History of video games/Print version/Computer games

| This is the print version of History of video games You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

- Computer Gaming

Early Computer Games

[edit | edit source]See the chapters early games and Dr. Nim for early examples of computer games.

1970-1979

[edit | edit source]-

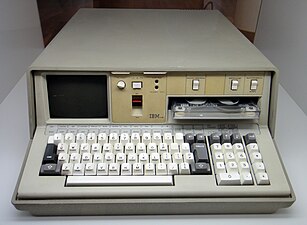

An IBM 5100 portable computer. While not used for gaming, it had a large influence on later designs.

-

Common computers released in 1977, the Commodore PET 2001, the Apple II, and the TRS-80 Model I.

-

An Ohio Scientific Challenger 2P

-

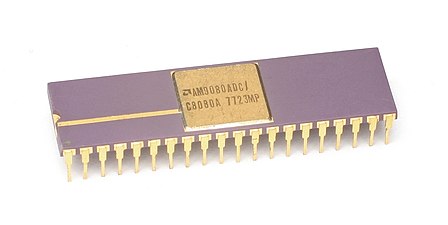

AMD 9080 Processor

Games

[edit | edit source]1980-1989

[edit | edit source]Notable Devices of the 1980's

[edit | edit source]CPUs

[edit | edit source]- 16 bit Intel 80286 (286) - 1982-1991

- 32 bit Intel 80386 (386) - 1985-2007

- 32 bit Intel 80486 (486) - 1989-2007

Regional Computers

[edit | edit source]In the 1980's there was a rivalry between Iraqi users of the Al Warkaa and the Sakhr 170 home gaming computers.[1][2]

In Wales, Dragon computers were popular.[3]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]-

ATI Hercules Graphics Card (1986)

-

AdLib Music Synthesizer Card (1987)

-

The Compaq Portable, a popular computer of the 1980's.

1990-1999

[edit | edit source]By 1990 well used dithering was being used in EGA games to create the illusion of better colors.[4] From the early to late 1990's Color Cycling, the shifting of a palette on a still image, was used to produce resource efficient animations in computer games.[4][5]

The 1990's saw the first common graphics cards, as well as the first common 3D API's for graphics cards such as Glide.

The introduction of CD-ROMs was initially seen as a way to reduce costs and piracy compared to floppy disks,[6] though pirates quickly gained familiarity with the new format.[7]

In 1994, the first Dreamhack was held in Malung, Sweden.[8]

In 1996 the Marine Doom is made for US military training, a notable early use of FPS games for military training.[9]

The Nvidia GeForce 256, considered as the world's first GPU, was released in 1999. It offered a huge improvement in 3D graphic capabilities.

-

The popularity of Doom was so massive that for a while first person shooters were commonly called "Doom clones"

-

The Quake engine spawned a number of decedent engines.

2000-2009

[edit | edit source]Valve launches Steam on September 12th, 2003.[10]

Audio Cards remain popular till the end of the decade in many high end gaming rigs, along with brief experiments in gaming themed network and physics acceleration cards.

Events

[edit | edit source]-

Dreamhack 2004 LAN party

-

PAX 2006 computer gaming.

-

A Korean PC Bang in 2006.

-

NVIDIA SLI at E3 2006

Components

[edit | edit source]-

GeForce FX5900

-

Powercolor Radeon 9000 AGP video card.

-

Nvidia 7900GS video card.

-

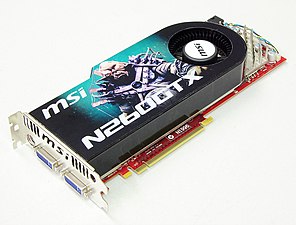

Nvidia 260 GTX. This card shows a trend where static 3D renderings were printed on the card.

-

A Turtle Beach Catalina sound card.

-

A Western Digital VelociRaptor in 2008.

-

A Linksys WRT54GS Router, common during the early to late 2000's.

-

2009 LCD shutter glasses for 3D gaming.

2010-2019

[edit | edit source]Rise of Steam

[edit | edit source]We think there is a fundamental misconception about piracy. Piracy is almost always a service problem and not a pricing problem. If a pirate offers a product anywhere in the world, 24 x 7, purchasable from the convenience of your personal computer, and the legal provider says the product is region-locked, will come to your country 3 months after the US release, and can only be purchased at a brick and mortar store, then the pirate's service is more valuable.

