Intellectual Property and the Internet/Search engines

A search engine is a software system that is designed to search for information placed on web pages on the Internet. The response from the service is generally presented in a vertical list on what is most often referred to as a results page. The information may be a mix of web pages, images, videos, maps and other types of files. Some search engines also mine data from public databases or open directories. Unlike web directories, which are maintained only by human editors, search engines also maintain real-time information by running a web crawler which applies their search algorithm to all new and changed web pages it finds. Internet content that is not capable of being searched by a web search engine is generally described as the "deep web."

History

[edit | edit source]| Year | Engine | Current status |

|---|---|---|

| 1993 | W3Catalog | Inactive |

| Aliweb | Inactive | |

| JumpStation | Inactive | |

| World-Wide Web Worm | Inactive | |

| 1994 | WebCrawler | Active (Aggregator) |

| Go.com | Inactive (redirects to Disney) | |

| Lycos | Active | |

| Infoseek | Inactive (redirects to Disney) | |

| 1995 | Daum | Active |

| Magellan | Inactive | |

| Excite | Active | |

| SAPO | Active | |

| Yahoo! (directory) | Active (as Yahoo! Search since 2004) | |

| AltaVista | Inactive (acquired by Yahoo!: 2003, redirected: 2013) | |

| 1996 | Dogpile | Active (Aggregator) |

| Inktomi | Inactive (acquired by Yahoo!) | |

| HotBot | Active (Lycos.com) | |

| Ask Jeeves | Active (rebranded as Ask.com) | |

| 1997 | Northern Light | Inactive |

| Yandex | Active | |

| 1998 | Active | |

| Ixquick | Active (alias of Startpage) | |

| MSN Search | Active (as Bing) | |

| empas | Inactive (merged with NATE) | |

| 1999 | AlltheWeb | Inactive (redirects to Yahoo!) |

| GenieKnows | Active (rebranded Yellowee.com) | |

| Naver | Active | |

| Teoma | Inactive (redirects to Ask.com) | |

| Vivisimo | Inactive | |

| 2000 | Baidu | Active |

| Exalead | Active | |

| Gigablast | Active | |

| 2001 | Kartoo | Inactive |

| 2003 | Info.com | Active |

| Scroogle | Inactive | |

| 2004 | Yahoo! Search | Active (originally Yahoo! (directory), 1995) |

| A9.com | Inactive | |

| Sogou | Active | |

| 2005 | AOL Search | Active |

| SearchMe | Inactive | |

| 2006 | Soso | Inactive (redirects to Sogou) |

| Quaero | Inactive | |

| Search.com | Active | |

| ChaCha | Inactive | |

| Ask.com | Active (originally Ask Jeeves, 1996) | |

| Live Search | Active (as Bing, originally MSN Search, 1998) | |

| 2007 | wikiseek | Inactive |

| Sproose | Inactive | |

| Wikia Search | Inactive | |

| Blackle.com | Active (alias of Google) | |

| 2008 | Powerset | Inactive (redirects to Bing) |

| Picollator | Inactive | |

| Viewzi | Inactive | |

| Boogami | Inactive | |

| LeapFish | Inactive | |

| Forestle | Inactive (redirects to Ecosia) | |

| DuckDuckGo | Active | |

| 2009 | Bing | Active (originally MSN Search, 1998) |

| Yebol | Inactive | |

| Mugurdy | Inactive | |

| Scout (by Goby) | Active | |

| NATE | Active | |

| Ecosia | Active | |

| 2010 | Blekko | Inactive (sold to IBM) |

| Cuil | Inactive | |

| Yandex (English) | Active | |

| 2011 | YaCy | Active (Peer-to-peer search engine) |

| 2012 | Volunia | Inactive |

| 2013 | Qwant | Active |

| Infoseek | Inactive (redirects to Disney) | |

| 2014 | Egerin | Active (Kurdish/Sorani search engine) |

| 2015 | Cliqz | Active (browser-integrated search engine) |

| 2016 | Search Encrypt | Active |

Internet search engines themselves predate the debut of the Web in December 1990. The Who is user search dates back to 1982[1] and the Knowbot Information Service multi-network user search was first implemented in 1989.[2] The first well-documented search engine that searched content files, namely FTP files was Archie, which debuted on September 10th, 1990.[3]

