World Cultures/Culture in Asia/Culture of Russia

Introduction

[edit | edit source]

The culture of the ethnic Russian people (along with the cultures of many other ethnicities with which it has intertwined in the territory of the Russian Federation and the former Soviet Union) has a long tradition of achievement in many fields,[1] especially when it comes to literature,[2] folk dancing,[3] philosophy, classical music,[4][5] traditional folk-music, ballet,[6] architecture, painting, cinema,[7] animation and politics. In all these areas Russia has had a considerable influence on world culture. Russia also has a rich material culture and a tradition in technology.

Russian culture grew from that of the East Slavs, with their pagan beliefs and specific way of life in the wooded, steppe and forest-steppe areas of Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Major influences on early Russian culture and East Slavic people in Russia included:

- nomadic Turkic people (Tatars, Kipchaks) and tribes of Iranian origin through intense cultural contacts in the Russian steppe

- Finno-Ugric peoples, Balts and Scandinavians (Germanic people) through the Russian North

- Goths in the Pontic littoral, who left linguistic traces in the early Russian dialects

- the people of the Byzantine Empire (especially Greeks) with whom the early Russians maintained strong cultural links[8]

In the late 1st millennium AD the Nordic sea culture of the Varangians (Scandinavian Vikings) and in the middle of the second millennium the nomadic peoples of the Mongol Empire also influenced Russian culture.[9][10][11] The fusion of Nordic-European and Oriental-Asian cultures shaped Early Slavic tribes in European Russia and helped to form the Russian identity in the Volga region and in the states of the Rus' Khaganate (Template:Circa 9th century AD) and Kievan Rus' (9th to 13th centuries). Orthodox Christian missionaries began arriving from the Eastern Roman Empire in the 9th century, and Kievan Rus' officially converted to Orthodox Christianity in 988. This largely defined the Russian culture of the next millennium as a synthesis of Slavic and Byzantine cultures.[12] Russia or Rus' formed, developed its culture and was influenced through its location by Western European and Asian cultures so that a Russian-Eurasian culture developed.[13]

After Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453, Russia remained the largest Orthodox nation in the world and eventually claimed succession to the Byzantine legacy in the form of the Third Rome idea. An important period in Russian history, the Tsardom of Muscovy from 1547 until 1721, saw many Russian cultural peculiarities emerge and develop. At different periods in Russian history, the culture of Western Europe also exerted strong influences over Russian citizens. During the era of the Russian Empire which existed from 1721 to 1917, the title of the rulers became officially westernised: Tsars claimed the title and rank of "Emperor". Following the reforms of Peter the Great (reigned 1682–1725) in the Russian Empire, for two centuries Russian "high culture" largely developed in the general context of European culture rather than pursuing its own unique ways.[14] The situation changed in the 20th century, when the distinctive Communist ideology - originally imported from Europe - became a major factor in the culture of the Soviet Union, where Russia, in the form of the Russian SFSR, was the largest and leading part. The culture of the Soviet Union has decisively shaped the former Soviet Russian Republic and thus Russian culture.

Although Russia has been influenced by Western Europe, the Eastern world, Northern cultures and the Byzantine Empire for more than 1000 years since ancient Rus' and is culturally connected with them, it is often arguedTemplate:By whom? that due to its history, geography and inhabitants (which belong to different language families but became embedded in the Russian language and culture), the country has developed a character with many aspects of a unique Russian civilization which in many parts differs from both Western and Eastern cultures.[15][16][17]

Nowadays,Template:When? the Nation Brands Index ranks Russian cultural heritage seventh in importance,[citation needed] based on interviews of some 20,000 people mainly from Western countries and from the Far East. Due to the relatively late involvement of Russia in modern globalization and in international tourism, many aspects of Russian culture, like Russian jokes and Russian art, remain largely unknown to foreigners.[18]

Language and literature

[edit | edit source]Russia's 160 ethnic groups speak some 100 languages.[1] According to the 2002 census, 142.6 million people speak Russian, followed by Tatar with 5.3 million and Ukrainian with 1.8 million speakers.[19] Russian is the only official state language, but the Constitution gives the individual republics the right to make their native language co-official next to Russian.[20] Despite its wide dispersal, the Russian language is homogeneous throughout Russia. Russian is the most geographically widespread language of Eurasia and the most widely spoken Slavic language.[21] Russian belongs to the Indo-European language family and is one of the living members of the East Slavic languages; the others being Belarusian and Ukrainian (and possibly Rusyn). Written examples of Old East Slavic (Old Russian) are attested from the 10th century onwards.[22]

Over a quarter of the world's scientific literature is published in Russian. Russian is also applied as a means of coding and storage of universal knowledge—60–70% of all world information is published in the English and Russian languages.[23] The language is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

Folklore

[edit | edit source]New Russian folklore takes its roots in the pagan beliefs of ancient Slavs, which is nowadays still represented in the Russian folklore. Epic Russian bylinas are also an important part of Slavic mythology. The oldest bylinas[check spelling] of Kievan cycle were actually recorded mostly in the Russian North, especially in Karelia, where most of the Finnish national epic Kalevala was recorded as well.

Many Russian fairy tales and bylinas were adapted for Russian animations, or for feature movies by famous directors like Aleksandr Ptushko (Ilya Muromets, Sadko) and Aleksandr Rou (Morozko, Vasilisa the Beautiful). Some Russian poets, including Pyotr Yershov and Leonid Filatov, created a number of well-known poetical interpretations of classical Russian fairy tales, and in some cases, like that of Alexander Pushkin, also created fully original fairy tale poems that became very popular.

