Law of the Sea

Preliminary Remarks The official first edition of this chapter has been published by Routledge. It can be purchased as a printed book or downloaded. This Wikibook serves as an open access backup of the official version. It should be noted that some chapters have not yet been adapted to match the official version. For authoritative reading, we therefore refer you to the version published by Routledge. For each chapter, interactive exercises have been created which can be accessed on our website. Simply follow this link or scan the QR code to access the exercises. |  |

Author: Alex P Dela Cruz, Tamsin Paige

Required knowledge: Link

Learning objectives: Understanding XY.

This is where the text begins.[1] This template follows our style guide. Please take into account our guidelines for didactics. If you're wondering how to create text in Wikibooks, feel free to check out our guide on how to write in Wikibooks.

This is your advanced content. You can create this text box using our template "Advanced". How to do this is described here.

Example for to example topic: This is your example.

Just replace the content above and below with your content.

A. Introduction

[edit | edit source]Most practitioners of international law will be familiar with the law of the sea as the specialised field of law that governs how states share and divide the ocean and its resources. The significance of this law lies in its being an important legal argumentative resource for states and corporations seeking to enter into cooperative endeavours, as well as in asserting their own interests and authority in relation to the ocean. This chapter will proceed as follows. After this introduction, Part B offers a brief history of the law of the sea until its codification into the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ('Law of the Sea Convention', 'LOSC').[2] Part C gives an outline of the maritime zones as defined in the LOSC. Part D closes this chapter with some remarks on the contemporary challenges confronting the law of the sea.

B. History of the Law of the Sea

[edit | edit source]The law of the sea has been described as ‘a persistently important theme’ of international law ‘from the very beginning’,[3] (see Founding Myths) but remained uncodified as a treaty for many centuries. Prior to the Hague Conference for the Codification of International Law in 1930, the law of the sea referred to a collection of various customs that different nations observed in relation to the ocean. Some of these customs included different measurements for, as well as ways of measuring, the breadth of a belt of water known as the territorial sea, over which a coastal state was said to exercise sovereignty, and different ways of regulating the passage of foreign vessels in those waters. States practised these customs unilaterally, or without regard for the interests of other states. These customs became topics for debate at the 1930 Hague Conference. However, the Conference concluded without producing a law of the sea treaty due to disagreement on the question of the breadth of the territorial sea.

After World War II, the United Nations convened the first Conference on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS I’) in Geneva in 1958. Four separate Geneva law of the sea conventions were adopted at the end of UNCLOS I, namely: the Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone (‘CTS’); the Convention on the High Seas (‘CHS’); the Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seals (‘CFCLR’); and the Convention on the Continental Shelf (‘CCS’). In particular, the CTS formally codified the customary law that the sovereignty of a coastal state extended from its land territory to the territorial sea. But like the 1930 Hague Conference, the question of the breadth of the territorial sea remained unsettled. UNCLOS I also concluded with the adoption of an Optional Protocol of Signature Concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes (‘OPSD’), but many states refused to ratify it. Because the conventions were adopted separately, states were free to choose the treaties they wished to ratify. The result was that the Geneva conventions did not achieve high numbers of ratification.

A second UN Conference on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS II’) was soon convened in 1960 in order to address the questions of the breadth of the territorial sea and the settlement of disputes, which remained unresolved under the Geneva law of the sea conventions. Again, sharp disagreements among states over those questions meant that UNCLOS II did not produce any treaties.

By the late 1960s, a large number of states had gained independence from imperial rule. (see Decolonisation) These states were previously unable to send delegations to UNCLOS I and II and felt that many of the provisions of the Geneva conventions did not reflect their needs and issues. Many newly independent states sought greater control over fishery resources, mineral resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction, preservation of the marine environment, national security from threats coming from the ocean, and marine technology.[4] Another source of dissatisfaction with the Geneva conventions was the fact that the breadth of the territorial sea remained unsettled. On this point, many newly independent states sought a wider territorial sea, while former imperial powers wanted to keep the territorial sea as narrow as possible in order to preserve the vast geographical scope of international waters or the high seas. The newly independent states generally held a mistrust for international law developed by their former imperial powers.[5] These new states sought a new ocean regime that would address their specific interests.

The newly independent states garnered enough numbers in the UN General Assembly to establish a Sea-bed Committee in 1968. Originally, this Committee was meant to study the possibility of a regime for the exploration and exploitation of mineral resources of the seabed beyond national jurisdiction based on the notion of the ‘common heritage of mankind’. It later evolved into a preparatory body for the third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS III’) that ran for nearly a decade from 1973 to 1982 between Geneva, Caracas, and New York.

