History of Florida/Printable version

| This is the print version of History of Florida You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/History_of_Florida

Introduction

Overview of Florida

[edit | edit source]

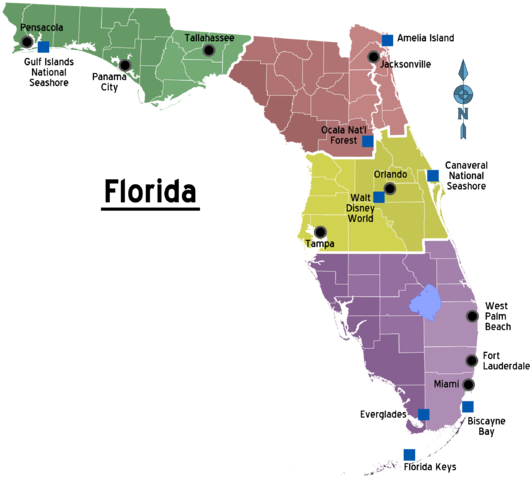

The State of Florida is often associated with palm trees, sun, beaches, and tourist attractions as it is commonly known as the “Sunshine State”. Including well-known cities like Miami, Orlando, Tampa and its capital city Tallahassee, all these locations have something in common: history, sunshine, and tourist appeal. Florida is the southern most U.S state with much Latin influence from it's Spanish decent. Over 18 million people reside in Florida. Nearly 25 percent of Florida’s population is Hispanic, which is reflected in the culture of many areas of the state. The second spoken language in Florida is Spanish, and it is especially prevalent in Miami. There is a large population of immigrants in modern day Florida. Florida is in close proximity to Central and South America so the majority of immigrants come from Cuba, Haiti, and Colombia.

Since warm weather is typically constant, Florida has also become famous worldwide for their exports of grapefruits, sugar and oranges. The citrus industry in Florida's popular culture brings state-wide pride. In 1967 for example, a Legislature was passed that stated that orange juice is "the official beverage of the State of Florida". Florida is also well known for its native animals like the American alligator. Although they were once hunted to near extinction, these alligators now thrive in the state and are mentioned throughout Florida’s popular culture. This ranges from tourist attractions to postcards and team mascots. Florida has a lot of biodiversity in general, and is also known for a large variety of species of birds (including the very popular flamingo), insects, turtles, snakes, lizards, among others.

Florida has also been prominently involved in America’s Space Age. Space has become an integral part of Florida’s economy and culture, offering thousands of jobs, as well as motels and restaurants adopting space themes to attract visitors and residents. Apollo 7, the first manned mission in the United States Apollo space program, was launched from Cape Kennedy Air Force Station in Florida on October 11th in 1967. Every U.S. astronaut that has gone into space has been launched from the station. Kennedy Space Center is a field center for NASA the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Built beginning in 1962, it has played a significant role in U.S. History as it is the location from which the first journey to the moon from the U.S.A. was launched. The creation of the Kennedy Space Center changed many things for the surrounding areas, such as shifting the main economic activity from agriculture to space. It is still in operation today and is a very popular tourist attraction as well.

Florida also has a rich sporting tradition encompassing a wide range. In baseball, it has 2 major league franchises, and hosts 17 spring training sites – the most of any state – a tradition that began in 1888. These 17 training camps make up what is known as the Grapefruit League. Golf has been a major game since its introduction in the late 1800s due to the flat land and climate of Florida. Football is also very popular, especially the University of Florida team, who attract, on average, over 85,000 fans every home game at the Ben Hill Griffin Stadium in Gainseville. Florida also has a rich tradition and history in the movie industry. The state was once referred to as “Hollywood East”, with many films being produced there from the early 20th century to the modern era. Florida is ranked 3rd in the nation for producing films.

Historical Overview

[edit | edit source]Early Beginnings

[edit | edit source]Before the Florida that the world knows today came to be, it used to be a land of dense woods, swamps, sand and coast upon which the waves beat restlessly. Beginning with Spanish conquests for gold, massive amounts of wealth was gained from traveling to the New World and soon enough passage was discovered by their explorer Ponce de Leon through a Florida channel. In 1513, Ponce de Leon lead the first European expedition to the unexplored territory of what would be Florida. The Spanish soon had royal orders from the homeland to protect their Florida territory by fortifying the coast in order to expel other nations and to avoid the robberies of their fleets. Ponce de Leon named the State in tribute to Spain’s Easter celebration, which is known as “Pascua Florida” or “Feast of Flowers”.

Later in 1565, another Spanish explorer, Pedro Menedez de Aviles, established the first permanent European settlement in St. Augustine. America’s first Christian church, first hospital, and first school were all established in St. Augustine. During the time of the American Revolution, the possession of Florida was still unresolved and the Spanish, French and English were battling the aboriginals for the territorial rights of the land. While not completely ideal with its swampy areas, parts of Florida was quite sufficient for plantation agriculture but also its navigable rivers made trade very attractive. The attention given to Florida by the Spanish made it appealing for others interested in expanding. Florida bounced between Spanish and British rule for the majority of the 16th and 17th centuries before it gained statehood after the Louisiana Purchase and the revolutions of East and West Florida. Prior to being sold to the United States, Florida was both a state within Spain and Britain at two separate times.

Overview of Historical Injustice in Florida

[edit | edit source]The history of Florida demonstrates a large amount of liberty and the struggle to define the state, achieve power and recognition. The portrayal of Florida as a land of equal opportunity and remaining the diverse territory it was, makes the struggle for equality a crucial and interesting part of the state's history. Over the course of Florida’s development toward becoming the world recognized state it is today, it was marked by both success and failure, dealing with racism and white supremacy. The state remarkably handled both integration and segregation seamlessly to construct the illusion of acceptance while being pro equality and inequality. Florida was perceived by Northern migrants as progressive, granted the sizable black population residing in the state alongside an influx of new coloured immigrants from places throughout the Bahamas and Caribbean. Prior to becoming president, General Andrew Jackson led an invasion of Seminole Indians in Spanish-controlled Florida in 1817. The underlying reality after going under American control depicted Florida as far from progressivism as the State actually decreed many laws that would belittle and even dismiss the rights the black community had received under Reconstruction.

Florida had a massive plantation culture during the antebellum period, with cotton being produced at a very high rate. Just before the Civil War in 1860, slaves made up for more than half of Middle Florida’s population. Florida was one of the more unique Confederate states in the Civil War, mainly contributing goods than manpower to the war effort. This was due to their geographical location and proximity to the sea. Only 15,000 soldiers were supplied by the state. Florida became the 27th State to join the Union on March 3rd, 1845.

The state also went through internal wars with different Native American tribes which underwent severe racial segregation. When white settlers began to increase in Florida, this put pressure on the U.S. government to remove the Indians from the state. The war between the Seminole Indians and the United states lasted for many decades and was not only a land dispute but as well a struggle for freedom and struggle for power played out over a wild landscape that shaped the future for both sides and possession of the state. In 1832, the U.S. government signed the Treaty of Payne’s, which was imposed in order to eliminate Seminole Indians from Florida, but most refused to leave. The government had to resort to force in order to get them out of Florida and this lead to the second Seminole War.

Even throughout the 1950's and 1960's Florida continued to enforce segregation, installing a “whites only” and “blacks only” bifurcated society. Lynching became a common phenomenon. In the first half of the century, Florida led the nation with the highest number of lynchings per capita. Along with “black” and “white” street signs, other forms of blatant racial intolerance included Florida’s rejection of segregated school systems, decreasing black voters, harassment and persecution, termed “red-baiting”, and rejecting all legal attempts of integration and giving aid to the black community within the State of Florida. These acts are quite surprising in comparison to the image the State liked to uphold for the tourists, however misleading it may have been. The racist undertones of Florida are almost understandable when thinking of the State’s neighbors, Georgia and Alabama, who were rabidly segregationists. Florida was a divided State, where the “New South” pushed for integration and equal opportunity while covering up the “Old South” who firmly held onto their past of racial prejudices and white supremacy. Many African-Americans from Florida played a pivotal role against this in the wider Civil Rights Movement, with a couple of examples being the Tallahassee Bus Boycott which lasted for 7 months in 1956 and the first sit-in in at Tallahassee on February 13, 1960.

