Art History/19th Century

Impressionism[edit | edit source]

Photography in the nineteenth century both challenged painters to be true to nature and encouraged them to exploit aspects of the painting medium, like color, that photography lacked. This divergence away from photographic realism appears in the work of a group of artists who from 1874 to 1886 exhibited together, independently of the Salon. The leaders of the independent movement were Claude Monet, August Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and Mary Cassatt. They became known as Impressionists because a newspaper critic thought they were painting mere sketches or impressions. The Impressionists, however, considered their works finished. Many Impressionists painted pleasant scenes of middle class urban life, extolling the leisure time that the industrial revolution had won for middle class society. In Renoir's luminous painting Luncheon of the Boating Party, for example, young men and women eat, drink, talk, and flirt with a joy for life that is reflected in sparkling colors. The sun filtered through the orange striped awning colors everything and everyone in the party with its warm light. The diners' glances cut across a balanced and integrated composition that reproduces a very delightful scene of modem middle class life.

Since they were realists, followers of Courbet and Manet, the Impressionists set out to be "true to nature," a phrase that became their rallying cries. When Renoir and Monet went out into the countryside in search of subjects to paint, they carried their oil colors, canvas, and brushes with them so that they could stand right on the spot and record what they saw at that time. In contrast, most earlier landscape painters worked in their studio from sketches they had made outdoors. The more an Impressionist like Monet looked, the more she or he saw. Sometimes Monet came back to the same spot at different times of day or at a different time of year to paint the same scene. In 1892 he rented a room opposite the Cathedral of Rouen in order to paint its facade over and over again. He never copied himself because the light and color always changed with the passage of time, and the variations made each painting a new creation. The differences are obvious when we compare the painting of Rouen Cathedral that is now in Switzerland with the one that is now in Washington, D.C. Realism meant to an Impressionist that the painter ought to record the most subtle sensations of reflected light. In capturing a specific kind of light, this style conveys the notion of a specific and fleeting moment of time. Impressionist painters like Monet and Renoir recorded each sensation of light with a touch of paint in a little stroke like a comma. The public back then was upset that Impressionist paintings looked like a sketch and did not have the polish and finish that more fashionable paintings had. But applying the paint in tiny strokes allowed Monet, Renoir, or Cassatt to display color sensations openly, to keep the colors unmixed and intense, and to let the viewer's eye mix the colors. The bright colors and the active participation of the viewer approximated the experience of the scintillation of natural sunlight. The Impressionists remained realists in the sense that they remained true to their sensations of the object, although they ignored many of the old conventions for representing the object "out there." But truthfulness for the Impressionists lay in their personal and subjective sensations not in the "exact" reproduction of an object for its own sake. The objectivity of things existing outside and beyond the artist no longer mattered as much as it once did. The significance of "outside" objects became irrelevant. Concern for representing an object faded, while concern for representing the subjective grew. The focus on subjectivity intensified because artists became more concerned with the independent expression of the individual. Reality became what the individual saw. With Impressionism, the meaning of realism was transformed into subjective realism, and the subjectivity of modem art was born.

Artists[edit | edit source]

- Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875)

- Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878)

- Gustave Courbet (1819-1877)

- Eugene Boudin (1824-1898)

- #Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)

- Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)

- Edouard Manet (1832-1883)

- Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

- Claude Monet (1840-1926)

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

- Frederic Bazille (1841-1870)

- Berthe Morisot (1841-1895)

- Mary Cassatt (1844-1926)

- Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894)

- Paul Gauguin (1848-1903)

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)[edit | edit source]

Born July 10, 1830 in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. His father, a Portuguese Jew, ran a general store. Although Pissarro attended school in Paris and demonstrated an exceptional talent for drawing, he returned to St. Thomas in 1847 to work in the family business. During the ensuing years his interest in art persisted, and in 1855 his parents finally yielded to his ambition to become a painter.

Pissarro reached Paris in time to see the important World's Fair of 1855. He was particularly impressed by the landscapes of Camille Corot and other members of the Barbizon group, who had taken the first steps toward working directly from nature, and by the ambitious and forthright realism of Gustave Courbet, although his own work increasingly gravitated toward landscape rather than figurative subjects.

During the next 10 years, Pissarro received some academic training at the École des Beaux-Arts, but he spent most of his time at the Académie Suisse, where free classes were offered. This was an important gathering place for those artists whose ambitions and sensibilities lay outside the teaching of the official schools, for it offered greater opportunity to discuss and develop personal ideas about painting and art in general. In this setting Pissarro became friends with Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Paul Cézanne, who were seeking alternatives to the established methods of painting. Pissarro's works at this time were occasionally, though by no means consistently, accepted at the annual Salons. More importantly, however, he received critical backing and encouragement from the journalist and critic Émile Zola.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-7, Pissarro and Monet went to London, where they were impressed by the landscape paintings of John Constable and J.M.W. Turner. By this time Pissarro and Monet had begun to work directly from nature and to develop the unique style that would later be called Impressionism. In their pursuit of this new and revolutionary direction, the lessons of the earlier English landscapists provided crucial and much-needed support, particularly in terms of the loose handling of paint, the abstractness, and the strong response to nature that characterized their own paintings. When Pissarro returned to his home at Louveciennes near Paris, he found that the Prussians had destroyed nearly all of his paintings.

