Understanding Air Safety in the Jet Age/Bad Design, Bad Maintenance - TWA 800

The investigation that followed the midair explosion of TWA 800 on 17 July 1996 would be the longest, most complex and expensive in U.S. history. It would also prove to be controversial and give rein to accusations of cover-up and conspiracy. Ultimately though, the disaster would be shown to be due to the most prosaic of causes: bad design and shoddy maintenance.

Trans World Airlines Flight 800 was a Boeing 747-131. The aircraft, registration N93119, was manufactured in July 1971; it had been ordered by Eastern Air Lines, but after Eastern canceled its 747 orders, the plane was purchased new by Trans World Airlines. It had completed 16,869 flights with 93,303 hours of operation. The day of the accident, the plane departed from Athens and arrived at John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) where it was refueled and the crew changed. The crew for the upcoming flight was 58-year-old Captain Ralph G. Kevorkian, with 18,800 flight hours, 57-year-old Captain/Check Airman Steven E. Snyder with 17,000 flight hours, and 63-year-old Flight Engineer/Check Airman Richard G. Campbell, as well as 25-year-old flight engineer trainee Oliver Krick, who was starting the sixth leg of his initial operating experience training. While Snyder was officially the captain, the planned flight was a training flight for Kevorkian and he was, therefore, seated in the captain's (left) seat.

The ground-maintenance crew locked out the thrust reverser for engine #3 because of technical problems with the thrust reverser sensors during the inbound landing at JFK, prior to Flight 800's departure. Additionally, severed cables for the engine #3 thrust reverser were replaced. During refueling of the aircraft, the volumetric shutoff (VSO) control was believed to have been triggered before the tanks were full. To continue the pressure fueling, a TWA mechanic overrode the automatic VSO by pulling the volumetric fuse and an overflow circuit breaker. Maintenance records indicate that the airplane had numerous VSO-related maintenance writeups in the weeks before the accident.

TWA 800 was scheduled to depart JFK for Charles de Gaulle Airport around 7:00 p.m., but the flight was delayed until 8:02 p.m. by a disabled piece of ground equipment and a passenger/baggage mismatch. After the owner of the baggage in question was confirmed to be on board, the flight crew prepared for departure and the aircraft pushed back from Gate 27 at the TWA Flight Center. The flight crew started the engines at 8:04 pm. however, because of the previous maintenance undertaken on engine #3, the flight crew only started engines #1, #2, and #4. Engine #3 was started ten minutes later at 8:14 pm. Taxi and takeoff proceeded uneventfully.

TWA 800 then received a series of heading changes and generally increasing altitude assignments as it climbed to its intended cruising altitude. Weather in the area was benign with light winds and scattered clouds. The last radio transmission from the airplane occurred at 8:30 p.m. when the flight crew received and then acknowledged instructions from Boston Air Route Traffic Control Center to climb to 15,000 ft. The last recorded radar transponder return from the airplane was recorded by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) radar site at Trevose, Pennsylvania at 8:31:12 p.m.

What happened next stunned onlookers. Thirty-eight seconds after the last contact the captain of an Eastwind Airlines Boeing 737 reported to Boston ARTCC that he "just saw an explosion out here", adding, "we just saw an explosion up ahead of us here... about 16,000 ft or something like that, it just went down into the water." Subsequently, many air traffic control facilities in the New York/Long Island area received reports of an explosion from other pilots operating in the area. Many witnesses in the vicinity of the crash stated that they saw or heard explosions, accompanied by a large fireball or fireballs over the ocean, and observed debris, some of which was burning while falling into the water.

Various civilian, military, and police vessels reached the crash site and searched for survivors within minutes of the initial water impact, but found none, making TWA 800 the second-deadliest aircraft accident in United States history at that time.

The NTSB was notified about 8:50 p.m. the day of the accident; a full "go team" was assembled in Washington, D.C. and arrived on scene early the next morning. Meanwhile, initial witness descriptions led many to believe the cause of the crash was a bomb or surface-to-air missile attack. Given the potential for criminal causes, the FBI initiated a parallel investigation alongside the NTSB's accident investigation.

