Chapter 6 Early modern period part 2

The early modern period was circa 1500–1750 AD, or ending at the French Revolution (1789), or at 1800. This second chapter on the early modern period discusses the Age of Discovery and colonial empires, Reformation and religious turmoil (including the Thirty Years' War), religious tensions in England and Scotland, and aspects of modernity.

Age of Discovery and colonial empires

[edit | edit source]

Age of Discovery was from circa 1400 to 1800. Lands include the Americas (the New World); southern Africa; Congo River; West Indies; India; Maluku Islands (Spice Islands); Australasia; New Zealand; Antarctica; and Hawaii. Largely coincided with the Age of Sail (1571–1862).

Spanish and Portuguese empires

[edit | edit source]Spanish Empire (1492–1975) began when Christopher Columbus landed in the New World in 1492. This was followed by La Conquista, the Spanish colonization of the Americas by the conquistadores. Cortes conquered the Aztecs after the Spanish–Aztec War (1519–21). In 1532 Pizarro conquered the Inca empire in Peru. The Maya and many other peoples were also conquered. Ferdinand Magellan was a Portuguese explorer that organised the Spanish expedition that achieved the first global circumnavigation, 1519–1522, which was completed after his death by Juan Sebastián Elcano.

The Spanish Empire would be mostly divided into viceroyalties:

- Viceroyalty of the Indies (1492–1526)

- Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821)

- Viceroyalty of Peru (1542–1824)

- Viceroyalty of New Granada (1717–1819)

- Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (1776–1814)

The Viceroyalty of New Spain would include the Spanish East Indies (the Philippine Islands, the Mariana Islands, the Caroline Islands, parts of Taiwan, and parts of the Moluccas), and the Spanish West Indies (Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, Trinidad, and the Bay Islands). It also included a substantial portion of mainland Americas, including Spanish Louisiana.

The Portuguese Empire began in 1415. The Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, during his voyage to India (1497–1499), performed the first navigation around South Africa, to connect the Atlantic and the Indian oceans. This would contribute to Portuguese dominance in trade routes around Africa, particularly in the spice trade for around a century.

The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) split the world between regions of Spanish and Portuguese influence, but this was ignored by other nations. This resulted in the Spanish being particularly active in Americas, while Portuguese influence in the Americas was limited to Brazil. The Portuguese established a large number of trading posts around the coasts of India, the East Indies, Africa and Arabia.

During the Iberian Union (1580-1640) the empires of Portugal and Spain were combined. With the Dutch–Portuguese War (1601–1663), Dutch attempts to secure Brazil and Angola from Portugal failed; the Dutch were the victors in the Cape of Good Hope and the East Indies, capturing Malacca, Ceylon, the Malabar Coast, and the Moluccas from the Portuguese, but not Macau.

Other empires

[edit | edit source]Major European colonial empires that followed the Spanish and Portuguese included:

- English Empire, from 1583, which in 1707 became British.

- French Empire, 1534–1980.

- Dutch Empire, from 1581.

Other European colonial empires included the Danish overseas colonies and Swedish overseas colonies, and Russia greatly expanded in the early modern period. Non-European empires included the Great Qing Empire of China (1636–1912); the Ashanti Empire (1701–1896, a West African state of the Ashanti); and the Sikh Empire (1799–1846) and Maratha Empire (1674–1818) in India; and the Turkish Ottoman Empire around the Mediterranean and Black Sea. The Omani Empire (1696–1856) was a maritime empire in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean.

Dutch colonies were split between the Dutch East India Company (particularly in the East Indies and South Africa) and Dutch West India Company (mainly on the east coast of the Americas). The Dutch discovered Australia in 1606, and New Zealand in 1642; both of these would later colonised by the British. Anglo-Dutch Wars: were a series of four wars fought in the 17th and 18th centuries; largely a result of English and Dutch rivalry, mainly over trade and overseas colonies; most battles were fought at sea.