Folklorists today consider the 1920s the Soviet Union's golden age of folklore. The struggling new government, which had to focus its efforts on establishing a new administrative system and building up the nation's backwards economy, could not be bothered with attempting to control literature, so studies of folklore thrived. There were two primary trends of folklore study during the decade: the formalist and Finnish schools. Formalism focused on the artistic form of ancient byliny and faerie tales, specifically their use of distinctive structures and poetic devices.[24] The Finnish school was concerned with connections amongst related legends of various Eastern European regions. Finnish scholars collected comparable tales from multiple locales and analyzed their similarities and differences, hoping to trace these epic stories’ migration paths.[25]

Once Joseph Stalin came to power and put his first five-year plan into motion in 1928, the Soviet government began to criticize and censor folklore studies. Stalin and the Soviet regime repressed folklore, believing that it supported the old tsarist system and a capitalist economy. They saw it as a reminder of the backward Russian society that the Bolsheviks were working to surpass.[27] To keep folklore studies in check and prevent "inappropriate" ideas from spreading amongst the masses, the government created the RAPP – the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers. The RAPP specifically focused on censoring fairy tales and children's literature, believing that fantasies and "bourgeois nonsense" harmed the development of upstanding Soviet citizens. Fairy tales were removed from bookshelves and children were encouraged to read books focusing on nature and science.[28] RAPP eventually increased its levels of censorship and became the Union of Soviet Writers in 1932.

In order to continue researching and analyzing folklore, intellectuals needed to justify its worth to the Communist regime. Otherwise, collections of folklore, along with all other literature deemed useless for the purposes of Stalin's Five Year Plan, would be an unacceptable realm of study. In 1934, Maksim Gorky gave a speech to the Union of Soviet Writers arguing that folklore could, in fact, be consciously used to promote Communist values. Apart from expounding on the artistic value of folklore, he stressed that traditional legends and fairy tales showed ideal, community-oriented characters, which exemplified the model Soviet citizen.[29] Folklore, with many of its conflicts based on the struggles of a labor-oriented lifestyle, was relevant to Communism as it could not have existed without the direct contribution of the working classes.[30] Also, Gorky explained that folklore characters expressed high levels of optimism, and therefore could encourage readers to maintain a positive mindset, especially as their lives changed with the further development of Communism.[25]

Yuri Sokolov, the head of the folklore section of the Union of Soviet Writers also promoted the study of folklore by arguing that folklore had originally been the oral tradition of the working people, and consequently could be used to motivate and inspire collective projects amongst the present-day proletariat.[31] Characters throughout traditional Russian folktales often found themselves on a journey of self-discovery, a process that led them to value themselves not as individuals, but rather as a necessary part of a common whole. The attitudes of such legendary characters paralleled the mindset that the Soviet government wished to instill in its citizens.[32] He also pointed out the existence of many tales that showed members of the working class outsmarting their cruel masters, again working to prove folklore's value to Soviet ideology and the nation's society at large.[33] Convinced by Gorky and Sokolov's arguments, the Soviet government and the Union of Soviet Writers began collecting and evaluating folklore from across the country. The Union handpicked and recorded particular stories that, in their eyes, sufficiently promoted the collectivist spirit and showed the Soviet regime's benefits and progress. It then proceeded to redistribute copies of approved stories throughout the population. Meanwhile, local folklore centers arose in all major cities.[34] Responsible for advocating a sense of Soviet nationalism, these organizations ensured that the media published appropriate versions of Russian folktales in a systematic fashion.[25]

Apart from circulating government-approved fairy tales and byliny that already existed, during Stalin's rule authors parroting appropriate Soviet ideologies wrote Communist folktales and introduced them to the population. These contemporary folktales combined the structures and motifs of the old byliny with contemporary life in the Soviet Union. Called noviny, these new tales were considered the renaissance of the Russian epic.[35] Folklorists were called upon to teach modern folksingers the conventional style and structure of the traditional byliny. They also explained to the performers the appropriate types of Communist ideology that should be represented in the new stories and songs[36] As the performers of the day were often poorly educated, they needed to obtain a thorough understanding of Marxist ideology before they could be expected to impart folktales to the public in a manner that suited the Soviet government. Besides undergoing extensive education, many folk performers traveled throughout the nation in order to gain insight into the lives of the working class, and thus communicate their stories more effectively.[37] Due to their crucial role in spreading Communist ideals throughout the Soviet Union, eventually some of these performers became highly valued members of Soviet society. A number of them, despite their illiteracy, were even elected as members of the Union of Soviet Writers.[38]

These new Soviet fairy tales and folk songs primarily focused on the contrasts between a miserable life in old tsarist Russia and an improved one under Stalin's leadership.[39] Their characters represented identities for which Soviet citizens should strive, exemplifying the traits of the "New Soviet Man."[40] The heroes of Soviet tales were meant to portray a transformed and improved version of the average citizen, giving the reader a clear goal for an ideal community-oriented self that the future he or she was meant to become. These new folktales replaced magic with technology, and supernatural forces with Stalin.[41] Instead of receiving essential advice from a mythical being, the protagonist would be given advice from omniscient Stalin. If the character followed Stalin's divine advice, he could be assured success in all his endeavors and a complete transformation into the "New Soviet Man."[42] The villains of these contemporary fairy tales were the Whites and their leader Idolisce, "the most monstrous idol," who was the equivalent of the tsar. Descriptions of the Whites in noviny mirrored those of the Tartars in byliny.[43] In these new stories, the Whites were incompetent, stagnant capitalists, while the Soviet citizens became invincible heroes.[44]

Once Stalin died in March 1953, folklorists of the period quickly abandoned the new folktales. Written by individual authors and performers, noviny did not come from the oral traditions of the working class. Consequently, today they are considered pseudo-folklore, rather than genuine Soviet (or Russian) folklore.[45] Without any true connection to the masses, there was no reason noviny should be considered anything other than contemporary literature. Specialists decided that attempts to represent contemporary life through the structure and artistry of the ancient epics could not be considered genuine folklore.[46] Stalin's name has been omitted from the few surviving pseudo-folktales of the period.[45] Instead of considering folklore under Stalin a renaissance of the traditional Russian epic, today it is generally regarded as a period of restraint and falsehood.