Early Economic Growth

[edit | edit source]The State of Florida was not as affected by the United States economic expansion during the nineteenth century like other settlements around the newly formed nation. While Florida possessed ample land and an inviting climate, this was not enough to encourage settlers and travelers to ignore the aboriginal warfare that occurred up to 1850 and the tropical diseases like malaria that was known to wipe out entire communities. By 1880 however, travel to Florida began to grow and expand during its first industrial and agricultural boom. From this point and for the rest of the century, the capitalistic "Gilded Age" had began that resulted in a great contrast in wealth and huge corporations now dominated the consumer market. The wealthy upper class now looked to spend their great amounts of disposable income on sources of entertainment and often turned towards Florida for their beaches and warm weather.

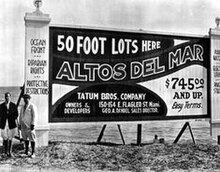

Florida, during this era also become attractive to new settlers as, in order to lure tourists to their own resorts in 1880, Henry Flagler and H.B. Plant began their development of new rail networks to encourage travel. As well at the time, orange groves during the citrus boom attracted many new settlers to Florida. By 1890, orange groves had become a status symbol for Florida as they provided a profitable and trustworthy crop that could be depended on. The search for the so called "Florida Dream" expanded in the 1920's and again after Second World War due to improvements to transportation and communication which made the state more attractive and accessible to tourists in particular. A new culture of beaches, architecture and commercial attraction showcased a lifestyle of leisure that was evolving into the modern Florida known today.

In the late 19th century, Florida hit its peak point, population began to grow rapidly, railroads were being built and the social scene began to develop. However this expansion slowed when Florida was hit by the beginning of the overwhelming suffrage caused by the Great Depression. Florida’s economy, up until that point had been booming with exports, tourism and new settlers. Inevitably, the banks, investors and people started running out of money and credit, and this lead to mass poverty throughout the U.S in 1929. Florida, in particular, was hit by hurricane after hurricane during the Depression and this certainly did not help the economy. In 1939, the Second World War began and this offered many jobs to those in poverty and eventually helped the U.S climb out of the depression.

After World War 2, Florida started becoming the state as we know it today. Florida went from once the least populated and developed state in the U.S to the South’s most populated state, and soon on to become the third most populated state in all of the United States. Much economic growth has consequently occurred in Florida since the 1940's due to the commercialization of leisure and vacations that has grown with the expansion of the advertising industry and the rise of a consumer-oriented society. Rising disposable incomes, increasing vacation times and the security of old age pensions have made the tourism and eventually retirement lifestyle possible. Florida's iconic nature expanded with a number of commercial attractions that began to spread around the state as these attraction have the potential to attract tourists from around the world. Much of Florida's growth during this era can be attributed to tourism becoming an increasingly modern experience. Since 1960, the tourist population itself in Florida over the average year, adds six to twelve percent to the states regular residents population. Florida would be an entirely different state had tourism entrepreneurs not spent so much on selling an escape land from the cold and a year round resort.

Florida's Modern Tourism Industry

[edit | edit source]Over the years, Florida has become one of the world’s most popular tourist destinations, from Walt Disney World to relaxing in Key West and Miami Beach. Florida's great beauty develops international attraction and is crucial in upholding the state’s booming economy which began in the late 19th century due to Northerners traveling south to “escape” the harsh winters. Florida’s economy now is widely supported by recreational and leisure travelers; many of the businesses located in Florida and the wildlife habitats rely on and support the needs of visitors. During the 20th century, Florida dedicated its territory to tourism, which would inevitably expand and prosper. To be successful, however, Florida had to sell itself as a place of civil rights quiescence, a land rejecting racial turmoil on the one hand and offer a stable climate for economic growth and lucrative tourism on the other. This is an intriguing part of Florida’s past as it conflicts with the mainstream values and widespread understanding of racial subcultures of the time.

Florida's increasing tourist development era most certainly aided in its rapid population boost between 1950 and 2000 as the state's initial population of 2.7 million increased six times. Florida, the fourth most populated state with its more than 18 million residents, is now an important cultural region of the United States due to travel and tourism. The desire for the "Florida Dream" with its tropical landscape of leisure has gained increased widespread appeal with the rise of a consumer culture at the turn of the twentieth century. Tourists are imperative to the financial state of Florida as they have accumulated 57 billion dollars into Florida's economy which is about ten percent of its gross state product. In 2005 for example, Visit Florida announced that the state had hosted a record 86 million visitors. Since the 1950's, Florida has truly become what its advocates has hoped for, exposure to the rest of the world and the armies of tourists that travel year round. Travel and tourism is integral to the understanding of Florida and its interesting and important history of development into its modern statehood.

Native American and Colonial “Florida," 1497-1821

Native American and Colonial “Florida,” 1497-1821

[edit | edit source]Introduction

[edit | edit source]

The written records of Florida begin in 1513, with the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon. The mass of land that he explored on the American continent would come to be named La Florida, in honour of Pascua Florida (Feast of Flowers), which is the name given to Spain’s Easter time celebration. By this time the Spanish had established Spanish hegemony in New Spain and much of the Caribbean. The Spanish soon considered Florida a vital asset in protecting the shipping routes they used to send bullion and other supplies back to Europe, especially since privateering was rampant at this time. With the French in Louisiana, Spanish colonization of Florida held the threat of cutting off their supplies routes to France. To the British, which had interests in the Caribbean and along the east coast, eventual colonization down the coast made conflict all but assured. Thus, Florida would become a focus for British, French, and Spanish colonization. This left many of the native tribes in Florida in a precarious position as they had to deal with the three imperial powers trying to establish dominance, each as likely to prosecute them for any multitude of reasons, but all resulting in exploitation. By the end of the 17th century most of the native tribes would be largely wiped out or nearly exterminated from disease and European aggression.

Pre-Seminole Indigenous Peoples of Florida (1497-1760)

[edit | edit source]The Calusa

[edit | edit source]The Calusa were an indigenous people of Southern Florida located in the southern regions of Florida, and are notable for being highly civilized compared to other tribes. Calusa societies were highly stratified, consisting of a sophisticated class hierarchy; from leader, elite, military class, ecclesiastic, to the common villager. This class based social system had benefits for upper classes comparable to similar class in Europe at the time. For example; leaders and elites had access to food otherwise restricted from lower classes and were exempt from physical labour. The Calusa also had a thoroughly developed complex spiritual belief system that clashed with ideals of colonial powers and missionaries. These cultural differences, specifically between the Spanish and the Calusa, ultimately manifested themselves in the form of Calusa resistance to Spanish Christianization and Hispanicization attempts. Regardless of aggressive actions, such as the Spanish missions in Calusa territory, this resistance was carried out in a largely peaceful way. However this peace would not last and after intensifying negative relations and acts of violence on behalf of the Spanish the peace between the two populations ended. After 1569 there would be no further significant contact between the two. The 18th century marked nearly two centuries of colonial expansion into Florida on behalf of the Spanish, French and later the British that brought diseases and colonial conflict to the region. The Calusa also faced slave raids by Creek Indians led by the British colonies in 1711. This combination of factors had effects not solely contained to the Calusa and meant that by the early 1700s Florida was essentially depleted of an Indigenous presence and the Calusa had become an extinct indigenous people.

