Backgammon/Printable version

| This is the print version of Backgammon You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Backgammon

History

History[edit | edit source]

Backgammon is one of the oldest board games played today, and can be most clearly traced to the ancient game tabula, which appears in an epigram of Byzantine Emperor Zeno (AD 476–481).[1]

The ancient Egyptians played a game called senet, which resembled backgammon,[2] with moves controlled by the roll of dice. The Royal Game of Ur, played in ancient Mesopotamia, is a more likely ancestor of modern tables games. Recent excavations at the "Burnt City" in Iran showed that a similar game existed there around 3000 BC. The artifacts include two dice and 60 pieces, and the set is believed to be 100 to 200 years older than the sets found in Ur.[3]

The ancient Romans played a number of games with remarkable similarities to backgammon. Ludus duodecim scriptorum ("game of twelve lines") used a board with three rows of 12 points each, and the pieces were moved across all three rows according to the roll of dice. Not much specific text about the gameplay has survived.[4] Tabula, meaning "table" or "board", was similar to modern backgammon in that a board with 24 points was used, and the object of the game was to be the first to bear off all of one's checkers. Three dice were used instead of two, and opposing checkers moved in opposite directions.[1][5]

In the 11th century Shahnameh, the Persian poet Ferdowsi credits Burzoe with the invention of nard in the 6th century. He describes an encounter between Burzoe and a Raja visiting from India. The Raja introduces the game of chess, and Burzoe demonstrates nard, played with dice made from ivory and teak.[6]

The jeux de tables, predecessors of modern backgammon, first appeared in France during the 11th century and became a frequent pastime for gamblers. In 1254, Louis IX of France issued a decree prohibiting his court officials and subjects from playing the games.[7] While it is mostly known for its extensive discussion of chess, the Alfonso X manuscript Libro de los juegos, completed in 1283, describes rules for a number of dice and tables games.[8] By the 17th century, tables games had spread to Sweden. A wooden board and checkers were recovered from the wreck of the Regalskeppet Vasa among the belongings of the ship's officers.[9]

Edmund Hoyle published A Short Treatise on the Game of Backgammon in 1743; this book described the rules of the game and was bound together with a similar text on whist.[10] The game described by Hoyle is, in most respects, the same as the game played today.

In English, the word "backgammon" is most likely derived from "back" and Middle English "gamen", meaning "game" or "play". The earliest use documented by the Oxford English Dictionary was in 1650.[11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b Austin, Roland G. "Zeno's Game of τάβλη", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 54:2, 1934. pp 202-205.

- ↑ Hayes, William C. "Egyptian Tomb Reliefs of the Old Kingdom", The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series 4:7. March 1946. pp 170-178.

- ↑ "Iran's Burnt City Throws up World’s Oldest Backgammon." Persian Journal. December 4, 2004. Retrieved on August 5, 2006.

- ↑ Austin, Roland G. "Roman Board Games. I", Greece & Rome 4:10, October 1934. pp. 24-34.

- ↑ Austin, Roland G. "Roman Board Games. II", Greece & Rome 4:11, February 1935. pp 76-82.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Charles K. "Chessmen and Chess", The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series 1:9, May 1943. pp. 271-279

- ↑ Lillich, Meredith Parsons. "The Tric-Trac Window of Le Mans", The Art Bulletin 65:1, March 1983. pp. 23-33.

- ↑ Wollesen, Jens T. "Sub specie ludi...: Text and Images in Alfonso El Sabio's Libro de Acedrex, Dados e Tablas", Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 53:3, 1990. pp. 277-308.

- ↑ "Vasamuseet — The Swedish-Tables Association", The Vasa Museum. Retrieved on August 12, 2006.

- ↑ Allee, Sheila. "A Foregone Conclusion: Fore-Edge Books Are Unique Additions to Ransom Collection". Retrieved on August 8, 2006.

- ↑ "backgammon", The Oxford English Dictionary. Second Edition, 1989. Retrieved on August 5, 2006. (Subscription required)

Play

Rules[edit | edit source]

Backgammon is a game of moderate complexity but with deep strategic elements. It does not take long to learn to play, although obscure situations do arise which require careful interpretation of the rules. Because the playing time for each individual game is short, it is often played in matches, where, for example, victory is awarded to the player who first wins five points.

