Mentor teacher/Print version/theories about mentoring

Theories about mentoring

[edit | edit source]Origins

[edit | edit source]There is a consensus that the action-reflection model has been the most influential mentoring model in Norway. The model has been developing since the 1980s with Handal and Lauvås (1983, 1990) as originators. The model became the guide for a whole generation of Norwegian mentors (Skagen 2004:31) through the national plan for counselling studies in Norwegian university colleges. Of particular note is the model's influence on early childhood educators starting in the early 1990s (Carson and Birkeland 2009).

The model was developed during a time when mentors were facing criticism for taking too much control over the student teachers' practicum. It was assumed that the student teachers had to follow the mentor's wishes, since the final certification of teacher candidates was ultimately the mentor's decision. As a result, some were of the opinion that the teacher education primarily produced dependent teachers (Skagen 2004:31). The action-reflection model was hence developed as a counterbalance to a hierarchical tradition of apprenticeship, which was central in the Norwegian teacher education through to until the late 1980s. This apprenticeship model emphasized the master's work as an example to be imitated (Carson and Birkleland (2009: 68). Characteristics

"Practice theory" is an important term in the action-reflection model. It can be defined as the values, experiences and knowledge that determine the person's actions or plan of action. “Practice theory” refers to every person's subjective notion of practice and preparedness for practice. With the term, Lauvås and Handal (2000) assume that every person has a personal, cognitive action strategy which builds on knowledge and experience with other people. These strategies and ideas are arranged according to values that we consider relevant. For most people the practice theory is rather cluttered, random and filled with discrepancies.

The focus of the mentoring is on helping the mentee become better at understanding her own practice theory. The mentoring focuses on the theory behind the practice. The goal is to create awareness about core values that direct our actions. The mentee can achieve an increased understanding of these core values when asked to justify and explain her own actions. A greater awareness of what the theory consists of makes it possible to expand the mentee's repertory of actions. Since the core values in practice theory are often contradictory, it is essential to create self-awareness in the mentee.

Questions such as what we stand for as professionals or what the values are behind our actions, can contribute to strengthening our professional identity. Carson and Birkeland (2009:72-73) describe practice theory as follows:

- "Practice theory" is individual because every person possesses different knowledge, experiences and values.

- "Practice theory" is ever-changing because we continue to make new experiences. This may lead to a change in values, even though values have a tendency to be more resistant to change than knowledge.

- Everyone has a "practice theory", even those who are new to professional life.

- "Practice theory" is largely unconscious and difficult to formulate. People are often unaware of the values that guide their actions.

- "Practice theory" is often incoherent, and the values can be in opposition to each other.

In the action-reflection model, the focus is on planned, formalized mentor-mentee conferences, as opposed to the apprenticeship model, where the focus is rather on informal mentoring in the ongoing daily interaction. The mentoring is based on the mentee's expressed needs, and the mentee is usually asked to develop a mentorship plan for practicum. This is a document that will help both mentor and mentee prepare the mentoring.

Originally the model was geared towards the mentoring of student teachers regarding topics related to teaching. Today, the model is also used in the mentoring of experienced teachers, and the mentoring varies depending on how long the teacher has been teaching. Newly certified teachers, for instance, might need mentoring to acquire a clearer professional identity. More experienced professionals might use mentoring to avoid stagnation and burn out (Carson and Birkeland 2009:72-75).

Theoretical sources of inspiration

[edit | edit source]Handal and Lauvås describe the action-reflection model as humanistic and dialectic. Amongst the authors that inspired them was Ole B. Thomsen. Thomsen argued that student teachers should be joint participants in developing the criteria for good teaching. They were also influenced by Carl Rogers' ideas of self-realization and personal growth (Skagen 2004: 32). Donald Schön's emphasis on the teacher's capability to reflect over her own actions is yet another inspiration for the model.

Criticism

[edit | edit source]The action-reflection model has been criticized for several reasons. Firstly, some believe that the model serves to weaken the mentor's professional authority because of the focus on dialogue.Secondly, some question whether there is too much emphasis on individual differences and preferences, and not enough emphasis on the ability to adapt to the specific mentoring tasks. Thirdly, some suggest that the theoretical basis for the model is unclear. By emphasizing reflection, we might lose the focus on proper actions. The model will also favour students with good verbal skills (Skagen 2004: 124). Søndenå (2004:16) finds it problematic that all practical theories are considered equal. In our eagerness to develop the mentee's ability to reflect, we might forget what should be the purpose of our reflection.

