History of Tennessee/Printable version

| This is the print version of History of Tennessee You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/History_of_Tennessee

Introduction

The origin of the state of Tennessee can be directly linked to the Watauga Association. The Watauga Association was a colony made up of an independently governed group of settlers on the waters of the Watauga and Nolichucky. This group of settlers leased the land from the Overhill Cherokee tribe beginning in 1772. However, the Cherokee claim to the land was ultimately disregarded, resulting in conflict. Due to the conflict with the Cherokee, the settlers of the Watauga Association sent a petition to the Provincial Congress of North Carolina, asking to be taken under the protection of North Carolina. In 1776, the Watauga Association was annexed by North Carolina and by 1777 became Washington County and was placed under a county government within the state. Following 19 years as a Washington County, the name was changed to Tennessee, eventually entering the Union and assuming statehood in July of 1796, becoming the 16th state to do so. The original capital of Tennessee was Knoxville, but it has since been changed to Nashville, the most heavily populated city in Tennessee. Tennessee is nicknamed the "volunteer state" due to their contributions and the number of volunteers the state produced to fight in the War of 1812. Like many other American states, the name Tennessee originated from Native American roots. It came from the name of a Cherokee village that was present at the time of European exploration. The name of the village that the name Tennessee derived from was called "Tanasqui". The meaning of the state has been lost over the years, but many believe it could mean "meeting place","winding river", or "river of the great bend". The original spelling of Tennessee is accredited to James Glen, who was the Governor of South Carolina at the time, and referred to the state in his official correspondence in the 1750s.

Exploration of Tennessee[edit | edit source]

Early Exploration[edit | edit source]

Early exploration of Tennessee would foreshadow future events to come, as the technologically superior Europeans with expansionist ideologies saw an overwhelming opportunity in North America and westward expansion.

Native Americans lived in what is now known as Tennessee for an estimated 12,000 years. Archaeologists have discovered an abundance of artistic and symbolic ornaments scattered throughout the area. Although there is not literature that depicts life before European contact, these archaeological findings point to a rich and prosperous period for the Native Americans which inhabited Tennessee before European contact. In the 1540s, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto led the first expedition into North America arriving in Tampa Bay and traversing into Tennessee. During this early expedition, the explorers came to a village called Tanasi, where the name Tennessee is derived. After these early encounters with the Spanish, the native Chickasaw population in the west and the Cherokee in the east remained largely uncontacted but not undisturbed. The Spanish brought diseases such as smallpox and influenza, killing thousands of native Americans long after the explorers left.

European Contact[edit | edit source]

The first European pioneers who made contact with Native Americans within Tennessee were traders from South Carolina and Virginia. These settlers and native tribes noticed an opportunity with the abundance of wild game in the area and soon thereafter, hunting parties began to track game within the borders of Tennessee. By 1760, hunters and traders had explored most of Tennessee and throughout the decade permanent settlements began to appear. In 1771 a land survey showed these settlements were trespassing on Cherokee lands and breaking British policy subsequently demanding their removal. The Watauga Association was a byproduct of these settlers who leased the land from the Cherokee and formed a self-governing community along the Watauga River. The association lasted more than four years and served as the first independent community free of British rule and served as a stepping stone for the birth of American Independence.

Becoming Tennessee[edit | edit source]

The name Tennessee is derived from the word, Tanasqui, the name of a Native American village. The state flag has three white stars which represent the three political divisions of the state at different periods in time. These stars are bound together by a blue circle that symbolizes the three making one. This design was made by Captain LeRoy Reeves, who was an officer in the Tennessee National Guard. The state song is “Tennessee” written by Rev. A. J. Holt. It was first sung on May 1, 1897, at the opening of the Tennessee centennial at Nashville. Although the song was not legally adopted by the legislature, public sentiment has made it the state song.

The Western and Eastern frontiers, which stretched from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River, had grown in population and economic interest from the 1770s and onward. The dangers associated with boarding native territories and disobeying the crown resulted in the lease of the land from the Cherokees. Six counties were established within the land leased and were all under the jurisdiction of North Carolina from 1777 to 1788. Settlers grew weary of North Carolina's inability to protect them from native attacks. Furthermore, North Carolina was disinterested with the upkeep and expenses of maintaining these settlements and contrastingly the settlers wanted a government to prioritize their primary concerns of safety. The Cumberland pack established a second Eastern frontier and elected a governing body to oversee it. East Tennessee declared for independence, forming a new state called Franklin, under the direction of John Sevier. North Carolina slowly reinserted their present back within Franklin, coupled with territorial disputes with other counties, the state dissolved in 1788. Although the state failed, it showed that settlers of Tennessee were willing to pursue independence demonstrating the validity of their concerns. In 1789, North Carolina ceded the land of Tennessee to the federal government, which named it the Southwest Territory, establishing East, Middle and West Tennessee. These new divisions of Tennessee focused primarily on securing settlers' property and protecting them from native raids. These attacks continued until 1794 when John Seiver, who would become the first governor, led a coalition forcing the natives out of Tennessee. In 1796 with a sufficient population, Tennessee was converted from a territory to a state without a congressional vote.

Tennessee Culture[edit | edit source]

Music[edit | edit source]

Tennessee is considered to be one of the best homes for music, as the state is well known for country, rock, and blues styles of music. Nashville, the capital of Tennessee, has become known as the capital of country music around the world. Much of the tourist industry within Tennessee has been built around country music, including the Country Hall of Fame, Belcourt Theatre, and Ryman Auditorium. The Country Music Awards is held annually in June and attracts thousands of country music fans to the city of Nashville.

Sports[edit | edit source]

Tennesseans have enjoyed partaking in sports since the pioneers. Sports and recreation included shooting matches, hunting, and horse racing. Different parts of Tennessee would partake or excel in certain sports more than others. For example, in the southeastern part of the state, The Great Smokey Mountains offered a preferable place for hiking, horseback riding, and camping. In addition, this region was well suited for hunting, particularly for wild boar, ducks, raccoons, and fishing. For those who preferred hunting smaller animals, they had the option of hunting or capturing muskrats, weasels, squirrels, rabbits, and more. These types of animals were good for providing fur. Northeast of Knoxville, the State Buffalo Springs Game Farm offered a prime spot for hunting birds such as quail and wild turkey. When migrations of waterfowls occurred, they flew over the Mississippi River, giving hunters the perfect opportunity for ducks and geese. For fishing, there were two hatcheries; one in Erwin and one in Flintville. In the mountains' streams, one could find rainbow trout, brook trout, bass, salmon, and catfish in the slower streams located in Cumberland.

Demographics[edit | edit source]

According to the 2010 National Census, Tennessee’s population was 6,346,105 as of April 1st, 2010, with an estimated population of 6,770,010 as of July 1st, 2018. In addition, Tennessee had a population density of 153.9 people per square mile according to the 2010 Census.

Regarding ethnical diversity, 78.5% (approximately 5.2 million people) of Tennessee's population are Caucasian, 17% African American, and 5% Hispanic or Latino. Just 2% are of Asian descent, 0.5% being Native American, and 2% from other countries of origin.

Geography[edit | edit source]

Tennessee is located in the southeastern region of the United States, bordering on eight other American states. These states include Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi to the south, Kentucky in the north, Virginia in the northeast, North Carolina in the east, Arkansas to the west, and Missouri to the northwest. It is the 36th largest state, with an area of 42,022 square miles. The highest point in the state is Clingmans Dome (6,643 feet), which is the highest point on the Appalachian Trail, the longest hiking-only trail in the world. The state's lowest point can be found along the Mississippi river which has an elevation of 178 feet. Tennessee also exhibits many beautiful valleys and coves. These areas hold rich amounts of soil that are essential for fertility in growing crops and other plants. Many of the farms are located in the valleys alongside streams which possess rich soils. Tennessee lacks areas that have leveled land. Most of the Appalachian Mountain Region is too steep for farming and is covered in forests, some not easily able to be reached. Many of these forests have dealt with damage from forest fires.

