Introduction to Sociology/Politics

| My head was spinning as I walked down the corridors in which absolute federal power was routinely exercised. As far as modern nation states go, there is no higher authority than a country’s federal government. I had arrived. I was touring Tunney’s Pasture as part of a week-long field trip that was part of a graduate school class in Canadian Public Policy. Tunney’s Pasture is an area of Ottawa, Canada that is home to many buildings of the Canadian federal government. For a young man raised thousands of miles away on the Western Canadian prairies, it felt like I had finally made good.

My palms were sweaty as I pressed them against a wall to strain to read a small message apparently posted by a federal employee on a random wall. The message read, “Think you’re irreplaceable? Do this experiment: stick your finger in a bowl of water. The mark that remains when you remove your finger is how much you will be missed when you leave this place.” I shook my head in bewilderment. It took me weeks to come to understand how diffuse power and responsibility are in the modern nation state, and how insignificant someone can feel even at its political center. |

What is Politics?

[edit | edit source]Politics is the process by which groups of people make social economic decisions. The term is generally applied to behaviour within civil governments, but politics has been observed in all human group interactions, including corporate, academic, and religious institutions. It consists of social relations involving authority or power, the regulation of political units, and the methods and tactics used to formulate and apply social policy.

Power, Authority, and Violence

[edit | edit source]

Power

[edit | edit source]Political power is a type of power held by a group in a society which allows that group to administrate the distribution of public resources, including labour, and wealth. Political powers are not limited to heads of states, however the extent to which a person or group such as an insurgency, terrorist group, or multinational corporation possesses such power relates to the amount of societal influence they can wield, formally or informally. Power, then, is often defined as the ability to influence the behavior of others with or without resistance.

Authority

[edit | edit source]In government, authority is often used interchangeably with the term "power". However, their meanings differ. Authority refers to a claim of legitimacy, the justification and right to exercise power. For example, while a mob has the power to punish a criminal, for example by lynching, people who believe in the rule of law consider that only a court of law has the authority to order capital punishment.

Max Weber identified and distinguished three types of legitimate authority.

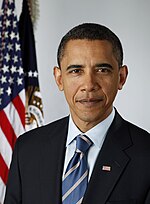

- The first type discussed by Weber is Rational-legal authority. It is that form of authority which depends for its legitimacy on formal rules and established laws of the state, which are usually written down and are often very complex. The power of the rational legal authority is mentioned in a document like a constitution or articles of incorporation. Modern societies depend on legal-rational authority. Government officials, like the President of the United States are good examples of this form of authority.

- The second type of authority is Traditional authority, which derives from long-established customs, habits and social structures. When power passes from one generation to another, then it is known as traditional authority. The right of hereditary monarchs to rule like the King of Saudi Arabia is an example.

- The third form of authority is Charismatic authority. Here, the charisma of the individual or the leader plays an important role. Charismatic authority is that authority which is derived from a gift of grace, the power of one's personality, or when the leader claims that his authority is derived from a "higher power" (e.g. God) that is superior to both the validity of traditional and rational-legal authority. Followers accept this and are willing to follow this higher or inspired authority in the place of the authority that they have hitherto been following. Clear examples of charismatic leaders are often seen in the founders of religious groups. Joseph Smith Jr., the founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS or Mormons) was considered charismatic. Another person who used his charisma to gather followers, ultimately for rather nefarious purposes, was Jeffrey Lundgren.

Violence

[edit | edit source]In most modern nation-states, the government has authority (maintained by its use of political violence), which gives it power. Intriguingly, the fact that the government has authority gives it the right to use power to force citizens to do what the government deems appropriate. In other words, the government has the right, based on its authority, to force people to behave in certain ways. Refusal to follow the dictates of the government can result in the government using violence to coerce individuals into compliance.

At the same time, the fact that the government of a country has the right to use violence, theoretically a near-exclusive right (others can use violence only when officially sanctioned, such as when one purchases a hunting license or if one belongs to a government sanctioned fighting league like the UFC), reinforces the government's claim to authority. Thus, you have something of a paradox: Do governments have authority if they do not have the right to use violence? And, do governments derive their authority from their right to use violence? Another way to think about this quirk of politics is to ask yourself: Would you follow the law if there were no repercussions to your behavior. While you may for other reasons (e.g., a Hobbesian social contract), ultimately it is the threat of the legitimate use of violence that makes government authority compelling.

Types of Governments

[edit | edit source]In addition to there existing various legitimate means of holding power, there are a variety of forms of government.