In 2011 Valve identifies game piracy as a service problem.[13] In 2013 Steam distributed 75% of digital games on PC.[14]

In 2015 Steam and Bethesda briefly introduced paid mods as a feature, before quickly withdrawing it in response to widespread criticism.[15][16]

Ray-tracing games started in 2018 and ray-tracing cards were released to be capable of ray-tracing in supported games. The first ray-tracing graphics cards were Nvidia RTX 2060, 2070, 2080, and Titan RTX.

2010's gallery

[edit | edit source]-

AMD booth at E3 2011

-

NVIDIA GTX 1070 Founders Edition

-

A Blizzard Battle.net Authenticator token in 2016.

2020-2029

[edit | edit source]The COVID-19 pandemic caused a shortage of computer parts.[17] Despite this the Folding@Home distributed computing project reaches quickly 1.5 Exaflops of capability as thousands of PC gamers donate unused cycles from their computers to tackle biomedical research in the fight against COVID-19.[18]

The Trump Administration began enforcing a new tariff on computer components from China near the end of it's term in mid January 2021, causing GPU prices to significantly increase, sometimes by several hundred dollars.[19][20]

Some manufactures experimented with PCs in handheld console formfactors.[21] In 2022 Steam released the Steam Deck, which is a handheld console that runs PC games.

In 2022 Intel released its first graphics cards: the Arc A750 and A770. These GPUs supported RTX 3060 performance for cheaper prices in games, especially DirectX 12 ones. DirectX 9 support was improved on these GPUs in 2023.

2020's gallery

[edit | edit source]-

Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090 Founders Edition

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "History of computers in Iraq". Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ↑ Byford, Sam (1 May 2012). "Al-Warkaa: the Iraqi home computer series that took on the MSX 'enemy'". The Verge. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ↑ Evans, Jason (23 December 2019). "When a Welsh computer was the must-have Christmas gift" (in en). WalesOnline. https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/dragon-computer-32-64-vintage-17433026.

- ↑ a b "8 Bit & '8 Bitish' Graphics-Outside the Box". Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Old School Color Cycling with HTML5 EffectGames.com". www.effectgames.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "WATCH OUT FOR THE CD-ROM HYPE Some industry executives tout the luminescent disks as the hottest thing since the VCR. But that view rests on seven myths you should know about. - September 19, 1994". archive.fortune.com. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ D'Alessio, Vittoria. "Chinese pirates target software on CD". New Scientist. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Dreamhack on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ↑ Riddell, Rob. "Doom Goes To War". Wired. https://www.wired.com/1997/04/ff-doom/.

- ↑ Sayer, Matt; Wilde, Tyler (12 September 2018). "The 15-year evolution of Steam". PC Gamer. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ↑ "Valve's Gabe Newell Says Piracy Is a Service Problem".

- ↑ "Gabe Says Piracy Isn't About Price - IGN".

- ↑ Cifaldi, Frank. "Valve: Piracy Is More About Convenience Than Price". Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ↑ "Valve Lines Up Console Partners in Challenge to Microsoft, Sony". Bloomberg.com. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ Prescott, Shaun (27 April 2015). "Valve has removed paid mods functionality from Steam Workshop". PC Gamer. https://www.pcgamer.com/valve-has-removed-paid-mods-functionality-from-steam-workshop/.

- ↑ McWhertor, Michael (27 April 2015). "Valve kills paid mods on Steam, will refund Skyrim mod buyers" (in en). Polygon. https://www.polygon.com/2015/4/27/8505883/valve-removing-paid-mods-from-steam.

- ↑ Leon, Nicholas De. "How to Buy a Computer During the Great Laptop Shortage of 2020". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Merritt, Rick (1 April 2020). "NVIDIA Blogs: Virus War Goes Viral: Folding@Home Gets 1.5 Exaflops to Fight COVID-19". The Official NVIDIA Blog. https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/2020/04/01/foldingathome-exaflop-coronavirus/.

- ↑ "With Tariffs Back in Place, GPU Vendors EVGA, Zotac Raise Prices on Graphics Cards" (in en). PCMAG. https://www.pcmag.com/news/with-tariffs-back-in-place-gpu-vendors-evga-zotac-raise-prices-on-graphics.