In short, a player tries to get all of his pieces past his opponent's pieces and then off the board. This is difficult because the pieces are scattered at first and may be blocked or captured by the opponent.

Setup[edit | edit source]

Each side of the board has a track of twelve adjacent spaces, called points, usually represented by long triangles of alternating (but meaningless) color. The tracks are imagined to be connected across the break in the middle and on just one edge of the board, making a continuous line (but not a circle) of twenty-four points. The points are numbered from 1 to 24, with checkers always moving from higher-numbered points to lower-numbered points. The two players move their checkers in opposite directions, so the 1-point for one player is noted as the 24-point for the other. Some recorded games, however, keep the numbering of the points constant from the perspective of one player. Each player begins with two checkers on his 24-point, three checkers on his 8-point, and five checkers each on his 13-point and his 6-point.[1] [2]

Points 1 to 6, where the player must attempt to move his pieces, are called the home board or inner board. A player may not bear off any checkers unless all of his checkers are in his home board. Points 7 to 12 are called the outer board, points thirteen to eighteen are the opponent's outer board, and points nineteen to twenty-four are the opponent's home board. The 7-point is often referred to as the bar point and the 13-point as the mid point.[1][2][3]

Movement[edit | edit source]

At the start of the game, each player rolls one die. Whoever rolls higher moves first, using the numbers on the already-rolled dice. In the case of a tie, the players roll again. The players then alternate turns, rolling two dice at the beginning of each turn after the first.[1][2][3]

After rolling the dice a player must, if possible, move checkers according to the number of points showing on each die. For example, if he rolls a 6 and a 3 (noted as "6-3") he must move one checker six points forward, and another one three points forward. The dice may be played in either order. The same checker may be moved twice as long as the two moves are distinct: six and then three, or three and then six, but not nine all at once.[1][2][3]

If a player has no legal moves after rolling the dice, because all of the points to which he might move are occupied by two or more enemy checkers, he forfeits his turn. However, a player must play both dice if it is possible. If he has a legal move for one die only, he must make that move and then forfeit the use of the other die. If he has a legal move for either die, but not both, he must play the higher number.[1][2][3]

If a player rolls two of the same number (doubles) he must play each die twice. For example, upon rolling a 5-5 he must play four checkers forward five spaces each. As before, a checker may be moved multiple times as long as the moves are distinct.[1][2][3]

A checker may land on any point occupied by no checkers or by friendly checkers. Also it may land on a point occupied by exactly one enemy checker (a lone piece is called a blot). In the latter case the blot has been hit, and is temporarily placed in the middle of the board on the bar, that is, the divider between the home boards and the outer boards. A checker may never land on a point occupied by two or more enemy checkers. Thus, no point is ever occupied by checkers from both players at the same time.[1][2][3]

Checkers on the bar re-enter the game through the opponent's home field. A roll of 2 allows the checker to enter on the 23-point, a roll of 3 on the 22-point, etc. A player with one or more checkers on the bar may not move any other checkers until all of the checkers on the bar have re-entered the opponent's home field.[1][2][3]

When all of a player's checkers are in his home board, he must bear off, removing the checkers from the board. A roll of 1 may be used to bear off a checker from the 1-point, a 2 from the 2-point, etc. A number may not be used to bear off checkers from a lower point unless there are no checkers on any higher points.[1][2][3] For example, a 4 may be used to bear off a checker from the 3-point only if there are no checkers on the 4-, 5-, or 6-point.

A checker borne off from a lower point than indicated on the die still counts as the full die. For instance, suppose a player has only one checker on his 2-point and two checkers on his 1-point. Then on rolling 1-2 he may move the checker from the 2-point to the 1-point (using the 1 rolled), and then bear off from the 1-point (using the 2 rolled). He is not required to maximize the use of his rolled 2 by bearing off from the 2-point.