Both the newly independent states and the former imperial powers agreed that UNCLOS III should aim to produce a single and universally-ratified ocean treaty from which states would not be allowed to make reservations (see Reservations) or exceptions. Ratification would mean that states are signing up to the ocean treaty as a single package. Both groups of states recognised that the topics of the law of the sea formed an interrelated field in which compromises between competing interests were essential for the success of the then-future ocean treaty.[6] UNCLOS III divided its work into three main committees, dealing with the seabed regime, the law of the sea in general, and the marine environment and marine scientific research. Even then, delegates acknowledged that the work of one committee had important implications for the other two committees.[7] For example, the question on the breadth of the territorial sea was directly related to the question of where exactly ‘areas beyond national jurisdiction’ began. If a belt of water was ‘territorial sea’, then it fell under the sovereignty of a coastal state, while waters in areas beyond national jurisdiction might be subject to ‘common heritage of mankind’ principles or other less restrictive regimes. One of these areas beyond national jurisdiction was known simply under the general designation of 'The Area', which consists of the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.[2] The Area will be described in more detail in Part C.

Individual committees each produced informal single negotiating texts (‘ISNTs’) as their bases for discussion at the committee level. In 1977, these ISNTs were merged into a single ‘Informal Composite Negotiating Text’ (‘ICNT’). The ICNT was the first coordinated attempt to articulate the various parts of the law of the sea as a single coherent treaty text.[8] UNCLOS III adopted provisions through a combination of consensus and majority voting, with a view to preventing a few recalcitrant states from blocking an emerging consensus on a point of law.[9]

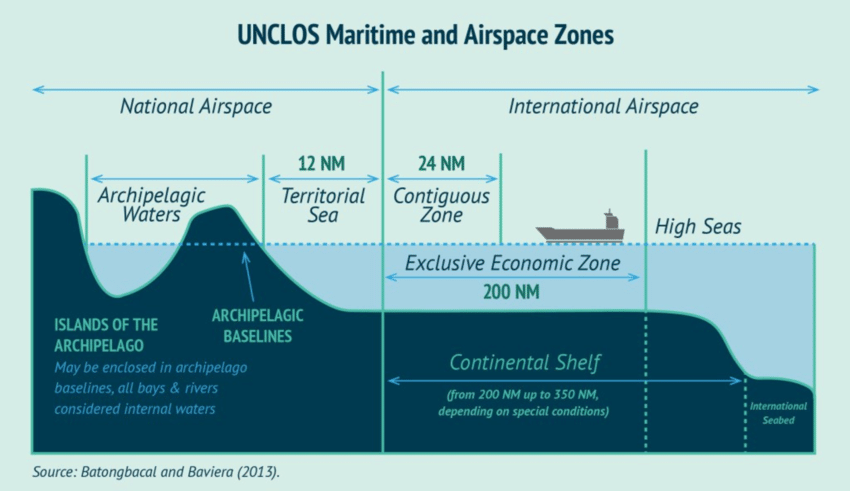

Efforts to reach consensus over the draft convention failed when the new Reagan administration in the United States ordered a thorough review of the draft convention in 1980. The US and other industrialised and maritime powers were specifically opposed to part of the draft convention that established a regime for the seabed beyond national jurisdiction, which meant that the draft convention had to be adopted by a vote. On 30 April 1982, the LOSC’[10] was adopted by 130 votes in favour, 4 against, and 17 abstentions. The Convention opened for signature in Montego Bay, Jamaica on 10 December 1982, but the standing objections of the industrialised maritime powers meant that the LOSC would not enter into force until twelve years later. The LOSC adopted a zonal approach to the ocean, dividing waters into maritime zones with specific dimensions. Some of these zones are (a) the territorial sea, 12 nautical miles from the low-water mark on the shore of the coastal state; (b)the contiguous zone, 24 nautical miles; and (c) the exclusive economic zone, 200 nautical miles. The LOSC also codified rules on innocent, transit, and archipelagic sea lanes passage, the latter two types of passage being the LOSC’s distinctive contribution to the language of international law.[11]

Between the Convention’s adoption in 1982 and its entry into force in 1994, the US, Britain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, West Germany, and Japan were in an arrangement called the Reciprocating States Regime (‘RSR’). The RSR refuted the universal application of the LOSC, particularly Part XI of the Convention that established the seabed beyond national jurisdiction as the common heritage of mankind.[12] It was the adoption of the 1994 Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (‘1994 Implementing Agreement’) which removed the objections of the RSR states. The salient feature of the 1994 Implementing Agreement is that it now allows multinational consortia controlled by the RSR states to apply for seabed exploration permits on the same terms applicable to LOSC pioneer investors from developing nations. The LOSC finally entered into force on 16 November 1994.

