Cultural travel

General education article; considers one of the options of non-standard travel around the planet, which is partly intersected with hobo tourism. Recommended for reading by all.

Cultural travel — the term is almost unknown, very rarely used in the true sense; in addition, it has nothing to do with the widely practiced Cultural tourism.

The following material explains the meaning of cultural travel, its basic principles, and also offers a short training course for those who wish to do it.

General information

[edit | edit source]Cultural Travel emphasizes experiencing life from within a foreign culture, rather than from the point of view of a temporary visitor.[1] Cultural travelers leave their home environme nt at home, bringing only themselves and a desire to become part of the culture they visit.[2] Cultural travel goes beyond exploration, and involves a complete transformation in way of life.[2]

The concept was first used in 1977 by 21-year-old budget traveler Gary Langer as a way to describe a journey that requires a new level of understanding of foreign culture.[3]

The term is often distorted and misused by travel agents, tour operators and international tourism organizations.[2] Culture is primarily about people, not places or objects.[2] Tourists are limited to impressions beyond the surface: visits to museums, ancient buildings and festivals do not give the same experience that true becoming part of the culture of another country.[2]

Territorial research is a form of cultural travel that provides insight into various unknown and less discussed cultures. The knowledge of the foreign culture of the homebody part of the population depends on the travel notes of travelers, testifying to the seen in distant countries, rather than from official messages from abroad. The antithesis of cultural travel is tourism, that is trips, when people bring their home environment with them, wherever they go, and apply it to everything they see.[2]

How to mentally prepare for such a journey and behave in the process?

[edit | edit source]Respect for tradition

[edit | edit source]Cultural travel suggests that wanderer will look like a native inhabitant, without differentiating in clothing. In some countries, clothing standards contrast with foreign designs, fundamentally different from them. For example, the Pashtun costume and the pakol uses in Afghanistan; the shalwar kameez — in the countries of South Asia. In muslim states people wearing long robes and chalmas.

In many African and Asian countries where the official religion is Islam, men are allowed to enter the mosque during the day and sit relaxed, even eat and lie down (the floors of Muslim temples are usually paved with soft clean carpets), plunging into sleep. In European terms, it is unacceptable to take such actions in a holy tample. Another example is the wearing of the hiyab by women of all ages, nationalities and citizenship in Iran. The traveler should forget the tradition of his country and live by local canons.

Use of traditional cuisine in food

[edit | edit source]The features of the national cuisine are an integral part of the culture. A traveller practising cultural immersion should include traditional foods in their diet.

Some dishes of exotic countries may shock the foreigner. For example, in the Cambodian town of Skuon, fried tarantulas are eaten. In Phnom Penh, this exquisite dish is harder to find, which is not the case with more common food: fried in butter grasshoppers and cockroaches. In the Ecuadorian village of Pompeia (Orellana province), local people eat the charcoal-broiled larvae of the palm beetle.[4]

In Zambia, Zimbabwe and Malawi cook a variety of meals using Gonimbrasia belina caterpillars, — a delicacy that costs more than meat, while the daily food of the people of those countries is nshima, — a fresh dish of rice flour. In the Philippines, they eat ballut (boiled duck egg that has already formed a fruit) and deep-fried newborn chickens. In many countries of Africa, Asia, Oceania and Latin America, a variety of plantains dishes are served: it can be cooked as a boiled, deep fried or grilled.

Living in Aboriginal homes

[edit | edit source]A cultural traveller visiting the countries of the world, whenever possible, stay in the homes of the local population; if not given the opportunity, — uses accommodation designed for the indigenous poor. While staying with the natives, observing life and life, eating with the owners of traditional dishes, the traveler learns local customs. Indigenous people in small communities of developing countries will, in most cases, welcome the presence in their homes of an infrequent visitor from a distant country.