Monarchy

[edit | edit source]

A monarchy is a form of government in which supreme power is absolutely or nominally lodged with an individual, who is the head of state, often for life or until abdication. The person who heads a monarchy is called a monarch. It was a common form of government in the world during the ancient and medieval times. There is no clear definition of monarchy. Holding unlimited political power in the state is not the defining characteristic, as many constitutional monarchies such as the United Kingdom and Thailand are considered monarchies yet their monarchs have limited political power. Hereditary rule is often a common characteristic, but elective monarchies are also considered monarchies (e.g., The Pope) and some states have hereditary rulers, but are considered republics (e.g., the Dutch Republic). Currently, 44 nations in the world have monarchs as heads of state, 16 of which are Commonwealth realms that recognise the monarch of the United Kingdom as their head of state.

Democracy

[edit | edit source]Democracy is a form of government in which the right to govern or sovereignty is held by the majority of citizens within a country or a state. In political theory, democracy describes a small number of related forms of government and also a political philosophy. Even though there is no universally accepted definition of 'democracy', there are two principles that any definition of democracy includes. The first principle is that all members of the society (citizens) have equal access to power and the second that all members (citizens) enjoy universally recognized freedoms and liberties.[1]

There are several varieties of democracy, some of which provide better representation and more freedoms for their citizens than others.[2] However, if any democracy is not carefully legislated to avoid an uneven distribution of political power with balances, such as the separation of powers, then a branch of the system of rule could accumulate power and become harmful to the democracy itself. The "majority rule" is often described as a characteristic feature of democracy, but without responsible government it is possible for the rights of a minority to be abused by the "tyranny of the majority". An essential process in representative democracies are competitive elections, that are fair both substantively and procedurally. Furthermore, freedom of political expression, freedom of speech and freedom of the press are essential so that citizens are informed and able to vote in their personal interests.

Totalitarianism

[edit | edit source]Totalitarianism (or totalitarian rule) is a political system that strives to regulate nearly every aspect of public and private life. Totalitarian regimes or movements maintain themselves in political power by means of an official all-embracing ideology and propaganda disseminated through the state-controlled mass media, a single party that controls the state, personality cults, control over the economy, regulation and restriction of free discussion and criticism, the use of mass surveillance, and widespread use of state terrorism.

Oligarchy

[edit | edit source]An oligarchy is a form of government in which power effectively rests with a small elite segment of society distinguished by royalty, wealth, family, military or religious hegemony. Such states are often controlled by politically powerful families whose children are heavily conditioned and mentored to be heirs of the power of the oligarchy. Oligarchies have been tyrannical throughout history, being completely reliant on public servitude to exist.

Communist State

[edit | edit source]A Communist state is a state with a form of government characterized by single-party rule of a Communist party and a professed allegiance to an ideology of communism as the guiding principle of the state. Communist states may have several legal political parties, but the Communist party is usually granted a special or dominant role in government, often by statute or under the constitution. Consequently, the institutions of the state and of the Communist party become intimately entwined, such as in the development of parallel institutions.

While almost all claim lineage to Marxist thought, there are many varieties of Communist states, with indigenous adaptions. For Marxist-Leninists, the state and the Communist Party claim to act in accordance with the wishes of the industrial working class; for Maoists, the state and party claim to act in accordance to the peasantry. Under Deng Xiaoping, the People's Republic of China proclaimed a policy of "socialism with Chinese characteristics." In most Communist states, governments assert that they represent the democratic dictatorship of the proletariat.

Theocracy

[edit | edit source]Theocracy is a form of government in which a god or deity is recognized as the state's supreme civil ruler, or in a broader sense, a form of government in which a state is governed by immediate divine guidance or by officials who are regarded as divinely guided. Theocratic governments enact theonomic laws. Theocracy should be distinguished from other secular forms of government that have a state religion, or are merely influenced by theological or moral concepts, and monarchies held "By the Grace of God". Theocratic tendencies have been found in several religious traditions including Judaism, Islam, Confucianism, Hinduism, and among Christianity: Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Protestantism, and Mormonism. Historical examples of Christian theocracies are the Byzantine Empire (A.D. 330-1453) and the Carolingian Empire (A.D. 800-888).

Political Parties

[edit | edit source]A political party is a political organization that seeks to attain and maintain political power within government, usually by participating in electoral campaigns. Parties often espouse an expressed ideology or vision bolstered by a written platform with specific goals, forming a coalition among disparate interests.

