History of Alaska/Printable version

| This is the print version of History of Alaska You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/History_of_Alaska

Introduction

The name Alaska comes from the Aleut word "aláxsxaq" meaning “the mainland or where the action of the sea is directed”. Alaska, the largest state in terms of area in the United States, was admitted to the Union on January 3, 1959 as the 49th state. Alaska is located in the far northwestern corner of the North American continent by the Canadian Province of British Columbia and the Canadian territory of the Yukon. To the north of the state lay the Chukchi and Beaufort seas, and to the south and south-west lies the Pacific Ocean. The population of Alaska is currently about 710 231, most of which are clustered around the city of Anchorage, located in South Central.

Before America acquired Alaska in 1867, Russia maintained control of the land. This began in 1741 when, Russian explorer, Vitus Bering first sighted Alaska. After this initial discovery, Russians began to settle Kodiak Island in 1784. The settlers thrived on the plentiful fur acquired from animals such as otters and other Nordic animals. Other countries such as Britain and Spain tried to explore Alaska, but they failed due to the dominant presence of the Russians. In 1867, U.S secretary of state, William Henry Seward bought the territory of Alaska from the Russia for 7.2 million dollars, less than 2 cents an acre. The Russian decision to sell their former colony came as a result of Russia being in a financially troubled situation, as well as due to fears that they would lose the colony without compensation, especially to the British. In 1859, the Russians approached both Great Britain and the United States and offered to sell them the colony, however, the British didn’t express any interest in buying the colony. At this time the Americans did not express any interest either, as the risk of an American civil war was a more pressing concern. Thus it wasn’t until after the civil war that the United States re-approached the Russian Empire in hopes of purchasing the colony. Many Americans were cynical about this purchase and the transaction consequently came to be known as “Seward's Folly”.

For people who are interested in travelling to Alaska, the state prides itself on countless breathtaking views as well as a coastline longer than the cumulative coastline of the contiguous state. Additionally, the wildlife in the "Last Frontier" state is unlike any other part of the United States and there are many species indigenous to Alaska that are worth viewing first hand.

Beginning

[edit | edit source]Approximately 15 000 years ago, Indigenous peoples crossed the Bering land bridge into the western part of Alaska. In general, the Tinglit and Haida peoples occupied the southern part of Alaska, the Aleuts settled in the Western hemisphere, and the Inuit and Eskimo on the Arctic Ocean coast.

Over time, the rest of Alaska's vast landscape was consumed by other Indigenous people until the European invasion. Precolonial estimates place Alaska’s population at approximately 80,000. Russian explorers arrived in Alaska during the mid-18th century, colonizing and transforming the peninsula and its surrounding islands into a fur trade hub. In the early-mid 19th century, British and American settlers arrived to establish similar enterprises, competing with Russia over dominance of the land and sea. The triangular trade relationship formed by these three nations would dictate much of Alaska’s political and economic landscape until the territory was finally purchased by the United States in 1867.

Exploration & Political Developments

[edit | edit source]In 1741, the first Russian explorers arrived in Alaska on two ships, commanded by captains Vitus Bering and Aleksei Chirikov. Chirikov survived the voyage home but Berin died after being shipwrecked on an island that would later bear his name. They brought back with them high-quality sea otter pelts, and further expeditions across the Bering Sea were launched, beginning the age of Russian American colonization. However, Russia wasn’t the only country to shown an interest in Alaska. Within the final decade of the 18th century, British sailors had already extensively charted most of the region, and Spain had successfully explored the southeastern Alaskan waters. Even France had shown interest in Alaska with an expedition in 1786 to the southeast. It wasn’t until 1798 when America itself finally joined the others on the northern peninsula.

The political landscape of late 18th-century Alaska, leading up to 1867, could be described as a series of competing company and colonial interests amongst the nations who’d staked a claim in the territory. Chief among these was the Russian American Company, which held possession of the entire landmass and divided it into six parcels. In 1824, the Russian American Company signed a treaty with the United States that would allow for equal trading privileges between both nations for a period of 10 years. It also signed a similar treaty with England the following year. After the ten-year period expired Russia forbid the United States from pursuing business interests in the territory. The English, anticipating a similar exclusion, sought to hold a part of their territory through military force, but were forced back by Russia. They negotiated a second treaty which required them to pay 2000 otter skins annually until 1867. The Hudson Bay Company, along with and America's growing whaling industry, threatened Russian dominance over Alaska throughout the 1840s. However, the greatest blow to Russian America was dealt from outside the continent, as the Crimean War and Napoleon’s continental system had turned Russia’s sole maritime territory from a boon to a burden, and in 1863, the Russian America Company failed to renew its charter.

In light of these problems, Russia decided to sell its territory. In 1859, the Russians approached both England and the United States with offers to sell them the colony. England declined, but America, which had been expanding across the continent and had prosperous whaling industry, showed an interest in buying. In 1867, U.S secretary of state William Henry Seward bought the territory for 7.2 million dollars. This marked the official end of the Russian America experiment and the beginning of post-Russia Alaska. The acquisition of Alaska by the United States marked a detour in domestic policy: before its purchase, all territories inducted into the United States were expected to eventually join the Union. Alaska would be an exception, and would not officially join the United States for yet another century.

Becoming a State

[edit | edit source]After the Alaskan purchase, the territory was officially incorporated into the United States of America as the Department of Alaska. The Department of Alaska lasted from the territory’s incorporation in 1867 up until May 12, 1884, when it became the District of Alaska. During the department era, Alaska fell under the jurisdiction of the US army, the Department of the Treasury, and the Navy respectively. In 1884 the First Organic Act was passed which allowed the territory to become a judicial district, with judges, clerks, and other government positions being appointed by the Federal government. Alaska then became known as the District of Alaska up until 1912, where it was organized into a territory. The territory of Alaska was created on the 24th of August, 1912. By this time, the population had swelled considerably due to the many gold rushes which took place in the late 19th and early 20th century. Alaska officially became the 49th state of the United States on January 3, 1959. President Eisenhower signed a proclamation and Alaska became part of the union. It was not easy for it to become a state; residents had to convince Congress they were good citizens and were able to sustain the future of the state. Legislators were concerned that the population level was too low, the land was isolated and there was no economic potential. However, by the end of World War II, Alaska had gained recognition for the valuable wartime advantages it gave and the movement towards statehood officially began. Despite the legislators' concerns, they still took the chance regardless because of the massive amount of land it has and its advantages during the war.

Geography

[edit | edit source]Situated at the North West corner of the North American content, Alaska prides itself on its gorgeous landscape, peaceful environment and physical characteristics. The geography and weather of Alaska is such that overland travel was, and still is difficult. However, the development of aircraft allowed for an influx of settlers into the interior of the region, as well as rapid transportation of goods and peoples.

Aside from the Canadian territory to the east, the state is almost completely surrounded by water. The Arctic Ocean feeds the Beaufort Sea which encompasses the Northern Alaskan coast, while the Gulf of Alaska and Pacific Ocean covers the southern border. To the West, the Bering Strait and Chukchi Strait separate Alaska from the Asian content. About 30% of the state lies within the Arctic Circle.This explains why the northern part of Alaska is mostly filled with glaciers and icebergs, which contains the majority of the world's fresh water. However, global warming has increased seasonal temperatures causing glaciers and polar ice caps to melt, thus endangering many animals such as polar bears and sea otters.

In addition, Alaska is filled with a variety of landforms such as mountains, hills, and valleys. Many of the mountains have different altitudes ranging from 2000-20 000 feet. It also consists of many lakes and rivers all across. Moreover, It has a very rugged landscape and has thick regions of forest that consist of diverse wildlife. Additionally, there are many active volcanoes throughout Alaska.