If one player has not borne off any checkers by the time his opponent has borne off all fifteen, he has lost a gammon, which counts for double a normal loss (i.e., two games toward the match in a game with normal stakes). If a player has not borne off any checkers, and still has checkers on the bar, or in his opponent's home board by the time his opponent has borne off all fifteen, or both, he has lost a backgammon, which counts for triple a normal loss (i.e., three games toward the match in a game with normal stakes).[1][2][3] In some variants, a further distinction is made between pieces in the opponent's home board, counting as a triple loss, and pieces on the bar, for a quadruple loss.

Doubling cube[edit | edit source]

To speed up match play and to increase the intensity of play and the need for strategy, a doubling cube is usually used. A doubling cube is a 6 sided die that instead of the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 on it, has the numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 on it. If a player believes his position to be superior he may, before rolling the dice on his turn, double, i.e., demand that the game be played for twice the current stakes. The doubling cube is placed with the 2 side face up to show that the game's value has been doubled. His opponent must either accept the challenge or resign the game on the spot. Thereafter the right to redouble (double again) belongs exclusively to the player who last accepted a double. If this occurs, the cube is placed with the face of the next power of two showing.[1][2][3]

The game rarely is redoubled beyond four times the original stake, but there is no theoretical limit on the number of doubles. Even though 64 is the highest number depicted on the doubling cube, the stakes may rise to 128, 256, 512 and so on.

A common rule allows beavers, which is the right for a player to immediately redouble when offered the doubling cube while retaining the cube instead of giving it back up. The redouble must be called before the originally doubling player rolls the dice. In this way, the stakes of the game can rise dramatically.[2] A raccoon is sometimes pemitted as a response to a beaver. A player who accepts a beaver may offer a raccoon, redoubling again. Beavers and raccoons are commonly allowed when backgammon is played for money game by game and usually not allowed in matches.

The Jacoby rule allows gammons and backgammons to count for their respective double and triple points only if there has been at least one use of the doubling cube in the game. This encourages a player with a large lead in a game to double, and thus likely end the game, rather than see the game out to its conclusion in hopes of a gammon or backgammon. The Jacoby Rule is widely used in money play but is not used in match play.[2]

The Crawford rule makes match play much more equitable for the player in the lead. If a player is one point away from winning a match, his opponent has no reason not to double; after all, a win in the game by the player in the lead would cause him to win the match regardless of the doubled stakes, while a win by the opponent would benefit twice as much if the stakes are double. Thus there is no advantage towards winning the match to being one point shy of winning, if one's opponent is two points shy.[2] To remedy this situation, the Crawford rule requires that when a player becomes one single point short of winning the match, neither player may use the doubling cube for a single game, called the Crawford game. As soon as the Crawford game is over, normal use of the doubling cube resumes.[2] Not quite as universal as the Jacoby rule, the Crawford rule is widely used and generally assumed to be in effect for match play.

Sometimes automatic doubles are used, meaning that any re-rolls that players must make at the very start of a game (when each player rolls one die) have the side-effect of causing a double. Thus, a 3-3 roll, followed by a re-roll of 5-5, followed by a re-roll of 1-4 that begins the game in earnest will cause the game to be played from the start with 4-times normal stakes. The doubling cube stays in the middle, with both players having access to it. The Jacoby Rule is still in effect.[2] Again, automatic doubles are common in money games. but they are rarely, if ever, used in match play.

Sample game[edit | edit source]

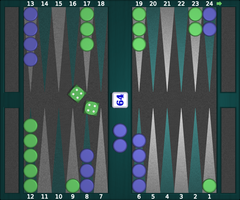

A few turns from the beginning of a sample game will illustrate the rules of movement. To start the game, blue rolls a 4 and green rolls a 1, so blue takes the first turn playing a 4-1. This is an unfavorable opening roll, arguably the worst possible, but blue uses it the best he can. He takes a checker from each of his heavy points by playing 13/9 6/5 (from the 13-point to the 9-point, and from the 6-point to the 5-point).

It is seldom useful to have five checkers on the same point, so blue starts to spread his checkers around. He is threatening to build a prime, that is, a blockade to prevent green's two trailing checkers from getting home. The disadvantage of blue's choice is that it is not very safe. It leaves two blots which green might hit. Some experts prefer the less aggressive but safer move of 24/23 13/9.