By the early 1870s, the work of Pissarro and his colleagues had been rejected by the Salon, France's official state-run art show, on repeated occasions. In 1874, they held their own exhibition, a show of "independent" artists, which included the work of Pissarro, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Edgar Degas, and Berthe Morisot. This was the first Impressionist exhibition (the term "Impressionist," originally used derisively, was actually coined by a newspaper critic). There were seven similar exhibitions from 1874-86, and Pissarro was the only artist who participated in all eight. This fact is important because it reveals something about Pissarro's relation to Impressionism generally: he was the patriarch and teacher of the movement, constantly advising younger artists, introducing them to one another, and encouraging them to join the revolutionary trend that he helped to originate. In 1892, a large retrospective of Pissarro's work finally brought him the international recognition he deserved. Characteristic paintings are Path through the Fields (1879), Landscape, Eragny (1895), and Place du Théâtre Français (1898). He died in Paris on November 12, 1903. Although his work was generally less innovative than that of his major contemporaries, his contributions as an artist should not be underestimated in the development of the Impressionist painting style.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)[edit | edit source]

Born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas on July 19, 1834, in Paris, France. A member of an upper-class family (his father was a banker), Degas was originally intended to practice law, which he studied for a time after finishing secondary school. In 1855, however, he enrolled at the famous École des Beaux-Arts, or School of Fine Arts, in Paris, where he studied under Louis Lamothe, a pupil of the classical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. In order to supplement his art studies, Degas traveled extensively, including trips to Naples, Florence, and Rome (where he lived for three years), in order to observe and copy the works of such Renaissance masters as Sandro Botticelli, Andrea Mantegna, and Nicolas Poussin. From his early classical education, Degas learned a good deal about drawing figures, a skill he used to complete some impressive family portraits before 1860, notably The Belleli Family (1859). In 1861, Degas returned to Paris, where he executed several "history paintings," or works with historical or Biblical themes, which were then the most sought-after paintings by serious art patrons and particularly the prestigious state-run art show, the Salon, held each year in Paris. He also began copying works by the Old Masters from the Louvre, which he would continue doing for many years. With his historical paintings (including 1861's Daughter of Jephthah, based on an incident from the Old Testament) and his finely-wrought portraits of friends, family members, and clients, the young Degas quickly established a reputation among French art circles and never suffered from the financial problems that plagued many of his contemporaries.

Soon, however, Degas began to shift his focus from historical painting to depictions of life in contemporary Paris. By 1862, he had begun painting various scenes from the racecourse, including studies of the horses, their mounts, and the fashionable spectators. Degas' style after the early 1860s was influenced by the budding Impressionist movement, including his friendship with Édouard Manet, as well as his introduction to Japanese graphic art, with its striking representation of figures. Along with his work painting scenes from the racetrack, Degas began concentrating on portraits of groups, most notably of female ballet dancers, who became Degas' most famous subjects. Degas served in the artillery division of the French National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. Upon his return, he worked on even more ambitious studies of groups, often in motion, in both indoor and outdoor settings. In October 1872, Degas visited the United States for five months, spending time in New Orleans, Louisiana, where some members of his family were in the cotton business. From this experience came his famous painting New Orleans Cotton Office (1873).

Many of Degas' paintings featured the artist's experiments with unorthodox visual angles and asymmetrical perspectives, somewhat like a photographer's treatment of a subject. Examples of this style are A Carriage at the Races (1872), which features a human figure who is almost cut in half by the edge of the canvas, and Ballet Rehearsal (1876), a group portrait of ballerinas that appears almost cropped at the edges. From 1873 to 1883, Degas produced many of his most famous works, both paintings and pastels, of his favorite subjects, including the ballet, the racecourse, the music hall, and café society. Though he never suffered from lack of money or interest in his work, Degas stopped exhibiting at the Salon in 1874, and thereafter displayed most of his works alongside those of the other Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro. His strong focus on draftsmanship, portraiture, and composition distanced him from the rest of the artists identified as Impressionists.

Sometime in the 1870s, Degas began to suffer a loss of vision, which limited his ability to work. He began increasingly to work as a sculptor, producing bronze statues of horses and ballet dancers, among other subjects. A number of his sculptures, including Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1880-81), were figures dressed in real costumes, and many of them captured the moment of transition between one position to another, giving the statues a real sense of immediacy and motion. As Degas' eyesight grew worse, he became an increasingly reclusive and eccentric figure. In the last years of his life, he was almost totally blind. Edgar Degas died on September 27, 1917, in Paris, leaving behind in his studio an important collection of drawings and paintings by his contemporaries as well as a number of statues crafted in wax and metal, which were cast in bronze after his death.