The climate varies in Alaska across different regions. In the winter, it tends to snow quite a bit and there are many blizzards and snow storms. It is freezing cold and temperatures normally reach between minus 15 to minus 20. In the summer it rains a lot and thunderstorms are common. During this season, temperatures are relatively higher, usually around 10-15 degrees Celsius.

Alaska is the United States' link to the Arctic and allows the nation to be one of the eight nations globally that own land inside of the Arctic Circle, according the U.S. Geological Survey.6 Alaska is the gateway to the Arctic for the world's most powerful nation and therefore plays a huge role in climate change diplomacy. Many internal disputes between settler communities and Alaskan natives have arisen due to the importance to the regions climate.

Demographics

[edit | edit source]Due to its far north location as well as having an arctic climate, Alaska is one the most sparsely populated and least dense subnational territories in the world. Having a population just below three-quarters of a million people in 2016, Alaska would be the United States' 19th most populous city with an area the cumulative size of the twenty two smallest states. Being as sparse as Alaska leads to harder living conditions for the state's residents.

The Klondike gold rush at the end of the 19th century lead to thousands of men and women drifting and begin permanently residing in Alaska, mostly in Juneau, where gold had been discovered some two decades earlier. Population growth continued in Alaska for the next few decades and by 1940, there were nearly seventy-five thousand individuals living in the territory. Approximately forty-five percent, or thirty-four thousand, of the people living in Alaska in 1940 were Native peoples. However, by the early 21st century, Native peoples only made up fifteen percent of the nearly seven hundred thousand Alaskans.

Economy

[edit | edit source]

The economic history of Alaska is primarily rooted in natural and non-renewable resources. After William Seward initiated the purchase of Alaska in 1867, US settlers migrated to the new region to pursue the economic potential of the land's plentiful hunting and fishing.

Travel and Roadways

[edit | edit source]Alaska has a much less comprehensive road system than the forty-eight contiguous to the south. For example, the states capital, Juneau, is not accessible by road. Many cities have small airports to help shorten travel times over the large region as well as to make smaller cities more easily accessible. The difficulty to travel to many of the communities within the state leads Alaskans to have one of the highest costs of living in the developed world as companies charge high prices to reach the rural regions, especially in the western regions of the state.

Alaska is heavily dependent on tourism, and though it has seen some success in this industry in the past, the state will have to develop a more sustainable and internal economy in order to become more prosperous and rely on the federal government less. However, the lack of usable infrastructure, including roads and railways, as well as the harsh climate leads Alaska to being a seldom chosen vacation destination among not only American's but other nations as well.

In the 1990s Alaska faced great economic uncertainty due to a decrease in oil production as well as a decline in the production of many of the other non-renewable resources the state's economy had been based on for decades. This lead Alaska to rely more on tourism as well as federal government spending. With much of the economy based on non-renewable resources as well as being a point of low interest for travelers, means Alaska's old way of economic survival may not last much longer.

Already being the least urban of states, Alaska will continue to fall behind in many senses in the coming years unless a change comes about.

Animal Fur

[edit | edit source]Alaska has a diverse range of animals across its lands. International demand for fur from animals such as seals, sea otters, foxes and other mammals led to The Fur Trade becoming Alaska's primary export and source of income. The fur was used for coats, hats and other clothing.

Deforestation and Fishing

[edit | edit source]Likewise, deforestation and fishing provided huge income to Alaska. As national and international demand for lumber increased, many leaders turned their attention to Alaska because of the tremendous amount of forests. This resulted in a huge increase in local employment as Alaska created a huge labour force in logging and forestry to adhere to the international needs.

In addition, commercial fishing was very prevalent in Alaska because it is surrounded by large bodies of water. There are large fishing ports all around and this was an in-demand commodity at the time.

Mining

[edit | edit source]Alaska's economy, and subsequently their population, began to explode with the multiple discoveries of gold between 1880-1890. In 1880, the first deposit of gold was discovered by Richard T. Harris and Joseph Juneau near the modern-day capital of Juneau. While the Juneau mining community continued to grow, George W. Carmack discovered more gold in 1896 along an offshoot of the Klondike River. News of this discovery reached mainland America in 1897, and the gold rush began. Between 1890-1900 the population of Alaska doubled as thousands of families migrated north in pursuit of financial gain. By 1904, Alaska had the largest gold mine in the world. An estimation of about 100 000 migrated and over 1 million pounds of gold had been mined. A lot of people who travelled there chose to stay and settle, thus increasing the natural population.

The effects of the gold rush had a profound impact on Alaska's position within the American economy and subsequently American politics. With an influx of American people into a primarily native population, the question of Native-American citizenship arose. Although the rush had integrated Alaska into the US economy, it remained unclear if the number of American settlers was significant enough to grant the territory political significance.

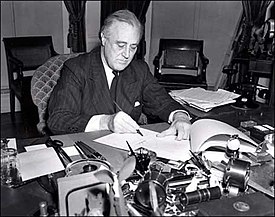

Fishing and mining remained the essential economic sources for Alaska's settlers until World War II. Brief Japanese occupation of the Aleutian Islands persuaded the Roosevelt administration to implement new infrastructure projects to strengthen the northern territory. These projects included communication initiatives, such as telephone lines and transportation infrastructure such as roads and airports. These projects established reliable access to oil and other natural resources to the American mainland.

Thousands of workers migrated to Alaska to take advantage of the numerous job opportunities these projects created. Of all the projects, The Alaska highway project (ALCAN) required the majority of involvement. The ALCAN was a proposed 1450 miles, connecting Alaska to mainland America through the Canadian territory.

The US government passed the 100-million-dollar project in February 1942. Following Canada's approval in March, General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr. was given the sole responsibility of executing the plan on May 1, 1942.

Of the thousands of the Army Corps of Engineers that were enlisted to construct the road, one third were African American. Initially, black troops were employed to service the white soldiers, since authority figures assumed the African Americans were incapable of functioning in the cold. However, due to a lack of labourers and a pressing schedule, black troops were assigned to traditional white tasks. In the end, the African American soldiers were critical in constructing the strategic milestone in only eight months and twelve days.

Oil

[edit | edit source]In addition, oil is a significant part of Alaska's economy. Economic interest in Alaska surged once again in 1968 upon the discovery of the largest oil field in North America, Prudhoe Bay. Upon discovery, this oil field was estimated to contain 40 billion barrels of oil trapped beneath the Arctic Ocean. In 1969, eight oil companies, including the discovering parties, Atlantic Richfield Company and Humble Oil proposed forging of a 900-million-dollar pipeline stretching 800 miles from Prudhoe Bay to the more accessible Valdez port.

This discovery brought forth long-standing complications regarding land ownership between the US government and the Native peoples.Before the pipeline could continue, the stakeholders had to establish clear ownership rights regarding land ownership and the distribution of resources of this land. The Nixon administration appeased this conflict by introducing the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971. This agreement permitted the exchange of 960 million acres of established Native land for 962 million dollars and 45 million acres in other parts of the state.

With the land dispute settled, construction on the Trans-Alaska pipeline began in 1974.

Being an oil rich state, Alaska relied on the expansion of pipelines to transport the oil from the north into the continental United States hundreds of miles south. This caused more disputes between Native Alaskans and brought up concerns for the regions environmental future. Oil transportation also created concerns for Alaska's other economic sectors that rely on the regions natural resources, specifically agriculture.

The discovery of oil had singlehandedly made Alaska one of the wealthiest states in America. Alaska sold its rights and made agreements with oil companies so they can create a pipeline and drill for oil. Alaska made billions of dollars from its oil reserves. This also helped stimulate the economy financially by increasing the amount of well-paying jobs in the oil sector. The price of oil dropped as a result. Many people, who were jobless and poor, were now acquiring jobs to help support their family and make a decent living.