In North America, the British, French and Spanish dominated. South and Central America was mainly Spanish, with the Portuguese in Brazil. The Danish empire (1536–1953) included Norway, Iceland and Greenland. The Swedish empire (1638–1663 and 1784–1878) mainly consisted of Finland and the Baltic states.

In the late modern period (19th and early 20th centuries), Italy, Germany, Belgium, Japan and the USA established empires. The British Empire rapidly expanded in this period, and eventually included India, Australia and much of Africa. France colonized much of North Africa, and French Indochina (today Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia).

Slavery and piracy

[edit | edit source]Atlantic slave trade was a major source of wealth to Europe and its colonies; beginning with the Portuguese in 1526, it reached a zenith between 1780 and 1800.

In many cases it was a triangular trade; manufactured goods from Europe would be exchanged on the western coats of Africa for slaves; these slaves would be exported to North and South America, and the West Indies; and raw goods would be exported back to Europe. By volume, the empires trading slaves were the Portuguese, British, French, Spanish, and Dutch Empires. It is estimated that over 12 million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic, until it started being outlawed, firstly by Denmark in 1803, and then Britain in 1807. In 1888 Brazil became the last Western country to abolish slavery.

Golden Age of Piracy: spans the 1650s to the late 1720s. Main seas of piracy were the Caribbean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea. It includes colorful pirates of the Caribbean such as Henry Morgan, William 'Captain' Kidd, 'Calico' Jack Rackham, Bartholomew Roberts and Blackbeard (Edward Teach).

Reformation and religious turmoil

[edit | edit source]

Proto-Protestantism and earlier movements

[edit | edit source]

The Roman Catholic religion has been challenged throughout its history. For example, in the High Middle Ages the Cathars of southern France had broken with Catholic doctrine; this led to the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) and genocide of the Cathars.

Proto-Protestantism were movements that challenged Catholicism, and influenced the Protestant Reformation; these included:

- Hussites

- A Christian movement of the pre-Protestant Bohemian Reformation. They followed Jan Hus, who was burnt at the stake in 1415. The Hussite Wars (1419–1434), resulted in victory for the Moderate Hussites, but defeat for the Radical Hussites; the Hussite religion was thus established in Bohemia for two centuries. After the Bohemian Revolt (1618–1620), the first phase of the Thirty Years' War, they were suppressed.

- Waldensians

- Founded in the 1170s by Peter Waldo, they would come to influence Anabaptism in particular.

- Lollards

- Founded by John Wycliffe, a 14th century English theologian, they played a part in the English Reformation.

Protestant Reformation

[edit | edit source]The Protestant Reformation was the establishment of Protestantism in a 16th-century western Europe, whose religion was dominated by the Roman Catholic Church.

The Protestant Reformation began in 1517, at Wittenberg, Saxony, when Martin Luther sent his Ninety-Five Theses to the Archbishop of Mainz; these protested against the sale of plenary (meaning unqualified) indulgences, which were sold by the clergy, and thought to remit the soul from punishment by God. Following the Diet of Worms of 1521 (an assembly of the Holy Roman Empire in the Imperial Free City of Worms), Luther was excommunication by Pope Leo X, and condemned as an outlaw by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

Early Protestant movements included:

- Lutheranism

- Was based on the teachings of Martin Luther; Lutheran churches became dominant especially in the north of Germany and in the Scandinavian countries.

- Calvinism, or the Reformed tradition

- Was based on teachings which included those of Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin. Calvinism spread to the Dutch Republic, Scotland (Presbyterians), and southern France (Huguenots), and to a lesser extent Germany, Hungary, and England (Puritans).

- Anglicanism

- Was created by Henry VIII, and became the dominant religion of England as the Church of England; it incorporated aspects from the Reformed and Lutheran churches. The Anglican Communion would spread to become the third largest Christian communion (after Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy).