Literature

[edit | edit source]Russian literature is considered to be among the most influential and developed in the world, with some of the most famous literary works belonging to it.[2] Russia's literary history dates back to the 10th century; in the 18th century its development was boosted by the works of Mikhail Lomonosov and Denis Fonvizin, and by the early 19th century a modern native tradition had emerged, producing some of the greatest writers of all time. This period and the Golden Age of Russian Poetry began with Alexander Pushkin, considered to be the founder of modern Russian literature and often described as the "Russian Shakespeare" or the "Russian Goethe".[47] It continued in the 19th century with the poetry of Mikhail Lermontov and Nikolay Nekrasov, dramas of Aleksandr Ostrovsky and Anton Chekhov, and the prose of Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Ivan Goncharov, Aleksey Pisemsky and Nikolai Leskov. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in particular were titanic figures, to the point that many literary critics have described one or the other as the greatest novelist ever.[48][49]

By the 1880s Russian literature had begun to change. The age of the great novelists was over and short fiction and poetry became the dominant genres of Russian literature for the next several decades, which later became known as the Silver Age of Russian Poetry. Previously dominated by realism, Russian literature came under strong influence of symbolism in the years between 1893 and 1914. Leading writers of this age include Valery Bryusov, Andrei Bely, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Aleksandr Blok, Nikolay Gumilev, Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Fyodor Sologub, Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, Leonid Andreyev, Ivan Bunin, and Maxim Gorky.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing civil war, Russian cultural life was left in chaos. Some prominent writers, like Ivan Bunin and Vladimir Nabokov left the country, while a new generation of talented writers joined together in different organizations with the aim of creating a new and distinctive working-class culture appropriate for the new state, the Soviet Union. Throughout the 1920s writers enjoyed broad tolerance. In the 1930s censorship over literature was tightened in line with Joseph Stalin's policy of socialist realism. After his death the restrictions on literature were eased, and by the 1970s and 1980s, writers were increasingly ignoring official guidelines. The leading authors of the Soviet era included Yevgeny Zamiatin, Isaac Babel, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Ilf and Petrov, Yury Olesha, Mikhail Bulgakov, Boris Pasternak, Mikhail Sholokhov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, and Andrey Voznesensky.

The Soviet era was also the golden age of Russian science fiction, that was initially inspired by western authors and enthusiastically developed with the success of Soviet space program. Authors like Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Kir Bulychev, Ivan Yefremov, Alexander Belyaev enjoyed mainstream popularity at the time. An important theme of Russian literature has always been the Russian soul.

| Pushkin (1799–1837) |

Gogol (1809–1852) |

Turgenev (1818–1883) |

Dostoevsky (1821–1881) |

Tolstoy (1828–1910) |

Chekhov (1860–1904) |

Bulgakov (1891–1940) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Philosophy

[edit | edit source]Some Russian writers, like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, are known also as philosophers, while many more authors are known primarily for their philosophical works. Russian philosophy blossomed since the 19th century, when it was defined initially by the opposition of Westernizers, advocating Russia's following the Western political and economical models, and Slavophiles, insisting on developing Russia as a unique civilization. The latter group includes Nikolai Danilevsky and Konstantin Leontiev, the early founders of eurasianism.

In its further developments, Russian philosophy was always marked by a deep connection to literature and interest in creativity, society, politics and nationalism; cosmos and religion were other primary subjects. Notable philosophers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries include Vladimir Solovyov, Sergei Bulgakov, Pavel Florensky, Nikolai Berdyaev, Vladimir Lossky and Vladimir Vernadsky. In the 20th century Russian philosophy became dominated by Marxism.

| Bakunin (1814–1876) |

Kropotkin (1842–1921) |

Solovyov (1853–1900) |

Shestov (1866–1938) |

Berdyaev (1874–1948) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Humour

[edit | edit source]Russia owes much of its wit to the great flexibility and richness of the Russian language, allowing for puns and unexpected associations. As with any other nation, its vast scope ranges from lewd jokes and silly word play to political satire.

Russian jokes, the most popular form of Russian humour, are short fictional stories or dialogues with a punch line. Russian joke culture features a series of categories with fixed and highly familiar settings and characters. Surprising effects are achieved by an endless variety of plots. Russians love jokes on topics found everywhere in the world, be it politics, spouse relations, or mothers-in-law.

Chastushka, a type of traditional Russian poetry, is a single quatrain in trochaic tetrameter with an "abab" or "abcb" rhyme scheme. Usually humorous, satirical, or ironic in nature, chastushkas are often put to music as well, usually with balalaika or accordion accompaniment. The rigid, short structure (and to a lesser degree, the type of humor these use) parallels limericks. The name originates from the Russian word части́ть, meaning "to speak fast."

Visual arts

[edit | edit source]Russian visual artworks are similar in style with the ones from other eastern Slavic countries, like Ukraine or Belarus.

As early as the 12th and 13th centuries Russia had its national masters who were free of all foreign influence, i. e. that of the Greeks on the one hand, and on the other hand that of the Lombard master-masons called in Andrei Georgievich to build the Uspensky (Assumption) Cathedral in the city of Vladimir. Russia's relations with the Greek world were hampered by the Mongol invasion, and it is to the isolation arising from this that we must attribute the originality of Slavo-Russian ornamentation, which has a character of its own, quite unlike the Byzantine style and its derivative, the Romanesque.

-

Kremlin Tower Clock; 1913; rhodonite, silver, enamel, emeralds, sapphires; by House of Fabergé; Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Russian tea set; by Peter Carl Fabergé; made before 1896; silver gilt and opaque cloisonne enamel; Cleveland Museum of Art (USA)

-

Kovsh (wine vessel); by Fedor I. Rückert; 1896-1906; overall: 8.3 x 20.4 x 12.7 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Lilies of the Valley, a Fabergé egg; by Peter Carl Fabergé; 1898; enamel, gold, diamonds, rubies & pearls; 15.1 cm (5.9 in) when is closed; Fabergé Museum (Saint Petersburg, Russia)

Architecture

[edit | edit source]Russian architecture began with the woodcraft buildings of ancient Slavs. Some characteristics taken from the Slavic pagan temples are the exterior galleries and the plurality of towers. Since the Christianization of Kievan Rus', for several centuries Russian architecture was influenced predominantly by the Byzantine architecture, until the Fall of Constantinople. Apart from fortifications (kremlins), the main stone buildings of ancient Rus' were Orthodox churches, with their many domes, often gilded or brightly painted. Aristotle Fioravanti and other Italian architects brought Renaissance trends into Russia. The 16th century saw the development of unique tent-like churches culminating in Saint Basil's Cathedral. By that time the onion dome design was also fully developed. In the 17th century, the "fiery style" of ornamentation flourished in Moscow and Yaroslavl, gradually paving the way for the Naryshkin baroque of the 1690s. After Peter the Great reforms had made Russia much closer to Western culture, the change of the architectural styles in the country generally followed that of Western Europe.

