Introduction to Library and Information Science/Print version

| This is the print version of Introduction to Library and Information Science You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/Contextualizing Libraries: Their History and Place in the Wider Information Infrastructure

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/Ethics and Values in the Information Professions

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/Information Policy

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/Information Organization

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/Information Seeking

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/Re-contextualizing Libraries: Considering Libraries within Their Communities

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/Technology and Libraries: Impacts and Implications

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/Transcending Boundaries: Global Issues and Trends

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/Learning More: Free LIS Resources

- Introduction to Library and Information Science/List of Contributors

Contextualizing Libraries: Their History and Place in the Wider Information Infrastructure

[edit | edit source]

This chapter will draw on two important fields to define roles and contexts for librarianship and other information work. First, we will explore the many diverse roles libraries have played throughout history, exploring the different motivations for libraries and services library workers have provided towards these motivations. We will then look at how different individuals and fields conceive of information in today's world, and how these conceptions inform their practice. We will conclude by drawing on historical LIS practice and lessons learned from related disciplines to establish roles and a scope for contemporary LIS practice and scholarship.

After reading this chapter, a student should be able to articulate:

- what a library is

- the value of critically examining library history to inform current library practice

- the missions and practices of libraries in ancient and medieval European libraries

- the contributions of pre-modern East Asian, Middle Eastern, and African libraries to contemporary library practice

- exclusionary practices and policies in 19th- and 20th-century libraries in the United States

- the concepts of ahistoricism and tunnel vision

- definitions of information from several different fields, and how they inform LIS practice

- how the following fields relate to LIS

- Computer science

- Education

- Information theory

- Social work

Defining libraries

[edit | edit source]| This page or section is an undeveloped draft or outline. You can help to develop the work, or you can ask for assistance in the project room. |

A library can be defined as a major department concerned with the collection, organization, dissemination of recorded information, facts or readable material for the purpose of teaching, learning and research.

Libraries of the past

[edit | edit source]This section will introduce characteristics and purposes of libraries throughout time, and then introduce some critical issues and methods of library history.

A brief history of libraries

[edit | edit source]Early libraries (2600 BC – 800 BC)

[edit | edit source]

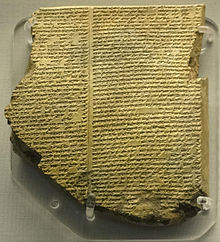

The first libraries consisted of archives of the earliest form of writing - the clay tablets in cuneiform script discovered in temple rooms in Sumer[1].

The earliest discovered private archives were kept at Ugarit (in present-day Syria); besides correspondence and inventories, texts of myths may have been standardized practice-texts for teaching new scribes. There is also evidence of libraries at Nippur about 1900 BC and those at Nineveh about 700 BC showing a library classification system.[2]

Over 30,000 clay tablets from the Library of Ashurbanipal have been discovered at Nineveh,[3] providing modern scholars with an amazing wealth of Mesopotamian literary, religious and administrative work. Among the findings were the Enuma Elish, also known as the Epic of Creation,[4] which depicts a traditional Babylonian view of creation, the Epic of Gilgamesh,[5] a large selection of "omen texts" including Enuma Anu Enlil which "contained omens dealing with the moon, its visibility, eclipses, and conjunction with planets and fixed stars, the sun, its corona, spots, and eclipses, the weather, namely lightning, thunder, and clouds, and the planets and their visibility, appearance, and stations",[6] and astronomic/astrological texts, as well as standard lists used by scribes and scholars such as word lists, bilingual vocabularies, lists of signs and synonyms, and lists of medical diagnoses.

Philosopher Laozi was keeper of books in the earliest library in China, which belonged to the Imperial Zhou dynasty.[7] Also, evidence of catalogues found in some destroyed ancient libraries illustrates the presence of librarians.[7]

Classical period (800 BC – 500 AD)

[edit | edit source]

The Library of Alexandria

[edit | edit source]The Library of Alexandria, in Egypt, was the largest and most significant great library of the ancient world. It flourished under the patronage of the Ptolemaic dynasty and functioned as a major center of scholarship from its construction in the 3rd century BC until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. The library was conceived and opened either during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter (323–283 BC) or during the reign of his son Ptolemy II (283–246 BC).[8] An early organization system was in effect at Alexandria.[8]

Much of what we know about the Alexandrian library is not based on verifiable fact, but rather a collection of stories, many of which we should forego according to Jochum’s research. There are no physical remnants of the library left, only written allusions from classical writers, but he believes that the great library did not exist merely as single building. The Alexandrian library claimed to have contained every book on every subject in every language. The methods for acquiring these books varied. One reported method was to employ traders to buy books wherever they could be found. Another claimed that books were confiscated from ships in the Alexandrian harbor, then copied for the library and returned to their owners. Catalogs were made of the collection’s books, including the metadata on the original owners and where the copy was copied or written.

Today, the thought of a library containing every book on every subject in every known language is impossible, especially as technology advances. As long ago as 1976, having the information available digitally was proposed as the way to emulate the ideal of the Alexandrian library. The economies offered by digitalization can get us access to the type of knowledge sought by the Greeks. Jochum offers that the Alexandrian may not have existed as the ultimate facility. Once we can weed out the lore from fact, we can then begin to move forward with the library as a learning center instead of a just physical repository for books.[9]

Other Classical libraries

[edit | edit source]Private or personal libraries made up of written books (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) appeared in classical Greece in the 5th century BC. The celebrated book collectors of Hellenistic Antiquity were listed in the late 2nd century in Deipnosophistae. All these libraries were Greek; the cultivated Hellenized diners in Deipnosophistae pass over the libraries of Rome in silence. By the time of Augustus there were public libraries near the forums of Rome: there were libraries in the Porticus Octaviae near the Theatre of Marcellus, in the temple of Apollo Palatinus, and in the Bibliotheca Ulpiana in the Forum of Trajan. The state archives were kept in a structure on the slope between the Roman Forum and the Capitoline Hill.

Private libraries appeared during the late republic: Seneca the Younger inveighed against libraries fitted out for show by illiterate owners who scarcely read their titles in the course of a lifetime, but displayed the scrolls in bookcases (armaria) of citrus wood inlaid with ivory that ran right to the ceiling: "by now, like bathrooms and hot water, a library is got up as standard equipment for a fine house (domus).[10] Libraries were amenities suited to a villa, such as Cicero's at Tusculum, Maecenas's several villas, or Pliny the Younger's, all described in surviving letters. At the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, apparently the villa of Caesar's father-in-law, the Greek library has been partly preserved in volcanic ash; archaeologists speculate that a Latin library, kept separate from the Greek one, may await discovery at the site.

In the West, the first public libraries were established under the Roman Empire as each succeeding emperor strove to open one or many which outshone that of his predecessor. Unlike the Greek libraries, readers had direct access to the scrolls, which were kept on shelves built into the walls of a large room. Reading or copying was normally done in the room itself. The surviving records give only a few instances of lending features. As a rule, Roman public libraries were bilingual: they had a Latin room and a Greek room. Most of the large Roman baths were also cultural centres, built from the start with a library, a two room arrangement with one room for Greek and one for Latin texts.

Libraries were filled with parchment scrolls as at Library of Pergamum and on papyrus scrolls as at Alexandria: the export of prepared writing materials was a staple of commerce. There were a few institutional or royal libraries which were open to an educated public (such as the Serapeum collection of the Library of Alexandria, once the largest Great library in the ancient world),[8] but on the whole collections were private. In those rare cases where it was possible for a scholar to consult library books there seems to have been no direct access to the stacks. In all recorded cases the books were kept in a relatively small room where the staff went to get them for the readers, who had to consult them in an adjoining hall or covered walkway.