The search-and-rescue began immediately: a helicopter of the New York Air National Guard saw the explosion from approximately eight miles away, and arrived on scene so quickly that debris was still raining down, and the aircraft had to pull away. They reported their sighting to the tower at Suffolk County Airport. Later, remote-operated vehicles (ROVs), side-scan sonar, and laser line-scanning equipment were used to search for and investigate underwater debris fields. Victims and wreckage were recovered by scuba divers and ROVs; later scallop trawlers were used to recover wreckage embedded in the sea floor. In one of the largest diver-assisted salvage operations ever conducted, often working in very difficult and dangerous conditions, over 95% of the airplane wreckage was eventually recovered. The search and recovery effort identified three main areas of wreckage underwater :the yellow zone, red zone, and green zone contained wreckage from front, center, and rear sections of the airplane, respectively. The green zone with the tail section of the aircraft was located the furthest along the flight path.:71–74

Pieces of wreckage were transported by boat to shore and then by truck to leased hangar space at the former Grumman Aircraft facility in Calverton, New York, for storage, examination, and reconstruction.[1]:63 This facility became the command center and headquarters for the investigation.[1]:363–365 NTSB and FBI personnel were present to observe all transfers to preserve the evidentiary value of the wreckage.[1]:367 The cockpit voice recorder and flight data recorder were recovered by U.S. Navy divers one week after the accident; they were immediately shipped to the NTSB laboratory in Washington, D.C., for readout.[1]:58 The victims' remains were transported to the Suffolk County Medical Examiner's Office in Hauppauge, New York.[2]:2

Tensions in the investigation

[edit | edit source]Relatives of TWA 800 passengers and crew, as well as the media, gathered at the Ramada Plaza JFK Hotel.[3] Many waited until the remains of their family members had been recovered, identified, and released.[4]:1[5]:3–4 This hotel became known as the "Heartbreak Hotel" for its role in handling families of victims of several airliner crashes.[6][7][8]

Grief turned to anger at TWA's delay in confirming the passenger list,[3] conflicting information from agencies and officials,[9]:1 and mistrust of the recovery operation's priorities.[10]:2 Although NTSB vice chairman Robert Francis stated that all bodies were being retrieved as soon as they were spotted, and that wreckage was being recovered only if divers believed that victims were hidden underneath,[10]:2 many families were suspicious that investigators were not being truthful, or withholding information.[10]:2[11]:7[9]:1–2

Much anger and political pressure was also directed at Suffolk County Medical Examiner Dr. Charles V. Wetli as recovered bodies backlogged at the morgue.[12]:3[11]:5[9]:1–2 Under constant and considerable pressure to identify victims with minimal delay,[2]:3 pathologists worked non-stop.[11]:5 Since the primary objective was to identify all remains rather than performing a detailed forensic autopsy, the thoroughness of the examinations was highly variable.[2]:3 Ultimately, remains of all 230 victims were recovered and identified, the last over 10 months after the crash.[2]:2

With lines of authority unclear, differences in agendas and culture between the FBI and NTSB resulted in discord.[11]:1 The FBI, from the start assuming that a criminal act had occurred,[11]:3 saw the NTSB as indecisive. Expressing frustration at the NTSB's unwillingness to speculate on a cause, one FBI agent described the NTSB as "No opinions. No nothing."[11]:4 Meanwhile, the NTSB was required to refute or play down speculation about conclusions and evidence, frequently supplied to reporters by law enforcement officials and politicians.[12]:3[11]:4 The International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, an invited party to the NTSB investigation, criticized the undocumented removal by FBI agents of wreckage from the hangar where it was stored.[13]

Witness interviews

[edit | edit source]

Although there were considerable discrepancies between different accounts, most witnesses to the accident had seen a "streak of light" that was described by 38 of 258 witnesses as ascending,[1]:232 moving to a point where a large fireball appeared, with several witnesses reporting that the fireball split in two as it descended toward the water.[1]:3 There was intense public interest in these witness reports and much speculation that the reported streak of light was a missile that had struck TWA 800, causing the airplane to explode.[1]:262 These witness accounts were a major reason for the initiation and duration of the FBI's criminal investigation.[15]:5

Approximately 80 FBI agents conducted interviews with potential witnesses daily.[15]:7 No verbatim records of the witness interviews were produced; instead, the agents who conducted the interviews wrote summaries that they then submitted.[15]:5 Witnesses were not asked to review or correct the summaries.[15]:5 Included in some of the witness summaries were drawings or diagrams of what the witness observed. Witnesses were not allowed to testify at the court hearings.[14]:165[16]:184

Within days of the crash the NTSB announced its intent to form its own witness group and to interview witnesses to the crash.[15]:6 After the FBI raised concerns about non-governmental parties in the NTSB's investigation having access to this information and possible prosecutorial difficulties resulting from multiple interviews of the same witness,[15]:6 the NTSB deferred and did not interview witnesses to the crash. A Safety Board investigator later reviewed FBI interview notes and briefed other Board investigators on their contents. In November 1996, the FBI agreed to allow the NTSB access to summaries of witness accounts in which personally identifying information had been redacted and to conduct a limited number of witness interviews. In April 1998, the FBI provided the NTSB with the identities of the witnesses but due to the time elapsed a decision was made to rely on the original FBI documents rather than reinterview witnesses.[1]:229

