History of video games/Print version/Standardized platforms

| This is the print version of History of video games You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

- Standardized platforms

Timeline

[edit | edit source]Foundational Developments

[edit | edit source]On March 7th 1876 Alexander Graham Bell received a patent for the Telephone,[1][2] sparking a telecommunication revolution by allowing people to talk to one another near instantly over long distances.

In 1966 inventor George Sweigert patents the cordless telephone,[3] laying the groundwork to take telephones on the go.

Many early game pioneers, such as Steve Wozniak, were also telephone phreakers.[4]

-

Alexander Graham Bell operating a long distance telephone in 1892.

-

George Sweigert, inventor of the full duplex cordless telephone.

-

A Blue Box built by Steve Wozniak to Phreak.

1990's

[edit | edit source]1993

[edit | edit source]In 1993 the Siemens S1 phone is released, including a clone of Tetris named Klotz, but is hidden as an easter egg to dodge patent issues.[5]

1994

[edit | edit source]The IBM Simon touchscreen smartphone is released to consumers on August 16, 1994 at a cost of $1,100, lasting six months on the market and selling 50,000 phones.[6] This phone included a puzzle game called Scramble.[7]

Also released in 1994 is the MT-2000 phone by Danish company Hagenuk, which included a variant of Tetris.[7][8]

1997

[edit | edit source]Nokia includes Snake for the first time on the Nokia 6110, a very popular game being included in 400 million devices as of 2013, and which was also among the first multiplayer phone games due to it's two player support over inferred.[9]

2000's

[edit | edit source]On October 7th, 2003 the gaming focused Nokia N-Gage launches.[10]

By the end of the decade the Apple App Store becomes a widely used platform for downloading games on iPhones.[11]

2010's

[edit | edit source]2016

[edit | edit source]Pokémon Go

[edit | edit source]In 2016 Pokémon Go became a widely popular augmented reality game.

-

People playing a multiplayer game on their smartphones.

-

People playing Pokemon Go in 2016.

-

Pokemon Go Plus, a companion device for Pokemon Go players

2019

[edit | edit source]Apple launched Apple Arcade on September 19th, 2019.[12]

Notable Games

[edit | edit source]- Angry Birds

- Fruit Ninja

- Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp

- Fire Emblem Heros

- Candy Crush Saga

- Subway Surfers

- Fortnite

- Temple Run

- Monument Valley

- Fate Grand Order

- Neko Atsume

- Snake

- Part Time UFO

- Send Me To Heaven

- Rhythm Thief & the Paris Caper

- PUBG MOBILE

- 4 Pics 1 Word / 4 Bilder 1 Wort[13]

- Ace Combat Xi: Skies of Incursion

Pokémon Go

[edit | edit source]This game prompted some interest in urban design.[14]

Flappy Bird

[edit | edit source]Became a phenomenon in 2014, then was pulled from app stores by its creator at the peak of its popularity.[15]

Rebel Inc.

[edit | edit source]A counterinsurgency simulator. In 2020 it's developers received assistance from the Afghan Embassy in London, including comment from then Ambassador H.E. Said T. Jawad.[16]

Console Phone Hybrids

[edit | edit source]Many Microconsoles and hybrid consoles made after 2000 use mobile chipsets due to their low cost, integrated features, and low heat.

Consoles with integrated mobile internet

[edit | edit source]- Zeebo (3G)

- PlayStation Vita (3G version only)

Evolution of Smartphones

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Alexander Graham Bell". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "Studying Sound: Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922)- Hear My Voice Albert H. Small Documents Gallery Smithsonian's National Museum of American History". americanhistory.si.edu. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Cordless Phone". liGo Magazine. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ Lapsley, Phil (20 February 2013). "The Definitive Story of Steve Wozniak, Steve Jobs, and Phone Phreaking" (in en). The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/02/the-definitive-story-of-steve-wozniak-steve-jobs-and-phone-phreaking/273331/.