Claude Monet (1840-1926)[edit | edit source]

Born November 14, 1840, in Paris, France. Claude Monet was a seminal figure in the evolution of Impressionism, a pivotal style in the development of modern art. In 1845 his family moved to Le Havre, and by the time he was 15, Monet had developed a local reputation as a caricaturist. Through an exhibition of his caricatures in 1858, Monet met Eugène Boudin, a landscape painter who exerted a profound influence on the young artist. Boudin introduced him to outdoor painting, an activity that he entered reluctantly but which soon became the basis for his life's work. By 1859 Monet was determined to pursue an artistic career. He visited Paris and was impressed by the paintings of Eugène Delacroix, Charles Daubigny, and Camille Corot. Against his parents' wishes, Monet decided to stay in Paris. He worked at the free Académie Suisse, where he met Camille Pissarro, and he frequented the Brasserie des Martyrs, a gathering place for Gustave Courbet and other realists who constituted the vanguard of French painting in the 1850s. Formative Period

Monet's studies were interrupted by military service in Algeria from 1860 to 1862. The remainder of the decade witnessed constant experimentation, travel, and the formation of many important artistic friendships. In 1862, he entered the studio of Charles Gleyre in Paris and met Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille. During 1863 and 1864, he periodically worked in the forest at Fontainebleau with the Barbizon artists Théodore Rousseau, Jean François Millet, and Daubigny, as well as with Corot. In Paris in 1869, he frequented the Café Guerbois, where he met Édouard Manet. At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Monet traveled to London, where he met the adventurous and sympathetic dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. The following year Monet and his wife, Camille, whom he had married in 1870, settled at Argenteuil, which became a semi-permanent home (he continued to travel throughout his life) for the next six years. Monet's constant movements during this period were directly related to his artistic ambitions. The phenomena of natural light, atmosphere, and color captivated his imagination, and he committed himself to an increasingly accurate recording of their enthralling variety. He consciously sought that variety and gradually developed a remarkable sensitivity for the subtle particulars of each landscape he encountered. Paul Cézanne is reported to have said, "Monet is the most prodigious eye since there have been painters." Relatively few of Monet's canvases from the 1860s have survived. Throughout the decade, and during the 1870s as well, he suffered from extreme financial hardship and frequently destroyed his own paintings rather than have them seized by creditors. A striking example of his early style is Terrace at Sainte-Adresse (1867). The painting contains a shimmering array of bright, natural colors, eschewing completely the somber browns and blacks of the earlier landscape tradition.

Monet and Impressionism[edit | edit source]

As William Seitz wrote in 1960, "The landscapes Monet painted at Argenteuil between 1872 and 1877 are his best-known, most popular works, and it was during these years that Impressionism most closely approached a group style. Here, often working beside Renoir, Sisley, Caillebotte, or Manet, he painted the sparkling impressions of French river life that so delight us today." During these same years, Monet exhibited regularly in the Impressionist group shows, the first of which took place in 1874. On that occasion his painting Impression: Sunrise (1872) inspired a hostile newspaper critic to call all the artists "Impressionists," and the designation has persisted to the present day.

Monet's paintings from the 1870s reveal the major tenets of the Impressionist vision. Along with Impression: Sunrise, Red Boats at Argenteuil (1875) is an outstanding example of the new style. In these paintings, Impressionism is essentially an illusionist style, albeit one that looks radically different from the landscapes of the Old Masters. The difference resides primarily in the chromatic vibrancy of Monet's canvases. Working directly from nature, he and the other Impressionists discovered that even the darkest shadows and the gloomiest days contain an infinite variety of colors. To capture the fleeting effects of light and color, however, Monet gradually learned that he had to paint quickly and to employ short brushstrokes loaded with individualized colors. This technique resulted in canvases that were charged with painterly activity; in effect, they denied the even blending of colors and the smooth, enameled surfaces to which earlier painting had persistently subscribed.

Yet, in spite of these differences, the new style was illusionistically intended; only the interpretation of what illusionism consisted of had changed. For traditional landscape artists, illusionism was conditioned first of all by the mind: that is, painters tended to depict the individual phenomena of the natural world-leaves, branches, blades of grass-as they had studied them and conceptualized their existence. Monet, on the other hand, wanted to paint what he saw rather than what he intellectually knew. And he saw not separate leaves, but splashes of constantly changing light and color. According to Seitz, "It is in this context that we must understand his desire to see the world through the eyes of a man born blind who had suddenly gained his sight: as a pattern of nameless color patches." In an important sense, then, Monet belongs to the tradition of Renaissance illusionism: in recording the phenomena of the natural world, he simply based his art on perceptual rather than conceptual knowledge.

During the 1880s, the Impressionists began to dissolve as a cohesive group, although individual members continued to see one another and they occasionally worked together. In 1883 Monet moved to Giverny, but he continued to travel-to London, Madrid, and Venice, as well as to favorite sites in his native country. He gradually gained critical and financial success during the late 1880s and the 1890s. This was due primarily to the efforts of Durand-Ruel, who sponsored one-man exhibitions of Monet's work as early as 1883 and who, in 1886, also organized the first large-scale Impressionist group show to take place in the United States.