Han Chinese scholar Liu Xiang established the first library classification system during the Han Dynasty,[11] and the first book notation system. At this time the library catalogue was written on scrolls of fine silk and stored in silk bags.

Middle Ages (501 AD – 1400 AD)

[edit | edit source]In the 6th century, at the very close of the Classical period, the great libraries of the Mediterranean world remained those of Constantinople and Alexandria.

Cassiodorus, minister to Theodoric, established a monastery at Vivarium in the heel of Italy with a library where he attempted to bring Greek learning to Latin readers and preserve texts both sacred and secular for future generations. As its unofficial librarian, Cassiodorus not only collected as many manuscripts as he could, he also wrote treatises aimed at instructing his monks in the proper uses of reading and methods for copying texts accurately. In the end, however, the library at Vivarium was dispersed and lost within a century.

Through Origen and especially the scholarly presbyter Pamphilus of Caesarea, an avid collector of books of Scripture, the theological school of Caesarea won a reputation for having the most extensive ecclesiastical library of the time, containing more than 30,000 manuscripts: Gregory Nazianzus, Basil the Great, Jerome and others came and studied there.

By the 8th century first Iranians and then Arabs had imported the craft of papermaking from China, with a paper mill already at work in Baghdad in 794. By the 9th century public libraries started to appear in many Islamic cities. They were called "halls of Science" or dar al-'ilm. They were each endowed by Islamic sects with the purpose of representing their tenets as well as promoting the dissemination of secular knowledge. The 9th century Abbasid Caliph al-Mutawakkil of Iraq, ordered the construction of a "zawiyat qurra" – an enclosure for readers which was "lavishly furnished and equipped".

In Shiraz, Adhud al-Daula (d. 983) set up a library, described by the medieval historian al-Muqaddasi as "a complex of buildings surrounded by gardens with lakes and waterways. The buildings were topped with domes, and comprised an upper and a lower story with a total, according to the chief official, of 360 rooms.... In each department, catalogs were placed on a shelf... the rooms were furnished with carpets".[12]

The libraries often employed translators and copyists in large numbers, in order to render into Arabic the bulk of the available Persian, Greek, Roman and Sanskrit non-fiction and the classics of literature.

This flowering of Islamic learning ceased centuries later, after many of these libraries were destroyed by Mongol invasions. Others were victim of wars and religious strife in the Islamic world. However, a few examples of these medieval libraries, such as the libraries of Chinguetti in West Africa, remain intact and relatively unchanged. Another ancient library from this period which is still operational and expanding is the Central Library of Astan Quds Razavi in the Iranian city of Mashhad, which has been operating for more than six centuries.

The contents of these Islamic libraries were copied by Christian monks in Muslim/Christian border areas, particularly Spain and Sicily. From there they eventually made their way into other parts of Christian Europe. These copies joined works that had been preserved directly by Christian monks from Greek and Roman originals, as well as copies Western Christian monks made of Byzantine works.

Buddhist scriptures, educational materials, and histories were stored in libraries in pre-modern Southeast Asia. In Burma, a royal library called the Pitaka Taik was legendarily founded by King Anawrahta;[13] in the 18th century, British envoy Michael Symes, upon visiting this library, wrote that "it is not improbable that his Birman majesty may possess a more numerous library than any potentate, from the banks of the Danube to the borders of China". In Thailand libraries called ho trai were built throughout the country, usually on stilts above a pond to prevent bugs from eating at the books.

In the Early Middle Ages, monastery libraries developed, such as the important one at the Abbey of Montecassino. Books were usually chained to the shelves, and these chained libraries reflected the fact that manuscripts, created via the labour-intensive process of hand copying, were valuable possessions.[14] Despite this protectiveness, many libraries loaned books if provided with security deposits (usually money or a book of equal value). Lending was a means by which books could be copied and spread. In 1212 the council of Paris condemned those monasteries that still forbade loaning books, reminding them that lending is "one of the chief works of mercy."[15] The early libraries located in monastic cloisters and associated with scriptoria were collections of lecterns with books chained to them. Shelves built above and between back-to-back lecterns were the beginning of bookpresses. The chain was attached at the fore-edge of a book rather than to its spine. Book presses came to be arranged in carrels (perpendicular to the walls and therefore to the windows) in order to maximize lighting, with low bookcases in front of the windows. This "stall system" (fixed bookcases perpendicular to exterior walls pierced by closely spaced windows) was characteristic of English institutional libraries. In European libraries, bookcases were arranged parallel to and against the walls. This "wall system" was first introduced on a large scale in Spain's El Escorial.

Renaissance

[edit | edit source]

In Rome, the papal collections were brought together by Pope Nicholas V, in separate Greek and Latin libraries, and housed by Pope Sixtus IV, who consigned the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana to the care of his librarian, the humanist Bartolomeo Platina in February 1475.[16]

The 16th and 17th centuries saw other privately endowed libraries assembled in Rome: the Vallicelliana, formed from the books of Saint Filippo Neri, with other distinguished libraries such as that of Cesare Baronio, the Biblioteca Angelica founded by the Augustinian Angelo Rocca, which was the only truly public library in Counter-Reformation Rome; the Biblioteca Alessandrina with which Pope Alexander VII endowed the University of Rome; the Biblioteca Casanatense of the Cardinal Girolamo Casanate; and finally the Biblioteca Corsiniana founded by the bibliophile Clement XII Corsini and his nephew Cardinal Neri Corsini, still housed in Palazzo Corsini in via della Lungara.

The Republic of Venice patronized the foundation of the Biblioteca Marciana, based on the library of Cardinal Basilios Bessarion. In Milan, Cardinal Federico Borromeo founded the Biblioteca Ambrosiana. This trend soon spread outside of Italy, for example Louis III, Elector Palatine founded the Bibliotheca Palatina of Heidelberg. These libraries don't have so many volumes as the modern libraries. However, they keep many valuable manuscripts of Greek, Latin and Biblical works.

Tianyi Chamber, founded in 1561 by Fan Qin during the Ming Dynasty, is the oldest surviving library in China. In its heyday it boasted a collection of 70,000 volumes of antique books.

17th and 18th centuries

[edit | edit source]

During the 17th and 18th centuries, some of the more important European libraries were founded, such as the Bodleian Library at Oxford, the British Museum Library in London, the Mazarine Library and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris, the Austrian National Library in Vienna, the National Central Library in Florence, the Prussian State Library in Berlin, the Załuski Library in Warsaw and the M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin State Public Library of St Petersburg.[17]

The 18th century is when we see the beginning of the modern public library. In France, the French Revolution saw the confiscation in 1789 of church libraries and rich nobles' private libraries, and their collections became state property. The confiscated stock became part of a new national library – the Bibliothèque Nationale. Two famous librarians, Hubert-Pascal Ameilhon and Joseph Van Praet, selected and identified over 300,000 books and manuscripts that became the property of the people in the Bibliothèque Nationale.[18] During the French Revolution, librarians were solely responsible for the bibliographic planning of the nation. Out of this came the implementation of the concept of library service – the democratic extension of library services to the general public regardless of wealth or education.[18]

19th century

[edit | edit source]_The Industrial Revolution_

20th century

[edit | edit source]After the World Wars, Cold Wars and the introduction of Technology in libraries Stephen Cresswell reviews literature concerning libraries, the civil rights movement and the end of segregation in Southern libraries. The ALA did not actively support library integration. As Rubin notes, until the 1960s, the ALA considered itself an association representing only its constituency of librarians (Rubin, 294). Efforts by the ALA included:

- The 1936 decision to boycott convention cities where hotels and restaurants were segregated.