- ↑ "The History of Mobile Video Games: Part One of Three". Exaud. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ "First Smartphone Turns 20: Fun Facts About Simon". Time. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ a b V, Cosmin. "Did you know: Nokia's Snake is not the world's first mobile game". Phone Arena. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ T, Nick. "This was the world's first cell phone with a game loaded on it". Phone Arena. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ Blog, Microsoft Devices (16 January 2013). "10 things you didn't know about mobile gaming". Microsoft Devices Blog. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ "N-Gage Launch - IGN". Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ Wortham, Jenna (5 December 2009). "Apple's Game Changer, Downloading Now (Published 2009)". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Apple Arcade: It's time to play". Apple Newsroom. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ https://www.4bilder-1wort.de/

- ↑ Baker, Chris (21 July 2016). "Why 'Pokemon Go' Sucks in the Suburbs". Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/why-pokemon-go-sucks-in-the-suburbs-103309/.

- ↑ Kushner, David (11 March 2014). "Exclusive: Flappy Bird Creator Speaks". Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/the-flight-of-the-birdman-flappy-bird-creator-dong-nguyen-speaks-out-112457/.

- ↑ "Rebel Inc. now available in Afghanistan" (in en). www.gamasutra.com. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/pressreleases/360457/Rebel_Inc_now_available_in_Afghanistan.php.

1990's

[edit | edit source]Origin of Standards

[edit | edit source]The first version of the programming language JavaScript is developed in just 10 days, eventually becoming the de facto locally run scripting language on the web.[1]

While not a true web standard, the first form of Flash is developed in 1996, enabling web animations through use of a plug in.[2] The high demand for such content quickly turns Flash into a de facto standard of sorts, though not an open one.

CSS level 1 is recommended by W3C on December 17, 1996.[3]

2000's

[edit | edit source]Rise of Web 2.0

[edit | edit source]The emergence of Web 2.0 and user generated content lead to the proliferation of game modding and machinima among gamers.[4]

Browser Monoculture under IE6

[edit | edit source]The end of the first browser war between Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigator ends with Netscape failing and web technologies stagnating hard for five years, and being stifled long afterwards.[5][6] After being in development since 1998, the first version of Firefox (Then the Phoenix Web Browser of the Mozilla Application Suite version 1.0) released in 2002, built from the open sourced remains of Netscape.[7][8] At the time Internet Explorer had over a 90% market share.[8]

The stagnation of web browsers lead to developers take advantage of browser plugins like Flash and Java to make their games, neither of which were ideal. Flash had poor 3D and networking support, and had serious performance issues.[9]

Peak Flash

[edit | edit source]During the 2000's Flash games enter their peak, with many becoming widely popular.[10] In 2005 Adobe purchases Macromedia, the company that owns Flash Player, for 3.4 billion dollars.[11]

When the iPhone launches, Steve Jobs refuses to allow Flash on Apple's mobile platforms, instead preferring more efficient and open technologies to handle tasks Flash is used for.[12][13]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]-

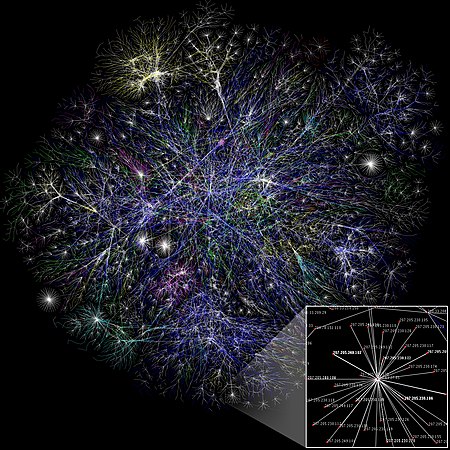

A partial map of the Internet in 2005. During this decade use of the Internet, and especially the World Wide Web, rapidly took off.

-

A Yahoo! Games booth at E3 2005.

-

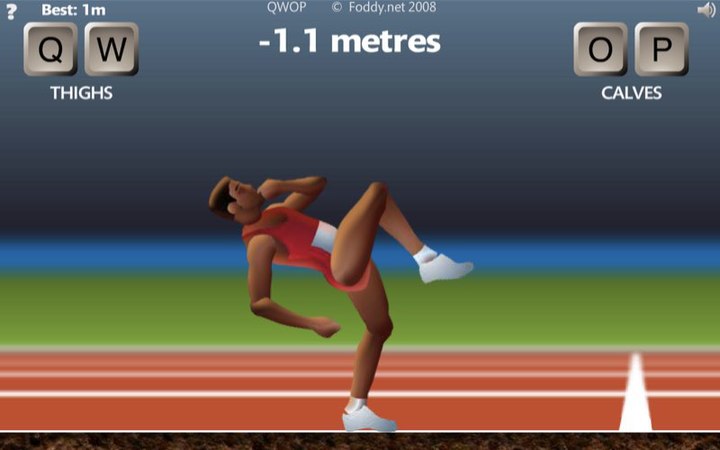

QWOP in 2008, an innovative browser game.