C. Maritime Zones

[edit | edit source]The LOSC is the omnibus treaty governing international law regulating ocean spaces. It has been ratified by 168 states (including Palestine in 2015, with Azerbaijan being the most recent in 2016),[13] and is considered to be a codification of customary international law. Even world powers who have not ratified the LOSC, such as the US, consider it to be customary in nature with the exception of Part XI of the Convention (concerning The Area).[14] For the most part, the LOSC sets out how states are entitled to use various parts of the ocean and jurisdictional regimes relating to different ocean regions. The LOSC was also responsible for a significant reduction in scope of the high seas (also known as international waters) around the world due to the expansion of the territorial sea and the creation of the exclusive economic zone and of archipelagic waters for certain island-and-water formations.

The different zones of jurisdiction that make up the core of the LOSC all start from the definition and premise of maritime baselines. Maritime baselines as a concept are simply the demarcation point between what is considered the landed territory of a state, and what is considered to be part of the ocean and thus governed by the LOSC. The starting point for determining baselines (and the rule that applies in most circumstances) is set out in Article 5, which states that “the normal baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea is the low-water line along the coast as marked on large-scale charts officially recognised by the Coastal State.”[15] This rule was relatively uncontroversial as a standard of geographical demarcation for most states. However, additional rules were developed in Article 6, Article 7, and Article 10 to account for non-standard coastlines, such as fringing reefs, coastlines with deep indentations or fringing islands, or small entirely enclosed bays. Article 6 sets out that the baseline can be drawn from the low water line of the reef;[16] Article 7 sets out the rules for drawing straight baselines to allow for ease of maritime zone measurement in situations where the coastline has deep indentations, or fringing islands;[17] and Article 10 sets out the rules for baselines enclosing bays.[18] Once the baselines of the state have been established in accordance with articles 7, 9, and 10, and the delimitation drawn in accordance with articles 12 and 15 the coastal state is required to publicly publish these charts and deposit a copy of them with the Secretary-General of the United Nations.[19] It is worth noting that it is generally accepted that baselines move as the coastline changes; however, with climate change causing significant sea level rise and reduction of coast, particularly for small island states, there is a strong argument on ground of equity for fixing baselines.[20] From these baselines the law of the sea divides maritime zones into three broad categories (each with specific subcategories): zones of sovereign control; zones with sovereign rights; and areas beyond national jurisdictions.

I. Sovereign Zones

[edit | edit source]

1. Internal Waters

[edit | edit source]After the baselines of the state have been established, Article 8(1) declares that all territory on the landward side of the baselines constitutes the internal waters of the coastal state (with particular exceptions set out in Part IV of the LOSC for archipelagic states). The coastal state exercises full territorial sovereignty over its internal waters,[21] with the primary difference between internal waters and the territorial sea being that internal waters are not subject to the various rights vessels possess when in the territorial sea (with the exception of historical freedom of navigation rights over areas that were not considered internal waters prior to the LOSC).[22] With the exception of some limits of jurisdiction over foreign flagged vessel set out in Article 27 and 28,[23] the internal waters of a state operate legally in the same manner as the states landed territory.

2. Territorial Sea

[edit | edit source]The territorial sea is the first maritime zone that exists beyond the baselines of a state. Historically, the territorial sea had been set to a limit of three nautical miles, with this limit being updated in the drafting of the LOSC to a maximum of 12 nautical miles. Much like the internal waters of a state, the territorial sea constitutes the full sovereign territory of the coastal state.[24] The primary distinction between the territorial sea and the internal waters is therefore the obligations that states owe to foreign flagged vessels within their territorial sea. The primary right that vessels of all states possess in the territorial sea is the right of innocent passage, guaranteed by Article 17.[25] The details of what constitutes innocent passage is set out in Articles 18 to 26 of the LOSC. Innocent passage is the right to transit in a “continuous and expeditious”[26] manner through the territorial sea in a way that is “not prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal State.”[27] This includes requiring submarines to travel surfaced with their flag displayed,[28] and for vessels operating under nuclear power to carry documentation making this known, and to follow any precautionary measures set out in international agreements.[29]

Example for controversy over the meaning of innocent passage: This last requirement has been a source of long-running contention between New Zealand and the United States – New Zealand prohibits any nuclear vessels from entering its territorial sea, and the US for reasons of military secrecy refuses to disclose which vessels in its navy operate under nuclear power.[30] As such, New Zealand has taken the position since 1984 that no US warships (or any other vessel operating under a nuclear power plant) are exercising innocent passage when entering the New Zealand territorial sea as any of them theoretically may be operating under nuclear power.

