Issues in Interdisciplinarity 2019-20/Printable version

| This is the print version of Issues in Interdisciplinarity 2019-20 You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Issues_in_Interdisciplinarity_2019-20

History of the Nuclear Family in Britain

This chapter will tackle the debate around the emergence of the nuclear family in Britain, within and between disciplines. The nuclear family is the basic type of family, composed of a conjugal pair and their children.[1] To understand the current debates surrounding the changing nature of the family and the reasons for the apparent decline of the nuclear family, studying its emergence is crucial.

Historical Context

[edit | edit source]The History of the Family only formed after 1958.[2] Initial research assigned the emergence of the nuclear family to the "structural modernisation of western societies since the 19th century".[2] The pre-nuclear family was seen as more complex in structure, changing due to nuclearization, individualism, and emotionalism.[2] From the 1970s, research became more defined, accounting the shift in family structures to a point earlier in History.[2]

Stone's 1977 research locates the late Medieval family, already concentrated around the nuclear family, within a complex system of kinship relations.[3] The family structure began forming more defined boundaries between 1500–1700, resulting in the isolated nuclear family between 1600–1700. The transformation was due to the diminishing importance of kinship and clientage, the increasing state power, and the missionary success of Protestantism.[3]

Macfarlarne (1987) provides a contradicting view,[2] arguing against a change in the structure of the English family in the early modern period, and that the family's key features were not caused by urbanisation, but actually "made such a development possible".[2]

While it is important to recognise that both change and continuity were present in the history of family,[2] this debate within history adds further complexity to taking an interdisciplinary approach.

Anthropological Approach

[edit | edit source]The term "nuclear family" first emerged within Anthropology during the 1940s.[1] Anthropology, however, distinguishes that the common focus on the nuclear family as a modern institution is not justified. In the late Roman Empire, the nuclear family already existed as the smallest unit of society.[4] There have even been discoveries of the graves of nuclear families dating back to 2600 BCE, such as the one by Haak et al found in 2006 in a late Neolithic community in Germany.[5][6]

Malinowski and other functionalists viewed the nuclear family as a "universal human institution"[7][8] and ascribed nurturing as its prime function. Later Anthropologists disagreed, identifying 'The Family' as a construct linked to the state's ideology and arguing that it is the mother-child relation that serves the function of child nurturing.[7] However, a conjugal pair has always been the centre of kin relations and served as "the basis of a nuclear family".[4]

Goody points out how the language around kinship highlights the crucial role of the nuclear family in England: While Anglo-Saxon words for nuclear family members and kin members were closely related, this changed after the conquest of England in 1066. The Norman-French terms for kin members were adapted, while Germanic roots of the closest kind remained. This merge of languages isolated the nuclear family within society.[4]

Anthropologists consider an earlier time period than other disciplines, often ignoring the possibility of later origins.

Sociology approach

[edit | edit source]Research on the nuclear family developed significantly from the early 1900s, with major shifts during the 20th century.[9] Sociologists have always fixated on a linear progression from extended families pre-industrialisation to the nuclear family post-industrialisation. Thus, focusing on Contemporary History in their analysis of the nuclear family has meant that they failed to consider factors pre-industrialisation.

Earlier sociologists, such as Parson[11] championed this theory. They believed industrialisation of Britain caused a complete transformation in family structure; a reduction in size, and prioritising of conjugal bonds rather than extended family.[9] Furthermore, it was thought that urbanisation, loosened kinship ties. The nuclear family was perceived as more suited to the higher demands of an industrial society due to their increased social and geographical mobility.[12] The popular theories of functionalism and modernism during the 1950s, formed a hierarchy of societies based on the progression towards nuclear families, which were seen as superior[13]

Revisionist Theory (1960s-1970s)

[edit | edit source]Revisionists[14] challenged importance of industrialisation in the formation of the nuclear family. Anderson explains how huge changes in production were only possible after or simultaneous to changing family order.[9] The use of more historical sources and a new emphasis on class in Sociology, helped create a more complex theory of the origins of the nuclear family.[9] Gordon[11] highlighted how working class families extended to deal with the hardships of industrialisation, showing that earlier theories were oversimplified. Ultimately both revisionists and traditional sociologists were limited by their fixation on the industrialisation and didn't appreciate the influence of other events before and after it.

Economic Approach

[edit | edit source]Pre-Industrial Revolution Beliefs

[edit | edit source]

Within Economics, there is little research into the origination of the nuclear family before the Industrial Revolution. Economists such as Alfred Marshall and Adam Smith, however, outlined the presence of neolocal residences[16], which form the foundations of a nuclear family.

19th Century Origins

[edit | edit source]As outlined in the Sociological Approach, Parsons' theory draws upon the economic impact of the Industrial Revolution on families. Parsons' lack of empirical evidence,[17] however, makes this theory weak from an economic perspective. Anderson's research also opposes this as he found 23% of households contained extended family[18] in an 1851 census, at the peak of industrialisation.

21st Century Research

[edit | edit source]Recent research into the History of the Nuclear Family focuses more on the shift in family structure, especially the transition into the 'typical' Nuclear Family seen in the 21st Century of a couple with two children. This shift is most apparent between 1881 and 1928 when the mean number of children within a family fell from 5.27 to 2.08.[19]

The main catalysts of the shift to a smaller family structure originated during World War I. With 40-60% of recruits failing health checks during the Boer War,[20] it became clear that social reform was necessary to have a strong labour force. The Liberal Government placed the pressure of financing these reforms on the wealthy through tax policies. Many families saw a break down of their wealth and a deterioration of the man's position within the home, paired with the increase in a women's independence during and after WWI, the typical roles within a family changed. Many landowners sold parts of their estates to compensate their loss of income, and these properties were largely partitioned into smaller units to help defeat the housing crisis. The combination of these factors led to a fall in the size of the family as a focus on children and wellbeing also began to dominate families' thinking.

Overall Economic research mostly investigates the shifts in family structures and their significance within society as opposed to its origins, thus it is less significant to the debate.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Anthropology differs in its temporal approach to the other disciplines. Economy, History, and especially Sociology tend to use historical dichotomies of before and after,[9] regarding the transformation from extended to nuclear families, disregarding periods of history that could be evaluated into analysis.

These disciplines have all evolved their arguments about the emergence of the nuclear family, especially over the last century. Whilst there are conflicts within disciplines, and more importantly between the disciplines about the emergence, an interdisciplinary approach allows a broader analysis of the topic, and a multi-faceted understanding of the implications of family structure in the ever-changing world around us.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b Murdock G. Social structure. George Peter Murdock, .. New York: Macmillan C°; 1949.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Wrightson K. The family in early modern England: continuity and change. In: Hanoverian Britain and Empire, Woodbridge: The Boydell Press; 1998

- ↑ a b Stone L. The family, sex and marriage in England 1500–1800. London: Penguin; 1990.

- ↑ a b c Goody J. The European Family. An Historico-Anthropological Essay. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd; 2000

- ↑ Haak W et al. Ancient DNA, Strontium isotopes, and osteological analyses shed light on social and kinship organization of the Later Stone Age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008; 105(47): 18226-18231. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0807592105

- ↑ Fortunato, L. Reconstructing the History of Marriage Strategies in Indio-European Speaking Societies: Monogamy and Polygamy. Human Biology. 2011; 83 (1): 87–105. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41466896?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

- ↑ a b Collier J, Rosaldo M, Yanagisako S. Is There a Family? New Anthropological Views. In: Thorne B, Yalom M. editors, Rethinking the Family: Some Feminist Questions. Boston: Northeastern University Press; 1992. Chapter 2.

- ↑ Malinowski B. The Family among the Australian Aborigines. London: University of London Press; 1913.

- ↑ a b c d e Anderson M. Sociology of the family. New York: Penguin; 1982.

- ↑ Industrial Revolution | Definition, Facts, & Summary [Internet]. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2019 [cited 8 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/event/Industrial-Revolution

- ↑ a b Gillies V. Family and Intimate Relationships: A Review of the Sociological Research [Families & Social Capital ESRC Research Group]. Southbank university; 2019.