Compared to the other states in the eastern United States, Tennessee has the most diverse landscape. The majority of the state of Tennessee is covered in mountains and hills. The largest of these mountain ranges being the Cumberland mountains which essentially divide the state into two separate regions, East Tennessee and West Tennessee.

Soil[edit | edit source]

As a whole, the state of Tennessee is extremely cultivatable. Due to the natural division between the two main sides of the state, the east and west each have unique soil compositions. In the eastern part of the state, the soil has uncommon proportions of dissolved lime with nitrate of lime mixed in, making East Tennessee extremely fertile. West Tennessee is equally as fertile, however, the soil has extremely specific strata. The first layer is generally made up of loamy soil, or a mixture of clay and sand. This layer is followed by yellow clay, then a mixture of red clay and red sand. Finally, at the lowest layer, there is white sand.

The state also has the greatest variety of mineral resources of any other state, the most significant is bauxite barite, clay, copper, coal, marble, iron, zinc, and phosphate.

Rivers[edit | edit source]

An important geographical aspect of Tennessee is the extensive networks of waterways all over the state. The most significant of these is the Tennessee River which spreads throughout the state and has been a hub for the transportation of goods within Tennessee from as early as 1700. The Tennessee River also allowed for the transportation of goods and people out of the state and into other states such as Alabama. Over time the river has also allowed for much easier transport to the Gulf of Mexico. Another major river that exists within the state is the Cumberland River, which has also been a major outlet for commerce in Tennessee.

Caves[edit | edit source]

Tennessee is home to over 9000 caves which have seen many different uses over the years. The caves were first used for mining, mainly the mining of saltpetre. The next industrial use for the caves was for the purpose of creating moonshine whiskey during the prohibition. The caves are now used as a tourist attraction, in which tours will walk and explore through.

Economy[edit | edit source]

Tennessee’s geographic location plays a significant role because it is centrally located. This has helped to create a strong agricultural and manufacturing economy in the past and present. During modern times, the state's centralized location makes it a strong economic centre for agriculture, manufacturing, and logistics due to easy access to various methods of shipping products, including road, rail, and water. In fact, the multinational courier company FedEx Corporation is headquartered in Memphis, Tennessee.

The earliest communities in east Tennessee settled near streams, creeks, and rivers in both the Cherokee period and the 18th century European settlement period. Many Tennessean pioneers were farmers who produced many of their own goods. The early settlers made cloth and yarn using a spinning wheel, and fabricated farming tools and furniture. Additionally, they used processed hides to make clothing. Most of the early industrial activity took place in towns; Knoxville produced cotton, leather goods, and flour. The South’s first cotton mill was established in the early 1790s near Nashville, and Memphis became the nation's largest cottonseed processor.

Agriculture[edit | edit source]

The state has an ideal climate for crop growth. The eastern region consists of hills and mountains. The west contains raw crops, and fertile rolling land is found in the middle. Corn and soybeans are Tennessee's primary crops. In addition, their tobacco production ranks third in the United States. 80 percent of the land is used for agriculture, including forestry, with the average farm size being 138 acres.

Timber[edit | edit source]

Tennessee is also the home to a large area of over 14 million acres of forest that accounts for just over half of the state. Between the early 1950s and 2000, there was a 400% increase in forestland that is classified as hardwoods. Although the timber industry continues to increase the value of forest products in the economy from 18.2 billion to 21.7 billion, the share of the state's economic contribution dropped from 9.8% to 6.6%. Factors such as urbanization and population growth are having a significant impact on the industry. Private landowners owned just 37% of forest land in 2002, which is less than half of what it was fifty years earlier. Tennessee’s Forests have an abundant number of trees with over 150 different species followed by possessing many kinds of soil. When settlers first discovered Tennessee it was originally covered in 26-27 million acres of forests. The only things that weren’t inhabited by forests were mountain tops, mountain sides, swamps, and the little amount of land that had been cleared by the early settlers and Indians. The trees inside these forests grew to be very large. Short leaf pine can grow up to 100 feet high and 12 feet in circumference. Yellow poplar can grow up to 150 feet and 30 feet around. This made everyone in Tennessee at the time “forest people” as majority of all settlements were in forests. This caused for a very lonely time of living as many people lived alone in the woods. Typically, women would go into the woods and search for nuts and berries for food, also different coloured mosses for dyes. Herbs, roots and different tree barks were found for the intent to make medicines.

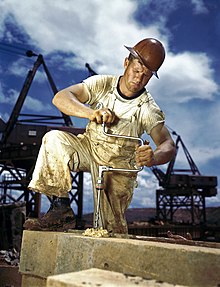

Automobile and Parts Manufacturing[edit | edit source]

The centralized location of the Tennessee Valley made it an ideal location for manufacturing. In the 1990s, the automobile industry took off in the state with the opening of Nissan and Saturn plants near Nashville and a Corvette plant just north over the state border in Kentucky. In 1998, car and truck assembly contributed to nearly 20% of all manufacturing in the state. Tennessee was the third largest auto producer in the nation despite it only being a part of the state's economy for fifteen years. The automobile industry continues to thrive in the state supplying 160,000 jobs per year and providing $6.5 billion in salaries.

Tariffs as a Potential Danger[edit | edit source]

The US administration has proposed tariffs on imported automobile parts which would have a significant impact on the state's primary automobile company Nissan, which is based out of Japan so many parts for their vehicles are imported. With the state producing 6.7% of all vehicles in the US, automobile companies have expressed dislike for the proposed tariffs as it will lower their profits. In addition, rewarding employees with bonuses and raises will become much more difficult. Lastly, not being able to employ as many people would have negative implications for the state's economic well being.

Music in Tennessee[edit | edit source]

Political Implications[edit | edit source]

Music in Tennessee played a significant role in modelling the relationship between white and black Americans, ultimately transforming the state’s political landscape. Author Mark Johnson stated that when settlers first contacted Africans, they remarked that Africans possessed a natural musical ability and made better music than all other races. In later years, Thomas Jefferson expanded on this idea by saying that when it comes to music, blacks are more generally gifted than whites, having more accurate ears for tune and time. Consequently, white politicians saw an opportunity in employing African American musicians. In an effort to attract key votes, white southern politicians hired black musicians to perform and campaign on their behalf. Through this, African American musicians provided better access to black audiences, therefore promoting greater opportunity for white political figures and organizations.

Social Implications[edit | edit source]

While this music played a significant role in shaping Tennessee’s political landscape, its social implications were even greater. It allowed black musicians to manipulate the white southerner’s stereotypes of African Americans, thus more effectively resisting racial oppression in Tennessee. African American musician William Christopher Handy was among the most noteworthy individuals to promote music as a gateway for social justice and racial equality. While he used his music to assist white politicians in gaining political influence, he mainly used it as an opportunity to obtain power for himself and his entire race. By listening to this music, many white Tennesseans began characterizing the African American people as being joyful, fun-loving individuals, therefore lessening the destructive stigmas white Americans attributed towards African American Tennesseans.

Economical Implications[edit | edit source]

Through this evolving predisposition, white Tennesseans started to recognize the monetary value in African American musicians. White slave masters coveted the entertainment value of black musicians, hiring them out to other white masters. It became commonplace for black musicians to perform at white parties in early 20th century Tennessee. To demonstrate this idea, in 1925, the Ku Klux Klan attempted to host a black band at one of their rallies. However, for the sake of embracing music as a form of resistance to racial oppression, the African American band refused to perform.