Further investigation and analysis

[edit | edit source]Examination of the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and flight data recorder data showed a normal takeoff and climb,[17]:4 with the aircraft in normal flight[18]:2 before both abruptly stopped at 8:31:12 pm.[1]:3 At 8:29:15 pm, Captain Kevorkian was heard to say, "Look at that crazy fuel flow indicator there on number four... see that?"[1]:2 A loud noise recorded on the last few tenths of a second of the CVR was similar to the last noises recorded from other airplanes that had experienced in-flight breakups.[1]:256 This, together with the distribution of wreckage and witness reports, all indicated a sudden catastrophic in-flight breakup of TWA 800.[1]:256

Possible causes of the in-flight breakup

[edit | edit source]Investigators considered several possible causes for the structural breakup: structural failure and decompression, detonation of a high-energy explosive device, such as a missile warhead exploding either upon impact with the airplane, or just before impact, a bomb exploding inside the airplane, or a fuel-air explosion in the center wing fuel tank.[1]:256–257

Structural failure and decompression

[edit | edit source]Close examination of the wreckage revealed no evidence of structural faults such as fatigue, corrosion or mechanical damage that could have caused the in-flight breakup.[1]:257 It was also suggested that the breakup could have been initiated by an in-flight separation of the forward cargo door like the disasters on board Turkish Airlines Flight 981 or United Airlines Flight 811, but all evidence indicated that the door was closed and locked at impact.[1]:257 The NTSB concluded that "the in-flight breakup of TWA flight 800 was not initiated by a preexisting condition resulting in a structural failure and decompression."[1]:257

Missile or bomb detonation

[edit | edit source]A review of recorded data from long-range and airport surveillance radars revealed multiple contacts of airplanes or objects in TWA 800's vicinity at the time of the accident.[1]:87–89 None of these contacts intersected TWA 800's position at any time.[1]:89 Attention was drawn to data from the Islip, New York, ARTCC facility that showed three tracks in the vicinity of TWA 800 that did not appear in any of the other radar data.[1]:93 None of these sequences intersected TWA 800's position at any time either.[1]:93 All the reviewed radar data showed no radar returns consistent with a missile or other projectile traveling toward TWA 800.[1]:89

The NTSB addressed allegations that the Islip radar data showed groups of military surface targets converging in a suspicious manner in an area around the accident, and that a 30-knot radar track, never identified and 3 nautical miles from the crash site, was involved in foul play, as evidenced by its failure to divert from its course and assist with the search and rescue operations.[1]:93 Military records examined by the NTSB showed no military surface vessels within 15 NM of TWA 800 at the time of the accident.[1]:93 In addition, the records indicated that the closest area scheduled for military use, warning area W-387A/B, was 160 NM south.[1]:93

The NTSB reviewed the 30-knot target track to try to determine why it did not divert from its course and proceed to the area where the TWA 800 wreckage had fallen. TWA 800 was behind the target, and with the likely forward-looking perspective of the target's occupant(s), the occupants would not have been in a position to observe the aircraft's breakup or subsequent explosions or fireball(s).[1]:94 Additionally, it was unlikely that the occupants of the target track would have been able to hear the explosions over the sound of its engines and the noise of the hull traveling through water, even more so if the occupants were in an enclosed bridge or cabin.[1]:94 Further, review of the Islip radar data for other similar summer days and nights in 1999 indicated that the 30-knot track was consistent with normal commercial fishing, recreational, and cargo vessel traffic.[1]:94

- Recorded radar data

-

Radar data showing vehicle and/or object tracks within 10 NM of TWA flight 800 just before the accident.[1](fig. 25, p. 90)

-

Three sequences of primary returns near TWA 800 that were only recorded by the Islip radar.[1](fig. 26, p. 91)

-

Primary radar returns that appeared near the TWA 800 after 8:31:12 pm. The 30-knot track is at the bottom center of the image.[1](fig. 27, p. 92)

Trace amounts of explosive residue were detected on three samples of material from three separate locations of the recovered airplane wreckage (described by the FBI as a piece of canvas-like material and two pieces of a floor panel).[1]:118 These samples were submitted to the FBI's laboratory in Washington, D.C., which determined that one sample contained traces of cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine (RDX), another nitroglycerin, and the third a combination of RDX and pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN);[1]:118 these findings received much media attention at the time.[19][20] In addition, the backs of several damaged passenger seats were observed to have an unknown red/brown-shaded substance on them.[1]:118 According to the seat manufacturer, the locations and appearance of this substance were consistent with adhesive used in the construction of the seats, and additional laboratory testing by NASA identified the substance as being consistent with adhesives.[1]:118