Monet's painting during this period slowly gravitated toward a broader, more expansive and expressive style. In Spring Trees by a Lake (1888) the entire surface vibrates electrically with shimmering light and color. Paradoxically, as his style matured and as he continued to develop the sensitivity of his vision, the strictly illusionistic aspect of his paintings began to disappear. Plastic form dissolved into colored pigment, and three-dimensional space evaporated into a charged, purely optical surface atmosphere. His canvases, although invariably inspired by the visible world, increasingly declared themselves as objects that are, above all, paintings. This quality links Monet's art more closely with modernism than with the Renaissance tradition.

Modernist, too, are the "serial" paintings to which Monet devoted considerable energy during the 1890s. The most celebrated of these series are the haystacks (1891) and the façades of Rouen Cathedral (1892-1894). In these works Monet painted his subjects from more or less the same physical position, allowing only the natural light and atmospheric conditions to vary from picture to picture. That is, he "fixed" the subject matter, treating it like an experimental constant against which changing effects could be measured and recorded. This technique reflects the persistence and devotion with which Monet pursued his study of the visible world. At the same time, the serial works effectively neutralized subject matter per se, implying that paintings could exist without it. In this way his art established an important precedent for the development of abstract painting.

Late Work[edit | edit source]

Monet's wife died in 1879; in 1892 he married Alice Hoschedé. By 1899 his financial position was secure, and he began work on his famous series of water lily paintings. Water lilies existed in profusion in the artist's exotic gardens at Giverny, and he painted them tirelessly until his death there on December 5, 1926. Monet's late years were by no means easy. During his last two decades, he suffered from poor health and had double cataracts; by the 1920s, he was virtually blind. In addition to his physical ailments, Monet struggled desperately with the problems of his art. In 1920, he began work on 12 large canvases (each measuring 14 feet in width) of water lilies, which he planned to give to the state. To complete them, he fought against his own failing eyesight and against the demands of a large-scale mural art for which his own past had hardly prepared him. In effect, the task required him to learn a new kind of painting at the age of 80. The paintings are characterized by a broad, sweeping style; virtually devoid of subject matter, their vast, encompassing spaces are generated almost exclusively by color. Such color spaces were without precedent in Monet's lifetime; and moreover, their descendants have appeared in contemporary painting only since the end of World War II.

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895)[edit | edit source]

Born January 14, 1841, in Bourges, France. The daughter of a high-ranking government official and granddaughter of the influential Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Morisot began studying painting alongside her sister Edma when both were young. Though women were not allowed to join official arts institutions, like schools, until the last few years of the nineteenth century, Morisot and her sister earned a certain measure of respect within art circles for their budding talent. After copying masterpieces from the Louvre Museum in the late 1850s under Joseph Guichard, Berthe and Edma began painting outdoor scenes while studying with the well-known landscape painter Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot. Berthe Morisot worked with Corot, who became a family friend, from 1862 to 1868. She first exhibited her paintings at the prestigious state-run art show, the Salon, in 1864, and her work was shown there regularly for the next decade..

Morisot was greatly influenced by her friendship with Édouard Manet, to whom she was introduced in 1868 by their fellow artist Henri Fantin-Latour. Though Morisot was never a pupil of Manet's, she soon abandoned aspects of Corot's teachings and destroyed almost all of her early work in favor of a more unconventional and modern approach, with the encouragement of Manet and others, including Edgar Degas and Frédéric Bazille. She also played an important role in Manet's career, posing for a number of his paintings-notably The Balcony (1869) and Repose (c. 1870) - and encouraging him to adapt some tenets of Impressionism into his work.

Beginning in 1874, Morisot refused to show her work at the Salon, choosing to join a fledgling group of Impressionist painters that included Degas, who would become Morisot's lifelong friend, as well as Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, and Alfred Sisley. Morisot agreed to take part in the first independent exhibition of Impressionist paintings, which opened in a photographer's studio on Paris's Boulevard des Capucines in April 1874. In doing so, she went against the advice of Édouard Manet, who refused to exhibit with the Impressionists and was determined to make his name at the Salon. Among the paintings she showed at the exhibition were The Cradle, The Harbor at Cherbourg, Hide and Seek, and Reading.

In December 1874, at the age of 33, Morisot married Manet's younger brother, Eugène, also a painter. Eugène Manet supported his wife in her work and the marriage gave Morisot social and financial stability while she continued her painting career. On a census form, Morisot famously recorded herself as "without profession," underscoring her vision of her life and work within, not outside of, the traditional feminine sphere. She participated in all of the Impressionist exhibitions save one, in 1877, when she was pregnant with her daughter, Julie, born in 1878.

