∈

{

1

,

…

,

d

}

,

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

∈

B

R

(

0

)

¯

:

|

x

i

|

≤

R

<

∞

Extreme value theorem

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\|x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)\|_{\infty }&:=\sup _{x\in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}|x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)|&\\&=\sup _{x\in {\overline {B_{R}(0)}}}|x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)|&{\text{supp }}\varphi \subseteq {\overline {B_{R}(0)}}\\&=\sup _{x\in {\overline {B_{R}(0)}}}\left(|x^{\alpha }||\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)|\right)&{\text{rules for absolute value}}\\&\leq \sup _{x\in {\overline {B_{R}(0)}}}\left(R^{|\alpha |}|\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)|\right)&\forall i\in \{1,\ldots ,d\},(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d})\in {\overline {B_{R}(0)}}:|x_{i}|\leq R\\&<\infty &{\text{Extreme value theorem}}\end{aligned}}}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

Now we define what convergence of a sequence of bump (Schwartz) functions to a bump (Schwartz) function means.

Definition 3.11 :

We say that the sequence of Schwartz functions

(

ϕ

i

)

i

∈

N

{\displaystyle (\phi _{i})_{i\in \mathbb {N} }}

ϕ

{\displaystyle \phi }

∀

α

,

β

∈

N

0

d

:

‖

x

α

∂

β

ϕ

i

−

x

α

∂

β

ϕ

‖

∞

→

0

,

i

→

∞

{\displaystyle \forall \alpha ,\beta \in \mathbb {N} _{0}^{d}:\|x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\phi _{i}-x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\phi \|_{\infty }\to 0,i\to \infty }

Theorem 3.12 :

Let

(

φ

i

)

i

∈

N

{\displaystyle (\varphi _{i})_{i\in \mathbb {N} }}

φ

i

→

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi _{i}\to \varphi }

φ

i

→

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi _{i}\to \varphi }

Proof :

Let

O

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle O\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

(

φ

l

)

l

∈

N

{\displaystyle (\varphi _{l})_{l\in \mathbb {N} }}

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

φ

l

→

φ

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \varphi _{l}\to \varphi \in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

K

⊂

R

d

{\displaystyle K\subset \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

supp

φ

l

{\displaystyle {\text{supp }}\varphi _{l}}

supp

φ

⊆

K

{\displaystyle {\text{supp }}\varphi \subseteq K}

‖

φ

l

−

φ

‖

∞

≥

|

c

|

{\displaystyle \|\varphi _{l}-\varphi \|_{\infty }\geq |c|}

c

∈

R

{\displaystyle c\in \mathbb {R} }

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi }

K

{\displaystyle K}

φ

l

→

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi _{l}\to \varphi }

In

R

d

{\displaystyle \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

K

⊂

B

R

(

0

)

{\displaystyle K\subset B_{R}(0)}

R

>

0

{\displaystyle R>0}

α

,

β

∈

N

0

d

{\displaystyle \alpha ,\beta \in \mathbb {N} _{0}^{d}}

‖

x

α

∂

β

φ

l

−

x

α

∂

β

φ

‖

∞

=

sup

x

∈

R

d

|

x

α

∂

β

φ

l

(

x

)

−

x

α

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

|

definition of the supremum norm

=

sup

x

∈

B

R

(

0

)

|

x

α

∂

β

φ

l

(

x

)

−

x

α

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

|

as

supp

φ

l

,

supp

φ

⊆

K

⊂

B

R

(

0

)

≤

R

|

α

|

sup

x

∈

B

R

(

0

)

|

∂

β

φ

l

(

x

)

−

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

|

∀

i

∈

{

1

,

…

,

d

}

,

(

x

1

,

…

,

x

d

)

∈

B

R

(

0

)

¯

:

|

x

i

|

≤

R

=

R

|

α

|

sup

x

∈

R

d

|

∂

β

φ

l

(

x

)

−

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

|

as

supp

φ

l

,

supp

φ

⊆

K

⊂

B

R

(

0

)

=

R

|

α

|

‖

∂

β

φ

l

(

x

)

−

∂

β

φ

(

x

)