- In the late 1950s and 1960s ALA denied membership to segregated state library associations and ruled a state could have only one state association.

- The 1961 amendment to the Library Bill of Rights stated that the right of an individual to the use of a library should not be abridged because of his race, religion, national origins or political views.

- In 1962 the organization undertook an “Access Study” to evaluate freedom of access throughout the country.

The study revealed more segregation and inequities in libraries in northern cities than in the South. Northern libraries were sometimes the focus of destructive demonstrations. In the South they were often the first focus of civil rights demonstrations rather than schools, because they evoked sympathy for the individual’s right to learn, rather than the more emotional reactions to integrating public schools.

Issues in library history

[edit | edit source]Ahistoricism

[edit | edit source]Lancaster, F.W. (1978). Toward paperless information systems.

Harris and Hannah (1992). Why do we study the history of libraries?

Black, Alastair. "Information and Modernity: The History of Information and the Eclipse of Library History." Library History 14 (May 1998): 39-45.

Gender

[edit | edit source]Garrison, writing in 1972, highlights a problem of the public image of librarianship: it has not attained the status of the more scientific professions such as doctor, sociologist, etc. One possible reason, the one central to this article, is the entrée of women into the field during the Victorian era. Garrison examines three tenets that make a profession: service, knowledge, and autonomy. Librarians, as professionals, serve their clients (community or society); female librarians, on the other hand, were to be almost subservient. The knowledge required of a librarian, considered highly educated for a woman at the time, lacked the standardized training for a doctor. Libraries were governed by boards populated by men, not female librarians, who made key decisions. Garrison concludes that until library science comes to terms with women’s early employment in libraries and the way it has shaped the current assumptions, it will never attain the rank of other professions. Garrison provides a lively essay on the history of female librarians and its manifestations today. Her perspective, however, is colored by feminism’s second wave in the 1970s.

Perhaps the public image of librarianship today should not focus so much on doctors and sociologists, but the more technology-based professions under the information science umbrella. For instance, librarians are not seen as the driving force behind innovation like software engineers and others in the IT field. Would an analysis of women in the early stages of librarianship give insight into why some have trouble with the information science moniker?[20]

Even though the profession of a librarian is considered "women's work" there are men who have chosen this profession. However, they usually hold positions of upper management and other higher paying areas. What exactly is "women's work" within the library environment? Suzanne Hildenbrand argues that cataloging and services for children and youth are most often seen in this way. There are statistics that show these two positions are the lowest paid and are not held in high esteem within the library workplace. The author raises a great point that what needs to be focused on is not the movement of women into management positions and other high paying positions but one that focuses on the equality of salaries and conditions within the most female concentrated specialties up to the standard of the profession [21]

Inclusions and exclusions

[edit | edit source]Before 1960, there were no public library services for ethnic minorities. During the 1960’s and 1970’s, many attempts to design and develop library services for ethnic groups were put into motion. The cultural programs that flourished were programs that had adequate federal funding for services and experimentation. Other factors that contributed to successful programs:

- Recruitment of appropriate staff to identify information needs and promote library programs

- Involvement by the community in planning and developing services

- Developed mechanisms that enable the community to identify its own needs

- Link the needs to the expertise of librarians

Ethnic library services have been dropping gradually since 1981; and libraries are still failing to include: books, periodicals, films, recording, and archives that relate to various minority groups. Rethinking ideas to meet different needs is required when there are demographic changes, and libraries should take proper steps to appeal to everyone [22].

It is important to have a diverse staff, particularly when a diverse clientele is involved. There has been a decrease in college enrollment amongst minorities; and in 1991-1992, only 8.5% of the Library and Information Science graduates were minorities. There are five tasks administrators and librarians should implement, so the number of graduates increase in the library program:

- Cooperative efforts to hire minority graduates

- Additional monetary incentives ? scholarships, tuition waivers, and housing

- Recruitment activities aimed at students as early as the junior high school

- Recruitment of nontraditional students from military or community colleges

- Development of an academic and social environment on campus conducive to success

In 1993, a few efforts have been made to recruit minorities, but none had been particularly successful. In order to make recruitment more successful, it must be considered a priority [23]

Salvador Guerena and Edward Erazo have three recommendations for the future of Latinos and libraries:

- Increase recruitment, retention, and mentoring of bilingual/ bicultural Latino professional personnel.

- Include members of the Latino community in the process of planning library services for the community.

- Foster networking among libraries providing service to the Latino community.

Hispanics represent the fastest growing demographic group in the United States, but Latino librarianship has remained constant at 1.8% of librarians. Shortages of bilingual librarians will continue to increase. Foreign language proficiency is not required of library schools so graduates are not prepared to serve the needs of the Latino community. REFORMA, LSTA, and ALA have been advocates for training, improving technology and curriculum in response to changing multicultural, multiethnic and multilingual society. The article is informative yet pessimistic. It recognizes the technological divide in the Hispanic community and the need for education and availability of computers in libraries. The affordability of computers has not increased ownership of computers in their homes. In West Chicago Middle School, many Latino students use the computers in the classroom to complete their assignments. For many of these students, high school will be the end of their formal education. At the Olcott library, the greatest demand for Spanish titles comes from Miami and Los Angeles not locally. A telling observation of the article is that Hispanics do not feel welcome in libraries because Hispanics feel libraries are Anglo American institutions run by and for Anglo Americans.[24]

Tunnel vision

[edit | edit source]Wayne Weigand says that "a constant re-examination of our past [...] can show the parameters of tunnel vision and reveal many of the blind spots". Librarians often act as "stewards" of the past, which may mean perpetuating many of the past's close-minded views.[25]

Library collections, like the steward-librarians Weigand mentions are "products of our pasts". Unless we have the luxury of throwing out our entire collection and starting anew, we are stuck with including the tunnel vision of the past in our libraries.

Libraries in the information age

[edit | edit source]Defining information

[edit | edit source]There are many ways of defining and conceptualizing information. Definitions can focus on the technical aspects of information, or the societal aspects.

Technical aspects

[edit | edit source]Information as a sequence of symbols

[edit | edit source]In its most restricted technical sense, is a sequence of symbols that can be interpreted as a message. Information can be recorded as signs, or transmitted as signals.

Societal aspects

[edit | edit source]Information as a right

[edit | edit source]In an article written for the Bowker Annual in 1987, Kenneth Dowlin discusses the need for the library profession to ensure that access to information remains available, as a basic human right, to everyone in an age where we are moving from an industrial to an information society. He argues that the mission of libraries should be to develop minimum standards of access and “promote the compatibility of information systems”. Dowlin gives a brief discussion of why information must be considered a human right, and identifies several barriers to this, namely

- Legislative barriers

- Competitive barriers

- Technological barriers

- Perceptual barriers

- Economic barriers

He then proposes some strategies to reduce these barriers and defines the role the library profession should play in implementing them.