The 18th-century taste for Rococo architecture led to the splendid works of Bartolomeo Rastrelli and his followers. During the reign of Catherine the Great and her grandson Alexander I, the city of Saint Petersburg was transformed into an outdoor museum of Neoclassical architecture. The second half of the 19th century was dominated by the Byzantine and Russian Revival style (this corresponds to Gothic Revival in Western Europe). Prevalent styles of the 20th century were the Art Nouveau (Fyodor Shekhtel), Constructivism (Moisei Ginzburg and Victor Vesnin), and the Stalin Empire style (Boris Iofan). After Stalin's death a new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, condemned the "excesses" of the former architectural styles, and in the late Soviet era the architecture of the country was dominated by plain functionalism. This helped somewhat to resolve the housing problem, but created the large massives of buildings of low architectural quality, much in contrast with the previous bright architecture. After the end of the Soviet Union the situation improved. Many churches demolished in the Soviet times were rebuilt, and this process continues along with the restoration of various historical buildings destroyed in World War II. As for the original architecture, there is no more any common style in modern Russia, though International style has a great influence.

Some notable Russian buildings include:

- Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod | Golden Gate (Vladimir) | Cathedral of Christ the Saviour | Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir | Cathedral of the Annunciation | Cathedral of the Archangel | Cathedral of the Dormition | Church of the Savior on Blood | Saint Basil's Cathedral | Kazan Kremlin | Saint Isaac's Cathedral | Kazan Cathedral | Peter and Paul Cathedral | Sukharev Tower | Menshikov Tower | Moscow Manege | Narva Triumphal Gate | Kolomenskoye | Peterhof Palace | Gatchina | Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra | Solovetsky Monastery | Kunstkamera | Russian Museum | Catherine Palace | Grand Kremlin Palace | Winter Palace | Simonov Monastery | Novodevichy Convent | Lenin's Mausoleum | Tatlin's Tower | Palace of the Soviets | Seven Sisters (Moscow) | All-Soviet Exhibition Centre | Ostankino Tower | Triumph-Palace | White House of Russia

-

Kronstadt Naval Cathedral in Saint Petersburg

-

Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow

-

Dormition Cathedral in Moscow

-

Spasskaya Tower from the Moscow Kremlin

-

Saint Basil's Cathedral in Moscow

-

Saint Isaac's Cathedral from Saint Petersburg

-

Königsberg Cathedral in Kaliningrad

-

The Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow

-

Church of the Savior on Blood in Saint Petersburg

-

The Winter Palace from Saint Petersburg

-

GUM in Moscow

-

Peter and Paul Fortress in Saint Petersburg

-

Kazan Cathedral in Saint Petersburg

-

The main building of Moscow State University in Moscow

-

General Staff Building in Saint Petersburg

-

Kunstkamera in Saint Petersburg

Handicraft

[edit | edit source]Matryoshka doll is a Russian nesting doll. A set of Matryoshka dolls consist of a wooden figure which can be pulled apart to reveal another figure of the same sort but somewhat smaller inside. It has in turn another somewhat smaller figure inside, and so on. The number of nested figures is usually six or more. The shape is mostly cylindrical, rounded at the top for the head and tapered towards the bottom, but little else. The dolls have no extremities, (except those that are painted). The true artistry is in the painting of each doll, which can be extremely elaborate. The theme is usually peasant girls in traditional dress, but can be almost anything; for instance, fairy tales or Soviet leaders.

Other forms of Russian handicraft include khokhloma, Dymkovo toy, gzhel, Zhostovo painting, Filimonov toys, pisanka, Pavlovo Posad shawl, Rushnyk, and palekh.

-

A Gzhel samovar

-

Matryoshka dolls in a market

-

Matryoshka doll

-

A Khokhloma painting on a cutting board

-

Dymkovo toys in a store

-

A Zhostovo painting

-

Some Filimonovo toys

-

Pysankas

-

Lacquered box with a Kholuy miniature, depicting the town of Suzdal

-

A Permogorsk painting on wood

-

Rushnyk, old traditional Russian weaving style. The patterns vary between regions, and can be found across Russian history in textiles and Russian architecture

Icon painting

[edit | edit source]

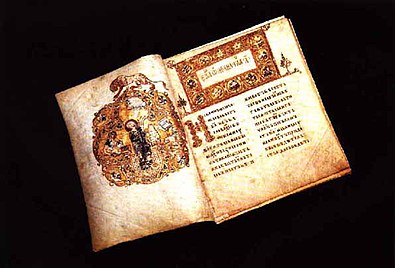

Russian icons are typically paintings on wood, often small, though some in churches and monasteries may be as large as a table top. Many religious homes in Russia have icons hanging on the wall in the krasny ugol, the "red" or "beautiful" corner (see Icon Corner). There is a rich history and elaborate religious symbolism associated with icons. In Russian churches, the nave is typically separated from the sanctuary by an iconostasis (Russian ikonostás) a wall of icons. Icon paintings in Russia attempted to help people with their prayers without idolizing the figure in the painting. The most comprehensive collection of Icon art is found at the Tretyakov Gallery.[50]

The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' following its conversion to Orthodox Christianity from the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in 988 AD. As a general rule, these icons strictly followed models and formulas hallowed by usage, some of which had originated in Constantinople. As time passed, the Russians—notably Andrei Rublev and Dionisius—widened the vocabulary of iconic types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere. The personal, improvisatory and creative traditions of Western European religious art are largely lacking in Russia before the seventeenth century, when Simon Ushakov's painting became strongly influenced by religious paintings and engravings from Protestant as well as Catholic Europe.

In the mid-seventeenth century, changes in liturgy and practice instituted by Patriarch Nikon resulted in a split in the Russian Orthodox Church. The traditionalists, the persecuted "Old Ritualists" or "Old Believers", continued the traditional stylization of icons, while the State Church modified its practice. From that time icons began to be painted not only in the traditional stylized and nonrealistic mode, but also in a mixture of Russian stylization and Western European realism, and in a Western European manner very much like that of Catholic religious art of the time. The Stroganov movement and the icons from Nevyansk rank among the last important schools of Russian icon-painting.