2010's

[edit | edit source]Web Standards Evolve

[edit | edit source]In 2014 HTML5 is finalized.[14]

Web Assembly entered widespread adoption in 2017, enabling faster web applications, including games running on web browsers.[15][16]

In 2016 Mozilla and the Google Chrome team collaboratively launched a WebVR API proposal to enable virtual reality support on the web.[17] WebVR was superseded by WebXR in 2018 to include augmented reality and mixed reality support for web browsers.[18][19]

Engines of Development

[edit | edit source]The engine Twine began commonly being used to bring interactive fiction to the web.[20][21]

Browser Monoculture under Chrome & Blink

[edit | edit source]By the late 2010's many sites began requiring the use of Google Chrome, leading to fears that browser technology may once again turn stagent[22]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]-

Socrates Jones: Pro Philosopher, an educational browser game from 2013.

-

A Facebook Gaming Booth at PAX west 2018.

2020's

[edit | edit source]End of Flash

[edit | edit source]Adobe has planned to end support for Flash Player on December 31st, 2020.[23] Also in 2020, the Internet Archive launches an in browser flash emulator to preserve old flash content.[24]

Other Developments

[edit | edit source]Notably on February 12th, 2021 Microsoft briefly promoted an unauthorized emulator for Mario Kart 64 on their Edge browser, before pulling the announcement.[25][26]

Notable Web Based Games

[edit | edit source]- Runescape

- Urban Dead

- Fallen London

- Agar.io

- Blaseball

Sony Station

[edit | edit source]An online game platform.[27]

Monopoly City Streets

[edit | edit source]A 2009 browser game featuring an early attempt to integrate geographical features from the real world into gameplay.[28]

Don't Look Back

[edit | edit source]A 2009 flash 2D shooter which is noted for integrating it's mechanics with the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, increasing the difficulty of the game considerably by ending the game should the player look back during the second half.[29]

LEGO.com Flash games

[edit | edit source]A notable and ever-changing collection of LEGO-themed Flash games, some of which have now been collected in an online archive.

Neopets

[edit | edit source]Though its general relevance declined, a small number of dedicated gamers kept playing two decades after its heyday.[30]

Mario Net Quest

[edit | edit source]A 1997 Shockwave Flash game made in collaboration between Nintendo, IBM, and C3 Entertainment.[31]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "CSDL IEEE Computer Society". www.computer.org. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Birth and Death of Flash". StreamShark. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ "20 Years of CSS". www.w3.org. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ↑ "Modding: Games and Web 2.0".

- ↑ Hutchinson, Lee (9 April 2014). "Looking at the Web with Internet Explorer 6, one last time". Ars Technica. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ Warren, Tom (4 May 2019). "Former Google engineer reveals the secret YouTube plot to kill Internet Explorer 6". The Verge. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ "Browser History: Epic power struggles that brought us modern browsers". Mozilla. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "History of the Mozilla Project". Mozilla. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ "Flash Limitations > First Steps of Flash Game Design Adobe Press". www.adobepress.com. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ Villa, Jesse (2 February 2019). "Gaming on the Web: The Rise and Fall of Browser Games". Medium. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ↑ Flynn, Laurie J. (19 April 2005). "Adobe Buys Macromedia for $3.4 Billion (Published 2005)". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ Pathak, Khamosh. "How to Use Adobe Flash on Your iPhone or iPad". How-To Geek. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ "Thoughts on Flash". web.archive.org. 22 July 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ "HTML5 finalized, finally". PCWorld. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ↑ Krill, Paul (6 March 2017). "WebAssembly is now ready for browsers to use". InfoWorld. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ↑ "WebAssembly for Native Games on the Web – Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog". Mozilla Hacks – the Web developer blog. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ↑ "Introducing the WebVR 1.0 API Proposal – Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog". Mozilla Hacks – the Web developer blog. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ "New API to Bring Augmented Reality to the Web – Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog". Mozilla Hacks – the Web developer blog. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ "Welcome to the immersive web". Google Developers. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ Robertson, Adi (10 March 2021). "Text Adventures: how Twine remade gaming". The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/22321816/twine-games-history-legacy-art.