I believe that he is correct in his assessment of the barriers that exist, and that libraries should play a role in ensuring access for all to information, but disagree with most of his proposed solutions, which in my mind are based on false assumptions, which time has borne out. He asks the library profession to implement solutions they are not equipped to deal with and have no control over. The library profession has no way to set standards of technology to ensure access for all. Letting the private sector derive solutions to these barriers, has proven the best way to overcome the barriers he has identified. Although Dowlin’s fundamental statement is correct, it is questionable whether his solutions are practical or achievable in the real world.[26]

Information as a commodity

[edit | edit source]Quantifying information

[edit | edit source]There is a plethora of ways to think about information, and those involved in information and knowledge work have a number widely divergent agendas. This can make evaluation of information services very difficult. Some groups attempt to make such evaluation mathematical and scientific, while others rely on tools from the social sciences, such as surveys and studies. The mathematical and scientific groups often try to measure a service's value using calculations and monetary values.

While the United Kingdom conducted a survey that had people evaluate how much service they received and how it contributed to their productivity. The article wasn't necessarily aimed at just the business world. The author did a great job at relating this to the library field by talking about the amount of knowledge you poses and how useful that makes you. It talked about the more knowledgeable you are, the more productive you will be, and the more assistance you will be able to provide. From our discussion last week in class about what makes a good librarian this was one of the major things that we all thought made a good librarian. I feel the more informed and versatile you are in all different aspects, the more you will have to draw upon and offer. All of that contributes to your ability to be more productive for the patrons that you assist.[27]

Defining knowledge

[edit | edit source]Knowledge is a general understanding or familiarity with a subject, place, situation, etc. Knowledge can be acquired through experience or education.

Information needs

[edit | edit source]An information need is a gap in a person's knowledge. When a person identifies such a gap, it may be expressed as a question or a search query.

Education

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Casson, Lionel (11 Aug 2002). Libraries in the Ancient World. Yale University Press. p. 3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ The American International Encyclopedia, New York: J. J. Little & Ives, 1954; Volume IX

- ↑ Britishmuseum.org "Assurbanipal Library Phase 1", British Museum One

- ↑ "Epic of Creation", in Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia. Oxford, 1989; pp. 233-81

- ↑ "Epic of Gilgamesh", in Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia. Oxford, 1989; pp. 50–135

- ↑ Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–323 BC. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2007: pg. 263

- ↑ a b Mukherjee, A. K. Librarianship: Its Philosophy and History. Asia Publishing House (1966) p. 86

- ↑ a b c Phillips, Heather A., "The Great Library of Alexandria?". Library Philosophy and Practice, August 2010

- ↑ Jochum, Uwe. “The Alexandrian Library and Its Aftermath.” Library History 15 (May 1999): 5-12.

- ↑ Seneca, De tranquillitate animi ix.4–7.

- ↑ Zurndorfer, Harriet Thelma (1995). China bibliography: a research guide ... – Google Books. books.google.com.au. ISBN 978-90-04-10278-1.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Goeje, M. J. de, ed (1906). "Al-Muqaddasi: Ahsan al-Taqasim" (in Arabic). Bibliotheca geographorum Arabicorum. III. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 449.

- ↑ International dictionary of library histories, 29

- ↑ Streeter, Burnett Hillman (10 Mar 2011). The Chained Library. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ Geo. Haven Putnam (1962). Books and Their Makers in the Middle Ages. Hillary.

- ↑ This section on Roman Renaissance libraries follows Kenneth M. Setton, "From Medieval to Modern Library" Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 104.4, Dedication of the APS Library Hall, Autumn General Meeting, November, 1959 (August 1960:371–390) p. 372 ff.

- ↑ Stockwell, Foster (2000). A History of Information and Storage Retrieval. ISBN 0-7864-0840-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ↑ a b Mukherjee, A. K. (1966) Librarianship: its Philosophy and History. Asia Publishing House; p. 112

- ↑ Cresswell, Stephen. “The Last Days of Jim Crow in Southern Libraries.” Libraries and Culture 31 (summer/fall 1996): 557-573.

- ↑ Garrison, Dee. “The Tender Technicians: The Feminization of Public Librarianship, 1876-1905.” Journal of Social History 6 (winter 1972-1973): 131-156.

- ↑ Hildenbrand, Suzanne. "'Women's Work' within Librarianship." Library Journal 114 (September 1, 1989): 153-155.

- ↑ Trujillo, Roberto G., and Yolanda J. Cuesta, 1989. Service to Diverse Populations. ALA Yearbook of Library and Information Science. Vol. 14: 7-11.

- ↑ McCook, Kathleen, and Geist, Paula, 1993. Diversity Deferred: Where are the Minority Librarians? Library Journal. 118: 23-26.

- ↑ Guerena, Salvador and Edward Erazo. "Latinos and Librarianship." Library Trends 49 (2000) : 138-181.

- ↑ Wayne Wiegand, Tunnel Vision and Blind Spots: What the Past Tells Us about the present; reflections on the twentieth-century history of American librarianship (Library Quarterly, 69:1, Jan. 1999)

- ↑ Dowlin, Kenneth E. “Access to Information: A Human Right?” Bowker Annual 32 (1987): 64-68.

- ↑ Koenig, Michael E. D. “Information Services and Downstream Productivity.” Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 25 (1990): 55 – 86.

Ethics and Values in the Information Professions

[edit | edit source]

After reading this chapter, students should be able to articulate:

- The importance of defining a profession's values

- The difference between professional, general, personal, and rival values

- Ranganathan's Five Laws of Library Science

- ALA's Library Bill of Rights

- ALA's Code of Ethics

- A point of conflict between two different sets of value

- Their personal values

- How their personal and professional values will inform their LIS practice

The Values of librarianship

[edit | edit source]Values are essential to the success and future of librarianship: they highlight what is "important and worthy in the long run," and help to define our profession. In a literature review on professional values in LIS, Lee Finks argues that these values fall into four categories:

- Professional values are inherent in librarianship and include recognizing the importance of service and stewardship; maintaining philosophical values that reflect wisdom, truth, and neutrality; preserving democratic values; and being passionate about reading and books.

- General values are "commonly shared by normal, healthy people, whatever their field." Librarians' work, social, and satisfaction values express a commitment to lifelong learning, the importance of tolerance and cooperation, and the need to feel accepted.

- Personal values specifically belong to library workers and include humanistic, idealistic, conservative, and aesthetic values.

- Rival values threaten the mission of libraries with bureaucratic, anti-intellectual, and nihilistic ideas. Librarians must have faith in the profession's ability to do good. [1]

This section will mainly discuss professional values, but we will touch on several general, personal, and even rival values throughout the course of this book.

Defining professional values

[edit | edit source]In 1999, the ALA formed a task force to "to clarify the core values (credo) of the profession". This task force believed "that without common values, we are not a profession," and proposed the following definition of common goals for our field:

- Connection of people to ideas

- Assurance of free and open access to recorded knowledge, information and creative works

- Commitment to literacy and learning

- Respect for the individuality and the diversity of all peoples

- Freedom for all people to form, to hold, and to express their own beliefs

- Preservation of the human record

- Excellence in professional service to our communities

- Formation of partnerships to advance these values [2]

Despite the work of this task force, the ALA did not adopt a Core Value Statement until June 2004. This statement represented a compromise between the task force and its critics, and took its 11 core values from ALA policies that were already in effect. While the task force's document positioned these values in relation to our profession (for example, our profession must provide "assurance" that access to recorded knowledge is free and open), the official ALA policy simply lists the values. The ALA's wording also leaves its list open to other values as well, and lists these as examples of core values:

- Access

- Confidentiality/privacy

- Democracy

- Diversity

- Education and lifelong learning

- Intellectual freedom

- Preservation

- The Public good

- Professionalism

- Service

- Social responsibility [3]

Ranganathan's five laws

[edit | edit source]Establishing a core set of values is not the only way to define and provide direction for a field. Many of the natural sciences are based not on values, but on scientific laws. This led mathematician and librarian S.R. Ranganathan to propose Five laws of library science in 1931. Ranganathan envisioned these laws as a set of fundamental laws, analogous to the scientific laws that serve as fundamental principles for natural and some social sciences. Ranganathan's original laws were:

- Books are for use.