- ↑ Livesey C. [Internet]. Sociology.org.uk. 2019 [cited 6 December 2019]. Available from: http://www.sociology.org.uk/notes/famfit.pdf

- ↑ Cherlin A. Goode's World Revolution and Family Patterns: A Reconsideration at Fifty Years. Population and Development Review [Internet]. 2012 [cited 6 December 2019];38(4):577-607. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41811930.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A86a6afcf4e9936bb8d50726c89df0b41

- ↑ Smith D. The Curious History of Theorizing about the History of the Western Nuclear Family. 2019.

- ↑ Sharma R. Adam Smith: The Father of Economics. Investopedia, Investopedia, 2019 Nov 18. Available from: www.investopedia.com/updates/adam-smith-economics/.

- ↑ Smith D. The Curious History of Theorizing about the History of the Western Nuclear Family. Social Science History. 1993;17(3)

- ↑ Abbott D. The Family and Industrialisation. Tutor2U. 2009. Available from: www.tutor2u.net/sociology/blog/the-family-and-industrialisation.

- ↑ Anderson M. Sociological History and the Working-Class Family: Smelser Revisited. Social History. 1976;1(3)

- ↑ Gente M. The Expansion of the Nuclear Family Unit in Great Britain between 1910 and 1920. The History of the Family. 2001;6(1). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1081602X0100063X

- ↑ Winter J. Military Fitness and Civilian Health in Britain during the First World War. Journal of Contemporary History. 1980;15(2): 211.

The issue of History in the 2013 - 2016 EVD epidemic

Introduction

[edit | edit source]The first outbreaks of the Ebola Virus Disease were in 1976 in the DRC and Sudan. The subsequent West African Epidemic reached mortality rates of up to 90%, more specifically in Liberia, Guinea, Mali, Sierra Leon, Nigeria and Senegal.[1] The epidemic had devastating social, political impacts on the countries’ economies and healthcare systems.

The death toll by October 2015, 11,323, begs us to question methods employed to end the outbreak.[2] Medical and biological sciences are needed to explain the origin and treatment of diseases, while understanding the cultural practices that prevented the containment of EVD requires anthropological perspectives. However, the history of these different disciplines is problematic in tackling the crisis, as scientific procedure tends to take precedence. We will therefore explore different disciplinary approaches to the 2013-2016 Ebola crisis, illustrating the benefits of interdisciplinary thinking.

Biology and Virology

[edit | edit source]Zaire Ebolavirus is one of the most virulent pathogens within the hemorrhagic fevers.[3] The virus spreads through contact with bodily fluids. The incubation period is 21 days, during which the patient may inadvertently cause propagation. Symptoms are similar to other diseases found in West Africa such as malaria, Lassa fever and typhoid, resulting in frequent misdiagnosis.

Its genome consists of non-segmented, negative-sense, and single-stranded RNA molecule. After contagion, the virus targets and weakens the immune system, specifically dendritic cells. In a study published by 'Cell Host & Microbe', research found that the VP24 protein on Ebola inhibits the production of antibodies.[4] Toxins trigger the release of proinflammatory cytokine and nitric oxide, which damage the endothelial lining of blood vessels. Then, the repeated coagulation reduces blood supply resulting in fatal organ failure.[5]

No cure exists for EVD, but in 2016 the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine was found to be 70-100% effective.[6]

Responses

[edit | edit source]1. Medical

[edit | edit source]The primary aim of medical practitioners was to interrupt transmission chains by quarantining patients.[7] The EVD response privileged the work of scientists often overlooking social and cultural factors. Medical intervention was highly individualistic and included enforced quarantines, movement prohibition, traveller test points, and mandated cremation. Unsurprisingly, the effectiveness of such measures increased the stigmatisation surrounding the disease.[8] Medical practitioners used IgM ELISA tests, RT-PCR tests, biopsy samples and viral cultures to diagnose patients and limit the spread of ebola.

While there were no approved treatments, supportive care like the one recommended by the CDC was applied to alleviate the patients' suffering. This included: oral rehydration therapy, intravenous fluids, oxygen therapy, treating other infections if they occurred, and disinfecting surfaces with (>70%) alcohol wipes. Conventional medicine was used to relieve the symptoms (high blood pressure, vomiting, fever and pain).[9][10] Medical workers used experimental treatments such as immune serums, antiviral drugs and possible blood transfusions to impede the disease from victimising others. To provide relief, the doctors deployed in the infected areas set up treatment and isolation centres rather than search for a cure. Containment was the main concern so medical action was largely unquestioned.[11]

Yet this approach was occasionally met with hostility for example when 8 health workers attempting to raise awareness about EVD in a village in Guinea were murdered.[12] While historically very effective at minimising physical suffering, the massacre of health workers made it painfully clear that this historical authority is not universal. Therefore, medics must turn to anthropologists to understand the important cultural dynamics present in diverse African societies.[13]

2. Anthropological Approach

[edit | edit source]Anthropological research illustrates how social and cultural factors contributed to the biological transmission of EVD during the 2013 West Africa outbreak and interfered with the corresponding medical response. Many of the affected countries suffer from poverty and the recent civil wars in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone left behind fragile health care systems and physician shortages regionally.[14] The consequent challenged quarantine, ineffective alerts and pleas for assistance facilitated further infection.[7]

Understanding cultural practices in infected regions is integral to tackling the EVD crisis effectively. Cultural differences between health practitioners and locals was problematic in dealing with the outbreak. The WHO’s retrospective analysis of the outbreak showed locals feared how much western treatment contradicted traditional practices regarding the dying or diseased.[14] Ancestral funeral rites such as sleeping next to an infectious corpse of the community and bathing in water used to rinse corpses were attributable to 80% of cases in Sierra Leone by WHO estimates. The stigma around these cultural practices drove families to hide symptomatic relatives, leading to infection of their households. Traditions of returning dying patients to their native village elevated the risk of transmission through cross-border movement.[7]

Fear of physicians was another barrier to its eradication. In Guinea, rumours of health workers disinfecting a market contaminating people led to riots. Proving that health care responses require communication between medical practitioners and community leaders.[15] A post-colonial reading of western aid sees imperialistic thinking that disregards customs. Doctors often see locals' apprehension of western medicine as backwards tradition and the work of well-respected African healers is disregarded. Biology failed to provide a complete explanation nor complete response to EVD epidemic. Anthropological research is needed to provide culturally-sensitive aid. Moreover, theology could further inform anthropology in local religious customs.

3. Theological Approach

[edit | edit source]Burials according to biomedicine and theology present contradictory practices. Biomedicine, a Western discipline, institutionalises quarantines in burials,[16] whereas West African religious preach religious inquires into pathology during burials.[17]

Burials are important in many West African religions, as the time for the deceased to enter the afterlife, join their ancestors, and overlook the living. Ill-performed rituals could trap the spirits in the living realm and taunt loved ones.[18] Bodies are cleansed and foetuses are removed from pregnant bodies to uphold natural cycles and ensure the wellbeing of both alive and dead.[19][20] Thus, religious procedures concerning remains are strictly adhered to. Disagreements over how burials should be performed have arisen during the outbreak because the meaning of burials diverges between biomedicine and West African theology. An example of this is, in Guinea, a burial was brought to standstill amidst disagreements between a Kissi family and the medical team on how to handle the remains. The body rotted as the dispute carries on, which risked further infections upon leakage.[17][21] Meanwhile, another team in Guinea substituted old repatriation rituals for the foetus’ removal, and successfully buried the pregnant body to everyone’s satisfaction.[19][21] This underpins the importance of theology in complementing biomedicine and anthropology to understand, manage, and quell epidemics like Ebola in West Africa.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]The 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic captured the world’s attention, and experts from a diverse range of disciplines sprang into West Africa’s aid; with medics handling the majority of ailments, while anthropologists liaised with communities, and religious leaders encouraging cooperation.

Unfortunately, due to the complex lexicon, disciplinary boundaries, and historical paradigms behind these disciplines; their ideas diverge on many seemingly intuitive concepts like burials, and could not communicate effectively. An interdisciplinary approach bridging knowledge between disciplines in their interpretation of treatment, healing, and well-being, could converge the efforts with synergetic effects.