Prior to September, 1993, the World Wide Web was entirely indexed by hand. There was a list of web servers edited by Tim Berners-Lee and hosted on the CERN web site. One Google.nl snapshot of the list in 1992 remains,[4] but as more and more web servers went online, the central list could no longer keep up. On the NCSA (National Center for Supercomputing Applications) site, new servers were announced under the title "What's New!"[5]

The first tool used for searching content (as opposed to users) on the Internet was Archie.[6] The name stands for "archive," without the "v". It was created by Alan Emtage, Bill Heelan and J. Peter Deutsch, all computer science students at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The program downloaded the directory listings of all the files located on public, anonymous FTP (File Transfer Protocol) sites to create a searchable database of file names; however, Archie Search Engine did not index the contents of these sites, since the amount of data was so limited it could be readily searched manually.

The rise of Gopher (created in 1991 by Mark McCahill at the University of Minnesota) led to two new search programs, Veronica and Jughead. Like Archie, they searched the file names and titles stored in Gopher index systems. Veronica (Very Easy Rodent-Oriented Net-wide Index to Computerized Archives) provided a keyword search of most Gopher menu titles in the entire Gopher listings. Jughead (Jonzy's Universal Gopher Hierarchy Excavation And Display) was a tool for obtaining menu information from specific Gopher servers. While the name of the search engine "Archie Search Engine" was not a reference to the Archie comic book series, "Veronica" and "Jughead" are characters in the series, thus referencing their predecessor.

In the summer of 1993, no search engine existed for the web, though numerous specialized catalogues were maintained by hand. Oscar Nierstrasz at the University of Geneva wrote a series of Perl scripts that periodically mirrored these pages and rewrote them into a standard format. This formed the basis for W3Catalog, the web's first primitive search engine, released on September 2nd, 1993.[7]

In June 1993, Matthew Gray, then at MIT, produced what was probably the first web robot, the Perl-based World Wide Web Wanderer, and used it to generate an index called 'Wandex'. The purpose of the Wanderer was to measure the size of the World Wide Web, which it did until late 1995. The web's second search engine, Aliweb, appeared in November 1993. Aliweb did not use a web robot, but instead depended on being notified by website administrators of the existence at each site of an index file in a particular format.

The National Center for Supercomputing Applications' Mosaic™ web browser wasn't the first to exist, but it was the first to make a major splash.[8] In November 1993, Mosaic v1.0 broke away from the small pack of existing browsers by including features like icons, bookmarks, a more attractive interface and pictures—that made the software easy to use and appealing to "non-geeks."

JumpStation (created in December 1993[9] by Jonathon Fletcher) used a web robot to find web pages and to build its index, and used a web form as the interface to its query program. It was, thus, the first WWW resource-discovery tool to combine the three essential features of a web search engine (crawling, indexing and searching) as described below. Because of the limited resources available on the platform it ran on, its indexing was limited to the titles and headings found in the web pages the crawler encountered, with such limits naturally extending to the searches performed on it as well.

One of the first "all text" crawler-based search engines was WebCrawler, which came out in 1994. Unlike its predecessors, it allowed users to search for any word on any webpage, which has long been the standard for all major search engines of the modern era. It was also the first one widely known by the public. Later in 1994, Lycos (which started at Carnegie Mellon University) was launched and became a major commercial endeavor in the field.

Soon after, many search engines appeared and vied for popularity. These included Magellan, Excite, Infoseek, Inktomi, Northern Light, and AltaVista. Yahoo! was among the most popular ways for people to find web pages of interest, but its search function operated on its web directory, rather than its full-text copies of web pages. Information seekers could also browse the directory instead of doing a keyword-based search.