The other restrictions on coastal state sovereignty within the territorial sea (with these also applying to the internal waters of the state) are limitations on criminal and civil jurisdictions being exercised over foreign flagged vessels.[31] This is linked with LOSC Article 92, which grants exclusive jurisdiction to the flag state over vessels on the high seas.[32] Because the LOSC treats vessels as an extension of the territorial jurisdiction of the flag state, limitations on coastal state jurisdiction regarding both criminal and civil law exist. These limitations are set out respectively in LOSC Articles 27 and 28.

3. Straits

[edit | edit source]Part III of the LOSC does not specifically define a strait, but the term usually refers to a waterway bordered by one or more coastal states, which ships use for international navigation. States bordering straits used for international navigation (strait states) retain sovereignty or jurisdiction over such waters and their airspace, seabed and subsoil, subject to the regime of transit passage and other rules of international law.[33]

Transit passage is a regime of passage that is less restrictive than the traditional right of innocent passage in the territorial sea. This means that ships navigating through international straits are subject to lesser restrictions that they would normally be when passing through the territorial sea of a coastal state. Article 38(2) of the LOSC defines transit passage as the exercise of the freedom of navigation and overflight ‘solely for the purpose of continuous and expeditious transit of the strait between one part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone and another part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone’. ‘Continuous and expeditious transit’, however, does not prevent ships from using the strait in order to enter, leave, or return from one of the states bordering the strait.[34] A foreign ship using a strait for transit passage may not carry out marine scientific research, hydrographic surveys, or other research activities without prior authorisation from the states bordering the strait.[35]

Strait states are allowed to designate sea lanes and traffic separation schemes for navigation in order to promote safe passage of ships.[36] But before such designation, strait states are required to refer proposed sea lane designations and traffic separation schemes to a competent international organisation with a view to their adoption.[37] That competent international organisation is now generally understood to be the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), and the adoption procedure under Article 41 is intended to strictly circumscribe the powers of both strait states and the IMO in relation to sea lanes designation and traffic separation schemes.[38]

4. Archipelagic Waters

[edit | edit source]The term ‘archipelagic waters’ refers to a category of waters which form an element of the definition of an archipelago in Article 46(b) of the LOSC: ‘a group of islands, including parts of islands, interconnecting waters and other natural features which are so closely interrelated that such islands, waters and other natural features form an intrinsic geographical, economic and political entity, or which historically have been regarded as such’. Article 47 of the LOSC outlines the steps through which an archipelagic state might draw its archipelagic baselines joining the outermost points of the outermost islands and drying reefs of the archipelago. The waters encompassed within these baselines are archipelagic waters, except those waters that the archipelagic state might delimit as internal waters in accordance with Articles 9, 10, and 11.[39] Archipelagic waters are subject to the sovereignty of an archipelagic state, regardless of those waters’ depth or distance from the coast.[40]

Sovereignty over archipelagic waters, however, is subject to a few limitations. For example, an archipelagic state is under an obligation to respect existing agreements with other states and to recognise traditional fishing rights and other legitimate activities of immediately adjacent neighbouring states in archipelagic waters.[41] Archipelagic states are also required to respect existing submarine cables laid by other states and passing through archipelagic waters without making a landfall and permit the maintenance and replacement of those cables.[42]

Two regimes of passage apply to archipelagic waters. These are (1) innocent passage and (2) archipelagic sea lanes passage. Ships of all states enjoy the right of innocent passage in archipelagic waters as they would in the territorial sea of a coastal state, subject to the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage and without prejudice to the right of the archipelagic state to delimit internal waters within its archipelagic waters.[43] An archipelagic state may temporarily suspend innocent passage in archipelagic waters without discrimination among foreign ships when essential for the protection of its security.[44]

The right of archipelagic sea lanes passage evolved from the right of transit passage through international straits. Like strait states, archipelagic states may designate sea lanes and air routes for the ‘continuous and expeditious passage of foreign ships and aircraft through or over its archipelagic waters and the adjacent territorial sea’.[45] But while Article 52(1) of the LOSC guarantees the right of innocent passage through archipelagic waters to ‘ships of all States’, Article 53(2) simply states that ‘All ships and aircraft enjoy the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage’ in such sea lanes and air routes as the archipelagic state may designate. Similar to the designation of sea lanes and traffic separation in international straits, an archipelagic state’s designation and substitution of sea lanes and traffic separation schemes in archipelagic waters also require approval from the IMO.[46] An archipelagic state that chooses not to designate sea lanes and air routes is deemed to have consented to the enjoyment by all ships and aircraft of the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage in all routes within archipelagic waters that are normally used for international navigation.[47]