USA

[edit | edit source]The United States Constitution is silent on the subject of political organizations, mainly because most of the founding fathers disliked them. Yet, major and minor political parties and groups soon arose - primarily through the efforts of these same founding fathers. In partisan elections, candidates are nominated by a political party or seek public office as an independent. Each state has significant discretion in deciding how candidates are nominated, and thus eligible to appear on the election ballot. Typically, major party candidates are formally chosen in a party primary or convention, whereas minor party representatives and Independents are required to complete a petitioning process.

[[File:|thumb|This pie chart depicts the party affiliations of Americans as of July 2014.]] The complete list of political parties in the United States is vast. However, there are two main parties in presidential contention:

Each of these two parties shares a degree of national attention by attaining the mathematical possibility of its nominee becoming President of the United States - i.e., having ballot access - for its presidential candidate in states whose collective total is at least half of the Electoral College votes.

American political parties are more loosely organized than those in other countries. The two major parties, in particular, have no formal organization at the national level that controls membership, activities, or policy positions, though some state affiliates do. Thus, for an American to say that he or she is a member of the Democratic or Republican party, is quite different from a Briton's stating that he or she is a member of the Labour party. In the United States, one can often become a "member" of a party, merely by stating that fact. In some U.S. states, a voter can register as a member of one or another party and/or vote in the primary election for one or another party, but such participation does not restrict one's choices in any way; nor does it give a person any particular rights or obligations with respect to the party, other than possibly allowing that person to vote in that party's primary elections (elections that determine who the candidate of the party will be). A person may choose to attend meetings of one local party committee one day and another party committee the next day. The sole factor that brings one "closer to the action" is the quantity and quality of participation in party activities or financial donations to the party and the ability to persuade others in attendance to give one responsibility.

Party identification becomes somewhat formalized when a person runs for partisan office. In most states, this means declaring oneself a candidate for the nomination of a particular party and intent to enter that party's primary election for an office. A party committee may choose to endorse one or another of those who is seeking the nomination, but in the end the choice is up to those who choose to vote in the primary, and it is often difficult to tell who is going to do the voting.

The result is that American political parties have weak central organizations and little central ideology, except by consensus. A party really cannot prevent a person who disagrees with the majority of positions of the party or actively works against the party's aims from claiming party membership, so long as the voters who choose to vote in the primary elections elect that person. Once in office, an elected official may change parties simply by declaring such intent.

At the federal level, each of the two major parties has a national committee (See, Democratic National Committee, Republican National Committee) that acts as the hub for much of the fund-raising and campaign activities, particularly in presidential campaigns. The exact composition of these committees is different for each party, but they are made up primarily of representatives from state parties, affiliated organizations, and other individuals important to the party. However, the national committees do not have the power to direct the activities of individual members of the party.

The map below shows the results of the 2012 Presidential Election in the United States, illustrating the strength of the two major parties varies by geographic region in the U.S., with Republicans stronger in the South, Midwest, and some Mountain states while Democrats are stronger along the coasts.

Sweden

[edit | edit source]Sweden has a multi-party system, with numerous parties in which no one party often has a chance of gaining power alone, and parties must work with each other to form coalition governments. A multi-party system is a system in which three or more political parties have the capacity to gain control of government separately or in coalition.

Unlike a single-party system (or a non-partisan democracy), it encourages the general constituency to form multiple distinct, officially recognized groups, generally called political parties. Each party competes for votes from the enfranchised constituents (those allowed to vote). A multi-party system is essential for representative democracies, because it prevents the leadership of a single party from setting policy without challenge.

If the government includes an elected Congress or Parliament the parties may share power according to Proportional Representation or the First-past-the-post system. In Proportional Representation, each party wins a number of seats proportional to the number of votes it receives. In first-past-the-post, the electorate is divided into a number of districts, each of which selects one person to fill one seat by a plurality of the vote. First-past-the-post is not conducive to a proliferation of parties, and naturally gravitates toward a two-party system, in which only two parties have a real chance of electing their candidates to office. This gravitation is known as Duverger's law. Proportional Representation, on the other hand, does not have this tendency, and allows multiple major parties to arise.

This difference is not without implications. A two-party system requires voters to align themselves in large blocs, sometimes so large that they cannot agree on any overarching principles. Along this line of thought, some theories argue that this allows centrists to gain control. On the other hand, if there are multiple major parties, each with less than a majority of the vote, the parties are forced to work together to form working governments. This also promotes a form of centrism.

The United States is an example of where there may be a multi-party system but that only two parties have ever formed government. Germany, India, France, and Israel are examples of nations that have used a multi-party system effectively in their democracies (though in each case there are two parties larger than all others, even though most of the time no party has a parliamentary majority by itself). In these nations, multiple political parties have often formed coalitions for the purpose of developing power blocs for governing.