Further examination of the airplane structure, seats, and other interior components found no damage typically associated with a high-energy explosion of a bomb or missile warhead ("severe pitting, cratering, petalling, or hot gas washing").[1]:258 This included the pieces on which trace amounts of explosives were found.[1]:258 Of the 5 percent of the fuselage that was not recovered, none of the missing areas were large enough to have covered all the damage that would have been caused by the detonation of a bomb or missile.[1]:258 None of the victims' remains showed any evidence of injuries that could have been caused by high-energy explosives.[1]:258

The NTSB considered the possibility that the explosive residue was due to contamination from the aircraft's use in 1991 transporting troops during the Gulf War or its use in a dog-training explosive detection exercise about one month before the accident.[1]:258–259 Testing conducted by the FAA's Technical Center indicated that residues of the type of explosives found on the wreckage would dissipate completely after two days of immersion in sea water (almost all recovered wreckage was immersed longer than two days).[1]:259 The NTSB concluded that it was "quite possible" that the explosive residue detected was transferred from military ships or ground vehicles, or the clothing and boots of military personnel, onto the wreckage during or after the recovery operation and was not present when the aircraft crashed into the water.[1]:259

Although it was unable to determine the exact source of the trace amounts of explosive residue found on the wreckage, the lack of any other corroborating evidence associated with a high-energy explosion led the NTSB to conclude that "the in-flight breakup of TWA flight 800 was not initiated by a bomb or missile strike."[1]:259

Fuel-air explosion in the center wing fuel tank

[edit | edit source]

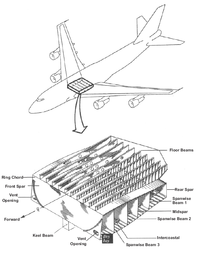

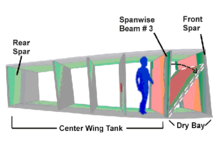

In order to evaluate the sequence of structural breakup of the airplane, the NTSB formed the Sequencing Group,[1]:100 which examined individual pieces of the recovered structure, two-dimensional reconstructions or layouts of sections of the airplane, and various-sized three-dimensional reconstructions of portions of the airplane.[1]:100 In addition, the locations of pieces of wreckage at the time of recovery and differences in fire effects on pieces that are normally adjacent to each other were evaluated.[1]:100 The Sequencing Group concluded that the first event in the breakup sequence was a fracture in the wing center section of the aircraft, caused by an "overpressure event" in the center wing fuel tank (CWT).[21]:29 An overpressure event was defined as a rapid increase in pressure resulting in failure of the structure of the CWT.[1]:85

Because there was no evidence that an explosive device detonated in this (or any other) area of the airplane, this overpressure event could only have been caused by a fuel/air explosion in the CWT.[1]:261 There were Template:Convert/gal of fuel in the CWT of TWA 800;[22] tests recreating the conditions of the flight showed the combination of liquid fuel and fuel/air vapor to be flammable.[1]:261 A major reason for the flammability of the fuel/air vapor in the CWT of the 747 was the large amount of heat generated and transferred to the CWT by air conditioning packs located directly below the tank;[1]:298 with the CWT temperature raised to a sufficient level, a single ignition source could cause an explosion.[1]:298

Computer modeling[1]:122–123 and scale-model testing[1]:123 were used to predict and demonstrate how an explosion would progress in a 747 CWT. During this time, quenching was identified as an issue, where the explosion would extinguish itself as it passed through the complex structure of the CWT.[1]:123 Because the research data regarding quenching was limited, a complete understanding of quenching behavior was not possible, and the issue of quenching remained unresolved.[1]:137

In order to better determine whether a fuel/air vapor explosion in the CWT would generate sufficient pressure to break apart the fuel tank and lead to the destruction of the airplane, tests were conducted in July and August 1997, using a retired Air France 747 at Bruntingthorpe Airfield, England. These tests simulated a fuel/air explosion in the CWT by igniting a propane/air mixture; this resulted in the failure of the tank structure due to overpressure.[1]:261 While the NTSB acknowledged that the test conditions at Bruntingthorpe were not fully comparable to the conditions that existed on TWA 800 at the time of the accident,[1]:261 previous fuel explosions in the CWTs of commercial airliners such as Avianca Flight 203 and Philippine Airlines Flight 143 confirmed that a CWT explosion could break apart the fuel tank and lead to the destruction of an airplane.[1]:261