- ↑ Ellison, Cara (10 April 2013). "Anna Anthropy and the Twine revolution". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/gamesblog/2013/apr/10/anna-anthropy-twine-revolution.

- ↑ Warren, Tom (4 January 2018). "Chrome is turning into the new Internet Explorer 6". The Verge.

- ↑ "Adobe Flash end of support on December 31, 2020 - Microsoft Lifecycle". docs.microsoft.com. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ "Flash Animations Live Forever at the Internet Archive".

- ↑ Peters, Jay (12 February 2021). "Microsoft’s Edge extensions store hosted illicit copies of Sonic and Mario Kart 64" (in en). The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/2/12/22281033/microsoft-edge-extensions-mario-kart-64-sonic-minecraft-games.

- ↑ "Microsoft's Edge Extensions Store Has Reportedly Been Hosting Illegal Copies Of Nintendo Games". Nintendo Life. 13 February 2021. https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2021/02/microsofts_edge_extensions_store_has_reportedly_been_hosting_illegal_copies_of_nintendo_games.

- ↑ "Sony Online Entertainment Announces A Diverse Lineup Of Games Available At Newly Revamped Station.Com". www.sony.com. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ↑ "'Monopoly City Streets' Online Game: Will Buying Park Place Be Any Easier?" (in en). PCWorld. 8 September 2009. https://www.pcworld.com/article/171610/Monopoly_Meets_Google_With_Monopoly_City_Streets.html.

- ↑ Short, Emily. "Analysis: Don't Look Back - Cavanagh's Alternate Game Viewpoints" (in en). gamasutra.com. https://gamasutra.com/view/news/115375/Analysis_Dont_Look_Back__Cavanaghs_Alternate_Game_Viewpoints.php.

- ↑ Morley, Madeleine (3 November 2021). "‘I Could Never Abandon Them’: Neopets Users Play On". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/11/03/arts/design/neopets.html.

- ↑ McFerran, Damien (24 April 2023). "Internet Sleuth Finds "Lost" Super Mario Browser Game From 1997". Time Extension. https://www.timeextension.com/news/2023/04/internet-sleuth-finds-lost-super-mario-browser-game-from-1997.

Introduction

[edit | edit source]Almost as long as there have been widely available programmable calculators, there have been games developed to run on them. What makes Calculator Gaming interesting from a historical standpoint is highly related to the hardware it runs on, and the institutional opposition to its very existence. Not only is calculator hardware not designed for games, compared to gaming hardware from the same time they are often nearly antithetical to running games. Manufacturers of calculators were often not friendly to gaming on calculators and took steps to prevent it.[1] Some calculator companies sought to protect their monopolistic place lucrative industry of academic technology,[2] and likely saw the ability of their devices to play games as a possible factor that could jeopardize their market position.

Yet calculator gaming persisted despite the odds. As programmable calculators became integrated with academic instruction, they quickly became a common item capable of playing games, yet few large commercial enterprises bothered trying to commercialize the platform. This means that nearly all Calculator games are homebrew, and thus are often fan games made with little concern for IP law, giving additional insight to the popular culture trends of the time. Often games were spread from calculator to calculator over communication cables, rather then from a central source.[3] Furthermore calculator hardware tended to be quite limited in comparison to gaming hardware, giving rise to a demoscene of sorts where skilled programmers would attempt to make games that most considered impossible on the hardware they ran on.

History

[edit | edit source]The HP-65 was introduced in 1974 as the first mass-produced programmable handheld calculator.[4] Notably, the HP-65 allowed Satoru Iwata to start programming games while in high school during the mid-1970's. This including his first game, a baseball simulator which was well received amongst his friends.[5][6] This lead him to an illustrious career as both a video game pioneer and a notable leader at Nintendo.[6]

A few deliberate attempts were made to blend calculators and gaming devices were made in the late 1970s to the early 1980's to varying results. The 1977 TI Dataman toy calculator attempted to use games as an educational tool for learning math.[7] In 1980 calculator technology was repurposed to make the first Game & Watch game consoles.[8] Though the Game & Watch were not calculators in and of themselves, they were said to be inspired by a rider on a Shinkansen train playing with a calculator.[8][9] Had it not been for calculator technology, one of the first handheld gaming consoles to see widespread popularity may have never been made.