Music as an Outlet[edit | edit source]

Many white Tennesseans capitalized on African American music to satisfy corporate greed and reinforce political agendas. Still, black Tennesseans were able to benefit from it as well. African Americans used music as an opportunity for self-expression. In addition, African slaves used music to make their work more endurable while also reinvigorating their African culture in the new world. Furthermore, they used music as a form of safe communication. Slaves would express various ideas and emotions in the form of song, ultimately disguising messages that could have had dangerous implications if realized by their white masters. Using music and song as a second language, black Tennesseans were able to more efficiently facility group solidarity in a time of oppression and intense racial disparity.

Later in 20th century Tennessean history, black musical culture and community became increasingly important in the city of Memphis, Tennessee. With a centralized focus on the black musical community, African American disc jockey Nathaniel D. Williams played a significant role in communicating the civil rights of black Memphians. Furthermore, Williams expressed that historically speaking, singing had been the only effective means of communication at the disposal of black Tennesseans. As seen throughout history, African American music played a significant role in transforming the political and social landscape of Tennessee.

Conflict with the Native Americans[edit | edit source]

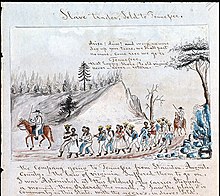

Soon after Tennessee became a state, a conflict started with the Native Americans tribes that they were sharing the land with. The main groups that were living on the land at the time were the Creek, the Chickasaw, and the Cherokee. Much of the conflict that was occurring was over the property of the land, as many of the citizens were becoming property hungry. Eventually, the Natives were forced off the land and had to travel to a designated "Indian Territory". To enforce this, the Indian Removal Act was established by President Andrew Jackson, the former first senator of Tennessee. This act forced all natives living east of the Mississippi River to move west of it. This resulted in around 100,000 Native Americans walking west on what is now called "The Trail of Tears". The trail is 5043 miles long and runs over nine states.

The War of 1812[edit | edit source]

War of 1812 showed how capable the relatively new state of Tennessee was, politically and militarily. The War of 1812 was a conflict between the United States and Great Britain. The United States and Great Britain had experienced mounting tensions since the American revolutionary war. British ships would stop American ships at sea, search them and sometimes kidnap sailors and force them into their navy. Additionally, many Americans felt the British were encouraging uprisings by Native Americans. There was a particular concern in the upper Mississippi Valley, where a Shawnee leader named Tecumseh was trying to organize the tribes in a joint resistance against all white settlers. Many Americans, including Tennesseans, saw this as the result of British provocation. In June of 1812, President James Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war. All of Tennessee’s representatives voted for the motion. Tennessean Congressman Felix Grundy is seen as one of the main influences in Congress’ decision to declare war on Britain.

Since the majority of the battles in the War of 1812 were fought along the Canadian-American border, Tennessee's involvement in most of these battles was extremely limited. However, by 1813, President James Madison called upon Andrew Jackson and the state of Tennessee to protect the lower Mississippi region. Large quantities of Tennessean men willingly volunteered, earning Tennessee the nickname, “The Volunteer State”.

The American Civil War[edit | edit source]

On June 8, 1861, the state of Tennessee ratified a resolution of independence with a vote of over 105,000 to 47,000, allowing Tennessee to become the last state to secede from the Union and join the New Confederacy. On May 7, 1861, Tennessee entered into a military league with the Confederate government, showing the state’s full commitment to aiding the Confederacy in the American Civil War.

Tensions grew as the grand divisions within Tennessee were politically divided as West and Middle Tennessee supported the Confederates and East Tennessee supported the Union. Tennessee provided an estimated 150,000 soldiers to the Confederacy, second only to Virginia, and 31,000 Union soldiers, more than all of the confederate states combined. Furthermore, this is not including Andrew Jackson's 20,000 unionist militia or men that enlisted out of state. Tennessee’s sheer number of men able to fight compared to other seceding states. The Mississippi river's neutral location and the agricultural resources mainly in Middle Tennessee, made the state of utmost importance for the Confederacy to maintain power and for the Union to take it away.

Tennessee was extremely important strategically for the Confederacy during the American Civil War. The state's abundance of natural resources was one of the primary reasons why it was so important. Lower Middle Tennessee, in particular, possessed an abundance of extremely fertile farmland, essential for feeding armies all over the country.

Along the Cumberland River, the Confederacy situated its most important gunpowder mills, an invaluable resource in times of war. The city of Memphis was also the Confederacy’s most important centre for war production, making Tennessee one of the Union’s principal targets.

The second most battles in the Civil War would occur in Tennessee. Starting with the Battle of Mill Springs in 1862 and ending with the battle of Nashville in 1864, thereafter shifting the main focus of the fighting to Georgia. Fighting large battles within Tennessee had ended and left Middle Tennessee ruin.

Although confederate sentiment was still alive in these regions, open support was dangerous. East and Middle Tennessee were occupied in 1863 by Federals and the damage was devastating not only from battles, but from thousands of soldiers residing in the state, as lawlessness was present during the war. This massive number of soldiers supplied and having the second most battles within its borders meant many men did not return home and the few that did went home to an unrecognizable state. This makes it clear why Tennessee was in ruins after the war and why it would take years for the state to overcome the burdens of the Civil War.

World War Two[edit | edit source]

Nearly a century after the American Civil War concluded the state of Tennessee played a massive role, if not the deciding role in World War 2. Oak Ridge, Tennessee is known as the “secret city” because many of the citizens living there, and elsewhere in the country, did not actually know what was occurring there at the time of the war. The reason for the secrecy is because it was the location where the Manhattan Project was being developed by American, British and Canadian scientists. The Manhattan Project was the development of the first atomic bomb that the world had ever seen. The first of the two bombs developed dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945, and the second was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945. The war finally came to an end with Japan surrendering on August 15, 1945. These bombs remain to be the only two nuclear bombs ever used in war.

Tennessee Disasters[edit | edit source]

Tennessee has gone through many disasters including natural, technological, and societal disasters. Some of the natural disasters include Droughts and severe heat waves, earthquakes, wild wind fires, slow rising flash floods, tornadoes and straight-line winds, and winter storms. One example of a natural disaster would be the drought of 1930 to 1931 Some of the technological disasters the Tennessee faced are explosions, structure fires, mining quarry disasters, structural failures, airplane crashes, highway accidents, railroad accidents, river boat accidents. An example of a technological disaster would be Jellico railroad yard explosion. Some of the societal disasters that Tennessee had were, labour wars, strikes, and economical disasters, race riots and radical violence, and bloody family feuds and political conflicts. An example of a societal disaster would be the Memphis sanitation worker strike.

Indigenous "Tennessee" (to 1800)

Indigenous Tennessee[edit | edit source]

Prior to European settlement in Tennessee in 1541, the land was known by Indigenous tribes as the "Territory South of the River Ohio". This point in time can be referred to as "Indigenous Tennessee."

The Paleoindians[edit | edit source]

Archeological evidence suggests that around 13,000 years ago, the Paleoindians crossed over the Bering Strait via a land bridge that connected Russia to North America. These early ancestors reached the fertile woodland and prairies of the Territory South of the River Ohio in small family groups of 25-50 individuals. Their movement was based on the movement of the animals they hunted, such as mammoth and giant bison, and they used flint stone to fashion tools and weapons for hunting.

