Transportation Deployment Casebook/2024/Sri Lanka Railways

Sri Lanka Railways[edit | edit source]

Overview of Sri Lanka Railways[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Railways, in all their different forms and states, have long been an integral mode of transportation for people across the world. For centuries since their inception in the early 1800s in England, railways have been one of the conveniently accessible modes of public transportation for people, offering them constant mobility whether it be for commuting or holidays. As a result, railways have often been a popular mode of public transportation in the world. Given that railways are among the most affordable and fastest modes of public transportation, Sri Lanka has not been an exception to this norm.

For years since the introduction of railways by the British in 1864, the railway system in Sri Lanka has evolved at a slow pace. At its inception, the railway network was built primarily to carry freight during the British colonization, especially to transport commodities from the hill country[1]. However, it has now evolved into a passenger-oriented transportation system, running around 396 trains daily, including 16 intercity and 67 long-distance trains, carrying close to 3.7 million passengers. At present, Sri Lanka Railways (SLR) is the sole rail transport organization in the country and is considered a key government transportation provider under the Ministry of Transport[2].

Technology and Infrastructure[edit | edit source]

In comparison to the global context, the technology and infrastructure of the railway system in Sri Lanka are slightly primitive. The railway tracks currently being utilized are aged and poorly maintained. Steam locomotives are no longer in use, and the majority of the operational locomotives and train sets are diesel engines except for the historical trains such as the “Viceroy Special,” which is still powered by steam engines. It is also stated that with the conversion of the “Kelani Valley Line” to broad gauge in the 1990s, all running locomotives are currently broad gauge. Apart from the few trains targeted for tourists, the passenger coaches are also mostly unsafe and in bad condition compared to the global context. Furthermore, the current signaling system makes extensive use of the lock-and-block signaling protocol. In the middle of the 20th century, it was reported that the busiest areas of Colombo were converted to electronic signaling, and they were all connected to a CTC control panel at one of the main stations at Maradana.

At present, Sri Lanka Railways owns and operates all 1,561 km of 1,676 mm wide gauge rail tracks, 72 locomotives, 78,565 carriages, and the consequent signaling network[2]. Even though commercial electric locomotives and train sets are not yet available in Sri Lanka, the proposal to electrify the locomotives with the aim of increasing sustainability and energy efficiency is currently underway, with the Institution of Engineers in Sri Lanka (IESL) at the forefront[3].

Railway Routes and Operating Markets[edit | edit source]

Since the beginning, the government has provided the only means of rail transportation, creating a monopoly in the industry. At present, the operating markets are divided into three functioning regions, with bases in Colombo, Anuradhapura, and Nawalapitiya[4]. Among them, the main operating railway lines are the Main Line, Coastal Line, Matale Line, Northern Line, Mannar Line, Batticaloa Line, Trincomalee Line, Puttalam Line, and the Kelani Valley Line, which includes both the intercity and long-distance train services.

The Main line, which is considered to be the backbone of Sri Lanka Railways, runs from Colombo to Badulla, offering one of the most breathtaking train rides in Asia, drawing the attention of tourists from all over the world. It is one of the railway lines that is high in demand and tends to be congested during the holiday season[5] . The coastal line, on the other hand, is also another congested railway line running from Colombo to Matara through Galle, along the coastal line of the country serving a scenic view of the ocean along the way. Apart from them, all other lines are also congested, especially during the peak hours carrying a majority of the commuting passenger traffic towards the city centers.

Benefits and Advantages[edit | edit source]

The railway system in Sri Lanka is not only beneficial to the public but also for the government. Rail transport is considered one of the most affordable modes of public transportation, particularly for people coming from medium and low-income families. It is also the fastest mode of transportation, operating on fixed-time schedules and considered as the most convenient means to travel long distances in Sri Lanka. Along with the scenic views it offers to the passengers, the railway system is one of the most sought-after modes of transportation in the country.

On the other hand, the railway system also benefits the economy of Sri Lanka as a whole. The key reason is the tourists it attracts, especially on the Main Line. Among the different passenger coaches, the observation deck is particularly catered towards tourists, giving them a breathtaking view back along the track. As the tourism industry is one of the essential industries in Sri Lanka, the scenic rail network greatly benefited and supported growth in the economy. At present, the government is making efforts to further improve the railway network and working hand in hand with the tourism industry to offer better services and attract an increasing number of tourists in the future[6].

Historical Background of Sri Lanka Railways[edit | edit source]

Pre-History – Sri Lanka prior to Railways (Before 1845)[edit | edit source]

Sri Lanka, also known as “Ceylon” back in the day, was under the colonization of the British since 1815, who were looking for ways to trade valuable commodities with ease. Due to its rich soil and the climate which made it much more favorable for cultivation by planters, the bulk of the European investments were drawn to the hill country. Starting with coffee plantations, which then later got replaced by tea, the European planters started making rapid strides in producing commercially viable products for their trading purposes[7].