Alaskan Permanent Fund

[edit | edit source]As the completion of the Trans-Alaskan pipeline neared, legislative leaders such as Hugh Malone and Governor Jay Hammon developed the idea of a permanent fund to extend the revenues from nonrenewable resources to future generations. This plan came to fruition in 1976, when Alaskans voted to amend their state constitution and place at least 25 percent of all mineral revenue into a fund for future generations.

With the completion of the Trans Alaskan pipeline in 1977, business in Alaska began to boom, and the political leaders discussed the optimal method to distribute the fund. In 1980, the Alaskan legislature established The Permanent Fund Dividends, making the nest egg more accessible Alaska's citizens. By 1982, eighty-six percent of state revenues came from the oil industry and by 1992 the fund was worth fifteen billion dollars. Details of this can be found here: Alaska Permanent Fund

World War I

[edit | edit source]The first World War drastically slowed down the economic expansion of Alaska, and brought an economic depression to the area, many individuals lost their jobs or were enlisted to fight overseas. Many of the male Alaskan residents left to fight in the war. Of those who returned to America, many were unlikely to return to Alaskan territory. Post-war, the prices for Alaska's two main exports, copper, and salmon, lost value dramatically. The decline in price for these two major exports had a major effect on the economy and Alaskan standard of living as a whole. The economic downturn leads the abrupt stop in the Alaskan Railroad, limiting migration from the US mainland to the north. This had major implications for Alaska's population. Post World War I marked an all-time low for Alaska’s economy.

World War II

[edit | edit source]Alaska, being extremely close to Russia and Japan, made for, arguably, the most important strategic position for the United States of America during both World War II and the Cold War. America, however, did not realize their advantage until General William Mitchell fought for air defence in Alaska and said, “He who holds Alaska holds the world” in Congress in 1935. Due to their forced realization and the General’s fight for a stronger defence, America built naval bases such as Dutch Harbour and Kodiak to protect their weak northwestern front.Planes leaving from these harbours could not travel far enough out west; thus, refuelling stops were built on the Aleutian Islands strategically to allow for further travel out west. The Lend-Lease Act passed in 1941, which allowed their then ally, Russia, to fly American planes through the Alaska-Siberia route to use the planes in the battle against the Germans on Russia’s western front.

The Lend-Lease Act proved successful, making up 12% of the Red Air Force and devastating Hitler’s troops, showing Alaska’s value as a strategic base during World War II. Not long after the bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941, the valuable Dutch Harbour was bombed by the Japanese in 1942. While ignored in history, the Japanese went as far as occupying the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska as part of their plan to expand in North America; though many historians will also argue that the occupation of the islands was merely a distraction for a more significant attack on Midway Island in the middle of the Pacific. This marked the first time that a foreign force has occupied American land since the war of 1812. Due to this occupation, 44 Americans were taken as prisoners by Japan, 17 of them dying. Given the occupation of the Aleutian Islands, it is arguable that the Alaskan people were reasonably suspicious of Japanese-Americans and the possibility of them betraying the country. Therefore, as was seen in the most of America, many Japanese-Americans were taken to internment camps from their homes in Alaska. This fear came along with the anxiety of a larger attack by the Japanese which led to food rationing and obligatory blackouts. In May 1943, American troops arrived to get rid of the Japanese occupation in the Aleutian Islands. Almost unbeknownst to history was the combat that took place on Alaskan soil.

The actual fighting during the battle of the Aleutian Islands lasted for nineteen days, and by the end of the occupation of Attu, only 29 Japanese prisoners remained of the initial 2600 that had fought against the Americans.As for the Island of Kiska, the other occupied island, before American troops could even arrive to push the Japanese out of the land, the Japanese had already evacuated. Thus, after making sure the island was secure, the only World War II battle ever fought on American soil officially ended two months after it began, in August 1943.

As a result of Alaska’s involvement in World War II, a supply route had to be built. The Alaska Highway, then called the Alcan Highway, was built by 11 000 troops in 1942 connecting Alaska to the rest of America through Canada. At this time, black soldiers were still deemed to be incapable of frontline duties; however, their work on the Alaska Highway greatly contributed to the historic integration of the army, which occurred in 1948. Due to the new connection and newfound jobs at the naval bases in Alaska, there was a population boom, and by just the end of the 1940s, the population had gone from 72 000 to almost 129 000. By the end of World War II, Alaska had gained recognition for the valuable wartime advantages it gave and the movement towards statehood officially began.

The Cold War

[edit | edit source]As the American people were just beginning to recover from World War II, the fear of a Soviet attack grew rapidly, and the Cold War began. Russia had built four-engine powered bombers which could reach Alaska on a one-way trip across the north pole. The American government believed that if Russia captured even one of Alaska’s islands, it could be used as a refueling point to extend Soviet bomber range, resulting in unimaginable harm to the American people. Thus, given Alaska’s proximity to Russia and the possible danger this presented, the state was thrust onto the frontline of the Cold War. Just as it had been during World War II, Alaska once again became an active air defense center.

During World War II, Alaska focused on fighting the Japanese coming from the south, not an enemy coming from the north. When the Cold War began, new bases needed to be built that could defend America from their northern foe. As a result, new Air Force bases were constructed strategically to combat their new enemy, Russia. In 1949, when the Soviet’s detonated their first atomic bomb, the American government panicked, and new technological advancements were funded to combat Soviet progress. From 1951 to 1958, Aircraft Control and Warning systems were constructed to detect Soviet bombers and stop them in their path, 18 of these systems were placed in Alaska.

However, the system proved unsuccessful in giving an early warning. Thus, the Distant Early Warning Line was constructed, twenty-four of them stationed in Alaska. The “Mile 26” base, renamed Eielson AFB in 1948, was modified to accommodate the planned deployment of Strategic Air Command intercontinental bombers. The massive Convair B-36 "Peacekeeper" bomber was the largest bomber in the US Air Force’s inventory, and the largest hangar on Eielson today was originally built to house two B-36 bombers. The existing west runway was expanded in 1946 to a length of 14,500 feet, making Eielson the Air Force base with the longest runway in North America, and consequently the most well known base in Alaska at the time. Strategically, by using polar routes, Eielson's location allows units based here to respond to hot spots in Europe faster than units at bases on the East Coast. The same is true for Korea and the Far East, where Eielson based units can respond quicker than many units based in California.

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched its first intercontinental ballistic missile (ICMB), followed by the world’s first satellite, Sputnik. This change in strategies by the Russians decreased the use of bombers. Thus there was less of a need for Alaska’s military bases. As ICMBs became a more imminent threat, warning radar bases providing incoming missile warnings became Alaska’s primary job throughout the rest of the Cold War.

Aboriginal Alaxsxaq (to 1800)

Indigenous Origin Theories

[edit | edit source]The Bering Land Bridge Theory

[edit | edit source]

The Bering Land Bridge Theory is one of the most widely supported theories explaining how Paleoindians came to inhabit North America. The theory hypothesizes that when glaciers blocking the Bering Strait began to melt approximately 12,000 years ago, they broke into sheets that carved out a path of land approximately 1,000 kilometres long. This temporary path could have been crossed by Paleoindians from Siberia into Alaska, explaining how North America became inhabited by humans as well as many species of plants and animals. Recent grass and sage fossils found in eastern Beringia suggest that the area was a part of the mammoth steppe, a system of dry grassland climate stretched from Europe, through Eurasia and eastwards onto Canada and played the role of a ‘safe haven’ for many species escaping the ice age.

Most historians and other scholars believe that people from Asia were able to cross the Beringia during the Ice Age, specifically the Pleistocene epoch, between 12,000 and 60,000 years ago. These people became the first natives of Alaska, most likely belonging to either the Nenana or Denali complexes that eventually settled in central Alaska. It is believed that all of the natives in Alaska descended from these original groups as they share many similar characteristics. Their physical similarities, for example, dark hair, and eyes, set them apart from the European settlers. Over time, the hunter-gatherer communities continued to migrate from Asia to North America in search of fertile land. It was only until after the glaciers south of the mammoth steppe begin to melt did the Paleo-Indians continue their migration southward, making way for the possibility of the Denali and Nenana people are the first ancestors of all human life in the western world. However, scientists and historians continue to dispute on the timeline, as well as whether or not the materials excavated in the south match the original tools from the Alaskan complexes.