Green rolls a 4-4. This is a fortunate roll. Not only can he hit both of blue's blots with 1/5*/9* (from the 1-point to the 5-point, hitting blue, and from the 5-point to the 9-point, hitting blue again), he also has two more 4s to play. He may, for example play 19/23(2), moving two checkers from his 6-point to the 2-point. This leaves blue with two checkers on the bar, trying to re-enter against green's home board, which has two points blocked by green.

Green was wise to hit twice, because it disrupts blue's efforts to build a prime, and it puts blue considerably behind in the race. Those two checkers must come all the way around the board before blue can begin to bear off.

In contrast, green's decision to make the 2-point was strategically dubious. Though it may prevent blue from entering with both checkers, and there is some chance green will be able to build a strong home board before blue gets organized, increasing the chances of winning a gammon, the disadvantage is that green will now find it difficult to build a prime. If blue manages to make an advanced anchor, i.e., get two of his back checkers on green's 3-, 4-, or especially the 5- point, then green's blocking game is damaged.

Green would be in better shape had he played 12/16(2), keeping open the option to block or attack depending on blue's next roll, or taking the 4-point with 17/21(2). The latter more aggressive play has roughly a 3% better chance of winning a gammon, but loses almost 1% more often according to computer analysis.[4] This is interesting as it highlights another aspect of backgammon strategy, the optimal move depends on the current standings: if green is one point from winning the match and in no need of a gammon, he should play safe with 12/16(2), otherwise green should try for the gammon and play the aggressive 17/21(2).

The game continues and blue rolls 5-2. The only legal move is bar/20. The two cannot be played from the bar because green owns his 2-point, and until blue has played all his checkers off the bar, he cannot play anywhere else. Therefore the 2 is forfeited and blue's turn is over.

Green got what he wanted, in that blue was not able to enter both checkers, but the fight is far from over. Green must hit the blot on his next roll, or else blue has a 50% chance to cover his blot and take a fairly strong position. Even if green does hit, blue has many rolls to hit back. A war for green's 5-point will shape the character of the game in the near future.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Robertie, Bill. Backgammon for Winners, Third Edition. 2002.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Keith, Tom. Backgammon Galore. "Backgammon Rules". 2006. Retrieved on August 5, 2006.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Hoyle's Rules of Games, Eighty-second printing. 1983

- ↑ Article on replies to 13/9, 6/5 at Backgammon Galore

Openings

The first moves of a backgammon game are the opening moves, collectively referred to as the opening, and studied in the backgammon opening theory. Compared to the widely studied opening theory in chess, the backgammon opening theory is not developed in as much detail. The reason for this is that following the first move, there are 21 dice roll outcomes per subsequent move, combined with many alternative plays for each outcome, making the tree of possible positions in backgammon expand much more rapidly than in chess.

Despite the complications posed by this rapid branching of possibilities, over the course of many years, a consensus did develop amongst backgammon experts on what is the preferred opening move for each given roll. Following the emergence of self-trained backgammon-playing neural networks, the insights on what are the best opening moves have changed in some unexpected ways.

Preferred opening moves[edit | edit source]

The table below summarises the most commonly preferred moves, for each of the 15 possible opening rolls, as selected by detailed computer simulations, referred to as "rollouts".[1][2] There are no opening moves consisting of doubles, because at the start of the game, each player rolls one die. Whoever rolls higher moves first, using the numbers on the already-rolled dice. In the case of a tie, the players roll again. In cases where no preferred play but only two or more alternative plays are given, these appear to be of equivalent strength within the statistical uncertainties of the simulations and no play could be singled out that is clearly superior.

The moves are captured in standard backgammon notation. For instance, 8/5 denotes the move of a piece from the 8-point to the 5-point.