The Timucua

[edit | edit source]

The Timucua were an indigenous people native to the Florida Peninsula that occupied the northern central regions from the eastern Atlantic coast to the most easterly areas of the Florida Panhandle in the west.The Timucua population consisted of politically divided chiefdoms only truly unified by language and their subsistence strategies via hunting. Like the Calusa, the Timucua territory also had a Spanish mission that was ultimately abandoned in 1706. However, unlike The Calusa, The Timucua had primary colonial relations with the French that were for the most part were largely peaceful and successful trade networks. The French employed a strategy of “allurement” meant to be more appealing than the sexual violence, rape and slavery that had become customary of the Spanish further south in the Caribbean. Ultimately, the French hoped to convert The Timucua to Protestantism, similar to the Catholicization the Spanish attempted with the Calusa. The Timucua refused, but in the end succumbed to the same fate as their southern neighbours. Colonial slavery raids, warfare, acculturation and relocation by colonial powers and later arriving Creeks pushed The Timucua out of Florida and eventually to extinction.

The Apalachee

[edit | edit source]

The Apalachee were an indigenous population residing in the Eastern regions of the Florida Panhandle bordering the western edge of Timucua territory. One of the three major tribes of the Pre-Seminole era (Apalachee, Timucua, Calusa) the Apalachee were the most “settled” of the three, having well defined boundaries, a material culture surrounding ceramics, cultivation of maize, and social norms surrounding the protection of women and children. Like their southeastern neighbours; the Timucua and Calusa, the Apalachee also housed a major Spanish mission within their territory at Pensacola, as well as the Spanish mission San Luis established in 1663 in the easterly regions of the Apalachee Province of the Florida Panhandle. The Apalachee's regionally specific allegiances and interactions with colonial powers had varying cultural implications resulting in three distinct Apalachee groups; French in Mobile, British in northern Creek territories, and Spanish in Tallahassee. The Apalachee were also the most successful of the three major indigenous tribes regarding sustained, successful economic relationships with the colonial powers; maintaining extensive relations with the French, Spanish, and British. However, like the Calusa these peaceful economic relations would not last due to increasingly restrictive trade regulations and increased Apalachee draft labour by the Spanish, as well as indigenous fear of the British's economic strength. Like the other indigenous people of Florida, raids from Creek Territories led to the relocation and eviction of the Apalachee to St. Augustine and Mobile in 1704. However, throughout the colonial Pre-Seminole era, the Apalachee more than any other indigenous tribe made the colonial economic system work in their favor.

Origins of the Seminole People (1760)

[edit | edit source]The Seminole Tribe of Florida as they are known in their contemporary context were not an indigenous people to the area that is now the state of Florida. Rather the Indians that came to be commonly known to Europeans and identify themselves as the Seminoles were a migrated or fragmented population of Creek Indians from Lower and Upper Creek territory in Georgia and Alabama. After the decimation of the indigenous populations of Florida through disease brought via colonization as well as conflict with European forces and European sponsored indian raids into vast expanses of territory remained largely uninhabited. This represented an amble opportunity for southern expansion into current day Florida by Lower and Upper Creek Indians. These Creeks were drawn into Florida not only due to the ample abundance of land, but also by prospects of trade with Spanish colonies in Latin America by way of The Gulf of Mexico as well as increasing pressures from British and later American southern expansion. As progressively increasing numbers of Creeks expanded into Florida and became separated from the Creek heartland along the Chattahoochee River in Georgia and this satellite population subsequently began to develop their own distinct culture that varied from that of traditional Creek Indians and thus these people became known as Seminoles.

European Interactions in Florida (1497-1821)

[edit | edit source]The Spanish in Florida

[edit | edit source]

There are two periods of Spanish rule in Florida. The first begins after Ponche de Leon first makes landfall in 1513 and continues until 1763 when the Spanish cede Florida to the British. The second is from 1783-1821, where the Spanish would reacquire Florida from the British, only to give it up 40 years later to the United States. Much of Spanish colonization and exploration, while sanctified and supported by the King, was a purely private matter. Much of the expenses for this process was paid out of pocket by the individual. Such an individual was called an Adelantado, and in exchange for funding his missions he was given great judicial and governmental powers over the lands that he took. This paved the way for the mass exploitation of the land, and the natives, for the sake of profit. The man who sought to bring this system to Florida was Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. After eliminating the threat that French colonization held within Florida at the battle for Fort Carolina, word of the massacre that occurred would spread to many of the native tribes. To their eyes, their only options were to submit to the Spanish or to die. The reputation Pedro established from the massacre inspired many tribes to submit. This submission meant accepting catholic missions and openly converting to the faith. Lordship over the Indians was a combination of suppression and gift giving; seeking to maintain alliances with the natives where possible, and crushing any rebellions when they arose. Spain’s power in Florida would not begin to be questioned after this until the 1700’s, and would even temporarily lose control of Florida from 1763 – 1783.

The French in Florida

[edit | edit source]

French settlement of Florida began in 1562, by a group of Huguenots (French Protestants). They would establish the colony of Mobile in the western most region of the Florida Panhandle in close proximity to the Spanish settlement of Pensacola. While the Huguenots would be expelled from Florida in a few short years, one of the gravest concerns to Spanish aspirations was that the French would manage to root themselves in Florida by establishing connections with the indigenous populations. They had already begun this process, but were soon defeated by the Spanish. The tribes that did ally with the French, by the time Pedro Menendez conquered Fort Carolina, would finally submit to the Spanish. The importance of the French colonization efforts in Florida, however, comes from the images created by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues, which are the earliest known visual representations of Florida and its indigenous people. While these images provide some knowledge about Native culture, specifically of the Timucua, they demonstrate greater insight into the aspirations of the French and their efforts to colonize Florida, and generally the perspective of the other European states.

The British in Florida

[edit | edit source]Florida was ceded to the British in 1763 after the Treaty of Paris at the end of the Seven Years’ War. While British rule in Florida would only last until 1783, a mere twenty years before it was given back to Spain, they still tried to do much. Florida under their rule was divided into an east and a west. Similar to the Spanish system, the British during their occupation gave constant gifts to the Indians in an attempt to keep the peace. While the cost of this was high, it was seen to be much less than the cost of war. Of the natives that the British were courting, the most important were the Creek, later commonly known in Florida as Seminoles. In the 17th Century some Upper and Lower Creek populations in fact allied with the British colonies to the north. These loose colonial indigenous alliances had a profound impact on the indigenous populations further south in Florida. British colonialists "employed" most typically Lower Creek Indians to raid indigenous settlements throughout Florida in hopes of weakening rival colonial interests of the French and Spanish in the region by destroying their network of allegiances with the indigenous populations. Eventually these raids coupled with foreign diseases brought by European colonists resulted in a vastly diminished indigenous population in Florida as many either died or were pushed out of the territory due to these raids. These Creek Indians eventually migrated south into Florida due to intensified British colonial expansion into Northern Georgia and vast uninhabited lands to the south in Florida due to the devastation of indigenous tribes. Here these Creeks became disconnected from the heartland of the Chattahoochee River in Georgia and developed a distinct culture that led to their branding as the Seminoles by European colonials.

The War of 1812

[edit | edit source]In 1794, the Thermidorian Revolt expanded across France as a consequential result of leader Maximilien Robespierre’s reign of terror. Robespierre suffered his execution at the hand of Thermidorian rebels as they permanently acted to end the systematic state oppression they for so long endured. Napoleon Bonaparte became the new successor of France, and he hastily began to lead the nation into an 11 year period of continuous war. In 1806, Napoleon implemented a new policy called the Continental System. The goal of this system was to act as a blockade in protecting French manufacturers across all European markets. Correspondingly, the British reacted to this new implementation by cutting off all French commerce from Atlantic markets. In their perspective, anyone who continued to conduct trade with France would from then on, be considered an enemy of Britain. The neutrality of America in the Napoleonic wars would not last for long, as their ships were soon ransacked, and both their goods and men, were taken into British custody for their continual efforts to trade with France. Finally on June 18th 1812, American president James Madison declared war on Britain. Simultaneously, as war was waging overseas, American officials were expanding their territories by tricking Indians into signing treaties that handed away millions of acres of land to the United States. Conclusively, this act would lead to the cooperation of both Britain and Spain with the American Indians as a united force in stopping the United States expansion.