References

[edit | edit source]- Carson, Nina og Åsta Birkeland (2009). Veiledning for førskolelærere. Kristiansand: Høgskoleforlaget

- Handal, Gunnar og Per Lauvås (1983). På egne vilkår: en strategi for veiledning med lærere. Oslo: Cappelen. Revidert utgave fra 1999 er tilgjengelig i full versjon.

- Handal, Gunnar og Per Lauvås (1990). Veiledning og praktisk yrkesteori. Oslo: Cappelen. Hele boken elektronisk

- Skagen, Kaare (2004) I veiledningens landskap. Kristiansand: Høgskoleforlaget.

- Søndenå, Kari (2004). Kraftfull refleksjon i lærerutdanningen. Oslo: Abstrakt forlag.

What is the apprenticeship model?

[edit | edit source]

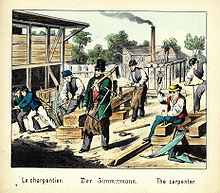

Historically, there was hardly any formal training of craftsmen. The training took place under the watch of experienced craftsmen in working communities where the apprentice received continuous mentoring. The master demonstrated the correct way of completing a task, and afterwards the apprentice attempted to imitate the master's skills, while being corrected for any mistakes.

This traditional model of apprenticeship originated in the European guilds of the Middle Ages. The guilds appeared in the 12th century. Before training began, the apprentice and the master craftsman would sign a legal contract, with specific terms for the training. The apprentice was required to sign an apprenticeship contract of several years before he/she could become a journeyman, a person fully trained in a trade or craft, but not yet a master craftsman (Skagen 2004:118). The Encyclopedia Britannica (2013 online edition) defines apprenticeship as: “training in an art, trade, or craft under a legal agreement that defines the duration and conditions of the relationship between master and apprentice”.[1]

The term “apprenticeship” can be used in two ways. The first to describe the statutory institutional structures that have dominated vocational education. The second is as a general metaphor for a relationship where a novice learns from an experienced person. The master knows how the work should be done. He/She models the work for the novice, who in turn tries to follow the master's example. The last decade has seen a rebirth of the apprenticeship model, and many now consider the master-apprentice relation to be a good vocational learning model. The apprenticeship model has also been introduced outside of the traditional vocational education, as a general pedagogical model (Nielsen and Kvale 1999).

Usage

[edit | edit source]The apprenticeship model has a particularly strong foothold within vocational pedagogy (Skagen 2004: 118). As a metaphor, it refers to an asymmetrical relationship between two individuals, one who has mastered the skills of the trade (the master), and another who has not (the apprentice). Similar to a traditional teacher-student relationship, this model is based on one-way communication. During the process, the apprentice acquires tacit knowledge through observing the master as he/she uses her skills (Polanyi 1958). This perspective can also be used to analyze the interplay between parent and child. Through the participation in daily activities, children learn skills by observing their parents (Rogoff 1990). This kind of learning is sometimes described as observational learning (see Albert Bandura).

Characteristics

[edit | edit source]Nielsen and Kvale (1999:19) mention four characteristics of the apprenticeship model as a pedagogical idea:

- Participation in a community of practice: The apprenticeship takes place in a social organization, for instance a community of craftsmen. The apprentice learns by participating in a group of competent practitioners of a craft. The novice advances from “peripheral legitimate participation” to “full participation”, and gradually becomes a more competent member of the professional culture. Mentoring is done all the time in these communities, but it is not considered a separate activity. Reflection and action take place side by side. Mentoring does not follow a universal formula, but is adapted to the specific situation.

- Professional identity: The apprentice learns by completing practical assignments that gradually become more difficult. The professional identity is developed through the process of mastering new skills. The reflective conversation should take place soon after the assignment, or it may not have the desired effect.

- Learning through imitation of the master: The novice observes and imitates the work of the master or other skilled workers in a community. The mentoring process follows a traditional pattern, starting with the master demonstrating the correct execution of an assignment. The apprentice then starts to practice, and is corrected by the master until he/she is proficient at the skill. The master will often give more in the beginning of the process,and gradually less.

- The quality of the work is evaluated through practice: The quality of a product is judged on its functionality and the customers' feedback. The master governs the accumulated knowledge of the particular craft, and has developed subtle and complex criteria for the evaluation of craftsmanship. These criteria, however, are often characterized by tacit knowledge and are therefore not articulated. It´s therefore the master who selects the assignment which are appropriate for the apprentice.

The apprenticeship model is based on the assumption that competence can not be acquired through verbal communication alone. Competence is partly situational and improvisational. It can therefore be challenging for the master to find the balance between demonstrating how to complete an assignment and explaining it with words. Visualization, demonstration, observation and imitation are principal techniques.