Indigenous Tribes in Tennessee[edit | edit source]

The Cherokee Tribe[edit | edit source]

The Cherokee dwelled in the valley of East Tennessee, and were known by white settlers and other tribes as being cruel warriors with an efficient political organization. Since women had the most power and independence in the tribe, chiefs were elected by the matrons. Being an Iroquois speaking people, they were one of five tribes to establish the Iroquois Confederacy in 1570, which was created to bring peace and unification amongst the tribes. Although the Cherokee were a powerful tribe, by the 1750s their population had significantly declined due to disease and conflict brought by the English and French settlers.

The Muskhogean Tribes[edit | edit source]

The Muskhogean race is comprised of many tribes, three of which are the Chickasaw, Creek, and Koasati, all of whom occupied parts of Tennessee. Being sedentary, they occupied villages where women were farmers and gatherers of squash, beans, and corn, while men were sent off to hunt. The Creek Tribe in particular had many conflicts with the Cherokee causing the Creek-Cherokee War, a four decade long cycle of revenge warfare. Alternatively, the Chickasaw were often at war with the Choctaw tribe who occupied the Mississippi River Valley area and, towards the end of the 18th century, they alternated between being allied with and being at war with both the British and French.

The Quapaw Tribe[edit | edit source]

The Quapaw Tribe, belonging to the Dhegian-Siouan speaking people, were believed to have migrated down the Ohio River Valley around 1200 CE, although this is widely debated. Due to their migration patterns, other tribes and eventually the French called them “Akansea” or “Akansa” meaning “land of the downriver people." With a small population of no more than 6,000 people, this community built houses containing multiple families, and were mostly farmers and gatherers of corn, maize, beans, and squash. They also created canals and used nets for easy access to fish. The Quapaw were a creative people, often making pottery and elaborate outfits for ceremonial purposes.

The Shawnee Tribe[edit | edit source]

This Algonquin-speaking tribe were intelligent, sedentary farmers of maize and rice who made use of advanced tools such as spades and hoes. As one of the first tribes to come in contact with white settlers, they were friendly with the French but at war with the British. Although they lacked tribal organization, they were advanced in art and able to make soft clothing, had many legends and myths, and documented their lives through picture writing.

The Yuchi Tribe[edit | edit source]

Discovered during the Spanish de Soto expedition of 1539-1543, the Yuchi tribe was a Uchean speaking tribe, a distinct language unrelated to the other tribes. They had a relatively small population of around 5,000 individuals. This tribe settled in permanent towns with women farming corn, squash, and beans, while men hunted elk, bear, and deer. By 1730, only 130 Yuchi men were recorded in Tennessee as they had been forced to migrate due to ongoing wars with the Cherokee.

Rituals and Practices[edit | edit source]

From the beginning, Native Americans have used myths, stories, and legends to communicate their respect and wisdom for animals and nature. One of the most celebrated rituals practiced by all Native Americans is the Green Corn Ceremony, a time for thanksgiving and renewal, which coincides with the ripening of the autumn crop. Tobacco is a plant with many ritualistic purposes in Native American culture. The smoke is believed to connect this world with the supernatural, making tobacco sacred. It was often used in agreements between tribes as offerings, payments, or to show respect. It was also used medicinally in healing and curing, as well as to suppress hunger.

Indigenous Economy[edit | edit source]

Agriculture & The Agri-Economy[edit | edit source]

The economy and trade of the Indigenous people of the land that would become the state of Tennessee is unique. Since many of the local tribes descended from Mississippian culture, they were simultaneously an agrarian society, and a hunter-gatherer society. This includes the Muscogee, Chickasaw , Choctaw, and Cherokee tribes. Over the next few centuries, the hunter-gatherer economy shifted from seasonal base camps to more dense populations in semi-permanent encampments on prime river-ine sites. They primarily hunted deer, bear and turkey using the atlatl (a type of throwing stick) to propel their spears with great force. The more drastic dietary changes came with the large-scale gathering of fruits and nuts and the consumption of fish, mussels, snails and turtles. This implies that a fair portion of their economic power would have been involved in the trade of food and animal products, such as hides, furs and other food products and by-products.

These tribes were also matrilineal by nature, meaning that they placed great importance on a woman’s role in her tribe. With this in mind however, tribes still held a system of basic gender roles. Women were responsible for the farms and agrarian life, this included making the tools they would implement in their farming techniques. They also supplemented the trading of crops with handicrafts such as woven baskets and pottery. These products would play a very important role in trade, as these goods bolstered the local economy, allowing the tribes to exchange resources and gather what supplies they might need, even if they came from abroad. Trading within the tribes was a fairly common occurrence, evidence of this can be seen in several European goods that were traded from tribes near the Atlantic and Gulf coasts into Tennessee, some time during the Protohistoric Period. As Europeans progressed further into North America, and the “white man’s” presence was becoming increasingly profound, the local tribes opened up their trading with the British, French and Spanish that frequented the area. New goods, such as metal tools, textiles, and firearms were integrated into the economy, and quickly became regarded as luxury items, highly prized by the Indigenous people of Tennessee. Soon, the English colonists of Carolina had built up a near-monopoly over trade with the Cherokee, Creeks, and many other tribes stretching as far as the Mississippi. However, this monopoly by the big merchants of Charleston would not last forever. In the end, the debate over how trade should be conducted would lead to the end of proprietary government and its associated dominance over trade with the Cherokee, and the regulatory system would return. In the beginning of the 1700s, until roughly 1750, the natives either took their goods to Savannah Town, at the falls of the Savannah River, or exchanged their goods with the traders in established posts at Cherokee towns.

Slavery[edit | edit source]

Another portion of the economy that saw a heightened emergence upon arrival of the European settlers was the slave trade. Many of the local tribes, primarily the Cherokee, Choctaw and Chickasaw, began to ally themselves with either the French or the British, as the Spanish began to cede from the area.

The Cherokees themselves found themselves forced to move, in part due to the increasing pressure from tribes on both the east and north who, armed with guns and weapons, had begun taking Native slaves for English traders in South Carolina and Virginia. These slaves were captives of war and raids, and though traditionally held no value to the tribes, gained economic value as the British began to purchase them. To the English, the bounty and plenty of North America was hampered only by the lack of labor to work the land, and these captive warriors provided a cheap form of knowledgeable labor. One of the largest contributors to this purchase of Native slaves was the Cherokee by the British. Evidence shows that the Cherokee warriors began selling slaves to the British in the early 17th Century, and would become their steadfast allies in their fight with the Tuscaroras, and in the Yamassee War soon after. Other tribes such as the Chickasaw also took part in slave trade raiding their enemies, the Choctaw, and giving themselves more control over prized hunting lands. The capture and selling of slaves would help these tribes gain resources and other items to aid in their survival.

Admission to the Union[edit | edit source]

Tennessee and The Constitution[edit | edit source]

The admission of Tennessee into the Union marked Tennessee’s shift from a territory to a state and marked significant changes for the Indigenous nations who lived in the region. In 1789, North Carolina ceded its Western territory to the United States, which set the region on the path to statehood. Tennessee was admitted on June 1, 1796 as the sixteenth state in the United States. In the state of Tennessee, Knoxville became the first capital city, John Sevier became the first governor and Andrew Jackson became the first congressman. This new statehood meant the creation and adoption of the Constitution of Tennessee and integration into the rest of the United States. The Constitution of Tennessee was created in 1796 and was comprised of eleven articles which outlined the structure of the government, the government institutions and the powers and limitations that could be exercised by the government. The Constitution also outlined the rights of the state’s citizens, although it is evident that the constitution did not apply to all. Article III, Section I outlines who is able to vote: “Every freeman of the age of twenty-one and upwards, possessing a freehold in the county wherin he may vote…”(Swindler, Chronology and Documentary Handbook of the State of Tennessee. When Tennessee was first admitted, inequalities that existed previous to statehood were now entrenched in legal doctrine. Article XI of the Constitution of Tennessee is the Declaration of Rights, and like the rest of the constitution, did not extend to all citizens. Women, Indigenous people, and African Americans were largely excluded or were not even recognized by the newly formed state. The Tennessee Constitution remained consistent with the Constitution of the United States. The admission of Tennessee into the Union was an important event in American history and was a beneficial addition to the United States, but not all Tennesseans experienced or received the benefits from this newly formed state.