Further disciplines may also be introduced, such as mathematical models of disease transmission, governance theories of public healthcare, and psychological perspectives on trauma. While each discipline has developed distinct metrics and criteria for what a good approach is, coherence could be achieved between these knowledge frameworks if differences are proactively reconciled.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. 2019. 2014-2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa. [cited 2019Dec5]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html

- ↑ Boseley S. Ebola crisis – the story in brief [Internet]. The Guardian. Guardian News and Media; 2015 [cited 2019Dec5]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/25/-sp-ebola-crisis-briefing

- ↑ Zawilińska B, Kosz-Vnenchak M. General introduction into the Ebola virus biology and disease [Internet]. Folia medica Cracoviensia. U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2014 [cited 2019Dec5]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25694096

- ↑ Servick K. Science. What does Ebola actually do? [Internet]. 13 August 2014. [Accessed 5 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2014/08/what-does-ebola-actually-do

- ↑ Wambani RJ, Ogola PE, Arika WM, Rachuonyo HO, Burugu MW. Ebola Virus Disease: A Biological and Epidemiological Perspective of a Virulent Virus. Journal of Infectious Diseases and Diagnosis [Internet]. 2015Jan26 [cited 2019Dec5];1(1):2–4. Available from: https://www.longdom.org/open-access/ebola-virus-disease-a-biological-and-epidemiological-perspective-of-avirulent-virus-jidd-1000103.pdf

- ↑ Henao-Restrepo AM, Camacho A, Longini IM, Watson CH, Edmunds WJ, Egger M. Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine in preventing Ebola virus disease: final results from the Guinea ring vaccination, open-label, cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet [Internet]. [cited 2019Dec8];389:505–18. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(16)32621-6/fulltext

- ↑ a b c Factors that contributed to undetected spread of the Ebola virus and impeded rapid containment [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2015 [cited 2019Dec6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/one-year-report/factors/en/

- ↑ Pellecchia U, Crestani R, Al-Kourdi Y, Drecoo T, Van den Bergh R. Social Consequences of Ebola Containment Measures in Liberia. National Centre for Biotechnology Information [Internet]. [cited 2019Dec8];10(12). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4674104/#__ffn_sectitle

- ↑ Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease) Treatment [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 [cited 2019Dec8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/treatment/index.html

- ↑ Oleribe OO. Ebola virus disease epidemic in West Africa: lessons learned and issues arising from West African countries. Royal College of Physicians [Internet]. 2015Feb [cited 2019Dec8];15(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4954525/#__ffn_sectitle

- ↑ Davis CP. Ebola Virus Vaccine, Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, Contagious [Internet]. MedicineNet. 2019 [cited 2019Dec8]. Available from: https://www.medicinenet.com/ebola_hemorrhagic_fever_ebola_hf/article.htm

- ↑ Phillip A. Eight dead in attack on Ebola team in Guinea. ‘Killed in cold blood.’ The Washington Post [Internet]. 2014Sep18 [cited 2019Dec8]; Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2014/09/18/missing-health-workers-in-guinea-were-educating-villagers-about-ebola-when-they-were-attacked/

- ↑ Obeng-Odoom FMB, Bockarie MMB. The Political Economy of the Ebola Virus Disease. Social Change [Internet]. [cited 2019Dec8];48(1):18–35. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0049085717743832

- ↑ a b Calnan M, Gadsby EW, Kondé MK, Diallo A, Rossman JS. The Response to and Impact of the Ebola Epidemic: Towards an Agenda for Interdisciplinary Research. National Centre for Biotechnology Information [Internet]. 2017Sep3 [cited 2019Dec7];7(5):402–11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5953523/

- ↑ Scott V, Crawford-Browne S, Sanders D. Critiquing the response to the Ebola epidemic through a Primary Health Care Approach. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2016May17 [cited 2019Dec6];16(1). Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-016-3071-4#ref-CR4

- ↑ Kinsman J, Angrén J, Elgh F, Furberg M, Mosquera AP, Otero-García L, et al. Preparedness and response against diseases with epidemic potential in the European Union: a qualitative case study of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and poliomyelitis in five member states. Bmc Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2018 Jul [cited 2019 Dec 2];18(528). Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-018-3326-0+doi:+10.1186/s12913-018-3326-0

- ↑ a b Fassassi A. How Anthropologists Help Medics Fight Ebola in Guinea [Internet]. SciDevNet [2014 Sep 24] [cited 2019 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.scidev.net//global/cooperation/feature/anthropologists-medics-ebola-guinea.html

- ↑ Anderson A. African Religions. In: Kastenbaum R, editors. Macmillan Encyclopedia of Death and Dying. 1st ed. New York: Macmillan Reference USA; 2003. p. 9-13

- ↑ a b Maxmen A, Muller P. An Epidemic Evolves - How the Fight Against Ebola Tested a Culture’s Traditions [Internet]. National Geographic [2015 Jan 30] [cited 2019 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2015/01/150130-ebola-virus-outbreak-epidemic-sierra-leone-funerals/

- ↑ Manguvo A, Mafuvadze B. The Impact of Traditional and Religious Practices on the Spread od Ebola in West Africa: Time for a Strategic Shift. Pan Afr Med J [internet]. 2015 Oct [cited 2019 Dec 2]; 22(Suppl 1):9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4709130/+doi:+10.11694/pamj.supp.2015.22.1.6190

- ↑ a b World Health Organization. What We Know About Transmission of the Ebola Virus Among Humans [Internet]. World Health Organization [2014 Oct 6] [cited 2019 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/ebola/06-october-2014/en/

The Issue of History in Wellbeing

Introduction

[edit | edit source]The term “well-being” was first utilised in 1561, denoting that a person or a community is healthy, happy, or prosperous; physical, psychological, or moral welfare.[1] It is commonly understood as the desirable state of life and, although the English term arose recently, well-being has always been pursued by mankind. It is therefore investigated in various disciplines, though each one has created its definition of it, prioritising certain aspects of well-being over others. In the following paragraphs, the current theories of “well-being” in various disciplines and historical root of disciplinary boundaries will be elucidated by presenting the possible formation of their paradigms.[2]

Wellbeing in Disciplines

[edit | edit source]Wellbeing within Economics

[edit | edit source]Economics is a discipline that is built fundamentally on the belief that humans have unlimited wants but limited resources[3]. Economists believe that efficiency and productivity are critical as this reduces scarcity, increasing the quality of life[4] Before, wellbeing was present indirectly through the concept of utility (defined as the total satisfaction received from consuming a good or service)[5]., which was integral to the discipline[6]. Early neoclassical economists believed that goods and services could be assigned numerical values where consumption estimated the consumer's happiness[7].Thus, they believed that the Gross Domestic Product was an appropriate indicator of well-being and that maximising economic growth was the key to improving it. However, this seemed to shift starting from the 1970s[8] due to Easterlin's research (1974) revealing that people in higher-income countries were not necessarily happier than those in lower-income ones[9]. Henceforth, economists became more aware of their overly-reductionistic view of well-being; besides material well-being, there was a need to recognise subjective and relational well-being [10]. This led to the rise of “happiness economics” (observing the effect of economic and social indicators on individual happiness) and quality of life indices, which saw a shift from a focus on GDP to economics becoming more people-centric[11].