In 1996, Netscape was looking to give an exclusive deal to a single search engine to appear as the featured search engine in their eponymous web browser. There was so much interest that instead Netscape struck deals with five of the major search engines: for $5 million/year, each search engine would be in rotation on the Netscape search engine page. The five engines were: Yahoo!, Magellan, Lycos, Infoseek, and Excite.[10][11]

Google adopted the idea of selling search terms in 1998, from a small search engine company named goto.com. This move had a significant effect on the SE business, which went from struggling to one of the most profitable businesses in the internet.[12]

Search engines were also known as some of the brightest stars in the Internet investing frenzy that occurred in the late 1990s.[13] Several companies entered the market spectacularly, receiving record gains during their initial public offerings. Some have taken down their public search engine, and are marketing enterprise-only editions, such as Northern Light. Many search engine companies were caught up in the dot-com bubble, a speculation-driven market boom that peaked in 1999 and ended in 2001.

- Around 2000, Google's search engine rose to prominence.[14] The company achieved better results for many searches with an innovation called PageRank, as was explained in the paper Anatomy of a Search Engine written by Sergey Brin and Larry Page, the later founders of Google.[15] This iterative algorithm ranks web pages based on the number and PageRank of other web sites and pages that link there, on the premise that good or desirable pages are linked to more than others. Google also maintained a minimalist interface to its search engine. In contrast, many of its competitors embedded a search engine in a web portal. In fact, Google search engine became so popular that spoof engines emerged such as Mystery Seeker.

By 2000, Yahoo! was providing search services based on Inktomi's search engine. Yahoo! acquired Inktomi in 2002, and Overture (which owned AlltheWeb and AltaVista) in 2003. Yahoo! switched to Google's search engine until 2004, when it launched its own search engine based on the combined technologies of its acquisitions.

Microsoft first launched MSN Search in the fall of 1998 using search results from Inktomi. In early 1999 the site began to display listings from Looksmart, blended with results from Inktomi. For a short time in 1999, MSN Search used results from AltaVista instead. In 2004, Microsoft began a transition to its own search technology, powered by its own web crawler (called msnbot).

Microsoft's rebranded search engine, Bing, was launched on June 1, 2009. On July 29, 2009, Yahoo! and Microsoft finalized a deal in which Yahoo! Search would be powered by Microsoft Bing technology.

Approach

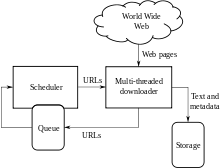

[edit | edit source]A search engine maintains the following processes in near real time:

- Web crawling

- Indexing

- Searching[16]

Web search engines get their information by web crawling from site to site. The "spider" checks for the standard filename robots.txt, addressed to it, before sending certain information back to be indexed depending on many factors, such as the titles, page content, JavaScript, Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), headings, as evidenced by the standard HTML markup of the informational content, or its metadata in HTML meta tags. "[N]o web crawler may actually crawl the entire reachable web. Due to infinite websites, spider traps, spam, and other exigencies of the real web, crawlers instead apply a crawl policy to determine when the crawling of a site should be deemed sufficient. Some sites are crawled exhaustively, while others are crawled only partially".[17]

Indexing means associating words and other definable tokens found on web pages to their domain names and HTML-based fields. The associations are made in a public database, made available for web search queries. A query from a user can be a single word. The index helps find information relating to the query as quickly as possible.[16] Some of the techniques for indexing, and caching are trade secrets, whereas web crawling is a straightforward process of visiting all sites on a systematic basis.

Between visits by the spider, the cached version of page (some or all the content needed to render it) stored in the search engine working memory is quickly sent to an inquirer. If a visit is overdue, the search engine can just act as a web proxy instead. In this case the page may differ from the search terms indexed.[16] The cached page holds the appearance of the version whose words were indexed, so a cached version of a page can be useful to the web site when the actual page has been lost, but this problem is also considered a mild form of linkrot.