The multi-party system of proportional representation has allowed a small third party, The Pirate Party, to come to prominence in Sweden, something that would be very unlikely in the United States. The Pirate Party strives to reform laws regarding copyright and patents. The agenda also includes support for a strengthening of the right to privacy, both on the Internet and in everyday life, and the transparency of state administration. The Party has intentionally chosen to be block independent on the traditional left-right scale to pursue their political agenda with all mainstream parties. The Pirate Party is the third largest party in Sweden in terms of membership. Its sudden popularity has given rise to parties with the same name and similar goals in Europe and worldwide.

Voting Patterns and Inequality

[edit | edit source]In any political system where voting is allowed, some people are more likely to vote than others (see this Wikipedia article on Voter turnout for more information on this). Additionally, some people are more likely to have access to political power than are others. It is in teasing out the stratification of political participation and political power that the sociological imagination is particularly useful.

Politics and Gender

[edit | edit source]While women are generally as likely to vote (or even more likely to vote; see figure below) in developed countries, women are underrepresented in political positions. Women make up a very small percentage of elected officials, both at local and national levels. In the U.S., for instance, in the 109th Congress (2005-2007) there were only 14 female Senators (out of 100) and 70 Congressional Representatives (out of 435). This is illustrated in the graph below:

In 2010 things had improved slightly; 17.2% of the House and 17% of the Senate were women, though a substantial imbalance remained between the two political parties.[3]

One of the factors that predicts how people vote is attitudes toward gender equality.[4] U.S. counties with sex segregated occupations are 11% more likely to vote Republican than counties that have mixed-sex occupations. McVeigh and Sobolewski (2007) argue that the white males in sex segregated counties are more likely to vote for conservative candidates because they feel their occupational security is threatened by women and racial minorities.

Politics and Age

[edit | edit source]Young people are much less likely to vote than are older people and are less likely to be politicians.[3] This is illustrated for young people in the U.S. in the graph below:

The lower voting rates of young people in the U.S. help explain why things like Medicare and Social Security in the U.S. are facing looming crises - the elderly will retain many of the benefits of these programs and are unwilling to allow them to be changed even though young people will be the ones to suffer the consequences of these crises. Older people are also more organized, through organizations like the AARP and are more likely to vote as a block on issues that affect them directly. As a result, older individuals in the U.S. have more power than younger people.

Politics and Race

[edit | edit source]Generally, racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to vote in elections and are also underrepresented in political positions, but these numbers are often influenced by ongoing attempts throughout American history to make voting harder (and at times impossible) for racial minorities. The graph below illustrates the disparate voting rates between racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. in the 2008 Presidential Election:

Racial and ethnic minorities are also less likely to hold political positions. If blacks were represented in proportion to their numbers in the U.S., there should be 12 Senators and 52 Members of the House. In 2009 there was 1 black Senator (Roland Burris) and 39 Members of the House. In 2010 the number in the House increased slightly to 41 (7.8%), but remained at just 1% of the Senate.[3]

Politics and Class

[edit | edit source]Another way that political power is stratified is through income and education. Wealthier and more educated people are more likely to vote, and voting times and locations in the United States generally favor middle-class and above occupational and educational schedules (see figures to the right). Additionally, wealthier and more educated people are more likely to hold political positions. A good illustration of this is the 2004 Presidential Election in the U.S. The candidates, John Kerry, and George W. Bush are both Yale University alumni. John Kerry is a lawyer and George W. Bush has an MBA from Harvard. Both are white, worth millions of dollars, and come from families that have been involved in politics.

Politics and Ideology

[edit | edit source]Recent research in the US suggests that there has been a growing bifurcation in political ideology. There is an increasing gap between individuals who espouse conservative ideology and those who advocate a more progressive ideology. This gap is the largest seen in at least the last twenty years.[5] One consequence of this bifurcation of ideology, combined with population shifts through migration, is population segregation based on ideology; some Americans are literally choosing where to live based on their perception of whether their political views align with those of their potential neighbors.[6] Another consequence is a shift in trust. People in the US have begun to trust information they receive from immediate family members, churches, close friends, and local newspapers more than they trust information coming from politicians, national news media, the internet, and co-workers.[7] A number of social networks and large corporations, whether or not they are aware of this research, appear to be taking advantage of this shift in trust by utilizing members of someone's social network to target advertising toward that individual.[8]

This bifurcation of political views in the US, when combined with election outcome expectations - which are heavily influenced by media - can lead to complications for democratic governments. Recent research suggests that individuals who believed their presidential candidate was going to win - largely because of a high consumption of biased media - reported greater distrust in government and democracy when their candidate did not win. In contrast, those who did not think their candidate was going to win did not exhibit the same decline in trust of democracy and government.[9] The growth of news media - particularly cable television channels - that cater to specific biases is, indirectly at least, eroding confidence in democracy.