| Roll | Preferred play | Common alternatives | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-1 | — | 13/11-24/23 | 13/11-6/5 | — |

| 3-1 | 8/5-6/5 | — | — | — |

| 4-1 | 13/9-24/23 | — | — | — |

| 5-1 | 13/8-24/23 | 13/8-6/5 | — | — |

| 6-1 | 13/7-8/7 | — | — | — |

| 3-2 | 13/11-24/21 | 13/10-13/11 | — | — |

| 4-2 | 8/4-6/4 | — | — | — |

| 5-2 | 13/8-24/22 | 13/8 13/11 | — | — |

| 6-2 | 13/11-24/18 | — | — | — |

| 4-3 | — | 13/10-13/9 | 13/10-24/20 | 13/9-24/21 |

| 5-3 | 8/3-6/3 | — | — | — |

| 6-3 | 24/18-13/10 | 24/15 | — | — |

| 5-4 | 13/8-24/20 | 13/8-13/9 | — | — |

| 6-4 | — | 8/2-6/2 | 24/14 | 24/18-13/9 |

| 6-5 | 24/13 | — | — | — |

The general message that emerges from the above table can be summarised as follows: unless one can make a point, and with the exception of the running move 24/13 (the lover's leap), a successful play is the combination of splitting the 24-point and moving a checker from the 13-point. The latter move should be as small as possible (resulting in a builder close to the 13-point), unless the stack at the 8-point can be reached (resulting in a balancing of the distribution between the 13-point and the 8-point).

The above opening moves which emerged from computer analysis demonstrate that a number of opening moves that were unquestioned for many decades are now considered suboptimal. One example is the move 13/11-13/8 on the roll 5-2. Although not a bad move, the alternative choice preferred by the analyses, 24/22-13/8, is now generally agreed upon to be optimal. In other cases, computer analysis has resulted in alternative strategies that were not seriously considered in the past. For instance, the opening move 8/2-6/2 for a roll of 6-4 was in the past greeted with disdain from experts, but turns out to be on average as effective as the usual plays (24/14 and 24/18-13/9).

Influencing factors[edit | edit source]

The consensus on opening moves is generally extended only to money play, meaning that these plays optimise the expected payout. However, a context different from money play can influence the choice of opening move and may very well tip the balance towards a play that is seen to be slightly inferior. Towards the end of a match play, one such important factor can be the state of the match.[3]

In practice, an even more important influencing factor is the preferred style of the player. A player might have a strong preference for one out of a number of alternative opening plays that are on average as effective, because the character of the move (passive or aggressive) better suits his or her playing style.[4][5][6][7]

References[edit | edit source]

Chouette

Brief Overview[edit | edit source]

The Backgammon Chouette is a social, multi-player form of backgammon and was mostly played socially when you would have a number of players conversing and playing against each other on the same table. Now days with the broad reach of the internet this form of backgammon can be played across different countries and various platforms. It can be a tremendous amount of fun, with lots of cube turns, players taking different points of view, getting to rotate and play as a team-mate of another player one game and against him the next. However, if it’s not done right, especially online, it can get boring quickly. This page will give you an outline of what a chouette is and how to play.

Basic Terms and Rules of a Chouette[edit | edit source]

One player – the “box” – plays against a team. One member of the team is the “Captain.” This all takes place on one board. The Captain has final say over all checker plays, although he can ask his team-mates for help in some situations. However, each player has his own doubling cube. He can double regardless of what his team-mates do, and he can take or drop if doubled on his own. A chouette is played just like a money game. There is no “match score” – you play one game, win or lose points, then go on to the next game. Positions change every game. In general, if the box wins, he stays as the box; if the Captain wins he becomes the box. Whether the Captain wins or loses, the next player in line becomes the Captain.

The scoring is just points won or lost. Each player has a running score, of plus or minus a certain number of points, or even. If you were playing for money, you would multiply this by the stakes, and that’s how many dollars ahead or behind you would be. Naturally, the sum of all the scores is always zero. Online chouettes can be somewhat awkward to run. There is no special software for chouettes. What is required is someone to run the chouette who understands a chouette, whom I call a monitor. The monitor keeps track of the position of all cubes, and tallies the running score. When a chouette gets large, it gets to be a lot of work.

Listed below is everyone’s responsibilities. From experience you should know that if everyone doesn’t follow these, it can really ruin things for everyone. A chouette can be an awful lot of fun. For the team, there is the opportunity to gang up on one helpless victim (the box), to consult on checker plays, to show how much smarter you are than the others by, say, dropping a double and losing one point when everyone else goes on to lose a doubled gammon – or by taking and winning two points when most of your teammates dropped and lost one. There is the excitement of being the box and winning or losing 5 or 10 or 20 points at a time.