Ultimately, based on "the accident airplane's breakup sequence; wreckage damage characteristics; scientific tests and research on fuels, fuel tank explosions, and the conditions in the CWT at the time of the accident; and analysis of witness information,"[1]:271 the NTSB concluded that "the TWA flight 800 in-flight breakup was initiated by a fuel/air explosion in the CWT."[1]:63

In-flight breakup sequence and crippled flight

[edit | edit source]- Debris fields

-

Map showing the locations of the red, yellow, and green zones.[1](fig.22a, p.66)

-

Wreckage found in each zone corresponded to specific areas of the aircraft.[1](fig.22b, p.67)

-

The pathways the wreckage took as it fell to the ocean.[1](fig.22c, p.68)

Recovery locations of the wreckage from the ocean (the red, yellow, and green zones) clearly indicated that: (1) the red area pieces (from the forward portion of the wing center section and a ring of fuselage directly in front) were the earliest pieces to separate from the airplane; (2) the forward fuselage section departed simultaneously with or shortly after the red area pieces, landing relatively intact in the yellow zone; (3) the green area pieces (wings and the aft portion of the fuselage) remained intact for a period after the separation of the forward fuselage, and impacted the water in the green zone.[23]

Fire damage and soot deposits on the recovered wreckage indicated that some areas of fire existed on the airplane as it continued in crippled flight after the loss of the forward fuselage.[1]:109 After about 34 seconds (based on information from witness documents), the outer portions of both the right and left wings failed.[1]:109, 263 Shortly after, the left wing separated from what remained of the main fuselage, which resulted in further development of the fuel-fed fireballs as the pieces of wreckage fell to the ocean.[1]:263

Only the FAA radar facility in North Truro, Massachusetts, using specialized processing software from the United States Air Force 84th Radar Evaluation Squadron, was capable of estimating the altitude of TWA 800 after it lost power due to the CWT explosion.[1]:87 Because of accuracy limitations, this radar data could not be used to determine whether the aircraft climbed after the nose separated.[1]:87 Instead, the NTSB conducted a series of computer simulations to examine the flightpath of the main portion of the fuselage.[1]:95–96 Hundreds of simulations were run using various combinations of possible times the nose of TWA 800 separated (the exact time was unknown), different models of the behavior of the crippled aircraft (the aerodynamic properties of the aircraft without its nose could only be estimated), and longitudinal radar data (the recorded radar tracks of the east/west position of TWA 800 from various sites differed).[1]:96–97 These simulations indicated that after the loss of the forward fuselage the remainder of the aircraft continued in crippled flight, then pitched up while rolling to the left (north),[1]:263 climbing to a maximum altitude between 15,537 and 16,678 feet (4,736 and 5,083 m)[1]:97 from its last recorded altitude, 13,760 feet (4,190 m).[1]:256

Analysis of reported witness observations

[edit | edit source]

At the start of FBI's investigation, because of the possibility that international terrorists might have been involved, assistance was requested from the CIA (US Central Intelligence Agency.[24]:2 CIA analysts, relying on sound-propagation analysis, concluded that the witnesses could not be describing a missile approaching an intact aircraft, but were seeing a trail of burning fuel coming from the aircraft after the initial explosion.[24]:5–6 This conclusion was reached after calculating how long it took for the sound of the initial explosion to reach the witnesses, and using that to correlate the witness observations with the accident sequence.[24]:5 In all cases the witnesses could not be describing a missile approaching an intact aircraft, as the plane had already exploded before their observations began.[24]:6

As the investigation progressed, the NTSB decided to form a witness group to more fully address the accounts of witnesses.[15]:7 From November 1996 through April 1997 this group reviewed summaries of witness accounts on loan from the FBI (with personal information redacted), and conducted interviews with crewmembers from a New York Air National Guard HH-60 helicopter and C-130 airplane, as well as a U.S. Navy P-3 airplane that was flying in the vicinity of TWA 800 at the time of the accident.[15]:7–8

In February 1998, the FBI, having closed its active investigation, agreed to fully release the witness summaries to the NTSB.[15]:10 With access to these documents no longer controlled by the FBI, the NTSB formed a second witness group to review the documents.[15]:10 Because of the amount of time that had elapsed (about 21 months) before the NTSB received information about the identity of the witnesses, the witness group chose not to re-interview the witnesses, but instead to rely on the original summaries of witness statements written by FBI agents as the best available evidence of the observations initially reported by the witnesses.[1]:230 Despite the two and a half years that had elapsed since the accident, the witness group did interview the captain of Eastwind Airlines Flight 507, who was the first to report the explosion of TWA 800, because of his vantage point and experience as an airline pilot.[15]:12