Wellbeing within Philosophy

[edit | edit source]Philosophy (Greek ϕιλοσοϕία, love of knowledge)[12] is a discipline exploring problems with the nature of existence, knowledge, morality, reason and human purpose.[13] Due to the emergence of philosophical inquiry, when Thales questioned the beginning of things,[14] philosophers started to adore reasoning the hidden truth of existence rather than deriving theories through empirical research.[15][16] Wellbeing was widely discussed among historical moral philosophers. Common debates included how to ensure one’s life went well, how to live well and whether well-being was objective or subjective. The earliest theory, by Aristotle, claims that “eudaimonia” is the highest achievement of men, accomplished by pushing one’s life to its limits and thus attaining excellence (aretē).[17] Another important theory is Hedonism, ( hēdonē, pleasure in Greek), argues that wellbeing is the experience of more pleasure over pain.[18] Desire Fulfillment Theory emerged in the 19th century, partly due to the rise of welfare economics, holding the opinion that well-being lies in the fulfilment of one's desires.[19] Lastly, "Objective list theories" holds that well-being is the result of a number of objective conditions rather than the subjective experience of pleasure or the fulfilment of subjective desires.[20]

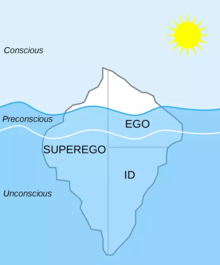

Wellbeing within Neuroscience (Psychology and Biology)

[edit | edit source]The key hypothesis of positive health is that well-being will be accompanied by the optimal functioning of multiple biological systems. This biopsychosocial interplay is proposed to comprise part of the mechanistic processes that help the individual maintain functional health, and thereby extended periods of quality living[21]. Researchers argue that biological factors such as the hormonal and neurochemical levels produced by one’s brain play a significant role in the wellbeing of an individual[22]. Neuroscience studies showed that parts of the brain and neurotransmitters play a role in controlling happiness, which contributes to one’s well-being. However, a study regarding antidepressants showed that though these medications immediately boost the concentration of chemical messengers in the brain (neurotransmitters) yet people typically don't begin to feel better for several weeks or longer[23]. Experts have long wondered why, if depression was primarily the result of poor well-being, people do not feel better as soon as levels of neurotransmitters increase. This led to the paradigm shift that although a substantial proportion of the variance in well-being can be attributed to heritable and biological factors such as health, environmental, psychological and economic factors play an equally important role[24].

Evaluation

[edit | edit source]As expounded above, despite several overlaps, the four different disciplines demonstrate diverging perspectives and approaches towards well-being. This shows how, when faced with a subject as abstract and undefined as well-being, the history of disciplines can become an obstacle to interdisciplinary research. Firstly, the fundamental beliefs and focus of the disciplines led them to define well-being inconsistently. The reduction of opportunity cost, decision-making and resources are critical building blocks in economic theory and thus, the narrowed economists' viewpoint of well-being being dependent on materialistic gains. Thus, even though subjective well-being data arose in the 1970s in Economics, there was still a general aversion and sceptical attitude towards it until the 1990s when happiness economics finally took off[25]. On the other hand, philosophy and psychology are more interested in the individual. This drives them to prioritise subjective well-being which is demonstrated by well-respected theories such as the Desire Fulfilment Theory. Unfortunately, this causes them to neglect the importance of material well-being. Secondly, methodology interferes with interdisciplinary collaboration. In philosophy, the theories about well-being were largely derived based on a process of intuition and logical reasoning. However, in medicine, such methods are not well-recognized as the discipline's approach is traditionally built on empirical science. Since many determinants of health can be measured which leads to the possibility of diagnosis and it is a struggle to quantify well-being, any other aspect of well-being beyond physical health is often difficult to incorporate within the discipline and its practices[26]. Lastly, terminology that seems natural in a certain discipline could lead to misunderstandings and complications during interdisciplinary collaboration. For example, the definition of "happiness" is slightly different in Economics and Psychology. While Economics strongly ties "happiness" with prosperity, Psychology recognises "happiness" in terms of the pleasure one experiences[27]. Thus, this leads to discordance when they attempt to collaborate on the topic of well-being.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]For interdisciplinary research, it is important to understand the history of different disciplines. By tracing well-being’s development within relative disciplines, the differences in theories, lexicons,methodologies, threshold concepts and paradigms are glaringly obvious and demonstrate the factors resulting in interdisciplinary boundaries. However, an understanding of each discipline’s history helps overcome interdisciplinary conflicts, fostering collaborations. For instance, the emergence of experimental philosophy and analytic philosophy, which promotes the combination of empirical research with the traditional philosophical research methodologies, bridged the gap between Biology and Philosophy. When disciplines moved past their historical boundaries, the complex and multi-faceted nature of wellbeing could then be fully appreciated. For example, Carol Ryff’s six-factor model remains one of psychology’s most predominantly accepted models that measures an individual’s wellbeing to date. Her model amalgamates theories from John Stuart Mill, Abraham Maslow, Carl Jung and Aristotle[28]. Comprising of six elements from different disciplines, her model insinuates that an individual’s psychological wellbeing is determined by his or her external environment and its various factors, which is the most balanced portrayal of well-being.

References

[edit | edit source]Truth in Lie Detection through Neurolaw

Neurolaw combines law andneuroscience and explores how neuroscientific findings are applied legally.[29] At the centre of neurolaw lies the human brain as a critical factor in legal decision making and policy. Thus, neurolaw uses neuroscientific data for a better understanding of human behaviour to achieve a more accurate legal system.[30][31][32] Within a law context neuroscience is applied in subfields such as health law, constitutional law, employment law, or criminal law. Issues addressed range from potential implications of cognitive impairment on sentencing tonootropics to questions regarding techniques employed to gather neuroscientific data.[30]

Introduction

[edit | edit source]Techniques in Neurolaw

[edit | edit source]Neurolaw predominantly relies on brain imaging methods such as PET and fMRI.[30][31][32] These techniques explore aspects of human cognition including intention, morality, and decision making.[33] PET and fMRI acquire data about brain activity during a specific perceptual or cognitive task. Both measure time-dependent changes in local blood flow to determine the most active brain areas.[34]

Lie Detection

[edit | edit source]

Since the legal system often relies on witness accounts, it is important that those accounts are credible. Thus, central to the field is differentiating truth from lies and finding appropriate methods to do so. Different technologies for lie detection such as polygraphs and more recently fMRI data have since been considered.[35] A polygraph is a device measuring autonomic body responses including heart rate, respiration, blood pressure and galvanic skin reactions in response to specific questions presented to a person.[36] fMRI lie detection rests on the assumption that cognitive processes, including deception, are reflected by brain physiology. Brain regions such as the IFG, IPL, MFG and SFG have been implicated in lying.[37]

However, the controversy about using neuroscientific lie detection technology is ongoing and it is likely that interdisciplinary epistemological differences concerning truth lie at the centre of the debate.

Truth in Neuroscience & Law

[edit | edit source]Truth in Neuroscience

[edit | edit source]Neuroscience uses positivism and interpretivism when approaching truth.

Positivism asserts that truth is exclusively verifiable through experimentation, observation and logic.[38] Neuroscientists conduct research through observing brain activity using MRI scans, computerised 3D models and experiments involving cells and tissues to develop new treatments.[39] As neuroscientists approach truth objectively by observing and experimenting, neuroscience is predominantly positivist.

Interpretivism emphasises qualitative analysis, employing various methodologies to reflect multiple aspects of an issue.[40] For example, as feelings reflect the ability to subjectively experience states of the nervous system, it is difficult to study them empirically as direct metrics cannot quantify changes unambiguously. Thus, indirect methods based on theoretical inferences are used.[41] The subjective nature of interpretivism facilitates the understanding of subjective phenomena.

Truth in Law

[edit | edit source]While law uses positivism, it also relies on social constructionism when approaching truth.

Positivism is used in judicial decision making. In a court of law, evidence is introduced to a judge or jury as proof; with admissible evidence being reliable documents, testimony and tangible evidence relevant to the case.[42] Empirical facts and logic are important legally, such as the proof of a defendant's guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

Social constructionism emphasises that "truth" is constructed by social practices, human interactions and language use.[43] In criminal law, the legality of behaviour lies in its social response rather than its content, with behaviours criminalised through social construction. The legality of behaviour can be changed by social movements; while criminality is perceived differently across cultures and time.[44] As crime is constructed socially, social constructionism is useful in understanding truth in law.

While neuroscience and law both use positivist views, the interpretivist aspects of neuroscience are distrusted in a legal context, resulting in debates such as the admission of fMRI lie detection evidence in court.