Natives and the War

[edit | edit source]On October 3, 1783, The American Revolutionary War ended with the Treaty of Paris which ceded the lands of Florida over to Spanish control. In 1811, the Americans permanently demanded that the Creeks allow a north-south road to pass through their lands to connect white settlements on the Tennessee River with Fort Stoddert. This was the situation that brought forth the Shawnee chief Tecumseh, into action by uniting Indian tribes through the common goal of protecting their lands against American expansion. Both Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet, realized what few other Indians ever saw: only if all tribes made common cause could they hope to contain the United States as it exploded out of its borders. Tecumseh’s efforts aroused the Creek and Seminole Indians to join together in war against the United States. At this time, Indian forces were limited to fewer technological advances and supplies than their opponent, and they thus began seeking more powerful allies to join their cause.

1812 and 1813 were critical times in the Gulf Coast area and in Florida for both Spain and Britain. The United States had begun to infringe upon, and disrupt Spanish owned territory. To secure his country’s possessions from further aggression, the Spanish governor Sebastian Kindelon incited the Seminoles and the Negros against the American interlopers in 1812. Simultaneously, Britain had gained powerful Indian allies through their mutual desire of halting U.S expansion, and were willing to provide arms, troops, and training to the Indian and negro forces. Both Spain and Britain began cooperative measures in the hopes of successfully stopping the United States. Over the course of 1814 and into 1815, Colonel Edward Nicolls of the Royal Marine, and George Woodbine, a white trader from the slave and Indian populations of the Southeastern borderlands, worked together in raising minority forces against the United States. Nicolls and Woodbine erected a fort on the Apalachicola River in West Florida and between August and November of 1814, they occupied the capital of Spanish West Florida, Pensacola. Britain utilized the efforts of blacks and Indians, in it’s war planning, for they aspired to exploit southern feats, thereby distracting the southern war effort and inspiring local, able-bodied recruits to join the effort.

After a series of small-scale battles that shifted in success between both sides, the war had finally reached its endpoint. American general Andrew Jackson offered an “ultimatum” to the Spanish governor, for him to expel the Indians and blacks from Spanish territory and to stop Britain’s use of Pensacola as their base. Jackson’s offer was declined, and shortly after on November 6th, he arrived at Pensacola with his army in tow. Upon their arrival, American troops were faced with almost no resistance from the Spanish residents of the town.

The British had taken refuge at Fort Barrancas, located at the mouth of the harbour. As the situation became hopeless, they decided to board the British fleet anchored in the bay, blow up for Barrancas, and retreat to the fort on the Apalachicola river. In the ensuing chaos, British forces, their Indian allies, nearly the entire slave population of Pensacola, and over two hundred Spanish troops evacuated the town. America had conquered the Gulf of Mexico as their own, and with it came the destruction of Indian relations with Britain and Spain.

Britain and the War

[edit | edit source]In 1783 the British Empire lost their territory in Florida to the Spanish. Through this conflict, the British and Spanish rivalry allowed for the United States to be relieved of either of the empires full aggression. However, by 1812, the United States was a far larger threat to Spanish Florida than Britain. The chaos in Europe caused by the Napoleonic wars made it possible for multiple intrusions into Spanish Florida by the United States. The Spanish, as a means to reinforce their loose hold on the Florida territory, supported the Seminole Indians so they would serve as a barrier between them and the United States. As such the Spanish gifted weapons, munitions and supplies to the Seminoles to maintain their strength as well as a peace with the United States.

The war with Britain in 1812 led to unusual tactics by the British to rouse opposition inside Florida. For instance, in Pensacola one British Naval Officer saw the military potential of bringing slaves to the side of the British war effort. Pursuing the tensions he perceived inside the slave society of the U.S. he formed a troop of soldiers of over 200 former slaves fighting with the British. Though the success of the troop was limited, the willingness to fight against slavery alongside the British can be observed as a precursor to the further escalating tensions of slavery during the Civil War.

Florida and the War

[edit | edit source]The history of Florida during the War of 1812 necessarily involves conflicts with native tribes and the Spanish. The area of what is today Florida consisted of Spanish controlled Florida West and East. The conflicts in these regions were characterized by American attempts to forcibly control them. This was not direct warfare with the Spanish, instead it took the form of conflict with Spanish backed Native tribes and a combination of British and Creek forces. As such, native tribes were central allies to all conflicts in Florida. The Seminole, Creek and slaves were seen as an important alliances by both the Spanish and the British, though for different reasons. The Spanish feared that the U.S. was going to annex Florida. Therefore the Spanish strayed from their usual policy of keeping the Seminole as a potential defensive force to increasing their amount of military aid to construct heavily defensible forts. The British during the war saw the same groups as a means to divert attention away from Upper Canada: the focal point of U.S. aggression in the War of 1812. The Seminole and Creek desired to stop the white settlement they regarded as most harmful to their people. They saw the British and Spanish as allies against the United States, so they accepted their aid.

Florida in this period contained precursors of the fast, broad and violent expansion of the territory of the United States across the American continent, which often happened outside federal government jurisdiction. Between 1811 and 1814 bands of settlers, soldiers and militias attempted to invade East Florida in the hopes of expelling the Seminoles and Spanish there. The eventual ceding of Florida to the United States by Spain in 1819 was done in the light of this aggression and a knowledge inside the United States that Congress may declare war on Spain. The prevailing political rhetoric of the era was that the precarious territory of New Orleans and Florida would fall into British control, and the War of 1812 was in part justified by this proposed danger to the new nation. Indeed, all territory controlled by the British in North America was seen as a potential threat, so in this manner Florida is not particularly unique: it was subject to the same kind of policies as other territory like Canada and the North American west.

The Outcome of the War

[edit | edit source]There were contrasting assessments of the war made by the federal government. Some praised the divine providence of the American people in their victory, others more rationally weighed the noticeable victories and failures of the war. A particularly espoused victory was the abandonment of the British naval campaign against the United States which included damaging blockades- which were especially prominent in Florida. The views on the purpose of the war varied greatly. Many argued that it was entirely a war of conquest, done for mere power and territory. This is reflected in the personal records of American soldiers, who rarely recorded their reasons for fighting as beyond a sense of duty or for the money. The outcome of the War of 1812 for the Red Stick Creek was an expulsion from their homeland. Following a defeat at Horseshoe Bend in 1814, Andrew Jackson forced their capitulation with the Treaty of Fort Jackson on August 9th. The treaty ceded 35 million acres of land in modern Georgia and Alabama from the Creek natives and placed it into the control of the United States, and forced the Creek to flee below the border to Florida where they would join the Seminole tribes. The Creek and Seminole tribes would never fully accept the treaty and simply viewed the coming American settlers as intruders on their land. The support of the Spanish was continued after the end of the war in 1815 in order to maintain Spanish control, but was largely done outside Spanish officials knowledge and therefore often lacked adequate resources. The end of the War of 1812 also served to further establish an “American line”- a frontier boundary within Florida between the coalition of native tribes and the United States. In this manner, the Seminole maintained a semi-autonomous state under the Spanish, but it didn't last for long. Under the pretext of Seminole aggression towards the "invaders" of their land, American settlers, militias and soldiers would fight continual skirmishes along the frontier. This frontier territory set the stage for treaties, wars, the ceding of Florida by Spain and the eventual deportation of the Seminole.

