Transportation Systems Casebook/Printable version

| This is the print version of Transportation Systems Casebook You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Transportation_Systems_Casebook

Introduction

This Casebook contains a set of case studies developed by students enrolled in the Introduction to Transportation Systems course taught in the School of Policy, Government and International Affairs at George Mason University by Prof. Jonathan Gifford.

About

The following should be included the written Case Study Report:

- Summary

- Annotated List of Actors

- Timeline of Events

- Maps of Locations

- Clear Identification of Policy Issues

- Narrative of the Case

- Discussion Questions

- Complete References of Cited (primary and secondary) Documents (with hyperlinks as appropriate)

The report should be written from a Neutral Point-of-View. Online encyclopedias are not acceptable sources for citation (feel free to read to get background information, but they are at best tertiary sources).

The report should be on the order of 3000-5000 words. It should be fully referenced. Additional readings on the order of 30 -100 pages should be assigned with the case, these will be linked on the case web page or handed out in class.

Source: Adapted from "Transportation PlanningCasebook/About, " Wikibooks , accessed Sep 2014

China’s Belt and Road

Summary

[edit | edit source]The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a cross-regional infrastructural initiative unveiled by China in 2013. It has since had global commentary both positive and negative and sparked criticism and support from various political regimes. It is currently as controversial as it is ambitious. Currently, China has spent an estimated $200 billion with Morgan Stanley estimating that by 2027 China would have spent between $1.2- $1.3 trillion on the BRI.[1] China plans to complete this multi-billion dollar initiative in 2049.

Annotated List of Actors

[edit | edit source]· Hillary. R. Clinton, U.S. Secretary of State (2009-2013)

· Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and President of China

· Central Committee (of the Chinese Communist Party wrote the comprehensive reform blueprint of the Initiative in November 2013).

· State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (The chief administrative authority of China)

· National Development and Reform Commission. (NDRC)

· Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (China)

· Ministry of Commerce. (China)

· Asian Infrastructure Development Bank (AIIB), China-ASEAN Maritime Cooperation Fund, China-Indonesia Maritime Cooperation Fund and Silk Road Fund. These financial institutions lend out loans for infrastructure projects on BRI mostly in the Asia-Pacific region.

· ASEAN. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations is a regional intergovernmental organization of the member countries that promotes and facilitates economic, political, security, military, educational, and sociocultural integration among its members.

· Participating countries and international organizations.

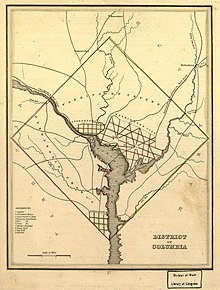

Maps of Locations

[edit | edit source]

Timeline of Events

[edit | edit source]- Initiative unveiled in September and October of 2013 by Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

- Blueprint of the Initiative was made by the Central Committee with the approval of the State Council in November 2013.

- In March 2015, detailed plans of the BRI were laid out by the National Development Reform Commission (NDRC), Foreign Affairs Ministry and Ministry of Commerce.

- Asian Infrastructure Development Bank although established in 2013 began its operation in December 2015.

- The first and inaugural forum on the Belt and Road Initiative was held in May 2017.

- October 2017, the BRI is added to the Chinese Communist Party’s constitution.

- Second forum on the BRI was held in April 2019.

Clear Identification of Policy Issues

[edit | edit source]The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative foster regional, economic and international development for about 64% of the World’s population. This initiative has the following:

Pros:

[edit | edit source]- Fosters economic development and integration resulting in growth to both developed and developing countries.[1] This initiative seeks to make this integration a win-win cooperation and prosperity for all.

- Improving upon and influencing current international economic system reforms and architecture.[2] Having had slow and difficult international economic reforms in decades, China on becoming an emerging power seeks to play an important role in shaping the global economic system.

- Provides hard infrastructure in the form of roads, railways, pipelines ports and others which will lead to a reduction in transportation time and other costs associated with trade.[3] The creation of the infrastructure will help countries export their products easily to other countries leading to such benefits as earning of foreign currencies, creation of jobs and increased market shares of goods and services.

Cons:

[edit | edit source]- Although not fully executed, the BRI faces certain challenges, criticisms and oppositions. Some of the major challenges of the BRI stems from the risk associated with how broad and ambitious the BRI is and also based on political values of participating countries as against that of the Chinese. Some of these challenges, criticisms and opposition include:

- Lack of information and transparency of BRI investments. Some of the BRI investments have the requirement that they can only be awarded and undertaken by Chinese contractors. Contractors use this requirement as a basis to not disclose information which allows them the opportunity to inflate the costs of infrastructure. This has led to over-inflated cost and increase debts on the part of borrowing countries partaking in the building of infrastructure. This has then led to mistrust and opposition and even withdrawal from the BRI in some countries.[4]

- The BRI is considered as neocolonialism or a ploy by China to dominate Asia and trade. Given the low-interest loan rates accessible to participating countries in developing the infrastructure for the BRI, critics see this as a way of China creating unsustainable debt burdens for its neighbors and potentially taking control of regional choke points.

- Excess exports by China are another sign that raises questions and criticisms on the dominance of China on trade. Some Chinese experts are of the view that one of the benefits of the BRI investments is to be able to absorb China’s excess capacity which although true could create unfavorable trading terms for other countries. India is one of the countries that see China as using such a ploy.[5]

- The risk of clashes of political values and culture across countries. Since the BRI has a broad and rich mix of political regimes and economic systems such as capitalism, socialism and others, there are bound to be challenges in cooperation and coordination among countries, which may result in delays in the execution of projects. [6]

- Difficulty in achieving financial sustainability of cross-country projects. To be able to sustain these cross-country infrastructure projects, the return on investment should outweigh the cost. Most Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) undertaken by the Chinese government and companies have not been profitable. This shows that China does not have lot of favorable outcomes running cross-border projects which makes the profits to be derived from the BRI questionable.[7]

Narrative of the Case

From ancient Silk Road to the Belt and Road Initiative: a historic perspective of transcontinental trade in Eurasia.

The human being has historically been in search of more favorable conditions to live in. This desire has been driving him to explore new destinations and open new routes.

The emergence of cross-continental trade networks in the Eurasian continent date back to the period of the Han Dynasty in China, when the unique Chinese merchandise like silk and spices reached Europe. Trade in silk and related byproducts in the broader Eurasian continent opened small-size trade linkages between and among the regional commercial hubs in the Central Eurasia, and stimulated the growth of medieval cities like Samarkand, Bukhara, Aleppo etc. These small trade linkages emerged into major trade routes connecting China to European markets as transcontinental trade began to evolve. Historians named the network of commercial trade routes connecting China to Europe as the “Silk Road”.

Transcontinental trade between China and Europe was flourishing until Constantinople – the capital city of Byzantine Empire and the major trade hub on the crossroads of Europe and Asia, fell to Ottoman Empire in 1453. Constantinople’s fall dramatically changed the geopolitics in the broader Eurasian continent and stimulated the European explorations of alternative trade routes to China.[1]

Although, the commerce in the city re-established following the conquest and Istanbul[2] regained its dominance over transcontinental trade routes shortly, overland trading eclipsed by the exploration of new maritime routes.[3] Improvement in technology which could support long maritime journeys, as well as significant scientific changes about the understanding of the World in late fifteenth century would encourage the Europeans to find new ways for trade with China, avoiding trade middlemen of Central Asia and then less friendly Turkish control of the overland trade routes.