In the mid-1700’s when the Russians first made contact with the people spread out across North America and particularly Alaska, it was theorized that these people had originally came from northeast Asia across the Bering land bridge. Vitus Bering, a Danish explorer in the service of Russia found this strait during his voyages in the years of 1728, and 1733-1741. Bering’s discovery of this strait was Russia’s “formal claim to what is now Alaska,” according to Karam. As the Russians had claimed this first, they saw it as theirs instead of being part of early America. For over a century Russians dominated and controlled Alaska and the natives that were living there. The Bering land bridge made travel easier between Asia and North America. It was also seen as an advantageous area for military attacks and trading ports.

Controversy

[edit | edit source]Although the Bering land bridge theory is widely supported in the scientific community it is also frequently critiqued, especially among First Nations, for its use in discrediting Aboriginal claims to land and justifying their physical and cultural displacement by European powers. Some historians argue that there is no evidence to support the theory that people could have survived the trek to Alaska through such a harsh environment. Many would have died from diseases, famine, and cold climate conditions. There is minimal archaeological evidence from this time to support this theory. Although there were Indigenous populations there when the Russians arrived, there was no telling of how exactly they got there. Later Europeans dubbed them “Indians” who had settled in North and South America. The Bering Land Bridge Theory is also criticized for its lack of evidence in the oral histories of Indigenous people.

The time frame in which the Bering Strait would have been accessible to humans has also been disputed. Tools manufactured by humans discovered at an excavation in Clovis, New Mexico has been dated back to 11,000 years ago, supporting the theory. In 1978, however, an archaeological expedition in Monte Verde led to the discovery of relics including the remains of hunted animals and spearheads dating 13,000 years ago, putting the Bering Land Bridge Theory in contention.

Other Theories

[edit | edit source]Some theories propose that two migrations across the Bering Land Bridge occurred throughout history. This theory supports the original Bering Land Bridge Theory but adds that the second migration of people occurred approximately 5000 years ago, populating Alaska. This theory is supported by similarities in skull measurements collected from human remains. The same criticism that surrounds the Bering Land Bridge Theory also applies to this theory, but it is also disputed by researchers who deny that there is any link between the size of a skull and genetic history.

Another theory suggests that a group of people sailed along the Bering Strait to reach North America. The Bering Land Bridge Theory, which suggests that a group of people walked across the Bering Strait during a specific period of time when the glaciers were melting, is constrained by the specific circumstances that it suggests. If a group of people instead sailed along the Bering Strait, it would leave the period of human migration open to a much larger period of time and explain any artifacts that predate the Bering Land Bridge Theory.

Other theories contend that the Indigenous people of North America are descended from a different species of human distinct from those who populate Europe. This theory potentially has some overlap with the Bering Land Bridge theory, suggesting that some First Nations, including many residing in Alaska, are descended from people who migrated across the Bering Strait, while others are descended from a distinct species of human.

Native Ethnology

[edit | edit source]Although the terms 'Eskimo' or 'Esquimaux' have been used to refer to the inhabitants of Alaska, they are broad terms applied by Europeans to the numerous and culturally distinct tribes of Indigenous people that live in Alaska. These terms generally refer to the Inupiat and Yup’ik peoples of Alaska collectively. Upon the discovery of Alaska by Russian explorers in 1741, the land was made up of several distinct cultures, including the Inuit, Athabascan, Aleut, Inupiat, Yup’ik, and several other southern coastal nations.

Inuit

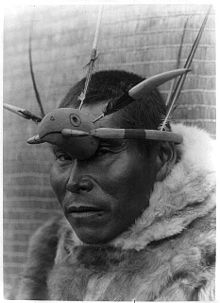

[edit | edit source]

The Inuit were located along the coast of Alaska, from the Alaskan Peninsula to the Arctic region. Many of cultures that made up the population originated from the Inuit, such as the Inupiat. They were known for their peaceful nature and for their poetry and music. They were primarily meat eaters since they hunted caribou in the summer months and lived off of salmon and other sea mammals in the winter. In the summer, they built tents from the skins and furs of animals they hunted, whereas, in the winter, they constructed snow houses for residence.

Athabascan

[edit | edit source]The Athabascans were located in the interior of Alaska. Eleven different languages were spoken throughout Athabascan society, with dialects dividing each family of languages even further. The Athabascans took residence over a large area of land, migrating to different parts of the region depending on the season. They were also known as hunters and trappers.

Aleut

[edit | edit source]

The Aleuts were located on the Aleutian Islands. Their culture was unique from other Alaskan cultures due to the isolated nature of their islands. They were named Aleuts by Russian explorers but traditionally referred to themselves as Unangax or Unangan. Following the Russian discovery of Alaska in 1741, Russian explorers and hunters heavily depended on the Aleuts, who were adept hunters. Russian fur hunters known as the promyshlenniki forced the Aleuts to hunt pelts for them since they themselves were unfamiliar with hunting sea mammals in this territory.

Inupiat

[edit | edit source]The Inupiat were located within the northern region. They are divided into groups, each being unique by dialect and environmental differences. The Bering Straits, North Alaska Coast, and Interior North Alaska Coast Inupiat make up three distinct groups separated by geographical location. The Kotzebue-sound and Norton-sound Inupiat have been grouped by dialect.

Yup’ik

[edit | edit source]

Having been isolated by mountain ranges and distances from other Indigenous peoples, the migrants from Asia created a culture and language to define them. As Alaskan natives, they formed many different groups fanning out across the expanse, with continued differences including language or dialect. Some peoples focused on the sea as a source of food while others pursued the caribou. The Yup’ik was one distinct group that settled in the western part of Alaska. Yup’ik natives were called Eskimo-Yup’ik to distinguish them from other Eskimo communities.

The Yup’ik community was located in southwestern Alaska near the shores of what we now call Koyuk, closest to Asia and Russia. Their territory did not expand too far inland. They were individual tribes that all made up one location, however, the boundaries were unclear. They mostly lived in coastal areas and traded with inland villages as they had access to trade routes and the sea. The Yup'ik have historically been separated into two divisions of distinct culture: the Siberian Yup’ik and the Central Yup’ik. The Siberian Yup’ik resided on St. Lawrence Island, whereas the Central Yup’ik were located in the southwestern area of mainland Alaska. Each division of the Yup’ik held their own individual social and cultural practices. There were many tribal wars between the Yup’ik and the Athabascan over territorial disputes. The Yup’ik were settling along the lower regions of the Yukon River once they came to Alaska.

The Yup’ik were an Indigenous tribe that was known for their fishing and hunting skills. As they were a very mobile group, the clothes that they wore reflected their lifestyle of being outdoors. They would wear animal furs that were waterproof and warm to protect themselves during the cold winters. They would travel often in search of food and would follow whatever big game was in the area. They heavily depended on migratory salmon and hunting sea animals along the Bering Sea coast. They traded fur and pelts with the Europeans for other food sources and materials. In 1799 the Russians formed an agreement with the Americans to have an outpost in this area and took over the fur trade and exploited the Yup’ik in order to gain control of the valuable resources of Alaska.

A ‘qasgiq’ was known as a community center where members of the tribe would gather for social interactions. Often at these meetings, there would be eating, dancing and singing, and celebrations taking place. It would be considered the equivalent of a church. It was highly respected and was a place where religious festivities took place. There are certain types of music that were played in order to represent where the tribe came from and how the natives used what they had to make sounds. The drum is the center of music while dancing was happening. The drum represents new life returning after death, a renewal of sorts that allows the Yup’ik to survive.