- ↑ Hollister, Sean (13 January 2021). "Sure enough, EVGA and Zotac have raised prices on the Nvidia RTX 3080 and beyond" (in en). The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/1/13/22228470/nvidia-evga-zotac-raise-prices-rtx-3080-3070-3060-3090.

- ↑ Palladino, Valentina (6 January 2020). "Dell’s new Concept UFO puts PC gaming on a Nintendo Switch-like device" (in en-us). Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2020/01/dells-new-concept-ufo-puts-pc-gaming-on-a-nintendo-switch-like-device/.

-

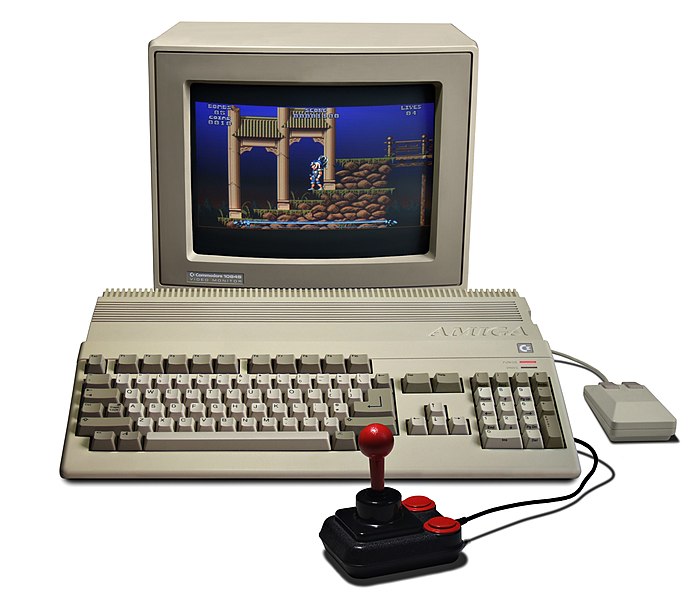

An Amiga 500 configured for games.

History

[edit | edit source]Launch

[edit | edit source]The Commodore Amiga 1000 was launched in 1985 for $1,295.[1]At the launch of the Amiga, artist Andy Warhol promoted the capabilities of the system for use in art.[2]

The cost reduced low end Amiga 500 followed in 1987.[3]

Use by creatives

[edit | edit source]Many game developer studios such as Psygnosis and Sensible Software got their start developing games for the Amiga.[4] To keep publishers updated before the proliferation of the internet, Amiga Developer Krister Karlsson recounted sending VHS tapes and floppy disks to his publisher in the mail.[5]

Other developers used the audio and graphical capabilities of the Amiga to develop games for other platforms. Junichi Masuda used an Amiga when creating the music for Pokémon Gold and Silver.[6]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Specs are for the Amiga 1000. Following models had different specs.

Compute

[edit | edit source]The Amiga 1000 is powered by the 16 bit Motorola 68000 clocked at 7.14 megahertz.[7][8]

The Amiga 1000 has 256 kilobytes of RAM by default.[8][7]

Software

[edit | edit source] |

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

Amiga computers ran the Amiga Workbench operating system, with Amiga Workbench 1.0 released in October 1985 with powerful multitasking and graphical capabilities.[9][10]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Comen, Evan. "Check out how much a computer cost the year you were born". USA TODAY. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ McCormick, Rich (24 April 2014). "Andy Warhol's Amiga computer art found 30 years later". The Verge. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Commodore Amiga 500 Personal Computer". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "I'll Never Love a Computer Like I Loved the Commodore Amiga". www.vice.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Making a game in 1993". www.gamasutra.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "HIDDEN POWER of masuda". web.archive.org. 23 November 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Commodore Amiga 1000 computer". oldcomputers.net. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "History of AmigaOS". AmigaOS. 28 May 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "AmigaOS far ahead of its contemporaries from 1985 until 1990". GenerationAmiga.com. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

-

The Amstrad CPC464 computer.