Darth Vader's Force Battle was released in 1980 for the TI-59 calculator, becoming among the first documented games developed for calculator hardware which received widespread distribution.[10]

The 1985 introduction the Casio FX-7000G graphing calculator introduced graphing calculators monochrome dot matrix displays,[4] greatly increasing the kinds of games possible on calculators. However it was the 1990 introduction of the TI-81 with TI-Basic helped popularize calculator gaming by making it more accessible to beginner programmers,[11] which naturally worked well with the students who used the calculators who were themselves often beginner programmers. This transformed the calculator into a different sort of educational tool, and helped some self starting students learn computer programming.[11] The addition of a serial port and more capable hardware on the TI-85 in 1992 coupled with a trick developed in 1994 to allow non TI-Basic code to run on the system helped proliferate games coded in assembly language,[12] which could be more advanced by being more efficient with limited system resources.

The more powerful graphing calculators of the late 2000's and the introduction of color screens in the early 2010's ushered in a more standard calculator gaming experience, with more normal looking games and emulators written for these platforms.[12]

By 2014 unofficial ports of complex real time games such as Smash Bros were being made for older TI-84 hardware.[13]

By May 24th, 2020 Texas Instruments had announced that they would be removing support for assembly and C based programs on some of their calculators with a software update as a means to curb cheating,[1] a move which would also impact games using those languages. On May 27th, 2020 the computer enthusiast YouTube channel LinusTechTips demonstrated a significant, though slightly unstable, overclock (16 megahertz to 26.8 megahertz) of on a TI-84 by replacing a resistor with a potentiometer and adding a custom water cooling loop to run a port of Doom at a higher frame rate.[14]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Calculator Gaming

[edit | edit source]Calculator Hardware

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b "Texas Instruments makes it harder to run programs on its calculators" (in en). Engadget. https://www.engadget.com/ti-bans-assembly-programs-on-calculators-002335088.html.

- ↑ McFarland, Matt. "The unstoppable TI-84 Plus: How an outdated calculator still holds a monopoly on classrooms". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/innovations/wp/2014/09/02/the-unstoppable-ti-84-plus-how-an-outdated-calculator-still-holds-a-monopoly-on-classrooms/.

- ↑ "Ode to the Graphing Calculator" (in en-us). Lifehacker. https://lifehacker.com/ode-to-the-graphing-calculator-1795376992.

- ↑ a b "The History of Calculators: Evolution of the Calculator (Timeline)" (in en). EdTech Magazine. https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2012/11/calculating-firsts-visual-history-calculators.

- ↑ "Portrait : Il s'appelait Satoru Iwata : Hommage au visionnaire de Nintendo" (in fr). Jeuxvideo.com. https://www.jeuxvideo.com/news/1012034/portrait-il-s-appelait-satoru-iwata-hommage-au-visionnaire-de-nintendo.htm.

- ↑ a b "Happy Birthday, Satoru Iwata". Siliconera. 7 December 2020. https://www.siliconera.com/happy-birthday-satoru-iwata/.

- ↑ "Texas Instruments Dataman Handheld Electronic Calculator". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ a b "Iwata Asks". iwataasks.nintendo.com. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ Sherrill, Cameron (13 November 2020). "How a Glorified Calculator Shaped Nintendo for Generations". Esquire. https://www.esquire.com/lifestyle/a34659956/every-nintendo-game-and-watch-edition-photos/.

- ↑ "Byte Magazine Volume 05 Number 10 - Software". October 1980. https://archive.org/stream/byte-magazine-1980-10/1980_10_BYTE_05-10_Software#page/n51/mode/2up.

- ↑ a b Nichols, Phil (30 August 2013). "Go Ahead, Mess With Texas Instruments" (in en). The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/08/go-ahead-mess-with-texas-instruments/278899/.

- ↑ a b "The History of TI Graphing Calculator Gaming". Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ "Super Smash Bros On A Calculator". Hackaday. 18 November 2014. https://hackaday.com/2014/11/17/super-smash-bros-on-a-calculator/.

- ↑ "Water Cooling a TI-84 Graphing Calculator!". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l06PlYNShpQ.

Introduction to Fantasy Computers

[edit | edit source]Portability of software has long been an issue for programmers, and video game programmers are no exception. Over time, various technologies would live these concerns, but some of the technologies developed to aid portability would lead to a new class of gaming platform: the Fantasy Computer. Conceived entirely in software, rather than in hardware, these programs offered a standardized software environment with fixed capabilities, much like the typical low end home computers and consoles of the 1980's.