Throughout the history wars and geopolitics significantly shaped and reshaped the Eurasian transcontinental trade routes on micro and macro levels. Decline of the overland trade via Silk Road had mirrored onto the development of the trade hubs in Eastern China, Central Asia and Caucasus. Only in eighteenth century the Silk Road region regained its strategic importance as it had become the intersection of three major geopolitical powers-Russian, British and Chinese empires – now mostly from cultural and archeological point of view.[4]

Establishment of Russian dominance over the Central Eurasian region and the Caucasus in early nineteenth century and emergence of the Soviet Union in 1920s significantly affected the flow of people and goods through the Silk Road.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 opened unique opportunities for the regional trade, integration and re-emergence of the ancient Silk Road, as this region become attractive again for foreign investments. In 1993, the European Union introduced the “Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia” (TRACECA) program to develop transport corridor from Europe to China, via the Black Sea, the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea and Central Asia.[5] Central Asia and the Caucasus has significantly enjoyed the Western political and economic support until recently. On July 20, 2011, in Chennai, India, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary R. Clinton laid out the United States’ vision of the new Silk Road and the U.S. support to re-establishing the “international web and network of economic and transit connections” in Eurasia. The U.S. policy concerning the trade and transit connections in the Central Eurasia would later be dubbed as the New Silk Road Initiative.[6]

In 2013, in the light of the NATO’s (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) gradual withdrawal from Afghanistan, as well as the U.S.’ active engagement with the Central and South Asian countries to forge the regional integration, China introduced the “Belt and Road Initiative” – a new transcontinental integration policy which would stimulate closer economic ties and deepen cooperation in the greater Eurasian region – but this time, under Chinese dominance.

Belt and Road Initiative as an economic tool for the integration of regional economies

Officially, the BRI was introduced by the Paramount leader of the People's Republic of China Xi Jinping during his visits to Kazakhstan in September 2013 and to Indonesia in October 2013. The multi-billion dollars initiative which covers 71 regional economies, including China involves two major components: Silk Road Economic Belt and the New Maritime Silk Road.

In his speech at the Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan, Chinese leader Xi Jinping proposed a new integration policy to improve the transcontinental connectivity and cooperation by building “economic belt along the Silk Road” which would span from the Pacific to the Baltic Sea.[7]

A month later, Chinese leader Xi Jinping during his speech before the Indonesian Parliament introduced the New Maritime Silk Road Initiative, which envisages strengthening the China-ASEAN maritime cooperation and investments through the China-led China-ASEAN Maritime Cooperation Fund and China-Indonesia Cooperation Fund.[8]

For the implementation of this initiative China has signed intergovernmental agreements and memorandums of understanding with number of countries trying to bind the economies to the emerging transcontinental network. However, the BRI geography still remains debatable due to lack of integrated transportation linkages, disparity in regional economic development and huge cost burden that the initiative can put over smaller economies.

According to the RAND Corporation report, poor development of overland transportation networks, particularly rail connection between neighboring countries significantly affects the regional trade. Rail connection and harmonization of border-crossing processes are of the greatest importance for the trade facilitation in the Central Eurasian region as the 25% of BRI countries in this region are landlocked, thus are heavily depended on the rail communication. The RAND Corporation estimates with regard to the correlation of rail connection to the level of trade in the BRI region show that adding rail connection between trading partners increases trade by 2.8 per cent in average (Table 1).[9]

Table 1. Sensitivity test of the impact of transport connectivity on export trade volumes

| Change of transport indices | Change in trade |

| Added rail connection | 2.8 per cent |

| Air distance reduced by 10 per cent | 0.41 per cent |

| Maritime distance reduced by 10 per cent | 0.13 per cent |

Source: RAND Corporation

From economic point of view, experts argue that if fully implemented, the BRI can reduce travel time for transcontinental delivery of goods and stimulate foreign investments to the regional economies. With proposed level of investment and improved regional trade relations between and among the regional countries, the BRI’s realization would not only affect the level of trade in the BRI region but also would have impact on the non-BRI markets. According to the World Bank report (2019), if fully executed the BRI transport infrastructure can reduce travel time by up to 12 per cent and increase world trade between 1.7 and 6.2 per cent.[10]

The multibillion dollar initiative is heavily dependent on the Chinese investments. It is funded through different China-led programs and financial institutions, most importantly Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, China-ASEAN Maritime Cooperation Fund, China-Indonesia Cooperation Fund and the Silk Road Bank. Although most of the popular sources indicate that Chinese investments for the BRI projects is from $1 trillion -$8 trillion, the World Bank estimates that the overall BRI investments do not exceed $575 billion.[11]

According to the World Bank statistics, the BRI financing is rapidly increasing public and corporate debt in emerging markets, which have already reached the historic pick since 1980s.[12] In this circumstances, increasing debt burden in less developed economies create challenges for sovereign debt sustainability and make them vulnerable to debt distresses. The Center for Global Development has identified 23 BRI economies relevantly susceptible to the raising debt burden. Eight of them are of particular concern: Djibouti, the Kyrgyz Republic, Lao’s People’s Democratic Republic, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan and Tajikistan.[13]

Belt and Road as the foreign policy tool

In 2017, the 19th National Party Congress of the China’s Communist Party formally incorporated the Belt and Road Initiative into the Chinese Constitution by writing the following wording into it: “[] following the principle of achieving shared growth through discussion and collaboration, and pursuing the Belt and Road Initiative.”[14] This was significant adjustment into the BRI, as it now represents the Government’s policy rather than Chinese overseas investment program.

Although China’s BRI project has widely been seen mostly in economic terms, it has always had strategic meaning for the Chinese Government. The BRI policy identifies five major elements for the transcontinental integration: policy communication among regional countries; hardware improvement; trade facilitation; monetary policy; and people-to-people contacts.[15] Almost all these elements hold national security importance for China.

Experts assert that by investing in BRI Chinese Government aims to stabilize border regions by mitigating threats time-to-time emanating from peripheries; securing energy supply and transport routes by establishing overland oil transportation systems; and the last but least to cultivate stronger diplomatic and economic influence in the region by signing partnership agreements and memorandums of understanding and investing in the development of regional economies.[16]

Effective implementation of the BRI in a broader perspective is shaped by the expectations and reactions of the major World powers, like the United States and the European Union. Although the U.S. Government in many occasions voices that the U.S.’ New Silk Road Initiative and BRI are complementing each other, the trade confrontations between the two, as well as increasing Chinese influence over the regions once dominated by the western investments can prove the opposite. During the hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Secretary James Mattis commented on the BRI in a following way:[17]

Regarding 'One Belt, One Road,' I think in a globalized world, there are many belts and many roads, and no one nation should put itself into a position of dictating 'One Belt, One Road.' That said, the 'One Belt, One Road' also goes through disputed territory, and I think that in itself shows the vulnerability of trying to establish that sort of a dictate.

Another factor that makes the BRI an issue of the national security for China is the security and safety concerns associated with Chinese business involvement in remote and unstable areas like Africa, Middle East and Central Asia. These threats include but not limited to examples as anti-Chinese sentiments in Yemen – deportation of 500 Chinese nationals from Yemen; killing of Chinese citizens in Syria in 2015 and in Pakistan in 2017 etc.[18]

The withdrawal of NATO and U.S. forces from Afghanistan and U.S. distancing from Central Eurasian affairs in recent years have created a geopolitical vacuum in Central Eurasian which has become more susceptible to the increasing Chinese influence, most importantly through the Belt and Road Initiative.

Lessons Learned / Takeaways

[edit | edit source]· The BRI now a part of the Constitution of the Communist Party of China represents the Government’s policy rather than Chinese overseas investment program.

· Although China’s BRI project has widely been seen mostly in economic terms, it has always had strategic meaning for the Chinese Government.

· China seeks to reform existing international economic systems through the BRI.

· There are oppositions to the BRI because the benefits to be derived by the Chinese far exceed the benefits to other participating regional countries.

· According to the World Bank statistics, the BRI financing is rapidly increasing public and corporate debt in emerging markets

Discussion Questions

[edit | edit source]· Is it fair to limit some contracts to Chinese contracts?

· How can transparency be enforced for the BRI?

· Do the overall benefits of the BRI outweigh the current human, economic and political cost?

· How else can the BRI be funded besides Chinese investments?

· Will BRI make fair trade more difficult?

For more information follow the link below

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/31878/9781464813924.pdf

References

[edit | edit source][1] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Silk Roads, Dialogue, Diversity and Development (UNESCO). Istanbul: https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/istanbul

[2] Following the conquest of Constantinople, the city was renamed to Istanbul.