‖

∞

definition of the supremum norm

→

0

,

l

→

∞

since

φ

l

→

φ

in

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\|x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\varphi _{l}-x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\varphi \|_{\infty }&=\sup _{x\in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}\left|x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\varphi _{l}(x)-x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)\right|&{\text{ definition of the supremum norm}}\\&=\sup _{x\in B_{R}(0)}\left|x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\varphi _{l}(x)-x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)\right|&{\text{ as }}{\text{supp }}\varphi _{l},{\text{supp }}\varphi \subseteq K\subset B_{R}(0)\\&\leq R^{|\alpha |}\sup _{x\in B_{R}(0)}\left|\partial _{\beta }\varphi _{l}(x)-\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)\right|&\forall i\in \{1,\ldots ,d\},(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{d})\in {\overline {B_{R}(0)}}:|x_{i}|\leq R\\&=R^{|\alpha |}\sup _{x\in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}\left|\partial _{\beta }\varphi _{l}(x)-\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)\right|&{\text{ as }}{\text{supp }}\varphi _{l},{\text{supp }}\varphi \subseteq K\subset B_{R}(0)\\&=R^{|\alpha |}\left\|\partial _{\beta }\varphi _{l}(x)-\partial _{\beta }\varphi (x)\right\|_{\infty }&{\text{ definition of the supremum norm}}\\&\to 0,l\to \infty &{\text{ since }}\varphi _{l}\to \varphi {\text{ in }}{\mathcal {D}}(O)\end{aligned}}}

Therefore the sequence converges with respect to the notion of convergence for Schwartz functions.

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

In this section, we want to show that we can test equality of continuous functions

f

,

g

{\displaystyle f,g}

∫

R

d

f

(

x

)

φ

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}f(x)\varphi (x)dx}

∫

R

d

g

(

x

)

φ

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}g(x)\varphi (x)dx}

for all

φ

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \varphi \in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

φ

∈

S

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle \varphi \in {\mathcal {S}}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

D

(

O

)

⊂

S

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {D}}(O)\subset {\mathcal {S}}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

But before we are able to show that, we need a modified mollifier, where the modification is dependent of a parameter, and two lemmas about that modified mollifier.

Definition 3.13 :

For

R

∈

R

>

0

{\displaystyle R\in \mathbb {R} _{>0}}

η

R

:

R

d

→

R

,

η

R

(

x

)

=

η

(

x

R

)

/

R

d

{\displaystyle \eta _{R}:\mathbb {R} ^{d}\to \mathbb {R} ,\eta _{R}(x)=\eta \left({\frac {x}{R}}\right){\big /}R^{d}}

Lemma 3.14 :

Let

R

∈

R

>

0

{\displaystyle R\in \mathbb {R} _{>0}}

supp

η

R

=

B

R

(

0

)

¯

{\displaystyle {\text{supp }}\eta _{R}={\overline {B_{R}(0)}}}

Proof :

From the definition of

η

{\displaystyle \eta }

supp

η

=

B

1

(

0

)

¯

{\displaystyle {\text{supp }}\eta ={\overline {B_{1}(0)}}}

Further, for

R

∈

R

>

0

{\displaystyle R\in \mathbb {R} _{>0}}

x

R

∈

B

1

(

0

)

¯

⇔

‖

x

R

‖

≤

1

⇔

‖

x

‖

≤

R

⇔

x

∈

B

R

(

0

)

¯

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {x}{R}}\in {\overline {B_{1}(0)}}&\Leftrightarrow \left\|{\frac {x}{R}}\right\|\leq 1\\&\Leftrightarrow \|x\|\leq R\\&\Leftrightarrow x\in {\overline {B_{R}(0)}}\end{aligned}}}

Therefore, and since

x

∈

supp

η

R

⇔

x

R

∈

supp

η

{\displaystyle x\in {\text{supp }}\eta _{R}\Leftrightarrow {\frac {x}{R}}\in {\text{supp }}\eta }

, we have:

x

∈

supp

η

R

⇔

x

∈

B

R

(

0

)

¯

{\displaystyle x\in {\text{supp }}\eta _{R}\Leftrightarrow x\in {\overline {B_{R}(0)}}}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

In order to prove the next lemma, we need the following theorem from integration theory:

Theorem 3.15 : (Multi-dimensional integration by substitution)

If

O

,

U

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle O,U\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

ψ

:

U

→

O

{\displaystyle \psi :U\to O}

∫

O

f

(

x

)

d

x

=

∫

U

f

(

ψ

(

x

)

)

|

det

J

ψ

(

x

)

|

d

x

{\displaystyle \int _{O}f(x)dx=\int _{U}f(\psi (x))|\det J_{\psi }(x)|dx}

We will omit the proof, as understanding it is not very important for understanding this wikibook.