Morisot painted in oils, watercolors, and pastels, and produced numerous drawings. Her wide range of subjects included portraits (many of her sister Edma), landscapes, still lives, and the domestic scene, particularly traditional feminine occupations. A particularly notable example of the latter was Woman at Her Toilette (c. 1879), which she displayed in the fifth Impressionist exhibition in 1880. For some of her later works, Morisot noticeably changed her style, making numerous sketches of a subject before beginning a painting rather than relying on spontaneous observation, as in her earlier work. Paintings that showcased her new style included The Cherry Tree (1891-92) and Girl with a Greyhound (1893). Eugène Manet died in April 1892, after a long illness. Morisot's friends and fellow artists rallied around her and her young daughter Julie, and she continued to work. Though never commercially successful during her lifetime, Morisot outsold several of her fellow Impressionists, including Monet, Renoir, and Sisley. She had her first solo exhibition in 1892 at the Boussod and Valadon gallery, where she sold a number of works, and she earned further recognition in 1894, when the French government purchased her oil painting Young Woman in a Ball Gown. In the winter of 1894-95, Morisot contracted pneumonia. She died on March 2, 1895, at the age of 54. After her death, Renoir and Degas organized a retrospective of her work, which garnered serious critical acclaim and ensured her place in art history as one of the founding members of the revolutionary Impressionist movement.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)[edit | edit source]

Born February 25, 1841, in Limoges, France. Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Paris. Because he showed a remarkable talent for drawing, Renoir became an apprentice in a porcelain factory, where he painted plates. Later, after the factory had gone out of business, he worked for his older brother, decorating fans. Throughout these early years, Renoir made frequent visits to the Louvre, where he studied the art of earlier French masters, particularly those of the 18th century-Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, and Jean Honoré Fragonard. His deep respect for these artists informed his own painting throughout his career. During the 1870s, a revolution erupted in French painting. Encouraged by artists like Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, a number of young painters began to seek alternatives to the traditions of Western painting that had prevailed since the beginning of the Renaissance. These artists went directly to nature for their inspiration and into the actual society of which they were a part. As a result, their works revealed a look of freshness and immediacy that in many ways departed from the look of Old Master painting. The new art, for instance, displayed vibrant light and color instead of the somber browns and blacks that had dominated previous painting. These qualities, among others, signaled the beginning of modern art.

Early Career[edit | edit source]

In 1862, Renoir decided to study painting seriously and entered the Atelier Gleyre, where he met Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Jean Frédéric Bazille. During the next six years, Renoir's art showed the influence of Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, the two most innovative painters of the 1850s and 1860s. Courbet's influence is especially evident in the bold palette-knife technique of Diane Chasseresse (1867), while Manet's can be seen in the flat tones of Alfred Sisley and His Wife (1868). Still, both paintings reveal a sense of intimacy that is characteristic of Renoir's personal style.

The 1860s were difficult years for Renoir. At times he was too poor to buy paints or canvas, and the Salons of 1866 and 1867 rejected his works. The following year the Salon accepted his painting Lise. He continued to develop his work and to study the paintings of his contemporaries-not only Courbet and Manet, but Camille Corot and Eugène Delacroix as well. Renoir's indebtedness to Delacroix is apparent in the lush painter like that of the Odalisque (1870). Renoir and Impressionism In 1869, Renoir and Monet worked together at La Grenouillère, a bathing spot on the Seine. Both artists became obsessed with painting light and water. According to Phoebe Pool (1967), this was a decisive moment in the development of Impressionism, for "It was there that Renoir and Monet made their discovery that shadows are not brown or black but are colored by their surroundings, and that the 'local color' of an object is modified by the light in which it is seen, by reflections from other objects and by contrast with juxtaposed colors." The styles of Renoir and Monet were virtually identical at this time, an indication of the dedication with which they pursued and shared their new discoveries. During the 1870s, they still occasionally worked together, although their styles generally developed in more personal directions. In 1874, Renoir participated in the first Impressionist exhibition, along with Monet, Edgar Degas, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot. His works included The Opera Box (1874), a painting that shows the artist's penchant for rich and freely handled figurative expression. Of all the Impressionists, Renoir most consistently and thoroughly adapted the new style-in its inspiration, essentially a landscape style-to the great tradition of figure painting.

Although the Impressionist exhibitions were the targets of much public ridicule during the 1870s, Renoir's patronage gradually increased during the decade. He became a friend of Caillebotte, one of the first patrons of the Impressionists, and he was also backed by the art dealer Durand-Ruel and by collectors like Victor Choquet, the Charpentiers, and the Daidets. The artist's connection with these individuals is documented by a number of handsome portraits, for instance, Madame Charpentier and Her Children (1878).

In the 1870s, Renoir also produced some of his most celebrated Impressionist genre scenes, including The Swing and The Ball at the Moulin de la Galette (both 1876). These works embody his most basic attitudes about art and life. They show men and women together, openly and casually enjoying a society diffused with warm, radiant sunlight. Figures blend softly into one another and into their surrounding space. Such worlds are pleasurable, sensuous, and generously endowed with human feeling.

