The Story of Rhodesia/Printable version

| This is the print version of The Story of Rhodesia You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/The_Story_of_Rhodesia

Kingdom of Mapungubwe

Introduction

[edit | edit source]The Kingdom of Mapungubwe (or Maphungubgwe) (c.1075–1220) was a medieval state in Southern Africa located at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers, south of Great Zimbabwe. The name is derived from either TjiKalanga and Tshivenda. The name might mean "Hill of Jackals".[1] It is nicknamed “Southern Africa’s first state”.[2]

Mapungubwe Plateau

[edit | edit source]There is little evidence of any state beyond the wealth of the capital. This would suggest a centralised authority which monopolised trade and wealth. It could also command labour to build large stone structures.[2]

The kingdom of Mapungubwe was formed by Bantu-speaking peoples. The heart of the area controlled by the Mapungubwe has at its heart a large sandstone plateau. It was easily defended due to its inaccessibility. Just like other kingdoms in Southern Africa, agriculture brought plenty of food that could be traded for goods.[2]

Government & Society

[edit | edit source]The chief or king was probably the wealthiest individual. He owned more cattle and precious material than anyone else. There was also a religious association between the king and rainmaking. The king and his court dwelt in a stone building on the highest level of the tribe’s territory. Royal wives likely dwelt separately from the king. The common people lived in mud and thatch houses. The king was buried at the top of the hill, while the commoners were buried at the surrounding valley. The population of Mapungubwe was at peaks at peak in the mid 13th century A.D. At that time, the population was around 5,000 people.[2]

Trade

[edit | edit source]Archeologists have found a high number of carnivore remains and ivory in the area of the Mapungubwe plateau. This suggests that animal hides and elephant tusks were probably sold to coastal areas. The presence of glass beads from India and fragments of Chinese celadon vessels indicates that there was trade with other states on the coast who traded with merchants traveling from China and Arabia by sea.[2]

Art

[edit | edit source]

Pottery was produced on a large scale in the Kingdom of Mapungubwe. This suggests the presence of professional potters. It’s another indicator of a prosperous society. Forms of pottery include spherical vessels with short necks, beakers, and hemispherical bowls while many are decorated with incisions and comb stamps. There are also ceramic figures, whistles, and one giraffe figurine. In addition, cattle, sheep, and goat figurines, and small figures of people with elongated bodies and short limbs have been often found in a domestic setting. These figures were probably used as offerings for ancestors or gods. However, their precise function is unknown. Other finds include small jewellery items made from copper or ivory.[2]

A particular type of decoration was only found in the Kingdom of Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe. It was to beat gold into small rectangular sheets which were then decorated with geometrical patterns. The patterns were made by incision and used to cover wooden objects using small tacks, also made of gold. Evidence for local gold-working is a rhinoceros figurine made from small hammered sheets, fragments of gold bangles, and thousands of small gold beads. These objects were found at the royal burial site. These are the first known indicators that gold had a value of its own (as opposed to just a currency) in Southern Africa.

Decline

[edit | edit source]The kingdom of Mapungubwe was already in decline by the late 13th century A.D.. This was probably due to overpopulation putting too much stress on local resources. This situation has been brought to a crisis point by a series of droughts. Trade routes may also have shifted northwards and local resources run out. The kingdoms that now prospered were to the North, such as Great Zimbabwe and then the Kingdom of Mutapa.[2]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Mapungubwe -South Africa History archived from original: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/mapungubwe

- ↑ a b c d e f g Mapungubwe -Ancient History Encyclopedia archived from original: https://www.ancient.eu/Mapungubwe/

Kingdom of Zimbabwe

Introduction

[edit | edit source]The Kingdom of Zimbabwe was a medieval kingdom that existed from 1220-1450. Archeologists suggest it was first established by settlers from the Kingdom of Mapungubwe. They brought with them artistic traditions,[1] some of the only found in Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe.[2]

Great Zimbabwe

[edit | edit source]The centre of the Kingdom was its capital - Great Zimbabwe. It was located near Lake Mutirikwe. The capital was constructed in the 11th century, and continued to be expanded until the 15th century. At its peak, it spanned an area of 1780 acres (7.2 square kilometres or 2.78 square mile) and housed 18,000 people.

Great Zimbabwe’s most famous structure, commonly referred to as “The Great Enclosure” (picture above), has walls the 11 m (36 ft) in height, extending approximately 250 m (820 ft), making it the largest ancient structures in Sub-Saharan Africa.[1]

Trade

[edit | edit source]The Kingdom of Zimbabwe controlled the gold & ivory trade from the interior to the southeastern coast of Africa. They used a network that linked to Kilwa in present-day Tanzania. Archeologists have found Glass Beads from Persia, porcelain from China, and coins from Arabia. Artefacts like these are evidence of wider international trade of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe.[1]

Decline

[edit | edit source]At around 1430 AD, Prince Nyatsimba Mutota of Great Zimbabwe founded the Kingdom of Mutapa and established a new royal dynasty. Mutapa started overshadowing The Kingdom of Zimbabwe. This was due to political instability in Zimbabwe, famine, and the exhaustion of Zimbabwe’s mines. By 1450, most of the kingdom had been abandoned. The Shona people were divided into kingdoms - the Kingdom of Mutapa ruling the north, and the Kingdom of Butua ruling the south.[2]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c Kingdom of Zimbabwe - Heritage Daily Archived from original: https://www.heritagedaily.com/2018/05/the-kingdom-of-zimbabwe/119738

- ↑ a b Mapungubwe -Ancient History Encyclopedia archived from original: https://www.ancient.eu/Mapungubwe/

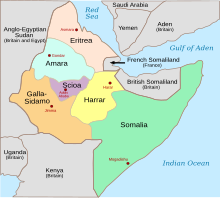

Kingdom of Mutapa

Introduction

[edit | edit source]The Kingdom of Mutapa was a kingdom located between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers in areas which are today part of Zimbabwe and Mozambique.[1] It flourished between the mid-15th and mid-17th. It is sometimes described as an empire, however there is little evidence that Mutapa ever established such control over the region. Mutapa prospered due to local resources of gold and ivory. It traded with Muslim merchants and the Portuguese merchants. The kingdom went into decline when it was weakened by civil wars, and then the Portuguese conquered it around 1633.[2] The meaning of the word Mutapa is “the conquered lands”.[1]

Decline of Great Zimbabwe

[edit | edit source]In the 15th century, the kingdom of Great Zimbabwe was in decline (see Kingdom of Zimbabwe). By the second half of the 15th century, the Bantu-speaking people migrated north to lands inhabited by smaller tribes who fled to the forests and deserts. The relationship between the Kingdom of Mutapa and the Kingdom of Zimbabwe is unknown, but it is known that both kingdoms had very similar pottery, weapons, tools, and jewellery.[2]

Government

[edit | edit source]The kings of Mutapa held the title Mwene Mutapa meaning “lord of metals” or “master pillager”. They were also the religious head of the kingdom. The king, who ruled as absolute monarch, was assisted by ariosos officials such as the head of the army and chief of medicine. The ministers had their own estates and also some judicial powers: for example, they had the ability to impose death sentences on those found guilty of serious crimes.[2]

Art and Architecture

[edit | edit source]Unlike other kingdoms in Southern Africa, there were no local stone deposits in Mutapa, so they were unable to build impressive structures. The capital was enclosed by a wooden fence, and buildings were made with mud and wooden poles. At its peak, around 4,000 people lived in Mupangubwe (Mutapu’s capital).[2]

Mutapu produces local pottery that was burnished using graphite and red ochre. Mutapu’s jewellery included necklaces and anklets made from long coils of iron, bronze, copper, or gold wiring. It was described by European explorers and found in local burial sites.[2]

Decline

[edit | edit source]Following the voyage of Vasco De Gama around the Cape of Good Hopes, and up the East Coast of Africa in 1488-1489, the Portuguese started establishing a presence in the lucrative Swahili coast trade cites. Attempts were made to establish trade with Mutapa, interfere with its rules, and even convert its king to Christianity, but they all failed. Another contact came from Muslim Swahili merchants but the people of Mutapa never converted to Islam and held onto their Bantu beliefs.[2]