History

[edit | edit source]

The Amstrad CPC 464 was launched on April 12, 1984.[1]

CPC is short for Colour Personal Computer.[1]

Over two million CPC computers were sold, with high popularity in continental western Europe.[2][3]

Technology

[edit | edit source] |

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

The CPC 464 is powered by an 8-bit Zilog Z80 processor clocked at four megahertz.[4]

The system has 64 kilobytes of RAM, with 42 kilobytes being available to the user.[5]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]-

3 inch floppy disks used by Amstrad.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b Smith, Tony. "You're NOT fired: The story of Amstrad's amazing CPC 464". www.theregister.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Amstrad CPC 464 - Computer - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Amstrad CPC 464 Retro Gamer". www.retrogamer.net. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Smith, Tony. "You're NOT fired: The story of Amstrad's amazing CPC 464". www.theregister.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

-

An Apple II with 1977 accessories attached, including game pads.

History

[edit | edit source]The Apple II was launched in April 1977.[1]

The Apple II was discontinued in 1993,[2] having been a critical platform in the Computer market, and by extension the computer gaming market, for well over a decade and a half.

Around 2017 a massive effort was made to preserve as much Apple II software as possible, before media degradation made some software lost to history.[3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]These specs are for the original Apple II. Later models offered enhanced capabilities.[4]

Compute

[edit | edit source]The Apple II is powered by an 6502 processor clocked at 1 megahertz.[5]

The Apple II originally shipped with 4 kilobytes of RAM, and could be expanded to 48 kilobytes.[5]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The Apple II shipped with an 8 kilobyte ROM.[5]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Apple II Personal Computer". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Contributor, Minda Zetlin (23 January 2020). "These old Apple computers are worth up to $905,000—and you might have one sitting in your basement". CNBC. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Programmers Are Racing to Save Apple II Software Before It Goes Extinct" (in en). www.vice.com. https://www.vice.com/en/article/gv39mx/programmers-are-racing-to-save-apple-ii-software-before-it-goes-extinct.

- ↑ "Today in Apple history: The final Apple II model arrives". Cult of Mac. 15 September 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Apple II advertisement". Retrieved 28 November 2020.

History

[edit | edit source]The Atari 800 and 400 were released in 1979 with the 400 costing $550 and the 800 costing $1000.[1]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The Atari 400 and the Atari 800 are powered by an 8-bit 6502 processor clocked at 1.79 megahertz.[2][3]

The Atari 400 has eight kilobytes of RAM in early models and 16 kilobytes of RAM in later models.[4] The Atari 800 has 16 kilobytes of RAM in early models and 48 kilobytes of RAM in later models.[5]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Atari 400

[edit | edit source]Atari 800

[edit | edit source]Accessories

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Inside the Atari 800". PCWorld. 4 November 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "A History of Gaming Platforms: Atari 8-Bit Computers". www.gamasutra.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "A History of Gaming Platforms: Atari 8-Bit Computers". www.gamasutra.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

-

A BBC Micro computer.

History

[edit | edit source]The BBC Micro was launched in December 1981.[1]

The BBC Micro is sometimes nicknamed the Beeb.[2]

The BBC Micro was discontinued in 1994.[1]

BBC Micro developer Acorn Computers would later develop the ARM architecture,[3] which would later be used by a number of gaming systems.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The BBC Micro is powered by an 8-bit MOS 6502 processor.[3][4]

The BBC Micro has 32 kilobytes of RAM.[3]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b Jakobsen, Remi (23 November 2019). "BBC Micro Model B". Remi's Classic Computers. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "The BBC Computer Literacy Project - The BBC Micro (1981)". cybercemetery.unt.edu. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "DEVELOPMENT OF THE ARM CHIP AT ACORN". www.cs.umd.edu. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Chip Collection - Synertek, Inc. Donation, Smithsonian Institution". smithsonianchips.si.edu. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

History

[edit | edit source]The Classic Mac operating systems are considered to be releases from System 1 in 1984 to System 9 in 1999.[1][2]

Despite Apple's troubles during the run of the Classic Mac OS, the Classic Mac OS did see some games released for it.[3][4]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]1989

[edit | edit source]Caper in the Castro

[edit | edit source]A 1989 point and click hypercard game for MacOS which was among the first video games to feature a significant plot focused on LGBTQ subject matter.[5]

1993

[edit | edit source]Pathways into Darkness

[edit | edit source]A first person action adventure game by Bungie.

Read more about Pathways into Darkness on Wikipedia.

1994

[edit | edit source]Emora Kart

[edit | edit source]An early clone of the then recently released Super Famicom and Super Nintendo Entertainment System game Mario Kart.[6][7][8]

Marathon

[edit | edit source]The first game in the Marathon trilogy of sci-fi first person shooters by Bungie.