-

Icon of the Crucifixion; circa 1360; by the Novgorod School; Louvre (Paris)

-

Holy Trinity, Hospitality of Abraham; by Andrei Rublev; c. 1411; tempera on panel; 1.1 x 1.4 m (4 ft 8 in x 3 ft 8¾ in); Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow)

-

A three-leaved fold with the image of the "Annunciation", "Trinity" and "Presentation"; the end of the 17th century; temperaon wood; 13 x 7.3 cm; National Art Museum of Azerbaijan (Baku)

-

Icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker (Dvorischensky); 18th century; wood, gesso & tempera; Ryabushinsky Museum of Icons and Paintings (Moscow)

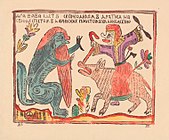

Lubok

[edit | edit source]A lubok (plural Lubki, Cyrillic: ) is a Russian popular print, characterized by simple graphics and narratives derived from literature, religious stories and popular tales. Lubki prints were used as decoration in houses and inns. Early examples from the late 17th and early 18th centuries were woodcuts, then engravings or etchings were typical, and from the mid-19th century lithography. They sometimes appeared in series, which might be regarded as predecessors of the modern comic strip. Cheap and simple books, similar to chapbooks,[51] which mostly consisted of pictures, are called lubok literature or (Cyrillic: ). Both pictures and literature are commonly referred to simply as lubki. The Russian word lubok derives from lub – a special type of board that pictures were printed on.

-

Baba Yaga riding a pig and fighting the infernal Crocodile; 17th century

-

The sun, moon, seasons and 12 months in the form of signs of the zodiac; the end of the 17th-early 18th century

-

The Mice are burying the Cat; 18th century

-

Farnos the Red Nose (lubok depicting a pig-riding jester); 18th century

Classical painting

[edit | edit source]The Russian Academy of Arts was created in 1757 with the aim of giving Russian artists an international role and status. Notable portrait painters from the Academy include Ivan Argunov, Fyodor Rokotov, Dmitry Levitzky, and Vladimir Borovikovsky.

In the early 19th century, when neoclassicism and romantism flourished, famous academic artists focused on mythological and Biblical themes, like Karl Briullov and Alexander Ivanov.

Realist painting

[edit | edit source]

Realism came into dominance in the 19th century. The realists captured Russian identity in landscapes of wide rivers, forests, and birch clearings, as well as vigorous genre scenes and robust portraits of their contemporaries. Other artists focused on social criticism, showing the conditions of the poor and caricaturing authority; critical realism flourished under the reign of Alexander II, with some artists making the circle of human suffering their main theme. Others focused on depicting dramatic moments in Russian history. The Peredvizhniki (wanderers) group of artists broke with Russian Academy and initiated a school of art liberated from Academic restrictions. Leading realists include Ivan Shishkin, Arkhip Kuindzhi, Ivan Kramskoi, Vasily Polenov, Isaac Levitan, Vasily Surikov, Viktor Vasnetsov and Ilya Repin.

By the turn of the 20th century and on, many Russian artists developed their own unique styles, neither realist nor avante-garde. These include Boris Kustodiev, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Mikhail Vrubel and Nicholas Roerich. Many works by the Peredvizhniki group of artists have been highly sought after by collectors in recent years. Russian art auctions during Russian Art Week in London have increased in demand and works have been sold for record breaking prices.

Russian avant-garde

[edit | edit source]The Russian avant-garde is an umbrella term used to define the large, influential wave of modernist art that flourished in Russia from approximately 1890 to 1930. The term covers many separate, but inextricably related, art movements that occurred at the time; namely neo-primitivism, suprematism, constructivism, rayonism, and futurism. Notable artists from this era include El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky, Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, Pavel Filonov and Marc Chagall. The Russian avant-garde reached its creative and popular height in the period between the Russian Revolution of 1917 and 1932, at which point the revolutionary ideas of the avant-garde clashed with the newly emerged conservative direction of socialist realism.

In the 20th century many Russian artists made their careers in Western Europe, forced to emigrate by the Revolution. Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall, Naum Gabo and others spread their work, ideas, and the impact of Russian art globally.

-

The glass; by Mikhail Larionov; 1912; oil on canvas; 104 × 97 cm (40.9 × 38.1 in.); Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York City)

-

Squares with Concentric Circles; by Wassily Kandinsky; 1913; watercolor, gouache and crayon on paper; height: 23.9 cm (9.4 in.), width: 31.6 cm (12.4 in.); Lenbachhaus (Munich, Germany)

-

Cyclist; by Natalia Goncharova; 1913; oil on canvas; height: 78 cm (30.7 in.), width: 105 cm (41.3 in.); the Russian State Museum (Saint Petersburg)

-

Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge; by El Lissitzky; 1919; poster (lithography)

Soviet art

[edit | edit source]During the Russian Revolution a movement was initiated to put all arts to service of the dictatorship of the proletariat. The instrument for this was created just days before the October Revolution, known as Proletkult, an abbreviation for "Proletarskie kulturno-prosvetitelnye organizatsii" (Proletarian Cultural and Enlightenment Organizations). A prominent theorist of this movement was Alexander Bogdanov. Initially, Narkompros (ministry of education), which was also in charge of the arts, supported Proletkult. Although Marxist in character, the Proletkult gained the disfavor of many party leaders, and by 1922 it had declined considerably. It was eventually disbanded by Stalin in 1932. De facto restrictions on what artists could paint were abandoned by the late 1980s.

However, in the late Soviet era many artists combined innovation with socialist realism including Ernst Neizvestny, Ilya Kabakov, Mikhail Shemyakin, Igor Novikov, Erik Bulatov, and Vera Mukhina. They employed techniques as varied as primitivism, hyperrealism, grotesque, and abstraction. Soviet artists produced works that were furiously patriotic and anti-fascist in the 1940s. After the Great Patriotic War Soviet sculptors made multiple monuments to the war dead, marked by a great restrained solemnity.