Renoir's "Dry" Period[edit | edit source]

During the 1880s, Renoir gradually separated himself from the other Impressionists, largely because he became dissatisfied with the direction the new style was taking in his own hands. In paintings like The Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881), he felt that his style was becoming too loose, that forms were losing their distinctiveness and sense of mass. As a result, he looked to the past for a fresh inspiration. In 1881, he traveled to Italy and was particularly impressed by the art of Raphael. During the next six years, Renoir's paintings became increasingly dry: he began to draw in a tight, classical manner, carefully outlining his figures in an effort to give them plastic clarity. The works from this period, such as The Umbrellas (1883) and Les grandes baigneuses (1884-1887), are generally considered the least successful of Renoir's mature expressions. Their classicizing effort seems self-conscious, a contradiction to the warm sensuality that came naturally to him.

Late Career[edit | edit source]

By the end of the 1880s, Renoir had passed through his dry period. His late work is truly extraordinary: a glorious outpouring of monumental nude figures, beautiful young girls, and lush landscapes. Examples of this style include The Music Lesson (1891), Young Girl Reading (1892), and Sleeping Bather (1897). In many ways, the generosity of feeling in these paintings expands upon the achievements of his great work in the 1870s. Renoir's health declined severely in his later years. In 1903, he suffered his first attack of rheumatoid arthritis and settled for the winter at Cagnes-sur-Mer. By this time he faced no financial problems, but the arthritis made painting painful and often impossible. Nevertheless, he continued to work, at times with a brush tied to his crippled hand. Renoir died at Cagnes-sur-Mer on December 3, 1919, but his death was preceded by an experience of supreme triumph: the state had purchased his portrait Madame Georges Charpentier (1877), and he traveled to Paris in August to see it hanging in the Louvre.

Edouard Manet (1832-1883)[edit | edit source]

Born January 23, 1832 in Paris, France, to Auguste Édouard Manet, an official at the Ministry of Justice, and Eugénie Désirée Manet. Manet's father, who had expected his son to study law, vigorously opposed his wish to become a painter. The career of naval officer was decided upon as a compromise, and at the age of 16 Édouard sailed to Rio de Janeiro on a training vessel. Upon his return he failed to pass the entrance examination of the naval academy. His father relented, and in 1850 Manet entered the studio of Thomas Couture, where, in spite of many disagreements with his teacher, he remained until 1856. During this period, Manet traveled abroad and made numerous copies after the Old Masters in both foreign and French public collections. Early Works Manet's entry for the Salon of 1859, The Absinthe Drinker, a thematically romantic but conceptually daring work, was rejected. At the Salon of 1861, his Spanish Singer, one of a number of works of Spanish character painted in this period, not only was admitted to the Salon but won an honorable mention and the acclaim of the poet Théophile Gautier. This was to be Manet's last success for many years.

In 1863, Manet married Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch pianist. That year he showed 14 paintings at the Martinet Gallery; one of them, Music in the Tuileries, remarkable for its freshness in the handling of a contemporary scene, was greeted with considerable hostility. Also in 1863, the Salon rejected Manet's large painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, or Luncheon on the Grass, and the artist elected to have it shown at the now famous Salon des Refusés, created by the emperor under the pressure of the exceptionally large number of painters whose work had been turned away. Here, Manet's picture attracted the most attention and brought forth a kind of abusive criticism that was to set a pattern for years to come.

In 1865, Manet's Olympia produced a still more violent reaction at the official Salon, and his reputation as a renegade became widespread. Upset by the criticism, Manet made a brief trip to Spain, where he admired many works by Diego Velázquez, to whom he referred as "the painter of painters."

Support of Baudelaire and Zola[edit | edit source]

Manet's close friend and supporter during the early years was Charles Baudelaire, who, in 1862, had written a quatrain to accompany one of Manet's Spanish subjects, Lola de Valence, and the public, largely as a result of the strange atmosphere of the Olympia, linked the two men readily. In 1866, after the Salon jury had rejected two of Manet's works, Émile Zola came to his defense with a series of articles filled with strongly expressed, uncompromising praise. In 1867, he published a book that contains the prediction, "Manet's place is destined to be in the Louvre." This book appears on Zola's desk in Manet's portrait of the writer (1868). In May of that year, the Paris World's Fair opened its doors, and Manet, at his own expense, exhibited 50 of his works in a temporary structure, not far from Gustave Courbet's private exhibition. This was in keeping with Manet's view, expressed years later to his friend Antonin Proust, that his paintings must be seen together in order to be fully understood.

Although Manet insisted that a painter be "resolutely of his own time" and that he paint what he sees, he nevertheless produced two important religious works, Dead Christ with Angels and Christ Mocked by the Soldiers, which were shown at the Salons of 1864 and 1865, respectively, and ridiculed. Only Zola could defend the former work on the grounds of its vigorous realism while playing down its alleged lack of piety. It is also true that although Manet despised the academic category of "history painting" he did paint the contemporary Naval Battle between the Kearsarge and the Alabama (1864) and The Execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico (1867). The latter is based upon a careful gathering of the facts surrounding the incident and composed, largely, after Francisco Goya's Executions of the Third of May, resulting in a curious amalgam of the particular and the universal. Manet's use of older works of art in elaborating his own major compositions has long been, and continues to be, a problematic subject, since the old view that this procedure was needed to compensate for the artist's own inadequate imagination is rapidly being discarded.