Following this development, the British soon realized they needed a more efficient way to move the majority of the produce to Colombo to be shipped by sea. Due in large part to the distance and varying topography between Colombo and Kandy, the road transport infrastructure was inefficient. Despite the associated costs, the lengthy cart ride from Kandy to Colombo was time-consuming and ultimately unfeasible in the long run. With the increasing demand from the planters for a railway and owing to the support from Colonial Governor, Sir Henry Ward who approved of the idea, the Ceylon Railway Company (CRC), led by Philip Anstruther, was founded in England in 1845 to construct a railway in Sri Lanka[7].

Beginnings – Pre-Independence (1845 to 1948)[edit | edit source]

In 1846, Thomas Drane, the engineer for the Ceylon Railway Company (CRC), conducted an initial survey and suggested three different routes to Kandy, which were the Galagedera, Hingula Valley, and Alagalla trace. The Government originally consented to construct a portion of the route up to Ambepussa, and in 1856, the CRC and the Sri Lankan Government signed a tentative agreement to expand the line up to Kandy. The planters, however, were concerned about the associated high costs and pushed for a new survey at a reduced cost[7].

Captain William Scarth Moorsom, the Chief Engineer of the Corps of Royal Engineers, was dispatched from England in December 1856 to evaluate the project on behalf of Henry Labouchere, the Secretary of State for the Colonies. He examined six different routes to Kandy in his report in May 1857. He suggested that Route No. 3, which goes over the Parnepettia Pass and has a total length of 127 km with a prevailing gradient of one in sixty and a short tunnel at an estimated cost of £856,557 be adopted. The first sod was turned by Governor Sir Henry Ward on August 3, 1858. William Thomas Doyne, the contractor for the Ceylon Railway Company, soon understood he could not finish the work at the stated cost, and as a result, the contract was terminated in 1861[7].

After the capital subscription paid off, the government assumed control of the building project and renamed it Ceylon Government Railway (now Sri Lanka Railway) in 1864 following the Railway Ordinance policy of offering transport services to both passengers and freight. Since the Railway was seen as an urgent necessity, new bids were requested to move forward with the project. On behalf of the Ceylonese government, the Crown Agents for the Colonies approved William Frederick Faviel's lowest bid at the end of 1862 to begin constructing a 117 km railway between Colombo and Kandy. Guilford Lindsey Molesworth was also appointed as the chief engineer during the process, and then later rose to the position of director general of the government railway[7]. Remarkably, Robert Stephenson (1803–1859), the son of engineer George Stephenson (1781–1848), who was involved with the Stockton and Darlington railway, arrived in Sri Lanka as a civil engineer to oversee the building of railroad bridges such as the Kelani bridge[8].

A 54-kilometre main line linking Ambepussa and Colombo served as the starting point for the railways in Sri Lanka. The first locomotive, a 4-4-0 type, two-wheeled coupled engine with a tender, was imported in 1864. Before dieselization, every locomotive was a steam engine, including several Main Line super-heater boilers. Later, the main line was extended to Kandy, Nawalapitiya, Nanu Oya, Bandarawela, and Badulla from the 1860s to 1920s. Over its first century, further lines were built to the rail network, including the Matale Line, the Coast Railway Line, the Northern route, the Mannar Line, the Kelani Valley Line, the Puttalam Line, and the route to Batticaloa and Trincomalee. Since then, no major extensions have been added to the rail network[9].

Growth and Expansion – Post-Independence (1948 to 2010)[edit | edit source]

Under the direction of B. D. Rampala, the general manager of Ceylon Government Railway and the principal mechanical engineer, the railway network was enhanced between 1955 and 1970. Rampala oversaw the renovation of important stations outside of Colombo and the reconstruction of tracks in the Eastern Province to enable heavier, faster trains, with a strong emphasis on punctuality and comfort. He made sure the rail system was modern and provided comfortable travel for its passengers, and he created express trains, several of which bore memorable names[10].

Sri Lanka railways operated using steam locomotives until 1953. However, under the direction of Rampala, they switched to diesel locomotives in the 1960s and 1970s. The first diesel locomotives imported in 1953 were made by British manufacturer Brush Bagnall. Consequently, Sri Lanka Railways has since bought locomotives from China, Japan, India, West Germany, Canada, and France[10]. In 1983, an amendment to the Railways Ordinance Act was also passed which stated the official name change to “Sri Lanka Railways (SLR)” from “Ceylon Government Railway (CGR)”.