- Anabaptism

- Was an early offshoot of Protestantism, and Anabaptist churches would include the Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites fellowships.

- Unitarianism

- Is an nontrinitarian theological movement, and Unitarian churches began in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Transylvania.

The Peace of Augsburg (1555) of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and the Schmalkaldic League (of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire) allowed rulers within the Holy Roman Empire to choose either Lutheranism or Roman Catholicism as the official confession. Calvinism was not allowed in the Holy Roman Empire until the Peace of Westphalia (1648).

Counter-Reformation

[edit | edit source]

Counter-Reformation: was a period of Catholic resurgence in response to the Reformation. It began with the 25 sessions of the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which led to reform of Church doctrines and teachings; the next ecumenical council was the First Vatican Council (1869).

There was also the formation of seminaries for the training of priests; the Jesuits, a new religious order, began missionary work, as well as the Augustinians, Franciscans, and Dominicans.

The Inquisition. which had started in 12th-century France, was used to enforce the Counter-Reformation and suppress heresy; it included the Spanish Inquisition, the Roman Inquisition, and the Portuguese Inquisition.

European wars of religion

[edit | edit source]European wars of religion of the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries, were largely a result of the religious differences stemming from reform. They included the Thirty Years' War (see below),

The French Wars of Religion (1562–1598) were especially notable, with Roman Catholics against the Huguenots (French Protestants) following the death of Henry II of France; three millions deaths can be attributed to them. The Bartholomew's Day massacre (1572) was the massacre of between 30,000 and 100,000 Huguenots across France. Henry IV, a former Huguenot, issued the Edict of Nantes (1598) assuring conditional religious freedom. Later on, Huguenot rebellions (1621–1629) erupted after intolerance by Louis XIII. Louis XIV's Edict of Fontainebleau (1685) revoked the Edict of Nantes, and resulted in further persecution.

Other major European wars of religion include:

- War of the Three Kingdoms (1639–1651) of England, Scotland, and Ireland;

- Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) resulting in independence of the Dutch Republic from Spain;

- German Peasants' War (1524–1525) of the Holy Roman Empire.

There was also a rise in witch trials between 1580 and 1630; over 50,000 people, mostly women, lost their lives, and religious tensions may have been a factor.

Thirty Years' War

[edit | edit source]

The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) was an especially devastating European war of religion. It was fought roughly between two factions (although some allegiances would change during it). These included:

- The Catholic Habsburg states and allies, which included the Habsburg Austrian Monarchy and Habsburg Spain, and the Catholic League (mainly southern states of the Holy Roman Empire). The Holy Roman Emperors Ferdinand II and Ferdinand III, who reigned 1619–1637 and 1637–1657, spearheaded the Catholics; the Count of Tilly, and Albrecht von Wallenstein, were successful generals for the Catholic forces.

- The anti-Habsburg states were mainly Protestant, with the notable exception of Catholic France. It also included the Scandinavian states of Denmark–Norway and Sweden; the Dutch Republic; and England and Scotland. It included some Holy Roman Empire states (like Bohemia, Electoral Palatinate, Saxony, and Brandenburg-Prussia), although some would join the fight against France. France was ruled by Louis XIII (1610–1643) and Louis XIV (1643–1715), and Cardinal Richelieu was First Minister of State (1624–1642).

There were many aspects to the war, but important ones include:

- Bohemian Revolt (1618–1620)

- A revolt of the mainly Hussite population of Bohemia (see Proto-Protestant movements above) against the Catholic rule of the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Ferdnand II, who became King of Bohemia (1617–1619 and 1620 –1637). The 1618 Defenestration of Prague was when two Catholic nobleman and their secretary, who represented Ferdinand II, were thrown out of a window of Prague Castle by protesting Hussites; all three survived the fall. It ended in success for Ferdinand II, with the decisive Battle of White Mountain (1620), and many Bohemian nobles were executed.