Lemma 3.16 :

Let

R

∈

R

>

0

{\displaystyle R\in \mathbb {R} _{>0}}

∫

R

d

η

R

(

x

)

d

x

=

1

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}\eta _{R}(x)dx=1}

Proof :

∫

R

d

η

R

(

x

)

d

x

=

∫

R

d

η

(

x

R

)

/

R

d

d

x

Def. of

η

R

=

∫

R

d

η

(

x

)

d

x

integration by substitution using

x

↦

R

x

=

∫

B

1

(

0

)

η

(

x

)

d

x

Def. of

η

=

∫

B

1

(

0

)

e

−

1

1

−

‖

x

‖

d

x

∫

B

1

(

0

)

e

−

1

1

−

‖

x

‖

d

x

Def. of

η

=

1

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}\eta _{R}(x)dx&=\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}\eta \left({\frac {x}{R}}\right){\big /}R^{d}dx&{\text{Def. of }}\eta _{R}\\&=\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}\eta (x)dx&{\text{integration by substitution using }}x\mapsto Rx\\&=\int _{B_{1}(0)}\eta (x)dx&{\text{Def. of }}\eta \\&={\frac {\int _{B_{1}(0)}e^{-{\frac {1}{1-\|x\|}}}dx}{\int _{B_{1}(0)}e^{-{\frac {1}{1-\|x\|}}}dx}}&{\text{Def. of }}\eta \\&=1\end{aligned}}}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

Now we are ready to prove the ‘testing’ property of test functions:

Theorem 3.17 :

Let

f

,

g

:

R

d

→

R

{\displaystyle f,g:\mathbb {R} ^{d}\to \mathbb {R} }

∀

φ

∈

D

(

O

)

:

∫

R

d

φ

(

x

)

f

(

x

)

d

x

=

∫

R

d

φ

(

x

)

g

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle \forall \varphi \in {\mathcal {D}}(O):\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}\varphi (x)f(x)dx=\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}\varphi (x)g(x)dx}

then

f

=

g

{\displaystyle f=g}

Proof :

Let

x

∈

R

d

{\displaystyle x\in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

ϵ

∈

R

>

0

{\displaystyle \epsilon \in \mathbb {R} _{>0}}

f

{\displaystyle f}

δ

∈

R

>

0

{\displaystyle \delta \in \mathbb {R} _{>0}}

∀

y

∈

B

δ

(

x

)

¯

:

|

f

(

x

)

−

f

(

y

)

|

<

ϵ

{\displaystyle \forall y\in {\overline {B_{\delta }(x)}}:|f(x)-f(y)|<\epsilon }

Then we have

|

f

(

x

)

−

∫

R

d

f

(

y

)

η

δ

(

x

−

y

)

d

y

|

=

|

∫

R

d

(

f

(

x

)

−

f

(

y

)

)

η

δ

(

x

−

y

)

d

y

|

lemma 3.16

≤

∫

R

d

|

f

(

x

)

−

f

(

y

)

|

η

δ

(

x

−

y

)

d

y

triangle ineq. for the

∫

and

η

δ

≥

0

=

∫

B

δ

(

0

)

¯

|

f

(

x

)

−

f

(

y

)

|

η

δ

(

x

−

y

)

d

y

lemma 3.14

≤

∫

B

δ

(

0

)