The Yup’ik had certain religious beliefs including believing in good and evil shamans. The good shamans performed magical acts and would help people, whereas the evil shamans would cast spells and create bad omens. They were a very superstitious group who believed in a balanced life. ‘Ellam Yua’ is the belief that every living thing is tied to a spirit. The Yup’ik believed strongly in this idea. This meant that they had to treat living things with respect even though they had to kill animals for food. Something that is still practiced in the Yup’ik society today are the rules for how each animal is killed, there are different instructions to follow so that the order of life remains intact. There are connections between the human and animal world. The Yup’ik live in peace with the animals on their land and always give back to the earth in some way to repay it for everything it has given them.

The 20th century brought change to the land distributions for the Yup’ik as they started expanding and moving into the Arctic Wrangell Island and the shores of the Gulf of Anadyr, up to the mouth of the Anadyr River. This tribe still continues its traditions today as part of the history of the people who migrated to Alaska.

Southern Coastal Nations

[edit | edit source]

The Haida, Tsimshian, and Tlingit cultures resided on the southeastern coast of Alaska. The Tlingit were well-known fishers, carvers, which included the making of canoes, and weavers. They were notably aggressive towards Russian settlers, instigating a war against those who encroached upon their land. The Kaigani, a subgroup of the Haida, drove the Tlingit out of Prince Wales Island and settled there. They were known for their carvings and paintings. The Tsimshian were located on Anette Island, although they were a very small nation.

Russian Alaska (1780-1867)

Introduction

[edit | edit source]Russian Alaska was the name given to Russian owned lands in North America during the years 1780-1867. Debates over who first discovered the land have been integral to the politics of Russian Alaska since its settlement. The first Russian settlements are most often dated to the seventeenth century. After the discovery of Alaska, news returned to Russia of resources available in America. A sort of “fur fever” began and a stream of Russian fur traders and Siberian merchants traveled to Russian America to take part. Fur trade companies quickly followed, supported by the Russian government. The companies sought to turn Russian Alaska into a commercialized and useful territory for the empire. Russian Alaska, in this period, was marked by instability and uncertainty regarding control of the territorial claims in America. Russia struggled to rule the far reaches of their empire and took a variety of actions to attempt to strengthen their authority in Alaska. The Russian-American Company was created to control Alaska while the Russian Orthodox Church was sent to civilize the Indigenous Alaskans. Both powers had distinct and lasting impacts on the native populations in Alaska.

Russian Exploration in Alaska

[edit | edit source]

Early Russian exploration into Alaska began in 1725 with the Kamchatka Expedition. This exploration mission was led by Vitus Bering, who originally left from St. Petersburg. He traveled North through Siberia and the Sea of Okhotsk to determine if there was a separation between Asia and America.

Bering was largely unsuccessful until 1741 when he eventually landed in Alaska. This would establish an early Russian claim to Alaskan lands. Unlike the British, the Russians were primarily concerned with the increasing capabilities of European empires, and were intent on modernizing and expanding their lagging empire. Subsequently, this was also the focus of the Spanish during the late eighteenth century, which increased tensions surrounding territorial claims and sovereignty.

Not only did the Russians attempt to disrupt Spanish territorial claims, the Russians would also bury and destroy possession plaques and royal crests that were involved in ritualistic British territorial claims to the land. Furthermore, British Captain, James Cook’s extended presence in Alaska prompted Catherine II to declare the Alaskan territory the possession of the Russian crown in 1786. The Russians eventually established a strong post at Nootka Sound, thus contributing to the Nootka Crisis of 1789.

Spanish Claims in the Pacific Northwest

[edit | edit source]

Spanish involvement in Alaskan territory developed shortly after Columbus’ initial journey in 1492. The discovery of new lands to the west of Europe and Africa meant that existing international agreements did not account for a large area of the world’s undeveloped land. This created conflict between Spain and Portugal, two countries with established imperial ambition in the fifteenth century. In the twenty years following Columbus’ initial voyage, Spain issued a series of claims to territory in North and South America, including present day Alaska.

The Inter Caetera, Treaty of Tordesillas, and Vasco Nunez de Balboa’s act of sovereignty were the three most notable Spanish claims during the early era of exploration. The Inter Caetera, a papal bull passed in 1493 by Pope Alexander VI, gave Spain sovereignty over any territory west and south of a meridian line approximately 550 km west of the Azores and Canary Islands. There are many interpretations of the bull, but the Spanish interpreted it as full sovereignty of all lands in the new world. In 1494, both the Spanish and Portuguese signed the Treaty of Tordesillas which created a new meridian line approximately 2000 km west of the Cape Verde Islands. This new meridian line granted Portugal all lands to the east and Spain all lands to the west of the line. Consequently, in 1513 Vasco Nunez de Balboa became the first European to reach the Pacific coast of the new world, and proclaimed all coastal lands in the name of Spain in a ceremonial act of sovereignty. Thus, from the early days of western exploration Spain had already established a claim to the entire Pacific coast of North and South America, including the land of present day Alaska.

Spanish Expeditions and Enforcement in the Pacific North-West

[edit | edit source]Spain never settled any effective colony north of Mexico by the middle of the seventeenth century. However, knowledge of Russian and British exploration in the north-west Pacific prompted Spain to build a naval base in San Blas, Mexico in the eighteenth century. This Naval base was mainly utilized for north-west exploration into Canada and Alaska. Russian fur trappers and hunters had established permanent settlement in Alaska, James Cook had made claims of British sovereignty, and Spain’s claims of ownership were fragile considering she did not have a single settlement north of California. Therefore, the Spanish Crown funded several journeys in the years between 1774 – 1794 to try to enforce Spanish control over the Pacific Northwest.

In 1774 and 1779, Bodega Y Quadra led the first two successful Spanish expeditions to Alaskan territory. These journeys marked the first time Spanish ships had sailed north of the Columbia River, eventually reaching latitude 60º North. Bodega Y Quadra and company explored many notable Alaskan landmarks (Puerto de Santa Cruz) and named many in the name of the Spanish Crown (although all names have been anglicized since). The Spaniards did not encounter any Russian or British inhabitants on these two early voyages, but they did perform symbolic “acts of sovereignty” that declared Spain’s ownership of the land. In the end, these two voyages were little more than a quick visit to the area.

In 1789, another Spanish expedition sailed to the Pacific Northwest to investigate Russian activity in the region. Esteban José Martinez and Gonzalo Lopez de Haro led the voyage and reached Alaskan waters in May. On June 30th the Spanish arrived at Three Saints Bay, where they encountered a Russian post commanded by Evstrat Declarov. Haro and Declarov exchanged goods and information, most notably Declarov informed Haro of the other Russian settlements in the area. With this information Haro and Martinez sailed to Unalaska where they received news that the Russians were preparing to occupy Nootka Sound, which was located off the west coast of Vancouver Island. The events of Haro and Martinez’s expedition led to an international crisis between Britain and Spain, deemed the Nootka Crisis. This voyage was the first meeting between Russian settlers and Spanish sailors. This signified Russia’s expansionist attitude, specifically, it showed that Russia was planning on colonizing southern territory and Spain would have to compete with other imperial powers to enforce their claim.

British Presence in Alaskan Territory

[edit | edit source]

In 1778 James Cook became the first British explorer to reach modern-day Alaska; his voyage signified Britain’s interest in the Pacific Northwest. Cook traveled to the Alaskan frontier in search of the Northwest Passage, sailing up the western coast of North America from California to the Bering Strait. Cook mapped a large portion of Alaska, including areas of the Bering Strait which had not previously been charted by Europeans. Cook also laid claims to the Pacific Northwest for Great Britain, an act that challenged Spain and introduced the west coast as a possible outlet for the British fur trade. The British believed they were entitled to the land following the Treaty of Paris signed in 1763, which settled land disputes between the United States and British North America. This treaty granted most of the land in Upper Canada to the British Crown.