- Every reader [their] book.

- Every book its reader.

- Save the time of the reader.

- A library is a growing organism. [4]

Michael Gorman respectfully adjusted Ranganathan's laws to better fit the future needs and practices of libraries. Gorman's revised laws are:

- Libraries serve humanity- They should serve the individual, community and society to a higher quality. When making decisions, librarians should consider how the change will better serve humanity.

- Respect all forms by which knowledge is communicated- If there is a new means of communication of knowledge, and it is a better carrier, utilize it.

- Use technology intelligently to enhance service- Technology needs to be integrated so that it is used intelligently in a cost-effective and beneficial way.

- Protect free access to knowledge- The library is central to freedom. It needs to preserve all records so none are lost, and should be transmitted to all.

- Honor the past and create the future- Libraries need to combine the past and future in a rational manner. Not clinging to the past but looking forward for the better. [5]

Professional Ethics

[edit | edit source]Once we have defined goals for our profession, we need to make sure that we meet these goals in ethical ways. Library and Information workers are expected to follow certain ethical standards, typically codified in documents called Codes of Ethics. These codes offer a basis for making ethical decisions and applying ethical solutions to problems in LIS.

In the United States, professional librarian ethics are codified in the ALA's Code of Ethics, which are discussed below. However, there are other codes of ethics that are important to the LIS community, which are discussed later in this chapter.

The ALA's Code of Ethics

[edit | edit source]Highest level of service to all users

[edit | edit source]| “ | We provide the highest level of service to all library users through appropriate and usefully organized resources; equitable service policies; equitable access; and accurate, unbiased, and courteous responses to all requests. | ” |

Intellectual freedom

[edit | edit source]| “ | We uphold the principles of intellectual freedom and resist all efforts to censor library resources. | ” |

Intellectual freedom is a major area of conflict within libraries. Intellectual freedom is a goal that most library workers can agree on in theory, but situations in everyday library work can complicate this seemingly simple rule.

Challenged materials.

Another issue, brought up by John Swan, is how libraries should represent points of view that are completely wrong. Swan asks if "Truth" should play the pivotal role as the raison d’etre of libraries, or if libraries serve another cause entirely? His topics for discussion include:

- Are libraries committed to "Truth" for legal purposes?

- The role of "Truth", "Untruth" and Libraries.

- "Truth" is necessary for the law, but "Untruths" are a necessary function of libraries.

- Intellectual freedom, not "Truth" should be the driving force for libraries.

- Libraries have a duty to present Untruths".

His conclusions are that libraries exist, by their very nature, as forums for ideas. According to Swan, both "Truth" and "Untruth" are necessary in providing information to the public in these forums. The role of libraries is access to both, and in fact one cannot exist without the other. Swan makes distinctions about the differing roles of the legal system, third party groups, libraries and the role that censorship plays from pressure groups. These distinctions are as real and pertinent today as they were 20 years ago, in fact more so, as there is more "conflicting" information available to the public today due to advances in technology (internet, blogs, etc.).[6]

Privacy and confidentiality

[edit | edit source]| “ | We protect each library user's right to privacy and confidentiality with respect to information sought or received and resources consulted, borrowed, acquired or transmitted. | ” |

Intellectual property rights

[edit | edit source]| “ | We recognize and respect intellectual property rights | ” |

Intellectual property rights are a difficult issue. While most of the rest of the ALA's Code of Ethics talks about how libraries should provide unrestricted access to information, copyright and other intellectual property rights can sometimes provide restrictions on this flow of information. Libraries have taken an active interest in open licensing, free software, and new publication and distribution models that respect the rights of information creators while allowing more widespread access to ideas.

David Dorman asserts that the Open Source Software movement is akin to librarians' views of information. That is, information is public property and as such anyone should have access to it. OSS furthers this by emphasizing the software that holds the information: if control of the software is eliminated, the information itself is more free and accessible. Thus, the Information Control Wars is the battle between those who believe technology should promote free access to information, and those who believe technology should control it for their economic and political gain. Dorman presents a thoughtful treatise on the philosophical, democratic, and tangible merits of OSS. His analysis sheds light on the legal implications of patent and copyright legislation of which the casual supporter of OSS may not be aware.

The discussion of OSS in context with information belonging to all brings to mind SCO Group’s many lawsuits against companies who allegedly copied source code that, OSS advocates argue, was free to begin with. Little SCO taking on the big, bad corporation of IBM, for example, seems on the surface to underscore democracy. But SCO’s claims run against the intent of OSS, and their attempts to extract monies seem ill-founded at best. The question arises nonetheless: how does one determine when intellectual property has been violated in OSS? If there is a violation in the OSS world, what implications does that have for its future? What are the implications for those who support free information and access?[7]

Respecting fellow library workers

[edit | edit source]| “ | We treat co-workers and other colleagues with respect, fairness and good faith, and advocate conditions of employment that safeguard the rights and welfare of all employees of our institutions. | ” |

Non-advancement of private interests

[edit | edit source]| “ | We do not advance private interests at the expense of library users, colleagues, or our employing institutions. | ” |

Distinguishing between personal convictions and professional duties

[edit | edit source]| “ | We distinguish between our personal convictions and professional duties and do not allow our personal beliefs to interfere with fair representation of the aims of our institutions or the provision of access to their information resources. | ” |

Librarians have often taken a politically neutral stance as a way to gain professional status. In this literature review, the author argues that by not defining their political values, librarians will be influenced by those with economic and political power. This will threaten the public’s access to information while corporations profit. The author disagrees with a prediction by Thomas Suprenant and Claudia Perry-Holmes that libraries can enhance their “institutional status” by charging patrons and offering “information stamps” to those who cannot pay. They believe the profession can stay alive if librarians focus on “efficiency, productivity, and quality control” and compete with the private sector. Librarians must lose their neutral viewpoints and publicly fight for equal access to information.[8]

The author’s argument is made stronger with examples of how information traditionally handled by the government was turned over to private vendors during the Reagan administration. Library services based on ability to pay, which the author compares to this country’s health care system, would greatly accelerate the digital divide. Since this article was written, librarians have become more outspoken. Legislation following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks prompted the ALA to adopt resolutions opposing attempts to restrict access to government information on the basis of national security issues. Librarians’ concerns about the Patriot Act led to proposed legislation and several ALA policies urging user privacy and open access. Librarians are fighting the government for the public’s sake, but they must act before access is threatened, not after it is denied.

Excellence in the profession

[edit | edit source]| “ | We strive for excellence in the profession by maintaining and enhancing our own knowledge and skills, by encouraging the professional development of co-workers, and by fostering the aspirations of potential members of the profession. | ” |

Other Codes of Ethics

[edit | edit source]Society of American Archivists Core Values Statement and Code of Ethics

[edit | edit source]http://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics

The Hacker Ethic

[edit | edit source]Hacker ethic is a term for the moral values and philosophy that are standard in the hacker community. The early hacker culture and resulting philosophy originated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the 1950s and 1960s. The term hacker ethic is attributed to journalist Steven Levy as described in his 1984 book titled Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. The key points within this ethic are access, freedom of information, and improvement to quality of life.