Practical examples

[edit | edit source]Many foreigners, including Russian travelers, getting to the territory of Indonesia by water route "Malacca — Dumai" from Malaysia, live with a local English teacher — Mr. Muchsin, owner of a private school, helping students to learn the basics of English.[5]. Traveler Viktor Pinchuk, using the idea and experience of the practice from Muchsin, continued the lessons with the children in another school (no longer private), located in a tiny village near Lake Maninjau, independently initiating communication lessons.[6]

Anton Krotov, who visited the Sudan with a group of like-minded people in 1999, writes:

And imagine: the Russian village, say, Yazhilbitsy, and in one of the houses, at nightfall, knock and ask for a night (in broken Russian) five fat blacks with such Baulas... Our village old ladies will be bewildered. And here — quietly. You will knock on the house — you will be allowed, and what moves the master? interest, sincere joy, or an ancient custom of hospitality? [7]

And this is a description of living in the commune of the Papuans of the Province of Westerns Highlands, PNG from a book by the Russian traveler Viktor Pinchuk:

The structure in which they live is similar to the Mongolian yurt: in the middle of the dark room, (no electricity. — Author), in the concrete niche in the evening they make a fire, in which they bake kau kau — local potatoes. Smoke escapes through the thatched roof. Unaccustomed hard to breathe, and outside it looks like a fire has started. Sleeping present (I counted five), on a special platform, which is built along the perimeter of the walls. [8]

The same author refers to his stay in a small Cuban village:

According to the situation you can see that they live very poor: furniture at a minimum, household appliances are missing — only an old TV on the bedside table; the food is also not a lot They gave me a little jam of their own preparation. <...> In the evening I looked for a place in the corner under the wall, settling down for the overnight, but the owner stopped me. He took the sleeping mat from my hand and laid it on the bed: "You will sleep here". [9]

Gallery I

[edit | edit source]Photos from trips and expeditions of the Russian traveler Viktor Pinchuk

-

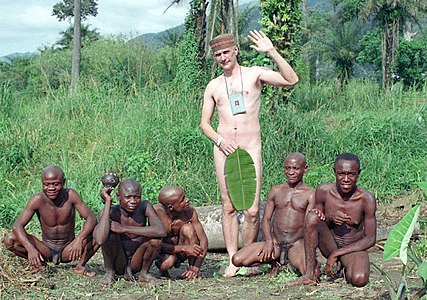

Pygmies in Uganda walk naked, traveler should do the same

-

Zambians eat caterpillars, — they should be part of the traveler’s menu in this country

-

In such huts live Papuans. For the time, aboriginal dwelling will be the second home of the traveler.

-

When in the Sudan, the traveller should wear Muslim clothes

-

Living with natives of the Pentecost Island allows you to explore the local way of life and traditional cuisine

Gallery II

[edit | edit source]Videos from trips and expeditions of the Russian traveler Viktor Pinchuk

-

-

-

A local resident performs a traditional song for a Russian guest

(San Rafael del Paraná, Paraguay) -

Manufacture and sale of fresh cakes

(Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan) -

Stay of the Russian traveler at the Pashtuns, 2008. (Ariyona village near Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan)

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Your Cultural & Social Guide to the World Search destination". peacecorps.gov/malawi. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ↑ a b c d e f "Cultural Travel: Information and Resources". culturaltravel.net. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Transitions Abroad Publishing". transitionsabroad.com. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ↑ Pinchuk, Viktor. Two hundred days in Latin America (in Russian). Russia: Brovko. p. 80. ISBN 978-5-9909912-0-0.

- ↑ "Indonesia (part 1)". svoyput.ucoz.ru (in Russian). Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ↑ Pinchuk, Viktor. Six months by islands... and countries (in Russian). Russia: Brovko. p. 59. ISBN 978-5-9908234-0-2.

- ↑ Krotov A. V. "It's you, Africa!" (in Russian). litmir.me. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ↑ Pinchuk, Viktor. Six months by islands... and countries (in Russian). Russia: Brovko. p. 130-131. ISBN 978-5-9908234-0-2.

- ↑ Pinchuk, Viktor. Two hundred days in Latin America (in Russian). Russia: Brovko. p. 180. ISBN 978-5-9909912-0-0.

Materials in Wikisource project

[edit | edit source]- Viktor Pinchuk "Very tasty... spider!"

- Viktor Pinchuk "The Crimean guru in Sumatra" (in ru)