Cook’s voyage spurred British development in the Pacific Northwest. This was an act that discredited Spanish claims and led to an increased British influence in Alaska. Moreover, James Cook led an expedition to Nootka Sound in 1786 where he executed early British territorial claims to the land. The British were primarily interested in these lands for their lucrative advantages to the fur trade. The Spanish Empire was forced to establish sovereignty over the lands not only due to British interest, but also because of growing concern for the Russians. British merchants began challenging Spain’s sovereign claims by engaging in commercial activity in the region. Subsequently, an expedition three years later led by James Colnett of the British Royal Navy discovered a Spanish garrison claiming sovereignty of the lands in Nootka. Colnett was apprehended promptly and had his ship seized, which led to the Nootka crisis of 1789 that brought Spain and England to the brink of war.

Tensions at Nootka Sound

[edit | edit source]Disputing Claims: Spain, Russia, and Great Britain

[edit | edit source]Spain believed they had territorial claims to the Pacific North-West through the Treaty of Tordesillas signed in 1494. Their naval base was mainly utilized for north-west exploration into Canada and Alaska. Juan Francisco de la Bodega commanded the Sonora and led an expedition to Alaska in 1775 to establish Spanish claims in Nootka Sound. After encountering Russian activity around the Pacific north-west and British utilizing the land for the fur trade, Spanish sovereignty on the Pacific coast had been compromised. By 1788, tensions escalated at Nootka, as the Spanish were not only concerned with British fur traders and increasing Russian activity, but also with the Indigenous peoples of Nootka. One of the Captain’s, Martinez, shot a Chief named Callicum who was well-respected among local settlers, the Indigenous of Nootka, and an advocate of English trade in the colony.

In addition to the dispute of claims by the Spanish, the British also believed they were entitled to the land at Nootka Sound because of a treaty of their own; the Treaty of Paris. The treaty was signed in 1763 and intended to bring an end to the Seven Years War. In addition to ending the war, the treaty also settled land disputes. The treaty “drew the line” between Canada and the United States and granted the British lands in Upper and Lower Canada. Thus, both nations believed they were entitled to the territory of Nootka Sound.

Unlike the British, the Russians were primarily concerned with the increasing capabilities of European empires, and were intent on modernizing and expanding their lagging empire. Subsequently, this was also the focus of the Spanish during the late 18th Century, which increased tensions surrounding territorial claims and sovereignty. Not only did the Russians attempt to disrupt Spanish territorial claims, the Russians would also bury and destroy possession plaques and royal crests that were involved in ritualistic British territorial claims to the land in Alaska. Furthermore, British Captain, James Cook’s extended presence in Alaska prompted Catherine II to declare the Alaskan territory to belong to the Russian crown in 1786. The Russians eventually established a strong post at Nootka Sound, thus contributing to the Nootka Crisis of 1789.

"Crisis of 1789"

[edit | edit source]

Nootka Sound is a network of islands off the coast of Vancouver Island. The Nootka Crisis of 1789 is important when considering the struggle for settlement and territorial claims in Alaska. The Nootka Crisis of 1789 emerged as a power struggle among three great powers: Russia, Spain, and Great Britain. The crisis became a political dispute among these powers, and almost began a war between Spain and Great Britain.

Due to the Treaty of Tordisilla and the Treaty of Paris both the Spanish and the British believed that they had rightful sovereignty over Nootka Sound. In addition to the territorial claims of Spain and Britain, Russian involvement in Alaska led to disputes about their right to the land as well. An exploration mission was led by Vitus Bering in 1741, and provided evidence for later territorial claims by the Russians. The Russians managed to set up a fairly successful post at Nootka Sound by the late 18th century. However, the explorations of James Cook led to a need for diplomatic intervention to solve the territorial dispute. Catherine II declared that all land north of Bering’s discovery was to be subject to the Russian crown. However, Britain's increased presence eventually suppressed Russian establishments in the Pacific north-west.

Although territorial claims were the contributing factor to the development of the crisis at Nootka Sound, it was the seizure of British fur trader ships that ignited the conflict. James Colnett of the British Royal Navy led an expedition to Nootka Sound in the spring of 1789, and upon arrival was arrested by a Spanish garrison who had claimed the territory of Alaska for Spain. This act prompted serious protest and backlash from the British and nearly pushed the two great powers to the brink of war. Along With the fear of British involvement at Nootka the tensions grew higher when a Spanish Captain, Martinez, shot and killed an Indigenous Chief named Callicum. It is well understood that the Chief was an advocate for the British fur trade although it is generally unclear why the Captain killed the Chief.

Demise of Spanish Involvement in the Pacific North-West

[edit | edit source]The Crisis ended with an agreement allowing Britain to settle in lands historically claimed by Spain, and led to widespread British settlement in present day British Columbia, Washington state, and Oregon. By the early 19th century the Hudson’s Bay Company opened a trading post on Vancouver Island. British settlement in the Pacific Northwest quickly expanded to consist of a vast network of trade between British merchants and their Russian (and increasingly American) neighbors to the North. By the mid-19th century the British population had grown substantially in the area. Diplomatic activity had reduced Spanish claims of sovereignty in Alaskan territory and commercial enterprises strongly linked Alaska and its neighbors.

Many other Spanish exploratory voyages occurred in the following decade, but none had much significance outside of ceremonial acts of sovereignty. The Malaspina voyage of 1789 led by Alejandro Malaspina and José de Bustamante y Guerra is perhaps the only exception as its purpose was largely scientific. Malaspina and crew searched for mineral deposits of gold and silver in Alaska, likely a prerequisite for Spanish colonization. However, the expedition also collected information on the Indigenous Tlingit community as well as glacial measurements. Spanish expeditions ended in 1794 and by 1819 Spain ceded their claims to Alaskan territory when they signed the Adams-Onis Treaty with the United States. Little Spanish influence remains in Alaska today, largely due to a lack of attempts at permanent settlement.

Early Russian Settlement and The Russian Fur Trade

[edit | edit source]There is some evidence that Russian settlements appeared in Alaska in the fifteenth century during the rule of Ivan the Terrible. However, most sources date the discovery of Russian America to the middle of the seventeenth century by Captain Vitus Bering, who led a government-sponsored expedition that visited the shores of the Gulf of Alaska. This expedition returned laden with sea otter pelts in 1741, which struck a pattern of sailors traveling to Alaska in small merchant vessels to hunt furs. This lead to the opening of the Aleutian Islands and mainland Alaska. It was not until forty years later that permanent settlements would come to Alaska.

Illiuliuk and Eguchshak were the earliest Russian settlements established on Unalaska Island in 1722-1775. However, the first permanent Russian settlements in Alaska were settled between 1784 and 1786 by the well-known merchant G.I. Shelikhov on Kodiak Island, located near the south coast of Alaska. In 1781 Shelikhov had petitioned the government to gain permission to establish a permanent colony in Alaska, he believed that a permanent settlement would serve to uphold Russian territorial claims and generate large fur revenues. In early August 1784, two vessels under the command of Shelikhov arrived on the coast of Kodiak Island. Here Shelikhov founded Three Saints Harbour, these settlements would serve as bases on the Pacific Islands and the Alaskan coastline for harvesting fur pelts. Three Saints Harbour became the first founding settlement of Russia’s colonial enterprise. Structures and facilities at Three Saints harbour included wooden buildings used as residences and company offices, earthen-walled workers’ barracks, a school, a cemetery, storehouse, gardens, and animal pens.