II. Sovereign Rights

[edit | edit source]1. Contiguous Zone

[edit | edit source]The contiguous zone is the first of three zones that constitute areas beyond national jurisdiction where coastal states retain some sovereign rights over the territory. Article 33 sets out the limits of those rights for the contiguous zone. It specifies that the contiguous zone can extend no more than 24 nautical miles from the state’s baselines (so 12 nautical miles from the edge of the territorial sea).[48] Within the contiguous zone the state possesses the right to prevent infringement of “customs, for school, immigration or sanitary laws” within its territory.[49] This right does not allow for an exercise of domestic law over these issues, rather, the state possesses the right to prevent entry to the territorial sea (by declaring passage by the vessel to not be innocent) where the vessel in question would be violating the law should it enter. Within the contiguous zone the coastal state may also exercise a domestic criminal jurisdiction where violations of the law have already been committed within its territory.[50]

2. Exclusive Economic Zone

[edit | edit source]The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), created in Part V of the LOSC, establishes exactly what is promised in the name – a zone within the oceans of exclusive economic rights for the coastal state. The EEZ regime allows coastal states to establish an area of no greater than 200 nautical miles from the baseline where they gain:

[S]overeign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or nonliving, of the waters super adjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from water currents and winds.[51]

In addition to this, the coastal state also gains the jurisdiction over the years regarding marine scientific research, the establishment and use of artificial islands and other structures within the zone, and the protection and preservation of the marine environment. Article 73 also grants the coastal state with rights of law enforcement related to these sovereign rights within the EEZ.[52] Where the resourcing of the EEZ are situated in two or more EEZs and/or the high seas, the LOSC requires that these resources be managed through regional or subregional mechanisms (for example see the Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks Agreement and varied regional fisheries management organisations ('RFMOs')).[53] Where the EEZ of coastal states would overlap, or neighbouring coastal states can’t agree on the delimitation line, Article 74 requires an equitable solution, with options for dispute settlement procedures provided in Part XV of UNCLOS if an agreement cannot be reached (numerous ICJ cases have addressed such disputes).[54] Outside of these specific economic rights the EEZ functions in the same manner as the high seas.[55]

3. Continental Shelf

[edit | edit source]Part VI of the LOSC sets out the rights of states over the continental shelf. The continental shelf is the area of the ocean floor seabed and subsoil. Under ordinary circumstances, the continental shelf of the state, much like the EEZ, is limited to a maximum of 200 nautical miles from the baselines of the state; however, Article 76 provides grounds under which states can claim an extended continental shelf.[56] Annex II of the LOSC establishes the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf ('CLCS') to assist with the application of the dense rules contained within Article 76.[57] The continental shelf itself grants similar sovereign rights to the coastal state that the EEZ does, except over the resources contained within the seabed rather than within the ocean.[58] The other primary difference between the continental shelf and the EEZ is that while the EEZ needs to be claimed, the continental shelf is considered an inherent right of the coastal state as an extension of the landed territorial.[59]

III. Beyond National Jurisdiction

[edit | edit source]1. The High Seas

[edit | edit source]The high seas covers all of the areas of the oceans beyond the zones detailed above (and the EEZ for noneconomic purposes), with it being clear that any claims of sovereignty will be considered invalid over this zone. Article 87 sets out the freedoms that are enjoyed by all states and vessels when on the high seas. These include: freedom of navigation and overflight;[60] freedom to lay submarine cables and pipelines (subject to continental shelf restrictions);[61] freedom to construct artificial islands and other installations (subject to international law in particular continental shelf restrictions);[62] freedom of fishing (subject to due regard for the interests of other states, and regulations set out in the Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks Agreement or by regional fisheries management agencies);[63] and freedom of scientific research (subject to continental shelf restrictions and Part XIII of UNCLOS).[64] With these freedoms established at the beginning of Part VII of the LOSC, the rest of the sections addressing the high seas focus upon the jurisdiction of states over vessels within this maritime zone.

Article 92 of the LOSC sets out that the jurisdiction over a vessel shall belong exclusively to the state whose flag is being flown.[65] Flag states have duties, including but not limited to: maintaining a register of ships flying its flying, ensuring the seaworthiness of vessels, ensuring that vessels have all the appropriate equipment for safety of navigation, assuming jurisdiction of its domestic law over the vessel, ensuring adequate crewing and labour standards on the vessel and that all crew have appropriate qualifications.[66] This also includes the assumption of criminal jurisdiction over incidences of navigation caused by vessels flying their flag.[67] The high seas section of the LOSC also sets out the various grounds of jurisdiction in which government or warships may engage in various activities such as the prevention of piracy, suppression of slave trafficking, and un-authorised radio broadcasting.[68] It also contains the obligation of all vessels to render assistance to those in distress within their vicinity.[69] Part VII of the LOSC also sets out that warships and government vessels on non-commercial service have immunity from the jurisdiction of any state other than the flag state.[70]

2. The Area

[edit | edit source]The area is to the high seas as the continental shelf is to the EEZ. It is the subsoil and seabed in the areas beyond national jurisdiction,[71] and is addressed in Part XI and a separate implementing agreement related to Part XI. Part XI sets up the area as part of the common heritage of all humankind,[72] requiring that any exploitation of resources contained within the area to be used for the betterment and benefit of all peoples.[73] With this in mind the LOSC also set up the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to govern the activities being undertaken within this zone.[74] As noted above this approach was controversial and led to great power states declining to ratify the LOSC out of the objections that they wouldn’t be able to engage in disproportionate exploitation of any resources found within the zone. To date no commercial exploitation of resources contained within the Area has been deemed viable.