Performance arts

[edit | edit source]Russian folk music

[edit | edit source]

Russians have distinctive traditions of folk music. Typical ethnic Russian musical instruments are gusli, balalaika, zhaleika, balalaika contrabass, bayan accordion, Gypsy guitar and garmoshka. Folk music had great influence on the Russian classical composers, and in modern times it is a source of inspiration for a number of popular folk bands, most prominent being Golden Ring, Ural's Nation Choir, Lyudmila Zykina. Russian folk songs, as well as patriotic songs of the Soviet era, constitute the bulk of repertoire of the world-renowned Red Army choir and other popular Russian ensembles.

Russian folk dance

[edit | edit source]Russian folk dance (Russian: Русский Народный Танец ) can generally be broken up into two main types of dances Khorovod (Russian: Хоровод), a circular game type dance where the participants hold hands, sing, and the action generally happens in the middle of circle, and Plyaska (Russian: Пляска or Плясовый), a circular dance for men and women that increases in diversity and tempo, according to Bob Renfield, considered to be the preeminent scholar on the topic. Other forms of Russian Folk Dance include Pereplyas (Russian: Перепляс), an all-male competitive dance, Mass Dance (Russian: Массовый пляс), an unpaired stage dance without restrictions on age or number of participants, Group Dance (Russian: Групповая пляска) a type of mass dance employs simple round-dance passages, and improvisation, and types of Quadrilles (Russian: Кадриль), originally a French dance brought to Russia in the 18th century.

Ethnic Russian dances include khorovod (Russian: Хоровод), barynya (Russian: Барыня), kamarinskaya (Russian: Камаринская), kazachok (Russian: Казачок) and chechotka (Russian: Чечётка) (a tap dance in bast shoes and with a bayan). Troika (Russian: Тройка) A dance with one man and two women, named after the traditional Russian carriage which is led by three horses. Bear Dance or dancing with bears (Russian: Танец С Медведем) Dates back to 907 when Great Russian Prince Oleg, in celebration of his victory over the Greeks in Kiev, had as entertainment, 16 male dancers dress as bears and four bears dress as dancers . Dances with dancers dressed as bears are a recurring theme, as seen a recording of the Omsk Russian Folk Chorus.[52] One of the main characteristics of Russian furious dances is the Russian squat dance elements.[53][54]

Classical music

[edit | edit source]Music in 19th-century Russia was defined by the tension between classical composer Mikhail Glinka along with the other members of The Mighty Handful, who embraced Russian national identity and added religious and folk elements to their compositions, and the Russian Musical Society led by composers Anton and Nikolay Rubinstein, which was musically conservative. The later Romantic tradition of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, one of the most popular composers of the Romantic era, whose music has come to be known and loved for its distinctly Russian character as well as its rich harmonies and stirring melodies, was brought into the 20th century by Sergei Rachmaninoff, one of the last great champions of the Romantic style of European classical music.[55]

World-renowned composers of the 20th century included Alexander Scriabin, Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich and Georgy Sviridov. During most of the Soviet Era, music was highly scrutinized and kept within a conservative, accessible idiom in conformity with the policy of socialist realism.

Soviet and Russian conservatories have turned out generations of world-renowned soloists. Among the best known are violinists David Oistrakh and Gidon Kremer; cellist Mstislav Rostropovich; pianists Vladimir Horowitz, Sviatoslav Richter, and Emil Gilels; and vocalists Fyodor Shalyapin, Galina Vishnevskaya, Anna Netrebko and Dmitry Hvorostovsky.[4]

| Glinka (1804–1857) |

Mussorgsky (1839–1881) |

Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) |

Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) |

Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) |

Stravinsky (1882–1971) |

Shostakovich (1906–1975) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ballet

[edit | edit source]

The original purpose of the ballet in Russia was to entertain the imperial court. The first ballet company was the Imperial School of Ballet in St. Petersburg in the 1740s. The Ballets Russes was a ballet company founded in the 1909 by Sergey Diaghilev, an enormously important figure in the Russian ballet scene. Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes' travels abroad profoundly influenced the development of dance worldwide.[6] The headquarters of his ballet company was located in Paris, France. A protégé of Diaghilev, George Balanchine, founded the New York City Ballet Company in 1948.

During the early 20th century, Russian ballet dancers Anna Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky rose to fame. Soviet ballet preserved the perfected 19th century traditions,[56] and the Soviet Union's choreography schools produced one internationally famous star after another, including Maya Plisetskaya, Rudolf Nureyev, and Mikhail Baryshnikov. The Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow and the Mariinsky in Saint Petersburg remain famous throughout the world.[5]

Opera

[edit | edit source]The first known opera made in Russia was A Life for the Tsar by Mikhail Glinka in 1836. This was followed by several operas such as Ruslan and Lyudmila in 1842. Russian opera was originally a combination of Russian folk music and Italian opera. After the October revolution many opera composers left Russia. Russia's most popular operas include Boris Godunov, Eugene Onegin, The Golden Cockerel, Prince Igor, and The Queen of Spades.

Modern music

[edit | edit source]

Since the late Soviet times Russia has experienced another wave of Western cultural influence, which led to the development of many previously unknown phenomena in the Russian culture. The most vivid example, perhaps, is the Russian rock music, which takes its roots both in the Western rock and roll and heavy metal, and in traditions of the Russian bards of Soviet era, like Vladimir Vysotsky and Bulat Okudzhava. Saint-Petersburg (former Leningrad), Yekaterinburg (former Sverdlovsk) and Omsk became the main centers of development of the rock music. Popular Russian rock groups include Mashina Vremeni, Slot, DDT, Aquarium, Alisa, Kino, Nautilus Pompilius, Aria, Grazhdanskaya Oborona, Splean and Korol i Shut. At the same time Russian pop music developed from what was known in the Soviet times as estrada into full-fledged industry, with some performers gaining international recognition, like t.A.T.u. in the West, who have been said to be the most influential artists to ever come out of Russia, or Vitas in China. Another kind of music, Hardbass, has become an internet meme.

Cinema of Russia

[edit | edit source]While in the industrialized nations of the West, motion pictures had first been accepted as a form of cheap recreation and leisure for the working class, Russian filmmaking came to prominence following the 1917 revolution when it explored editing as the primary mode of cinematic expression.[57] Russian and later Soviet cinema was a hotbed of invention in the period immediately following the 1917 revolution, resulting in world-renowned films such as Battleship Potemkin.[7] Soviet-era filmmakers, most notably Sergei Eisenstein and Andrei Tarkovsky, would become some of the world's most innovative and influential directors.