Conflicting Truth in Lie Detection

[edit | edit source]Case Study

[edit | edit source]

United States v. Semrau [45] illustrates the difference in interpreting truth between law's positivism and neuroscience's interpretivism. To convict the plaintiff of defrauding the healthcare benefit programme, it was necessary to prove that Semrau acted knowingly. Semrau’s appeal presented a fMRI lie detection test, testified by Dr. Steven J. Laken, CEO of Cephos Cooperation, a company that claims it uses “state-of-art-technology that is unbiased and scientifically validated” in its investigation services.[46]

Tension in Views of Truth

[edit | edit source]United States v. Semrau shows that using fMRI data as evidence to verify the credibility of people's accounts is controversial. In this case the plaintiff's fatigue affected his brain scans causing inconsistencies in results.[47] This reflects a more general issue of using fMRI data in a legal context. Research on lie detection and conclusions gathered from it are usually generated in a controlled experimental setting. However, the conditions under which people try to detect lies in court are very different from the conditions usually employed in scientific experiments. Therefore fMRI data may not have sufficient external validity in court.[48] For instance, there is no perfect correlation between deception and physiological response,[49] data gathered from arousal patterns can result in false positives[50] and, as it was the case in United States v. Semrau, a person's condition can affect the results. Thus, the possibility of falsifying true narratives through erroneously interpreting empirical data raises legal liability.

Consequently, how truth is presented and interpreted is limited by legal admissibility. The prevailing tension in whether legal or neuroscientific standards should be used to determine the admissibility of brain-based lie-detection in courtrooms stems from the extent to which brain scans can demonstrate that they indeed identify what they claim to be measuring. Brain images have no inherent significance without interpretation. However, when presented as evidence to the jury in the course of a trial, they raise questions regarding the concept of truth in the legal system.

The decision to use fMRI data to prove one's innocence depends on the extrapolation between laboratory results and real life lie detection. If the laboratory results match real life lie detection, the jury may place higher evidentiary value on that fMRI data. In United States v. Semrau, fMRI evidence was excluded due to inconsistencies in tests administered to the convicted and the lack of real world examination of fMRI technology[51]

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]United States v. Semrau illustrates the controversial views on truth from neuroscience and law: the courts deemed fMRI as lacking in reliability. In law, only evidence that is reliable and relevant is admissible. In neuroscience, interpretivism is necessary to relate the observed phenomenon to human subjective will. Lie detection evidence, which is partially based on interpretivist assumptions, is potentially inaccurate in analyzing people’s behaviors and thoughts, whereas courts require firm empirical evidence for the judicial process.

The interpretivist aspect of lie detection affects its judicial credibility. Thus, the distrust of interpretivist truths in law may be the main cause of the current dilemma: lie detection technology, as an upcoming product of neuroscientific development, is not yet an acceptable method to provide admissible evidence in the legal system.

Nevertheless, as techniques of gathering evidence improve, neuroscientific lie detection may reach a level of reliability that permits its use in judging criminal cases in the future.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Oed.com. (2019). Home : Oxford English Dictionary. [online] Available at: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/227050?redirectedFrom=well-being#eid [Accessed 25 Nov. 2019].

- ↑ Kvasz, L. (2014). Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions between sociology and epistemology. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, [online] (46), pp.78-84. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2014.02.006.

- ↑ 3. Chappelow J. Economics: Overview, Types and Economic Indicators [Internet]. Investopedia. 2019 [cited 6 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/economics.asp

- ↑ Chappelow J. Economics: Overview, Types and Economic Indicators [Internet]. Investopedia. 2019 [cited 6 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/economics.asp.

- ↑ 4. Chappelow J. Utility [Internet]. Investopedia. 2019 [cited 6 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/u/utility.asp

- ↑ Brey, P., Briggle, A. and Spence, E. (2012). The Good Life in a Technological Age. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis, p.23.

- ↑ Brey, P., Briggle, A. and Spence, E. (2012). The Good Life in a Technological Age. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis, p.23.

- ↑ Brey, P., Briggle, A. and Spence, E. (2012). The Good Life in a Technological Age. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis, p.23.

- ↑ 8. Brey P, Briggle A, Spence E. The Good Life in a Technological Age. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis; 2012.

- ↑ McGregor, J. and Pouw, N. (2017). Towards an economics of well-being. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 41(4), pp.1134-1135.

- ↑ Brey, P., Briggle, A. and Spence, E. (2012). The Good Life in a Technological Age. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis, p.23.

- ↑ Oed.com. (2019). Home : Oxford English Dictionary. [online] Available at: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/142505?rskey=uh0g5l&result=1#eid [Accessed 17 Nov. 2019]

- ↑ Jenny Teichmann and Katherine C. Evans, Philosophy: A Beginner's Guide (Blackwell Publishing, 1999), p. 1: "Philosophy is a study of problems which are ultimate, abstract and very general. These problems are concerned with the nature of existence, knowledge, morality, reason and human purpose."

- ↑ Sassi, M., & Asuni, M. (2018). The Beginnings of Philosophy in Greece. (pp1-31) PRINCETON; OXFORD: Princeton University Press. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1zk0msh

- ↑ Lewes. Library ed., much enlarged and thoroughly rev.(1871). The biographical history of philosophy: From its origin in Greece down to the present day. New York, NY, US: D Appleton & Company. p.3: “Hitherto men had contented themselves with accepting the world as they found it; with believing what they saw; and with adoring what they could not see.”

- ↑ ed Honderich, ed. (2005). "Conceptual analysis". Oxford Companion to Philosophy New Edition (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press USA. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7. "Insofar as conceptual analysis is the method of philosophy (as it was widely held to be for much of the twentieth century), philosophy is a second-order subject because it is about language not the world or what language is about.”

- ↑ Moran, J. (2018). ARISTOTLE ON EUDAIMONIA (‘HAPPINESS’). Think, 17(48), pp.91-99.

- ↑ Tännsjö, T. (1996). Classical hedonistic utilitarianism. Philosophical Studies, 81(1), pp.97-115.

- ↑ Chris Heathwood, Desire-Fulfillment Theory, draft of November 27, 2014

- ↑ Christopher M. Rice, Defending the Objective List Theory of Well‐Being, Ratio, Volume 26, Issue 2, P 196-211, June 2013

- ↑ Park, Nansook, et al. “Positive Psychology and Physical Health: Research and Applications.” American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, SAGE Publications, 26 Sept. 2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6124958/.

- ↑ Dfarhud, Dariush, et al. “Happiness & Health: The Biological Factors- Systematic Review Article.” Iranian Journal of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Nov. 2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4449495/.

- ↑ Harvard Health Publishing. “What Causes Depression?” Harvard Health, June 2009, https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression.

- ↑ Hernandez, Lyla M. “Genetics and Health.” Genes, Behavior, and the Social Environment: Moving Beyond the Nature/Nurture Debate., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 1970, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19932/.

- ↑ 5. Clark A. Four decades of the economics of happiness: Where next?. The review of income and wealth [Internet]. 2018 [cited 6 December 2019];64(2):245. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/roiw.12369

- ↑ 7. Martino L. Section 3: Concepts of health and wellbeing [Internet]. Health Knowledge. 2019 [cited 8 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.healthknowledge.org.uk/public-health-textbook/medical-sociology-policy-economics/4a-concepts-health-illness/section2/activity3

- ↑ 6. Kimball M, Willis R. Utility and Happiness. 2005.

- ↑ “Carol Ryff's Model of Psychological Well-Being.” Living Meanings, 2 Aug. 2016, http://livingmeanings.com/six-criteria-well-ryffs-multidimensional-model/.