[3] Peyrouse, Sebastein. The Ohio State University. Building a New Silk Road? Central Asia in the New World Order: https://origins.osu.edu/article/building-new-silk-road-central-asia-new-world-order

[4] UNESCO. The End of the Silk Road. Chapter six: https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/silkroad/files/knowledge-bank-article/the%20end%20of%20the%20silk%20route.pdf

[5] European Union. Central Asia-Transport: https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/regions/central-asia/eu-support-transport-development-central-asia_en

[6] Clinton R, Hillary. Secretary of State (2009-2013). Remarks at the New Silk Road Ministerial Meeting, September 22, 2011, New York: https://2009-2017.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2011/09/173807.htm

[7] Jinping, Xi. President of the People’s Republic of China. Transcript of the speech at the Nazarbayev University, September 7, 2013, Almaty, Kazakhstan: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/t1078088.shtml

[8] Jinping, Xi. President of the People’s Republic of China. Transcript of the speech at the Indonesian Parliament, October 2, 2013, Jakarta, Indonesia: https://reconasia-production.s3.amazonaws.com/media/filer_public/88/fe/88fe8107-15d7-4b4c-8a59-0feb13c213e1/speech_by_chinese_president_xi_jinping_to_indonesian_parliament.pdf

[9] Hui Lu, Charlene Rohr, Marco Hafner, Anna Knack, “China Belt and Road Initiative: Measuring the impact of improving transportation connectivity on trade in the region”, (RAND Europe, 2019) p. 14-15: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2625.html

[10] The World Bank Group Report, “Belt and Road Economics, Opportunities and Risks of Transport Corridors”, 2019, p 5

[11] Ibid., p. 37

[12] Ibid., p. 39

[13] John Hurley, Scott Morris, Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective”, (Center for Global Development, 2018), p. 11: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/examining-debt-implications-belt-and-road-initiative-policy-perspective.pdf

[14] An Baijie, China Daily: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-10/24/content_33644524.htm

[15] Jinping, Xi. President of the People’s Republic of China. Transcript of the speech at the Nazarbayev University, September 7, 2013, Almaty, Kazakhstan: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/t1078088.shtml

[16] Dr.Joel Wuthnow, Research Fellow, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies, U.S. National Defense University, Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later” (2018) https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Wuthnow_USCC%20Testimony_20180123.pdf

[17] CSIS, Reconnecting Asia: https://reconnectingasia.csis.org/analysis/entries/many-belts-and-many-roads/

[18] Dr.Joel Wuthnow, Research Fellow, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies, U.S. National Defense University, Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later” (2018) https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Wuthnow_USCC%20Testimony_20180123.pdf

[1] China Power, https://chinapower.csis.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative/

[2] Yiping Huang, “Understanding China’s Belt and Rad Initiative: Motivation, framework and assessment” China Economic Review, Vol 40, September 2016, pp 314-321.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1043951X16300785#fn0005

[3] Chatzky, A and McBride, J., “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative”, Council on Foreign Relations, May 21, 2019, accessed October 12th, 2019

https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative

[4] Chatzky, A and McBride, J., “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative”, Council on Foreign Relations, May 21, 2019, accessed October 12th, 2019

https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative

[5] Chatzky, A and McBride, J., “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative”, Council on Foreign Relations, May 21, 2019, accessed October 12th, 2019

[6] Yiping Huang, “Understanding China’s Belt and Rad Initiative: Motivation, framework and assessment” China Economic Review,Vol 40, September 2016, pp 314-321.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1043951X16300785#fn0005

[7] Yiping Huang, “Understanding China’s Belt and Rad Initiative: Motivation, framework and assessment” China Economic Review, Vol 40, September 2016, pp 314-321.

[1] Chatzky, A and McBride, J., “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative”, Council on Foreign Relations, May 21, 2019, accessed October 12th, 2019

https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative

NYC Fare Payment System

NYC Fare Payment System

[edit | edit source]This case reviews the Introduction of the New York City transit system’s new fare payment system. It is the collaborative work of Aleksandr Grinshpun and Lukas Camby, graduate students enrolled in George Mason University's Transportation Policy, Operations, and Logistics Program at the time of writing. The following casebook explores the key actors, policy challenges, and history associated with NYC Fare Payment System in the context of its integration into America's public transport. It was produced as an assignment for George Mason University's Introduction to Transportation Systems graduate course, taught by Dr. Jonathan Gifford.

Summary

[edit | edit source]In New York City, the earliest form of fare collection for public transit started with the nickel in exchange for a ticket. As all the transportation modes expanded and centralized, fares increased, and new technologies such as turnstiles and tokens had to be introduced to create operating efficiencies and cut costs. Some fare payment utilities were easily adopted, while others are more difficult to implement. One of the more recent fare payment technologies initiated in the 1990’s was MTA’s MetroCard.[1] These plastic cards featured a metallic strip similar to a credit card that could be swiped at a fare collection point and could also be reloaded at fare machines. This system was proposed as an alternative to the token-based system that past New York City transit companies and operators had used from the 1950’s to the 1990’s without having to ever completely overhaul the entire system.[2] A new digital system was favored. The institution of the MetroCard in 1993 was to facilitate ridership data in an attempt to improve operations.[3]

It was a huge shift for transit users at the time. Jack Lusk, a senior vice president with the MTA, told the New York Times in 1993 that “this is going to be the biggest change in the culture of the subways since World War II, when the system was unified… we think the technology is working just fine. But it may take riders some getting used to.”[4] It would take an additional 4 years until May 14th, 1997, when the entire bus and subway system accepted MetroCard. Cubic Transportation Systems designed the magnetic-stripped, blue-and-yellow card to respond to a swipe-based system. The MetroCard works in the following manner: each MetroCard is assigned an exclusive, everlasting ten-digit serial number when it is manufactured. The value on the card is stored magnetically. While each transaction on the card is recorded in the Automated Fare Collection (AFC) Database. After money is loaded onto the card and it is swiped through a turnstile, the value of the card is read, a new value is written, the passenger goes through, and the AFC is updated with that transaction.[5] Although this system was novel at the time of introduction, it quickly became notorious for its technical limitations. Only a few years after the system was introduced newer technology became available that allowed for contactless payment cards to be used. WMATA in Washington, DC introduced SmartTrip in 1999 as one of the first contactless smartcard systems used for paying transit fares in the United States.[6] Most recently, on May 31,2019, the MTA launched a pilot program of its new tap-to-pay system, known as OMNY, that is intended in due course to take the place of swiping a MetroCard. The fare technology will roll out incrementally, allowing transit officials to overcome obstacles as they work toward fully retiring the MetroCard in 2023. With OMNY, riders can bypass lines to refill their Metro cards and simply tap their contactless bank cards or mobile wallet app on their smart phones to pay the fare.[7]

Annotated List of Actors

[edit | edit source]● Public Transit Users

● MTA vice president Jack Lusk (1993)[8]

● Cubic Transportation System (MetroCard)

● Mayor David Binkens (1990-1994)[9]

● Mayor Rudi Giuliani (1994-2001)[10]

● Mayor Michael Bloomberg (2002-2013)[11]

● Mayor Bill de Blasio (2013-present)[12]

● Accepted on the following public transportation providers:

○ Rail:

■ AirTrain JFK

■ New York City Subway

■ PATH

■ Staten Island Railway

○ Bus:

■ Bee-Line

■ Hudson Rail Link

■ MTA Regional

■ Nassau Inter-County Express

○ Other:

■ Roosevelt Island Tramway

● Technology Companies

○ Apple Pay

○ Samsung Pay

○ Google Pay

● Financial Institutions

Timeline of Events

[edit | edit source]- At inception, private companies organized rapid transit routes and surface lines. Abraham Brower established New York City's first public transportation route in 1827. It was a 12-seat stagecoach called "Accommodation," that operated along Broadway from the Battery to Bleecker Street.[13]

- As of 1831, Brower had added the "Sociable" and horse drawn "Omnibus."[14]