Eisenstein was a student of filmmaker and theorist Lev Kuleshov, who developed the groundbreaking Soviet montage theory of film editing at the world's first film school, the All-Union Institute of Cinematography. Dziga Vertov, whose kino-glaz ("film-eye") theory—that the camera, like the human eye, is best used to explore real life—had a huge impact on the development of documentary film making and cinema realism. In 1932, Stalin made socialist realism the state policy; this somewhat limited creativity, however many Soviet films in this style were artistically successful, like Chapaev, The Cranes Are Flying, and Ballad of a Soldier.[7]

1960s and 1970s saw a greater variety of artistic styles in the Soviet cinema. Eldar Ryazanov's and Leonid Gaidai's comedies of that time were immensely popular, with many of the catch phrases still in use today. In 1961–1967 Sergey Bondarchuk directed an Oscar-winning film adaptation of Tolstoy's epic War and Peace, which was the most expensive Soviet film made.[58] In 1969, Vladimir Motyl's White Sun of the Desert was released, a very popular film in a genre known as 'osterns'; the film is traditionally watched by cosmonauts before any trip into space.[59]

The late 1980s and 1990s were a period of crisis in Russian cinema and animation. Although Russian filmmakers became free to express themselves, state subsidies were drastically reduced, resulting in fewer films produced. The early years of the 21st century have brought increased viewership and subsequent prosperity to the industry on the back of the economy's rapid development, and production levels are already higher than in Britain and Germany.[60] Russia's total box-office revenue in 2007 was $565 million, up 37% from the previous year[61] (by comparison, in 1996 revenues stood at $6 million).[60] Russian cinema continues to receive international recognition. Russian Ark (2002) was the first feature film ever to be shot in a single take.

Animation

[edit | edit source]Russia also has a long and rich tradition of animation, which started already in the late Russian Empire times. Most of Russia's cartoon production for cinema and television was created during Soviet times, when Soyuzmultfilm studio was the largest animation producer. Soviet animators developed a great and unmatched variety of pioneering techniques and aesthetic styles, with prominent directors including Ivan Ivanov-Vano, Fyodor Khitruk and Aleksandr Tatarskiy. Soviet cartoons are still a source for many popular catch phrases, while such cartoon heroes as Russian-style Winnie-the-Pooh, cute little Cheburashka, Wolf and Hare from Nu, Pogodi! being iconic images in Russia and many surrounding countries. The traditions of Soviet animation were developed in the past decade by such directors as Aleksandr Petrov and studios like Melnitsa, along with Ivan Maximov.

Science and technology

[edit | edit source]Radio and TV

[edit | edit source]Russia was among the first countries to introduce radio and television. Due to the enormous size of the country Russia leads in the number of TV broadcast stations and repeaters. There were few channels in the Soviet time, but in the past two decades many new state-run and private-owned radio stations and TV channels appeared. In 2005 a state-run English language Russia Today TV started broadcasting, and its Arabic version Rusiya Al-Yaum was launched in 2007.

Internet

[edit | edit source]

Originating from Russian scientific community and telecommunication industries, a specific Russian culture of using the Internet has been established since the early 1990s. In the second half of the 1990s, the term Runet was coined to call the segment of Internet written or understood in the Russian language. Whereas the Internet "has no boundaries", "Russian Internet" (online communications in the Russian language) can not be localized solely to the users residing in the Russian Federation as it includes Russian-speaking people from all around the world. This segment includes millions of users in other ex-USSR countries, Israel and others abroad diasporas.[62]

With the introduction of the Web, many social and cultural events found reflections within the Russian Internet society. Various online communities formed, and the most popular one grew out of the Russian-speaking users of the California-based blogging platform LiveJournal (which was completely bought out in December 2007 by Russian firm SUP Fabrik).[63] In January 2008 a LiveJournal blog of the "3rd statesman" Sergey Mironov had appeared and he was shortly followed by the new President Dmitry Medvedev who opened a personal video blog which was later also expanded with a LiveJournal version.

As of late, there are scores of websites offering Russian language content including mass media, e-commerce, search engines and so on. Particularly notorious are the "Russian Hackers".[64] Russian web design studios, software and web-hosting enterprises offer a variety of services, and the results form a sort of national digital culture. E-commerce giants such as Google and Microsoft have their Russian branches. In September 2007, the national domain .ru passed the milestone of a million domain names.[65] By the end of the 2000s, VKontakte social network became the most populated in the Runet.

Science and innovation

[edit | edit source]

At the start of the 18th century the reforms of Peter the Great (the founder of Russian Academy of Sciences and Saint Petersburg State University) and the work of such champions as polymath Mikhail Lomonosov (the founder of Moscow State University) gave a great boost for development of science, engineering and innovation in Russia. In the 19th and 20th centuries Russia produced a large number of great scientists and inventors.

Nikolai Lobachevsky, a Copernicus of Geometry, developed the non-Euclidean geometry. Dmitry Mendeleev invented the Periodic table, the main framework of the modern chemistry. Nikolay Benardos introduced the arc welding, further developed by Nikolay Slavyanov, Konstantin Khrenov and other Russian engineers. Gleb Kotelnikov invented the knapsack parachute, while Evgeniy Chertovsky introduced the pressure suit. Pavel Yablochkov and Alexander Lodygin were great pioneers of electrical engineering and inventors of early electric lamps.

Alexander Popov was among the inventors of radio, while Nikolai Basov and Alexander Prokhorov were co-inventors of lasers and masers. Igor Tamm, Andrei Sakharov and Lev Artsimovich developed the idea of tokamak for controlled nuclear fusion and created its first prototype, which finally led to the modern ITER project. Many famous Russian scientists and inventors were émigrés, like Igor Sikorsky and Vladimir Zworykin, and many foreign ones worked in Russia for a long time, like Leonard Euler and Alfred Nobel.

The greatest Russian successes are in the field of space technology and space exploration. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was the father of theoretical astronautics.[66] His works had inspired leading Soviet rocket engineers such as Sergei Korolev, Valentin Glushko, and many others that contributed to the success of the Soviet space program at early stages of the Space Race and beyond.