Typically when a user enters a query into a search engine it is a few keywords.[18] The index already has the names of the sites containing the keywords, and these are instantly obtained from the index. The real processing load is in generating the web pages that are the search results list: Every page in the entire list must be weighted according to information in the indexes.[16] Then the top search result item requires the lookup, reconstruction, and markup of the snippets showing the context of the keywords matched. These are only part of the processing each search results web page requires, and further pages (next to the top) require more of this post processing.

Beyond simple keyword lookups, search engines offer their own GUI- or command-driven operators and search parameters to refine the search results. These provide the necessary controls for the user engaged in the feedback loop users create by filtering and weighting while refining the search results, given the initial pages of the first search results. For example, from 2007 the Google.com search engine has allowed one to filter by date by clicking "Show search tools" in the leftmost column of the initial search results page, and then selecting the desired date range.[19] It's also possible to weight by date because each page has a modification time. Most search engines support the use of the boolean operators AND, OR and NOT to help end users refine the search query. Boolean operators are for literal searches that allow the user to refine and extend the terms of the search. The engine looks for the words or phrases exactly as entered. Some search engines provide an advanced feature called proximity search, which allows users to define the distance between keywords.[16] There is also concept-based searching where the research involves using statistical analysis on pages containing the words or phrases you search for. As well, natural language queries allow the user to type a question in the same form one would ask it to a human.[20] A site like this would be ask.com.[21]

The usefulness of a search engine depends on the relevance of the result set it gives back. While there may be millions of web pages that include a particular word or phrase, some pages may be more relevant, popular, or authoritative than others. Most search engines employ methods to rank the results to provide the "best" results first. How a search engine decides which pages are the best matches, and what order the results should be shown in, varies widely from one engine to another.[16] The methods also change over time as Internet usage changes and new techniques evolve. There are two main types of search engine that have evolved: one is a system of predefined and hierarchically ordered keywords that humans have programmed extensively. The other is a system that generates an "inverted index" by analyzing texts it locates. This first form relies much more heavily on the computer itself to do the bulk of the work.

Most Web search engines are commercial ventures supported by advertising revenue and thus some of them allow advertisers to have their listings ranked higher in search results for a fee. Search engines that do not accept money for their search results make money by running search related ads alongside the regular search engine results. The search engines make money every time someone clicks on one of these ads.[22]

Market share

[edit | edit source]Google is the world's most popular search engine, with a market share of 74.52 percent as of February, 2018.[23]

The world's most popular search engines (with >1% market share) are:

| Search engine | Market share (as of February 2018) | |

|---|---|---|

| — | Template:Bartable | |

| Bing | Template:Bartable | |

| Baidu | Template:Bartable | |

| Yahoo! | Template:Bartable | |

East Asia and Russia

[edit | edit source]In some East Asian countries and Russia, Google is not the most popular search engine.

In Russia, Yandex commands a marketshare of 61.9 percent, compared to Google's 28.3 percent.[24] In China, Baidu is the most popular search engine.[25] South Korea's homegrown search portal, Naver, is used for 70 percent of online searches in the country.[26] Yahoo! Japan and Yahoo! Taiwan are the most popular avenues for internet search in Japan and Taiwan, respectively.[27]

Europe

[edit | edit source]Markets in Western Europe are mostly dominated by Google, with some exceptions such as the Czech Republic, where Seznam is a strong competitor.[28]

Search engine bias

[edit | edit source]Although search engines are programmed to rank websites based on some combination of their popularity and relevancy, empirical studies indicate various political, economic, and social biases in the information they provide[29][30] and the underlying assumptions about the technology.[31] These biases can be a direct result of economic and commercial processes (e.g., companies that advertise with a search engine can become also more popular in its organic search results), and political processes (e.g., the removal of search results to comply with local laws).[32] For example, Google will not surface certain neo-Nazi websites in France and Germany, where Holocaust denial is illegal.