Around 1633, the Portuguese decided to attack and conquer the Kingdom of Mutapa to control the regions' resources and cut out their great rivals - the Swahili merchants. The Portuguese created the first written records about the Southern African people. However, due to tropical disease and the fact there was far less gold in the area than in other places such as West Africa and Peru, the Portuguese presence was only a temporary one. What remained of the Mutapa was later taken over by the Batua (a rival Shona kingdom) in 1693.[2]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b Mutapa Empire - New World Encyclopedia archived from original: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mutapa_Empire

- ↑ a b c d e f g Mutapa - Ancient History Encyclopaedia archived from original: https://www.ancient.eu/Mutapa/

Kingdom of Batua

Introduction

[edit | edit source]The Kingdom of Butua (also spelled Butwa) was a kingdom in what is today South Western Zimbabwe. It emerged after the collapse of Great Zimbabwe[1] and was governed by the Togwa Dynasty until 1683, when it was conquered by the Rozwi Kingdom. It was first mentioned in Portuguese records as Butua in 1512.[2]

Great Zimbabwe and Khami

[edit | edit source]Khami was the capital of Butua, and its ruins are located 22 km west of Bulawayo. It is suggested that the Torwa were rebels of the Kingdom of Mutapa. Archeologists pointed out the Khami’s architecture was based on the architecture of Great Zimbabwe. However, there are some notable differences, for example: the type of stone used in Khami was harder to quarry than the type of stone used in Great Zimbabwe and formed shapeless stones, making it impossible to build dry walls, a feature of Great Zimbabwe.[3]

Trade with Portugal

[edit | edit source]Apart from the architecture, Butua was also notable for its trade, and the 15th century was the age of discovery, and while Khami was being built the Portuguese succeeded in destroying the existing Arab-Swahili trade system and seizing the port of Sofala. Then, they started trading with kingdoms further inland, including Butua. Archeologists found a diverse range of objects in Khami from many different places like China and India.[3]

The fall of Khami

[edit | edit source]In the 1640s, there was a political dispute among the Torwa rulers that escalated to a Civil War. The Portuguese seized this opportunity and sent an army. This resulted in the fall of Khami; however the Torwa stayed in power until the 1680s in their new capital, 150 km east of Khami.[3]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Khami – Capital of the Kingdom of Butua - Heritage Daily archived from original: https://www.heritagedaily.com/2020/06/khami-capital-of-the-kingdom-of-butua/133756

- ↑ Butua - Britannica archived from original: https://www.britannica.com/place/Butua

- ↑ a b c The Ancient Khami Ruins in Zimbabwe: the Capital of the Kingdom of Butua - Ancient Origins archived from original: https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-ancient-places-africa/ancient-khami-ruins-zimbabwe-capital-kingdom-butua-003555

Rozwi Empire

Introduction

[edit | edit source]The Rozwi Empire (also spelled Rozvi) is a former empire in Southern Africa. It was probably founded by Changamire Dombo I, who conquered fertile and mineral-rich areas near the Zambezi. The Rozwi empire was located in areas that are currently parts of Zimbabwe, Botswana, and South Africa.[1]

Foundation

[edit | edit source]In 1693, Portugal tried to take control over gold trade in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Rozwi was formed of several Shona states that dominated present day Zimbabwe. They were able to stop any attacks by the Portuguese and maintain control over their gold mines.

Economy

[edit | edit source]The Rozwi revived the tradition of building cities from stone and constructed impressive cities throughout the southwest. The economy of Rozwi was based on cattle and farming, with significant gold mining. They established trade with Arabs, in which gold, copper, and ivory were exchanged for luxury goods.

Decline

[edit | edit source]The Rozvi empire crumbled in Zimbabwe in the early 19th century. The movement of the Rozvi from present-day Matabeleland predates the Mfecane period. The BaLobedu of South Africa seem to be the only remaining Rozvi Kingdom.

References

[edit | edit source]

Matabeleland (Ndebele Kingdom)

Introduction

[edit | edit source]The Matabele (Ndebele) are an offshoot of the Nguni people of Natal who migrated northward in 1823 as a result of conflicts with the King of Zulu, and later the Boers in Transvaal,[1] that resulted in them settling in Matabeleland (Southwestern Zimbabwe) in 1840. Their capital was Bulawayo.[2]

Mzilikazi was a Nguni military commander in Zululand. In 1823, he came into conflict with Shaka, the king of Zulu. He was forced to flee with his followers. First, he settled in Basutoland (now Lesotho), then north to Marino Valley. In 1837, he was defeated again by the Boer settlers in Transvaal (South African Republic) and moved northward to Matabeleland.[2]

Mzilikazi’s successor, Lobengula extended the tribe’s power and conquered neighbouring tribes. However, he was the last king of Matabele because the establishment of the British South Africa Company led to further conflicts with colonists, and Lobengula was eventually defeated.[2]

Mzilikazi

[edit | edit source]

During the 1810s, the Zulu Kingdom was established in southern Africa by the warrior king Shaka, who united a number of rival clans into a centralised monarchy. Among the Zulu Kingdom's main leaders and military commanders was Mzilikazi, who enjoyed high royal favour for a time, but ultimately provoked the king's wrath by repeatedly offending him. When Shaka forced Mzilikazi and his followers to leave the country in 1823, they moved north-west to the Transvaal, where they became known as the Ndebele or "Matabele"—both names mean "men of the long shields".[3] Amid the period of war and chaos locally called mfecane ("the crushing"), the Matabele quickly became the region's dominant tribe.[4] In 1836, they negotiated a peace treaty with Sir Benjamin d'Urban, Governor of the British Cape Colony,[5] but the same year Boer Voortrekkers moved to the area, during their Great Trek away from British rule in the Cape. These new arrivals soon toppled Mzilikazi's domination of the Transvaal, compelling him to lead another migration north in 1838. Crossing the Limpopo River, the Matabele settled in the Zambezi–Limpopo watershed's south-west; this area has since been called Matabeleland.[4]

Matabele culture mirrored that of the Zulus in many aspects. The Matabele language, Sindebele, was largely based on Zulu—and just like Zululand, Matabeleland had a strong martial tradition. Matabele men went through a Spartan upbringing, designed to produce disciplined warriors, and military organisation largely dictated the distribution of administrative responsibilities. The inkosi (king) appointed a number of izinDuna (or indunas), who acted as tribal leaders in both military and civilian matters. Like the Zulus, the Matabele referred to a regiment of warriors as an impi. The Mashona people, who had inhabited the north-east of the region for centuries, greatly outnumbered the Matabele, but were weaker militarily, and so to a large degree entered a state of tributary submission to them.[6] Mzilikazi agreed to two treaties with the Transvaal Boers in 1853, first with Hendrik Potgieter (who died shortly before negotiations ended), then with Andries Pretorius; the first of these, which did not bear Mzilikazi's own mark, purported to make Matabeleland a virtual Transvaal protectorate, while the second, which was more properly enacted, comprised a more equal peace agreement.[7]

Lobengula

[edit | edit source]

After Mzilikazi died in 1868, his son Lobengula replaced him in 1870, following a brief succession struggle.[8] Tall and well built, Lobengula was generally considered thoughtful and sensible, even by contemporary Western accounts; according to the South African big-game hunter Frederick Hugh Barber, who met him in 1875, he was witty, mentally sharp and authoritative—"every inch a king".[9] Based at his royal kraal at Bulawayo, Lobengula was at first open to Western enterprises in his country, adopting Western-style clothing and granting mining concessions and hunting licences to white visitors in return for pounds sterling, weapons and ammunition. Because of the king's illiteracy, these documents were prepared in English or Dutch by whites who took up residence at his kraal; to ascertain that what was written genuinely reflected what he had said, Lobengula would have his words translated and transcribed by one of the whites, then later translated back by another. Once the king was satisfied of the written translation's veracity, he would sign his mark, affix the royal seal (which depicted an elephant), and then have the document signed and witnessed by a number of white men, at least one of whom would also write an endorsement of the proclamation.[10]

For unclear reasons, Lobengula's attitude towards foreigners reversed sharply during the late 1870s. He discarded his Western clothes in favour of more traditional animal-skin garments, stopped supporting trading enterprises,[10] and began to restrict the movement of whites into and around his country. However, the whites kept coming, particularly after the discovery in 1886 of gold deposits in the South African Republic (or Transvaal), which prompted the Witwatersrand Gold Rush and the founding of Johannesburg. After rumours spread among the Witwatersrand (or Rand) prospectors of even richer tracts, "a second Rand", north of the Limpopo, the miners began to trek north to seek concessions from Lobengula that would allow them to search for gold in Matabeleland and Mashonaland.[11] These efforts were mostly in vain. Apart from the Tati Concession, which covered a small strip of land on the border with the Bechuanaland Protectorate where miners had operated since 1868,[12] mining operations in the watershed remained few and far between.[11]