Late Works[edit | edit source]

Although Manet influenced the Impressionists during the 1860s, during the next decade it appears that it was he who learned from them. His palette became lighter; his stroke, without ever achieving the analytical intensity of Claude Monet's, was shorter and more rapid. Nevertheless, Manet never cultivated plein-airism seriously, and he remained essentially a figure and studio painter. Also, despite his sympathy for most of the Impressionists with whom the public associated him, he never exhibited with them at their series of private exhibitions, which began in 1874. He was particularly close to the female Impressionist Berthe Morisot, whom he met in 1868. Manet was a great influence on Morisot, and she in turn helped him accept some of the tenets of Impressionism to greater effect in his work; she also posed for him numerous times, notably for The Balcony (1869) and Repose (c. 1870). In 1874, Morisot married Manet's younger brother, Eugéne, also a painter. Manet had his first resounding success since The Spanish Singer at the Salon of 1873 with his Bon Bock, which radiates a touch and joviality of expression reminiscent of Frans Hals, in contrast to Manet's usually austere figures. In spite of the popularity of this painting, his success was not to extend to the following season. About this time he met the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, with whom he remained on intimate terms for the remainder of his life. After Manet's rejection by the jury in 1876, Mallarmé took up his defense.

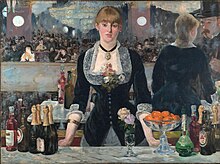

Toward the end of the 1870s, although Manet retained the bright palette and the touch of his Impressionist works, he returned to the figure problems of the early years. The undeniable sense of mystery is found again in several bar scenes, notably the Brasserie Reichshoffen, in which the relationships of the figures recall those of Luncheon on the Grass. Perhaps the apotheosis of his lifelong endeavors is to be found in his last major work, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1881-1882). Here, in the expression of the barmaid, is all the starkness of the great confrontations of the 1860s, but bathed in a profusion of colors. While we are drawn to the brilliantly painted accessories, it is the girl, placed at the center before a mirror, which dominates the composition and ultimately demands our attention. Although her reflected image, showing her to be in conversation with a man, is absorbed into the brilliant atmosphere of the setting, she remains enigmatic and aloof. Manet produced two aspects of the same personality, combined the fleeting with the eternal, and, by "misplacing" the reflected image, took a step toward abstraction as a solution to certain lifelong philosophical and technical problems. In 1881, Manet was finally admitted to membership in the Legion of Honor, an award he had long coveted. By then he was seriously ill. Therapy at the sanatorium at Bellevue failed to improve his health, and walking became increasingly difficult for him. In his weakened condition he found it easier to handle pastels than oils, and he produced a great many flower pieces and portraits in that medium. In the spring of 1883, his left leg was amputated, but this did not prolong his life. He died peacefully in Paris on April 30. Manet was short, unusually handsome, and witty. His biographers stress his kindness and unaffected generosity toward his friends. The paradoxical elements in his art are an extension of the man: although a revolutionary in art, he craved official honors; while fashionably dressed, he affected a Parisian slang at odds with his appearance and impeccable manners; and although he espoused the style of life of the conservative classes, his political sentiments were those of the republican liberal.

Bibliography[edit | edit source]

- Impressionism: Reflections and Perceptions, by Meyer Schapiro. Scholarly, yet accessible, with outstanding quality reproductions.

- Studies in Impressionism, by John Rewald. Another great art history writer, this is a series of essays.

- Art in the Making: Impressionism, by David Bomford. An interesting technical approach to the study of Impressionist paintings.

- Impressionists Side by Side: Their Friendships, Rivalries, and Artistic Exchanges, by Barbara White. Approaches the study of Impressionism from the personal relationships of the painters.

- Origins of Impressionism, the catalog from the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition. Excellent illustrations and text provide a background of the precursors of the Impressionists, Manet, Corot, Courbet, et al.

- Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, T.J. Clark's masterpiece looks at the Impressionist movement from the social context of Paris in the 1870s.

- Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas ,Charles Harrison (editor). A great anthology of texts from the 19th and 20th century by artists and art historians.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Grovier, Kelly. "A Bar at the Folies-Bergere: A symbol planted in cleavage". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

Major Artwork of this time[edit | edit source]

Post Impressionism-visible brushstrokes, similar to impressionism, but greater use of arbitrary color and crowded compositions

- Prominent Artists

- Paul Cézanne

- Paul Gauguin

- Henri Rousseau

- Georges Seurat

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

- Vincent van Gogh

The Fauve Movement-short lived art movement known for its intense colors

- Prominent Artists

- Henri Matisse

- André Derain

- Georges Braque

- Raul Dufy

- Georges Rouault

- Maurice de Vlaminck

Cubism-analytical and synthetic

- Prominent Artists

- Georges Braque

- Pablo Picasso

- Juan Gris

Surrealism-emphasized emotion, reality skewed, a reaction to the creation of realistic photography

- Prominent Artists

- Salvador Dalí

- René Magritte

- Max Ernst

- Joan Miró

Gallery[edit | edit source]

Hudson River School[edit | edit source]

-

The Oxbow by Thomas Cole - 1836.