Biases can also be a result of social processes, as search engine algorithms are frequently designed to exclude non-normative viewpoints in favor of more "popular" results.[33] Indexing algorithms of major search engines skew towards coverage of U.S.-based sites, rather than websites from non-U.S. countries.[30]

Google Bombing is one example of an attempt to manipulate search results for political, social or commercial reasons.

Several scholars have studied the cultural changes triggered by search engines,[34] and the representation of certain controversial topics in their results, such as terrorism in Ireland[35] and conspiracy theories.[36]

Customized results and filter bubbles

[edit | edit source]Many search engines such as Google and Bing provide customized results based on the user's activity history. This leads to an effect that has been called a filter bubble. The term describes a phenomenon in which websites use algorithms to selectively guess what information a user would like to see, based on information about the user (such as location, past click behaviour and search history). As a result, websites tend to show only information that agrees with the user's past viewpoints, effectively isolating the user in a bubble that tends to exclude contrary information. Prime examples are Google's personalized search results and Facebook's personalized news stream. According to Eli Pariser, who coined the term, users get less exposure to conflicting viewpoints and are isolated intellectually in their own informational bubble. Pariser relayed an example in which one user searched Google for "BP" and got investment news about British Petroleum while another searcher got information about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and that the two search results pages were "strikingly different".[37][38][39] The bubble effect may have negative implications for civic discourse, according to Pariser.[40] Since this problem has been identified, competing search engines have emerged that seek to avoid this problem by not tracking or "bubbling" users, such as DuckDuckGo. Other scholars do not share Pariser's view, finding the evidence in support of his thesis unconvincing.[41]

Christian, Islamic and Jewish search engines

[edit | edit source]The global growth of the Internet and electronic media in the Arab and Muslim World during the last decade has encouraged Islamic adherents in the Middle East and Asian sub-continent, to attempt their own search engines, their own filtered search portals that would enable users to perform safe searches. More than usual safe search filters, these Islamic web portals categorizing websites into being either "halal" or "haram", based on modern, expert, interpretation of the "Law of Islam". ImHalal came online in September 2011. Halalgoogling came online in July 2013. These use haram filters on the collections from Google and Bing (and others).[42]

While lack of investment and slow pace in technologies in the Muslim World has hindered progress and thwarted success of an Islamic search engine, targeting as the main consumers Islamic adherents, projects like Muxlim, a Muslim lifestyle site, did receive millions of dollars from investors like Rite Internet Ventures, and it also faltered. Other religion-oriented search engines are Jewgle, the Jewish version of Google, and SeekFind.org, which is Christian. SeekFind filters sites that attack or degrade their faith.[43]

Search engine submission

[edit | edit source]Search engine submission is a process in which a webmaster submits a website directly to a search engine. While search engine submission is sometimes presented as a way to promote a website, it generally is not necessary because the major search engines use web crawlers, that will eventually find most web sites on the Internet without assistance. They can either submit one web page at a time, or they can submit the entire site using a sitemap, but it is normally only necessary to submit the home page of a web site as search engines are able to crawl a well designed website. There are two remaining reasons to submit a web site or web page to a search engine: to add an entirely new web site without waiting for a search engine to discover it, and to have a web site's record updated after a substantial redesign.

Some search engine submission software not only submits websites to multiple search engines, but also add links to websites from their own pages. This could appear helpful in increasing a website's ranking, because external links are one of the most important factors determining a website's ranking. However, John Mueller of Google has stated that this "can lead to a tremendous number of unnatural links for your site" with a negative impact on site ranking.[44]

See also

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Harrenstien, Ken; White, Vic (March 1, 1982). "RFC 812 - NICNAME/WHOIS". Internet Engineering Task Force. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Knowbot programming: System support for mobile agents". Corporation for National Research Initiatives.

