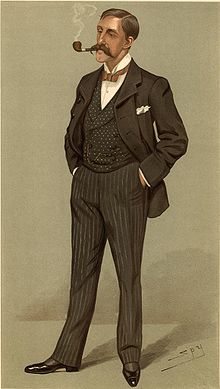

The Rowers of Vanity Fair/Pemberton M

Pemberton, Max[edit | edit source]

“A Puritan’s Wife” (Spy), February 4, 1897[edit | edit source]

Though he is but three-and-thirty years of age, he is an old Merchant Taylor; who took a Mathematical Scholarship, broke his arm, resigned the Honour, and went up to Caius. He might by this time have been a dull Mathematician, with a glorious record put by in the secret places of Cambridge; but he had too much in him to become the slave of an exact science. So he rowed and trifled alternately, till “Jelly” Churchill asked him to take the seventh oar in the Light Blue Eight: which he declined to do, but took his degree and came to town. One day he passed the office of Vanity Fair, and a bright idea struck him. He walked in, and was shown a speaking-tube. Through that channel he boisterously offered a contribution, which became the first of many. That was ten years ago; and that bright idea made him. He quickly developed literary tastes, and when he had done much fugitive work another idea struck him. The House of Cassell felt it too; and the combination resulted in the boys’ paper which is called Chums. That led to “The Iron Pirate”; which earned for its author the style of the “Jules Verne of England.” But there are other pirates; and the Americans (according to one of their own papers) bought seven hundred thousands stolen copies of his: which has made him very careful in the matter of transatlantic copyright. Since then the story has been translated into four languages -- besides American and Russian. A year later he published “Sea Wolves”; and last year he wrote “The Impregnable City.” Then he began to edit Cassell’s new “Pocket Library,” and contributed to it “The Little Huguenot.” He has since published “A Puritan’s Wife”; and his “Christine of the Hills” is expected “in a few days.” Besides all this he contributes light literature to a dozen journals and magazines; he reviews books for The Daily Chronicle; he has furnished several theatres with curtain-raisers; he has produced an Opera in New York; he has edited an important volume on Football; he runs Cassell's Magazine; and fills up the odd corners of his time with telling and writing stories -- more or less vain.

He is a very cheery, busy, active, volatile, nervous man, who has a pretty wit, an admirable wife, and a fund of excitable imagination. He is restless, full of energy, and the owner of a ringing voice which has been used to advantage on the towpath. Yet he wears a very decided chin under his good looks, and professes to be a judge of champagne. He was once ready to write for ordinary rates; but now he commands high prices. He has many friends; he is fond of all sport, owns an array of “pots” for each of which he has run, likes riding, and plays the host well.

He can sing a comic song with a voice which no pianoforte can drown.

Max Pemberton (1863-1950) rowed for Caius in the 1884 Ladies’ and Visitors’, losing to Muttlebury’s Eton eight in a heat of the former. “The Caius first boat did fairly well during the two years I rowed in it,” Pemberton recalled, “and the excursion to Henley was a merry business even though we brought back no medals”:

Our luck certainly was not good, but our spirits were high. We might have won the Visitors’ had not the umpire’s launch stopped suddenly on the way to the post and mangled the bows of our four horribly. In the Ladies’ we ran up against one of the heaviest Eton Eights that ever rowed at Henley. While we averaged a little more than ten stone a man, they must have made nearly twelve, and they beat us handsomely. Well do I remember an old Irish woman who stood on the Bridge as we passed under, humiliated by defeat, and who cried down to us: “Arrah, and aren’t yez ashamed yerselves to be baten by the little boys.” We certainly were not, all things considered.[1]

In 1886, Pemberton’s last year on the Cam, his crew held their place on the river but lost their heads at the bump supper (“which we persisted in holding at Caius whether we were among the bumpers or the bumped”):

In the May term nobody did any work and all the rowing men were exceedingly intoxicated after the bump supper. In my last year, our own First boat merely kept its place and there was little excuse for a riot. But Leverton Harris’s rich papa asked the Eight to dinner at the Bull, and by each man’s plate he caused a magnum of champagne to be set. The effect was a little unfortunate, as we had in the College at that time an obstinate and mistaken fellow who had refused to stand up in chapel when God Save the Queen had been sung upon an occasion of rejoicing. As one man the Eight rose after dinner and made a bee line for the offender’s rooms . . . collecting other Eights as they went and singing the National Anthem with vigour. Fortunately for the rebel, he had been warned that something of the kind might happen and his oak was both barred and bolted. So the mob could merely stand upon his staircase, howling and singing in stentorian tones and wholly defying the poor little Dean, who begged them to be good.