- ↑ Wolf SM. Neurolaw: the big question. AJOB [Internet]. 2008 Jan; 8(1):21-22. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15265160701828485 DOI: 10.1080/15265160701828485

- ↑ a b c Petoft A. Neurolaw: a brief introduction. Iran J Neurol [Internet]. 2015 Jan; 14(1): 53-58. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4395810/

- ↑ a b Petoft A, Abbasi, M. A historical overview of law and neuroscience: from the emergence of medico-legal discourses to developed neurolaw. Archivio Penale [Internet]. 2019 1(3): 1-42. Available from www.archiviopenale.it/File/Download?codice=830489da-90d0-4f0d-9f9f-79780b98a155

- ↑ a b Tigano V, Cascini GL, Sanchez-Castañeda C, Péran P, Sabatini U. Neuroimaging and neurolaw: crawing the future of aging. Front Endocrinol [Internet]. 2019 Apr; 10:1-15. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6463811/ DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00217

- ↑ Gazzaniga MS. The law and neuroscience. Neuron [Internet]. 2008 Nov; 60(3): 412-5. Available from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0896627308008957 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.022

- ↑ Rajapakse JC, Cichocki, A, Sanchez, VD. Independent component analysis and beyond in brain imaging: EEG, MEG, fMRI, and PET. In: Wang L, Rajapakse JC, Fukushima K, Lee S, Yao X editors. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Neural Information Processing (ICONIP '02). IEEE; 2002. 2002 Nov 18-22; p. 404-12. Available from https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/1202202/citations#citations

- ↑ Schauer F. Neuroscience, lie-detection, and the law: contrary to the prevailing view, the suitability of brain-based lie-detection for courtroom or forensic use should be determined according to legal and not scientific standards. Trends Cogn Sci [Internet]. 2010 Mar; 14(3): 101-3. Available from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364661309002848 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.004

- ↑ Fiedler K, Schmid J, Stahl T. What is the current truth about polygraph lie detection?. Basic Appl Soc Psych [Internet]. 2010 Jun; 24(4): 313-24. Available from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15324834BASP2404_6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2404_6

- ↑ Farah MJ, Hutchinson, JB, Phelps EA, Wagner, AD. Functional MRI-based lie detection: scientific and societal challenges. Nat Rev Neurosci [Internet]. 2014 Jan; 15:123-31. Available from https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn3665

- ↑ Positivism [Internet]. Philosophy Terms. 2019 [cited 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://philosophyterms.com/positivism/

- ↑ What is Neuroscience? [Internet]. Medical News Today. 2019 [cited 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/248680.php#why-is-neuroscience-important

- ↑ Interpretivism (interpretivist) Research Philosophy [Internet]. Research Methodology. 2019 [cited 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://research-methodology.net/research-philosophy/interpretivism/

- ↑ Panksepp J. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- ↑ Tran J. What Is Admissible Evidence? [Internet]. LegalMatch. 2018 [cited 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.legalmatch.com/law-library/article/what-is-admissible-evidence.html

- ↑ Andrews T. What is Social Constructionism? | Grounded Theory Review [Internet]. Grounded Theory Review. 2019 [cited 27 November 2019]. Available from: http://groundedtheoryreview.com/2012/06/01/what-is-social-constructionism/

- ↑ Rosenfeld R. The Social Construction of Crime [Internet]. Oxford Bibliographies. 2019 [cited 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195396607/obo-9780195396607-0050.xml

- ↑ United states vs Semrau (U.S Dist. Ct. W. Dist. Of TN 2010) No. 07-10074. [Internet]. Opn.ca6.uscourts.gov. 2012 [cited 5 December 2019]. Available from: http://www.opn.ca6.uscourts.gov/opinions.pdf/12a0312p-06.pdf

- ↑ Bioethics and the law. Scitech Book News 2005 12;29(4). [cited 5 December 2019]. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/200233732

- ↑ United states vs Semrau (U.S Dist. Ct. W. Dist. Of TN 2010) No. 07-10074. (p.9) [Internet]. Opn.ca6.uscourts.gov. 2012 [cited 5 December 2019]. Available from: http://www.opn.ca6.uscourts.gov/opinions.pdf/12a0312p-06.pdf

- ↑ Schauer F. Neuroscience, lie-detection, and the law. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2010;14(3):101-103. [cited 5 December 2019]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.004

- ↑ Moore M. The Polygraph and Lie Detection. DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. Chapter 5, p.67. [cited 5 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/read/10420/chapter/5#67

- ↑ Moore M. The Polygraph and Lie Detection. DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. Chapter 4, p.31. [cited 5 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/read/10420/chapter/4#31

- ↑ United states vs Semrau (U.S Dist. Ct. W. Dist. Of TN 2010) No. 07-10074. (p.6) [Internet]. Opn.ca6.uscourts.gov. 2012 [cited 5 December 2019]. Available from: http://www.opn.ca6.uscourts.gov/opinions.pdf/12a0312p-06.pdf

Truth in the Ted Bundy Case

Truth in the Ted Bundy Case

[edit | edit source]Introduction

[edit | edit source]The Ted Bundy trial is one of the most notable criminal cases in US history as there was a huge disconnect between the public's perception and his crimes. The stark dichotomy between his self-presentation as the all-American boy and his heinous crimes was key to disorienting the public’s perception.[1] Since then, Ted Bundy has been of great interest in a variety of disciplines, including law, psycholinguistics, and journalism, all attempting to uncover the truth of his character and his crimes.

Bundy's Manipulation of the Truth

[edit | edit source]Psycholinguistics and Truth

Ted Bundy was known for his chameleonic personality. He was able to change his persona and behaviour to look different to different people. Some colleagues look back on him as a “compassionate counselor”, whilst others described him as “cold” and “lacking compassion”.[3] The combination of his intelligence, arrogance and charm made him both a compelling and repelling figure. Reporter Barbara Grossman aptly summarised the ‘Ted Bundy’ effect: "Sometimes I come away from an interview with Ted thinking I've got great stuff. But then the more you listen to what he says, the more you wonder what he's saying."[3]

Establishing truth in forensic contexts is a legal necessity, but becomes problematic when decisions of guilt and innocence become dependent on dialogue-based evidence. This is what happened in the Bundy case. In his final interviews, Bundy utilised the semantic field of innocence and vulnerability when describing his pornography addiction, as if he were not strong enough to withstand its allure. When speaking to the interviewer, he played to the 'all-American' archetype he knew he had been ascribed (“we are your sons”),[4] forging a deep connection with the public while drawing their attention away from his guilt.[5]

His assertions regarding pornography almost caused more controversy than his crimes, switching tactics as he began to blame society in the eleventh hour.[1] His psychopathic traits could be seen when Bundy manipulated his self-presentation (through his linguistic choices) to encourage the judge and public to create a sympathetic relationship towards him, a fallible man. Bundy created a constructivist version of his self-presentation, which did not match with reality. The subjective nature of truth is highlighted here as language can be interpreted differently. This means that everyone acquired a different perception of the reality, which was further emphasized by how the media approached his case.

Bundy in the Press

[edit | edit source]Journalism and Truth

Bundy’s trial was the first nationally televised trial in the United States. Reporters flocked to his 1979 trial, marking the beginning of a genre of proto-reality television shows: murder trials.[7]

Although journalists seek to provide a fair account of facts and verified data that correspond with reality, the often subjective tools employed may distort the truth. It is at their discretion to decide who and what to focus on.[8] Recorded clippings of his trial focused on the public persona Bundy constructed through psycholinguistics, meaning the audience failed to take into account the gruesome details of his crimes.

The introduction of this technological advancement in journalism influenced the public’s perception of his character: public defenders claimed he “was very conscious of the camera”, presenting himself as a charming young man. His grandiose stage presence, screaming and impulsively marrying a woman on the witness stand, was designed to stir up controversy, simultaneously shocking and delighting the audience. His persona was so convincing that some believed that he was framed and was actually innocent.[9]

Furthermore, he was careless when he wanted to be. His acknowledgement of this added to his paradoxical ‘devilish yet charming’ reputation (“I’m the most cold-blooded son of a bitch you’ll ever meet”).[10] This stage persona that he constructed skewed perceptions as the media broadcast this as the correspondent truth.[11]

As he was able to manipulate the camera, Bundy again created a constructivist version of his true character, then broadcast by the media as the correspondent truth. This exemplifies how journalism romanticised Bundy, creating a new contested version of the truth. The objective facts of him being a convicted murderer and rapist were overshadowed by his greater-than-nature persona. These perceptions then bled into the law, as one of the judges commented “I might say you look nice today, Mr. Bundy. I’m glad to see you in proper uniform”. His charisma was highlighted by the media and therefore, hindered the judge’s ability to rule out his case with absolute objective truth.[7]

Bundy Under the Law

[edit | edit source]

Law and Truth

The legal proceeding in an American court for criminals is that the accused person (i.e. Ted Bundy) is presumed innocent until there is enough proof to say otherwise (presumption of innocence).[13] After each side has made their case during a trial, the jury decides the sentence of the accused, reaching a decision in the most fair and informed way possible.[14] Therefore, the legal truth is based on what the attorney on each side can convince the jury of. If there is enough evidence to prove that the convicted is in fact guilty, a sentence will be decided. However, if the jury feels as if it does not have enough evidence to prove the convicted as being guilty, they will be released.