Three years after Shelikhov settled Three Saints Harbour, Pavel Lebedev-Lastochkin’s company was the first to settle the shores of Kenai Bay and then Chugach Sound in 1793, today's Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound respectively. Lebedev-Lastochkins men picked the mouth of the Katnu (Kenai) river for the establishment of their first settlement, named Pavlovskia, this settlement came to be the base for the Kenai Bay hunters throughout the years of Russian presence in Alaska. During the period from 1787-1798 Lebedev-Lastochkin’s employees explored new lands, built several settlements and small fur trading posts. The Lebedev-Lastochkin’s Company employees were the first to establish permanent contacts with the Tanaina Indigenous peoples which they referred to as Kenaitzy. Lebedev’s employees explored the shores of Kenai Bay and took hostages from the neighbouring Kenaitzy in order to secure their safety and barter for furs. The settlement of Pavlovskaia was not located far from the Indigenous village called Skittok, because of this many Natives lived alongside Lebedev’s employees in the twenty-three structures located in the fort. Some buildings in the fort were also used as facilities for teaching the indigenous children the Russian language. The settlement at Pavlovskaia faced some struggle in the late 1780s and early 1790s. July 1789, Stephen Ziakov the commander of the St. Paul, one of Lebedev’s ships and some other crewmen set sail for Okhotsk leaving thirty-eight Russians behind at Pavlovskaia. Over the next two years seven people died, supplies ran out, and everyone in the settlement developed low-spirits waiting for aid form Okhotsk. Although during those two years the settlement was able to gain 250 sea otter pelts, 500 arctic fox pelts, and 350 beaver and river otter pelts. The settlers bartered for these pelts with the Indigenous groups which had depleted the settlements exchange goods.

Lebedev’s company was the first to secure a position in Chugach Sound, and in 1793 his employees started building a fortified settlement in the southwestern part of modern Constantine harbour on Hinchinbrook Island. This settlement came to be known as Fort Konstantinouskaia. Just as they had done in Kenai Bay, Russians in Chugach Sound settled near Indigenous villages in order to establish a profitable barter. The most important goal of Lebedev’s company was to find profitable hunting grounds and to use the labour of skilled Indigenous fur and food hunters to their own benefit.

Originally, Russians and Siberians had engaged in agreement pertaining to the fur trade. However, as the fur trade continued, different companies emerged to deal with the increased pelt demand. Lebedev-Lastochkin’s company and Georgii Shelikhov's companies are two influential fur trading enterprises that emerged in this era. By the end of the 18th century, Shelikhov and Golikov’s company was a part of the main settlement on the Kodiak Islands. These companies eventually led to the creation of the Russian-American Company that became the ultimate representative of the crown in Russian America.

Russian settlers did not live without their share of troubles. Harsh conditions made life difficult for young fur traders, and a lack of young Russian women made companionship non-existent. It was difficult for settlers to become accustomed to the difference in climate, food, and the heavy workload. The difficult circumstances caused much discontent among the Settlers. In early years of Russian Settlement, there were many uprisings by Russian settlers protesting against the living conditions. Shelikhov used many tactics to try to keep his workers content but eventually resorted to trapping workers into financial contracts. As a result, workers became indebted to company owners for the duration of their work in Russian Alaska.

Russian Relations with the Indigenous Peoples of Alaska

[edit | edit source]The first contact between Russians and the Aleutian people likely occurred during the Bering Expeditions. Bering encountered the Aleutian peoples, or Aleuts as referred to by missionaries. Other Indigenous peoples encountered by the Russians were the Inuit, Athapascan, and Tlingit, among other existing tribes in the area. However, in studying Russian influence on these populations, the most notable is the influence upon the Aleutian peoples.

Relations between Aleutian peoples and Russian workers in Alaska included marriages between Russian men and Indigenous women. Aleutian hunters helped the fur trade, as their knowledge of the land and hunting skills were highly valuable to Russians. Bartering between Russians and Aleutians also took place. However, the Russians often exploited the Indigenous People of Alaska. The explicit commercial agenda of Russian colonization established the policies and practices of its colonists and structured their encounters with local populations. The primary interest in local Indigenous people was for exploitation as cheap labour by the fur trade companies. The Russians brought a practice of controlling the Indigenous people of Alaska, forcing them to pay a tax or a tribute in furs. Early exploitation of sea otters on the Aleutian Islands and Kodiak Island involved using military force against Indigenous communities, which included taking women and children as hostages to ensure that local Indigenous people paid their fur taxes. Catherine II banned this form of tribute in 1788, and replaced it with a mandatory conscription of Indigenous people to hunt for Russian companies. The Russian-American Company had difficulties recruiting Russian people to populate its colonies, and therefore heavily relied on the Indigenous population of Alaska for the economic continuation of their colonies. Due to this lack of Russians, the colonies supported few Europeans, but supported many Indigenous workers.

Russian immigrants had a major influence on the Native peoples and the cultural landscape of Alaska, that left lasting effects on the population today. Diseases brought over by the Russians, as well as early massacres, caused serious declines in the Indigenous population in Alaska. The effects of the Russian language on Native groups can also be seen through the use of "loan words". Similarly, The Russian Orthodox Church had a huge and lasting impact on the Indigenous Peoples of Alaska, and Orthodox Christianity remains the predominant religion within the native peoples of Alaska.

The Russian Orthodox Church

[edit | edit source]

The Russian Government employed many methods to strengthen their somewhat tenuous hold on Alaska during their control over the territory. One such way was through the Russian Orthodox Church. The missionaries, who followed the fur trade to Alaska, were directly connected to Russia’s plan for assimilation. Russian officials were aware of the controlling power of religion, and used it to their full advantage. The Orthodox Church made no attempts to disguise their motives and publicized their goal of “creating a preference for settled life and labor among the newly-baptized.” Religious conversion was viewed as a symbolic pledge of allegiance to the Russian Empire, and an important first step of assimilation into Russian culture. Assimilation remained a major goal in companies such as the Russian-American Company, throughout their existence.

The first group of Russian Orthodox Clergy arrived on Kodiak Island in Alaska in September of 1794 on orders from Catherine the Great. However, this was not Indigenous Alaskans first encounter with Russians or Orthodox Christianity. Russians who had first explored Alaska, or had come later for the fur trade, had converted some Indigenous Alaskans to Christianity as early as 1747. There were some instances of baptism of Indigenous people well before the arrival of the Orthodox Priests. The clergy was sent by request of Russian Fur Trade Companies who saw the opportunity to strengthen their control over, and commercialize, Alaska through the Orthodox Church. However, the relationship between the clergy and the Russians people living in Alaska was not as smooth as expected. Many Russians had taken informal Indigenous wives, and had stopped following the rules of the Orthodox Church. The new arrivals forced the Alaskan Russians to practice a religion they had grown unaccustomed to, which led to a great deal of resentment between the clergy and Russian Alaskans. The priests also disliked the Fur Trade Companies which had sought to use the clergy for their own gain. All churches, schools, pay, and living quarters of the clergy were funded by the Russian-American Company. As a result, the company had a great deal of control over the clergy and the mission could not function without the support and cooperation of the company.

After the abolition of the Patriarchate under Peter the Great in 1700, the Orthodox Church and the Russian state became more closely intertwined. In theory, The Tsar was the head of both Church and State, and had the opportunities to use the church to further his political agenda and gain control over the empire. During the reign of Nicolas I (1825-1855) the Russian Orthodox Priests were encouraged to adopt a more Protestant version of missional Christianity. The Priests were asked to add a component of political propaganda to their sermons, and serve as government officials in the new world. They were required to create reports, compile statistics, and deliver the news of new laws to the Indigenous population. Despite the actions taken by Russian officials to bolster missional Christianity in Russian America, Orthodox Christianity was met with mixed results until smallpox epidemics in 1835 and 1837 failed to be stopped by the local shamans. The priests were equipped with the smallpox vaccine, which assisted in the turning of Indigenous favours to Russian Orthodoxy. Policies implemented in the 1840s and 1850s also saw Indigenous Alaskans taking a larger role in the Orthodox Church. The native Alaskans filled the seminaries, and began to preach and proselytize to those not yet reached by the Russian Orthodox Priests. Relations between the priests and the Russian-American Company were better during this time and Russian Orthodox Christianity began to flourish.