The First Seminole War

[edit | edit source]Origins of the War

[edit | edit source]

The War of 1812 had concluded with unrest in the United States. During the war the British had built a fort on the Apalachicola River. In 1816 it was primarily garrisoned by roughly 350 former slaves, thus granting it the nickname of the "Negro Fort". Many southern plantation owners, including Andrew Jackson, considered these former slaves to be renegades and a menace to society, they were afraid that the ex-slaves were going to ruin the innocence of “white woman-hood and the security of the plantation south”. Later that year, in an attempt to bring order to the region, the United States built Fort Scott just north of the Spanish border. Jackson presented the Spanish commander at Pensacola with an ultimatum, either Spain would dismantle the fort or the United States would have to eliminate the fort in self-defense. In actuality, Spain did not have the manpower to perform the task, so it fell to the Americans. The plan for destroying the Fort involved sending gunboat-accompanied supply boats to Fort Scott, which was further in-land on the Apalachicola. This was done in the hopes of provoking the Fort into attacking the boats, giving the United States reason to attack the Fort. The plan worked, and on July 27, 1816 a red-hot cannonball fired from an American gunboat struck the major powder magazine and obliterated the fort. Thus the Negro power on the Apalachicola had broken, and the Seminoles grew weaker. In retaliation for the destruction of the Negro fort, Hitchi chief Neamathla ambushed a US army boat close to Fort Scott, killing thirty-four US soldiers. This infuriated the US, and after Neamathla sent a warning to Colonel David Twiggs: "not to cross or cut a stick of timber on the east side of the Flint." Twiggs led an army of 250 men to capture the Hitchiti chief, resulting in a firefight that killed five Seminoles. However, when Neamathla escaped, Twiggs burned down Neamathla's town, marking the beginning of the First Seminole War. Neamathla's actions set the precedent for guerrilla conflicts along the border, and led to increased border skirmishes during the summer of 1817.

The War and Imperial Relations

[edit | edit source]

The First Seminole War was a violent conflict in Western Florida from 1817-1819, encompassing conflicts between The United States and the Seminole Nation. The Seminoles were formed from Native American tribes that had migrated down from the north and banded together. Some of this migrating due to conflicts such as the War of 1812. Additionally, escaped African American slaves found a home among the Seminoles. Together they raided white American settlements across the border into Georgia and Alabama, killing inhabitants and stealing their property out of Revenge for the Treaty of Fort Jackson. When complete, these native raiders would simply flee back across the border into Florida, away from the Jurisdiction of the Americans. Spain could not control these borders, which forced the United States to take action. Andrew Jackson, commander of the southern military district, led the controversial advance into Florida, devastating the opposition. In the future this order would be controversial; members of congress would later claim that the invasion was unconstitutional, as the legislature and executive branches of the US were not consulted. The conflicts raised tensions between the United States with Great Britain and Spain.

On December 26, 1817 secretary of war, John C. Calhoun, ordered Jackson to enter Florida: "with full power to conduct the war as he may think best", knowing that if given the chance, Jackson would take Florida from Spain. Jackson left in haste soon after his arrival at Fort Scott on March 9, 1818 with an army of 3,300 primarily Tennesean and Georgian militia. On April 1st he moved in on the largest Seminole town of Miccosukee alongside William McIntosh; a half creek who had grown vengeful due to large property losses at the hands of the Red Sticks. There was a rift in the creek confederation, and many creeks stood by the United States. McIntosh lead an army of Creek Indians who would support Jackson in his attack, and together they took Miccosukee with little resistance. There were no signs of withdrawal, and Spanish town of St. Marks was taken five days later. Here the Scottish, Seminole sympathizer; Alexander Arbuthnot, was captured and would eventually bring controversy upon Jackson's campaign.

Jackson’s next target was Seminole chief Bowleg’s Town of Suwanee on the Suwanee River. Here McIntosh's army encountered the main Seminole force and a firefight ensued resulting in the Seminole forces being routed. The army continued at full pace trying to prevent the Seminole inhabitants of Suwanee from crossing the river. However word quickly spread and Suwanee began to evacuate in order to escape the onslaught. Later on in the day they attacked and quickly forced the remaining Seminoles to retreat. Jackson ordered the town to be destroyed, and in the process they captured Robert Ambrister, another Englishman who provided the Seminoles with weapons, and other supplies. Jackson, upon capturing a second British agent in Florida, confirmed his own suspicions of British involvement in the Native aggression towards the U.S. Jackson ordered Ambrister and Arbuthnot to be executed due to the allegations of aiding the Seminoles against the US. These executions would lead to an increased potential for conflict with Great Britain.

After the rout at Suwanee, Jackson quickly learned that 500 hostile Indians had gathered near Pensacola, the main Spanish settlement in West Florida. Jackson marched his army 240 miles to Pensacola which he occupied on May 24th without resistance. There was now only one Spanish center on the peninsula however the assigned task was now complete. The Seminole fighting force had broken west of the Suwanee River and was forced to disperse. Some forces fled to the Alachua area, however many withdrew to Tampa Bay and the lakes of North Central Florida. The Floridian Peninsula was now firmly under the control of the United States.

After the War

[edit | edit source]Although the United States coveted Florida, the executions of Arbuthnot and Ambrister had enraged Great Britain, and they didn’t want to risk Great Britain aligning with Spain in a possible war. Therefore the United States returned St. Marks and Pensacola to Spain despite Jackson's protest. However, recognizing that it had only taken Andrew Jackson eight weeks to conquer Florida, Spain realized that they could hope to maintain control of the Peninsula. They ceded the Florida to the US on February 22, 1819, in a treaty that would be finalized after two years time, and its conqueror; Andrew Jackson, would become its first governor. The First Seminole War had opened a period of population growth and economic gain for the United States. They would continue to prosper and expand for years to come.

Further Reading

[edit | edit source]Granberry, Julian. The Calusa Linguistic and Cultural Origins and Relationships. (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2011): Johnson, Patrick Lee “Apalachee Identity on the Gulf Coast Frontier.” Native South 6 (2013).

Martel, Heathere. “Timucua in deer clothing: friendship, resistance, and Protestant identity in sixteenth-century Florida.” Atlantic Studies 10 (2013).

Stojanowski, Christopher. “Unhappy trails: forensic examination of ancient remains sheds new light on the emergence of Florida's Seminole Indians.” Nature History 114, No. 6 (2005).

Widmer, Randolph J. “The Rise, Fall, and Transformation of Native American Cultures in the Southeastern United States.” Reviews in Anthropology 39, no. 2 (2010).

Antebellum Florida: Territory to Statehood, 1821-1861

Slavery in Florida, 1821-1861

[edit | edit source]The Beginning of a Slave-Based Economy

[edit | edit source]

Under Spanish rule, slavery played a minimal role in Florida’s economy and culture. Much of the free Black population in Florida resided in St. Augustine at this time, where it was not uncommon to find black people who owned both rural land and slaves of their own. When Florida was eventually ceded to the British, the dwindling free black population remained in St. Augustine. The role of slavery drastically changed under British rule, and Florida saw a dramatic increase in institutionalized slavery. The Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819 signified the sale of Florida to the United States, and in 1821 the flag was officially handed over to Andrew Jackson and his men, thus making him the first military governor of Florida. Though Florida was now in American hands, British rule had left a lasting impact on slavery within the state. With abundant frontier now available, Americans began to take note of the economic potential that lay to the South. The slave trade in Florida was mainly concentrated in the heart of the “Cotton Belt,” which included cities such as Tallahassee, Jackson and Jefferson. In 1821, only a small percentage of wealthy white planters, a few free blacks in Eastern Florida and holdovers from the Spanish era owned slaves. When the transatlantic slave trade was abolished, Florida saw a rise in the domestic slave trade. The average number of slaves owned by a single planter had almost doubled now, as people began to fully exploit the growing fiscal worth of slaves. Slavery was a highly profitable business, and was therefore an important aspect of Florida’s economy. The necessity of slavery as a part of the economy was due to the fact that they were viewed as property, could be used as collateral for loans, act as extensions of credit and even be lent out to earn supplementary income for their owners. It was not uncommon for slaves to be hired out to perform jobs such as construction, roadwork and domestic work. During the 1830’s, Florida’s economy had almost completely shifted to farms and plantations based solely on slave labour. Florida’s expansion in its territorial era was chiefly rooted in a slavery-based farming and plantation economy, which drew political and social elites from prominent slave-owning planter families of the old South to Florida. Florida further prospered through trading along its expansive coastline, which allowed for easy export of cotton to many European destinations. By 1845, slavery had become a firmly established component of Florida’s culture and economy.