¯

ϵ

η

δ

(

x

−

y

)

d

y

monotony of the

∫

≤

ϵ

lemma 3.16 and

η

δ

≥

0

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left|f(x)-\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}f(y)\eta _{\delta }(x-y)dy\right|&=\left|\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}(f(x)-f(y))\eta _{\delta }(x-y)dy\right|&{\text{lemma 3.16}}\\&\leq \int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}|f(x)-f(y)|\eta _{\delta }(x-y)dy&{\text{triangle ineq. for the }}\int {\text{ and }}\eta _{\delta }\geq 0\\&=\int _{\overline {B_{\delta }(0)}}|f(x)-f(y)|\eta _{\delta }(x-y)dy&{\text{lemma 3.14}}\\&\leq \int _{\overline {B_{\delta }(0)}}\epsilon \eta _{\delta }(x-y)dy&{\text{monotony of the }}\int \\&\leq \epsilon &{\text{lemma 3.16 and }}\eta _{\delta }\geq 0\end{aligned}}}

Therefore,

∫

R

d

f

(

y

)

η

δ

(

x

−

y

)

d

y

→

f

(

x

)

,

δ

→

0

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}f(y)\eta _{\delta }(x-y)dy\to f(x),\delta \to 0}

∫

R

d

g

(

y

)

η

δ

(

x

−

y

)

d

y

→

g

(

x

)

,

δ

→

0

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}g(y)\eta _{\delta }(x-y)dy\to g(x),\delta \to 0}

∀

δ

∈

R

>

0

:

∫

R

d

g

(

y

)

η

δ

(

x

−

y

)

d

y

=

∫

R

d

f

(

y

)

η

δ

(

x

−

y

)

d

y

{\displaystyle \forall \delta \in \mathbb {R} _{>0}:\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}g(y)\eta _{\delta }(x-y)dy=\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}f(y)\eta _{\delta }(x-y)dy}

As limits in the reals are unique, it follows that

f

(

x

)

=

g

(

x

)

{\displaystyle f(x)=g(x)}

x

∈

R

d

{\displaystyle x\in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

f

=

g

{\displaystyle f=g}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

Remark 3.18 :

Let

f

,

g

:

R

d

→

R

{\displaystyle f,g:\mathbb {R} ^{d}\to \mathbb {R} }

∀

φ

∈

S

(

R

d

)

:

∫

R

d

φ

(

x

)

f

(

x

)

d

x

=

∫

R

d

φ

(

x

)

g

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle \forall \varphi \in {\mathcal {S}}(\mathbb {R} ^{d}):\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}\varphi (x)f(x)dx=\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}\varphi (x)g(x)dx}

then

f

=

g

{\displaystyle f=g}

Proof :

This follows from all bump functions being Schwartz functions, which is why the requirements for theorem 3.17 are met.

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

Let

b

∈

R

{\displaystyle b\in \mathbb {R} }

f

:

R

→

R

{\displaystyle f:\mathbb {R} \to \mathbb {R} }

[

b

−

1

,

b

)

{\displaystyle [b-1,b)}

∀

y

∈

[

b

−

1

,

b

)

:

∫

R

χ

[

b

−

1

,

b

)

(

x

)

f

(

x

)

d

x

=

f

(

y

)

{\displaystyle \forall y\in [b-1,b):\int _{\mathbb {R} }\chi _{[b-1,b)}(x)f(x)dx=f(y)}

Prove that the standard mollifier as defined in example 3.4 is a bump function by proceeding as follows:

Prove that the function

x

↦

{

e

−

1

x

x

>

0

0

x

≤

0

{\displaystyle x\mapsto {\begin{cases}e^{-{\frac {1}{x}}}&x>0\\0&x\leq 0\end{cases}}}

is contained in

C

∞

(

R

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {C}}^{\infty }(\mathbb {R} )}

Prove that the function

x

↦

1

−

‖

x

‖

{\displaystyle x\mapsto 1-\|x\|}

is contained in

C

∞

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {C}}^{\infty }(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

Conclude that

η

∈

C

∞

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle \eta \in {\mathcal {C}}^{\infty }(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

Prove that

supp

η

{\displaystyle {\text{supp }}\eta }

supp

η

{\displaystyle {\text{supp }}\eta }

Let

O

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle O\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

φ

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \varphi \in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

ϕ

∈

S

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle \phi \in {\mathcal {S}}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

α

,

β

∈

N

0

d

{\displaystyle \alpha ,\beta \in \mathbb {N} _{0}^{d}}

∂

α

φ

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \partial _{\alpha }\varphi \in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

x

α

∂

β

ϕ

∈

S

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle x^{\alpha }\partial _{\beta }\phi \in {\mathcal {S}}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