The Russian Orthodox Mission to Alaska was limited by the small Russian population in Alaska. As a result, the mission was unable to reach vast areas of Alaska, and left groups of Indigenous Alaskans untouched by Christianity. To combat this issue, the Orthodox Church focused heavily on developing an Indigenous Alaskan clergy. A school had been established on Kodiak Island since the first arrival of missionaries in 1774, but had struggled due to the language barrier between Natives and Russians. As the language skills of the missionaries improved, more schools were built. A school was built in the Aleutians in 1825, and five more were established throughout Alaska by 1829. A theological school was also opened in Novo-Arkhangel’sk in 1841 which, when merged with the Kamchatka theological school in 1844, became a seminary able to educate Indigenous priests and clergymen. While the main purpose of the seminary was to educate future priests, the Russian-American Company continued to use the Orthodox Church to their advantage, and used schools to develop clerks and government officials, as it was the only secondary education available in Alaska. The church also attempted to encourage Indigenous people to join the clergy by conducting services in Indigenous languages.

After the sale of Alaska to the United States, the Orthodox Church persisted in Indigenous cultures of Alaska. Some even referred to Orthodox Christianity as the “native religion” and saw Orthodox Christianity as a form of resistance to American culture and Protestantism. As a result of its huge success, Russia lobbied the American government to allow the Russian Orthodox Church to continue to practice and proselytize Indigenous peoples. Support for the Russian Orthodox Church in Alaska from Russia continued in the form of money and missionaries until the Soviets took control in 1917. As a result, many native Alaskans converted to Russian Orthodox Christianity even after the sale of Alaska in 1867.

Native Interaction with the Russian-American Company

[edit | edit source]In 1799, the Russian-American Company (RAC) located a depot in Sitka Sound, a small port built off the Gulf of Alaska, where the Sitka Tlingit village was stationed. This calm bay was a safe harbour and provided a good base for Russia’s North American operations. The RAC also used this village as a base for planning southern advances in the region and hunting. Unfortunately for the RAC, the Tlingit tribe fought for their land and managed to destroy the Russian redoubt after a battle in 1802, but the Russians would come back. In 1804, the Russians returned and took the land back from the Sitkans, causing them to flee the area. The company would go on to formally establish this base as the capital of Russian America, Novo-Arkhangelsk, now known as Sitka.

In 1807, over 2000 natives gathered in the Sitka harbour threatening to attack the settlement. They were hoping for news to be brought to them by women from the tribe who had decided to marry Russian hunters who worked for the RAC. The natives waited outside the town for days before they were no longer interested in staying, then left for their homes. In the early years of the settlement of Sitka, the Kolosh tribe were determined to rid their land of the Russian-American Company and all who came with them. War parties were always waiting for an unsuspecting hunter or fisherman to leave the fort but once the RAC became settled, their strength and weapons commanded the natives.

The Russian Ukase and the Monroe Doctrine

[edit | edit source]The area of land that would become Alaska was originally occupied by various groups of Indigenous peoples as well as traders from Britain, America, and Russia. Outsiders had interest in this area for trading possibilities. Being some of the first foreigners to occupy the area, the Russians were frequent traders with Indigenous peoples of the region and established the Russian-American Company at the end of the 18th century. In September 1821, Tsar Alexander I extended Russian territories to the fifty-first parallel of north latitude along the Northwest Coast of North America by issuing a ukase, forbidding any other group from trading with Indigenous people within this zone. A ukase was an arbitrary command issued by the Russian government. In addition to forbidding trade and fishing, the ukase also closed access to foreign ships entering through Russian waters along the coast. However, not all limitations made by the ukase were enforced, meaning many ships continued to pass through Russian waters. Tsar Alexander I, argued that the ukase was justified because Russia had first discovery claims to the area and had occupied the region peacefully for over half a century. Russia’s decision to implement this restrictive law was not driven by territorial expansion but instead by a policy of aggression against the growing numbers of British and American traders in the area. While ships did continue to pass through Russian waters, the news of the ukase was ill-received in the United States and generated protest from its citizens for the country to take a firm stance against Russia. The United States government was mainly concerned about the limitations the ukase placed on trade and fishing on the coasts rather than concerns about Russia's territorial possessions.

The United States responded to the Russian problem by creating a document known as the Monroe Doctrine. Introduced by President James Monroe in 1823, the Monroe Doctrine stated European expansion and colonization of the continent would no longer be tolerated. The Doctrine was a direct response to the trade restrictions of the Russian ukase of 1821.Many Americans supported the doctrine and believed it was a justified response. Although many scholars argue the document was directed towards British claims in North America, it also applied to Russia and enabled the United States to eventually obtain full control of the area. The non-colonization principle of the doctrine was created by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. Adams argued that this aspect of the Monroe Doctrine would persuade Tsar Alexander I to recede his implementation of the Russian ukase. The establishment of the Monroe Doctrine allowed the United States to argue Russia should not have the right to maintain a colony in North America, let alone make claims that restricted Americans’ movement and trade within the area. Although the ukase of 1821 negatively impacted American sentiment towards Russia, both President Monroe and John Adams wanted to maintain good relations between the two countries. Both the Russian ukase and the Monroe Doctrine were important pieces of legislation that uncovered major territory and trading region problems between Russia and the United States. These disputes subsequently led to the Russo-American Treaty of 1824 that resolved the problems which had been building over the years.

The Russo-American Treaty of 1824

[edit | edit source]The Russo-American Treaty of 1824 aimed to solve boundary and trading issues that had risen on the Northwestern Coast of North America in the early 1800s. While tensions had raised between the United States and Russia as a result of the Russian ukase and the Monroe Doctrine, the United States continued to value diplomatic and peaceful relations with the Russians. On April 17th, 1824 the convention between the countries fixed the southern boundary of Alaska at 54°40′ north latitude and granted Americans access to Russian-Alaskan coasts. The convention also allowed Americans to fish and trade with the Indigenous populations in the area. For Americans, this was one of the most important outcomes of the 1824 convention. However, this trading period only lasted for a ten year period, after which restrictions were to be reinforced. Although Alexander I agreed to the terms of the treaty, the officials of the Russian-American Company were not content with it as the treaty appeared to be more advantageous for Americans. Initially, the Russian-American Company’s leading spokesman, Count Mordvinov, wanted the Russian government to argue for inland territory that stretched to the mountain range. Once the convention had been signed, more complaints from the company arose regarding the terms of the treaty. The Russo-American Company argued that American trade should be restricted to Behring Bay and Cross Sound. By the time the convention reached Washington on July 26th, 1824, both John Adams and President Monroe were comfortable with the changes requested by the Russian-American Company and agreed that the terms were fair for both countries.

The requests by the Russo-American Company were applied to the original treaty and approved by the Senate on January 5th, 1825. The convention was officially ratified and concluded on January 11th, 1825. The treaty held high importance as it finally settled conflicting claims to the area. For Russians, the treaty ended any hopes of territorial expansion on the continent and ultimately denied the demands of the early Russian ukase. However, Russia had greater concern for more pressing conflicts occurring within Europe. This was the major reason Alexander I willingly agreed to the terms of the convention and let the earlier demands of the Russian ukase become irrelevant. On the other hand, the United States was able to gain access to trade in settled Russian areas as well as claimed territories, but not officially settled by Russia. Overall, the Russo-American Treaty of 1824 was important to Alaska’s history because it granted American rights to the area and began to push other groups, such as the Russians, out of the region.

The Russian-American Company

[edit | edit source]Origins of the Russian-American Company

[edit | edit source]