The NTSB's review of the released witness documents determined that they contained 736 witness accounts, of which 258 were characterized as "streak of light" witnesses ("an object moving in the sky... variously described [as] a point of light, fireworks, a flare, a shooting star, or something similar.")[1]:230 The NTSB Witness Group concluded that the streak of light reported by witnesses might have been the actual airplane during some stage of its flight before the fireball developed, noting that most of the 258 streak of light accounts were generally consistent with the calculated flightpath of the accident airplane after the CWT explosion.[1]:262

Thirty-eight witnesses described a streak of light that ascended vertically, or nearly so, and these accounts "seem[ed] to be inconsistent with the accident airplane's flightpath."[1]:265 In addition, 18 witnesses reported seeing a streak of light that originated at the surface, or the horizon, which did not "appear to be consistent with the airplane's calculated flightpath and other known aspects of the accident sequence."[1]:265 Regarding these differing accounts, the NTSB noted that based on their experience in previous investigations "witness reports are often inconsistent with the known facts or with other witnesses' reports of the same events."[1]:237 The interviews conducted by the FBI focused on the possibility of a missile attack; suggested interview questions given to FBI agents such as "Where was the sun in relation to the aircraft and the missile launch point?" and "How long did the missile fly?" could have biased interviewees' responses in some cases.[1]:266 The NTSB concluded that given the large number of witnesses in this case, they "did not expect all of the documented witness observations to be consistent with one another"[1]:269 and "did not view these apparently anomalous witness reports as persuasive evidence that some witnesses might have observed a missile."[1]:270

After missile visibility tests were conducted in April 2000, at Eglin Air Force Base, Fort Walton Beach, Florida,[1]:254 the NTSB determined that if witnesses had observed a missile attack they would have seen:

- a light from the burning missile motor ascending very rapidly and steeply for about 8 seconds;

- the light disappearing for up to 7 seconds;

- upon the missile striking the aircraft and igniting the CWT, another light, moving considerably more slowly and more laterally than the first, for about 30 seconds;

- this light descending while simultaneously developing into a fireball falling toward the ocean.[1]:270 None of the witness documents described such a scenario.[1]:270

Because of their unique vantage points or the level of precision and detail provided in their accounts, five witness accounts generated special interest:[1]:242–243 the pilot of Eastwind Airlines Flight 507, the crew members in the HH-60 helicopter, a streak-of-light witness aboard US Airways Flight 217, a land witness on the Beach Lane Bridge in Westhampton Beach, New York, and a witness on a boat near Great Gun Beach.[1]:243–247 Advocates of a missile-attack scenario asserted that some of these witnesses observed a missile;[1]:264 analysis demonstrated that the observations were not consistent with a missile attack on TWA 800, but instead were consistent with these witnesses having observed part of the in-flight fire and breakup sequence after the CWT explosion.[1]:264

The NTSB concluded that "the witness observations of a streak of light were not related to a missile and that the streak of light reported by most of these witnesses was burning fuel from the accident airplane in crippled flight during some portion of the post-explosion, preimpact breakup sequence".[1]:270 The NTSB further concluded that "the witnesses' observations of one or more fireballs were of the airplane's burning wreckage falling toward the ocean".[1]:270

Possible ignition sources of the center wing fuel tank

[edit | edit source]To determine what ignited the flammable fuel-air vapor in the CWT and caused the explosion, the NTSB evaluated numerous potential ignition sources. All but one were considered very unlikely to have been the source of ignition.[1]:279

Missile fragment or small explosive charge

[edit | edit source]Although the NTSB had already reached the conclusion that a missile strike did not cause the structural failure of the airplane, the possibility that a missile could have exploded close enough to TWA 800 for a missile fragment to have entered the CWT and ignited the fuel/air vapor, yet far enough away not to have left any damage characteristic of a missile strike, was considered.[1]:272 Computer simulations using missile performance data simulated a missile detonating in a location such that a fragment from the warhead could penetrate the CWT.[1]:273 Based on these simulations, the NTSB concluded that it was "very unlikely" that a warhead detonated in such a location where a fragment could penetrate the CWT, but no other fragments impact the surrounding airplane structure leaving distinctive impact marks.[1]:273