Let

O

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle O\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

φ

1

,

…

,

φ

n

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \varphi _{1},\ldots ,\varphi _{n}\in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

c

1

,

…

,

c

n

∈

R

{\displaystyle c_{1},\ldots ,c_{n}\in \mathbb {R} }

∑

j

=

1

n

c

j

φ

j

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \sum _{j=1}^{n}c_{j}\varphi _{j}\in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

Let

ϕ

1

,

…

,

ϕ

n

{\displaystyle \phi _{1},\ldots ,\phi _{n}}

c

1

,

…

,

c

n

∈

R

{\displaystyle c_{1},\ldots ,c_{n}\in \mathbb {R} }

∑

j

=

1

n

c

j

ϕ

j

{\displaystyle \sum _{j=1}^{n}c_{j}\phi _{j}}

Let

α

∈

N

0

d

{\displaystyle \alpha \in \mathbb {N} _{0}^{d}}

p

(

x

)

:=

∑

ς

≤

α

c

ς

x

ς

{\displaystyle p(x):=\sum _{\varsigma \leq \alpha }c_{\varsigma }x^{\varsigma }}

ϕ

l

→

ϕ

{\displaystyle \phi _{l}\to \phi }

p

ϕ

l

→

p

ϕ

{\displaystyle p\phi _{l}\to p\phi }

Theorem 4.3 :

Let

T

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}}

T

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}}

Proof :

Let

T

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}}

O

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle O\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

1.

We show that

T

(

φ

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}(\varphi )}

φ

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \varphi \in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

Due to theorem 3.9, every bump function is a Schwartz function, which is why the expression

T

(

φ

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}(\varphi )}

makes sense for every

φ

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \varphi \in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

2.

We show that the restriction is linear.

Let

a

,

b

∈

R

{\displaystyle a,b\in \mathbb {R} }

φ

,

ϑ

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \varphi ,\vartheta \in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi }

ϑ

{\displaystyle \vartheta }

∀

a

,

b

∈

R

,

φ

,

ϑ

∈

D

(

O

)

:

T

(

a

φ

+

b

ϑ

)

=

a

T

(

φ

)

+

b

T

(

ϑ

)

{\displaystyle \forall a,b\in \mathbb {R} ,\varphi ,\vartheta \in {\mathcal {D}}(O):{\mathcal {T}}(a\varphi +b\vartheta )=a{\mathcal {T}}(\varphi )+b{\mathcal {T}}(\vartheta )}

due to the linearity of

T

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}}

T

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}}

3.

We show that the restriction of

T

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}}

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

φ

l

→

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi _{l}\to \varphi }

φ

l

→

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi _{l}\to \varphi }

T

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}}

T

(

φ

l

)

→

T

(

φ

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}(\varphi _{l})\to {\mathcal {T}}(\varphi )}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

The convolution of two functions may not always exist, but there are sufficient conditions for it to exist:

Theorem 4.5 :

Let

p

,

q

∈

[

1

,

∞

]

{\displaystyle p,q\in [1,\infty ]}

1

p

+

1

q

=

1

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{p}}+{\frac {1}{q}}=1}

f

∈

L

p

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle f\in L^{p}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

g

∈

L

q

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle g\in L^{q}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

y

∈

O

{\displaystyle y\in O}

∫

R

d

f

(

x

)

g

(

y

−

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}f(x)g(y-x)dx}

has a well-defined real value.

Proof :

Due to Hölder's inequality ,

∫

R

d

|

f

(

x

)

g

(

y

−

x

)

|

d

x

≤

(

∫

R

d

|

f

(

x

)

|

p

d

x

)

1

/

p

(

∫

R

d

|

g

(

y

−

x

)

|

q

d

x

)

1

/

q

<

∞

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}|f(x)g(y-x)|dx\leq \left(\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}|f(x)|^{p}dx\right)^{1/p}\left(\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}|g(y-x)|^{q}dx\right)^{1/q}<\infty }

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

We shall now prove that the convolution is commutative, i. e.

f

∗

g

=

g

∗

f

{\displaystyle f*g=g*f}

Proof :

We apply multi-dimensional integration by substitution using the diffeomorphism

x

↦

y

−

x

{\displaystyle x\mapsto y-x}

(

f

∗

g

)