-

Architect’s Dream by Thomas Cole - 1840.

-

Starrucca Viaduct by Jasper Francis Cropsey - 1865.

-

Among the Sierra Nevada, California by Albert Bierstadt - 1868.

Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, and Pointillism[edit | edit source]

-

Woman with a Parasol by Claude Monet - 1875. An example of Impressionism

-

Café Terrace at Night by Vincent van Gough - 1888.

-

Starry Night by Vincent van Gough - 1889. An example of Post-Impressionism.

-

Starry Night Over the Rhône by Vincent van Gough - 1889. An example of Post-Impressionism.

-

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat - 1884. An example of Pointillism.

-

Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon in 1890 by Paul Signac - 1890. An example of Neo-Impressionism and Pointillism.

-

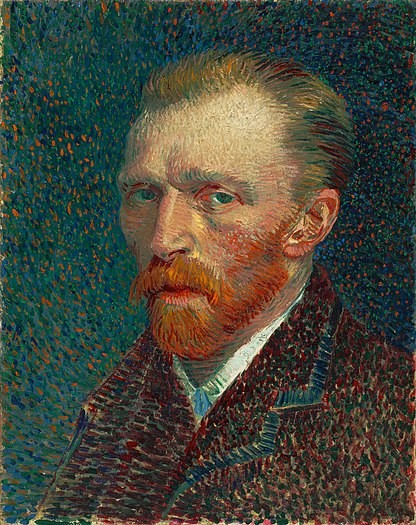

Self Portrait by Vincent van Gogh - 1887. An example of Pointillism.

-

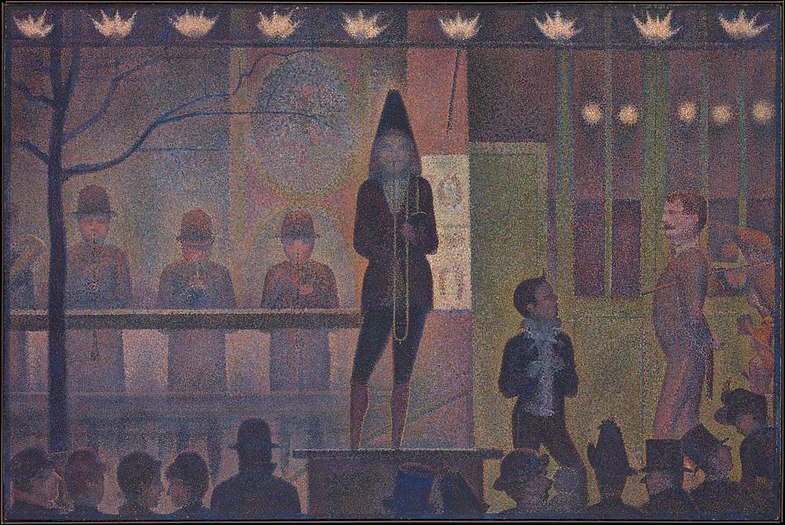

Parade de cirque by Georges Seurat - 1887-1888. An example of Neo-Impressionism and Pointillism.

Romanticism[edit | edit source]

-

Ossian receiving the Ghosts of the French Heroes attributed to Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson - 1801.

-

Napoleon Crossing the Alps by Jacques-Louis David - 1801.

-

The Morning by Philipp Otto Runge - 1808.

-

The Third of May by Francisco Goya. This event refers to an event in 1808. Painted in 1814.

-

Wanderer above the sea of fog by Caspar David Friedrich - 1817.

-

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven when composing the Missa Solemnis by Joseph Karl Stieler - 1820.

-

Saturn Devouring his Son by Francisco Goya - Between 1819 and 1823.

-

Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix - 1830.

-

Poem of the Soul - On the mountain by Louis Janmot - 1854.

Other[edit | edit source]

-

Reprint of The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai - between 1826 and 1833.

-

The Meeting, or Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet! by Gustave Courbet - 1854.

-

Jewish woman selling oranges by Aleksander Gierymski. Painted between 1880 and 1881.

-

Halévy Street, View from the Seventh Floor by Gustave Caillebotte - 1877.

-

The Wailing Wall by J.L. Gerome - 1880.

-

The Geography Lesson or "The Black Spot" by Albert Bettannier - 1887

-

The Scream by Edvard Munch - 1893.

Architecture[edit | edit source]

-

The White House Neoclassical and Palladian architecture finished in 1800.

-

US Capitol - 1800.

-

Arc de Triomphe Neoclassical architecture between 1806 and 1836.

-

The Palace of Westminster, this iconic iteration of the structure was rebuilt in the mid 1800's after the earlier structure was destroyed by fire.

-

Palais Garnier - 1875.

-

Washington Monument Obelisk - 1884.

-

Brooklyn Bridge - 1883.

-

Statue of Liberty by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi - 1886.

-

ʻIolani Palace A prime example of Hawaiian architecture - 1879.

-

Tour Eiffel Now an iconic symbol of France, this 1889 structure was controversial at the time.

-

Tower Bridge - 1894