- Palatinate campaign (1620–1623)

- Frederick V of the Palatinate was a Calvinist, and had attempted to usurp Ferdinand II's rule of Bohemia, temporarily becoming King of Bohemia (1619–1620). An Austrian and Spanish Habsburg army invaded Electoral Palatinate to oust Frederick V; the conquest was successful, but the campaign widened the conflict.

- Danish involvement (1625–1629)

- Christian IV of Denmark, King of Denmark–Norway, was a Lutheran, and invaded the Holy Roman Empire to support the Protestants; but he was soon forced to retreat. With the Treaty of Lübeck (1929), Denmark–Norway participation ended, and their nation would then decline.

- Swedish involvement (1630–1648)

- Protestant Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden invaded the Holy Roman Empire with considerable success, with battles such as the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631). During this time, the Sack of Magdeburg (1631) was the destruction of the Protestant city of Magdeburg by Catholic forces. Adolphus was killed at the Battle of Lützen (1632), and succeeded by Christina, Queen of Sweden. After a crushing defeat at the Battle of Nördlingen (1634), Swedish military involvement ended for two years.

- French involvement (1635–1648)

- Bourbon France, whose allies included Sweden and the Dutch Republic, fought against Habsburg Spain, allied with Habsburg Austria and the Holy Roman Empire; this began the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659), and was despite the Bourbons and Habsburgs being Catholic. The Peace of Prague (1635) more or less ended Holy Roman Empire civil war aspects. The French had a great general in the Viscount of Turenne. It included the Battle of Rocroi (1643), a decisive French victory over the Spanish. There were important Swedish victories against the Holy Roman Empire at the Battle of Wittstock (1636) and Battle of Jankau (1645).

Other aspects of the Thirty Years' War, and parallel conflicts, included:

- Involvement of Calvinist Transylvania (under Gabriel Bethlen), supported by the Ottomans, from 1619.

- From 1619 the Dutch Republic became involved, despite the Twelve Years' Truce (1609–1621) between the Dutch Republic and Spain.

- Protestant Huguenot rebellions in France, sporadically between 1621 and 1629, which were unsuccessful.

- The Peasants' War in Upper Austria (1626), the unsuccessful attempt to free Upper Austria from Bavarian rule.

- The War of the Mantuan Succession in northern Italy (1628–1631), a success for the French against the Habsburgs.

- From 1940, the Reapers' War (or Catalan Revolt), and Portuguese Restoration War (see below).

Peace of Westphalia (1648) ended the Thirty Years' War. There were agreements between the Holy Roman Empire and France and Sweden, and between the Dutch and Spanish. But the Franco-Spanish War continued (see below).

- There were a roughly eight million fatalities, including soldiers (700,000–1,800,000, mostly from disease) and civilians (3,500,000–6,500,000, mostly from disease and starvation). There was widespread famine and devastation of the Holy Roman Empire as a result of the war.

- The war weakened the Holy Roman Emperor and the Habsburgs, with power returned to the Imperial Estates.

- There was formal independence for the Dutch Republic with the end of the Eighty Years' War (the Dutch War of Independence, 1568–1648); and also for Switzerland.

- Territorial changes included gains by France, Sweden, and Brandenburg-Prussia.

- Princes within the Holy Roman Empire could determine their state's religion from Catholicism and Lutheranism, and now Calvinism was also acceptable.

Franco-Spanish War and Portuguese Restoration War

[edit | edit source]After 1648, the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659) continued in Italy, the Low Countries, and Catalonia; the Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668) in Portugal and Spain also continued. The Anglo-Spanish War (1654–1660) was related to the Franco-Spanish War.

- The Reapers' War (1640–1659), or the Catalan Revolt, was a part of the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659). It included the French occupation of Roussillon in the Eastern Pyrenees (1642). The Franco-Spanish War concluded with the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), and the Spanish ceded Northern Catalonia and other border territories to France; France also gained French Flanders.