Solidifying the Institution of Slavery

[edit | edit source]

The institution of slavery played such a pivotal role in the economy that many government policies were being instituted specifically to solidify its place in the state. One way this was achieved was by separating slaves and free black people into their own distinct legal category as a way to keep the laws that govern white and black people separate. In 1827 provisions to the statutory law restricted implementation of the emancipation of slaves, and included the denial of free black people into the state in order to promote the expansion of slavery in Florida. By 1842 free blacks already in Florida were required to concede themselves to a white guardian or face persecution. Laws that prohibited the restriction of slave importation into the state were also included within these articles. The growing fear of abolitionism prompted the extreme oppression of black people through the further stringency of slave legislation. This also resulted in laws controlling the interactions between white and black people. Assisting a slave in escaping or being found guilty of stealing another man’s slave were considered crimes punishable by death. A Spanish plantation owner by the name of Zephaniah Kingsley, disagreed with the American attempt to segregate and reduce the free black population from the rest of Florida. He believed that Slavery would function best under the control of white elites along with the support of free blacks as the two groups would be able to better control a larger amount of slaves and eventually create a more prosperous system of slavery. Many other Spanish planters who had remained in Florida after 1821 agreed with his idea of a more humane brand of slavery, however their voices were muzzled by the rest of Florida's white population.

Slave Codes

[edit | edit source]The full equality of citizen’s delegitimized Florida’s slave based economy, and as a result legislations known as the Slave Codes were implemented. The Slave Codes maintained the subordination of slaves and implemented control over the race as a whole. The Slave Codes were also a way to preserve the economy, political hegemony and the status of white people within Florida . The intent of this oppressive legislation was to restrict freedoms such as the ability to communicate by prohibiting all slaves from learning to read or write. The codes also outlined that no slave could congregate without the supervision of a white man, nor could they possess weapons or property. They also sanctioned barbaric punishments such as branding, mutilation and corporal punishment if a slave were to disobey their owner. The preferred form of punishment by slave owners was the use of a whip, as it was able to inflict pain without leaving lasting scars, which would decrease the worth of one’s slave. These laws also acted as a way to protect the white population from insurrection, which was a growing fear due to the increase of Northern abolitionism. These codes provided the state the ability to clarify the status of a slave in society while stabilizing the hierarchy that existed in Florida during this time.

Native Relations in Antebellum Florida

[edit | edit source]A Strained Relationship

[edit | edit source]Americans quickly made preparations to subvert the resident Native population, the Seminoles, following the ceding of Florida to the United States in 1821. Animosity pervaded relations on both sides, stemming from the First Seminole War in 1817 and an increasing American presence near Indian lands. The Seminoles who were once a vast network of independent tribes, had already withered in the face of American expansion. In the years leading up to the Second Seminole War, they endeavoured to protect what land they still possessed.

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek (1823)

[edit | edit source]Officials in Washington had long deliberated the issue posed by the Native population occupying their new territory. In 1821, Secretory of War John C. Calhoun proposed that the Seminoles either be concentrated into a single area within Florida, or removed from the territory completely. It quickly became clear which of these the American settlers favoured, and a plan was soon drafted to remove the Seminoles to a Creek reservation out of state. However, this idea was rejected wholly by the Seminoles due to difficult relations between the two Native groups. The government ultimately decided to collect and settle them within Florida, and called a gathering in September of 1823 at Moultrie Creek. The four hundred Seminoles who attended were represented by a Mikasuki-band chief, Neamathla. Commissioner James Gadsden led the representatives of the United States. The resulting Treaty of Moultrie Creek stated that all Seminoles would move to a four million acre reservation in the centre of Florida. They were to renounce all claims to their former territory, and would receive payments, including a monetary payment of five thousand dollars per year for twenty years.

Native Conditions Deteriorate (1823-1830)

[edit | edit source]It took two years for the Seminoles to relocate to their new territory. Meanwhile, settlers continued their aggressive push inwards towards more fertile lands, which increasingly brought them into contact with the Natives and their new reservation. The situation deteriorated through the decade, as each side complained of theft and trespassing by the other. Settlers would cross onto the reservation to capture escaped slaves who had come to reside there. In 1825, a drought resulting in poor crop yields near the end of the decade left a large portion of the Seminole community impoverished and starving. Famished, many resorted to foraging and theft across reservation lines. These episodes often ended in injury or death, as was the case in an incident in 1829 which ended in the deaths of two natives and the theft of their equipment. Meanwhile, pressures continued to expand as Florida residents across the land advanced their petitions for total Indian removal from America's new territory.

The Indian Removal Act (1830)

[edit | edit source]The fate of the Seminoles would not be a matter of debate for much longer. Andrew Jackson, a former governor who had long advocated for Indian relocation, was elected President in 1830. Soon after his election, he pushed for Seminole removal from Florida. On May 28, 1830, congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which allowed for the president to negotiate with the Seminoles for their removal to lands west of the Mississippi River. James Gadsden, who had negotiated the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, was again sent to negotiate on behalf of the government.

The Bad and the Ugly: The Treaties of Payne’s Landing (1832) and Fort Gibson (1833)

[edit | edit source]Starvation and hardship continued to plague the Seminoles through the early 1830’s. They were in a desperately poor position to negotiate when James Gadsden arrived in early 1832. Fifteen chiefs assembled with Gadsden and signed the Treaty of Payne’s Landing in 1832, which stated that they were to move to land set aside for them west of the Mississippi. This was conditional upon a favourable inspection by a party of their own representatives. Unfortunately, a detailed record of the meeting was not made, leading to speculation about the treaty's legitimacy. Nevertheless, a delegation of seven natives was sent to inspect the land in October of 1832. Upon completion, they signed the Treaty of Fort Gibson on March 28, 1833, which signified their approval of the land. Both of these treaties were called into question soon after being signed. The chiefs who had signed the documents either denied that they had done so, or protested of coercion. Further, Natives back in Florida claimed not to be bound by these treaties. The government, meanwhile, quickly ratified these documents and set a three year deadline for Indian removal. It was becoming increasingly clear that the Seminoles would not move out of Florida willingly. An outbreak of war soon seemed inevitable.

The Second Seminole War (1835-1842)

[edit | edit source]

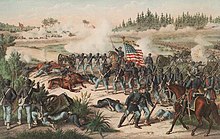

The Seminole Wars were a series of conflicts fought between the United States military and the Seminoles; a Native American tribe originally from Florida. The conflict consisted of three distinct wars which were all fought largely over land disputes between the federal government and the Seminoles living in Florida. The Second Seminole war (1835-1842) is regarded by historians as the most brutal and costly war waged between the federal government and Native Americans. The second Seminole war was a result of the Dade massacre.