Read more about Marathon on Wikipedia.

1995

[edit | edit source]Marathon 2: Durandal

[edit | edit source]The second game in the Marathon trilogy of sci-fi first person shooters by Bungie.

Read more about Marathon 2: Durandal on Wikipedia.

1996

[edit | edit source]Marathon Infinity

[edit | edit source]The final game in the Marathon trilogy by Bungie.

Read more about Marathon Infinity on Wikipedia.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Biersdorfer, J. D. (14 September 2000). "Apple Breaks The Mold (Published 2000)". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "October 23, 1999: Mac OS 9 Released - AppleMatters". www.applematters.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Editorial: Will Apple's 1990's "Golden Age" collapse repeat itself?". AppleInsider. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Staff, Ars (11 September 2016). "An OS 9 odyssey: Why these Mac users won't abandon 16-year-old software". Ars Technica. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "You Can Now Play the First LGBTQ Computer Game, For the First Time" (in en). www.vice.com. https://www.vice.com/en/article/ne4nzz/play-the-first-lgbtq-computer-game-for-the-first-time-caper-in-the-castro.

- ↑ "Random: Check Out Emora Kart, A Macintosh-Exclusive Super Mario Kart Clone From 1994". Nintendo Life. 3 November 2021. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2021/11/random-check-out-emora-kart-a-macintosh-exclusive-super-mario-kart-clone-from-1994.

- ↑ "Mouse-controlled Super Mario Kart clone for classic Macintosh ⌘I Get Info". blog.gingerbeardman.com. https://blog.gingerbeardman.com/2021/10/31/mouse-controlled-super-mario-kart-clone-for-classic-macintosh/.

- ↑ "えもらのカート (Emora Kart)". June 1994. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

-

A recreation of a typical Commodore 64 gaming scene in the 1980's.

History

[edit | edit source]The Commodore 64 was introduced in 1982 for $595, a price considered low given it's specs and enabled by Commodore's in house manufacturing.[1][2] The manufacturing price of each commodore 64 was about $135[3] giving Commodore about a $460 margin before shipping, advertising, and other costs are considered.

In time, the price of the Commodore 64 would drop to $200 and the manufacturing costs of the Commodore 64 would drop to $25.[4]

The Commodore 64 was discontinued in 1994, with 17 million Commodore 64 computers sold.[1][2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The Commodore 64 is powered by the 8-bit MOS Technology 6510 CPU, clocked at 1.023 megahertz in NTSC regions or 0.985 megahertz in PAL regions.[5]

The Commodore 64 has 64 kilobytes of RAM.[4]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The Commodore 64 can generate three channels of audio via a SID 6581 chip.[4]

Media

[edit | edit source]The only type of media that the Commodore 64 accepts without needing external peripherals are ROM cartridges. Cartridges were mostly used for video games and programming languages, but later also saw (and continue to see) usage for hardware enhancement.

The system was compatible with the Commodore Datasette tape drive, on which many users relied to load software, both retail, pirate or simply custom-written.

Much of the software was also distributed on 5¼-inches floppy disks to be read by Commodore 1541 or compatible drives, connected to the system through its "Commodore" bus. Similarly to previous Commodore disk drives, the 1541s worked like computers on their own, running Commodore DOS to load and save data, as well as interacting with the C64.

Notable Games

[edit | edit source]1987

[edit | edit source]- Bad Street Brawler / Street Hassle - A beat up up released on multiple platforms. An early example of a game which allowed players to pet dogs.[6]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Commodore 64

[edit | edit source]Audio output

[edit | edit source]- This is an example of the Audio capabilities of the SID 6581 chip.

- This is an example of Automatic Mouth speech synthesis output from a Commodore 64.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b "Impact of the Commodore 64 : a 25th anniversary celebration, lecture by Adam Chowaniec et al. Computer History Museum". www.computerhistory.org. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Commodore 64 - The Most Popular Retro Computer of All Time". Adafruit Learning System. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Commodore 64 - History of the Commodore 64 Computer". history-computer.com. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Commodore 64 computer". oldcomputers.net. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Commodore 64 - Angry Video Game Nerd (AVGN)". Retrieved 3 October 2021.