Notable Fantasy Computers

[edit | edit source]Proto Fantasy Computers: Chip-8 & SCUMM VM

[edit | edit source]Fantasy consoles have their roots in CHIP-8 in the 1970s. Similar environments designed specifically for interactive fiction would be seen with SCUMM and other software layers.

PICO-8

[edit | edit source]PICO-8 became perhaps the best known fantasy console in the 2010s. PICO-8 is noted for the forethought given to system limitations as a way of inspiring developmental creativity.[1][2] The system notably has its own "cartridge" format, which are actually images containing the game code through stenography.[3]

Among the most notable games for the PICO-8 is the original version of the award-winning 2D platformer Celeste, which was developed by Maddy Thorson and Noel Berry for a game jam.[4][5] This was followed by Celeste 2 for the PICO-8 on January 26th, 2021.[4][5]

TIC-80

[edit | edit source]TIC-80 is a Free and Open Source fantasy console that has similar restrictions to PICO-8. Its one of the most popular fantasy consoles due to its compatibility with a wide range of platforms and accessibility per gratis.[6] Just like PICO-8, TIC-80 supports extraction of programs as cartridges in png and other formats.[7]

LIKO-12

[edit | edit source]By September 18th, 2016 version 1.0.0 of the open source LIKO-12 was released.[8]

TEC Redshift Player

[edit | edit source]An interesting example of a fantasy console is the TEC Redshift Player. Released as freeware[9] by Zachtronics on September 25th, 2018, this companion console to the programming game Exapunks resembled a Game Boy with an additional button and red blue anaglyph stereoscopic support.[10] Uniquely the console included a fictitious history,[10] with parallels to real life Game Boy and Virtual Boy lines of consoles.[11] The system used the same fictional programming language as the rest of Exapunks.[12]

Supdrive

[edit | edit source]An NFT and blockchain oriented fantasy console announced on August 18th, 2021.[13][14][15] The console is spearheaded by Dom Hofmann, creator of the Vine video sharing platform.[14][15]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Reasons to use Pico-8 over other fantasy consoles?". www.lexaloffle.com. https://www.lexaloffle.com/bbs/?tid=39709.

- ↑ Pale, Patrick (10 November 2018). "Creativity Within Constraints: Having Fun with PICO-8". Atomic Spin. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ↑ "P8PNGFileFormat". PICO-8 Wiki. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ↑ a b Byford, Sam (26 January 2021). "The original Celeste now has a sequel you can play in your browser" (in en). The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/1/26/22249987/celeste-2-pico-8-sequel-available-now.

- ↑ a b Cryer, Hirun (January 26 2021). "Celeste Classic 2 is a challenging sequel to the PICO-8 original" (in en). gamesradar. https://www.gamesradar.com/celeste-anniversary-game/.

- ↑ Pistorio, Marco (September 2018). "Fantasy Console: TIC 80". Retro Magazine (in Italian). 2 (9): 20 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ https://kidscodecs.com/tic80-retro-games/

- ↑ "[LIKO-12 V1.0.0 An open-source fantasy computer made in LÖVE - LÖVE"]. love2d.org. https://love2d.org/forums/viewtopic.php?t=82913.

- ↑ "We can now all play Exapunks players' in-game games for free" (in en). Rock Paper Shotgun. 26 September 2018. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/exapunks-free-redshift-player-released.

- ↑ a b "EXAPUNKS: TEC Redshift Player on Steam". store.steampowered.com. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ↑ "Zachtronics's alternate 90s hacking sim Exapunks is out in early access" (in en). Rock Paper Shotgun. 9 August 2018. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/exapunks-hacking-early-access-launch#more-577863.

- ↑ "'Exapunks' Is a Cyberpunk Hacking Game That Asks You to Print Your Own Zines" (in en). www.vice.com. https://www.vice.com/en/article/mb44dn/exapunks-pc-steam-game-review.

- ↑ "https://twitter.com/dhof/status/1428093313412915203" (in en). Twitter. https://twitter.com/dhof/status/1428093313412915203.

- ↑ a b Clark, Mitchell (19 August 2021). "Vine’s creator is now working on NFT blockchain video games" (in en). The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/8/19/22632765/vine-creator-dom-hofmann-blockchain-video-game-nft-supdrive.