Similarly, the investigation considered the possibility that a small explosive charge placed on the CWT could have been the ignition source.[1]:273 Testing by the NTSB and the British Defence Evaluation and Research Agency demonstrated that when metal of the same type and thickness of the CWT was penetrated by a small charge, there was petalling of the surface where the charge was placed, pitting on the adjacent surfaces, and visible hot gas washing damage in the surrounding area.[1]:273–274 Since none of the recovered CWT wreckage exhibited these damage characteristics, and none of the areas of missing wreckage were large enough to encompass all the expected damage, the investigation concluded that this scenario was "very unlikely."[1]:274

Other potential sources

[edit | edit source]The NTSB also investigated whether the fuel/air mixture in the CWT could have been ignited by lightning strike, meteor strike, auto-ignition or hot surface ignition, a fire migrating to the CWT from another fuel tank via the vent system, an uncontained engine failure, a turbine burst in the air conditioning packs beneath the CWT, a malfunctioning CWT jettison/override pump, a malfunctioning CWT scavenger pump, or static electricity.[1]:272–279 After analysis the investigation determined that these potential sources were "very unlikely" to have been the source of ignition.[1]:279

Fuel quantity indication system

[edit | edit source]Because a combustible fuel/air mixture will always exist in fuel tanks, Boeing designers had attempted to eliminate all possible sources of ignition in the 747's tanks. To do so, all devices are protected from vapor intrusion, and voltages and currents used by the Fuel Quantity Indication System (FQIS) are kept very low. In the case of the 747-100 series, the only wiring located inside the CWT is that which is associated with the FQIS.[citation needed]

In order for the FQIS to have been Flight 800's ignition source, a transfer of higher-than-normal voltage to the FQIS would have needed to occur, as well as some mechanism whereby the excess energy was released by the FQIS wiring into the CWT. While the NTSB determined that factors suggesting the likelihood of a short circuit event existed, they added that "neither the release mechanism nor the location of the ignition inside the CWT could be determined from the available evidence." Nonetheless, the NTSB concluded that "the ignition energy for the CWT explosion most likely entered the CWT through the FQIS wiring".[citation needed]

Though the FQIS itself was designed to prevent danger by minimizing voltages and currents, the innermost tube of Flight 800's FQIS compensator showed damage similar to that of the compensator tube identified as the ignition source for the surge tank fire that destroyed a 747 near Madrid in 1976.[1]:293–294 This was not considered proof of a source of ignition. Evidence of arcing was found in a wire bundle that included FQIS wiring connecting to the center wing tank.[1]:288 Arcing signs were also seen on two wires sharing a cable raceway with FQIS wiring at station 955.[1]:288

The captain's cockpit voice recorder channel showed two "dropouts" of background power harmonics in the second before the recording ended (with the separation of the nose).[1]:289 This might well be the signature of an arc on cockpit wiring adjacent to the FQIS wiring. The captain commented on the "crazy" readings of the number 4 engine fuel flow gauge about 2 1/2 minutes before the CVR recording ended.[1]:290 Finally, the Center Wing Tank fuel quantity gauge was recovered and indicated 640 pounds instead of the 300 pounds that had been loaded into that tank.[1]:290 Experiments showed that applying power to a wire leading to the fuel quantity gauge can cause the digital display to change by several hundred pounds before the circuit breaker trips. Thus the gauge anomaly could have been caused by a short to the FQIS wiring.[1]:290 The NTSB concluded that the most likely source of sufficient voltage to cause ignition was a short from damaged wiring, or within electrical components of the FQIS. As not all components and wiring were recovered, it was not possible to pinpoint the source of the necessary voltage.

Report conclusions

[edit | edit source]The NTSB investigation ended with the adoption of the board's final report on August 23, 2000. The Board determined that the probable cause of the TWA 800 accident was:[1]:308

[An] explosion of the center wing fuel tank (CWT), resulting from ignition of the flammable fuel/air mixture in the tank. The source of ignition energy for the explosion could not be determined with certainty, but, of the sources evaluated by the investigation, the most likely was a short circuit outside of the CWT that allowed excessive voltage to enter it through electrical wiring associated with the fuel quantity indication system.

In addition to the probable cause, the NTSB found the following contributing factors to the accident:[1]:308

- The design and certification concept that fuel tank explosions could be prevented solely by precluding all ignition sources.

- The certification of the Boeing 747 with heat sources located beneath the CWT with no means to reduce the heat transferred into the CWT or to render the fuel tank vapor non-combustible.