- ↑ Deutsch, Peter (September 11, 1990). "[next] An Internet archive server server (was about Lisp) - comp.archives". Google Groups. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ↑ "World-Wide Web Servers". World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ↑ "What's New! February 1994". Mosaic Communications Corporation. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Internet History - Search Engines (from Search Engine Watch)". Universiteit Leiden. September 2001. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ↑ Nierstrasz, Oscar (September 2, 1993). "Searchable Catalog of WWW Resources (experimental)". Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Enabling Discovery - NCSA Mosaic". National Center for Supercomputing Applications. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021.

- ↑ "What's New, December 1993". National Center for Supercomputing Applications. December 28, 1993. Archived from the original on January 17, 2006. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Yahoo! And Netscape Ink International Distribution Deal". Yahoo!. July 8, 1997. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Browser Deals Push Netscape Stock Up 7.8%". Los Angeles Times. April 1, 1996. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Pursel, Bart. "Search Engines". Penn State Pressbooks. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ↑ Gandal, Neil (2001). "The dynamics of competition in the internet search engine market". International Journal of Industrial Organization. 19 (7): 1103–1117. doi:10.1016/S0167-7187(01)00065-0.

- ↑ "Our History in depth". W3.org. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- ↑ Brin, Sergey; Page, Larry. "The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine" (PDF).

- ↑ a b c d e f Jawadekar, Waman S (2011), "8. Knowledge Management: Tools and Technology", Knowledge Management: Text & Cases, New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill Education Private Ltd, p. 278, ISBN 978-0-07-07-0086-4, retrieved November 23, 2012

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ↑ Dasgupta, Anirban; Ghosh, Arpita; Kumar, Ravi; Olston, Christopher; Pandey, Sandeep; and Tomkins, Andrew. The Discoverability of the Web. http://www.arpitaghosh.com/papers/discoverability.pdf

- ↑ Jansen, B. J., Spink, A., and Saracevic, T. 2000. Real life, real users, and real needs: A study and analysis of user queries on the web. Information Processing & Management. 36(2), 207-227.

- ↑ Chitu, Alex (August 30, 2007). "Easy Way to Find Recent Web Pages". Google Operating System. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ "Versatile question answering systems: seeing in synthesis", Mittal et al., IJIIDS, 5(2), 119-142, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.ask.com. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ↑ "FAQ". RankStar. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ "Desktop Search Engine Market Share". NetMarketShare. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ "Live Internet - Site Statistics". Live Internet. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ↑ Arthur, Charles (2014-06-03). "The Chinese technology companies poised to dominate the world". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/03/chinese-technology-companies-huawei-dominate-world. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ↑ "How Naver Hurts Companies' Productivity". The Wall Street Journal. 2014-05-21. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ↑ "Age of Internet Empires". Oxford Internet Institute. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ↑ Seznam Takes on Google in the Czech Republic. Doz.

- ↑ Segev, El (2010). Google and the Digital Divide: The Biases of Online Knowledge, Oxford: Chandos Publishing.

- ↑ a b Vaughan, Liwen; Mike Thelwall (2004). "Search engine coverage bias: evidence and possible causes". Information Processing & Management. 40 (4): 693–707. doi:10.1016/S0306-4573(03)00063-3.

- ↑ Jansen, B. J. and Rieh, S. (2010) The Seventeen Theoretical Constructs of Information Searching and Information Retrieval. Journal of the American Society for Information Sciences and Technology. 61(8), 1517-1534.

- ↑ Berkman Center for Internet & Society (2002), "Replacement of Google with Alternative Search Systems in China: Documentation and Screen Shots", Harvard Law School.

- ↑ Introna, Lucas; Helen Nissenbaum (2000). "Shaping the Web: Why the Politics of Search Engines Matters". The Information Society: An International Journal. 16 (3). doi:10.1080/01972240050133634.