- ↑ a b "Vine's Founder Is Now Creating Blockchain-Backed Video Games". HYPEBEAST. 20 August 2021. https://hypebeast.com/2021/8/vine-founder-nft-blockchain-video-games-supdrive-dom-hofmann.

- Extended Reality Gaming

Early developments

[edit | edit source]While not the primary point of the story, a simulated reality is featured prominently in the Allegory of the Cave by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato[1][2][3] around 360 B.C.E.[4] While not VR as it is known today, the story not only shows the existence of simulated realities as a concept long before the invention of multimedia technology, it also shows an uncanny understanding of some of the same ethical questions people would ask about addiction to virtual worlds thousands of years later.[5][6] A similar concept also exists in Zhuangzi's ancient Daoist text the Butterfly Dream a third century B.C.E. story written in ancient China, though the method of simulation and lesson of the story are rather different.[7]

Simple stereoscopic displays have attempted to to offer immersive experiences since 1838 with the invention of the Stereoscope in Britain.[8][9] Rival Scottish physicist Sir David Brewster specialized in optics, having previously invented such things as the Kaleidoscope, and crafted a more refined and portable stereoscope.[10][11]

During the 1950's and 1960's a number of attempts were made to create more immersive experiences.[12]

Prototype Technology of the 1980's and 1990's

[edit | edit source]During the Cold War there was a massive amount of Research and Development ongoing by both government and commercial agencies, which had a side effect of trickling down to consumers later, namely in Virtual Reality, and general advances in computing. During this time, a number of marketing attempts to promote the technology would be made.[13] Though this technology would not see common consumer use in the 1980's and 1990's, it would form the basis for common gaming technologies decades later.

By 1992 there was a VR Golf center in New York City and a VR Mech Arcade in Chicago.[14]

Rebirth of Virtual Reality

[edit | edit source]The early 2010's saw a renewed interest in VR with crowdfunding platforms providing capital to spur development.[15][16] The mid 2010's saw large corporations begin to push into the field with their own entries in VR, AR, and MR.[17][18][19]

VR technology became a popular theme in science fiction around this time, and VR games were frequently used as a plot device in non-gaming media as a way of taking characters to another world with a more scientifically plausible technology. Popular fictional stories of the 2010's such as Ernest Cline's 2011 novel Ready Player One and Steven Spielberg's 2018 film of the same name[20] and Sword Art Online[21] prominently feature VR in their stories. Such fictional works in turn influenced VR content creators during this time, who strove to bring fiction to virtual reality.[22][23]

Around 2016 and 2017 media outlets began frequently expressing concern about the safety of VR.[24][25]

By 2021 around 1/5 of Facebook employees were doing work related to their VR platforms.[26][27]

High End VR

[edit | edit source]Oculus Rift

[edit | edit source]Low End VR

[edit | edit source]Interest in VR sparked interest in lowering the barrier of entry to VR experiences.

Read More

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Modern Spin on Plato's Cave Explores the Limits of 3D Reality" (in en). www.vice.com. https://www.vice.com/en/article/78e3xa/platos-cave-allegory-video-with-3d-quantum-mechanics.

- ↑ Kane, Pat. "Escape to the future with virtual reality". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2138305-escape-to-the-future-with-virtual-reality/.

- ↑ "The Promise and Disappointment of Virtual Reality". Literary Hub. 28 November 2017. https://lithub.com/the-promise-and-disappointment-of-virtual-reality/.

- ↑ "Queensborough Community College". www.qcc.cuny.edu. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ Johansson, Anna (17 April 2018). "9 ethical problems with VR we still have to solve" (in en-us). The Next Web. https://thenextweb.com/contributors/2018/04/18/9-ethical-problems-vr-still-solve/.

- ↑ "Allegory of the Cave Story" (in english). Destructoid. https://www.destructoid.com/stories/allegory-of-the-cave-story-193555.phtml.