- In 1832, John Mason organized the New York and Harlem Railroad, that used a street railway powered by horse-drawn cars with metal wheels running on metal track.[15]

- As early as 1855, 593 omnibuses traveled on 27 Manhattan routes and horse-drawn cars ran on street railways on Third, Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Avenues.[16]

- Before any underground excavation commenced for the "official" underground subway in 1900, under the management of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Corporation (BRT), the City of Brooklyn was serviced by a series of elevated railway lines referred to as "Els".[17]

- From 1870 to 1873, Alfred E. Beach created a 312-foot tunnel under lower Broadway and ran a subway car operated by "pneumatic pressure."[18]

- In 1872, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT)[19] began operating the first El in Manhattan along Ninth Avenue.[20] The elevated lines accommodated efficient rapid transit service, with frequent trains, a cheap fare, and swifter travel time than street traffic.[21] However, these wooden cable cars powered by steam, were prone to mechanical malfunctions such as; snapped cables, engine problems, and track fires.[22]

- Nearing the end of the 19th century, the adoption of electricity on trolley cars, led to the replacement of horses for propulsion. [23]

- New York City's first ‘official’ subway system opened its doors for business in Manhattan on October 27, 1904.[24]

- Until May 10, 1920, to pay for their fare Subway customers purchased tickets which cost $0.05.[25]

- IRT service expanded to the Bronx in 1905, to Brooklyn in 1908, and to Queens in 1915. Also in 1915, the BRT began subway service between Brooklyn and Manhattan. Shortly after, the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) absorbed the BRT.[26]

- Trolley bus lines, also called trackless trolley coaches, used overhead power lines to serve Staten Island in the 1920s.[27]

- Beginning in 1930, for three decades, Brooklyn's surface transit were also reliant on trolley bus lines.[28] However, by 1956 and 1960, motor buses had become the dominant form of New York City public transit, replacing trolley cars and trolley buses.[29]

- The first city-run subway service began service in 1932, when the NYC's Board of Transportation completed construction of the Eighth Avenue line and created the Independent Rapid Transit Railroad (IND).[30]

- Post the purchase of the BMT and IRT in 1940, NYC's Board of Transportation became the sole owner and operator of all the city’s subway and elevated lines.[31]

- Towards the late 1940’s, the city also acquired three other bus companies that operated in Queens and Staten Island.[32]

- From 1920 through 1948, turnstiles were introduced for fare payment collection as a cost-cutting initiative in response to post-World War I inflation.[33]

- In 1948, turnstiles started accepting dimes once the fares were increased by 5 cents.[34]

- On June 15, 1953, the New York State Legislature formed the New York City Transit Authority (now MTA New York City Transit) as a separate public entity to manage and operate all city-owned bus, trolley, and subway routes.[35]

- Since turnstiles couldn't handle two different coins, tokens replaced coins in 1953, when the fare rose to 15 cents.[36]

- In 1970, NYCTA released a larger version of the classic Y token in 1970 to accompany a fare increase to 30 cents.[37]

- In 1979, for the anniversary of the Subway, the Diamond Jubilee token was unveiled. The commemorative token had a fare value of 50 cents.[38]

- In 1980, the city introduced the Solid Brass NYC token, which featured an updated design.[39]

- 1986 brought a new token called “bull’s eye,” and “fare rose to $1 a trip.”[40]

- In 1995, the MTA introduced the symbolic “Five Boroughs” token, the last token before the MetroCard, which was phased out in 2003. This token was valued at $1.50.[41]

- In 1993, the MetroCard was introduced.[42]

- When WMATA launched SmartTrip in 1999, it was the nation’s first contactless smart card for transit.[43]

- On May 31,2019, the MTA launched a pilot program of its new tap-to-pay system, known as OMNY, that is intended to replace swiping a MetroCard. The fare technology is expected to be released in phases, allowing transit officials to identify complications and find solutions prior to fully retiring the MetroCard in 2023.[44]

History of NYC Public Transit Fares

[edit | edit source]● $0.05 (1904– July 1, 1948)

● $0.10 (July 1, 1948 – July 1, 1953)

○ Bus fare: $0.07 from 1948 until 1950 and $0.10 from 1950 till 1953

● $0.15 (July 2, 1953 – July 5, 1966 )

○ Bus fare: $0.13 from 1954 till 1955 and $0.15 from 1956 till 1966; 5th Avenue Bus line fare raised to 15 cents on January 1, 1954

● $0.20 (July 5, 1966 – January 3, 1970 )

● $0.30 (January 4, 1970 – December 31, 1971 )

● $0.35 (January 1, 1972 – August 31, 1975 (MSBA/Long Island Bus from 1973)

In December 1973, the MTA started trialing a program in which passengers could pay a single one-way fare to take round trips on the subway, buses, and railroads on Sundays. Since this resulted in higher ridership, the MTA extended it through the beginning of 1975.

● $0.50 (September 2, 1975 – June 27, 1980 )

● $0.60 (June 28, 1980 – July 2, 1981 )

● $0.75 (July 3, 1981 – January 1, 1984 )

● $0.90 (January 2, 1984 – December 31, 1985 )

● $1.00 (January 1, 1986 – December 31, 1989 )

● $1.15 (January 1, 1990 – December 31, 1991 )

● $1.25 (January 1, 1992 – November 11, 1995 )

● $1.50 (November 12, 1995 – May 3, 2003 )

● $2.00 (May 4, 2003 – June 27, 2009 )

● $2.25 (June 28, 2009 – December 29, 2010 )

● $2.25 base fare (December 30, 2010 – March 2, 2013 )

● $2.50 SingleRide MetroCard ticket fare

● $2.50 base fare (March 3, 2013 – March 21, 2015 )

● $2.75 SingleRide MetroCard ticket fare

● $2.75 base fare (March 22, 2015 – present)

● $3.00 SingleRide MetroCard ticket fare

Maps of Location

[edit | edit source]Policy Issues

[edit | edit source]● Too old or too new? Since the system used technology that has only been tried in a few other places, the MTA is being extremely ambitious with the OMNY project. They are also putting a huge amount of confidence that the technology will work seamlessly. Contactless smartcard systems are now the standard method of paying for transit fares in many parts of the world and many people have long been perplexed about why the New York City transit system has used a system that feels very obsolete by comparison as it was developed using early 1990’s technology. The root of the problem is that New York switched from tokens to electronic reloadable fare cards a little early, before the technology developed further just 5 years later to allow for a contactless system adopted by WMATA. Although WMATA’s SmartTrip system is not without its problems, it is still a very reliable system that has completely replaced the disposable farecards that the Washington Metro used beforehand. While the system was cutting edge at the time of its installation, the technology of fare payments advanced very quickly and obsolescence by the late 2000’s was inevitable.

● Misuse of Technology As with all new technologies, the public is concerned that their personal identifying information (PII) may be put at risk in a contactless fare system. Policymakers will have to ensure that appropriate data security measures are in place and evolve as new cyber threats emerge. Furthermore, an aversion to government-operated technology systems among the general public may give rise to skepticism over this method of payment. Although this phenomenon is already taking place with the MetroCard, the fact that contactless fare payment may cross over ridership information with PII may be worrisome to certain users.

Additionally, fare evasion/insufficient funds will continue to be an issue with contactless fare technology. Systems will need to ensure collection of fares prior to boarding or the beginning of a trip to avoid freeloading off of the system. Non-collection of fares may put a burden on MTA’s bottom line.

● Advertising on Metro Cards Metro cards have long been used for advertising. Pilot programs that started in the early 2000’s undertaken to see how effective advertisements were for the Metro cards. The program was expanded in 2012 when the entire card was put on offer for advertisement space, this created a frenzy of companies placing logos and messages on New York City farecards. While advertising on transit is far from a new idea, the concept of placing advertisements on transit fare cards has rarely been done on a large scale before. The benefits of this program include added revenue from a larger cohort of advertisers and much greater flexibility of ad selection and variety than compared to using physical wraps on trains. This policy however has been criticized for creating some confusion amongst transit riders about the need for consistency in the appearance of the cards. Some have also questioned why some cards have ads while others don’t and that the fare remains the same regardless it the card has an ad or not. While the new system will feature new cards with the OMNY logo, it is yet to be seen on whether the new cards will feature ads.