History

[edit | edit source]Dr. Nim was a mechanical consumer computed dedicated to playing a single computer game released in the 1960's.[1]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Dr. Nim can play against a human opponent, or it can play against itself.[1] Dr. Nim also had a difficulty setting between perfect play which was between un-winnable without cheating, and winnable.[2]

Dr. Nim uses a special board and 18 marbles for operation.[3]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b "The Alan Kaminsky Museum of Antique Computing Devices". www.cs.rit.edu. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ "Ryan's Blog: Beat Dr. Nim! (Part 1)". Ryan's Blog. 7 July 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Amazing Dr. Nim board game 102688881 Computer History Museum". www.computerhistory.org. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

-

The FM Towns

-

Two models of the FM Towns II.

History

[edit | edit source]

The FM Towns was a Fujitsu computer that excelled at gaming and released in Japan in February 1989 for 338,000 yen.[1][2]

The Towns part of the name is said to be a reference to Charles Hard Townes, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1964.[2][3] As Charles Hard Townes invented the laser[4] , the name is perhaps appropriate for the CD-ROM based computer, which uses a laser to read optical media.

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The FM Towns is powered by a 32 bit Intel 80386dx processor clocked at 16 megahertz, with a 80387 coprocessor.[2]

The FM Towns contained between 1 and 6 megabytes of RAM depending on the configuration.[1]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The FM Towns contained a built in CD-ROM drive standard.[1]

Software

[edit | edit source]The FM Towns ran the custom Towns OS made by Fujitsu.[1]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d "FM TOWNS (1989) - Fujitsu Global". www.fujitsu.com. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ "Charles H. Townes Facts". Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ "Nobel laureate and laser inventor Charles Townes dies at 99". Retrieved 25 November 2020.

-

An IBM 5150 Personal Computer.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]The IBM 5100 of 1975 was the first minicomputer made by IBM.[1] APL models of the 5100 could essentially emulate a IBM System 360 mainframe.[1]

The accelerate development the IBM PC was developed in the span of 12 months by extensively using components made by other companies.[2]

Launch

[edit | edit source]A press release by IBM in late August 1981 touts the capabilities of the IBM 5150, including a brief mention that the system can be used to easily play video games.[3]

The IBM 5150 was released in September of 1981 at a base cost of around $1,565, a home use setup costing around $3005, and a business system costing around $4,500.[4][3] Because the only thing IBM actually made for the IBM PC was the BIOS, clones of the system existed within a year, though were quickly stopped by legal action.[5] Compaq made a clone with a legally engineered compatible BIOS, paving the way for other clones to create the modern PC platform.[6][7]

Technology

[edit | edit source]There are many iterations of the IBM Personal Computer. This section covers the IBM 5150 model.

An 16-bit x86 architecture Intel 8088 CPU clocked at 4.77 megahertz powers the IBM 5150.[4] The IBM 5150 came with 16 kilobytes of RAM standard, and could be configured with up to 256 kilobytes of RAM.[8] The IBM 5150 shipped with 40 kilobytes of ROM.[8]

The only custom part was the BIOS chip. As mentioned earlier, once that was reverse engineered using clean room techniques, many legal clone machines were brought to the market.[9] These clones were often cheaper or sported features the official IBM PC models lacked.[10]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]IBM 5150

[edit | edit source]Related IBM Computers

[edit | edit source]Compaq Portable

[edit | edit source]Ad-Lib sound output

[edit | edit source]- An example music file similar to what would run on real Ad-Lib hardware. Note that the IBM PC did not originally ship with this hardware.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b "IBM 5100 computer". oldcomputers.net. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "IBM Archives: The birth of the IBM PC". www.ibm.com. 23 January 2003. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "IBM Archives: Announcement press release". www.ibm.com. 23 January 2003. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "IBM 5150 Personal Computer". oldcomputers.net. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Send in the Clones - CHM Revolution". www.computerhistory.org. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Tales from 80s Tech: How Compaq's Clone Computers Skirted IBM's IP and Gave Rise to EISA - News". www.allaboutcircuits.com. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "The IBM Compatible or Clone - History of the Progression of Computer Technology - Electronic Tutorials and Circuits". www.hobbyprojects.com. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "IBM Archives: Product fact sheet". www.ibm.com. 23 January 2003. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Send in the Clones - CHM Revolution". www.computerhistory.org. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ↑ Haigh, Thomas. "The IBM PC: From Beige Box to Industry Standard". cacm.acm.org. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

-

A Sony HitBit HB-10P MSX computer.