As Levy summarized in the preface of Hackers, the general tenets or principles of hacker ethic are:

- Sharing

- Openness

- Decentralization

- Free access to computers

- World Improvement

In addition to those principles, Levy also described more specific hacker ethics and beliefs in chapter 2, The Hacker Ethic:

Access to computers

[edit | edit source]| “ | Access to computers - and anything which might teach you something about the way the world works - should be unlimited and total. Always yield to the Hands-On Imperative! | ” |

Information should be free

[edit | edit source]| “ | All information should be free: Linking directly with the principle of access, information needs to be free for hackers to fix, improve, and reinvent systems. A free exchange of information allows for greater overall creativity. | ” |

In the hacker viewpoint, almost any system could benefit from an easy flow of information, a concept known as transparency in the social sciences. This is only limited by a concern for maintaining the privacy of certain information, such as medical information. This concept can be seen as roughly analogous to the concept of Intellectual Freedom in the ALA's documents.

The Free Software Foundation notes that "free" refers to unrestricted access; it does not refer to price.[9]

Mistrust authority

[edit | edit source]| “ | Mistrust authority - promote decentralization: The best way to promote the free exchange of information is to have an open system that presents no boundaries between a hacker and a piece of information or an item of equipment that he needs in [their] quest for knowledge, improvement, and time on-line. Hackers believe that bureaucracies, whether corporate, government, or university, are flawed systems. | ” |

Meritocracy

[edit | edit source]| “ | Hackers should be judged by their hacking, not criteria such as degrees, age, race, sex, or position: Inherent in the hacker ethic is a meritocratic system where superficiality is disregarded in esteem of skill. | ” |

While this is an admirable part of a code of ethics, there is a huge lack of diversity within the hacker community and free culture. The Ada Initiative notes that "[w]omen are one of many groups currently under-represented in several areas of open technology and culture. Recent surveys have shown that around 2-5% of open source developers are women (compared to 20-30% of the larger tech industry), and that women represent just 10-15% of Wikipedia editors."[10] Even though the Hacker Ethic does not place any formal restrictions on participation, it does foster environments in which women are targeted in very specific ways, and attempts to address these issues are seen as censorship.[11]

Art and beauty

[edit | edit source]| “ | You can create art and beauty on a computer: Hackers deeply appreciate innovative techniques which allow programs to perform complicated tasks with few instructions. | ” |

Computers can change your life

[edit | edit source]| “ | Computers can change your life for the better | ” |

Hackers felt that computers had enriched their lives, given their lives focus, and made their lives adventurous.

Sharing

[edit | edit source]According to Levy's account, sharing was the norm and expected within the non-corporate hacker culture. The principle of sharing stemmed from the open atmosphere and informal access to resources at MIT. During the early days of computers and programming, the hackers at MIT would develop a program and share it with other computer users.

If the hack was particularly good, then the program might be posted on a board somewhere near one of the computers. Other programs that could be built upon it and improved it were saved to tapes and added to a drawer of programs, readily accessible to all the other hackers. At any time, a fellow hacker might reach into the drawer, pick out the program, and begin adding to it or "bumming" it to make it better. Bumming referred to the process of making the code more concise so that more can be done in fewer instructions, saving precious memory for further enhancements.

In the second generation of hackers, sharing was about sharing with the general public in addition to sharing with other hackers. A particular organization of hackers that was concerned with sharing computers with the general public was a group called Community Memory. This group of hackers and idealists put computers in public places for anyone to use. The first community computer was placed outside of Leopold's Records in Berkeley, California.

This second generation practice of sharing contributed to the battles of free and open software. In fact, when Bill Gates' version of BASIC for the Altair was shared among the hacker community, Gates claimed to have lost a considerable sum of money because few users paid for the software. As a result, Gates wrote an Open Letter to Hobbyists.[12][13] This letter was published by several computer magazines and newsletters, most notably that of the Homebrew Computer Club where much of the sharing occurred.

Hands-On Imperative

[edit | edit source]Many of the principles and tenets of hacker ethic contribute to a common goal: the Hands-On Imperative. As Levy described in Chapter 2, "Hackers believe that essential lessons can be learned about the systems—about the world—from taking things apart, seeing how they work, and using this knowledge to create new and more interesting things."

Employing the Hands-On Imperative requires free access, open information, and the sharing of knowledge. To a true hacker, if the Hands-On Imperative is restricted, then the ends justify the means to make it unrestricted so that improvements can be made. When these principles are not present, hackers tend to work around them. For example, when the computers at MIT were protected either by physical locks or login programs, the hackers there systematically worked around them in order to have access to the machines. Hackers assumed a "willful blindness" in the pursuit of perfection.

This behavior was not malicious in nature: the MIT hackers did not seek to harm the systems or their users (although occasional practical jokes were played using the computer systems). This deeply contrasts with the modern, media-encouraged image of hackers who crack secure systems in order to steal information or complete an act of cyber-vandalism. Dorothy Denning notes that even hackers who crack secure systems illegally are often motivated by personal morals and beliefs, rather than by malice. [14]

Community and collaboration

[edit | edit source]Throughout writings about hackers and their work processes, a common value of community and collaboration is present. For example, in Levy's Hackers, each generation of hackers had geographically based communities where collaboration and sharing occurred. For the hackers at MIT, it was the labs where the computers were running. For the hardware hackers (second generation) and the game hackers (third generation) the geographic area was centered in Silicon Valley where the Homebrew Computer Club and the People's Computer Company helped hackers network, collaborate, and share their work.

The concept of community and collaboration is still relevant today, although hackers are no longer limited to collaboration in geographic regions. Now collaboration takes place via the Internet.[15]

Protocols for Native American Archival Materials

[edit | edit source]The Protocols for Native American Archival Materials is a list of best practices for non-tribal institutions that hold Native American archival materials. The protocols have been pretty controversial, partly because of the cost involved; the archivist at the University of Washington said that he would need to hire at least one full-time staff member whose sole job would be ensuring compliance with the protocols.[16] But the main reason is that it goes against a lot of traditional (European) LIS values, such as Universal Access.

Most of the document is about opportunities to collaborate and consult with tribal leaders about the care of materials in archives. However, the short sections on "Accessibility and Use" and "Culturally Sensitive Materials" state that "For Native American communities the public release of or access to specialized information or knowledge—gathered with and without informed consent—can cause irreparable harm. Instances abound of misrepresentation and exploitation of sacred and secret information." As such, the protocols establish expectations of repatriation of certain materials, and allow Native American communities to restrict access to formerly open collections, stating that "[a]ccess to some knowledge may be restricted as a privilege rather than a right."

Another part that bothered some was in the context section, which suggests cataloging practices for describing materials containing pejorative content. I really liked a lot of the suggestions (e.g. one of their sample notes: "The [tribal name] finds information in this work inaccurate or disrespectful. To learn more contact ...."), which I felt added more information for catalog users. At the same time, I felt challenged by other suggestions that involved removing certain content (i.e. their suggestion that librarians "remove offensive terms from original titles and provide substitute language" in catalog records). I understand where this is coming from -- I wouldn't want to look up a book about a community I belong to, only to find words ridiculing that community and challenging its right to exist -- but it also totally challenges my "accept no censorship! Provide lots of access points!" mindset. [17]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Finks, Lee W. “Values Without Shame.” American Libraries 20 (1989): 352–356.