Indigenous Peoples and Tennessee's Statehood[edit | edit source]

The Indigenous people inhabiting the newly formed state included the Chickasaw, Choctaws, Cherokee, and Muskogean. Leading up to Tennessee’s admission, what is now present day Tennessee, was considered a Southwest Territory and the Indigenous were subject to policies that pertained exclusively to them. As early as 1785, treaty provisions were put in place which granted the United States the “right of managing all (Indian) affairs." Although negotiations did take place with various groups, such as the Cherokee, and treaties were created, this did little to prevent the relocation of Indigenous people and did even less to protect their ancestral lands and ways of life. The Indigenous population were continuously forced off of their ancestral homes and were pushed further down the Tennessee River. This allowed for permanent settlement for the white American population, at the expense of the Indigenous peoples who used to have claim to the territory. These Americans and frontiersmen could now access and begin farming on the land that was previously disputed. In 1789, just six years before statehood, William Blount was appointed as “governor and superintendent of Indian Affairs for the territory," by President George Washington. The jurisdiction put in place had a central focus on ‘civilizing’ the Southwest regions Indigenous groups by “encouraging agriculture and useful arts.” Policies and negotiations with certain Indigenous groups such as the Cherokee, did take place, but ultimately the white settlers took precedence when it came to land claims and the buying and selling of property. Sentiments towards the loss of Indigenous lands and territories can be expressed through a group of various Cherokee chief’s address to Governor William Blount:

…is it because we are a poor broken nation not able to help ourselves? or is it because we are red people? Or do the white people look on us as the Buffaloe and other wild beasts in the woods, and that they have a right to take our property at their pleasure? Though we are red we think we were made by the same power, and certainly we think we have as much right to enjoy our property as any other human being that inhabit the earth. If not we hope our brother will not screen anything from us, if we are to have our land taken away at the pleasure of any white man that chuses to go and settle on it.

The admission to the United States only strengthened the position of government officials and the legitimacy of the various policies. The events that led up to the admission of Tennessee in 1796 into the union had negative effects on the Indigenous population and often times led to violent clashes between the Indigenous and the white American populations. In the years following Tennessee becoming an official state, the Indigenous population continued to be subjected to unfair policies and regulations. The Constitution of Tennessee in 1796 also affirmed the inequalities in the newly formed state by only allowing political activity for a select few people. All of the policies and limitations for a number of people in the state was only a foundation for further disenfranchisement and inequalities in the future of Tennessee.

Further Reading[edit | edit source]

For more information on the above topics, see the History of Tennessee: Further Reading.

Antebellum Tennessee (1796-1861)

Early Settlements[edit | edit source]

Early Memphis[edit | edit source]

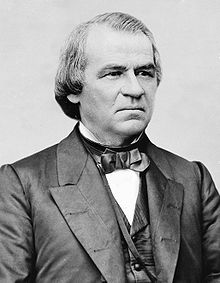

The area of Memphis had been populated long before becoming a part of the United States. Memphis was first populated by indigenous peoples many years prior to becoming part of the United States due in part to its geographical location. The land was found favorable because it is along the Mississippi River, while still being situated high enough to prevent flooding. The land would later be claimed by the Spanish, French, and British before coming into American hands. The US purchased the land in 1818 from the Chickasaw Indians. The town of Memphis was founded a year later by Andrew Jackson, James Winchester, and John Overton. Memphis was officially incorporated into the state of Tennessee in late 1826. Early Memphis found great success due to its prime location along the river, while the surrounding areas such as the Mississippi Delta were prime for cotton plantations, allowing the city to become a major player in the cotton market. This market at the time was mostly dominated by slave owners and because of that, Memphis became a large hub for the slave trade. By the 1850s, Memphis boasted the only east-west railroad in the south allowing it to grow to become the largest landlocked cotton market in North America at the time. This also caused Memphis to become a major target in the Civil war, which would come in the following years. The industry became so lucrative that when the debate over seceding to the union came, it was because while the town was definitely on the side of pro-slavery, they were hesitant to leave as there was a lot of money coming from the northern markets and leaving would cause a massive blow to business. The town of Memphis was designated by the government for white settlement after purchase. In the 1830s, the Indian Removal Act passed, forcing many people from their homes and to be relocated west of the Mississippi. Memphis became a hub for what would later be called the trail of tears, as many left from that point on their way to their new homes of designated Indian territory. Due to the slave-based nature of the economy in Memphis, African Americans made up a sizeable chunk of the population. This percentage grew from the town's founding until the war, when around one-quarter of the population were slaves. By the time the war began, the town had a population of about 55,000.

Founders Of Memphis[edit | edit source]

Founded in 1819 by the three men pictured, Memphis was named after the Egyptian city of the same name. The name was chosen due to the Egyptian city also being the capital and located on a prominent river.

-

Andrew Jackson

-

John Overton

-

James Winchester

Early Knoxville[edit | edit source]

Knoxville became part of the state of Tennessee in 1815 after much negotiation between surveyors and the regional Cherokee over boundaries. It served as the first capital of Tennessee up until 1817. Knoxville did not have a booming economy in it's early days, but rather was known as a "rough around the edges" hub for travelers to stop and rest as they made their way down the river or westward across the country. Hundreds of travelers passed through the city on a daily basis, prompting quick growth of local businesses. The geographical location of the town signaled a prosperous economic future as it was at the convergence of three rivers. Knoxville quickly became a sales hub for the local area as many came down from the surrounding mountains of the Appalachian to head into the town for imported goods. The town most prominently brought in cotton from the south in exchange for locally grown products. Much like Memphis, the town's population and business center experienced real growth once the railroad was built in the 1850s. Knoxville's growth had been hindered by the fact that it was relatively isolated due to the mountain ranges that blocked off the city from everyone else. It became very difficult to traverse by road and thus severely stunted the growth of the population for many years following its founding. Due to these issues, Knoxville legislators were some of the most enthusiastic when it came to building a rail line that connected them with the rest of the states. Unfortunately, before its eventual introduction in 1854, the city witnessed the financial failure of one line in the 1830s. This introduction put the expansion on a fast track as the population went on to more than double in the decade. The city went on to open multiple factories producing train cars among other things before the civil war began.

Early Nashville[edit | edit source]

Before becoming incorporated in 1806, the area was home to Fort Nashborough, a small stockade located in the middle of what would become Tennessee. The fort would become a cornerstone of the early city, which would quickly grow and flourish due to its prime positioning in relation to the rest of the state, as well as the Ohio River. The city thrived and continue to grow, quickly becoming the state's capital from 1812 to 1817. In 1817, Knoxville once again became the capital of Tennessee, however, Nashville would regain capital status in 1826, a title which it still holds today. In the late 1840s, when the cholera epidemic made its way to the interior states, Nashville found itself hit hard. Over 1849-1850, cholera ran rampant in the town. It is approximated that over the course of these two years, between 700-800 people lost their lives due to the epidemic. This was devastating due to the fact that the population of Nashville at the time was already under ten thousand. The most notable life claimed by the outbreak was that of James K. Polk, the acting president at the time. While he was not considered to have contracted cholera while in Nashville he did, however, succumb to it in Nashville in the summer of 1849. In the mid-1850s, the railroad was built through the city, further taking advantage of the prime location that it was founded on. This led to the further expansion and boom of the city with its perfect location. However, this prime location proved detrimental once the civil war came, causing it to be a focal point for the opposing sides.