D. Contemprary Challenges

[edit | edit source]UNCLOS III concluded in the adoption of a Convention that was very much a product of the time of its making. Conference delegates sought to maintain a reasonable balance between the interests of coastal states and those of the international community. But almost as soon as the LOSC entered into force, the ‘territorial temptation’ of individual states for greater sovereignty over the ocean has threatened to undermine the common interest side of the balance.[75] The urge to greater sovereignty over the ocean in various guises poses challenges to the application of the LOSC in four key areas: (1) environment and biodiversity; and (2) state sponsorship of activities in the deep seabed; (3) islands and sea level rise; and (4) maritime disputes.

I. Environment and biodiversity

[edit | edit source]Part XII of the LOSC deals with the protection of the marine environment. Specifically, Article 237 maintains the ability of states to enter into further agreements relating to the protection and preservation of the marine environment, provided that these agreements are ‘concluded in furtherance of the general principles and objectives of this Convention’. This provision enables states to address marine environmental concerns at a regional level. Regional agreements under Article 237 have been described as a ‘significant source of further development of the law of the sea’.[76]

The proliferation of regional agreements may undermine the near-universal consensus achieved in the LOSC. Boyle argues that ‘fragmentation is an inherent risk in any system of law built on the consent of States’.[77] Yet he also writes that there has been no real basis to suggest that regional cooperation has critically weakened the LOSC; the opposite is actually true. In the context of the South China Sea, for example, the lack of a specific regional seas convention (‘RSC’) has meant that the implementation of LOSC Part XII relies heavily on the benevolence or goodwill of South China Sea littoral states. This non-committal and evasive arrangement among the littoral states exposes the South China Sea to the risk of serious and long-term marine environmental damage.[78]

In 2017, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 72/249 in order to elaborate the text of another international legally binding instrument under the LOSC on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (‘BBNJ’).[79] The BBNJ agenda includes marine genetic resources, marine protected areas, environmental impact assessment, and capacity building and transfer of technology. Work towards this agenda is currently being done through an Intergovernmental Conference, whose proceedings have been stalled by the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been predicted that the work of the Intergovernmental Conference will have to contend with conceptual difficulty in the relationship between a new legally binding instrument that existing law of the sea agreements, including the LOSC, will ‘fundamentally restrict the scope of application’ of a future BBNJ instrument.[80]

II. State sponsorship of activities in the deep seabed

[edit | edit source]Article 153 of the LOSC provides that one of the ways in which activities for the exploration and exploitation of the deep seabed beyond national jurisdiction (which the LOSC refers to as the ‘Area’) may be carried out is when such activities are ‘sponsored’ by states-parties to the LOSC in accordance with the rules, regulations, and procedures of the International Seabed Authority (‘ISA’). ‘Sponsorship’ refers to the framework created by the LOSC through which a State Party exercises ‘control’ over contractors with respect to activities in the Area ‘by requiring [contractors] to comply with the provisions of [the Convention].’[81]

Example for state sponsorhsip: Nauru is currently one of four Pacific island states which use the power of sponsorship in order to generate revenue. In 2015, Nauru passed legislation requiring contractors to pay a sponsorship application fee of US$ 15,000, an annual administration fee of US$ 20,000, and ‘Seabed Mineral recovery payments’ based on a percentage of the still undetermined ‘market value of the metal content contained in the Seabed Minerals to be extracted by the Sponsored Party through the Seabed Mineral Activities.’ But as the ISA is expected to collect royalties under a forthcoming Mining Code and prospective sponsoring states scramble to attract seabed mining contractors, it is unlikely that Nauru would be able to collect substantive payments from sponsorship under the Convention.[82] The case of Nauru suggests that the attempt at UNCLOS III to produce legal arrangements such as sponsorship which are responsive to the economic needs of newly independent states is not likely to achieve that avowed goal.