Important theories

[edit | edit source]

The theory of situated learning is central within the apprenticeship model (Lave and Wenger 1991). The focus is not on cognitive processes (see for instance cognitive learning theory), but on learning through interactions between individuals, cultural tools and social communities. Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger (1991) developed this theory by studying how craftsmen in African societies learn. Learning takes place by participating in a community of practice, which is “formed by people who engage in a process of collective learning in a shared domain of human endeavour”.[2] In the community of practice, the apprentice is initially seen as a “legitimate peripheral participant”. The learning trajectory depends on the possibilities that are given to the individual in the community of learning (Nielsen and Kvale 1999).

With their focus on the community of practice, Lave and Wenger (1991) downplay the pedagogical importance of the master as an individual. The apprentice also learns a great deal from other apprentices and from trial and error. This approach is contradictory to Hubert and Stuart Dreyfus, who focus on how a novice learns from the master in a one-to-one relationship by observing and imitation. The novice does not necessarily need to be part of a larger social environment. This form of learning happens within both sports and research.

In the literature on communities of practice, the term scaffolding is used to describe how the instruction is adapted to the needs of the apprentice. Scaffolding means that the master offers support, and creates interest in the work for instance by simplifying practical assignments, explaining targets or evaluating the quality of the work produced by the apprentice. The master must also try at balance the apprentice's frustration on one side and willingness to take risks on the other side (inspiration: Rogoff). The term scaffolding is similar to the term zone of proximal development, originally developed by Lev Vygotsky. The idea behind the zone of proximal development is that the novice can only learn new skills in a tailored situation, and with support from a more capable person. The teacher might be thinking out loud while solving mathematical problems, and giving the student an opportunity to develop strategies and problem solving. Observational learning is another important learning method, where the learner imitates a model's novel behaviour through observation [3]. This theory was originally introduced by Albert Bandura.

The importance of the apprenticeship model in many professions

[edit | edit source]

Language often plays a subordinate role in the training of craftsmen, particularly during observation and demonstration. Most importantly, mentoring and practical work take place side by side. For instance, experienced architects mentor their students at the drawing board. Students are learning how to draw, while they are simultaneously discussing reasons behind their choices. According to Skagen (2004:19), Donald Schön rejects the notion that this form of apprenticeship simply means copying someone else's actions. He argues that the novice instead uses these experiences to develop her own work style. Schön uses the terms reflective imitation, imitative reconstruction and selective reconstruction to describe these processes. The idea is that the students must enter into a relation of dependence, before being able to become independent. To illustrate, Skagen (2004) cites two personal narratives from one of Schön's books, describing how architects mentor their students:

Personal narrative no. 1: Johanna's mentor has a strong opinion about how an architect should draw. While some of the students are intimidated by the mentor because of this, Johanna is not. She believes that she will learn a great deal by following the mentor's ideas, and decides to participate on these premises. She does not worry that she will become dependent on the mentor, but rather thinks that she can develop her own style later. Before being able to do that, however, she must understand how the mentor works. To her this is a paradox. She lets the mentor take control over the course of learning, but to her the goal is to later gain greater control over her own project. It is Johanna's reflective ability and courage that makes it possible for her to let go of some of her own opinions for the time being (Skagen 2004: 121-122, citing Schön, 1988:121-126).

Personal narrative no. 2: Another architecture student, Judith, has more issues with the same mentor. She has a strong opinion about what architecture is, and how an architect should work. She spends a lot of energy defending her own ideas when the mentor makes suggestions. She experiences the mentor's suggestions as an attack on herself as a professional person. Because she is not capable of being self-critical towards her own professional understanding, she is also not capable of listening to the mentor's suggestions. Neither is she interested in the mentor's comments, but wants praise for the work she does when she does her own way. The result is that she is not capable of integrating advices from the mentor with her own understanding. Judith is not capable of taking the cognitive risk which is needed to start her own learning journey (Skagen 2004:122, citing Schön, 1988: 126-137).

Criticism of the apprenticeship model

[edit | edit source]Some critics claim that the apprenticeship model has nothing to do with mentoring. Within the teacher education in Norway, for instance, mentoring courses have traditionally focused on the action-reflection model. The action-reflection model came as a reaction to the tradition of apprenticeship. According to critics the traditional apprenticeship model, dominant at that time, did little but cultivate “parrot teachers”. It has now become legitimate to include the apprenticeship model as one of several mentoring approaches in introductory books about mentoring pedagogy (Skagen 2004 and Løv 2009). This approach, however, emphasizes the importance of giving advice more than other mentoring approaches.