- The Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668) resulted in the breaking up of the Iberian Union of Spain and Portugal, with England and France helping Portugal defeat Spain. With the Treaty of Lisbon (1668), Spain lost Portugal.

Conflict between France and Habsburg Spain would continue with later wars, the War of Devolution (1667–68), the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678), the War of the Reunions (1683–1684), and the Nine Years' War (1688–1697).

Religious tensions in England and Scotland

[edit | edit source]

Henry VIII of England (who reigned 1509–1547) was the second Tudor king after his father Henry VII. He oversaw the English Reformation, with the establishment of the Anglican faith and Church of England, and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. He also began the Tudor conquest of Ireland (1529–1603), which expanded English rule to all of Ireland; he also oversaw the legal union of England and Wales. Henry VIII was succeeded by three of his children:

- Edward VI (who reigned 1547–1553), a Protestant Tudor king like his father; he died at the age of 15.

- Mary I (who reigned 1553–1558), a Catholic Tudor queen. She was married to Philip II of Spain, and she attempted to reverse the English Reformation. Her persecution of Protestants gave her the nickname Bloody Mary.

- Elizabeth I (who reigned 1558–1603), a Protestant and the last Tudor monarch. Her reign included the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588), an attempted invasion by Philip II of Spain, who was a staunch Catholic. Unmarried, she was succeeded by James I of England.

The Scottish Reformation resulted in the establishment of Church of Scotland (or the Kirk), which is Presbyterian and predominantly Calvinist; John Knox was one of the leaders. The Catholic rule of Mary, Queen of Scots was followed by her son James VI of Scotland (1567–1625), a Protestant Stuart.

James VI of Scotland would become James I of England (1603–1625), the first Stuart monarch of England, and subsequent monarchs would rule Scotland, England, Wales, and Ireland. He survived an early attempted assassination by Catholics with the Gunpowder Plot (1605). James I was succeeded by his son Charles I.

Wars of the Three Kingdoms, Commonwealth, and Restoration

[edit | edit source]Charles I (who reigned 1625–1649) was a Protestant Stuart king. But he married a Catholic and had Catholic sympathies, which caused Parliamentary concerns, as did his outspoken belief in the "Divine Right of Kings". The Eleven Years' Tyranny (1629–1640) was when Charles I ruled under the Royal Prerogative, without recourse to Parliament. Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, and the Eleven Years' Tyranny was a peak time for them leaving for New England.

Charles I's reign resulted in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639–1651), and his execution in 1649. The "Three Kingdoms" were England (and Wales), Ireland, and Scotland, and the wars were partly religious in origin; they included the English Civil Wars (1642–1651). Parliamentarians ("Roundheads") would defeat the Royalists ("Cavaliers"). Thomas Fairfax was the Parliamentary commander-in-chief, replacing the Earl of Essex Robert Devereux; he led Parliament to many victories, including the crucial Battle of Naseby (1645), but he would be politically out-maneuvered by his subordinate Oliver Cromwell.

England then entered the Commonwealth of England (1649–1660), with Oliver Cromwell becoming Lord Protector (1653–1658). During the Commonwealth, Scotland lost some of its independence, which was reversed during the Restoration in Scotland (1660). Cromwell was a Puritan, and Puritans became especially significant during the Protectorate (1653–1659, the period with a Lord Protector). The ineffectual rule of Richard Cromwell, Oliver's son and Lord Protector (1658–1659), would eventually lead to the downfall of the Commonwealth.

The Restoration was the return of the monarchy, with Charles II (who reigned 1660–1685), a Protestant Stuart king with Catholic sympathies, and the son of Charles I. Anti-Catholic hysteria resulted in the Popish Plot (1678–81), an invented Catholic conspiracy to dethrone Charles II, perpetrated by Titus Oates; nine Jesuits were executed and twelve died in prison, and other Catholic religious orders were repressed. Charles dissolved the Parliament in 1681, ruling as a absolute monarch until his death. Having only had illegitimate children, Charles II was succeeded by his brother James II of England.