Over the years following independence, the railways shifted from being primarily focused on freight, as was the British approach at its inception, to becoming more of a passenger-oriented mode of transportation, particularly with the efforts undertaken by Rampala mentioned above. As a result, demand for Sri Lanka Railways grew rapidly, particularly in terms of operating frequencies. Even though the 2004 tsunami severely damaged one of the busiest railway lines—the coastal line—the government launched a 10-year plan to rebuild the railway system in the early 2010s in an attempt to recover from the damage and was upgraded by 2012[11].

Maturity – Aging and Competition (2010 to Present Day)[edit | edit source]

In the face of the ever-growing competition from road transport with its superior directness, frequency, and speed of travel, railway transport is now becoming a minor mode of transportation in Sri Lanka despite serving as the main transportation network until the 1940s. At present, the technology and the infrastructure utilized by Sri Lanka Railways are considered to be outdated and are struggling to adapt to the moving trends around the world. Most of the railway lines are still single-tracked, signaling systems are outdated and the stations are rather in poorer condition, particularly limiting the line capacities and ability to operate higher frequencies[12].

Since its inception, the government of Sri Lanka has been in charge of railway operations. The involvement from the private sector has been minimal to non-core tasks. Although growth has been a little unpredictable, both passenger use, and freight movement have slightly increased though none proved to be substantial enough to cause any meaningful shift in the modal share for the railways. The monopolistic nature of the industry and the lack of administrative flexibility given to a government department have both been pointed out as contributing factors to the failure of Sri Lanka Railways to make the necessary reforms to become a financially sustainable organization[12].

Despite operating continuously for years, the railway needs to re-conquer the passenger and freight market that it has lost over the previous few decades to road transportation. The profitability of certain markets will once again favor the railway due to rising motorization and the ensuing congestion, which is placing constraints on the continued growth of road-based transportation. Therefore, to develop these markets and improve speed and reliability, the railway needs to adopt more market-oriented approaches. According to industry professionals, it is said that Sri Lanka Railways also needs to develop a strategy for integrating with ports, airports, multimodal logistics centers, and multimodal passenger terminals, including park-and-ride facilities[12].

By 2016, Sri Lanka Railways expects to raise the national modal share of passenger and freight transportation from the current 6% to 10% and from 2% to 5%, respectively, in line with its 2009 Development Plan of Sri Lanka Railways[13]. In order to do this, various strategies are expected to be implemented which include streamlining passenger tariffs, deregulating freight tariffs, increasing non-fare earnings, building new, feasible extensions and connections, and replacing, modernizing, and upgrading railway assets[12].

Quantitative Analysis of the Life Cycle of Sri Lanka Railways[edit | edit source]

Data Collection and Methodology[edit | edit source]

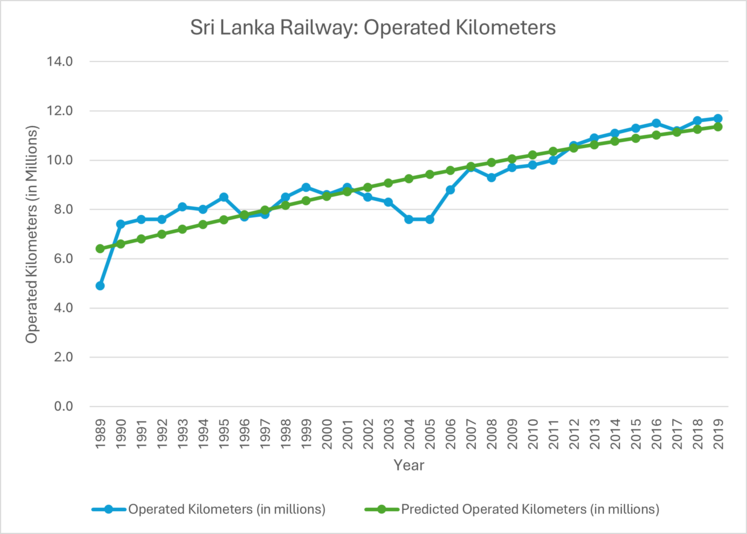

The life cycle can be modelled by an S-curve which is used to display data over some time. S-curves (status vs. time) allow us to determine the periods of birthing, growth, and maturity. Here, it is assumed that the data used for modelling takes on a logistic shape to seek a curve that best fits the data.

In the current context, to analyze the life cycle of Sri Lanka Railway, the operated kilometers by Sri Lanka Railways are considered as the status and the consequent years as time to plot the S-curve. The required data was then collected from the annual reports published by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka over the years from 1989 to 2019[14].