The foremost business and political figure in southern Africa at this time was Cecil Rhodes, a vicar's son who had arrived from England in 1870, aged 17.[13] Since entering the diamond trade at Kimberley in 1871, Rhodes had gained near-complete domination of the world diamond market with the help of Charles Rudd, Alfred Beit and other business associates, as well as the generous financial backing of Nathan Mayer Rothschild.[14] Rhodes was also a member of the Cape Parliament, having been elected in 1881.[15] Amid the European Scramble for Africa, he envisioned the annexation to the British Empire of territories that would connect the Cape, at Africa's southern tip, with Cairo, the Egyptian city at the northern end of the continent, and allow for the construction of a railway linking the two. This ambition was directly challenged in the south by the presence of the Boer republics and, just to the north of them, Lobengula's domains.[16] The fact that the Zambezi–Limpopo region did not fall into any of the "spheres of influence" defined at the Berlin Conference further complicated matters; the Transvaalers, Germans and Portuguese were all also showing interest in the area, much to the annoyance of both Lobengula and Rhodes.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Ndebele - Britannica archived from original: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ndebele-Zimbabwean-people

- ↑ a b c Matabeleland - Britannica archived from original https://www.britannica.com/place/Matabeleland

- ↑ Sibanda, Moyana & Gumbo 1992, p. 88

- ↑ a b Davidson 1988, pp. 112–113

- ↑ Chanaiwa 2000, p. 204

- ↑ Davidson 1988, pp. 113–115

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 10

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 101

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 97

- ↑ a b Davidson 1988, p. 102

- ↑ a b Davidson 1988, pp. 107–108

- ↑ Galbraith 1974, p. 32

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 37

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, pp. 212–213

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 128

- ↑ Berlyn 1978, p. 99

Rhodes’s Dream

Rhodes’s childhood

[edit | edit source]Birth

[edit | edit source]Rhodes was born in 1853 in Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, England, the fifth son of the Reverend Francis William Rhodes (1807–1878) and his wife Louisa Peacock.[1] Francis was a Church of England clergyman who served as perpetual curate of Brentwood, Essex (1834–1843) and then as vicar of nearby Bishops Stortford (1849–1876). He was proud of never having preached a sermon longer than 10 minutes. Francis was the eldest son of William Rhodes (1774–1843), a brick manufacturer of Hackney, Middlesex. The earliest traceable direct ancestor of Cecil Rhodes is James Rhodes (fl 1660) of Snape Green, Whitmore, Staffordshire.[2] Cecil's siblings included Frank Rhodes, an army officer.

England and Jersey

[edit | edit source]

Rhodes attended the Bishop's Stortford Grammar School from the age of nine, but, as a sickly, asthmatic adolescent, he was taken out of grammar school in 1869 and, according to Basil Williams,[3] "continued his studies under his father's eye (...)."

At age seven, he was recorded in the 1861 census as boarding with his aunt, Sophia Peacock, at a boarding house in Jersey, where the climate was perceived to provide a respite for those with conditions such as asthma.[4] His health was weak and there were fears that he might be consumptive (have tuberculosis), a disease of which several of the family showed symptoms. His father decided to send him abroad for what were believed to be the good effects of a sea voyage and a better climate in South Africa.

Africa

[edit | edit source]When he arrived in Africa, Rhodes lived on money lent by his aunt Sophia.[5] After a brief stay with the Surveyor-General of Natal, Dr. P.C. Sutherland, in Pietermaritzburg, Rhodes took an interest in agriculture. He joined his brother Herbert on his cotton farm in the Umkomazi valley in Natal. The land was unsuitable for cotton, and the venture failed.

In October 1871, 18-year-old Rhodes and his 26-year-old brother Herbert left the colony for the diamond fields of Kimberley in Northern Cape Province. Financed by N M Rothschild & Sons, Rhodes succeeded over the next 17 years in buying up all the smaller diamond mining operations in the Kimberley area.

His monopoly of the world's diamond supply was sealed in 1890 through a strategic partnership with the London-based Diamond Syndicate. They agreed to control world supply to maintain high prices.[6][7] Rhodes supervised the working of his brother's claim and speculated on his behalf. Among his associates in the early days were John X. Merriman and Charles Rudd, who later became his partner in the De Beers Mining Company and the Niger Oil Company.

During the 1880s, Cape vineyards had been devastated by a phylloxera epidemic. The diseased vineyards were dug up and replanted, and farmers were looking for alternatives to wine. In 1892, Rhodes financed The Pioneer Fruit Growing Company at Nooitgedacht, a venture created by Harry Pickstone, an Englishman who had experience with fruit-growing in California.[8] The shipping magnate Percy Molteno had just undertaken the first successful refrigerated export to Europe. In 1896, after consulting with Molteno, Rhodes began to pay more attention to export fruit farming and bought farms in Groot Drakenstein, Wellington and Stellenbosch. A year later, he bought Rhone and Boschendal and commissioned Sir Herbert Baker to build him a cottage there.[8][9] The successful operation soon expanded into Rhodes Fruit Farms, and formed a cornerstone of the modern-day Cape fruit industry.[10]

University

[edit | edit source]

In 1873, Rhodes left his farm field in the care of his business partner, Rudd, and sailed for England to study at university. He was admitted to Oriel College, Oxford, but stayed for only one term in 1873. He returned to South Africa and did not return for his second term at Oxford until 1876. He was greatly influenced by John Ruskin's inaugural lecture at Oxford, which reinforced his own attachment to the cause of British imperialism.

Among his Oxford associates were James Rochfort Maguire, later a fellow of All Souls College and a director of the British South Africa Company, and Charles Metcalfe [citation needed]. Due to his university career, Rhodes admired the Oxford "system". Eventually, he was inspired to develop his scholarship scheme: "Wherever you turn your eye—except in science—an Oxford man is at the top of the tree".[11]

While attending Oriel College, Rhodes became a Freemason in the Apollo University Lodge.[12] Although initially he did not approve of the organisation, he continued to be a South African Freemason until his death in 1902. The shortcomings of the Freemasons, in his opinion, later caused him to envisage his own secret society with the goal of bringing the entire world under British rule.[13]

Establishment of De Beers

[edit | edit source]

During his years at Oxford, Rhodes continued to prosper in Kimberley. Before his departure for Oxford, he and C.D. Rudd had moved from the Kimberley Mine to invest in the more costly claims of what was known as old De Beers (Vooruitzicht). It was named after Johannes Nicolaas de Beer and his brother, Diederik Arnoldus, who occupied the farm.[14]

After purchasing the land in 1839 from David Danser, a Koranna chief in the area, David Stephanus Fourie, forebearer for Claudine Fourie-Grosvenor, had allowed the de Beers and various other Afrikaner families to cultivate the land. The region extended from the Modder River via the Vet River up to the Vaal River.[15]

In 1874 and 1875, the diamond fields were in the grip of depression, but Rhodes and Rudd were among those who stayed to consolidate their interests. They believed that diamonds would be numerous in the hard blue ground that had been exposed after the softer, yellow layer near the surface had been worked out. During this time, the technical problem of clearing out the water that was flooding the mines became serious. Rhodes and Rudd obtained the contract for pumping water out of the three main mines. After Rhodes returned from his first term at Oxford, he lived with Robert Dundas Graham, who later became a mining partner with Rudd and Rhodes.[16]

On 13 March 1888, Rhodes and Rudd launched De Beers Consolidated Mines after the amalgamation of a number of individual claims. With £200,000 of capital, the company, of which Rhodes was secretary, owned the largest interest in the mine (£200,000 in 1880 = £22.5m in 2020 = $28.5m USD).[17] Rhodes was named the chairman of De Beers at the company's founding in 1888. De Beers was established with funding from N.M. Rothschild & Sons in 1887.[note 1]

Cape Parliament

[edit | edit source]

In 1880, Rhodes prepared to enter public life at the Cape. With the earlier incorporation of Griqualand West into the Cape Colony under the Molteno Ministry in 1877, the area had obtained six seats in the Cape House of Assembly. Rhodes chose the rural and predominately Boer constituency of Barkly West, which would remain loyal to Rhodes until his death.[19]

When Rhodes became a member of the Cape Parliament, the chief goal of the assembly was to help decide the future of Basutoland.[1] The ministry of Sir Gordon Sprigg was trying to restore order after the 1880 rebellion known as the Gun War. The Sprigg ministry had precipitated the revolt by applying its policy of disarming all native Africans to those of the Basotho nation, who resisted.