This positivist approach to the truth is very different to that in other disciplines as it states that the the accused is innocent until they are proven guilty. According to the empirical “legal truth”, Bundy was innocent at the beginning of his trials. This presumption of innocence led to his release when he was first arrested in August 16, 1975 by the Utah Highway patrol for suspicious equipment found in the back of his Volkswagen.[15]

When he was caught, the detectives did not have enough evidence to prove his involvement in the disappearance of five young women. Due to the structure of the American legal system, he was declared innocent and released from any further persecution. Had there been enough evidence to prove that he was guilty and had the legal truth reflected the absolute truth, many girls "would still be alive'', recalls Bob Hayward, the highway patrol sergeant who arrested Bundy. This reveals certain shortcomings in the legal approach to truth, which one might consider hindered by its positivist approach.[16]

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Reality can be seen through various perspectives. Journalism aims for correspondent truth, but this was skewed as who and what the media focused on, coupled with his linguistic manipulation, enabled him to construct an alternate self-presentation. This constructed truth presented by journalists subconsciously influenced the jury in Bundy’s favour. His manipulation through language bolstered this particular reality, further deepening the divide between the legal evidence against him and his outward persona.

Moreover, Ted Bundy made no attempts to appear innocent on camera, yet the legal system put forward an empirical stance due to the “presumption of innocence” principle. Consequently, the complexity of his case urges us to consider a pluralistic view of the truth: perhaps all these different iterations are facets of the same truth, thus an example of interdisciplinarity at work.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b Caputi J. The Sexual Politics of Murder. Gender & Society [Internet]. 1989;3(4):437-456. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/089124389003004003

- ↑ State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, Public Domain. Ted Bundy in court [Internet]. [cited 1 December 2019]. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14196442

- ↑ a b Ramsland K. The Bundy Effect [Internet]. Psychology Today. 2015. Available from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/shadow-boxing/201508/the-bundy-effect

- ↑ Dorman, C. (2018). Confession of Ted Bundy (open captions). [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7dyPvJxqzJg.

- ↑ Smithson R. Rhetoric and Psychopathy: Linguistic Manipulation and Deceit in the Final Interview of Ted Bundy. Diffusion: The UCLan Journal of Undergraduate Research. 2013;6(2).

- ↑ State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, Public Domain. Ted Bundy in court [Internet]. [cited 1 December 2019]. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14196442

- ↑ a b Lauredo M. Serial Killer Ted Bundy Found the Spotlight During His Miami Trial [Internet]. Miami New Times. 2019 [cited 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.miaminewtimes.com/arts/ted-bundy-murder-trial-in-miami-foreshadowed-true-crime-fandom-11070191

- ↑ The elements of journalism – American Press Institute [Internet]. American Press Institute. 2019 [cited 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/journalism-essentials/what-is-journalism/elements-journalism/

- ↑ Nordheimer J. All-American boy on Trial. The New York Times [Internet]. 1978 [cited 27 November 2019];. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/1978/12/10/archives/allamerican-boy-on-trial-ted-bundy.html

- ↑ Michaud S, Aynesworth H. Ted Bundy: Conversations With a Killer: The Death Row Interviews. Authorlink; 2000.

- ↑ Shelton J. How The Televised Trial Of Ted Bundy Created Reality TV [Internet]. Groovy History. 2019 [cited 27 November 2019]. Available from: https://groovyhistory.com/televised-trial-serial-killer-ted-bundy

- ↑ Ted Bundy's Volkswagen [Internet]. [cited 1 December 2019]. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11729891

- ↑ The American System of Criminal Justice | Stimmel Law [Internet]. Stimmel-law.com. 2019 [cited 15 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.stimmel-law.com/en/articles/american-system-criminal-justice

- ↑ Criminal [Internet]. Judiciary.uk. 2006 [cited 20 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/about-the-judiciary/the-justice-system/jurisdictions/criminal-jurisdiction/

- ↑ FRANCIS S. Trooper who arrested Ted Bundy dies at 90 [Internet]. GOOD4UTAH. 2017 [cited 19 November 2019]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20190126164504/https://www.abc4.com/news/local-news/trooper-who-arrested-ted-bundy-dies-at-90/785699510

- ↑ Ortiz M. Utah law enforcement helped bring Ted Bundy down [Internet]. abc4 news. 2015 [cited 22 November 2019]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20181125143628/https://www.abc4.com/good4utah/utah-law-enforcement-helped-bring-ted-bundy-down/206338966

Truth in Free Will

Introduction

[edit | edit source]Free will and the discussion surrounding its existence are pivotal to determining whether people can be held responsible for their actions.[1] In 2015, "Scientific American" found that 60% of its readers believed in free will, despite disciplines such as neuroscience providing new evidence to suggest that free will is an illusion, with neuroscientists proposing the alternative standpoint of determinism.[2]

One particularly unusual case demonstrates how the debate over the existence of free will is relevant to modern society.

Legal Case Study

[edit | edit source]This case saw a man take a sudden, previously non-existent interest in child pornography, making sexual advances towards his step-daughter and staff at a sexual rehabilitation centre despite a strong contradiction to his own moral compass. He was subsequently sentenced to prison for child molestation. After experiencing strong headaches and an uneven gait, he underwent a neurological exam, revealing a tumour that had displaced his right orbitofrontal lobe.[3] The tumour was removed and mere hours later his behaviour and gait had returned to normal. Later, his sexual deviancy recommenced and he began to experience more headaches, with brain scans indicating the tumour had returned. After having it removed, he appeared to have been cured again.

This begs the questions: to what extent is the man truly culpable for his sexual deviance? Were his actions caused by medical factors beyond his control? If so, do we need to rethink our laws to incorporate loss of free will?

Truth in Free Will

[edit | edit source]Free Will in Christianity

[edit | edit source]Christianity is characterized by its view that humans not only consist of a material body, but also a distinct non-material soul that connects them with God, who is entirely non-material. This substance dualism is opposed to the idea of materialism or monism, which claim that humans, like everything in the world, are governed solely by physical laws. Dualism allows for the existence of free will and the freedom to make alternative choices in life because the interactionalist mind or soul can act upon the physical brain.[4] Current theologians like Barth and Cobb also argue that human actions and intentions are not purely physically determined, but subject to self-determination, asserting the existence of agent-based free will within the discipline.

Christianity holds two truths closely; the parameters of good and bad deeds and the existence of free will. Moral freedom is therefore strongly linked to a specific moral code, to give up selfish desires and transcend to selflessly sacrificing oneself for one's neighbours. Every human is encouraged to follow that 'law' of model behaviour for their souls to rest in heaven. This law therefore regulates the decisions agents make with free will. Luther formulates this paradox as the Christian individual being "free lord of all; subject to none" whilst being a "dutiful servant of all, subject to all in love."[5]

Free Will and Christianity in US Law

[edit | edit source]Despite the fact that the US has secularism explicitly enshrined in their original constitution as well as the Bill of Rights, there are plentiful arguments proving that religion, particularly Christianity, still plays a significant role in US law. 125 religious lobbies like the Christian Coalition currently work at shaping legal processes and policies in favor of their ideologies.[6]

The strong connection between Christianity and US law could explain its implications regarding free will. Indeed, a comprehensive analysis of US law has found significant remnants of substance dualism within it.[7] This is evident with the standard of taking into consideration the intentions of an individual when attributing accountability for a criminal action, reinforcing ‘our identity as moral agents capable of making free choices' and making the assumption that we have conscious control over our physical brain, including our desires.[7] This is something modern neuroscience is finding to be an unsustainable view, prompting the need for reconsideration of these basal truths which have shaped the legal system.