(

y

)

=

∫

R

d

f

(

x

)

g

(

y

−

x

)

d

x

=

∫

R

d

f

(

y

−

x

)

g

(

x

)

d

x

=

(

g

∗

f

)

(

y

)

{\displaystyle (f*g)(y)=\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}f(x)g(y-x)dx=\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}f(y-x)g(x)dx=(g*f)(y)}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

Lemma 4.7 :

Let

O

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle O\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

f

∈

L

1

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle f\in L^{1}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

f

∗

η

δ

∈

C

∞

(

R

d

)

{\displaystyle f*\eta _{\delta }\in {\mathcal {C}}^{\infty }(\mathbb {R} ^{d})}

Proof :

Let

α

∈

N

0

d

{\displaystyle \alpha \in \mathbb {N} _{0}^{d}}

y

∈

R

d

{\displaystyle y\in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

∫

R

d

|

f

(

x

)

∂

α

η

δ

(

y

−

x

)

|

d

x

≤

‖

∂

α

η

δ

‖

∞

∫

R

d

|

f

(

x

)

|

d

x

{\displaystyle \int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}|f(x)\partial _{\alpha }\eta _{\delta }(y-x)|dx\leq \|\partial _{\alpha }\eta _{\delta }\|_{\infty }\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}|f(x)|dx}

and further

|

f

(

x

)

∂

α

η

δ

(

y

−

x

)

|

≤

|

f

(

x

)

|

{\displaystyle |f(x)\partial _{\alpha }\eta _{\delta }(y-x)|\leq |f(x)|}

Leibniz' integral rule (theorem 2.2) is applicable, and by repeated application of Leibniz' integral rule we obtain

∂

α

f

∗

η

δ

=

f

∗

∂

α

η

δ

{\displaystyle \partial _{\alpha }f*\eta _{\delta }=f*\partial _{\alpha }\eta _{\delta }}

◻

{\displaystyle \Box }

In this section, we shortly study a class of distributions which we call regular distributions . In particular, we will see that for certain kinds of functions there exist corresponding distributions.

Two questions related to this definition could be asked: Given a function

f

:

R

d

→

R

{\displaystyle f:\mathbb {R} ^{d}\to \mathbb {R} }

T

f

:

D

(

O

)

→

R

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}:{\mathcal {D}}(O)\to \mathbb {R} }

O

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle O\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

T

f

(

φ

)

:=

∫

O

f

(

x

)

φ

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}(\varphi ):=\int _{O}f(x)\varphi (x)dx}

well-defined and a distribution? Or is

T

f

:

S

(

R

d

)

→

R

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}:{\mathcal {S}}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})\to \mathbb {R} }

T

f

(

ϕ

)

:=

∫

R

d

f

(

x

)

ϕ

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}(\phi ):=\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}f(x)\phi (x)dx}

well-defined and a tempered distribution? In general, the answer to these two questions is no, but both questions can be answered with yes if the respective function

f

{\displaystyle f}

f

{\displaystyle f}

Now we are ready to give some sufficient conditions on

f

{\displaystyle f}

T

f

:

D

(

O

)

→

R

,

T

f

(

φ

)

:=

∫

O

f

(

x

)

φ

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}:{\mathcal {D}}(O)\to \mathbb {R} ,{\mathcal {T}}_{f}(\varphi ):=\int _{O}f(x)\varphi (x)dx}

or

T

f

:

S

(

R

d

)

→

R

,

T

f

(

ϕ

)

:=

∫

R

d

f

(

x

)

ϕ

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}:{\mathcal {S}}(\mathbb {R} ^{d})\to \mathbb {R} ,{\mathcal {T}}_{f}(\phi ):=\int _{\mathbb {R} ^{d}}f(x)\phi (x)dx}

Theorem 4.11 :

Let

O

⊆

R

d

{\displaystyle O\subseteq \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

f

:

O

→

R

{\displaystyle f:O\to \mathbb {R} }

T

f

:

D

(

O

)

→

R

,

T

f

(

φ

)

:=

∫

O

f

(

x

)

φ

(

x

)

d

x

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}:{\mathcal {D}}(O)\to \mathbb {R} ,{\mathcal {T}}_{f}(\varphi ):=\int _{O}f(x)\varphi (x)dx}

is a regular distribution iff

f

∈

L

loc

1

(

O

)

{\displaystyle f\in L_{\text{loc}}^{1}(O)}

Proof :

1.