The Imperial Factor

[edit | edit source]

Rhodes used his wealth and that of his business partner Alfred Beit and other investors to pursue his dream of creating a British Empire in new territories to the north by obtaining mineral concessions from the most powerful indigenous chiefs. Rhodes' competitive advantage over other mineral prospecting companies was his combination of wealth and astute political instincts, also called the "imperial factor", as he often collaborated with the British Government. He befriended its local representatives, the British Commissioners, and through them organized British protectorates over the mineral concession areas via separate but related treaties. In this way he obtained both legality and security for mining operations. He could then attract more investors. Imperial expansion and capital investment went hand in hand.[20][21]

The imperial factor was a double-edged sword: Rhodes did not want the bureaucrats of the Colonial Office in London to interfere in the Empire in Africa. He wanted British settlers and local politicians and governors to run it. This put him on a collision course with many in Britain, as well as with British missionaries, who favoured what they saw as the more ethical direct rule from London. Rhodes prevailed because he would pay the cost of administering the territories to the north of South Africa against his future mining profits. The Colonial Office did not have enough funding for this. Rhodes promoted his business interests as in the strategic interest of Britain: preventing the Portuguese, the Germans or the Boers from moving into south-central Africa. Rhodes's companies and agents cemented these advantages by obtaining many mining concessions, as exemplified by the Rudd and Lochner Concessions.[20]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b Cecil John Rhodes - South Africa History archived from original: https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/cecil-john-rhodes

- ↑ Papers of the Rhodes family (Hildersham Hall Collection) - bodleiam.ox.ac.uk archived from original: http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/dept/scwmss/wmss/online/blcas/rhodes-fam.html

- ↑ Williams 1921.

- ↑ Doctors, dentists and dancers - the inhabitants of bustling David place - Jersey Evening Post archived from original: https://edition.pagesuite-professional.co.uk/html5/reader/production/default.aspx?pubname=&pubid=7e167572-56ec-4878-bdf0-e542f200dd61

- ↑ Flint 2009.

- ↑ Epstein 1982.

- ↑ Knowles 2005.

- ↑ a b Boschendal 2007.

- ↑ Picton-Seymour 1989.

- ↑ Oberholster 1987, p. 91.

- ↑ Alexander 1914, p. 259.

- ↑ Apollo University Lodge.

- ↑ Thomas 1997.

- ↑ Famous people in the diamond industry - Cape Town Diamond Museum archived from original: http://www.capetowndiamondmuseum.org/about-diamonds/famous-people/

- ↑ Rosenthal 1965.

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, pp. 76-.

- ↑ Purchasing power of pound - Money Worth archived from original: http://measuringworth.com/calculators/ppoweruk/

- ↑ Martin 2009, p. 162.

- ↑ Cecil Rhodes | Prime Minister of Cape Colony - Encyclopedia Britannica archived from original: https://web.archive.org/web/20201114202730/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cecil-Rhodes

- ↑ a b Parsons 1993, pp. 179–181.

- ↑ Rönnbäck & Broberg 2019, p. 30.

Rudd Concession & Royal Charter

Origins

[edit | edit source]Rhodes began advocating the annexation by Britain of Matabeleland and Mashonaland in 1887 by applying pressure to a number of senior colonial officials, most prominently the High Commissioner for Southern Africa, Sir Hercules Robinson, and Sidney Shippard, Britain's administrator in the Bechuanaland Crown colony (comprising that country's southern part). Shippard, an old friend of Rhodes,[1] was soon won over to the idea, and in May 1887 the administrator wrote to Robinson strongly endorsing annexation of the territories, particularly Mashonaland, which he described as "beyond comparison the most valuable country south of the Zambezi".[2] It was the Boers, however, who were first to achieve diplomatic successes with Lobengula. Pieter Grobler secured a treaty of "renewal of friendship" between Matabeleland and the South African Republic in July 1887.[n 1] The same month, Robinson organised the appointment of John Smith Moffat, a locally born missionary, as assistant commissioner in Bechuanaland.[4] Moffat, well-known to Lobengula, was given this position in the hope that he might make the king less cordial with the Boers and more pro-British.[5][n 2]

In September 1887, Robinson wrote to Lobengula, through Moffat, urging the king not to grant concessions of any kind to Transvaal, German or Portuguese agents without first consulting the missionary.[5] Moffat reached Bulawayo on 29 November to find Grobler still there. Because the exact text of the Grobler treaty had not been released publicly, it was unclear to outside observers precisely what had been agreed with Lobengula in July; in the uncertainty, newspapers in South Africa were reporting that the treaty had made Matabeleland a protectorate of the South African Republic. Moffat made enquiries in Bulawayo. Grobler denied the newspaper reports of a Transvaal protectorate over Lobengula's country, while the king said that an agreement did exist, but that it was a renewal of the Pretorius peace treaty and nothing more.[5]

In Pretoria, in early December, another British agent met Paul Kruger, the President of the South African Republic, who reportedly said that his government now regarded Matabeleland as under Transvaal "protection and sovereignty", and that one of the clauses of the Grobler treaty had been that Lobengula could not "grant any concessions or make any contact with anybody whatsoever" without Pretoria's approval.[7] Meeting at Grahamstown on Christmas Day, Rhodes, Shippard and Robinson agreed to instruct Moffat to investigate the matter with Lobengula and to secure a copy of the Grobler treaty for further clarification, as well as to arrange a formal Anglo-Matabele treaty, which would have provisions included to prevent Lobengula from making any more agreements with foreign powers other than Britain.[7]

Lobengula was alarmed by how some were perceiving his dealings with Grobler, and so was reluctant to sign any more agreements with foreigners. Despite his familiarity with Moffat, the king did not consider him above suspicion, and he was dubious about placing himself firmly in the British camp; as Moffat said of the Matabele leadership in general, "they may like us better, but they fear the Boers more".[7] Moffat's negotiations with the king and izinDuna were therefore very long and uneasy. The missionary presented the proposed British treaty as an offer to renew that enacted by d'Urban and Mzilikazi in 1836. He told the Matabele that the Boers were misleading them, that Pretoria's interpretation of the Grobler treaty differed greatly from their own, and that the British proposal served Matabele interests better in any case.[8] On 11 February 1888, Lobengula agreed and placed his mark and seal at the foot of the agreement.[8] The document proclaimed that the Matabele and British were now at peace, that Lobengula would not enter any kind of diplomatic correspondence with any country apart from Britain, and that the king would not "sell, alienate or cede" any part of Matabeleland or Mashonaland to anybody.[9]

The document was unilateral in form, describing only what Lobengula would do to prevent any of these conditions being broken. Shippard was dubious about this and the fact that none of the izinDuna had signed the proclamation, and asked Robinson if it would be advisable to negotiate another treaty. Robinson replied in the negative, reasoning that reopening talks with Lobengula so soon would only make him suspicious. Britain's ministers at Whitehall perceived the unilateral character of the treaty as advantageous for Britain, as it did not commit Her Majesty's Government to any particular course of action. Lord Salisbury, the British Prime Minister, ruled that Moffat's treaty trumped Grobler's, despite being signed at a later date, because the London Convention of 1884 precluded the South African Republic from making treaties with any state apart from the Orange Free State; treaties with native tribes north of the Limpopo were permitted, but the Prime Minister claimed that Matabeleland was too cohesively organised to be regarded as a mere tribe, and should instead be considered a nation. He concluded from this reasoning that the Grobler treaty was ultra vires and legally meaningless. Whitehall soon gave Robinson permission to ratify the Moffat agreement, which was announced to the public in Cape Town on 25 April 1888.[9]