It is worth noting that some theories within the apprenticeship model also focus on group mentoring (i.e. the community of practice approach) in contrast to traditional mentoring approaches which usually focus on individual mentoring (i.e. the action-reflection model). In addition informal mentoring is more important within the apprenticeship model compared with the action-reflection model, which emphasizes formalized mentor-mentee conversations. Learning is considerd as the most important type of learning, while the action-reflection model maintains that the mentee should put thoughts into words. The critique against the apprenticeship model can be summarized in the following way:

- The apprenticeship model has been criticized because it requires one correct solution to the assignment. The approach might also sustain traditional practice and inhibit creativity and innovation. Supporters of the apprenticeship model, on the other hand, claim that learning by observation is necessary in order to being able to develop creativity later.

- The apprenticeship model requires a close connection between reflection and the professional practice. Verbalization is not essential and the result might be less in-depth reflection.

- The apprenticeship model downplays the mentee's right to formulate requests and criteria for own growth. Instead it is the vocational traditions which govern the mentoring practice. The mentoring approach criticizes progressive education which focus too much on creativity, self-development and learner autonomy.

- The fact that the master must be competent within a craft or a profession, limitates who can act as a mentor. Within the action-reflection model, it is more important that the mentor has communicative competence, that is the ability to develop good relations and ask good questions. Knowledge about the professional knowledge is not considered as equally important.

- The apprenticeship model has been criticized for valuing practice higher than theory. Excessive concern with mastering professional skills can undermine time used to learn important theoretical principles (Skagen 2004: 122-123).

Integration of the apprenticeship model in teacher education

[edit | edit source]In recent decades there has been a lot of focus on fostering reflective teachers in teacher education (Skagen 2004: 121). The didactic model of Hiim and Hippe[4], for instance, builds on this idea. Skagen (2004: 125-126) criticizes this mentoring approach as being one-sided. The reflective conversation is dominant. Nowadays, the new teacher following initiation into the teaching profession is quickly provided full responsibilities for teaching with little opportunity to observe other teachers. Within the apprenticeship model, one could alternatively picture a situation where the student teacher is responsible for part of the teaching, until the final certification. When that is said, there is little empirical research to show which mentoring models are in fact used in the practicum of the teacher education.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/30748/apprenticeship

- ↑ http://www.ewenger.com/theory/

- ↑ http://psychcentral.com/encyclopedia/2009/observational-learning

- ↑ http://www.learning-at-distance.eu/docs/pedagogical/PT6_didactic.pdf

Sources

[edit | edit source]- Hiim, Hilde og Else Hippe (2006) Undervisningsplanlegging for yrkesfaglærere. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk forlag.

- Lave, Jean og Etienne Wenger (1991). Situated learning : legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

- Nielsen Klaus og Steinar Kvale (1999). Mesterlære: læring som sosial praksis. Oslo: Ad Notam Gyldendal.

- Polanyi, Michael (1958). Personal knowledge. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Rogoff, Barbara (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: cognitive development in social context. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Skagen, Kaare (2004). I veiledningens landskap. Kristiansand: Høgskoleforlaget.

Video resources

[edit | edit source]- Lecture by Jean Lave (2012) about apprenticeship and learning.

Characteristics

[edit | edit source]Systemic mentoring is a mentoring approach designed to create awareness in the mentee of how people influence on and are influenced by their environment. The mentoring approach is based on ideas proposed by Gregory Bateson and Urie Bronfenbrenner, among others. A person is always considered as part of a social system and interpersonal relationships (Skagen 2004;89-90). Central concepts in the systems theory are wholeness, human relations and circularity.

The term “wholeness” refers is used to emphasize that phenomenons are connected to each other. As a consequence people will always influence each other mutually in human relations. For instance, in an educational institution there will be relations between mentors, between school management and the mentor, and between mentor and mentee. Even though not all these parties participate directly in the mentoring, but they can all influence how the mentoring is organized. Additionally, on the organizational level there are relations between institutions involved in mentoring (cf. Bronfenbrenner). Thus, when the mentee tries to solve a problem, this may also involves parties which are directly involved in mentoring (Skagen 2004:90).

In daily interaction we have a tendency to evaluate our actions according to the existence of a cause and an effect. The result of this thinking is that we might not look at all relevant perspective (Skagen 2004:90). In systemic mentoring exclusive why-questions are viewed as unproductive as they imply the existence of one cause and one effect (i.e. “Why did you do that?”). In contrast systemic mentoring uses a more circular explanation model where all parties always will contribute to the interaction. When we explain an interaction we first punctuate the interaction. When we punctuate, we end the process of interaction, and start interpreting the interaction. We explain the reasons behind what is happening between the parties. “The teacher is yelling because the students are loud” could also be interpreted as “The students are loud because the teacher is yelling”. The term “punctuation” refers to the concept that there are always alternative ways to understand an incident. If we punctuate the interaction differently, we will have a different understanding of the interaction (Carson and Birkeland 2009: 92-94).