● Lack of connectivity with other transit systems in the region such as, NJ transit. While the OMNY program is going to be compatible with all services operated by MTA including the subway, local buses, express buses, LIRR, and Metro-North. Compatibility with these extra services will be added in stages as OMNY begins its proving ground operations with the subway. But one notable transit agency in the region that will not be participating in ONMY is New Jersey Transit which operates NJ Transit Rail and many local and express buses that serve urban and suburban communities in Northern New Jersey. They will be using a different system developed by Conduent of Florham Park, NJ. This lack of connectivity will be notable given how most large urban areas have favored developing a single smartcard payment system that works amongst all major transit providers in an area such as WMATA for the Washington, D.C. area. While the need for connections and compatibility has been addressed within MTA, the concerns over lack of coverage with the services outside the state of New York have been a cause of concern. Advocates want the system to be as integrated with all services in the region as it can be, and as things are currently developing, a commuter from New Jersey may have to maintain 2 cards in their wallet so that both NJ Transit services and MTA services can be used conveniently. The issue has existed for a while as NJ Transit has long had their own train and bus tickets.

● Half- priced fares and Access-A-Ride New York City has instituted a system of reduced fares in recent years for enabling low-income people to use the subways in a more affordable fashion. The programs issues special Metro cards for those who qualify by submitting a request to the MTA. The introduction of the new OMNY system has been met with concerns from some advocates that the new system is inherently disadvantageous to low income subway user in that it will make it more difficult to have access to these kinds of benefits when the new system becomes dominant. MTA has not yet specified how it plans to keep these benefits going once OMNY is fully installed and operational.

● The issue of cash users. Although the new system will dispense reloadable smartcards from fare machines that accept cash, OMNY has been criticized for being another example of how technological change is making cash users feel like they are a burden. OMNY will feature credit card payment options both online and at physical fare machines that will be universally accepted. MTA has not provided details on how the new cards will be distributed to those who wish to continue to use cash to pay for their fares. WMATA in the D.C. area faced early criticism for SmartTrip cards being only available in a few select stations and that the cards cost $10 a piece. The MTA of New York will almost certainly suffer similar criticisms once these new machines that dispense OMNY cards are put into service.

Narrative of the Case

[edit | edit source]New York City’s public transportation fare payment has evolved with the demands of an expanding system. However, one could argue that fare payment technology has not kept pace with the ridership volume created by that expansion. The earliest form of fare payment was five cents in exchange for a ticket to board. In the 1920’s turnstiles were introduced to lower costs associated with operating public transit. Since turnstiles were unable to accept multiple coins for payment as fares increased, tokens became the currency to board public transit. However, tokens are unable to provide ridership data that the MTA urgently craved. Collecting data would allow for knowing “the exact location and time that every rider entered the station or boarded a bus.” In theory, this data would allow for better planned routes serving the ridership population when needed at a reduced operating cost. As such, the magnetic strip MetroCard was introduced in the early 1990’s. These Metro cards are still in use today. In May 2019, MTA launched its new tap-to-pay system, known as OMNY, that is intended to replace the MetroCard.

Unfortunately, some technologies are more adaptable than others. For example, the exchange of coins for tickets is straightforward. The later iteration of exchanging coins for tokens is also a concept that is easy to implement. Turnstiles were also easily accepted by the public. On the other hand, transitioning from tokens to the MetroCard provided challenges for both users and the MTA. The AFC made frequent errors in tracking values held on Metro cards. Turnstiles often were not able to read the cards and users found ‘hacks’ to game the system and gain free ridership.

The introduction of the new payment system for the New York City subway has been touted as a crucial step forward for the public transportation system of America’s most populous city. As other cities around the world have been aggressively adopting new technologies into their operations, the MTA has taken key notice. With the introduction of other fare payment systems that use contactless cards in the united states and some systems introducing smartphone based payment systems, the New York City subway system’s fare payment technology has become notably outdated by comparison in recent years. The system is in desperate need of an update as eventually the Metro card system will become incompatible with other technologies and the existing system would need the be maintained through contractors that no longer make the required components and software making the system much more expensive to operate. The fare payment system update is also a great way for the MTA to tout the continued advancement and upgrading of the system, as the subway has long struggled with a perception of widespread infrastructure woes due to the age of the system and has tried to find innovative ways of solving these pressing problems and restoring rider satisfaction for a city as globally important as New York.

In order to restore ridership and give the public greater satisfaction when using public transit, MTA is converting to a OMNY, a contactless fare payment system, wherein riders will be able to bypass lines to refill their Metro cards and simply tap their contactless bank cards or mobile wallet app on their smart phones to pay the fare. Metro cards, which are 25 years old, “run on OS2,” an obsolete operating system deemed “‘no longer supportable’” by MTA leadership. User experience is also expected to improve, with leaders aiming to facilitate “‘end-to-end connectivity’ across” multiple modes of MTA-offered transit. This contactless feature is supposed to support saving riders their most valued commodity - time.

From a technical standpoint, an update is a must. But an update is not without consequences for the riders who are used to the current system. The new system has such a heavy reliance on the latest technology of fare collection that some who are used to the relative simplicity and familiarity of Metro cards may be somewhat apprehensive about adopting the new system. While the benefits from the installation of the new system will only become apparent as the new fare and turnstile machines are implemented. Lessons Learned

As with all new technologies, there is an evolution throughout the birth, growth, and maturity stages. One can say that the implementation of the MetroCard was like implementing developed technology in an age that favored more innovative data tracking and management systems. It is also quite surprising that the most-used transit system in the United States has taken over 20 years, or well into the maturity stage, to adopt contactless fare payment technology. While newer metropolitan transit systems, such as WMATA in Washington, DC, were able to leverage such technology from their inception, NYC’s MTA was forced to retrofit older existing technology and infrastructure. The introduction of the OMNY fare payment system for New York City is one of the most notable developments in the story of American public transportation. The technological developments that have led New York City to this point in fare collection have been extensive and pose a unique challenge for a city where more than 1 billion rides are made on public transit within the city limits annually. With the scale of this new payment system’s implementation comes a multitude of challenges that have to be addressed and solved both before the system is designed and before it is fully tested, proven, and completely operational. Discussions about the adoption of new technology on a systemwide scale have been made within the wider New York City community, as have how these decisions will affect the way New Yorkers pay their transit fares decades to come. But some of the most important lessons have come from how the technology has already progressed and discussions about ensuring fairness in an urban space as complicated and multifaceted as New York. How an agency balances the pros and cons of a technical update like this is the key issue that can be observed from this development and what it does for the people who actually use the transit system. Does it increase efficiency over the long run? Is it a technical burden for all those involved? Is a city like New York truly ready for a system like this? Are we able to foresee the consequences and potential shortcomings to this technology? Is OMNY being truly embraced by city leadership the way MetroCard was? These questions and the lessons we can gain from the New York City experience will set a precedent for other large cities as they move from old fare collections systems to newer ones.

Discussion Questions

[edit | edit source]● How does fare payment matter for transit users? ● Does technological change make fare payment harder or easier? ● How can transit agencies learn from the experience of MetroCard to make informed decisions on when to make updates to fare payments? ● Do you think that MetroCard was a victim of its early success and age? ● How does fare payment technology evolve further beyond contactless smartcard and smartphone based payment technologies? ● Is New York City the ideal proving ground for a system like OMNY?

Assigned Readings

[edit | edit source]Spivack, Caroline. “A Guide to OMNY, the MTA’s New MetroCard-Replacing Fare System.” Curbed NY. Curbed NY, May 22, 2019. https://ny.curbed.com/2019/5/22/18617849/nyc-subway-mta-omny-contactless-payment-system. “NYC Subway History: The Story of Fares, Tokens & Cards,” Living In | CitiHabitats.com, June 6, 2018, https://livingin.citihabitats.com/nyc-subway-history-the-story-of-fares-tokens-cards/.