The Initiation of the War

[edit | edit source]The second Seminole war was initially prompted when President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830 which mandated all Native American tribes residing Florida be moved inland to Indian Territory in Oklahoma, permitting the use of military force if necessary. Initially most of the tribes moved with little resistance, however the Seminoles resisted this forced migration. Among the Seminole leaders resisting the Americans was a young, brave warrior by the name of Osceola. When non-violent protest against native relocation failed in 1835, over 5,000 Seminoles retreated into the swamps of the Florida everglades. By autumn of 1835, violence had broken out across Florida. Disillusioned and embittered by weak leadership, younger and bolder leaders emerged among the Natives. The Seminoles were a distinguished and feared guerrilla fighting force, one that Andrew Jackson had already fought against when he attempted to drive them out of the Floridian peninsula in 1817.

Allied with the Seminoles were many free African Americans, those whom had fled captivity and brutality at the hands of American settlers. Seeking a new life, many had been welcomed and integrated into Seminole community, a deed which further provoked the Americans. Two subsequent treaties did little to alleviate the situation and instead gave an outlet for hostilities to begin. In December, a Seminole force killed several high ranking officials on the outskirts of Fort King. On the same day, Major Dade and two companies of soldiers were ambushed in Sumter County, and all but three were massacred. The war had begun.

The Dade Massacre

[edit | edit source]In December of 1835 a number of Seminole ambushes resulted in heavy American casualties. The Dade massacre was one such incident of devious Seminole tactics. Major Francis L. Dade was traveling with a company of roughly 110 men from Fort Brooke to Fort King to provide military support against the Seminole threat. Dade and his men were ambushed by a group of Seminoles, killing all but a handful of American Soldiers. Days later on New Year’s Eve Osceola and a band of 250 Seminole warriors defeated a company of 700 soldiers under the command of General Duncan Clinch on the banks of the Withlacoochee River. Despite suffering few casualties, Clinch was forced to retreat and was soon replaced by General Winfield Scott. General Scott was regarded highly for his military prowess as well as his heroics in the war of 1812. However, Scott’s expertise was in conventional “gentlemanly” warfare; he was horribly unprepared for the guerilla warfare tactics employed by the Seminoles. The Second Seminole war lasted a gruelling 7 years and was in general regarded as a tremendous failure on the part of the United States military. American author Michael Grunwald regarded the Seminole war as “America’s first Vietnam – A guerilla war of attrition, fought on unfamiliar, unforgiving terrain, against an underestimated, highly motivated enemy who often retreated but never quit.” Public opinion surrounding the war was negative, congress wanted the war to be over, but feared forfeiting would make the federal government look weak and result in a domino effect of backlash from other tribes.

Concluding the War

[edit | edit source]In January of 1836, President Jackson appointed a new commander and sent fourteen companies to join the forces already within the territory. Vastly out-numbered, the Natives employed guerilla-style tactics to great effect. Skirmishes broiled across Florida through the next six years, as the United States drove out the Seminoles. Finally, Colonel Worth declared an end to the war on August 14, 1842. The seven years of conflict resulted in death or expulsion for a majority of the five thousand Seminoles who had once resided within Florida. A small force remaining was allowed to occupy a temporary reserve at the mouth of the Peace River. In contrast, at the peak of the conflict in 1837 a force of 8866 troops had been deployed by the United States, and 1466 had lost their lives. Estimates place the cost of the war as high as forty million dollars, solidifying the Second Seminole War as the costliest war of Native removal in American History. The settlers were left with a ravaged frontier, destroyed homes, and a depression. Yet, they had triumphed and claimed their new land, leaving the Seminoles broken and defeated.

Battle Conditions

[edit | edit source]The conditions on the battlefield were atrocious to say the least. The everglades proved to be treacherous to navigate by foot and impossible to navigate from horseback. Soldiers had to carry supplies through dense swamps and mangrove forests, meanwhile keeping an eye out for Alligators, Snakes and ambushes from the Seminoles. Mosquitoes also posed a massive problem for American soldiers. Unbeknownst to the Americans at the time, mosquitoes were not just a buzzing nuisance, but also vectors for diseases such as Dengue fever and malaria which caused more casualties than fighting with the Seminoles did.

Florida from Civil War to the Gilded Age, 1861-1900

Civil War and Reconstruction in Florida

[edit | edit source]Florida seceded from the United States on January 10th, 1861 becoming the third state to do so and was admitted to the Confederacy on February 4th, 1861. Secession to most Floridians was legal, logical and justified. J.E. Johns describes how the majority hailed the creation of the Confederacy as a permanent respite from the sectional controversies which had plagued the people of the United States prior to 1860.

The success of the secession movement in Florida was the result of events within the nation and the state between 1850 and 1860. Settlers had been flooding into the state during this time, mostly from Georgia and South Carolina. These settlers brought their traditions and state-rights philosophy. By the late 1850s, the Democratic Party – the fiercest defender of states’ rights and slavery – was the only true national party and was dominant in Florida, helped by popular anti-Republican Party sentiment within the state. When the Republican Party won the presidential election in 1860 with its anti-slavery position and heavily northern tinge, Florida quickly seceded.

The Civil War

[edit | edit source]During the Civil War Florida suffered economic hardship, naval blockade, internal dissension, Union invasion and defeat. Its main contribution to the war was not in the form of troops, but supplies. Florida was geographically vulnerable and was incapable of defending itself from union raids, naval blockades which consequentially compromised its methods of resupply. The State of Florida has a unique history that is easily distinguishable from other confederate states as it shared different geographical challenges, constructed and dissolved treaties with Florida natives and underwent significant African American recruitment to the union. General Winfield Scott pressed the importance in executing a naval blockade in the Mississippi River and around the coasts that would evidently isolate the confederates and eliminate any potential routes of foreign aid/ resupply.

Fort Pickens was the location of one of the earliest confrontations Florida faced with the Union and was to be one of the few southern forts to remain in Union hands throughout the Civil War. Other battles in Florida include, the Battle of Fort Meyers, Battle of Fort Brooke, Battle of Marrianna, Battle of Natural Bridge, Battle of Olustee, Battle of Saint John's Bluff, Battle of Santa Rosa Island, Battle of Tampa, and Battle of Gainesville. It was in September 1861 that the first bloodshed in Florida occurred when the Federal warship named Colorado came into contact with the Confederate vessel Juda near Fort Pickens. Union soldiers drove the Confederates from the vessel before setting fire to the ship. The first action by a Confederate force in Florida came as a result but failed to destroy or capture the fort.

The Confederate State of Florida found herself in a unique situation as it was tasked with providing able men to the confederacy as well as desperately defend its coast from Union raids and naval blockades. Florida’s efforts to provide its share of military contribution while securing its own territories resulted in failure in 1862 as the federalist troops successfully secured Fernandina and St. Augustine without much resistance and established numerous military bases along the coast. Union Maj. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore had a firm foothold in Florida. He was famously credited for recruiting black troops in Florida and cutting off all confederate sources of resupply from and to the state.

Florida was a crucial factor for the South in the civil war in terms of supplying food and troops. After seceding from the union and joining the confederate states Florida had supplied 5000 troops by the end of 1861. Since Florida was a southern state it meant they relied heavily on plantations and slave labour to boost their economy, similar to other confederate states. During the civil war one of the big downfalls of the confederate states was their lack of firepower, which is why conscription became law in Florida in 1862, in order to provide more support.

Before the fall of St. Augustine, Florida legislatures appointed John Griffin to travel to Southern Florida and form a mutual alliance with the Seminole Indian tribes against the union. The foundation of this relationship would be on supplying staples, trade and military protection under the confederacy. However when St. Augustine fell to the Union, Southern Florida became a haven for draft dodgers, white northern sympathizers and many still loyal to the confederacy became paranoid that the natives had joined the union cause.