Conflicts[edit | edit source]

Cherokee Wars[edit | edit source]

The Cherokee-American War, otherwise called the Chickamauga Wars, were a number of significant clashes and skirmishes between the Cherokee and other affiliated tribes and European settlers in the southern frontier of the United States, caused by an increase in European settlement in Cherokee lands, such as Tennessee. The conflict lasted through 1776-1795. The War split into two parts, the first part lasting from 1776-1783 and the second part lasting from 1783-1794. During the first part of the war, (Included the Revolutionary War) the Cherokee formed an ally with the British to fight against their American adversaries. The second part of the war consisted of the Cherokee location/settlement shifting to the West. As a result, The Cherokee served as a surrogate between New Spain and the United States of America.

The sacred home of the Cherokee Nation was, what is now, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, settled by the Cherokee in approximately 1000 A.D. after leaving from the New England states. Cherokee living was hunting, trading, growing their food and living in small, matriarchal communities. The first Europeans arrived in 1540, when explorer Hernando de Sota, of Spain, surveyed the Cherokee territory. When more European explorers and traders came to the North America, the Cherokee had settled and controlled much of the southeastern United States. In the late 1700’s, many, many settlers arrived from Europe ready for a life in the United States. The Cherokee fought with settlers but eventually withdrew to the Blue Ridge Mountains. The Tennessee Cherokee used a lot of the tools, weapons and methods brought by the settlers and these items affected their everyday life as they began to hunt animals for their pelts, not only for food, as they needed pelts to trade for goods. The more people arrived to settle on the Cherokee land, the more conflict arose. These battles against whites with better weapons, as well as new diseases brought over from Europe led to much Cherokee death. A conflict between British soldiers and the Overhill Cherokees at Fort Loudoun ended with British surrender on August 7, 1760. Captain Paul Demeré and some men were ambushed and the fort and the rest of the soldiers were taken prisoner. The Cherokee were the last native group to live in Tennessee. The fur trade changed the Cherokee way of life forever. The Cherokee became dependent on European goods and over hunted the region’s animals. The French and Indian War and the Seven Years' War led to even more fighting between the Cherokee and American settlers, as British and Spanish used the Cherokee to fight the Americans further their own ambitions. The Cherokee Nation heavily influenced the southern frontier including the state of Tennessee. The name Tennessee itself was named when British settlers arrived at a Cherokee village called Tanasi which means “winding-river” or “river of great bend” which is now referred to as the Little Tennessee River. The war was considered very irregular as it consisted of guerrilla tactics, periods of inactivity, and a range of small to larger battles. The Seven Years’ War (between French and Natives) also influenced further tension amongst the Cherokee and American settlers. Dragging Canoe, also known as The Savage Napoleon, was a Cherokee leader who led Cherokee warriors and other members from neighbouring Indian tribes during the war.

During the American Revolution, the Cherokee fought against the American settlers in their region, and also as allies of British against their American colonies. For example, Fort Watauga at Sycamore Shoals was attacked in 1776 by Dragging Canoe and his over 1,000 Cherokee warriors and nearly wiped out Fort Nashborough (which later became Nashville) the Battle of the Bluffs in April 1781. With The 1775 Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, also known as the Transylvania Purchase, the Cherokee sold Kentucky and Middle Tennessee to the American colonies. Dragging Canoe hated this Treaty and said the settlement of those lands would be “dark and bloody,”. At the end of the American Revolution, most Cherokee wanted peace with the United States. When the Treaty of Dewitt's Corner was signed in June 1776, Dragging Canoe and his warriors moved further down the Tennessee River to further white settlement from a better location. Since there were more loyalists in the south, British troops started to focus their war campaign south towards the end of 1778. The revolutionary phase or the Cherokee of War 1776 (first part of the war) consisted of the Cherokee fighting settlers and others that intruded their land. This phase started off with the Loyalists retreating back from Cherokee land as tensions began to rise rapidly. Known and feared Loyalists such as John Stuart (Superintendent of Indian Affairs) and Thomas Brown both flee to ensure their safety. Northern Tribes (Iroquois, Ottawa, etc.) were led by a British governor to delegate with southern Tribes (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee). This was done to encourage all the tribes to fight alongside the British against the Americans. Dragging Canoe accepted these terms by accepting ceremonial belts from the potential partnering tribes. Before fighting alongside the northern tribes, Dragging Canoe first initiated a small battle/raid in Kentucky. After the small raid in Kentucky, the first Cherokee campaigns commenced. War parties were sent to South and North Carolina. The Cherokee conquered land around the Blue Ridge, and the Catawba River. Following that, Cherokee and Loyalist (dressed like Cherokee) attacked a fort (named Lindsay Station) in South Carolina. There were no Cherokee casualties. Ultimately, there were multiple attacks on the American frontier. Forts and land were captured by the Cherokee, partnering tribes and the loyalists to ensure their power. The affected colonies were determined to respond back to recover their crippled frontier. Thousands of men were sent throughout the frontier, which included the areas of Little Tennessee, South Carolina, and Georgia. The Colonial Response resulted in numerous battles such as the Battle of Twelve Mile Creek, Ring Fight, Battle of Tugaloo, and the Battle of Tamassee. After a series of battles, a summit meeting, which included western tribes (Muscogee, Mohawk, Seneca, Etc.), was held in January 1783. The meeting was held in St. Augustine (capital of Eastern Florida), where Dragging Canoe, along with 1,000 Cherokees attended. The summit requested for a union with the Indians to oppose colonists and the American settlers. A couple of months after in Tuckabatchee, the Cherokee and other major/smaller tribes attended another council meeting. This meeting ended with a disagreement about the federation and the Treaty of Paris was written and signed. The treaty was signed in May, 1783 and was designed to create boundaries between the State of Georgia and the Cherokee. The Treaty of Paris was signed between the British and the United States which ended the American Revolution. After signing the treaty, Dragging Canoe partnered up with the Spanish as they had a lot of influence in the south. The Spanish and Dragging Canoe worked together to oppose the Americans. Smaller Indian bands such as the Chickasaw and Muscogee signed the Treaty of French lick in November 6, 1783 which was designed to prevent them from attacking/fighting/going to war, with the United States. During this time, the Lower Cherokee were also prevented to attack until more Americans settled in the frontier. Warfare broke out in the summer of 1776 in east Tennessee and later spread to along the Cumberland River in Middle Tennessee.

During the American Revolution, the Cherokee fought against the American settlers in their region, and also as allies of British against their American colonies. For example, Fort Watauga at Sycamore Shoals was attacked in 1776 by Dragging Canoe and his over 1,000 Cherokee warriors and nearly wiped out Fort Nashborough (which later became Nashville) the Battle of the Bluffs in April 1781. With The 1775 Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, also known as the Transylvania Purchase, the Cherokee sold Kentucky and Middle Tennessee to the American colonies. Dragging Canoe hated this Treaty and said the settlement of those lands would be “dark and bloody,”. At the end of the American Revolution, most Cherokee wanted peace with the United States. When the Treaty of Dewitt's Corner was signed in June 1776, Dragging Canoe and his warriors moved further down the Tennessee River to further white settlement from a better location. The climax of the Cherokee influence occurred from 1788-1792 which was during the Post-Revolutionary stage. From 1788-1789, the Cherokee-Franklin War occurred, which was the most violent war since the wars of 1776. In 1789, a council at Coweta, declared that Cherokee and Muskogee can no longer trust both the Spanish and Americans. Furthermore, the council wrote a letter to Great Britain to announce they were willing to be loyal to the king in return for his support. However, this plan never really fell through. Commencing this, this stage of the war consisted of a range of treaties and battles. There was a Prisoner exchange, Treaty of New York (1790), Bob Benge’s War, and the Battle of Wabash. Ultimately, these series of events led to the death of Dragging Canoe. In 1792, Dragging Canoe died from a possible heart attack after celebrating northern victory. A majority of the conflicts ended in November 1794 with the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse. The Northwest Indian War ended with the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. The Cherokee and other Indian tribes were forcibly removed from their lands when the Indian Removal Act in 1830 was passed into law. The Cherokee called this the Nunna daul Isunyi—"the Trail Where We Cried" or "Trail of Tears”. Most of West Tennessee remained Indian land until the Chickasaw Cession of 1818, when the Chickasaw ceded their land between the Tennessee River and the Mississippi River.