Question techniques in systemic mentoring

[edit | edit source]Within systemic mentoring, the assumption is that the mentee is incapable of finding a solution to a difficult situation. In order to stimulate change it´s possible to use circular questions developed by the Milan group (link?) (Carson and Birkeland 2009:102-103). The types of questions are divided into four categories. To illustrate we start by giving an example:

The pedagogical leader wants mentoring related to this case. In the following section we present different types of questions which is common to use within this mentoring approach.

Questions that explore differences

[edit | edit source]These questions are divided into four subcategories:

Questions that explore differences on a personal level

[edit | edit source]These questions are based on the assumption that we all react differently to a situation. The intention is to increase the awareness of how people react differently in a situation. From the story in example 1 the mentor can ask the following questions within this mentoring approach:

- Who was present?

- How did the other children react to Bente's behavior?

- How did the other assistant react to Bente's behavior?

The questions will raise the mentee´s awareness of the different reactions from the people present, and may in this way lead to a better understanding of the incident.

Questions that explore differences on a relational level

[edit | edit source]These questions explore differences in interpersonal relations. The mentee is asked to describe different relationships, and explain how they are different. Questions can be:

- How is the relationship between Bente and Per?

- between Bente and the other children?

- between you and Bente?

- between Bente and the other assistant?

- Who is closest to Bente?

- How is your relation to Bente different from your relation to the other assistant?

These questions could reveal more differences in the relationships. They raise awareness around the relations Bente is a part of.

Questions that explore differences in opinions, ideas, values and motives

[edit | edit source]These questions focus on how we imagine other people perceive the situation. The aim is to stimulate us to think differently around the situation. We can ask questions such as:

- What do you think Bente was thinking when she reacted the way she did?

- What do you think the other assistant was thinking when she noticed Bente's behavior?

- How is your way of handling a similar situation different from Bente's approach?

- How did Bente explain her reaction?

These questions are intended to elicit thoughts regarding how the situation is understood, and experienced in different ways by the persons involved. This includes differences in values and in the perception of children.

Questions that explore differences between the present and the future

[edit | edit source]With these questions we consider the ways that different people react to new situations. The focus is on the involved parties' reaction in previous situations, and how they might have reacted differently. Compared to the previous example, a question might be:

- Has Bente previously reacted to Per in a similar manner?

All these questions can give the mentee a wider and more complex picture of an experienced situation.

Questions that explore behavioural effect

[edit | edit source]These questions try to make the mentee more aware of the mutual influence people have on each other. They focus on how the mentee experienced other people´s behavior and how we experienced other people's behavior. The ability to understand the other person's perspective is essential to empathy. When discussing the same case, we could ask the following question:

- How do you think Bente experienced what you did?

Triadic questions

[edit | edit source]The purpose of triadic questions is to create awareness of the third party's experience of the interaction. We can ask questions such as:

- How do you think the children perceive the relationship between you and the assistants?

- How do you think Per, the other children and the other assistant experienced your intervention?

These question also attempt to create awareness of the reciprocal relationship between people. The mentor should help the mentee to develop an ability to observe herself from the outside (Carson and Birkeland 2009: 105).

Hypothetical questions

[edit | edit source]By asking questions about different future scenarios, the mentee is encourage to reflect around alternative options. Possible questions are:

- How would you feel if Bente was to leave?

- If you were to make changes in your relationship with Bente, what would they be?

- What is required for you and the assistant to reach an agreement?

- If you were successful in making changes, what would the situation be like?

- What is hampering such a change? (Carson and Birkeland 2009: 105)

Such hypothetical questions may help the mentee to look for an alternative course of action. It´s also important to be stimulated to reflect upon how the situation might look if the problem was solved.

Example – To se oneself from the outside

[edit | edit source]Berit is supervisor in a daycare and manager of a group of employees that consists of two assistants, a learning support teacher and a special needs educator. Below are two personal narratives she has written and for which she received systemic mentoring (from Carson and Birkeland 2009: 107-110).

The mentorship conversation

Before the mentorship conversation (Personal narrative nr.1)

"I need help with my relationship to the learning support teacher. She is taking charge over us in our daily work and is even taking charge of the parents. Her only responsibility is a child with special needs. At our staff meeting we almost always quarrel about who should make decisions. The more I take charge, the more dominant she becomes. I feel very frustrated because I am the pedagogcial leader and she should acknowledge that."