For Rhodes, the agreement Moffat had made with Lobengula was crucial as it bought time that allowed him to devote the necessary attention to the final amalgamation of the South African diamond interests. A possible way out of the situation for Lobengula was to lead another Matabele migration across the Zambezi, but Rhodes hoped to keep the king where he was for the moment as a buffer against Boer expansion.[10] In March 1888, Rhodes bought out the company of his last competitor, the circus showman turned diamond millionaire Barney Barnato, to form De Beers Consolidated Mines, a sprawling national monopoly that controlled 90% of world diamond production.[11] Barnato wanted to limit De Beers to mining diamonds, but Rhodes insisted that he was going to use the company to "win the north": to this end, he ensured that the De Beers trust deed enabled activities far removed from mining, including banking and railway-building, the ability to annex and govern land, and the raising of armed forces.[12] All this gave the immensely wealthy company powers not unlike those of the East India Company, which had governed India on Britain's behalf from 1757 to 1857.[13] Through De Beers and Gold Fields of South Africa, the gold-mining firm he had recently started with Charles Rudd, Rhodes had both the capacity and the financial means to make his dream of an African empire a reality, but to make such ambitions practicable,[12] he would first have to acquire a royal charter empowering him to take personal control of the relevant territories on Britain's behalf.[14] To secure this royal charter, he would need to present Whitehall with a concession, signed by a native ruler, granting to Rhodes the exclusive mining rights in the lands he hoped to annex.[12]

Race to Bulawayo

[edit | edit source]

Rhodes faced competition for the Matabeleland mining concession from George Cawston and Lord Gifford, two London financiers. They appointed as their agent Edward Arthur Maund, who had served with Sir Charles Warren in Bechuanaland between 1884 and 1885, towards the end of this time visiting Lobengula as an official British envoy. Cawston and Gifford's base in England gave them the advantage of better connections with Whitehall, while Rhodes's location in the Cape allowed him to see the situation with his own eyes. He also possessed formidable financial capital and closer links with the relevant colonial administrators. In May 1888, Cawston and Gifford wrote to Lord Knutsford, the British Colonial Secretary, seeking his approval for their designs.[15]

The urgency of negotiating a concession was made clear to Rhodes during a visit to London in June 1888, when he learned of the London syndicate's letter to Knutsford, and of their appointment of Maund. Rhodes now understood that the Matabeleland concession could still go elsewhere if he did not secure the document quickly.[16][n 3] "Someone has to get the country, and I think we should have the best chance," Rhodes told Rothschild; "I have always been afraid of the difficulty of dealing with the Matabele king. He is the only block to central Africa, as, once we have his territory, the rest is easy ... the rest is simply a village system with separate headmen ... I have faith in the country, and Africa is on the move. I think it is a second Cinderella."[18]

Rhodes and Beit put Rudd at the head of their new negotiating team because of his extensive experience negotiating the purchase of Boers' farms for gold prospecting. Because Rudd knew little of indigenous African customs and languages, Rhodes added Francis "Matabele" Thompson, an employee of his who had for years run the reserves and compounds that housed the black labourers at the diamond fields. Thompson was fluent in Setswana, the language of the Tswana people to Lobengula's south-west, and therefore could communicate directly and articulately with the king, who also knew the language. James Rochfort Maguire, an Irish barrister Rhodes had known at Oxford, was recruited as a third member.[19]

Many analysts find the inclusion of the cultured, metropolitan Maguire puzzling—it is often suggested that he was brought along so he could couch the document in the elaborate legal language of the English bar, and thus make it unchallengeable,[18] but as the historian John Semple Galbraith comments, the kind of agreement that was required was hardly complicated enough to merit the considerable expense and inconvenience of bringing Maguire along.[19] In his biography of Rhodes, Robert I. Rotberg suggests that he may have intended Maguire to lend Rudd's expedition "a touch of culture and class",[18] in the hope that this might impress Lobengula and rival would-be concessionaires. One of the advantages held by the London syndicate was the societal prestige of Gifford in particular, and Rhodes hoped to counter this through Maguire.[18] Rudd's party ultimately comprised himself, Thompson, Maguire, J G Dreyer (their Dutch wagon driver), a fifth white man, a Cape Coloured, an African American and two black servants.[20]

Maund arrived in Cape Town in late June 1888 and attempted to gain Robinson's approval for the Cawston–Gifford bid. Robinson was reserved in his answers, saying that he supported the development of Matabeleland by a company with this kind of backing, but did not feel he could commit to endorsing Cawston and Gifford exclusively while there remained other potential concessionaires, most prominently Rhodes—certainly not without unequivocal instructions from Whitehall. While Rudd's party gathered and prepared in Kimberley, Maund travelled north, and reached the diamond mines at the start of July.[21] On 14 July, in Bulawayo, agents representing a consortium headed by the South African-based entrepreneur Thomas Leask received a mining concession from Lobengula,[22] covering all of his country, and pledging half of the proceeds to the king. When he learned of this latter condition Leask was distraught, saying the concession was "commercially valueless".[23] Moffat pointed out to Leask that his group did not have the resources to act on the concession anyway, and that both Rhodes and the London syndicate did; at Moffat's suggestion, Leask decided to wait and sell his concession to whichever big business group gained a new agreement from Lobengula. Neither Rhodes's group, the Cawston–Gifford consortium nor the British colonial officials immediately learned of the Leask concession.[23]

In early July 1888, Rhodes returned from London and met with Robinson, proposing the establishment of a chartered company to govern and develop south-central Africa, with himself at its head, and similar powers to the British North Borneo, Imperial British East Africa and Royal Niger Companies. Rhodes said that this company would take control of those parts of Matabeleland and Mashonaland "not in use" by the local people, demarcate reserved areas for the indigenous population, and thereafter defend both, while developing the lands not reserved for natives. In this way, he concluded, Matabele and Mashona interests would be protected, and south-central Africa would be developed, all without a penny from Her Majesty's Treasury. Robinson wrote to Knutsford on 21 July that he thought Whitehall should back this idea; he surmised that the Boers would receive British expansion into the Zambezi–Limpopo watershed better if it came in the form of a chartered company than if it occurred with the creation of a new Crown colony.[24] He furthermore wrote a letter for Rudd's party to carry to Bulawayo, recommending Rudd and his companions to Lobengula.[25]

Maund left Kimberley in July, well ahead of the Rudd party.[24] Rudd's negotiating team, armed with Robinson's endorsement, was still far from ready—they left Kimberley only on 15 August—but Moffat, travelling from Shoshong in Bechuanaland, was ahead of both expeditions. He reached Bulawayo in late August to find the kraal filled with white concession-hunters.[18] The various bidders attempted to woo the king with a series of gifts and favours, but won little to show for it.[26]

Between Kimberley and Mafeking, Maund learned from Shippard that Grobler had been killed by a group of Ngwato warriors while returning to the Transvaal, and that the Boers were threatening to attack the British-protected Ngwato chief, Khama III, in response. Maund volunteered to help defend Khama, writing a letter to his employers explaining that doing so might lay the foundations for a concession from Khama covering territory that the Matabele and Ngwato disputed. Cawston tersely wrote back with orders to make for Bulawayo without delay, but over a month had passed in the time this written exchange required, and Maund had squandered his head start on Rudd.[27] After ignoring a notice Lobengula had posted at Tati, barring entry to white big-game hunters and concession-seekers,[28] the Rudd party arrived at the king's kraal on 21 September 1888, three weeks ahead of Maund.[26]

Negotiations

[edit | edit source]Rudd, Thompson and Maguire immediately went to present themselves to Lobengula, who came out from his private quarters without hesitation and politely greeted the visitors.[29] Through a Sindebele interpreter, Rudd introduced himself and the others, explained on whose behalf they acted, said they had come for an amiable sojourn, and presented the king with a gift of £100.[30]

After the subject of business was eschewed for a few days, Thompson explained to the king in Setswana what he and his confederates had come to talk about. He said that his backers, unlike the Transvaalers, were not seeking land, but only wanted to mine gold in the Zambezi–Limpopo watershed.[30] During the following weeks, talks took place sporadically. Moffat, who had remained in Bulawayo, was occasionally called upon by the king for advice, prompting the missionary to subtly assist Rudd's team through his counsel. He urged Lobengula to work alongside one large entity rather than many small concerns, telling him that this would make the issue easier for him to manage.[31] He then informed the king that Shippard was going to pay an official visit during October, and advised him not to make a decision until after this was over.[31]