Glorious Revolution, and the last Stuarts

[edit | edit source]James II of England (VII of Scotland), who reigned 1685–1688, was the Stuart brother of Charles II. His reign ended with the Glorious Revolution (1688), his ousting by Parliament and the army of William of Orange, mainly over his Catholic religion.

After the Glorious Revolution, all further monarchs were Protestant. James II was succeeded by his Stuart daughters:

- Mary II (who reigned 1689–1694), who had married to William of Orange (who reigned 1689–1702), who was William III of England and II of Scotland, and Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic.

- Anne of Great Britain (who reigned 1702–1714) was the last Stuart monarch. During her reign the Acts of Union (1707) united the government of Scotland with England (and Wales), as the Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1801); the Parliament of England became the Parliament of Great Britain; in 1801 it became the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

The Stuart dynasty (monarchs of Great Britain and Ireland 1603–1649 and 1660–1714) was succeeded by:

- House of Hanover (1714–1901), which included the Georgian (1714–1830 or 1837) and Victorian (1837–1901) eras.

- House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1901–1917), which was renamed the House of Windsor (1917–present day).

Williamite War and Jacobite risings

[edit | edit source]During the Williamite War in Ireland (1689–1691), which took place in Ireland, James II was defeated by William of Orange. James left Ireland after a reverse at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690.

The Jacobite risings were failed Catholic uprisings that sought to instate James II and his descendants; they are named after Jacobus, which is Latin for James. Since 1603 Scotland had shared the same monarch as England (and Wales and Ireland). They took place mainly in Scotland, with the backing of Catholic Scottish Highlander clansmen.

The most important risings were:

- Jacobite rising of 1689 (first rising) was a failed attempt to reinstate James II. It was followed by the Massacre of Glencoe (1692), the massacre of about 30 unarmed members of Clan MacDonald of Glencoe, allegedly for failing to pledge allegiance to William III and Mary II.

- Jacobite rising of 1715 (the '15) was a failed attempt to instate James Edward Stuart ("the Old Pretender"), the son of James II. England was then ruled by the Hanoverian King George I.

- Jacobite Rising of 1719 (the '19) was a smaller uprising of James Edward Stuart with the support of Spain.

- Jacobite rising of 1745 (the '45) was a failed attempt to instate Charles Edward Stuart ("the Young Pretender" or "Bonnie Prince Charlie"), the son of James Edward Stuart. The Battle of Culloden (1746) ended the rising with a decisive government victory, whose army was commanded by the Duke of Cumberland; the English king at the time was the Hanoverian George II.

Rise of philosophy, the arts, science and trade

[edit | edit source]

The Renaissance

[edit | edit source]The Renaissance (circa 1300 to circa 1600) began with the Italian Renaissance. Borrowed from French word "renaissance", it literally meant "rebirth", as it was seen as a rebirth of Classical learning and culture. There were developments in philosophy (particularly humanism), science, technology, and warfare. There were also artistic developments, including architecture, dance, fine arts, literature and music. There was renewed interest in Classical Roman and Greek texts, but also translations of Arabic texts. The invention of the printing press, which was greatly improved by the German Johannes Gutenberg circa 1439, helped in the dissemination of learning.

Proto-Renaissance in Italy (circa 1280-1400) writers included Dante Alighieri, who wrote the Divine Comedy (c. 1308 to 1320). Petrarch (1304–1374) was an early proponent of humanism. Giotto was an early artist. Early Renaissance in Italy (circa 1400-1495) artists included the sculptor Donatello; and the painters Masaccio, Sandro Botticelli, Giovanni Bellini, Filippo Lippi, and Paolo Uccello. Filippo Brunelleschi was one of the foremost architects and engineers.