In the mentorship conversation the mentor chooses to use circular questions based on systemic mentoring, such as: “How do you think the others see you as pedagogical leader?” Berit will then become more aware of her own role in the interaction. She is forced to become her own observer. A question regarding the future such as: “how do you wish the relationship should be?” makes her aware of things she has not yet considered. When you are stuck in a destructive communication pattern, it is easy to forget to think constructively and creatively.

After the mentorship conversation (Personal narrative nr.2)

"Now I am glad! I understand my own role and how I was trapped. When I was asked how other persons experienced the situation, I realized that I believed there was an alliance between the special needs teacher and the learning support teacher. I regarded this alliance as a threat to me as a leader. When the mentor asked me how I think they experience me, I also realized that they must perceive me as a an incompetent leader. Thus, I have to admit that this is how I see myself. This has been difficult to acknowledge. When the mentor asked how I wanted the relationship between myself and the learning support teacher to be, I discovered that I had not thought about it. I had been more concerned about how I did not want it to be. This is something I need to work on. I need to take more responsibility for my role as a pedagogical leader."

The first personal narrative indicates that Berit seems to be stuck in a destructive interaction pattern. The usual assumption is that it is the other person who is the problem and needs to change. It can be difficult to see how we can make a difference ourselves. In the second narrative Berit has developed a clearer understanding of her own responsibilities as a pedagogical leader.

Sources

[edit | edit source]- Baltzersen, Rolf K. (2008). Å samtale om samtalen. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Bomar, Perri J. (2003), Promoting Health in Families: Applying Family Research and Theory in Nursing

- Carson, Nina og Åsta Birkeland (2009). Veiledning for førskolelærere. Kristiansand: Høgskoleforlaget

- Gjems, Liv (1995) Veiledning i profesjonsgrupper. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. Hele boken

- Skagen, Kaare (2004) I veiledningens landskap. Kristiansand: Høgskoleforlaget.

- Ulleberg, Inger (2004). Kommunikasjon og veiledning : en innføring i Gregory Batesons kommunikasjonsteori - med historier fra veiledningspraksis. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

What is Appreciative Inquiry?

[edit | edit source]Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is a mentoring approach that seeks to identify and foster the best in people and organizations. “Appreciative” refers to the attempt at focusing on things we appreciate and that create value. “Inquiry” refers to the search for what is already working and has value. AI has received increased attention in recent years (Cooperrider & Srivastva 1087; Cooperrider & Srivastva 1999; Cooperrider & Whitney 2000).

When undertaking an appreciative inquiry, we start by examining aspects of the person's life and work she finds meaningful and productive. This approach is done on the assumption that people will achieve transformative goals quicker by strengthening their pre-existing resources. A situation may also be strengthened by the alternative method of problem analysis, but problem analysis may also worsen a situation (Cooperrider & Srivastva 1987). According to Cooperrider & Srivastva (1987), appreciative inquiry builds on the following assumptions:

- All organizations and all individuals have success stories to show that can contribute to positive development.

- All development is based on experience. And when we start the process with positive experiences, the road to development becomes more meaningful. We should make positive experiences visible and active in the organization.

- Inquiry and change stand in a dialectic relationship to each other. By starting an inquiry, we simultaneously start a change process.

When making these changes, employees will understand what is important in the organization, what creates a good life, happiness, development and freedom (Ludema, Cooperrider & Barrett 2006). People who are recognized for their strengths and qualities are willing to give more. In order to understand what is working, it is necessary to reflect on the characteristics of good experiences and achievements. The theoretical base for the approach is based on the following assumptions:

- Importance, meaning and recognition are created through interaction with others.

- Language as a tool can be used to construct a positive reality.

- What we see as reality is not created inside us, but between individuals through language.

The four phases of Appreciative Inquiry

[edit | edit source]An appreciative inquiry is done in four phases (Cooperrider & Srivastva 1999; Cooperrider & Whitney 2000; Ludema, Cooperrider & Barrett 2006; Whitney & Trosten-Blom 2003). This is also referred to as the 4-D cycle: Discovery, Dream, Design and Destiny.

1. Discovery The purpose of the discovery phase is to identify situations where an organization or an individual's performance is at its best. The discovery is done through systematic charting, for instance by qualitative data collection methods such as interviews. Common for this data collection is the search for positive stories. The idea is that by telling stories, we reveal how we perceive and experience our lives. And by bringing these stories forward, and with them our experiences, we will be able to create a common experience base around what we value and what energizes us in our daily lives. During interviews, the following positively formed questions could be posed:

- What makes us happy?