African American Slave Life on Plantations[edit | edit source]

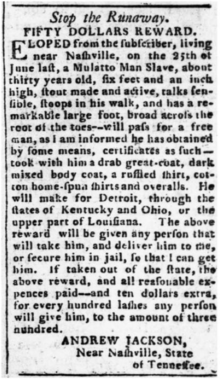

African American life on the plantations of Tennessee during the Antebellum period leading up to the civil war, represented the larger societal interactions between races in economics, politics, and culture. Ideals of white supremacy supported the oppression and forced labour of African American slaves within plantations. Divided across the landscape, plantations in the west were primarily of cotton export, while those in the middle-featured tobacco, livestock and wheat. Madison County is representative of Tennessee’s slaveholding and cotton producing southwestern sector. In 1860, two out of five white families, within the area, owned at least one slave. Anywhere from one, to fifteen, to one hundred slaves may be employed on a singular plantation, depending on the geography, and the requirements of the produce and planter. The Hermitage, a one thousand-acre plantation owned by former president Andrew Jackson, at its largest size, exploited the labor of one hundred and forty African American slaves.

Institutional Slavery in Tennessee[edit | edit source]

Slavery was prevalent in the Antebellum era in Tennessee, with there only being a population of 77,262 residents in the state, of which 10,613 were slaves by the year 1796. The legal status of each of these slaves were determined by the North Carolina Act of Cession which legally allowed slavery in the new statehood of Tennessee. By this time in the United States, governments had more control over slavery compared to the slave owners, which made committing any crimes against these slaves more difficult to do without consequence. This sometimes meant slaves were rewarded with “more freedom of action and movement than was allowed in the older states and regions of the lower south.” To say that these slaves and their families had it easier than others though, would be an overstatement, as the physical, mental, and emotional pain these families went through remained prevalent throughout slave history and afterwards. For young women who grew up as slaves, as explained by the Tennessee Tribute, "puberty marked the beginning of a lifetime of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse from masters and mistresses, and members of the planter family." Travelling as a slave was regulated by a system using passes which were supplied by their masters. "No slave, except a domestic servant, was supposed to leave his master's premises without a pass, explaining his cause of absence", Caleb P. Patterson noted in The Negroe in Tennessee. The rights slaves did have on these plantations included permission of one person to carry a gun for hunting during the cultivation for harvesting crops. However, if this person were caught hunting unlawfully, they were "whipped not exceeding 30 lashes." While slavery was still on the rise in the late eighteen to early nineteenth century, slaves could be purchased at about $300 each, and by the year 1832 that had risen to an average of about $800. However, in some counties including Davidson County, slaves were hired for as little as 15 dollars per year. In most circumstances, the prices of slaves would fluctuate with the rise of cotton culture as well as any changes to the country’s economic prosperity. The act of trading or selling slaves was often difficult, as it was illegal to do so between states from 1826 and 1855 and in 1823 self-hiring became illegal, which had the potential to land anyone caught doing so in trouble. It was much easier to hire slaves within Tennessee, as many slave-owners often “did not require the services of all their slaves at one time,” it was often that their neighbours would hire slaves from them for shorter periods of time. This was seen as very easy for all parties because cheap labor would be obtained by the hirer, and the owner was able to put one of his otherwise unused slaves to work for a profit.

Layout and Structure[edit | edit source]

Slavery in Tennessee followed a unique layout due to Tennessean geography. The Western section of the state was best suited to traditional agriculture development due to its placement on the banks of the Mississippi River. This portion of the state was dominated by white settlers from other U.S states, chiefly from Virginia. This focus on traditional agriculture meant that few large scale slave operations existed; large plantation style estates were deemed to be unprofitable in this region. While slavery did exist in Eastern Tennessee, it was usually limited to one or two slaves per owner. The center of the state was dominated by ranches and the raising of cattle, another style that did not lend itself to large amounts of slaves on one property. The Western portion of the state was dominated by large-scale cotton and tobacco plantations.

The layout of the average plantation was similar to that of a small village. Many buildings were constructed to meet the high demands. The buildings varied farm to farm, however often included a smokehouse, icehouse, hen house, schoolhouse, slave quarters, livestock housing, corn pen, cotton house, and food shelters. The master, or planter’s quarters, was generally referred to as the “big house”, due to its elaborate display of wealth and power. The multi-storeyed mansions, furnished with luxury, stood in stark contrast to the small accommodations provided for African Americans. On average, slave quarters were made up of sixteen-foot by sixteen-foot log cabins that were intended by planters to keep their slaves, literally and figuratively, in their place. The difference in condition between the “big house” and slave quarters, serves as a physical representation of oppression from master to slave, and became a means of establishing a social hierarchy on the plantation. The organization of slave housing was generally divided by job. Cooks and house servants lived near the master’s house, while field hands lived closer to the crops. Storage pits featured beneath the floors of the slave cabins do not correlate with earlier African architectural forms and are evidence of the influence of European culture on African Americans oppressed on plantations.

Work and Leisure[edit | edit source]

The lives of slaves on the plantation were dictated by the agricultural calendar and seasons of plowing, planting, hoeing, and harvesting. Throughout the year, and across multiple plantations, slave labor varied due to the demands of the farm crop and master. For example, a cotton plantation, requires the harvesting, ginning, and baling of the crop. Slaves were also employed in mines, fields, manufactories, shops, and houses. Under particularly savage authority, slaves often worked deep into the winter, sometimes as late as February. Winter duties included fixing ploughs, cutting wood, knocking down stalks of cotton and corn, and collecting manure. Children worked to carry dinner and collect water. Slaves who were too old to work in the fields, regularly labored as cooks, and in the spinning and weaving of cotton. Skilled slaves worked as carpenters, horse trainers, groomsmen, mill workers, and wood cutters. Slaves were forcibly worked by their masters to the maximum possible potential, often through horrific, and inhumane conditions. In their free time, slaves tended to their gardens which provided an important supplement to their meagre diets. Although slaves were constantly deprived of breaks, regularly scheduled rests often came on Sundays as slaves occasionally attended church with their masters. Christmas, however, was the best opportunity for leisure as work lightened, and masters often granted certain freedoms, such as congregation at local free black households. Throughout the year planters kept records that tracked the harvest progress of slaves sorted by name and yield. The tense slave-master relationship varied as slaves were subject to different forms of treatment across different plantations.