Additional Reading

[edit | edit source]Campbell, John. 1993. “The State and Fiscal Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology. 19: 163-85. Gilbert, Jess and Carolyn Howe. 1991. “Beyond State vs. Society: Theories of the State and New Deal Agriculture Policies.” American Sociological Review 56:204-220. Goodwin, Jeff. 2001. No Other Way Out: States and Revolutionary Movements, 1945 – 1991. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Markoff, James. 1996. Waves of Democracy. New York: Routledge. Quadagno, Jill. 2004. ”Why the United States Has No National Health Insurance: Stakeholder Mobilization Against the Welfare State, 1945-1996.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 45:25-44 Brooks, Clem. 2000. "Civil Rights Liberalism and the Suppression of a Republican Political Realignment in the United States, 1972 to 1996." American Sociological Review 65:483-505. Brooks, Clem. 2004. "A Great Divide? Religion and Political Change in U.S. National Elections, 1972-2000." The Sociological Quarterly 45:421-50. Brooks, Clem and Jeff Manza. 1997. "Social Cleavages and Political Alignments: U.S. Presidential Elections, 1960 to 1992." American Sociological Review 62:937-46. Campbell, John L. 2002. “Ideas, Politics, and Public Policy.” Annual Review of Sociology 28:21-38. Burstein, Paul and April Linton. 2002. “The Impact of Political Parties, Interest Groups, and Social Movement Organizations on Public Policy: Some Recent Evidence and Theoretical Concerns.” Social Forces 81:380-408. Burstein, Paul and April Linton. 2002. “The Impact of Political Parties, Interest Groups, and Social Movement Organizations on Public Policy: Some Recent Evidence and Theoretical Concerns.” Social Forces 81:380-408. Jacobs, David and Daniel Tope. 2007. “The Politics of Resentment in the Post Civil-Rights Era: Minority Threat, Homicide, and Ideological Voting in Congress.” American Journal of Sociology 112: 1458-1494. Skrentny, John. 2002. The Minority Rights Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard.

Discussion Questions

[edit | edit source]- While there are many more types of government, based on what you've just read, do you think there is a type that is better than the others? If so, why do you think that?

- Why are there just two dominant political parties in the US? What are the consequences of this?

- Why are young people less likely to vote than are elderly people? What are the consequences of this?

- How could you get more young people to vote?

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ R. Alan Dahl, I. Shapiro, J. A. Cheibub, The Democracy Sourcebook, MIT Press 2003, ISBN 0262541475

- ↑ G. F. Gaus, C. Kukathas, Handbook of Political Theory, SAGE, 2004, p. 143-145, ISBN 0761967877

- ↑ a b c Roberts, Sam. 2010. “Congress and Country: Behold the Differences.” The New York Times, February 10 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/10/us/politics/10congress.html (Accessed February 10, 2010).

- ↑ McVeigh, Rory, and Juliana M. Sobolewski. 2007. “Red Counties, Blue Counties, and Occupational Segregation by Sex and Race.” American Journal of Sociology 113:446-506.

- ↑ Pew Research Center. 2014. Political Polarization in the American Public: How Increasing Ideological Uniformity and Partisan Antipathy Affect Politics, Compromise and Everyday Life. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved (http://www.people-press.org/files/2014/06/6-12-2014-Political-Polarization-Release.pdf).

- ↑ Gimpel, James G. and Iris S. Hui. 2015. Seeking politically compatible neighbors? The role of neighborhood partisan composition in residential sorting. Political Geography. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.11.003

- ↑ Smith, Jordan W. 2013. “Information Networks in Amenity Transition Communities: A Comparative Case Study.” Human Ecology 41(6):885–903.

- ↑ Sengupta, Somini. 2012. “So Much for Sharing His ‘Like.’” The New York Times, May 31. Retrieved June 20, 2014 (http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/01/technology/so-much-for-sharing-his-like.html).

- ↑ Hollander, Barry A. 2014. “The Surprised Loser The Role of Electoral Expectations and News Media Exposure in Satisfaction with Democracy.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 1077699014543380.