III. Islands and sea level rise

[edit | edit source]Article 121(1) of the LOSC defines an island as 'a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide'. Under Article 121(2), islands generate an entitlement to the full suite of maritime zones in the LOSC ie, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the EEZ, and the continental shelf. As the worsening effects of the ongoing climate crisis melt polar ice caps, islands are expected to bear significant impacts from rising sea levels. While large areas of continental landmasses and islands could potentially submerge underwater as a result of sea level rise, small islands and their populations are particularly vulnerable. One possible legal scenario is that the submergence of land areas could lead to an interpretation that an island would also lose entitlement to maritime zones. LOSC Article 121(3) seems to lend support to such an interpretation in favour of loss of maritime entitlement.[83] That provision states that islands which are 'rocks' that 'cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf'.

In August 2021, the member-states of the Pacific Islands Forum published the Declaration on Preserving Maritime Zones in the Face of Climate Change-Related Sea Level Rise ('Declaration on Sea Level Rise').[84] In it, the PIF declared that the LOSC 'imposes no affirmative obligation to keep baselines and outer limits of maritime zones under review nor to update charts or lists of geographical coordinates once deposited with the Secretary-General of the United Nations'. The Declaration also records the official PIF position that 'maintaining maritime zones established in accordance with the Convention, and rights and entitlements that flow from them, notwithstanding climate change-related sea level rise, is supported by both the Convention and the legal principles underpinning it'. But whether maritime entitlements should be preserved or contract as a consequence of sea level rise remains 'very much an open issue'.[85]

IV. Maritime Disputes

[edit | edit source]The LOSC continues to play an important role in informing the ways in which states assert their claims to the ocean. For example, in relation to the South China Sea, maritime policymakers look to the LOSC as an important source of arguments for clarifying their claims over disputed waters.[86] And yet, as Laksamana notes, where policymakers are not confident about their maritime claims based on their reading of the LOSC, states have had to seek what he describes as 'tension management pathways' that may serve as a precursor to 'good faith' negotiations on maritime delimitation in the future.[87] But whether and the extent to which these tension management pathways should be consistent with the LOSC remains to be seen.

Further Readings

[edit | edit source]- Source I

- Source II

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]- Summary I

- Summary II

Footnotes

[edit source]- ↑ The first footnote. Please adhere to OSCOLA when formating citations. Whenever possible, provide a link with the citation, ideally to an open-access source.

- ↑ a b "LOSC art 1(1)". United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ↑ RY Jennings, ‘A Changing International Law of the Sea’ [1972] 31 Cambridge LJ 32.

- ↑ Christopher W Pinto, ‘Problems of Developing States and Their Effects on Decisions on Law of the Sea’ in Lewis M Alexander (ed), The Law of the Sea: Needs and Interests of Developing Countries: Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Conference of the Law of the Sea Institute, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, Rhode Island, June 26–29, 1972 (University of Rhode Island, 1973) 3–13.

- ↑ Tullio Treves, ‘Law of the Sea’, Max Planck Encyclopedias of International Law (April 2011) [c] <https://opil.ouplaw.com/view/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e1186?rskey=5Zfnbf&result=15&prd=MPIL> (accessed 12 April 2022).

- ↑ James Harrison, Making the Law of the Sea: A Study in the Development of International Law (Cambridge UP, 2011) 44.

- ↑ Paul Bamela Engo, ‘Issues of the First Committee’ in Albert W Koers and Bernard H Oxman (eds), The 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea (University of Hawaii Law of the Sea Institute, 1984) 40.

- ↑ Jens Evensen, ‘Keynote Address’ in Albert W Koers and Bernard H Oxman (eds), The 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea (University of Hawaii Law of the Sea Institute, 1984) xxvi.

- ↑ Daniel Vignes, ‘Will the Third Conference on the Law of the Sea work according to consensus rule?’ [1975] 69 AJIL 119, 120.

- ↑ United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (1833 UNTS 3) Art 5 (‘Law of the Sea Convention’, ‘LOSC’).

- ↑ Arthur Ralph Carnegie, ‘Environmental Law Challenges to the Law of the Sea Convention: Progressive Development of Progressive Development’ in Hans Corell et al (eds), International Law as a Language for International Relations (United Nations, 1996) 551.

- ↑ Surabhi Ranganathan, Strategically Created Treaty Conflicts and the Politics of International Law (Cambridge UP, 2014) 151.

- ↑ ‘United Nations Treaty Collection’ <https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetailsIII.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXI-6&chapter=21&Temp=mtdsg3&clang=_en> accessed 11 April 2022.

- ↑ See for example: Joint Statement by the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 1989.

- ↑ United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (1833 UNTS 3) Art 5.

- ↑ ibid Art 6.

- ↑ ibid Art 7.

- ↑ ibid Art 10.

- ↑ bid Art 16.