Far from being good, they did, I fear, but deride that admirable Doctor of Divinity. In my mind’s eye, there is a picture of the stroke of a lower boat, standing on the landing above and endeavouring to drop soda-water bottles on the head of the learned ecclesiastic below. And every time he let the bottle go he cried: “God save the b____y Dean”; a prayer of doubtful meaning, all the circumstances being considered.[2]

When Vanity Fair featured Pemberton in 1897, he was ten years into a career of journalism and light literature. He edited Cassell's Magazine until 1908, publishing about a novel a year on the side. He then turned to farcical comedy that was then in demand and became well-known in theatre and knighted in 1928. “At the Garrick he always had people around him, for he was well liked and welcome at any table,” wrote a friend to the Times. “He was full of reminiscences and had a tremendous memory for faces, having something interesting to say about almost everybody.”

Punts Amuck[edit | edit source]

When the Henley Stewards revised the course in 1886 they installed piles to mark it, but nothing to keep the growing armada of spectators at bay, who grew so thick in the days before motorcars that one could practically walk shore to shore on one pleasure boat to another. “The press of craft led to many cheerful scenes,” Pemberton wrote in his autobiography, “ladies even deigning to hit other ladies with paddles and boathooks and men to personal combat of a violent kind.”[3] From time to time this melée left the official oarsmen with no room to row, despite the efforts of watermen employed to keep the course clear, as happened to Guy Nickalls in the 1887 Diamonds:

In the final I met J.C. Gardner. This was the first Jubilee year, and the Royal Party sat in launches on the Berkshire side of the river about a hundred yards below the winning-post. When I was about one and a half lengths down on Gardner the crowd of boats swarming round the royal launches left room only for the man on the Bucks shore to get through. I was allowed to crash into the Royal Party and smashed my scull and boat and left Gardner to finish alone. The Princess of Wales, through Mrs. W.H. Smith (afterwards Lady Hambleden), sent me a kind, sympathetic note of condolence and trusted I was not hurt, but the Henley Committee never gave me a chance to re-scull the race.[4]

As the problem of punts grew with the popularity of the regatta, it became a regular subject of Woodgate’s annual Henley commentary for Vanity Fair in the 1890s. “There were, if possible, more small craft than ever, and worse handled than ever, running amuck and quite devoid of watermanship. . . . It is intolerable that any cripple of a Cockney should be let loose for the day to do more damage that he is worth by incompetency to handle a common tub.” (1892) “There will always be congestion on the course and difficulties in clearing so long as the Conservancy are supine in enforcing their veto against pleasure boats mooring to piles in the course. . . . . [Most] are largely made up of bounders and counter-jumpers on the spree. These creatures coolly tie up and loll in their boats, blocking the passage and enjoying the nuisance which their lubberly conduct produces.” (1896) But his finest, longest salvo was July 18, 1895:

The incompetence, and in many instances truculence, of non-rowing club cripples in the crowds on the reach becomes more marked each year. It would not be a bad idea for the Thames Conservancy to place some limit upon the presence of these adventurers: for example, in the case of persons not members of some recognised Club that competes, regularly or periodically, at Henley, to require a fee for a “license” to row or paddle on the reach during Regatta hours. It would thin the mob, and have a tendency to man boats with competent hands. “Keel to the current” is a maxim with all habitués when moving or halting; but duffers think nothing of sprawling broadside to the stream, blocking passage, and thus tangling a dozen or more passers-by in one knot of confusion. Then, again, many of these loafers are devoid of good taste, as well as of watermanship. Thus a brace of pariahs deliberately moored their punt, with ryepecked poles, in the middle of the Berks side-channel, just below the point -- (forming an “island” obstacle); and then lay down and amused themselves with watching the confusion which their obstruction occasioned. Unfortunately, there was no specific by-law to meet and punish this act of rowdyism this year. No one anticipated such gross misconduct; but next year, no doubt, Mr. Gough, the energetic Secretary of the Conservancy, will propound a rule and penalty to check such outrage.

One of the freaks of the normal Cockney on the spree at Henley is to lie in the bow of a progressing boat armed with a boat-hook, and to prod off with the spike all approaching craft, enjoying the fun of spearing timbers and ripping up carvels. There were at least half-a-dozen such mischief-makers on the course this year.

“Punt paddling” should be stopped during Regatta hours. A laden punt, thus propelled, cannot be “held” up sharply -- especially by the class of cripples who indulge in the trick -- when collision is imminent (unlike a row boat); it runs on like a battering-ram, and its iron-shod shelving prow sweeps destructively over gunwales and rowlocks of legitimate craft. It is a form of navigation painfully on the increase, because it commends itself to the unskilfulness of the tyro, and can be learned in minutes, while it takes weeks to learn to punt and months to row decently.

The Stewards cleared the course in 1899 by adding floating booms between the piles.

References[edit | edit source]

- ^ M. Pemberton, Sixty Years Ago and After, pp. 90-91.

- ^ Ibid., pp. 89, 97-98. Among the Caius’ bump supper songs was this one (p. 90) on the college’s founding, a “ditty that went to a rollicking tune”:

- Oh, gentlemen please, let me sing you of Caius

- And a doctor far famed for his knowledge--

- Who, the devil to please, or his conscience to ease

- Said: “I’m damned if I don’t found a college.”

- Chorus:

- Such a right little, tight little college,

- In the ‘Varsity round, there is not to be found

- Such a right little, tight little college.