During the course of its investigation, and in its final report, the NTSB issued fifteen safety recommendations, mostly covering fuel tank and wiring-related issues.[1]:309–312 Among the recommendations was that significant consideration should be given to the development of modifications such as nitrogen-inerting systems for new airplane designs and, where feasible, for existing airplanes.[25]:6

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFinal Report - ↑ a b c d "Medical/Forensic Group Factual Report" (PDF). Docket No. SA-516, Exhibit 19A. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ↑ a b Leland, John (August 5, 1996). "Grieving At Ground Zero". Newsweek Magazine. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ↑ Swarns, Rachel L. (August 7, 1996). "For Crash Victims' Families, A Painful Return to Routine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/08/07/nyregion/for-crash-victims-families-a-painful-return-to-routine.html.

- ↑ Gray, Lisa (October 23, 1997). "After the Crash". Houston Press. Retrieved November 4, 2012. "The Ramada Inn at JFK was "Crash Central," the gathering place for the 230 victims' families as well as investigators, the TWA "go team," and the media."

- ↑ Adamson, April (September 4, 1998). "Victims Knew Jet Was In Trouble Airport Inn Becomes Heartbreak Hotel Again". Philadelphia Inquirer. http://articles.philly.com/1998-09-04/news/25757670_1_twa-flight-twa-disaster-family-members.

- ↑ Nissen, Beth (November 17, 2011). "Hotel Near JFK Airport is Familiar With Airline Tragedy". CNN. http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0111/17/smn.21.html.

- ↑ Chang, Ying; Lambiet, Jose; Jere, Hester (July 20, 1996). "A Heartbreak Hotel for Kin They wait, Weep at JFK Ramada". New York Daily News. http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/news/heartbreak-hotel-kin-wait-weep-jfk-ramada-article-1.731576.

- ↑ a b c Van Natter Jr., Don (July 25, 1996). "Navy Retrieves 2 'Black Boxes' From Sea Floor". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/07/25/nyregion/the-fate-of-flight-800-the-overview-navy-retrieves-2-black-boxes-from-sea-floor.html.

- ↑ a b c Purdy, Matthew (July 30, 1996). "Airliner Bombings Are Reviewed For Similarities to T.W.A. Crash". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/07/30/nyregion/fate-flight-800-overview-airliner-bombings-are-reviewed-for-similarities-twa.html.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Sexton, Joe (August 23, 1996). "Behind a Calm Facade, Chaos, Distrust, Valor". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/08/23/nyregion/behind-a-calm-facade-chaos-distrust-valor.html?scp=2&sq=twa%20800%20recovery%20victims&st=nyt.

- ↑ a b Thomas, Evan (August 5, 1996). "Riddle Of The Depths". Newsweek Magazine. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ↑ International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers: Analysis and Recommendations Regarding T.W.A. Flight 800 Template:Webarchive

- ↑ a b "Documents Pertaining to Witnesses 300-399" (PDF). Docket No. SA-516, Appendix E. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k "Witness Group Chairman's Factual Report" (PDF). Docket No. ?, Exhibit 4-A. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ↑ National Transportation Safety Board. "Documents Pertaining to Witnesses 1-99" (PDF). Docket No. SA-516, Appendix B. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ↑ Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCVR Report - ↑ "Flight Data Recorder Group Chairman's Factual Report" (PDF). Docket No. 5A-516, Exhibit No. 10A. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ van Natta Jr., Don (August 31, 1996). "More Traces Of Explosive In Flight 800". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/08/31/nyregion/more-traces-of-explosive-in-flight-800.html.

- ↑ "Source: Traces of 2nd explosive found in TWA debris". CNN. August 30, 1996. http://www.cnn.com/US/9608/30/twa.pm/index.html.

- ↑ "Metallurgy/Structures Group Chairman Factual Report Sequencing Study" (PDF). Docket No. 5A-516, Exhibit No. 18A. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ↑ "Fire in the sky" (PDF). System Failure Case Studies. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Metallurgy/Structures Group Chairman Factual Report Sequencing Study" (PDF). Docket No. 5A-516, Exhibit No. 18TWA800A. National Transportation Safety Board: 3–4. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ↑ a b c d Tauss, Randolph M. "Solving the Mystery of the "Missile Sightings"" (PDF). The Crash of TWA Flight 800. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ "National Transportation Safety Board Safety Recommendation" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 8, 2010. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/69/Figure25.PNG/210px-Figure25.PNG)

](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Figure27.PNG/204px-Figure27.PNG)

](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ee/Radar_45.PNG/190px-Radar_45.PNG)

](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/TWA_Flight_800_zones.png/120px-TWA_Flight_800_zones.png)

](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/21/Twa_800_fig_22b.PNG/120px-Twa_800_fig_22b.PNG)

](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Twa_800_fig_22c.PNG/120px-Twa_800_fig_22c.PNG)