During the Civil War Florida often came into conflict with the Confederate government, notably over the issue of supplies. The governor during the war, John Milton wrote to President Jefferson Davis to warn him that Florida citizens “have almost despaired of protection from the Confederate government”. The defense of Florida went from inadequate to almost non-existent during the course of the war and even led to some suggesting the abandonment of the state. In one example Pensacola, the largest city of West Florida, became a city of deserted homes. Despite experiencing heavy union military pressure, Florida remained part of the confederacy until after the war as union forces could only control only a few major cities. However what is more interesting about Florida is the decisive recruitment and accomplishments of African Americans in the union army. Florida had among the lowest blacks volunteer turnouts to join the union army, though surprisingly they were acknowledged as representing 44.6% of Union Florida regiments and most came from East Florida. They represented 10% of Florida’s black population and by the war’s end they represented 15% of the union navy. The very fact that Florida remained a confederate state during this time speaks loud words about the number of black volunteers

The largest battle that took place in Florida during the conflict was the Battle of Olustee, February 1864, a victory for the Confederate Forces. It marked a “bloody check to the Union cause in Florida” and forced the Federal troops in East Florida back to the three fortified towns which it occupied – Fernandina, Jacksonville and St Augustine. Although this was a major Confederate success, Florida had relatively little value militarily to the Union and it thus had little impact on the wider war which the Confederacy was to lose. What the Battle of Olustee did was spell defeat to hopes among Unionists that Florida would be returned to the Union before the wars end.

President Andrew Johnson declared the end of the Civil War on May 9th 1865. The war had taken a devastating toll on the seceding states with the conflict having spread over the Confederacy “like some hideous flood”. Florida was no exception and it bore its full part in the struggle with some 16,000 of its best citizens having gone to war, fighting in all of the major battles. At least 5,000 Floridian soldiers died. Destruction of property was great also – falling from a total worth of $47,000,000 to $25,000,000 during the course of the war.

Reconstruction

[edit | edit source]On July 25th 1868, after the state ratified amendments to the Constitution to abolish slavery and grant citizenship to former slaves, Florida was fully restored to the United States. The period after the Civil War is known as the Reconstruction period. The initial plan for reconstruction was moderate but as Davis argues, radical reconstruction was probably inevitable from the hour Lincoln was assassinated. One of the most prominent aspects of the Reconstruction period was the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency established in 1865 to aid freed slaves and it played a major part in the education of African-Americans in Florida after the Civil War.

Although Democrats initially controlled the Florida state government after the Civil War, the confederate states began to pass the infamous black codes. These laws, and legislature that passed them were described as “bigoted, vindictive and shortsighted" ultimately limiting the rights of African Americans and forcing them to work in a labour economy for low pay. Republicans in Congress suspended all Southern Governments and disfranchised all Confederate officers and elected officials, giving the party control of southern governments including that of Florida.

Racism continued to be enacted as policy. Former slaves were not permitted to testify in trials unless an all white jury had first determined that they were creditable or if a contract between a former slave, now a free worker and their employer was broken they could be sent to prison. The laws were an effort to make the society “separate but equal” however white offences were often overlooked or given small punishments. In one case a white man was charged with killing a freed slave and received a fine of $200 and one minute in prison.

Many of the recinstructionists in Florida were primarily focused on restoring the economy in the hope that a growing economy would help in the reconstruction process. The Freedman's Bureau also agreed that economic growth would help with reconstruction. Prior to the civil war and shortly after, Florida relied heavily on the cotton industry. Former slaves were encouraged to return to plantations and to continue to work there as share croppers. These sharecroppers were offered a percentage of what was produced. For the most part the former slaves never made enough to leave and would often buy personal items from the planation owners on credit, however they often did not make enough money to cover theses debts and would be unable to leave.

Florida’s economy underwent significant changes during Reconstruction. Before the war large plantations producing cotton with slave labour had been the most important aspect of the economy but this diminished in importance with the freeing of slaves as a result of the Civil War. Lumbering replaced much of this, becoming extensive in the state.

New industries emerged in Florida some of which included citrus, cotton, sugar and lumber among others. Slave labor was no longer an option for Plantation owners and instead had to hire African-Americans as employees although they were paid poorly. Their pay was so much lower than what a white man of the time would make that it discouraged European emigrants from moving to Florida due to an inability to compete for jobs.

In thirty years the state’s population tripled, growing from 140,424 in 1860 to 391,422 in 1890 due to increased opportunities and land development throughout the state. The massive population increase helped to bolster the workforce of the various plantations and farms as agriculture took root as one of the dominant industries of the state. By 1866 nine-tenths of Florida’s African American population were working in agriculture.

Although Florida saw economic growth after the end of the Civil War, the government had accumulated debt which threatened to bankrupt the state, thus leading to the sale of four million acres of land to Hamilton Disston ‘and associates’ for one million dollars in 1881. Intensive land development in Florida began following the purchase and new development programs were launched by Railroad companies in an attempt to encourage entrepreneurs to develop on land near the newly established rail roads.

Reconstruction ended with the Compromise of 1877 which installed the Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in the White House and gave the Democrats control of all state governments in the South. Although the Democrat, Samuel J. Tilden had won the popular vote, he was short of votes in the electoral college, with the electoral votes of three states, Florida included, disputed. The disputed states gave their electoral votes to Hayes as part of this compromise, making Hayes president.

Immigration

[edit | edit source]Ironically, Florida encouraged immigration in order to fill jobs and boost the economy. The Bureau of Immigration was used to abolish immigration tax in order to expand immigration in Florida. Florida tried to encourage people of the same religion and ethnicity to reside in the same areas as each other because they thought it would be easier for people to live in an environment they were already confortable in. They also attempted to attract wealthy land owners to come to Florida and not go to other booming states such as California by advertising their freed slaves as cheap labor. One reason why people might have been less accepting is because Florida was already apart of the confederate states, which meant they were pro-slavery and still looked at black people as property. In many cases former slave owners believed that a new government might let them keep their slaves or at least pay them for what they considered lost property. These were key indicators of how racist the south really was. Also, there were already Seminoles residing in Florida, which was another reason why southerners were not as welcoming of new immigrants because they wanted to feel a sense of security. This made Florida a more segregated state by choosing to have the different ethnic groups separated.

Even though many people disagreed upon diversifying Florida at the time, it has helped shape America into what it is today. Florida housed a variety of ethnicities, who brought their own way of life to the United States. This newfound diversity was plenty for Floridians to handle at the time because of what they lost in the civil war (eg. land and slave labour) and because of the lack of compensation from the federal government.

Further Reading:

[edit | edit source]- Catton, Bruce. Civil War. England: MARINER Books, 2004,p. 15-16.

- Davis, William W., The Civil War and Reconstruction in Florida. New York: Columbia University, 1913.

- Johns, John, E. Florida during the Civil War. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1963.

- McDonough, James. War so Terrible. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987, p. 6-7.

- Murphree, R. Boyd, `Florida and the Civil War: a Short History`. Available at https://www.floridamemory.com/collections/civilwarguide/history.php Accessed 3 November 2015.

- Nulty, William H., Confederate Florida: the Road to Olustee. Tuscaloosca: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

- Richardson, Joe M., `The Freedmen’s Bureau and Negro Education in Florida`, The Journal of Negro Education 31 (1962), pp. 460-467

- Shofner, Jerell, H., `Negro Laborers and the Forest Industries in Reconstruction Florida`, Journal of Forest History 19 (1975), pp. 180-191

- Taylor, Robert. "Unforgotten Threat: Florida Seminoles in the Civil War." Vol. 69 (1991), p.302-303.

- Winsboro, Irvin. "Give Them Their Due: A Reassessment of African Americans and Union Military Service in Florida during the Civil War." Vol. 92(3) (2007), p. 332-333.

- Wynne, Lewis N., and Taylor, Robert. Florida in the Civil War. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

- French, Mary. Chronology and Documentary Handbook of the State of Florida, Oceana Publications Inc, 1973.