Punishment and Resistance[edit | edit source]

As a slave, the consequences for not fulfilling your master’s wishes were brutal, savage, and inhuman. Regardless of age, whippings and lashings were given as regular punishment for disobedience. Reports describe the flagellation of slaves younger than fifteen. They were often chased down on horseback and beaten, leaving them broken, bruised, and bloody. In cotton picking season, women who did not work fast enough were punished in the harshest manner. Despite the abuse, when unsupervised, slaves on the plantation, often executed forms of resistance and revolt. A common method of rebellion was to purposefully work below the required quota, and not fulfill particular demands arranged by the master. Slaves often, also engaged in thievery of livestock and food, as well as robberies on the “big house”. The most substantial form of defiance was escaping the plantation in search of freedom. Slaves who ran away, were tracked and hunted by slave patrols. Patrols served the purpose of controlling the black population within American and maintaining fear. Once caught, slaves were returned to bondage and punished.

Slaves Brought to Trial[edit | edit source]

The legal process for accused slaves was another topic throughout the Antebellum period which became very corrupt and involved many changes. In all trials involving slaves, the jury in court were made up of justices and freeholders, who were all slaveholders. In 1815, there were 3 justices and 9 freeholders who were "empowered to try slaves for all offences", and by 1819 the amount of freeholders were increased to 12. It wasn't until 1825 where the jury may have contained non-slaveholders, if the full 12 freeholders could not be reached. However, the verdicts these non-slaveholders gave were often deemed invalid if it was shown that these jurors divided the jury decision. In 1835 the legal procedures surrounding slaves were switched for the better when special courts specifically for slaves were abandoned. The right of appeal was established and "no slave was to be tried by a jury until an indictment had been found against him by a grand jury in the regular way." This made Tennessee one of the 5 states to grant slaves the right of appeal. Although this did change the legal process for tried slaves in a major way, the fight didn't end for African Americans as only 13 years later the right of appeal was given back to the slave masters. In 1858, only a few years before the civil war, a law was passed which allowed 5 'creditable' (usually white) people to "file an accusation of insurrection or conspiracy to kill against a slave" which then allowed the judge to give permission to the jury to try the slave for this offence without waiting to file a notice regularly with the court. The rights of African Americans in the legal system at this time were never fair or even existent, since when one law helped these people out in the slightest way, there were always freeholders in the judicial system to diminish whatever progress had taken place.

Religion, Spirituality, and Beliefs[edit | edit source]

Although subject to forced assimilation into European culture, African Americans were largely able to maintain a strong independent belief-system, culture, and spirituality throughout the plantations of Tennessee. Items archaeologically recovered at plantation sites presumed to serve spiritual and religious purposes include: smoothed stones, glass beads, charms in the shapes of human fists, quartz crystals, reshaped ceramic, and animal bones. Identical items are found at slave dwellings throughout the eastern United States, and Caribbean. Quartz crystals, in arrangements with black stone and glass beads, draw similarities to the Minkisi, or charms, of the Bakongo peoples of the Congo-Angolan region of Africa. They reflect a larger African worldview of life and death, and are evidence of a distinct American slave culture influenced by the origin of African American slaves in Africa. Tiny copper alloy “fist-charms,” were believed to grant luck and fertility, as well as protection from harm. Colored glass beads served a multitude of medicinal, religious, and decorative purposes and were sewn onto clothing to ward off evil. The church and Christianity were used as a method to assimilate African Americans to white values, ideals, and culture. There, African Americans were taught subservience, and obedience. The ability of slaves on the plantations of Tennessee to preserve their rich spiritual heritage is analogous to African American persistence across the United States in the face of oppression, racism, cruelty and injustice.

Fear from Outside Communities[edit | edit source]

Present all throughout this time period is the fear from the white people of these societies of the African American population in general, and more specifically that they would eventually rise up against them. While Tennessee was one of the more liberal of the southern states when it came to the freedom and emancipation of slaves, it is clear that there was always an ongoing attempt to keep the power in their favor. As liberal as their policy on emancipation was, it also ensured that once a slave was emancipated they were to be removed from the state, as well as prevent already free blacks from immigrating to the state. It was their belief that it was the duty of African Americans to either be serving a master or “they should be removed from those areas where they were sufficiently numerous to endanger white dominance.” In the antebellum south generally, slavery was considered to present “a social system and a civilization with a distinct class structure, political community, economy, and ideology,” that was subscribed to mainly by the white members of society. They were the group most affected by the strong anti-slavery feelings felt by many in Tennessee, especially slave owners considering that many laws were in place that they would have seen as against them. Some of these included the master paying for anything stolen or damaged by the slave, be it food or clothing due to not being adequately provided so; as well as beating or physically abusing a slave becoming an indictable offense.

Life of Free African Americans[edit | edit source]

There were still many restrictions that people of color had to live by, even if they were considered to be free. Because of the dominating presence of slavery in these kinds of communities, the presence of those that were walking free angered many, “because of their self-sufficiency and very desire to live as free people” as well as the fact that they were made to be valuable counterpoints to all of those that were pro-slavery, typically those that owned slaves themselves. In order to maintain their legal status free African Americans had many rules that they had to follow on a daily basis. One of which was that they would have to have documents with them at all times that detailed exactly who they were and proved their freedom. Others were that they were exempt from joining the military, however it is believed that some may have been able to vote under the new constitution of 1834 in which “free men who should be contempt witnesses against a white man in court of justice” were allowed to vote. Most of those considered free were in most cases trapped in an in-between stage, in which they were “neither bond nor free.”

Decline of Slavery in Tennessee[edit | edit source]

The number of slaves in the state would begin to decline in the period leading up to the American Civil War. This decline was due to a number of factors. The key cause of the decline of slaves in Tennessee was due to a trend towards the sale of slaves into the Deep South. When the African slave trade was ended, the demand for slaves in the United States would skyrocket, with large cotton and tobacco plantations in Louisiana, Alabama and Georgia in need of increased labor. This meant that Tennessean slave owners could gain large profits by selling their slaves at auction; many opted to do so due to their dwindling profits within the state.

Davy Crockett[edit | edit source]

Davy Crockett is America’s quintessential folk hero, he is known as the king of the wild frontier and has come to represent America’s self-described resilient and conquering spirit. He is best known for his exploits in the military, particularly his participation in the battle of the Alamo, which is also a staple of American folklore.

Personal Life[edit | edit source]

Davy Crockett’s life began in a way that was not unique to any other American during the period. Davy was born in what was, at the time, North Carolina, but is known now as Greene County, Tennessee, on August 17th, 1786. Davy grew up in a poor, indebted family, and by the age of 12 he was indentured to a man named Jacob Siler by his father in order to clear one of his father’s debts. By 1802 Davy had entered the employment of a man named John Canady, for whom he worked for four years until 1806 when he was married to Polly Finley, and settled on a plot of land near her family home. Crockett and Finley had three children together and lived in three separate houses; the third of which in Franklin county is where Polly Finley died in 1915. Crockett would remarry a woman named Elizabeth Patton later that same year, with whom he had three children.

Military Career[edit | edit source]

Crockett’s military career began in 1813 when he enlisted as a scout for the Creek War. This was in response to the Fort Mims massacre of the same year, which Tennessee militia general Andrew Jackson used as a rallying cry for the war. Crockett served in the Creek war until the end of 1813. He re-enlisted in the military in August of 1814, when Andrew Jackson, now of the US Army, asked for support from the Tennessee militia in driving British forces out of Spanish Florida as part of the War of 1812. Once again Crockett returned home from service at the end of the same year. In the War of 1812, and to a lesser extent the Creek Wars, Crockett did not see much of the main action. However, it is here where his legend as an American folk hero began to grow. During his time in the Creek Wars, Crockett preferred hunting to feed his fellow soldiers over killing Creek warriors, which made him well known within the militia. Him being a soldier in general during the period helped initiate the creation of his legend by participating in what are considered essential wars in the American mythos.

Political Career[edit | edit source]