We show that if

f

∈

L

loc

1

(

O

)

{\displaystyle f\in L_{\text{loc}}^{1}(O)}

T

f

:

D

(

O

)

→

R

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}:{\mathcal {D}}(O)\to \mathbb {R} }

Well-definedness follows from the triangle inequality of the integral and the monotony of the integral:

|

∫

U

φ

(

x

)

f

(

x

)

d

x

|

≤

∫

U

|

φ

(

x

)

f

(

x

)

|

d

x

=

∫

supp

φ

|

φ

(

x

)

f

(

x

)

|

d

x

≤

∫

supp

φ

‖

φ

‖

∞

|

f

(

x

)

|

d

x

=

‖

φ

‖

∞

∫

supp

φ

|

f

(

x

)

|

d

x

<

∞

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left|\int _{U}\varphi (x)f(x)dx\right|\leq \int _{U}|\varphi (x)f(x)|dx=\int _{{\text{supp }}\varphi }|\varphi (x)f(x)|dx\\\leq \int _{{\text{supp }}\varphi }\|\varphi \|_{\infty }|f(x)|dx=\|\varphi \|_{\infty }\int _{{\text{supp }}\varphi }|f(x)|dx<\infty \end{aligned}}}

In order to have an absolute value strictly less than infinity, the first integral must have a well-defined value in the first place. Therefore,

T

f

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}}

R

{\displaystyle \mathbb {R} }

Continuity follows similarly due to

|

T

f

φ

l

−

T

f

φ

|

=

|

∫

K

(

φ

l

−

φ

)

(

x

)

f

(

x

)

d

x

|

≤

‖

φ

l

−

φ

‖

∞

∫

K

|

f

(

x

)

|

d

x

⏟

independent of

l

→

0

,

l

→

∞

{\displaystyle |T_{f}\varphi _{l}-T_{f}\varphi |=\left|\int _{K}(\varphi _{l}-\varphi )(x)f(x)dx\right|\leq \|\varphi _{l}-\varphi \|_{\infty }\underbrace {\int _{K}|f(x)|dx} _{{\text{independent of }}l}\to 0,l\to \infty }

, where

K

{\displaystyle K}

φ

l

,

l

∈

N

{\displaystyle \varphi _{l},l\in \mathbb {N} }

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi }

φ

l

,

l

∈

N

{\displaystyle \varphi _{l},l\in \mathbb {N} }

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

φ

{\displaystyle \varphi }

K

{\displaystyle K}

Linearity follows due to the linearity of the integral.

2.

We show that

T

f

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}}

f

∈

L

loc

1

(

O

)

{\displaystyle f\in L_{\text{loc}}^{1}(O)}

T

f

(

φ

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}(\varphi )}

φ

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \varphi \in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

f

∈

L

loc

1

(

O

)

{\displaystyle f\in L_{\text{loc}}^{1}(O)}

f

∈

L

loc

1

(

O

)

{\displaystyle f\in L_{\text{loc}}^{1}(O)}

T

f

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}}

D

∗

(

O

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {D}}^{*}(O)}

T

f

(

φ

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}(\varphi )}

φ

∈

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle \varphi \in {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

T

f

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {T}}_{f}}

D

(

O

)

{\displaystyle {\mathcal {D}}(O)}

Let

K

⊂

U

{\displaystyle K\subset U}

μ

:

K

→

R

,

μ

(

ξ

)

:=

inf

x

∈

R

d

∖

O

‖

ξ

−

x

‖

{\displaystyle \mu :K\to \mathbb {R} ,\mu (\xi ):=\inf _{x\in \mathbb {R} ^{d}\setminus O}\|\xi -x\|}

μ

{\displaystyle \mu }

1

{\displaystyle 1}

ξ

,

ι

∈

R

d

{\displaystyle \xi ,\iota \in \mathbb {R} ^{d}}

∀

(

x

,

y

)

∈

R

2

:

‖

ξ

−

x

‖

≤

‖

ξ

−

ι

‖

+