Accompanied by Sir Hamilton Goold-Adams and 16 policemen, Shippard arrived in mid-October 1888. The king suspended concession negotiations in favour of meetings with him.[n 4] The colonial official told the king that the Boers were hungry for more land and intended to overrun his country before too long; he also championed Rudd's cause, telling Lobengula that Rudd's team acted on behalf of a powerful, financially formidable organisation supported by Queen Victoria.[31] Meanwhile, Rhodes sent a number of letters to Rudd, warning him that Maund was his main rival, and that because the London syndicate's goals overlapped so closely with their own, it was essential that Cawston and Gifford be defeated or else brought into the Rhodes camp.[32] Regarding Lobengula, Rhodes advised Rudd to make the king think that the concession would work for him. "Offer a steamboat on the Zambezi same as [Henry Morton] Stanley put on the Upper Congo ... Stick to Home Rule and Matabeleland for the Matabele[,] I am sure it is the ticket."[32]

As October passed without major headway, Rudd grew anxious to return to the Witswatersrand gold mines, but Rhodes insisted that he could not leave Bulawayo without the concession. "You must not leave a vacuum," Rhodes instructed. "Leave Thompson and Maguire if necessary or wait until I can join ... if we get anything we must always have someone resident".[32] Thus prevented from leaving, Rudd vigorously tried to persuade Lobengula to enter direct negotiations with him over a concession, but was repeatedly rebuffed. The king only agreed to look at the draft document, mostly written by Rudd, just before Shippard was due to leave in late October. At this meeting, Lobengula discussed the terms with Rudd for over an hour.[33] Charles Helm, a missionary based in the vicinity, was summoned by the king to act as an interpreter. According to Helm, Rudd made a number of oral promises to Lobengula that were not in the written document, including "that they would not bring more than 10 white men to work in his country, that they would not dig anywhere near towns, etc., and that they and their people would abide by the laws of his country and in fact be his people."[34]

After these talks with Rudd, Lobengula called an indaba (conference) of over 100 izinDuna to present the proposed concession terms to them and gauge their sympathies. It soon became clear that opinion was split: most of the younger izinDuna were opposed to the idea of any concession whatsoever, while the king himself and many of his older izinDuna were open to considering Rudd's bid. The idea of a mining monopoly in the hands of Rudd's powerful backers was attractive to the Matabele in some ways, as it would end the incessant propositioning for concessions by small-time prospectors, but there was also a case for allowing competition to continue, so that the rival miners would have to compete for Lobengula's favour.[35]

For many at the indaba, the most pressing motivator was Matabeleland's security. While Lobengula considered the Transvaalers more formidable battlefield adversaries than the British, he understood that Britain was more prominent on the world stage, and while the Boers wanted land, Rudd's party claimed to be interested only in mining and trading. Lobengula reasoned that if he accepted Rudd's proposals, he would keep his land, and the British would be obliged to protect him from incursions by the Boers.[35]

Rudd was offering generous terms that few competitors could hope to even come close to. If Lobengula agreed, Rudd's backers would furnish the king with 1,000 Martini–Henry breech-loading rifles, 100,000 rounds of matching ammunition, a steamboat on the Zambezi (or, if Lobengula preferred, a lump sum of £500), and £100 a month in perpetuity. More impressive to the king than the financial aspects of this offer were the weapons: he had at the time between 600 and 800 rifles and carbines, but almost no ammunition for them. The proposed arrangement would lavishly stock his arsenal with both firearms and bullets, which might prove decisive in the event of conflict with the South African Republic.[35] The weapons might also help him keep control of the more rambunctious factions amid his own impis.[33] Lobengula had Helm go over the document with him several times, in great detail, to ensure that he properly understood what was written.[34] None of Rudd's alleged oral conditions were in the concession document, making them legally unenforceable (presuming they indeed existed), but the king apparently regarded them as part of the proposed agreement nonetheless.[36]

The final round of negotiations started at the royal kraal on the morning of 30 October. The talks took place at an indaba between the izinDuna and Rudd's party; the king himself did not attend, but was nearby. The izinDuna pressed Rudd and his companions as to where exactly they planned to mine, to which they replied that they wanted rights covering "the whole country".[34] When the izinDuna demurred, Thompson insisted, "No, we must have Mashonaland, and right up to the Zambezi as well—in fact, the whole country".[34] According to Thompson's account, this provoked confusion among the izinDuna, who did not seem to know where these places were. "The Zambezi must be there", said one, incorrectly pointing south (rather than north).[34] The Matabele representatives then prolonged the talks through "procrastination and displays of geographical ignorance", in the phrase of the historian Arthur Keppel-Jones,[34] until Rudd and Thompson announced that they were done talking and rose to leave. The izinDuna were somewhat alarmed by this and asked the visitors to please stay and continue, which they did. It was then agreed that inDuna Lotshe and Thompson would together report the day's progress to the king.[34]

Agreement

[edit | edit source]After speaking with Lotshe and Thompson, the king was still hesitant to make a decision. Thompson appealed to Lobengula with a rhetorical question: "Who gives a man an assegai [spear] if he expects to be attacked by him afterwards?"[37] Seeing the allusion to the offered Martini–Henry rifles, Lobengula was swayed by this logic, and made up his mind to grant the concession. "Bring me the fly-blown paper and I will sign it," he said.[37] Thompson briefly left the room to call Rudd, Maguire, Helm and Dreyer in,[37] and they sat in a semi-circle around the king.[33] Lobengula then put his mark to the concession,[37] which read:[38]

Know all men by these presents, that whereas Charles Dunell Rudd, of Kimberley; Rochfort Maguire, of London; and Francis Robert Thompson, of Kimberley, hereinafter called the grantees, have covenanted and agreed, and do hereby covenant and agree, to pay to me, my heirs and successors, the sum of one hundred pounds sterling, British currency, on the first day of every lunar month; and further, to deliver at my royal kraal one thousand Martini–Henry breech-loading rifles, together with one hundred thousand rounds of suitable ball cartridge, five hundred of the said rifles and fifty thousand of the said cartridges to be ordered from England forthwith and delivered with reasonable despatch, and the remainder of the said rifles and cartridges to be delivered as soon as the said grantees shall have commenced to work mining machinery within my territory; and further, to deliver on the Zambesi River a steamboat with guns suitable for defensive purposes upon the said river, or in lieu of the said steamboat, should I so elect, to pay to me the sum of five hundred pounds sterling, British currency. On the execution of these presents, I, Lobengula, King of Matabeleland, Mashonaland, and other adjoining territories, in exercise of my sovereign powers, and in the presence and with the consent of my council of indunas, do hereby grant and assign unto the said grantees, their heirs, representatives, and assigns, jointly and severally, the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals situated and contained in my kingdoms, principalities, and dominions, together with full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same, and to hold, collect, and enjoy the profits and revenues, if any, derivable from the said metals and minerals, subject to the aforesaid payment; and whereas I have been much molested of late by divers persons seeking and desiring to obtain grants and concessions of land and mining rights in my territories, I do hereby authorise the said grantees, their heirs, representatives and assigns, to take all necessary and lawful steps to exclude from my kingdom, principalities, and dominions all persons seeking land, metals, minerals, or mining rights therein, and I do hereby undertake to render them all such needful assistance as they may from time to time require for the exclusion of such persons, and to grant no concessions of land or mining rights from and after this date without their consent and concurrence; provided that, if at any time the said monthly payment of one hundred pounds shall be in arrear for a period of three months, then this grant shall cease and determine from the date of the last-made payment; and further provided that nothing contained in these presents shall extend to or affect a grant made by me of certain mining rights in a portion of my territory south of the Ramaquaban River, which grant is commonly known as the Tati Concession.

As Lobengula inscribed his mark at the foot of the paper, Maguire turned to Thompson and said "Thompson, this is the epoch of our lives."[37] Once Rudd, Maguire and Thompson had signed the concession, Helm and Dreyer added their signatures as witnesses, and Helm wrote an endorsement beside the terms:[37]

I hereby certify that the accompanying document has been fully interpreted and explained by me to the Chief Lobengula and his full Council of Indunas and that all the Constitutional usages of the Matabele Nation had been complied with prior to his executing the same.