The High Renaissance in Italy (circa 1495–1520) included Leonardo da Vinci, early Michelangelo, Raphael, and the architect Bramante, It also included Antonio da Correggio. It ended with the death of Raphael. Later painters included Titian, Tintoretto, and Paolo Veronese.

The House of Medici ruled Florence (as the Republic then Duchy of Florence, and as the Grand Duchy of Tuscany), for most of the period from 1434 to the early 18th century. They patronized many intellectuals associated with the Renaissance; these included Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Niccolò Machiavelli, Galileo Galilei and Sandro Botticelli. Lorenzo de’ Medici is particularly associated with this patronage.

The Roman Inquisition began in 1542, and suppressed some aspects of the Renaissance. It made some books forbidden, such as On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Sphere by Polish scientist Nicolaus Copernicus; first printed in 1543, it promoted the heliocentric theory of the Solar System. It also held trials against intellectuals; Galileo Galilei, who supported the work of Copernicus in his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), was put on trial.

Outside of Italy, Renaissance ideas soon spread across Europe to countries such as England, France, Germany, Hungary, the Low Countries, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Croatia, and Scotland. In the English Renaissance, the works of William Shakespeare (1564–1616) are often regarded as the greatest in English literature. Other notable artists included: the German artists Hans Holbein the Younger, Hans Holbein the Elder, and Albrecht Dürer; the Dutch artists Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, and Jan van Eyck; and the Greek artist El Greco.

Baroque Period and Age of Enlightenment

[edit | edit source]Baroque Period (17th and 18th centuries) was characterised by highly ornate styles in architecture, music, painting, and sculpture. Artists included Velázquez, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Rubens, Poussin, and Vermeer. Baroque composers included Johann Sebastian Bach, Antonio Vivaldi, George Frideric Handel, Claudio Monteverdi, and Henry Purcell. It was followed by the Classical period of music; roughly between 1730 and 1820, it included Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Franz Schubert. Rococo, or "Late Baroque", spread across Europe in the mid-18th century.

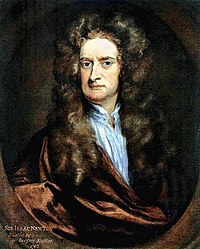

Age of Enlightenment or Age of Reason, was during the 17th and 18th centuries. Ideas that were developed were characterised by being secular, pluralistic, rule-of-law-based, with an emphasis on individual rights and freedoms. There was also an emphasis on science. Prominent scientists included Isaac Newton (1642–1727) and Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716), who built on the earlier work of Francis Bacon (1561–1626), the father of empiricism. Prominent philosophers included:

- French philosophers René Descartes (who contributed to rationalism), Voltaire (a particular advocate of freedom of speech and religion), Denis Diderot (and his Encyclopédie), and Montesquieu (and his theory of separation of powers).

- English philosophers John Locke and Thomas Hobbes, who both contributed to empiricism and social contract theory.

- Prussian-German philosopher Immanuel Kant, and the doctrine of transcendental idealism.

- Dutch-Portuguese philosopher Baruch Spinoza, a rationalist.

Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin greatly influenced the French Revolution and the American Revolution. The encyclopedia Encyclopédie (1751–72), edited by Denis Diderot, was a great success of the period.

Enlightened absolutism, the use of the Enlightenment to espouse absolute monarchy, was a curious side effect; much later it was followed by the concept of the benevolent dictatorship. Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor 1765–1790, was a prominent monarch of the Enlightenment and enlightened absolutism, along with Catherine the Great of Russia, and Frederick the Great of Prussia.

Capitalism and mercantilism

[edit | edit source]Rise of capitalism: capitalism became a dominant force in the sixteenth century, with the abolition of feudalism. It took its name from capital, defined by Adam Smith as "that part of man's stock which he expects to afford him revenue". The investment of capital became the primary factor in the accumulation of wealth.

Mercantilism, the exporting goods from countries, also rose in importance, particularly as a result of colonialism, with the trade of slaves and goods across the Atlantic Ocean being particularly important.