“Mta.Info | Facts and Figures,” Mta.info, n.d., http://web.mta.info/nyct/facts/ffhist.htm.

References

[edit | edit source]“15C FARE STARTS; LINES FORM TO BUY TOKENS IN SUBWAYS; Half of Turnstiles Converted by Deadline -- Mechanics Work Through the Night FEW HITCHES REPORTED Quota of Disks Is Raised to 5 -- 2 Restaurants Offer to Take Them for Food FARE RISES TO 15C ON ALL CITY LINES.” The New York Times, July 25, 1953. https://www.nytimes.com/1953/07/25/archives/15c-fare-starts-lines-form-to-buy-tokens-in-subways-half-of.html.

Adam Clark Estes. “The Cursed History of NYC MetroCards.” Gizmodo. Gizmodo, October 23, 2017. https://gizmodo.com/the-cursed-history-of-nyc-metrocards-1819774428.

“Approved Fares for NYC Transit, MTA Bus, Long Island Bus and the Staten Island Railway Effective December 30, 2010.” Archive.org, 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20101122052827/http://mta.info/mta/pdf/approved_fares.pdf

Boorstin, Robert O. “ALL OVER CITY, TRANSIT FARE TRANSITIONS MADE Of.” The New York Times, January 1, 1986. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/01/01/nyregion/all-over-city-transit-fare-transitions-made-of.html.

Cavan, Sieczkowski. “MTA Approves MetroCard, Single-Ride Fare Hike For 2015.” HuffPost Canada. HuffPost Canada, January 22, 2015. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/mta-metrocard-fare-hike_n_6525462.

“Costlier Token.” The New York Times, September 2, 1975. https://www.nytimes.com/1975/09/02/archives/costlier-token.html.

“Display Document.” Thejoekorner.com, 2011. http://www.thejoekorner.com/scripted-ticket-display.shtm?http://www.thejoekorner.com/brochures/fare-changes-2003.gif.

Donohue, Pete. “MTA Subway Fare Hike Takes Effect on Sunday, Price Rises to $2.25 per Ride.” Nydailynews.com, 2018. https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/mta-subway-fare-hike-takes-effect-sunday-price-rises-2-25-ride-article-1.373236.

Evelly, Jeanmarie. “City’s Half-Priced MetroCard Program Continues to Expand, But Frustrations Persist.” City Limits, October 2, 2019. https://citylimits.org/2019/10/02/citys-half-priced-metrocard-program-continues-to-expand-but-frustrations-persist/.

“Expect Long Lines for Tokens.” The New York Times, November 11, 1995. https://www.nytimes.com/1995/11/11/nyregion/expect-long-lines-for-tokens.html.

Fitzsimmons, Emma G. “M.T.A. Is Raising Fares and Tolls; One Subway or Bus Ride Will Cost $2.75.” The New York Times, January 22, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/23/nyregion/mta-raises-fares-subways-and-buses.html.

Frost, Mary. “What’s Going on with OMNY, Public Transit’s New Fare-Payment System?” Brooklyn Eagle, August 23, 2019. https://brooklyneagle.com/articles/2019/08/23/omny-public-transits-new-fare-payment-system/.

“Half‐Fare Plan Extended To’75.” The New York Times, May 24, 1974. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/05/24/archives/halffare-plan-extended-to75-5-holidays-added.html.

https://viewing.nyc/authors/coneybeare, and Matt Coneybeare. “Check Out This Great Schematic-Style Redesign of the New York City Subway Map.” Viewing NYC. Viewing NYC, June 7, 2019. https://viewing.nyc/check-out-this-great-schematic-style-redesign-of-the-new-york-city-subway-map/.

Illson, Murray. “M.T.A. Ready for 2‐for‐1 Fare Test Tomorrow.” The New York Times, December 15, 1973. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/12/15/archives/mta-ready-for-2for1-fare-test-tomorrow.html.

“Mayors of the City of New York.” Nyc.gov. Accessed November 17, 2019. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/dcas/about/green-book-mayors-of-the-city-of-new-york.page.

Meislin, Richard J. “FARE RISES TO 75¦; TRANSIT TAX PLAN DRAWN IN ALBANY.” The New York Times, July 3, 1981. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/07/03/nyregion/fare-rises-to-75-transit-tax-plan-drawn-in-albany.html.

“MTA - News.” Archive.org, 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20030614085656/http://www.mta.info/mta/news/public/fares/nyct.htm.

“M.T.A. Is Raising Fares and Tolls; One Subway or Bus Ride Will Cost $2.75.” The New York Times, January 22, 2015.

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/23/nyregion/mta-raises-fares-subways-and-buses.html.

“Mta.Info | Facts and Figures.” Mta.info, n.d. http://web.mta.info/nyct/facts/ffhist.htm.

“Mta.Info | New Fares - Effective March 3, 2013.” Archive.org, 2013.

https://web.archive.org/web/20130224131911/http://www.mta.info/nyct/fare/NewFares.htm.

Nonko, Emily. “The History of the New York City MetroCard | 6sqft.” 6sqft, November 8, 2017. https://www.6sqft.com/the-history-of-the-new-york-city-metrocard/.

“NYC Subway History: The Story of Fares, Tokens & Cards.” Living In | CitiHabitats.com, June 6, 2018. https://livingin.citihabitats.com/nyc-subway-history-the-story-of-fares-tokens-cards/.

“Old and New Commuter Fares in New York Area.” The New York Times, June 30, 1980. https://www.nytimes.com/1980/06/30/archives/old-and-new-commuter-fares-in-new-york-area.html.

Ormsbee, Brian. “A Historical Look at the New York City Subway - 100 Years Underground.” Cooperator.com, December 2004. https://cooperator.com/article/100-years-underground/full.

Prial, Frank J. “TOKEN UNCHANGED.” The New York Times, January 5, 1972. https://www.nytimes.com/1972/01/05/archives/token-unchanged-mta-also-votes-rise-in-tolls-for-bridges-and.html.

Raschke, Kurt. “A Brief History of Metrorail Fare Collection.” Ggwash.org, July 8, 2011. https://ggwash.org/view/9979/a-brief-history-of-metrorail-fare-collection.

“Report for the Three and One-Half Years Ending June 30, 1949.” HathiTrust, 2016. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015023094926&view=1up&seq=6.

Robinson, Douglas. “New Tokens Go on Sale in Subways.” The New York Times, January 3, 1970. https://www.nytimes.com/1970/01/03/archives/new-tokens-go-on-sale-in-subways-30cent-tokens-are-put-on-sale-at.html.

“Same Subway Token Despite Fare Increase.” The New York Times, January 2, 1984. https://www.nytimes.com/1984/01/02/nyregion/same-subway-token-despite-fare- increase.html.

Schmitt, Eric. “Transit Lines Brace for Test Of $1.15 Fare.” The New York Times, January 2, 1990. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/01/02/nyregion/transit-lines-brace-for-test-of-1.15-fare.html.

Spivack, Caroline. “A Guide to OMNY, the MTA’s New MetroCard-Replacing Fare System.” Curbed NY. Curbed NY, May 22, 2019. https://ny.curbed.com/2019/5/22/18617849/nyc-subway-mta-omny-contactless-payment-system.

Steinberg, Jacques. “That Extra Dime Is a Little to Some, a Lot to Others.” The New York Times, January 1, 1992. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/01/01/nyregion/that-extra-dime-is-a-little-to-some-a-lot-to-others.html.

“TAKING OVER 10 NASSAU BUS LINES.” The New York Times, December 28, 1972. https://www.nytimes.com/1972/12/28/archives/mta-taking-over-10-nassau-bus-lines.html.

“Variations in Fare.” Nytimes.com, 2019. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1966/07/05/82469245.html.