History

[edit | edit source]Launch

[edit | edit source]The MSX computer standard was announced in 1983 to promote compatibility between computers.[1] The MSX standard was regionally popular in Japan and also in Brazil.[2]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Over five million MSX computers were sold.[3]

A Sony HB-G900 MSX2 computer and HBI-G900 videotizer was used on the MIR space station.[4][5]

Technology

[edit | edit source]MSX1 spec

[edit | edit source]MSX1 computers use 8-bit Z80A processors clocked at 3.58 megahertz.[6] Permitted video coprocessors include the TMS 9918/A, TMS 9928/A, or TMS 9929/A.[6]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Loguidice, Bill (14 April 2017). "The bright life of the MSX, Japan's underdog PC". PC Gamer. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "MSX History: The Platform Microsoft Forgot". Tedium: The Dull Side of the Internet. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "10 Most Popular Computers in History". HowStuffWorks. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "MSX IN SPAAAACCCEE". msx.gnu-linux.net. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

-

An NEC PC-8801 computer with a SonySony KV-1311CR Trinitron Monitor.

History

[edit | edit source]Launch

[edit | edit source]NEC launched the PC-8800 line in 1981.[1] The system would quickly become a mainstay in Japanese home computer gaming.

Use by creatives

[edit | edit source]The PC88 was a popular platform for Japanese indie game developers during the 1980's.[2]

Composer Yuzo Koshiro often used the PC-88 when developing music for console games, actively using the system for commercial title development as recently as 2016 with his work on Etrian Odyssey V.[2][3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The technical attributes of the system resulted games for the system possessing a unique aesthetic.[2]

Games

[edit | edit source]Super Mario Bros. Special

[edit | edit source]An infamously poor yet official port of Super Mario Bros for the computer.[2][1][4]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Read More

[edit | edit source]- The Wikibook NEC PC Programmers Reference has information on programing NEC computers, including the PC88 series.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b "The 20 greatest home computers – ranked!" (in en). the Guardian. 7 September 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/games/2020/sep/07/the-20-greatest-home-computers-ranked.

- ↑ a b c d e f g "Gaming computers of Japan: The NEC PC-8800 series" (in en). Retronauts. https://retronauts.com/article/342/gaming-computers-of-japan-the-nec-pc-8800-series.

- ↑ Faulkner, Cameron (24 February 2021). "Watch composer Yuzo Koshiro play his iconic chiptunes through an NEC PC-88" (in en). The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/tldr/2021/2/24/22299391/yuzo-koshiro-nec-pc88-pc-streets-of-rage-sonic-music.

- ↑ "Let’s remember Nintendo’s official – and terrible – Mario PC games". PCGamesN. https://www.pcgamesn.com/terrible-mario.

-

An 1981 Texas Instruments 99/4A computer with two joysticks attached.

History

[edit | edit source]

The Texas Instruments TI-99/4 was released in 1979 at a cost of $1,150.[1][2]

The improved Texas Instruments TI-99/4A was released in June 1981 at a cost of $525.[1][3]

Despite costing less than $100 by fall of 1982, and by being promoted by then popular comedian Bill Cosby, the TI-99/4A was severely challenged in the market by fierce competition in the low end segment, and by the video game crash of 1983.[2]

Production of the Texas Instruments TI-99/4A ended in 1984 with about 2.5 million systems sold.[4][5]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The Texas Instruments TI-99/4A is powered by the 16-bit TMS9900 processor clocked at three megahertz.[3]

A TMS 9918 or TMS 9929 handles video processing.[4]

The TI-99/4A has 16 kilobytes of RAM and 16 kilobytes of video RAM.[3][4]

Hardware

[edit | edit source] |

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

The TI-99/4A has 26 kilobytes of ROM.[3]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]360 View

[edit | edit source]Details

[edit | edit source]Accessories

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b "Full Page Reload". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b Pollack, Andrew (19 June 1983). "THE COMING CRISIS IN HOME COMPUTERS (Published 1983)". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d "Texas Instruments TI-99/4A computer". oldcomputers.net. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Texas Instruments Model 994A Personal Computer". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

History

[edit | edit source]Like previous versions of Windows, Windows 95 and 98 were based on MS-DOS.[1][2][3] However unlike previous versions, starting with Windows 95 DOS became integrated with MS-DOS, rather then a separate product running on top of it.[3] Windows 95 also introduced DirectX, an API that allowed game developers to avoid direct access to hardware.[4] Windows 98 offered improvements related to networking.[5]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]- Wolfenstein 3D

- Doom

- Quake

- Duke Nukem 3D

- Myst

- Lionel Trains Presents Trans-Con!