Responsibilities When Playing a Chouette[edit | edit source]

When you are the Captain[edit | edit source]

- Turn on Board Notation so that you can understand the comments your team is making.

- If you want advice on a move, type the move in the chat box at the bottom of the screen before moving. You do not have to ask for advice, or to follow it. But it will be very frustrating to your teammates if you don’t ask their advice and then make foolish moves. It is generally considered good practice that, if you are a relatively weak player, to ask advice from the strong players, and if you are the strongest player on the team to just move. The bottom line is that your teammates will forgive you anything if you win, but if you lose and they think you did so foolishly, you won’t become very popular! Remember too that everyone else wants to be involved in the game. If you just keep moving without ever asking for advice, even on close plays, you’re taking your teammates out of the game.

- When you are in a position where anyone on the team might even be thinking of doubling, wait just a couple seconds before rolling. Give them the chance to say “double.” If anyone doubles, make sure to wait until the box has decided on all the cubes. But also, don’t wait forever to roll. If there has been any cube action, give the monitor a minute to record the results. Remember, he’s got a lot of paperwork to keep track of!

- Never use the “double” button on the board. If you want to double, say “double.” It will be very frustrating if the box reflexively drops and the game ends.

- A special situation arises if you drop but someone else on the team takes. Now, you are no longer allowed to participate in the game. In a real-life chouette, you would leave your seat and the person next in line to be Captain would take your place.

When you are the Box[edit | edit source]

- If you are doubled by one or more players, wait until everyone has had a chance to double. You might ask “anyone else?” You do not have to decide to take or drop until everyone has doubled who wants to. If you’re going to drop, then of course everyone will suddenly want to double!

- If you double, wait for everyone to decide to take or drop before rolling, and give the monitor time to record the results.

When you are the Team[edit | edit source]

- Pay Attention. It’s easy to lose interest in the game if you’re not an active participant, but you are very much a part of the game. One of the most frustrating things is when the box says “Double all” and one or two players on the team don’t respond and you’re waiting.

- Know the position of your cube. If you have doubled and the box has taken, don’t say “double.” You can’t double, and it will only slow the game down if the monitor has to tell you that you have already given your cube. (Of course, if you doubled to 2 and the box has redoubled to 4, you can now double to 8!) Likewise, if you doubled and the box dropped, you’ve already won this game. You’re out, you can’t win the same game twice!

For All Chouette Players[edit | edit source]

- Take the game seriously. If a player always doubles at the first opportunity, takes every double, and immediately redoubles. That kind of play takes away from the game, because this is supposed to be fun, but it’s supposed to be a test of skill. Pretend you’re playing for $10 a point! If that were the case, you’d play your best; you’d certainly pay attention even when you’re on the team. And if you were Captain and had money on the line, you’d try to get the better players to help you win. If you pretend you’re playing for real money, you’ll find you have more fun!

- Be patient. A real-life chouette goes almost as fast as a regular game, and when it slows down it's because people are discussing (or arguing!) over checker plays, which is part of the fun. Online, because the software doesn’t support chouettes, it can slow down a little. Try to be a little patient and keep focused on the game.

- If you have to leave, leave. There’s no requirement that you stay in a chouette for any particular period of time. If you’re losing interest, then just say that you’re leaving and leave. It’s best if you stay to the end of the current game, though.

Rules for Chouettes[edit | edit source]

- Jacoby Rule, backgammon beavers but no backgammon raccoons. explanations to these terms can be found in the glossary.

- Players on the team can consult only after their cube has been turned. This means that the Captain is free to play the opening in peace, while getting help once the game has advanced.

- If any player drops, the Captain may buy his cube. What that means is that the player who drops pays the Captain the undoubled value of the cube, rather than the box. The Captain is now playing with two (or three or four or five) cubes against the box.

- If all players but one drop, that player must either drop or he must buy all the other cubes. This prevents one player from holding up the game. However, in this case it works a little differently. The box still gets the point from all the cubes. However, each player on the team pays the remaining player one additional point, and they now join the box. If you are doubled and drop, you are saying that you would rather pay one point to get out of the game than play on with a 2-cube. So if someone said “I think it’s better to play on with a 2-cube than drop” you should be willing to say “OK, I will pay you one point to take that inferior side of the board and play it with a 2-cube.” This way, if one player wants to play on, everyone is still involved in the game.