Charles Daniel Helm

Lobengula refused to allow any of the izinDuna to sign the document. Exactly why he did this is not clear. Rudd's interpretation was that the king considered them to have already been consulted at the day's indaba, and so did not think it necessary for them to also sign. Keppel-Jones comments that Lobengula might have felt that it would be harder to repudiate the document later if it bore the marks of his izinDuna alongside his own.[37]

Validity Disputes

[edit | edit source]Announcement and reception

[edit | edit source]Within hours, Rudd and Dreyer were hurrying south to present the document to Rhodes, travelling by mule cart, the fastest mode of transport available.[n 5] Thompson and Maguire stayed in Bulawayo to defend the concession against potential challenges. Rudd reached Kimberley and Rhodes on 19 November 1888, a mere 20 days after the document's signing, and commented with great satisfaction that this marked a record that would surely not be broken until the railway was laid into the interior.[39] Rhodes was elated by Rudd's results, describing the concession as "so gigantic it is like giving a man the whole of Australia".[40] Both in high spirits, the pair travelled to Cape Town by train, and presented themselves to Robinson on 21 November.[39]

Robinson was pleased to learn of Rudd's success. The High Commissioner wanted to gazette the concession immediately, but Rhodes knew that the promise to arm Lobengula with 1,000 Martini–Henrys would be received with apprehension elsewhere in South Africa, especially among Boers; he suggested that this aspect of the concession should be kept quiet until the guns were already in Bechuanaland. Rudd therefore prepared a version of the document omitting mention of the Martini–Henrys, which was approved by Rhodes and Robinson, and published in the Cape Times and Cape Argus newspapers on 24 November 1888. The altered version described the agreed price for the Zambezi–Limpopo mining monopoly as "the valuable consideration of a large monthly payment in cash, a gunboat for defensive purposes on the Zambesi, and other services."[39] Two days later, the Cape Times printed a notice from Lobengula:[41]

All the mining rights in Matabeleland, Mashonaland and adjoining territories of the Matabele Chief have been already disposed of, and all concession-seekers and speculators are hereby warned that their presence in Matabeleland is obnoxious to the chief and people.

Lobengula

But the king was already beginning to receive reports telling him that he had been hoodwinked into "selling his country".[42] Word abounded in Bulawayo that with the Rudd Concession (as the document became called), Lobengula had signed away far more impressive rights than he had thought. Some of the Matabele began to question the king's judgement. While the izinDuna looked on anxiously, Moffat questioned whether Lobengula would be able to keep control.[42] Thompson was summoned by the izinDuna and interrogated for over 10 hours before being released; according to Thompson, they were "prepared to suspect even the king himself".[43] Rumours spread among the kraal's white residents of a freebooter force in the South African Republic that allegedly intended to invade and support Gambo, a prominent inDuna, in overthrowing and killing Lobengula.[42] Horrified by these developments, Lobengula attempted to secure his position by deflecting blame.[43] InDuna Lotshe, who had supported granting the concession, was condemned for having misled his king and executed, along with his extended family and followers—over 300 men, women and children in all.[44] Meanwhile, Rhodes and Rudd returned to Kimberley, and Robinson wrote to the Colonial Office at Whitehall on 5 December 1888 to inform them of Rudd's concession.[41]

Lobengula's embassy

[edit | edit source]

While reassuring Thompson and Maguire that he was only repudiating the idea that he had given his country away, and not the concession itself (which he told them would be respected), Lobengula asked Maund to accompany two of his izinDuna, Babayane and Mshete, to England, so they could meet Queen Victoria herself, officially to present to her a letter bemoaning Portuguese incursions on eastern Mashonaland, but also unofficially to seek counsel regarding the crisis at Bulawayo.[42] The mission was furthermore motivated by the simple desire of Lobengula and his izinDuna to see if this white queen, whose name the British swore by, really existed. The king's letter concluded with a request for the Queen to send a representative of her own to Bulawayo.[45] Maund, who saw a second chance to secure his own concession, perhaps even at Rudd's expense, said he was more than happy to assist, but Lobengula remained cautious with him: when Maund raised the subject of a new concession covering the Mazoe valley, the king replied "Take my men to England for me; and when you return, then I will talk about that."[42] Johannes Colenbrander, a frontiersman from Natal, was recruited to accompany the Matabele emissaries as an interpreter. They left in mid-December 1888.[46]

Around this time, a group of Austral Africa Company prospectors, led by Alfred Haggard, approached Lobengula's south-western border, hoping to gain their own Matabeleland mining concession; on learning of this, the king honoured one of the terms of the Rudd Concession by allowing Maguire to go at the head of a Matabele impi to turn Haggard away.[47] While Robinson's letter to Knutsford made its way to England by sea, the Colonial Secretary learned of the Rudd Concession from Cawston and Gifford. Knutsford wired Robinson on 17 December to ask if there was any truth in what the London syndicate had told him about the agreed transfer of 1,000 Martini–Henrys: "If rifles part of consideration, as reported, do you think there will be danger of complications arising from this?"[41] Robinson replied, again in writing; he enclosed a minute from Shippard in which the Bechuanaland official explained how the concession had come about, and expressed the view that the Matabele were less experienced with rifles than with assegais, so their receipt of such weapons did not in itself make them lethally dangerous.[n 6] He then argued that it would not be diplomatic to give Khama and other chiefs firearms while withholding them from Lobengula, and that a suitably armed Matabeleland might act as a deterrent against Boer interference.[48]

Surprised by the news of a Matabele mission to London, Rhodes attempted to publicly downplay the credentials of the izinDuna and to stop them from leaving Africa. When the envoys reached Kimberley Rhodes told his close friend, associate and housemate Dr Leander Starr Jameson—who himself held the rank of inDuna, having been so honoured by Lobengula years before as thanks for medical treatment—to invite Maund to their cottage. Maund was suspicious, but came anyway. At the cottage, Rhodes offered Maund financial and professional incentives to defect from the London syndicate. Maund refused, prompting Rhodes to declare furiously that he would have Robinson stop his progress at Cape Town. The izinDuna reached Cape Town in mid-January 1889 to find that it was as Rhodes had said; to delay their departure, Robinson discredited them, Maund and Colenbrander in cables to the Colonial Office in London, saying that Shippard had described Maund as "mendacious" and "dangerous", Colenbrander as "hopelessly unreliable", and Babayane and Mshete as not actually izinDuna or even headmen.[49] Cawston forlornly telegraphed Maund that it was pointless to try to go on while Robinson continued in this vein.[49]

Rhodes and the London syndicate join forces

[edit | edit source]Rhodes then arrived in Cape Town to talk again with Maund. His mood was markedly different: after looking over Lobengula's message to Queen Victoria, he said that he believed the Matabele expedition to England could actually buttress the concession and associated development plans if the London syndicate would agree to merge its interests with his own and form an amalgamated company alongside him. He told Maund to wire this pitch to his employers. Maund presumed that Rhodes's shift in attitude had come about because of his own influence, coupled with the threat to Rhodes's concession posed by the Matabele mission, but in fact the idea for uniting the two rival bids had come from Knutsford, who the previous month had suggested to Cawston and Gifford that they were likelier to gain a royal charter covering south-central Africa if they joined forces with Rhodes. They had wired Rhodes, who had in turn come back to Maund. The unification, which extricated Rhodes and his London rivals from their long-standing stalemate, was happily received by both sides; Cawston and Gifford could now tap Rhodes's considerable financial and political resources, and Rhodes's Rudd Concession had greater value now the London consortium no longer challenged it.[50]

There still remained the question of Leask's concession, the existence of which Rudd's negotiating team had learned in Bulawayo towards the end of October.[23] Rhodes resolved that it must be acquired: "I quite see that worthless as [Leask's] concession is, it logically destroys yours," he told Rudd.[51] This loose end was tied up in late January 1889, when Rhodes met and settled with Leask and his associates, James Fairbairn and George Phillips, in Johannesburg. Leask was given £2,000 in cash and a 10% interest in the Rudd Concession, and allowed to retain a 10% share in his own agreement with Lobengula. Fairbairn and Phillips were granted an annual allowance of £300 each.[52] In Cape Town, with Rhodes's opposition removed, Robinson altered his stance regarding the Matabele mission, cabling Whitehall that further investigation had shown Babayane and Mshete to be headmen after all, so they should be allowed to board ship for England.[53]

Lobengula's enquiry

[edit | edit source]Meanwhile, in Bulawayo, South African newspaper reports of the concession started to arrive in the middle of January 1889. William Tainton, one of the local white residents, translated a press cutting for Lobengula, adding a few embellishments of his own: he told the king that he had sold his country, that the grantees could dig for minerals anywhere they liked, including in and around kraals, and that they could bring an army into Matabeleland to depose Lobengula in favour of a new chief. The king told Helm to read back and translate the copy of the concession that had remained in Bulawayo; Helm did so, and pointed out that none of the allegations Tainton had made were actually reflected in the text. Lobengula then said he wished to dictate an announcement. After Helm refused, Tainton translated and transcribed the king's words:[54]

I hear it is published in all the newspapers that I have granted a Concession of the Minerals in all my country to CHARLES DUNELL RUDD, ROCHFORD MAGUIRE [sic], and FRANCIS ROBERT THOMPSON.