“Www.Nycsubway.Org: Subway FAQ: Which Lines Were Former IRT, IND, BMT.” Nycsubway.org, 2012.

https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Subway_FAQ:_Which_Lines_Were_Former_IRT,_IND,_BMT.

Yohana Desta. “1904 to Today: See How New York City Subway Fare Has Climbed over 111 Years.” Mashable, March 22, 2015. https://mashable.com/2015/03/22/new-york-city-subway-fare/.

Supersonic Flight Integration

Supersonic Flight Integration

[edit | edit source]This case reviews the Challenge of Integrating Supersonic Flight into American Airspace. It is the collaborative work of Alexander Merker and Farida Ibrahim, graduate students enrolled in George Mason University's Transportation Policy, Operations, and Logistics Program at the time of writing. The following casebook explores the key actors, policy challenges, and history associated with supersonic commercial flight in the context of its potential reintegration into America's national airspace. It was produced as an assignment for George Mason University's Introduction to Transportation Systems graduate course, taught by Dr. Jonathan Gifford.

Summary

[edit | edit source]In the early 2010s, interest in commercial supersonic air transport (SST) was renewed as advances in technology and an increasing demand for private and business air travel created a market niche for faster and longer-range aircraft. Supersonic air travel, that which exceeds the speed of sound, offers considerable speed advantages over subsonic flight. The Concorde, a first-generation supersonic airliner, completed air travel to London in only 2 hours, a third of the time its subsonic competitors took to complete the journey. The speed advantage of supersonic aircraft is a strong selling point in the private and business aviation market, where time-savings are a principal reason for ownership.[45]

However, allowing supersonic aircraft to fly at their intended speeds in American airspace poses the same challenges it did over half a century ago when the first wave of supersonic airliners was in active development. The most significant regulatory barrier to supersonic aircraft is a Federal Aviation Administration ban on overland supersonic flight by civil aircraft in American airspace, which was enacted during the first wave of supersonic airliners in 1973.[46] This ban and the public perceptions behind it remain a barrier to integration of such air travel into American airspace, with additional concerns regarding the environmental impact of the pollution generated by these aircraft contributing to public perception issues.[47]

Annotated List of Actors

[edit | edit source]Aerospace Manufacturers

[edit | edit source]- Boom Technology

- Aerion Supersonic

- Spike Aerospace

- The Boeing Company

- Lockheed Martin

Federal Aviation Administration

[edit | edit source]- Responsible for the regulation and oversight of airspace in the United States, the FAA establishes rules relating to supersonic flight in American airspace

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

[edit | edit source]- NASA provides research into the effects of supersonic flight, in addition to developing sonic boom dampening technologies

Environmental Groups

[edit | edit source]- The Anti-Concorde Project

- International Council on Clean Transport

International Civil Aviation Organization

[edit | edit source]- United Nations body responsible for maintaining international standards for air travel

Timeline of Events

[edit | edit source]1962: The British and French merge their development efforts and the Concorde Project begins

1963: Development of the Soviet Tu-144 begins

1967: The American SST Program selects the Boeing 2707 as its production design

1971: The American SST Program is cancelled

1973: The Federal Aviation Administration bans all civil aircraft from exceeding Mach 1 over land in American airspace

1975: The Tu-144 enters regularly scheduled service

1976: Concord begins regularly scheduled service

1983: The Tu-144 is retired from service

2003: British Airways and Air France retire the Concorde

2006: NASA begins its Quiet Spike sonic boom mitigation test program

2018: NASA begins construction of the QueSST Supersonic Demonstrator

2018: The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) implements the Reauthorization act of 2018 which grants the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) the power and authority to establish new federal and international policies to regulate and certify safe and efficient civil supersonic aircraft operations.

2020: Expected first flight of the Boom Technologies XB-1 Supersonic Demonstrator

2021: Expected first flight of NASA’s X-59 QueSST Supersonic Demonstrator

2023: Intended date of first flight for the Aerion AS-2 Supersonic Business Jet

Maps of Locations

[edit | edit source]

A Map of Concorde's Flight Path

Policy Issues

[edit | edit source]Noise Concerns

[edit | edit source]The primary regulatory concern involving supersonic aircraft is their trademark sonic boom. The sonic boom can be defined as “a shock wave of pressure created by compression of sound waves as the air is displaced by the air-frame traveling at or above Mach 1”.[48] This shock wave of pressure results in a large ‘boom’ that are often compared to the clap of thunder. It is for this reason, that public pressure on the federal government was high in regards to the sonic booms created by aircraft travelling faster than Mach 1. The public skepticism surrounding supersonic flight was fueled by the belief that supersonic aircraft would be detrimental to public health and damaging to property. As a result, the federal government amended the existing Federal Aviation Act of 1958 to include a section that gave the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) the capacity to extend already set noise standards of civil subsonic aircraft to supersonic civil airliners. As a result, the Control and Abatement of Aircraft Noise and Sonic Boom Act of 1968 was implemented.[49] However, in 1973 the Federal Aviation Authority issued a ban on all civil air travel exceeding the sound barrier (Mach 1) over land in American airspace. To date, this ban remains the largest policy barrier for commercial supersonic aircraft in the United States. This is largely because it limits the capacity of supersonic airliners to service a large surface area and to expand its routes.

Studies into the subject of the sonic boom and the impact on health and property have yielded a an uncertain measurement of the impact of sonic boom pressure shock waves on the general population. As far back as the 1950s, studies have found that the impact of sonic booms is heavily dependent on factors such as aircraft altitude, atmospheric conditions and body shape.[50] The most physical aspect of sonic booms, its characteristic pressure shock wave, was found by NASA to have been at a measurement 1.94 psf for the Concorde under normal flight conditions. This is at the cusp of the 2-5psf, what NASA categorizes as “Rare minor damage”, and above the 1.0 psf where public reaction is seen. However, the perceived impact of sonic boom in the form of shattered windows and other structural damage, has not been found to occur below 11 psf.[50]

However, the opposing opinions on the effects of the supersonic aircraft have led to numerous debates between policy makers and supersonic flight proponents. This has resulted in continued dialogue between supersonic aircraft manufacturers and government agencies, such as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Since the ban in 1973, stakeholders within the aerospace industry and NASA have worked to develop a better understanding of sonic boom and solutions for mitigation. Examples of this include NASA's Quiet Spike test bed.[51]

With the resurgence of interest in supersonic transport technology, a renewed effort against the technology has emerged as well. In a series of announcements, the FAA pledged to acknowledge the technological differences between supersonic and subsonic aircraft and take it into consideration when assessing noise requirements.[52] This was a significant achievement for the technology, showing both maturity in sonic boom mitigation developments, as well as changing perspectives on its impacts.

So far, dialogue between supersonic aviation and policy makers have remained open and productive as agencies such as the FAA have expressed willingness to modify current policies if supersonic airliners are able to achieve a sound level comparable to that of their subsonic counterparts.[53] This signifies a shift in trends among policy makers as the FAA has shown willingness to revisit the issue and possibly lift the ban if provided with adequate research to support the stance that supersonic airliners will not be damaging to physical property, the environment, or the human body.

In 2019, the International Council on Clean Transport, an environmental advocacy organization focusing on transportation, produced a report outlining the potential environmental impacts of this technology under current fleet projections made my potential manufacturers.[54] This report concluded that regions under the most traveled supersonic flight paths might experience sonic booms up to 200 times a day. The United States, United Kingdom and United Arab Emirates were expected to be the most traversed of all counties in this projected scenario for 2035.