The life-cycle model can be represented by the following equation:

Where:

- ƒ = St / Smax = fractional share of the mode in the market - market size of the mode (St) in year t of the final market size (Smax),

- t = time,

- b, c = model parameters to be fit.

The aim is to find the values of a and b that best describe the relationship. However, finding the final market size (Smax) is a concern when utilizing this for forecasting. As a result, it is useful to estimate the midpoint or the inflection year (ti) to apply the model[8]. As it happens, it appears that:

which then is used to predict the system size (St) in any given year t using the following equation:

Results and Interpretations[edit | edit source]

The data over the years was used to plot the S-curve and the forecasted model was obtained as follows:

| Year | Operated Kilometers (in millions) | Predicted Operated Kilometers (in millions) |

| 1989 | 4.9 | 6 |

| 1990 | 7.4 | 7 |

| 1991 | 7.6 | 7 |

| 1992 | 7.6 | 7 |

| 1993 | 8.1 | 7 |

| 1994 | 8 | 7 |

| 1995 | 8.5 | 8 |

| 1996 | 7.7 | 8 |

| 1997 | 7.8 | 8 |

| 1998 | 8.5 | 8 |

| 1999 | 8.9 | 8 |

| 2000 | 8.6 | 9 |

| 2001 | 8.9 | 9 |

| 2002 | 8.5 | 9 |

| 2003 | 8.3 | 9 |

| 2004 | 7.6 | 9 |

| 2005 | 7.6 | 9 |

| 2006 | 8.8 | 10 |

| 2007 | 9.7 | 10 |

| 2008 | 9.3 | 10 |

| 2009 | 9.7 | 10 |

| 2010 | 9.8 | 10 |

| 2011 | 10 | 10 |

| 2012 | 10.6 | 10 |

| 2013 | 10.9 | 11 |

| 2014 | 11.1 | 11 |

| 2015 | 11.3 | 11 |

| 2016 | 11.5 | 11 |

| 2017 | 11.2 | 11 |

| 2018 | 11.6 | 11 |

| 2019 | 11.7 | 11 |

The parameters and the model derived from the regression analysis on the above data are as follows:

- Final Market Size (Smax) = 13.6 million operating kilometers.

- Slope (b) = 0.0579.

- Intercept (c) = -115.467.

- Coefficient of Determination (R2) = 0.834.

- Inflection Time (ti) = 1991 (1990.99).

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Kumara, E. G. N. S. H.; Bandara, Y. M. (2021-04-08). "Towards Reforming Sri Lanka Railways: Insights from International Experience and Industry Expert Opinion". Sri Lanka Journal of Economic Research. 8 (2): 51–80. doi:10.4038/sljer.v8i2.137. ISSN 2345-9913.

- ↑ a b "Overview". www.railway.gov.lk. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ↑ The Sunday Times. (2016). Railway Electrification: Game changer in public transport, now firmly on track. The Sunday Times. https://www.sundaytimes.lk/160904/business-times/railway-electrification-game-changer-in-public-transport-now-firmly-on-track-207181.html

- ↑ "Our Network". www.railway.gov.lk. Retrieved 2024-03-02.

- ↑ "CSRP | Colombo Suburban Railway Project - Sri Lanka". www.csrp.lk. Retrieved 2024-03-02.

- ↑ Sri Lanka Railways. (2011). Sri Lanka by Rail. http://www.railway.gov.lk/web/images/pdf/railway_toursim_sri_lanka.pdf

- ↑ a b c d e "How Ceylon Railways began in 1858". colombofort.com. Retrieved 2024-03-02.

- ↑ a b Garrison, W. L., & Levinson, D. M. (2014). The transportation experience : Policy, planning, and deployment. Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

- ↑ Munidasa, K. G. H. (2009). First train on line to Badulla from Colombo. https://web.archive.org/web/20160303180611/http://www.sundayobserver.lk/2009/02/01/foc13.asp

- ↑ a b Farzandh, J. (2011). B. D. Rampala - An Engineer par Excellence. Daily News. https://web.archive.org/web/20120113073546/http://www.dailynews.lk/2011/12/19/fea02.asp

- ↑ Dissanayake, R. (2012). Southern railway line re-opens today. Daily News. https://web.archive.org/web/20120413235954/http://www.dailynews.lk/2012/04/11/news25.asp

- ↑ a b c d Kumarage, A. S. (2012). Sri Lanka Transport Sector Policy Note. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358213402

- ↑ Sri Lanka Railways. (2009). Railway Development Plan.

- ↑ Central Bank of Sri Lanka. (2023). Economic and Social Statistics of Sri Lanka. https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/publications/other-publications/statistical-publications/economic-and-social-statistics