- RollerCoaster Tycoon

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Computers

[edit | edit source]Audio

[edit | edit source]- An example of MIDI music, a common choice for game music on Windows PCs at the time.

Technology

[edit | edit source]Computer components

[edit | edit source]CPUs

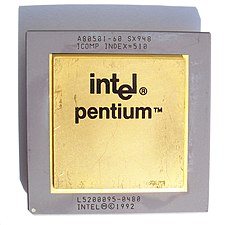

[edit | edit source]- 32-bit Pentium - (1993-2000)

- 32-bit AMD K5 - (1996)

- 32-bit Pentium II - (1997-2003)

- 32-bit AMD K6 - (1997)

- 32-bit Athlon Classic - (1999)

-

Pentium 60 SX948

-

AMD 386DX

-

UMC Intel compatible 40MHz Green CPU.

-

CPU Cyrix 486DRx²

Expansion cards

[edit | edit source]-

Diamond Monster3D Voodoo 1 Graphics Card

-

A GeForce 256

-

SoundBlaster Pro, a common sound card of the era.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "What was the role of MS-DOS in Windows 95?". The Old New Thing. 24 December 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Speed, Richard. "Happy birthday, you lumbering MS-DOS-based mess: Windows 98 turns 20 today". www.theregister.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b Manes, Stephen (1 August 1995). "PERSONAL COMPUTERS; Personal Computers: What Is Windows 95 Really Like? (Published 1995)". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "The History of DirectX » CodingUnit Programming Tutorials". Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Lewis, Peter H. (30 April 1998). "Windows 98, The Tuneup (Published 1998)". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

-

A 48k ZX Spectrum computer.

History

[edit | edit source]

Launch

[edit | edit source]The ZX Spectrum was launched in 1982.[1]

A number of Spectrum focused periodicals were in print.[2]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]In 1992 the ZX Spectrum was discontinued with five million systems sold.[3][4]

Sir Clive Sinclair passed away in London on Thursday, September 16th, 2021.[5]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The ZX Spectrum is powered by an 8-bit Z80A processor clocked at 3.5 megahertz.[3][6]

Depending on the model the ZX Spectrum has either 16 kilobytes of RAM or 48 kilobytes of RAM.[3]

Hardware

[edit | edit source]The ZX Spectrum has 16 kilobytes of RAM.[3]

The unintentional "Colour Clash" effect of the ZX Spectrum created a unique aesthetic for games on the system.[7]

Games

[edit | edit source]1985

[edit | edit source]Don't Buy This

[edit | edit source]An early game compilation of poor quality games.

Read more about Don't Buy This on Wikipedia.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Notes

[edit | edit source]Naming

[edit | edit source]Being primarily used in the UK, the name is pronounced as "Zed" X Spectrum.[8] The system was sometimes known by the nickname "Speccy".[9]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Sinclair ZX Spectrum 48k - Computer - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Spectrum wasn’t just a computer - it was a family" (in en-gb). Eurogamer.net. 17 April 2022. https://www.eurogamer.net/the-spectrum-wasnt-just-a-computer-it-was-a-family.

- ↑ a b c d "How the Spectrum began a revolution". 23 April 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "ZX Spectrum: 30 years old, and still one of the cheapest computers ever made - ExtremeTech". www.extremetech.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Sir Clive Sinclair: Computing pioneer dies aged 81". BBC News. 16 September 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-58587521.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Colour Clash: The Engineering Miracle of the Sinclair ZX Spectrum". Paleotronic Magazine. 29 September 2018. https://paleotronic.com/2018/09/29/loading-ready-run-sinclair-edition-the-zx-spectrum/.

- ↑ "ZX Spectrum Vega Review // Sent In For Review - Rerez". Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ↑ Lyons, Kim (18 September 2021). "Clive Sinclair, inventor of the ZX Spectrum personal computer, has died" (in en). The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/9/18/22680955/clive-sinclair-home-computers-electric-vehicle-calculator.