Research into this topic continues at the same time NASA and the FAA work towards re-defining the standards for overland supersonic flight and an end to the ban on such air travel.[55] One of the goals of NASA’s X-59 supersonic technology demonstrator is to build a supersonic aircraft that produces a reduced overland sonic boom. As a result, the X-59 has been marketed as a quieter supersonic aircraft with a mission to elicit public feedback on the impact of the modified produced for the purposes of reopening U.S. airspace to supersonic flight.[56]

Environmental Concerns

[edit | edit source]Rising concerns over climate change have resulted in an increasingly environmentally conscious society. As a result, environmental groups stand in opposition to the reintegration of supersonic transports into the national airspace. In addition to concerns over the impact of sonic booms, another concern for environmental groups are the emissions created by these aircraft which could potentially deplete the stratospheric ozone layer.[57]

A 1966 scientific study by the American National Academy of Sciences confirmed that exhaust emissions released from supersonic jetliners are harmful to the stratosphere and could contribute to climate change. The research showed that “a five-fold increase in the amount of water vapor would lead to a two degree Celsius increase in surface temperatures”.[58] A 2019 study on the carbon emissions impact of supersonic commercial aviation found that it would contribute to a substantial increase in such emissions.[59]

In addition, a 1972 report by future Nobel Laureate Paul Crutzen, also found that nitrous oxide emissions from supersonic transport engines might have a significant impact on ozone depletion.[60] This study was used as the basis for environmental agreements made by anti-SST organizations such as the Anti-Concord Project.[61] Crutzen's work on ozone depletion would eventually lead to research which was crucial to the understanding of the human influence on climate change, for which he won a Nobel Prize.[62]

More recently, a 2019 ICCT report on the environmental impacts of supersonic commercial aviation found that it would contribute to a substantial increase in carbon emissions.[63] The study determined that a hypothetical global fleet of 2000 supersonic aircraft (as proposed by proponents of the technology) would emit a carbon footprint equivalent to 59% of the combined fleets of all American air carriers in 2017.

The issue of carbon footprint is a growing area of concern for the technology, as governments and airlines take increasingly aggressive measures to reduce carbon emissions in air travel. In 216, the United Nations body responsible for international aviation standards, The International Civil Aviation Organization, set in place a carbon emissions reduction program for international air travel.[64] These strict standards are likely to conflict with the reintegration of commercial supersonic aircraft, though developers of the technology like Boom Technologies have claimed that their use of bio fuels over kerosene will have an mitigating effect on their carbon emissions, with its XB-1 test aircraft being "..history’s first zero net carbon footprint on a supersonic flight,".[65]

Narrative of the Case

[edit | edit source]The First Wave of SST Development

[edit | edit source]In the early 1960s, airlines and aerospace manufacturers believed that the future of air travel would be through supersonic aircraft. Seeking to gain an advantage in an advantage for both their manufacturers and airlines, the United Kingdom, France, Soviet Union and the United States invested in programs to develop and produce supersonic airliners.[66] The United Kingdom and France quickly merged their efforts, developing a partnership to build the Anglo-French Concorde.[67] The United States, with a large manufacturing base to draw upon, selected two competing designs for further government investment in what was known simply as the SST Program.[68] The Soviets utilized their Tupolev design bureau to develop their supersonic transport, the Tu-144.[69]

In 1964 the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) authorized a series of tests flights to be carried out in Oklahoma City. The purpose of these tests were to measure the effects of supersonic booms on the environment and also what physical effects it would have on civilians on the ground.[70] These experiments were controversial as it was during this phase, that residents concentrated within these areas began to raise concerns about the loudness of supersonic engines and the damage it was doing to their property.[71] Many people submitted claims to the government requesting compensation for broken windows, cracked tiles and other damage to physical property. In addition, there were also numerous complaints regarding the noise levels and the associated thunder claps. These experiences contributed heavily to the formation of public opinion as the experiences of individuals within this city continued to spread across the United States influencing the ideas and opinions about supersonic flight. By 1966, The Anti-Concorde project was formed to counterbalance the claims of the aerospace industry about the technical and economic viability of the Concorde program. This created the opportunity for people who shared similar views, to rally together collectively bargain against the Concorde. It became one of the most predominant groups in opposition to supersonic air travel, as it assembled a group of experts to publish information regarding the extensive fuel consumption, and sonic booms that would result from supersonic airliners.[61] The project would also publicize the facts about the economics of Concorde; that the plane could not be operated at a profit, and that the research and development costs, funded entirely with taxpayer's money, would never be recovered.[72] The anti-Concorde project used this information to lobby against the aerospace industry to end all supersonic transport projects on economic and environmental grounds.

Facing both intense scrutiny for its environmental impacts and a transition by American air carriers to high-capacity subsonic aircraft, the United States cancelled its supersonic airliner program (SST) in 1971 before a prototype could fly.[73] Boeing, the winner of the design competition for the SST program, was forced to lay off more than 60,000 employees as a result of the program’s cancellation.[74] Shortly after the end of the SST Program, the Federal Aviation Administration would ban all overland supersonic flight by civil (non-federal) aircraft in 1973.[75] The ban remains in place to this day.[76]

The Anglo-French Concorde and Soviet Tu-144 projects continued despite challenges in public perception and airline economics. The Concorde and Tu-144 entered full commercial service in the mid-1970s, achieving the project goals. However, they still faced challenges. The Tu-144, which suffered a fatal crash on the world stage at the 1971 Paris Airshow, was found to be ill-suited for passenger air travel due to high internal noise levels and serious reliability issues.[77] As a result, the Soviet Union retired the Tu-144 from commercial airline service less than a decade later in 1983.

After the retirement of the Tu-144, the Anglo-French Concorde maintained its status as the only active commercial supersonic aircraft despite challenges involving public perception and the economic viability of the project. The Concorde fared far better than the Tu-144, remaining in service until 2003. Serving the national flagship carriers of the United Kingdom (British Airways) and France (Air France), fourteen Concorde's provided transatlantic supersonic air travel between their national capitols and New York City.[78] The Concorde was not the commercial success it was intended to be though. The economics of operating the fuel inefficient aircraft, which sat only 100 passengers, were compounded by bans on overland supersonic travel that eliminated all but one destination outside of Europe.[79] In comparison, the Concorde’s subsonic competitor Boeing 747 sat 660 passengers and consumed half the amount of aviation fuel during an equivalent flight between New York and London.[80] By the 2000s, increasing costs of fuel and maintenance led to the retirement of the aircraft from both fleets, bringing an end to supersonic commercial air travel.

Continuing Investment in SST Technology

[edit | edit source]

Despite the cancellation of the American SST Program, supersonic aircraft testing and research was not abandoned entirely in the United States. NASA continued to study potential evolutions of the design and made notable contributions to the cause by offering potential solutions to the design challenges that led to the cancellation of the SST.[81] NASA, through its research, continued to influence supersonic transport development and remained a fundamental contributor to the study of supersonic flight. This included a partnership with its Russian counterparts in 1996 for continued supersonic transport development, retrofitting a Tu-144 for test flights that were conducted through 1999.[82] More recently, NASA studied supersonic boom mitigation through Quiet Spike Program, which mounted a modified nosecone to an F-15B aircraft to test experimental structural solutions to the issue.[51]

The Second Wave of SST Development

[edit | edit source]Currently, in response to renewed business interest in such aircraft, NASA is in the final development stages of the X-59 Quiet Supersonic Transport experiment aircraft that will demonstrate new technologies and design methods for civilian supersonic aircraft.[83] The overall goal of this program is to develop sonic boom dampening technologies that will allow for a return to overland supersonic travel.

Outside of government initiatives into this technology, private industry has taken a strong interest in the prospects of supersonic air travel for private and business aviation. In these markets, where time savings are the commodity being purchased, the benefits of supersonic air travel are clear over current aircraft. The current fastest business aircraft, the Cessna Citation X+, has a top speed of Mach 0.935, just below the sound barrier.[84] Aerospace startups Boom Technologies and Aerion Supersonic believe that their in-development supersonic business jets will fill this market niche.[85]

The first tests of new supersonic transport demonstrator aircraft are expected to take place in the early 2020s. The NASA developed and Lockheed Martin produced X-59 is scheduled for its first flights in 2021, while the Boom Technologies XB-1 is expected to fly in 2020.[86] [87] Meanwhile, Aerion Supersonic intends to produce and fly its AS-2 supersonic business jet by 2023, forgoing the process of developing a demonstrator entirely.[88] All of these designs, with the exception of the X-59, will depend upon a repeal of the overland supersonic flight ban before they can enter the market.