- Settlements are allowed. Lets look at a very simple example. Suppose you are in a last-roll position. The cube is at 4, and you have one checker on your 5-point and one on your one-point; your opponent has one checker on his one-point. You have 23 rolls that win the game and 13 that lose. On average in 36 games you will win 92 points and lose 52, for a net average of (92-52) / 36, or about 1.1 points. You might say “I’ll take one point.” Anyone who wants can now pay you one point and the game ends for them. Settlements can be proposed by either side at any time.

Further Information[edit | edit source]

Glossary

A[edit | edit source]

- Acey-deucey (or Acey-deucy)

- A variant of backgammon in which the roll of 1 and 2 gives the player extra turns.

- Anchor

- A point occupied in the home board by two or more of opponent's checkers.

B[edit | edit source]

- Backgammon

- A game in which one player bears off all of his checkers while his opponent still has one or more checkers on the bar or in the winner's home board, counting for triple a normal game.

- Bar

- The area where blots are placed after being hit, usually, a raised divider between the home boards and outer boards.

- Bar point

- Either of the two points in the outer board adjacent to the bar; the 7-point or the 18-point.

- Bear off

- To remove a checker from the home board by rolling a number that equals or exceeds the point on which the checker resides.

- Block

- A point occupied by two or more checkers on the home board or the outer board.

- Blot

- A single checker vulnerable to being hit.

C[edit | edit source]

- Checker

- One of the 15 playing pieces allotted to each player.

- Cubeless Equity

- The value of a position ignoring the use of the doubling cube. This is a value between -3 and +3 that takes into account the probabilities of either side winning a single game, winning a double game or winning a triple game. If at a given point in the game neither party can make a gammon, the cubeless equity of a player simply is the probability of him/her winning the game, minus the probability of the opponent winning the game.

D[edit | edit source]

- Deep Anchor

- An anchor on the opponent's one-point or two-point.

- Doubles

- A dice roll in which both values are identical, e.g. 1-1 or 6-6.

E[edit | edit source]

- End Game

- The phase of a game which starts when one of the players begins to bear off.

F[edit | edit source]

- Full prime

- A prime of six consecutive points that completely blocks the opponent from moving checkers in front of the prime to behind the prime.

G[edit | edit source]

- Gammon

- A game in which one player removes all his checkers before his opponent can remove any, and counted as a double win.

H[edit | edit source]

- Home board

- The portion of the board containing points 1-6. The checkers need to move here before they can be borne off. It is also the part of the board where the opponent's checkers are re-entered from the bar.

I[edit | edit source]

- Inner board

- Home board.

M[edit | edit source]

- Match

- A series of games of backgammon, played until one participant reaches a predetermined score.

- Mid point

- Either of the two points furthest from the bar; the 12-point or the 13-point.

N[edit | edit source]

- Normalized Match Score

- A match score expressed in terms of the number of points needed by both sides to win the match. For instance, '2-away/4-away' (or: -2/-4) could indicate the state of seven-point match in which one party has gained five points and the other side three points.

- Notation

- In backgammon the common way of describing the movement of checkers involves numbering the points around the board from 24 to 1 such that the numbers diminish when the checkers move towards the home board. This implies that a reverse numbering applies when the opponent is on roll (with the 24-point now referred to as the 1-point, etc.). A move of a single checker is indicated by the start and the end number separated by a slash. If a move results in a checker being hit, this is indicated by adding an asterisk to the number on which a checker was hit.

O[edit | edit source]

- Open point

- A point a player can in principle move his checkers to. I.e. a point that is not occupied by more than one opposing checker.

P[edit | edit source]

- Pip

- One of the markings on the face of a die, corresponding to a movement of one point.

- Point

- One of the twenty-four narrow triangles on the backgammon board where the players' checkers sit, or the value of a single game of backgammon before accounting for the doubling cube, or a gammon or backgammon.

- Prime

- Several consecutive points held by a player.

S[edit | edit source]