- ↑ Hillis, Ken; Petit, Michael; Jarrett, Kylie (2012-10-12). Google and the Culture of Search. Routledge. ISBN 9781136933066.

- ↑ Reilly, P. (2008-01-01). Spink, Prof Dr Amanda; Zimmer, Michael (eds.). ‘Googling’ Terrorists: Are Northern Irish Terrorists Visible on Internet Search Engines?. Information Science and Knowledge Management. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 151–175. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-75829-7_10. ISBN 978-3-540-75828-0.

- ↑ Ballatore, A. "Google chemtrails: A methodology to analyze topic representation in search engines". First Monday.

- ↑ Parramore, Lynn (10 October 2010). "The Filter Bubble". The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/daily-dish/archive/2010/10/the-filter-bubble/181427/. Retrieved 2011-04-20. "Since Dec. 4, 2009, Google has been personalized for everyone. So when I had two friends this spring Google "BP," one of them got a set of links that was about investment opportunities in BP. The other one got information about the oil spill...."

- ↑ Weisberg, Jacob (10 June 2011). "Bubble Trouble: Is Web personalization turning us into solipsistic twits?". Slate. http://www.slate.com/id/2296633/. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ↑ Gross, Doug (May 19, 2011). "What the Internet is hiding from you". CNN. http://edition.cnn.com/2011/TECH/web/05/19/online.privacy.pariser/. Retrieved 2011-08-15. "I had friends Google BP when the oil spill was happening. These are two women who were quite similar in a lot of ways. One got a lot of results about the environmental consequences of what was happening and the spill. The other one just got investment information and nothing about the spill at all."

- ↑ Zhang, Yuan Cao; Séaghdha, Diarmuid Ó; Quercia, Daniele; Jambor, Tamas (February 2012). "Auralist: Introducing Serendipity into Music Recommendation" (PDF). ACM WSDM.

- ↑ O'Hara, K. (2014-07-01). "In Worship of an Echo". IEEE Internet Computing. 18 (4): 79–83. doi:10.1109/MIC.2014.71. ISSN 1089-7801.

- ↑ "New Islam-approved search engine for Muslims". News.msn.com. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

- ↑ "Halalgoogling: Muslims Get Their Own "sin free" Google; Should Christians Have Christian Google? - Christian Blog". Christian Blog.

- ↑ Schwartz, Barry (2012-10-29). "Google: Search Engine Submission Services Can Be Harmful". Search Engine Roundtable. https://www.seroundtable.com/search-engine-submission-google-15906.html. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

Further reading

[edit | edit source]- Steve Lawrence; C. Lee Giles (1999). "Accessibility of information on the web". Nature. 400 (6740): 107–9. doi:10.1038/21987. PMID 10428673.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|quotes=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bing Liu (2007), Web Data Mining: Exploring Hyperlinks, Contents and Usage Data. Springer,ISBN 3-540-37881-2

- Bar-Ilan, J. (2004). The use of Web search engines in information science research. ARIST, 38, 231-288.

- Levene, Mark (2005). An Introduction to Search Engines and Web Navigation. Pearson.

- Hock, Randolph (2007). The Extreme Searcher's Handbook.ISBN 978-0-910965-76-7

- Javed Mostafa (February 2005). "Seeking Better Web Searches". Scientific American.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|quotes=(help) - Ross, Nancy; Wolfram, Dietmar (2000). "End user searching on the Internet: An analysis of term pair topics submitted to the Excite search engine". Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 51 (10): 949–958. doi:10.1002/1097-4571(2000)51:10<949::AID-ASI70>3.0.CO;2-5.

- Xie, M.; et al. (1998). "Quality dimensions of Internet search engines". Journal of Information Science. 24 (5): 365–372. doi:10.1177/016555159802400509.

- Information Retrieval: Implementing and Evaluating Search Engines. MIT Press. 2010.

External links

[edit | edit source]