- ↑ Tim Stephen, ‘Warming Waters and Souring Seas: Climate Change and Ocean Acidification’ in Donald Rothwell and others (eds), The Oxford handbook of the law of the sea (First edition, Oxford University Press 2015) 790–793.

- ↑ UNCLOS Art 2(1).

- ↑ ibid Art. 8(2).

- ↑ ibid Arts 27 and 28.

- ↑ ibid Art 2.

- ↑ ibid Art 17.

- ↑ ibid Art 18(2).

- ↑ ibid Art 19(2).

- ↑ ibid Art 20.

- ↑ ibid Art 23.

- ↑ Henry Cronic, ‘New Zealand’s Anti-Nuclear Legislation and the United States in 1985 | Wilson Center’ <https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/new-zealands-anti-nuclear-legislation-and-united-states-1985> accessed 11 April 2022.

- ↑ UNCLOS Arts 27 and 28.

- ↑ ibid Art 92.

- ↑ ibid Art 34.

- ↑ ibid Art 38(2).

- ↑ ibid Art 40.

- ↑ ibid Art 41(1).

- ↑ ibid Art 41(4).

- ↑ James Harrison, Making the Law of the Sea: A Study in the Development of International Law (Cambridge UP, 2011) 181.

- ↑ UNCLOS Art 50.

- ↑ ibid Art 49(1).

- ↑ ibid Art 51(1).

- ↑ ibid Art 51(2).

- ↑ ibid Art 52(1).

- ↑ ibid Art 52(2).

- ↑ ibid Art 53(1).

- ↑ ibid Art 53(9).

- ↑ ibid Art 53(12).

- ↑ UNCLOS Art 33(2).

- ↑ ibid Art 33. mer

- ↑ bid Art 33(1)(b).

- ↑ ibid Art 56(1)(a).

- ↑ ibid Art 73.

- ↑ ibid Arts 63 and 64. Examples of RFMOs include the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources ('CCAMLR'), the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation ('SPRFMO'), and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission ('WCPFC'). Some RFMOs have a focus on specific species of marine life, such as the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, and the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation.

- ↑ ibid Art 74(2).

- ↑ ibid Art 58.

- ↑ ibid Art 76.

- ↑ ibid Annex II.

- ↑ ibid Art 77.

- ↑ North Sea Continental Shelf (Federal Republic of Germany v Denmark; Federal Republic of Germany v Netherlands) [1969] ICJ Reports 3 (International Court of Justice) [43].

- ↑ UNCLOS Art 87(1)(a) and (b).

- ↑ ibid Art 87(1)(c).

- ↑ ibid Art 87(1)(c).

- ↑ ibid Art 87(1)(e).

- ↑ ibid Art 87(1)(f).

- ↑ ibid Art 92.

- ↑ ibid Art 94.

- ↑ [1] ibid Art 97.

- ↑ ibid Arts 100-107, 99, and 109 respectively.

- ↑ ibid Art 98.

- ↑ ibid Arts 95 and 96.

- ↑ ibid Art 1(1).

- ↑ ibid Art 136.

- ↑ ibid Art 140.

- ↑ ibid Art 156.

- ↑ Bernard H Oxman, ‘The Territorial Temptation: A Siren Song at Sea’ [2006] 100 AJIL 830–51.

- ↑ Alan Boyle, ‘Further Development of the Law of the Sea Convention: Mechanisms for Change’ [2005] 54 ICLQ 563, 575.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Alexis Ian P Dela Cruz, ‘A South China Sea Regional Seas Convention: Transcending Soft Law and State Goodwill in Marine Environmental Governance?’ [2019] 6 J Territorial and Maritime S 5, 23.

- ↑ International legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction, GA Res 72/249, UN Doc A/RES/72/249 (24 December 2017).

- ↑ Hwang Junshik, ‘Challenges on the Ocean and the Future Law of the Sea: Environment, Security and Human Right’ [2016] 3 J Territorial and Maritime S 53, 59.

- ↑ Ximena Hinrichs Oyarce, ‘Sponsoring States in the Area: Obligations, Liability and the Role of Developing States’ [2018] 95 Marine Policy 317.

- ↑ Feichtner (n 50) 631.

- ↑ Purcell, Kate (2019). Geographical Change and the Law of the Sea. p. 231. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198743644.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-874364-4.

- ↑ "Declaration on Preserving Maritime Zones in the Face of Climate Change-related Sea-Level Rise – Forum Sec". Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ↑ Freestone, David; Cicek, Duygu (2021-06-29). Legal Dimensions of Sea Level Rise: Pacific Perspectives. World Bank. p. 35. doi:10.1596/35881.

- ↑ "Not all maritime disputes are built the same | Lowy Institute". www.lowyinstitute.org. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ↑ ibid.