Truth in Determinism

[edit | edit source]Determinism Demonstrated

[edit | edit source]Libet laid the foundations for determinism in modern neuroscience in an experiment where he found that the start-time of the neural activity to cause motor action preceded the time of conscious intention to act by at least several hundred milliseconds, suggesting conscious will has no role to play in causing the action.[8]

A stream of studies since have corroborated and extended Libet's findings.[9][10][11] Subsequently, leading neuroscientists such as Harris accept that unconscious activity begins before conscious conception of an action and therefore argue free will "cannot be mapped on to any conceivable reality".[12]

Neuroscientists attribute the unconscious activity to the biochemical function of the brain.[12] This makes it highly rational to dismiss free will after assessing these studies from a neuroscientific perspective. Yet, the fact that this particular conclusion has been drawn is based on the ideas of truth within the discipline with regards to theory of mind.

Physicalism in Neuroscience

[edit | edit source]Sperry's study of 'split brain' patients in 1968 demonstrates neuroscience's position on theory of mind. By performing experiments with patients who had previously had their corpus callosum severed, Sperry was able to show that both hemispheres of the brain could work independently of one another, with different functions.[13][14]

Remarkably, each hemisphere of the brain produced a distinct conscious personality, which occurred due to the alteration of brain structure.[15] This propelled the idea that all mental phenomena such as consciousness and the illusion of free will are determined by biological structure and function, resulting in the discipline strengthening its relation to physicalism.[16]

Positivism and physicalism in this way determine the ideas formed about free will within neuroscience.[17] It follows that an interactionalist mind is not considered a reason to explain where and how unconscious activity begins from a neuroscientific perspective, leading prominent figures in the discipline to discard free will and make determinism a truth itself.

Conflicts about Truth

[edit | edit source]An interdisciplinary approach to free will, applying neuroscience to law and philosophy in the emerging discipline of neurolaw, presents the opportunity to update our moral assumptions, and hence our social frameworks, relative to modern scientific consensus.[18]

Application to Case Study

[edit | edit source]To consider the neurological aspect of the aforementioned case study, we consider clinical psychologist Cantor's assessment of the culprit. He proposed that the tumour merely impeded the man’s decision making process, interfering with his ability to regulate his behaviour which had previously suppressed his internal paedophilic desires. Thus, with regards to free will and culpability, whether or not the man truly wanted to act on these sexual desires was irrelevant; he had no liberty to make a different choice given the composition of his brain, and therefore no had no free will.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]A complete overhaul of the foundational principles of law in respect to free will in attempt to reconcile these differences in truth may not necessarily lead to a more functional society. Psychological studies have shown people with a deterministic world view have a reduced sense of retribution and are more likely to cheat when the opportunity is provided.[19][20]

This demonstrates that the application of determinism to law may create focus on a system of rehabilitating and reintegrating offenders and construct a more reformative justice system. However, for a functional society the illusion of free will may need to be sustained. Further interdisciplinary cooperation may allow a practical resolution to be reached.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Fischer JM. The Oxford Handbook of Ethical Theory. Oxford University Press; 2004. Free will and moral responsibility; p.321.

- ↑ Scientific American. Site Survey Shows 60 Percent Think Free Will Exists [Internet]. 2015 Jan 15 [cited 2019 Dec 8]. Available from: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/talking-back/site-survey-shows-60-percent-think-free-will-exists-read-why/

- ↑ Burns JM, Swerdlow RH. Right Orbitofrontal Tumor With Pedophilia Symptom and Constructional Apraxia Sign. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(3):437-40.

- ↑ Calef S. Dualism and Mind. IEP. 2005. Available from: https://www.iep.utm.edu/dualism/#H5.

- ↑ Peters T. Free Will in Science, Philosophy, and Theology. Theol Sci. 2019;17(2):149-53.

- ↑ Davis DH. Law, the U.S. Supreme Court, and Religion. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. 2016 Aug 31. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.449

- ↑ a b Pardo MS, Patterson D. Philosophical foundations of law and neuroscience. U Ill L Rev. 2010.

- ↑ Libet B, Gleason CA, Wright EW, Pearl DK. Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). Neurophysiology of Consciousness. 1993:249-268.

- ↑ Fried I, Mukamel R, Kreiman G. Internally generated preactivation of single neurons in human medial frontal cortex predicts volition. Neuron. 2011 Feb 10;69(3):548-62.

- ↑ Bode S, He AH, Soon CS, Trampel R, Turner R, Haynes JD. Tracking the unconscious generation of free decisions using uitra-high field fMRI. PloS one. 2011 Jun 27;6(6):e21612.

- ↑ Soon CS, Brass M, Heinze HJ, Haynes JD. Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature neuroscience. 2008 May;11(5):543.

- ↑ a b Harris S. Free will. Simon and Schuster; 2012 Mar 6.

- ↑ Lienhard DA. Embryo Project Encyclopedia [Internet]. Arizona: ASU; 2017. Roger Sperry’s Split Brain Experiments (1959–1968); [cited 2019 Dec 5]. Available from: http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/13035.

- ↑ Sperry RW. Hemisphere Deconnection and Unity in Conscious Awareness. Am Psychol. 1968;28:723–33.

- ↑ Niebauer C. No Self, No Problem. Hierophant Publishing; 2019.

- ↑ Gligorov N. Determinism and Advances in Neuroscience. AMA J Ethics. 2012;14(6);489-493.

- ↑ Mastin L. The Basics of Philosophy. Physicalism [Internet]. 2019 [cited 5 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.philosophybasics.com/branch_physicalism.html

- ↑ Burns K, Bechara A. Decision Making and Free Will: A Neuroscience Perspective. Behav Sci Law 25. 2007:263-280

- ↑ Shariff AF, Greene JD, Karremans JC, Luguri JB, Clark CJ, Schooler JW, Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Free will and punishment: A mechanistic view of human nature reduces retribution. Psychological science. 2014 Aug;25(8):1563-70.

- ↑ Vohs KD, Schooler JW. The value of believing in free will: Encouraging a belief in determinism increases cheating. Psychological science. 2008 Jan;19(1):49-54.

Truth in The Nanjing Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre

[edit | edit source]

The Nanjing Massacre was an incident which occurred during World War II, where Japanese soldiers allegedly looted, raped and murdered their way through Nanjing.[2] However, there are few facts about the Nanjing Massacre that are universally accepted as truth.[3] The time frames claimed for the massacre ranges from three weeks, starting December 13,[3] to three months between December 1937 and February 1938,[2] and neither the geographical extent of the conflict, nor the number of victims have been agreed upon.[4] The number of victims claimed ranges from 100[2] to 300 000.[1]

Perspectives

[edit | edit source]History

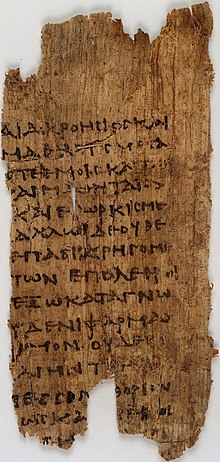

[edit | edit source]The purpose of history as a discipline is generally seen as finding the truth about the past.[5] However, it's debatable whether it's actually possible to find an objective, historical truth, or if such a truth exists. The Nanjing Massacre is an example that presents a challenge to "positivist empiricism"[4] in history. Different sources claim different facts about the event and due to both Chinese and Japanese suppression of the event at the time, there's a lack of primary sources.[2] This is problematic, since primary sources are key in historical research and constructing a historical narrative.[6] An additional aspect to the problem is that large amounts of propaganda was produced at the time, particularly in the form of photographs, which means the sources that do exist need to be critically examined and evaluated, with the possibility remaining that they might be false.[7]

Historian Daqing Yang argues that the closest one can get to a historical truth is through convergence in the arguments made by historians. He identifies four points on which there's convergence about the Nanjing Massacre:

- The Japanese army committed large-scale atrocities.

- The soldiers were acting under orders, not performing random acts of violence.

- Poor military tactics and confusion among the Chinese army contributed to the high number of losses.

- The Western International Safety Zone helped save many Chinese lives.[4]