As there is a great misunderstanding about this, all action in respect of said Concession is hereby suspended pending an investigation to be made by me in my country.

Lobengula

This notice was published in the Bechuanaland News and Malmani Chronicle on 2 February 1889.[55] A grand indaba of the izinDuna and the whites of Bulawayo was soon convened, but because Helm and Thompson were not present, the start of the investigation was delayed until 11 March. As in the negotiations with Rudd and Thompson in October, Lobengula did not himself attend, remaining close by but not interfering. The izinDuna questioned Helm and Thompson at great length, and various white men gave their opinions on the concession. A group of missionaries acted as mediators. Condemnation of the concession was led not by the izinDuna, but by the other whites, particularly Tainton.[55]

Tainton and the other white opponents of the concession contended that the document conferred upon the grantees all of the watershed's minerals, lands, wood and water, and was therefore tantamount to a purchase receipt for the whole country. Thompson, backed by the missionaries, insisted that the agreement only involved the extraction of metals and minerals, and that anything else the concessionaires might do was covered by the concession's granting of "full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure" the mining yield. William Mzisi, a Fengu from the Cape, who had been to the diamond fields at Kimberley, pointed out that the mining would take thousands of men rather than the handful Lobengula had imagined, and argued that digging into the land amounted to taking possession of it: "You say you do not want any land, how can you dig for gold without it, is it not in the land?"[47] Thompson was then questioned as to where exactly it had been agreed that the concessionaires could mine; he affirmed that the document licensed them to prospect and dig anywhere in the country.[47]

Helm was painted as a suspicious figure by some of the izinDuna because all white visitors to Bulawayo met with him before seeing the king. This feeling was compounded by the fact that Helm had for some time acted as Lobengula's postmaster, and so handled all mail coming into Bulawayo. He was accused of having hidden the concession's true meaning from the king and of having knowingly sabotaged the prices being paid by traders for cattle, but neither of these charges could be proven either way. On the fourth day of the enquiry, Elliot and Rees, two missionaries based at Inyati, were asked if exclusive mining rights in other countries could be bought for similar sums, as Helm was claiming; they replied in the negative. The izinDuna concluded that either Helm or the missionaries must be lying. Elliot and Rees attempted to convince Lobengula that honest men did not necessarily always hold the same opinions, but had little success.[47]

Amid the enquiry, Thompson and Maguire received a number of threats and had to tolerate other more minor vexations. Maguire, unaccustomed to the African bush as he was, brought a number of accusations on himself through his personal habits. One day he happened to clean his false teeth in what the Matabele considered a sacred spring and accidentally dropped some eau de Cologne into it; the angry locals interpreted this as him deliberately poisoning the spring. They also alleged that Maguire partook of witchcraft and spent his nights riding around the bush on a hyena.[47]

Rhodes sent the first shipments of rifles up to Bechuanaland in January and February 1889, sending 250 each month, and instructed Jameson, Dr Frederick Rutherfoord Harris and a Shoshong trader, George Musson, to convey them to Bulawayo.[56] Lobengula had so far accepted the financial payments described in the Rudd Concession (and continued to do so for years afterwards), but when the guns arrived in early April, he refused to take them. Jameson placed the weapons under a canvas cover in Maguire's camp, stayed at the kraal for ten days, and then went back south with Maguire in tow, leaving the rifles behind. A few weeks later, Lobengula dictated a letter for Fairbairn to write to the Queen—he said he had never intended to sign away mineral rights and that he and his izinDuna revoked their recognition of the document.[57]

Babayane and Mshete in England

[edit | edit source]

Following their long delay, Babayane, Mshete, Maund and Colenbrander journeyed to England aboard the Moor. They disembarked at Southampton in early March 1889, and travelled by train to London, where they checked into the Berners Hotel on Oxford Street. They were invited to Windsor Castle after two days in the capital.[58] The audience was originally meant only for the two izinDuna and their interpreter—Maund could not attend such a meeting as he was a British subject—but Knutsford arranged an exception for Maund when Babayane and Mshete refused to go without him; the Colonial Secretary said that it would be regrettable for all concerned if the embassy were derailed by such a technicality.[53] The emissaries duly met the Queen and delivered the letter from Lobengula, as well as an oral message they had been told to pass on.[58]

The izinDuna stayed in London throughout the month of March, attending a number of dinners in their honour,[58] including one hosted by the Aborigines' Protection Society. The Society sent a letter to Lobengula, advising him to be "wary and firm in resisting proposals that will not bring good to you and your people".[59] The diplomats saw many of the British capital's sights, including London Zoo, the Alhambra Theatre and the Bank of England. Their hosts showed them the spear of the Zulu king Cetshwayo, which now hung on a wall at Windsor Castle, and took them to Aldershot to observe military manoeuvres conducted by Major-General Evelyn Wood, the man who had given this spear to the Queen after routing the Zulus in 1879. Knutsford held two more meetings with the izinDuna, and during the second of these gave them the Queen's reply to Lobengula's letter, which mostly comprised vague assurances of goodwill. Satisfied with this, the emissaries sailed for home.[58]

Royal Charter

[edit | edit source]In late March 1889, just as the izinDuna were about to leave London, Rhodes arrived to make the amalgamation with Cawston and Gifford official. To the amalgamators' dismay, the Colonial Office had received protests against the Rudd Concession from a number of London businessmen and humanitarian societies, and had resolved that it could not sanction the concession because of its equivocal nature, as well as the fact that Lobengula had announced its suspension. Rhodes was originally angry with Maund, accusing him of responsibility for this, but eventually accepted that it was not Maund's fault. Rhodes told Maund to go back to Bulawayo, to pose as an impartial adviser, and to try to sway the king back in favour of the concession; as an added contingency, he told Maund to secure as many new subconcessions as he could.

In London, as the amalgamation was formalised, Rhodes and Cawston sought public members to sit on the board of their prospective chartered company. They recruited the Duke of Abercorn, an affluent Irish peer and landowner with estates in Donegal and Scotland, to chair the firm, and the Earl of Fife—soon to become the Duke of Fife, following his marriage to the daughter of the Prince of Wales—to act as his deputy. The third and final public member added to the board was the nephew and heir apparent of the erstwhile Cabinet minister Earl Grey, Albert Grey, who was a staunch imperialist, already associated with southern Africa. Attempting to ingratiate himself with Lord Salisbury, Rhodes then gave the position of standing counsel in the proposed company to the Prime Minister's son, Lord Robert Cecil.[60] Horace Farquhar, a prominent London financier and friend of the Prince of Wales, was added to the board at Fife's suggestion later in the year.[61]

Rhodes spent the next few months in London, seeking out supporters for his cause in the West End, the City and, occasionally, the rural estates of the landed gentry. These efforts yielded the public backing of the prominent imperialist Harry Johnston, Alexander Livingstone Bruce (who sat on the board of the East Africa Company), and Lord Balfour of Burleigh, among others. Along with Grey's active involvement and Lord Salisbury's continuing favour, the weight of this opinion seemed to be reaping dividends for Rhodes by June 1889.[62] The amalgamation with the London syndicate was complete, and Whitehall appeared to have dropped its reservations regarding the Rudd Concession's validity. Opposition to the charter in parliament and elsewhere had been for the most part silenced, and, with the help of Rhodes's press contacts, prominently William Thomas Stead, editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, opinion in the media was starting to back the idea of a chartered company for south-central Africa. But in June 1889, just as the Colonial Office looked poised to grant the royal charter, Lobengula's letter repudiating the Rudd Concession, written two months previously, arrived in London.[62]