- ↑ Sager, D. (2001). The Search for Librarianship's Core Values. Public Libraries, 40(3), 149-53.

- ↑ American Library Association. (2009). B.1 Core Values, Ethics, and Core Competencies. In Policy Manual. American Library Association. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/aboutala/governance/policymanual/updatedpolicymanual/section2/40corevalues

- ↑ Ranganathan, S. R. (1963). The five laws of library science. Bombay, New York: Asia Pub. House.

- ↑ Gorman, Michael. "Five New Laws of Librarianship." American Libraries 26 (September 1995): 784-785.

- ↑ Swan, John. "Untruth or Consequences." Library Journal 111 (July 1, 1986): 44-52.

- ↑ Dorman, David. “Open Source Software and the Intellectual Commons.” American Libraries 33, no. 11 (December 2002): 51-54.

- ↑ Blanke, Henry T. "Librarianship and Political Values: Neutrality or Commitment?" Library Journal (1989): 39-43.

- ↑ Stallman, R. What is Free Software? (2011, November 29). www.gnu.org. Retrieved from http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html

- ↑ FAQ. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://adainitiative.org/faq/

- ↑ Reagle, Joseph. "“Free as in sexist?” Free culture and the gender gap" First Monday [Online], Volume 18 Number 1 (30 December 2012)

- ↑ Charles Leadbetter (2008). We-Think. Profile Books.

- ↑ Fiona Macdonald (12 March 2008). "Get a fair share of creativity". Metro.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Denning, D. Concerning Hackers Who Break into Computer Systems. (1990, October). Retrieved from http://www.cs.georgetown.edu/~denning/hackers/Hackers-NCSC.txt

- ↑ Levy, Steven. (1984, 2001). Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution (updated edition). Penguin. ISBN 0-14-100051-1

- ↑ Bolcer, John. The Protocols for Native American Archival Materials: Considerations and Concerns from the Perspective of a Non-Tribal Archivist. Easy Access, January 2009, p.3.

- ↑ http://www2.nau.edu/libnap-p/protocols.html

Information Policy

[edit | edit source]Librarians are far from the only players in today's Information Age. A huge number of people and organizations have a say in how information is created, used, stored, accessed, and disseminated. Each of these parties is influenced by widely divergent goals, world views, and professional ethics.

These divergent viewpoints often come to the fore in debates over Information Policy. An information policy is a public law, regulation or policy that encourages, discourages, or regulates the creation, use, storage, access, and communication and dissemination of information.[1]

Librarians and other information workers are often involved in creating and transforming information policy, and invariably feel the effects of these policies. This chapter will discuss a number of Information Policy debates of particular interest to the LIS community.

After reading this chapter, students should be able to articulate how libraries

- are governed and funded

- establish and uphold policies

- develop collection development policies

- defend access to information in both physical and electronic media

- navigate restrictions from copyright law

- protect patron confidentiality

- navigate policy exceptions

- establish fine and fee structures

- make decisions regarding staff tasks and responsibilities

Collection development

[edit | edit source]Collection development is the process of planning and building a useful and balanced collection of library materials[2]. Collection development policies provide guidelines for people who select Information resources for library collections, and can also be used to evaluate selectors' choices, to see if they were indeed appropriate for the library's collection.

Public libraries particularly face a "quality vs. demand" problem. Librarians are experts in book selection, and have tools, such as professional reviews, to guide them in choosing good books for their collections. However, this does not always mean that their selections are popular with their patrons.

The tension between "quality" and "demand" is often discussed in reference to the case of the Baltimore County Public Library's approach to collection development from the 1980s. When the library considered the fees they were paying to convert to online records, they began to wonder if every item was earning its keep. They checked circulation statistics for each item. Material that didn't circulate frequently enough was withdrawn. More attention was paid to areas of the collection that circulated well. More copies of bestsellers were purchased.

This approach was criticized as not being actual collection development, but just mindless reading of statistics. In an article for Library Journal, Nora Rawlinson, then head of materials selection at Baltimore County Public Library, admitted that it is easy to select popular items, but other material is carefully considered before being purchased for the collection. Esoteric material is rejected and fair service to patrons is considered when selecting. The diverse interests of their patrons can be met because they reduced staff and increased the book budget. The approach was successful: surveys showed that patrons were satisfied, and the library received a significant number more interlibrary loan requests than it made. The fears that the library would devolve into a collection stuffed with bestsellers and little material of real value were unfounded.

Although these collection practices were originally controversial for some libraries, Baltimore County's choice to use a combination of popularity (as represented by circulation statistics) and professional judgement has been widely adopted by many public libraries [3].

Confidentiality

[edit | edit source]The 2001 USA PATRIOT Act has changed how the United States Federal Government can obtain information. The Federal Bureau of Investigation has used the act to ask libraries which books patrons checked out, what databases patrons used, and what reference questions they asked. Ultimately, it requires a court order for libraries to turn over such records and information about patrons. A court decision in Colorado ruled that an adversarial hearing was allowed before a search warrant could be enacted. The PATRIOT ACT permits surveillance, allows for searches without probable cause, and enforces secrecy. All the FBI has to assert in its investigation is that terrorism is involved.

Library staff members should keep in mind that they should not turn over records to anyone without a warrant. In an article for Library Journal, Mary Minow suggests that all libraries have a plan involving staff training, supervising, having a lawyer present if a warrant has been issued, and procedures for handling the requests for information. Is library patron record privacy trivial compared to stopping terrorism? Several organizations asked for an account by the Department of Justice of the investigations carried out by the FBI since the passing of the Patriot Act. At the time of Minow's article, the information requested was termed "classified" and not available to the public [4].

Control of information

[edit | edit source]This editorial states the situation of three specific libraries in Ohio whose hazardous materials emergency plans were removed without notice and without due cause by agents of the Department of Homeland Security. The pretense given by the agents in viewing the plans was that they were there to update it; instead, they took the plans to be stored at a Homeland Security office, where “proper ID may be required” for viewing. Since the areas affected were at risk for terrorist activities in that there was an oil refinery and a tank manufacturing plant in the area, the affected librarians did not necessarily take offense to the removal of these documents given the political climate, but rather the way the information was unceremoniously taken from them.

To remove information that could be vital to some, yet be used as a dangerous tool by others walks a fine line between looking out for the public good and censorship. The Department of Homeland Security manhandled this situation by treating the librarians, and indirectly their patrons, as bothersome pests because of a need to possess information. In the class discussions, the topic of information as a commodity always comes to the issue of who should control information. All parties involved have their own agenda, and in this case the government may have cloaked their desire to remove potentially damaging environmental data under the guise of preventing another terrorist attack.[5]

Copyright

[edit | edit source]How does copyright apply to libraries?

- Libraries are often the only entities that provide access to the vast majority of copyrighted works before the expiration of the copyright, and to works that lose commercial vitality before the copyright expires (i.e. go out of print but are still legally protected).

- First sale doctrine (1908) enables libraries to lend books and other resource

- Except software gets dicier, because of End-user license agreements (EULAs)

- Fair use allows for the use of (usually tiny snippets of) copyrighted works for purposes of criticism, comment, news reporting, scholarship, or research.

- Libraries are permitted to make reproductions of copyrighted works for preservation and replacement purposes.