- ↑ "Zhuangzi's Butterfly Dream Decentered". Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ "History of Virtual Reality". The Franklin Institute. 21 October 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ Thompson, Clive. "Stereographs Were the Original Virtual Reality". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Molecular Expressions: Science, Optics and You - Timeline - Sir David Brewster". micro.magnet.fsu.edu. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "180 years of 3D". Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "History of Virtual Reality". The Franklin Institute. 21 October 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ "The Wacky World of VR in the 80s and 90s". PCMAG. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ "Almost Reality -- A Look at Virtual Reality". www.gamezero.com. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall and Rise of Virtual Reality". The Verge. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Oculus responds to Kickstarter criticism with free headsets". the Guardian. 6 January 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Manjoo, Farhad (22 January 2015). "Microsoft HoloLens: A Sensational Vision of the PC's Future (Published 2015)". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Miller, Claire Cain (8 April 2014). "At Google, Bid to Put Its Glasses to Work (Published 2014)". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Facebook's $2 Billion Acquisition Of Oculus Closes, Now Official". TechCrunch. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Roettgers, Janko (29 March 2018). "How ‘Ready Player One’ Compares to Today’s VR Technology". Variety. https://variety.com/2018/digital/news/ready-player-one-vr-tech-1202739419/.

- ↑ "Manga Books - Best Sellers - Books - April 27, 2014 - The New York Times". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/books/best-sellers/2014/04/27/manga/.

- ↑ "Ernest Cline talks Ready Player One, Spielberg, and the future of VR" (in en). The Independent. 30 March 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/ready-player-one-ernest-cline-interview-steven-spielberg-virtual-reality-vr-a8277996.html.

- ↑ Lang, Ben (4 June 2017). "Taking After 'Sword Art Online', Oculus Founder Wants to Make a VR Game With Serious Consequences". Road to VR. https://www.roadtovr.com/oculus-founder-wants-to-make-vr-game-with-serious-consequences-permadeath-sword-art-online/.

- ↑ Stein, Scott. "The real dangers of virtual reality" (in en). CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/the-dangers-of-virtual-reality/.

- ↑ CNN, By Sandee LaMotte (13 December 2017). "The very real health dangers of virtual reality" (in en). CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2017/12/13/health/virtual-reality-vr-dangers-safety.

- ↑ "Facebook Now Has 10,000 People Working on VR and AR Devices". MUO. 12 March 2021. https://www.makeuseof.com/facebook-ar-vr-development/.

- ↑ Byford, Sam (12 March 2021). "Almost a fifth of Facebook employees are now working on VR and AR: report" (in en). The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/3/12/22326875/facebook-reality-labs-ar-vr-headcount-report.

Prototype Technology of the 1980's and 1990's

[edit | edit source]During the Cold War there was a massive amount of Research and Development ongoing by both government and commercial agencies, which had a side effect of trickling down to consumers later, namely in Augmented Reality, and general advances in computing. During this time, a number of marketing attempts to promote the technology would be made.[1] Though this technology would not see consumer use in the 1980's and 1990's, it would form the basis for common gaming technologies decades later.

HUD development greatly influenced AR development

-

Virtual-Fixtures in 1992, the first immersive augmented reality system.

-

Augmented reality in 1999, being used on a Helicopter.

Augmented Reality is fielded

[edit | edit source]The mid 2010's saw large corporations begin to push into the field with their own entries in Augmented Reality.[2][3] Google Glass and Microsoft Hololens help popularize the idea augmented reality devices in the public, though neither device sees widespread consumer use.[4]

-

A man using HoloLens.

-

Google Glass

-

Fiducial Markers, a common tool used by AR systems when markerless tracking is not possible due to technology constraints.

-

10,000 Moving Cities, a multiplayer Augmented Reality game.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "The Wacky World of VR in the 80s and 90s". PCMAG. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ Manjoo, Farhad (22 January 2015). "Microsoft HoloLens: A Sensational Vision of the PC's Future (Published 2015)". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Miller, Claire Cain (8 April 2014). "At Google, Bid to Put Its Glasses to Work (Published 2014)". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Google Glass, HoloLens, and the Real Future of Augmented Reality" (in en). IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. https://spectrum.ieee.org/consumer-electronics/audiovideo/google-glass-hololens-and-the-real-future-of-augmented-reality.

Foundations

[edit | edit source]As augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality applications proliferated it became clear that an umbrella term was needed for these related spacial interactive technologies. Though XR (eXtended Reality) began entering popular use among game developers as a catch all term for applications falling anywhere on this reality to virtuality continuum.

Developments

[edit | edit source]In 2019 Audi experimented with XR technology as both in car entertainment and as a motion sickness treatment.[1]

References

[edit | edit source]