- What contributes to making us happy?

- What helps us bring forward the positive?

When listening to employees during this process, we try to identify and explore energizing aspects of their stories. The key is to uncover energizing stories and understand the areas that give vitality to individuals and organizations.

2. Dream After charting valuable experiences, we formulate dreams and visions for the future. We exchange notions of a preferred future. For an appreciative inquiry to work, it must be based on participation. Ideally, it should involve all employees in an organization or a team, and as far as possible also collaborators and users.

3. Design In the design phase employees make precise descriptions of how the organization's day to day practice would look once the dream or vision has been fulfilled. They formulate precise goals and create an action plan for the way ahead. In this phase the organization's employees make an attempt at creating relations and systems that can support the desired development. The purpose of this phase is to define a vision and what is needed to realize this vision.

4. Destiny In the destiny phase the employees adopt initiatives in order to realize the goals that were developed in the design phase. This requires a specific action plan describing what needs to be done when and by whom. The employees reinforce positive experiences from the past and attempt new measures. The learning process continues with adjustments and experimentation. More benefits in this phase are realized based on the amount of effective and creative tools for evaluation and development that have been identified.

Use and examples

[edit | edit source]Appreciative inquiry can be used:

- to reflect on competences and resources in a group of employees.

- to create knowledge of and reflect on professional work.

- to determine the priorities management and employees will use for day-to-day work.

- to plan and implement organizational development.

(Cooperrider & Srivastva 1999; Cooperrider & Whitney 2000; Ludema, Cooperrider & Barrett 2006; Whitney & Trosten-Blom 2003).

Sources

[edit | edit source]- Cooperrider, D.L. and Srivastva, S. (1987). Appreciative Inquiry in Organizational Life, Research in Organizational Change and Development, 1, pp. 129-169. Original article (read 15.06.12)

- Cooperrider, D. L., & Srivastva, S. (1999). Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In: S. Srivastva & D. L. Cooperrider (Eds), Appreciative Management and Leadership: The Power of Positive Thought and Action in Organization (Rev. ed., pp. 401–441). Cleveland, OH: Lakeshore Communications.

- Cooperrider, D.L. & Whitney, D. (2000). A Positive Revolution in Change: Appreciative Inquiry. Appreciative Inquiry Commons. Original article

- Ludema, J.D., Cooperrider, D.L., & Barrett, F.J. (2006). Appreciative Inquiry: the Power of the Unconditional Positive Question. I Reason, Peter & Bradbury, Hilary (Eds.) (2006). Handbook of Action Research. Sage. London

- Whitney, D. & Trosten-Blom, A. (2003). The Power of Appreciative Inquiry. A Practical Guide to Positive Change. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers

- http://appreciativeinquiry.case.edu/uploads/Introduction%20to%20Appreciative%20Inquiry.pdf

Relevant internet resources

[edit | edit source]- Appreciative Inquiry Commons (http://appreciativeinquiry.case.edu) has articles and commentaries on Appreciative Inquiry in theory and practice, as well as information on workshops and conferences.

- The Taos Institute (http://www.taosinstitute.net/)

- Anne Radford (http://www.aradford.co.uk/) is editor of AI Practitioner and has other AI resources.

What is coaching?

[edit | edit source]The term coaching originates from the word “coach”, a medium of transport. In 19th century England the word “coach” came to be used to describe a private teacher who assisted students preparing for exams. The transposition of a word for transport to a name for a teacher came about for these 19th century exam preparation teachers due to the students' conception that they were being driven through the examinations or were able to ride through the examinations on a coach with the help of their prep teachers. In some recent conceptions of mentoring, the word “coach” is used metaphorically as the guide who assists the mentee on her inner journey. The coach assists the mentee to improve her own abilities, by developing mental or practical skills (Skagen 2004).

Origins

[edit | edit source]

Coaching as a form of mentoring was originally developed in American sports. The Norwegian football coach Knut Rockne was a pioneer in developing the sports coach as mentor concept. It was, however, tennis coach Timothy Gallwey who popularized the coach as mentor guiding the mentee on an inner journey model. Gallwey claimed that the key to becoming a good tennis player, is to master what he calls the “inner game”. His book “The Inner Game of Tennis” became an inspiration for several names in coaching, i.e. Myles Downey and John Whitmore.