- Libraries can aid in the transformation and reproduction of copyrighted works for users with disabilities.

- Libraries often play an archival function with print works. Can they do this in the highly copyrighted, license-agreemented world of electronic information? Electronic resources tend to have a very short shelf life, and may not be archived properly for future use.

- Digital Rights Management technologies often don't recognize any limitations to copyright, and just go ahead and restrict access.

The Teach Act helps redefine the terms and conditions of copyright laws, focusing on copyright protected materials in distance education. The act puts more pressure on the educational institution, rather than the educator; but there are several benefits because of the Teach Act: expanded range of allowed works, expansion of receiving locations, storage of transmitted content, and digitizing of analog works. It is important for educators to be aware of copyright information, the number of students enrolled in class, and the amount of time allotted to view the material. If they are cognizant of them, they will not have to worry about breaking the law. Since distance education is growing, librarians are expected to deal with interlibrary loans more often, amongst other new opportunities, and need to understand the Teach Act too. Kenneth brings up several points that are essential to remember about the Teach Act. Distance learning is growing rather quickly, and is becoming more popular amongst the student population. Because of this rapid growth, librarians are asked to perform several new tasks that coincide with the act. Librarians need to be familiar with the Teach Act, so no laws are broken, and all materials remain protected.[6]

Digital Rights Management

[edit | edit source]In this editorial the authors propose that libraries must be involved in the development of digital rights management policies and the selection and implementation of appropriate technologies, because the interests of libraries are different from the interests of commercial information providers. The core mission of libraries is to offer free access to information rather than on a pay-per-use basis as many commercial entities do. Digital rights management for libraries requires identifying and authenticating rights holders and users, while protecting their privacy and confidentiality. The principles of first sale and fair use must be maintained in the digital environment while preserving authors’ rights, as well. As libraries begin to publish more on the web, their interest in digital rights management will increase.

Libraries already offer many products in a digital form accessible to patrons by remote access after identification and authentication. While the library bears the expense of the product, access is open to anyone who has a valid card. In my opinion, the user identifies this service with the library. I agree that libraries need to be involved in digital rights management so information does not become a commodity that can be accessed only by those who can afford it.[7]

Fines and fine waiving

[edit | edit source]Government information

[edit | edit source]International information policy

[edit | edit source]This article provides a historical perspective on the development of international policies and sanctions regarding the fair and safe trade of information between countries. During the internet’s infancy, the issues regarding keeping privileged information confidential and regulation the economic aspects of electronic information were still being worked out. One of the bodies involved in these issues was called the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). When this editorial article was written in 1985 ways to control and regulate the international flow of information were still being worked out. This article only provides a small glimpse of the issue from a modern vantage point. One would assume that today, more than twenty years later that regulations would now be firmly in place. In order to get a better idea of the evolution of international information policy it would be necessary to read several articles that span the past two decades.[8]

Outsourcing

[edit | edit source]

In recent years, many libraries have explored outsourcing "behind-the-scenes" activities, such as cataloging and book selection, to private companies. A classic example of this was a 1996 decision by Bartholomew Kane, the Hawaii State Librarian, to outsource all cataloging and selection for the libraries in the state to the private company Baker and Taylor. Kane's philosophy in this decision was guided by public surveys which showed a public desire for increased library assistance and longer hours of operation. By outsourcing cataloging and selection, Kane was able to meet both of these public demands.

However, this approach also has its drawbacks. For instance, by outsourcing selection and cataloging, the library loses its autonomy in making differentiated selections to suit their individual populations. Although the State Library argued that it would be in Baker and Taylor's best financial interest to select the appropriate materials, the issue is not entirely resolved. For instance, will the selectors at Baker and Taylor have the same interactions with and knowledge of the public that the librarians would have? Additionally, the state of Hawaii is in a unique situation, as the only state with a state-wide library system, and in a state of geographic semi-isolation from the rest of the country. Applying a blanket solution such as outsourcing some of the traditional roles of the public library is not a catch-all solution for all libraries that need to increase their hours and personnel without increasing their bottom line.[9]

Web content filters

[edit | edit source]

Libraries are one of the primary providers of public Internet access within the United States. American librarians are also ethically bound by the ALA's code of ethics to "resist all efforts to censor library resources." Therefore, when the 2000 Children's Internet Protection Act (CIPA) required libraries and schools to filter web content as a condition for receiving certain federal funding, many in the library community strongly objected. The ALA challenged the act as unconstitutionally blocking access to constitutionally protected information on the Internet. The ALA also noted that E-rate funding, one of the federal funding programs contingent on web filter use, was created to provide Internet access to all communities, including historically underfunded communities. Mandating filters imposes additional financial burdens on the same schools and libraries that the e-rate program was meant to help. Finally, the ALA stated that web filters are notoriously unreliable, with "no filtering software successfully differentiat[ing] constitutionally protected speech from illegal speech on the Internet." The case made it to the Supreme Court, which in 2003, ruled that CIPA was in fact constitutional.

The debate over filtering in the library community is far from over, however. Writing in 2004, Nancy Kranich notes seven reasons filters do not succeed in protecting patrons from offensive Internet material:

- Filters underblock sites that are banned by CIPA

- Filters overblock sites that are legal

- Filter providers cannot review every site

- Filters do not distinguish between users of different ages

- Overriding or disabling filters is time-consuming and costly

- Some users find ways around filters or find access elsewhere

- Filters do not block email, chat rooms or videos

Kranich argues that the best ways to protect consumers are through education, Internet access policies, links to approved, quality sites, and reference assistance. Requiring parental consent for minors to use the Internet, public monitoring, and the use of privacy screens also help protect consumers.[10]

Many in the library community also worried that federal laws such as CIPA could lead the way to even more restrictive laws on the state level. Some libraries filter because violating certain state laws could lead to criminal charges. Most libraries depend on community support and money, so resisting the public’s requests puts libraries’ futures at risk. Would libraries choose filtering if there were no threats of legal action and eliminated funding? If so, what does this say about the ALA’s mission?

However, Hampton Auld takes a different view of filtering. In Auld's article, the Chesterfield County (Virginia) Public Library began filtering all public Internet-access computers after complaints that adults and children were viewing pornographic images. The library observed a reduction in the number of times pornography had to be cleared from screens, a reduction in the number of reported complaints, and an improved library environment, despite mistakes made by the filtering software. Auld argues that filters work in blocking pornography while only slightly affecting access to protected speech. According to Auld, the ALA should revise its anti-filtering policy because filters are more effective than any other ALA-recommended method and the policy is undermining and dividing the profession.[11]

The following table represents arguments for and against filtering requirements from an earlier supreme court case, Reno v. ACLU. In this case, the supreme court sided with the ACLU, unanimously striking down a portion of the 1996 Communications Decency Act (CDA).

| Argument | Defense |

| Filters use keywords. | True, but good filters can turn off keyword blocking and rely on site-selected blocking. |

| Filters block sex education, AIDS info, etc. | Can be set up so only pornographic sites are blocked. |

| Outsiders select material. | Librarians have vendors preselect books. |

| The lists of sites that are banned cannot be viewed or changed. | They are all different. Some have viewable lists, main thing is that it is editable and accurate. |

| Libraries look like "publishers" and can be responsible for its content. | "Good Samaritan" blocking amendment protects libraries if blocking offensive material. |

| Internet is too big and changes too fast to be 100% accurate. | Libraries have to try to be consistent, not ensure appropriateness. |