Gallwey alleged that relaxed concentration is essential to mastering the game of tennis. The player must not criticize or judge his own achievements. Paradoxically, the secret to winning a game is not trying too hard. The player must concentrate on the game and not on winning. To enable the release of energy and resources and maximization of the performance it is imperative to enter into a state of serenity. This state does not need to be learned, as it is part of us, but we may have acquired bad habits that prevent us from entering it. To reach this productive state we should not analyze our actions, but rather create images of ourselves performing good actions. We must stop judging our own shortcomings in a negative way. This requires us to separate between an observation of our actions on one side, and an evaluation of this observation on the other. This optimal state, as described by Gallwey, has similarities with Csikszentmihalyi's notion of flow (Skagen 2004). Coaching as mentoring has later been introduced in executive coaching, business coaching and life coaching. Additionally, several other types of coaching have emerged. The term is today more often than not used as a reflective and conversational method whereby one person assists another to realize the maximum potential of their abilities in a particular area (Skagen 2004).

Source

[edit | edit source]- Skagen, Kaare (2004) I veiledningens landskap. Kristiansand: Høgskoleforlaget.

Different stages of skill acquisition

[edit | edit source]Hubert L. and Stuart E. Dreyfus refer to various studies of learning processes and claim that a person acquires skills by passing through different stages. They base their theory on empirical studies and observations of sensory-motor skills such as biking, swimming, aircraft piloting, and cognitive skills such as chess-playing. In the book “Mind Over Machine” (1986), they describe a stage model of skill acquisition:

| Stage | Characteristics | Teacher |

|---|---|---|

| Expert | The difference between the expert and the proficient performer is that the expert is immediately and intuitively capable of making the right decision, or seeing the right strategy or action to take. The action is based on a holistic evaluation of the situation. | An expert teacher often has a broad experience from various schools and is quickly capable of understanding all aspects of a situation. |

| Proficient | The proficient performer instantly sees the connection between earlier experiences and new situations. The reaction is immediate and intuitive. There is a correlation between intuition and analysis. Discretionary judgment and interpretation is more important than in the competent performer. | |

| Competent | The competent performer is capable of making choices and priorities in a situation, based on work experience. Some use of interpretation and discretion. The basis of experience is broader than that of the advanced beginner. | |

| Advanced beginner | The advanced beginner has more practical experience than the novice. Recognizes important dimensions and circumstances in a situation. | A student teacher who is an advanced beginner (following a completed education), has experience from numerous lessons and different classes. |

| Novice | A novice learns through demonstration and instruction. She learns that it is important to focus on particular rules, facts and traits in a situation. The novice's learning situation is protected from “real life”. | During the first practicum lesson, advice given by the mentor will determine the student teacher's approach to teaching. |

Hubert L. and Stuart E. Dreyfus argue that once an individual has acquired a skill, she can act without following rules, consciously or unconsciously. Neither is it necessary that she understands the purpose of the action. It is her body that reacts to the demands of the situation. In this, Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1999) are influenced by the philosopher Merleau-Ponty. According to Merleau-Ponty, “when one's situation deviates from some optimal body-environment relationship, one's activity takes one closer to that optimum and thereby relieves the "tension" of the deviation. One does not need to know, nor can one normally express, what that optimum is. One's body is simply solicited by the situation to get into equilibrium with it” (Dreyfus 1998).

Examples

[edit | edit source]One example is how a skilled soccer player immediately understands when and how to dribble around the opponent (Tiller 2006). There is no indication that such a skilled soccer player has time to consider rules before dribbling. When Maradona dribbled around the entire English defence during the 1986 World Cup, he had not planned this in advance. Based on the situation, Maradona made a quick assessment whether to pass the ball or to continue dribbling. Maradona's expertise can be linked to what is known as tacit knowledge. This implies that the knowledge is non-explicit; it can not always be communicated to others as rules or distinct recommendations. A masterful driver is “one” with her car, and a masterful teacher is “one” with her classroom. Compared to research done on rational decision making processes, little research has been done on intuitive decision making processes.

How to become an expert?

[edit | edit source]Towards the end of an online video presentation, Dreyfus stresses that in order to reach the expert stage, we need to take chances (as opposed to following routines). We do not become experts without making, and learning from, serious mistakes.

Sources

[edit | edit source]- Dreyfus, Hubert L., Dreyfus, Stuart E. og Tom Athanasiou (1986). Mind over machine : the power of human intuition and expertise in the era of the computer. New York: Free Press

- Tiller, Tom (2006). Aksjonslæring - forskende partnerskap i skolen : motoren i det nye læringsløftet. Kristiansand: Høgskoleforlaget

- Bakke, Kari Renate & Emil Severin Tønnesen (2007) Lave & Wenger og Dreyfus & Dreyfus. Master thesis. Oslo: University of Oslo http://www.duo.uio.no/sok/work.html?WORKID=62030

- http://www.class.uh.edu/cogsci/dreyfus.html