In 1957 the first Earth-orbiting artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched; in 1961 on 12 April the first human trip into space was successfully made by Yury Gagarin; and many other Soviet and Russian space exploration records ensued, including the first spacewalk performed by Alexei Leonov, the first space exploration rover Lunokhod-1 and the first space station Salyut 1. Nowadays Russia is the largest satellite launcher[67][68] and the only provider of transport for space tourism services.

Other technologies, where Russia historically leads, include nuclear technology, aircraft production and arms industry. The creation of the first nuclear power plant along with the first nuclear reactors for submarines and surface ships was directed by Igor Kurchatov. NS Lenin was the world's first nuclear-powered surface ship as well as the first nuclear-powered civilian vessel, and NS Arktika became the first surface ship to reach the North Pole.

A number of prominent Soviet aerospace engineers, inspired by the theoretical works of Nikolai Zhukovsky, supervised the creation of many dozens of models of military and civilian aircraft and founded a number of KBs (Construction Bureaus) that now constitute the bulk of Russian United Aircraft Corporation. Famous Russian airplanes include the first supersonic passenger jet Tupolev Tu-144 by Alexei Tupolev, MiG fighter aircraft series by Artem Mikoyan and Mikhail Gurevich, and Su series by Pavel Sukhoi and his followers. MiG-15 is the world's most produced jet aircraft in history, while MiG-21 is most produced supersonic aircraft. During World War II era Bereznyak-Isayev BI-1 was introduced as the first rocket-powered fighter aircraft, and Ilyushin Il-2 bomber became the most produced military aircraft in history. Polikarpov Po-2 Kukuruznik is the world's most produced biplane, and Mil Mi-8 is the most produced helicopter.

Famous Russian battle tanks include T-34, the best tank design of World War II,[69] and further tanks of T-series, including T-54/55, the most produced tank in history,[70] first fully gas turbine tank T-80 and the most modern Russian tank T-90. The AK-47 and AK-74 by Mikhail Kalashnikov constitute the most widely used type of assault rifle throughout the world – so much so that more AK-type rifles have been produced than all other assault rifles combined.[71][72] With these and other weapons Russia for a long time has been among the world's top suppliers of arms.

| Lomonosov (1711–1765) |

Lobachevsky (1792–1856) |

Mendeleev (1837–1906) |

Mechnikov (1845–1916) |

I. Pavlov (1849–1936) |

Korolyov (1907–1966) |

Sakharov (1921–1989) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lifestyle

[edit | edit source]Ethnic dress of Russian people

[edit | edit source]

Not only the minorities in Russia but the Russian culture as a whole has in the different regions of the country like in Northwest Russia, Central Russia, Southern Russia, Siberian Russia, Volga Russia, Ural Russia, Far East Russia and the Russian North Caucasus and their Oblasts own local traditions and characteristics which were developed over a long period of time through strong ethno-cultural interactions within the various groups and communities, like Slavs, Tatars and Finno-Ugrics.[73]

Traditional Russian clothes include kaftan, a cloth which Old Russia had in common with similar robes in the Ottoman Empire, Scandinavia and Persia.[74] Kosovorotka, which was over a long time of period a traditional holidays blouse worn by men.[75] Ushanka for men, which design was influenced in 17th century when in central and northern Russia a hat with earflaps called treukh was worn. Sarafan which is connected to the Middle East region and were worn in Central- and Northern regions of Old Russia. In Southern Russia burka and papaha are connected to the Cossacks which, in turn, is culturally connected to the people of the Northern Caucaus. Kokoshnik for women was primarily worn in the northern regions of Russia in the 16th to 19th centuries. Lapti and similar shoes were mostly worn by poorer members in Old Russia and northern regions were Slavic, Baltic and Finno-Ugric people lived. Valenki are traditional Russian shoes from 18th century designs which originally originated in the Great steppe, from Asian nomads.[citation needed] Russian traditional cloths and its elements still have a high priority in today's Russia, especially in pagan Slavic communities, folk festivals, Cossack communities, in modern fashion and Russian music ensembles.

Cuisine

[edit | edit source]

Russian cuisine widely uses fish, poultry, mushrooms, berries, and honey. Crops of rye, wheat, barley, and millet provide the ingredients for a plethora of breads, pancakes, cereals, kvass, beer, and vodka. Black bread is relatively more popular in Russia compared to the rest of the world. Soups, stews and filled dumplings are very characteristic for Russian cuisine. The most popular soups include shchi, borsch, ukha, solyanka and okroshka. Smetana (a heavy sour cream) is often added to soups and salads. Most popular dumplings are pirozhki, pelmeni, varenyky and Turkic manti. One of the most popular are foods are blini, which are like syrniki native types of Russian pancakes. Furthermore, Cutlets (like Chicken Kiev) and shashlyk are popular meat dishes, the last one being of Tatar and Caucasus.[citation needed] origin respectively. Popular salads include Russian Salad, vinaigrette and Dressed Herring. One of the main characteristics of Russian food culture are Zakuski, which define a Russian-laid table.

Traditions

[edit | edit source]Holidays

[edit | edit source]

There are eight public holidays in Russia. The New Year is the first in calendar and in popularity. Russian New Year traditions resemble those of the Western Christmas, with New Year Trees and gifts, and Ded Moroz (Father Frost) playing the same role as Santa Claus. Rozhdestvo (Orthodox Christmas) falls on 7 January, because Russian Orthodox Church still follows the Julian (old style) calendar and all Orthodox holidays are 13 days after Catholic ones. Another two major Christian holidays are Paskha (Easter) and Troitsa (Trinity), but there is no need to recognize them as public holidays since they are always celebrated on Sunday.

Further Russian public holidays include Defender of the Fatherland Day (23 February), which honors Russian men, especially those serving in the army; International Women's Day (8 March), which combines the traditions of Mother's Day and Valentine's Day; International Workers' Day (1 May), now renamed Spring and Labor Day; Victory Day (9 May); Russia Day (12 June); and Unity Day (4 November), commemorating the popular uprising which expelled the Polish-Lithuanian occupation force from Moscow in 1612. The latter is a replacement for the old Soviet holiday celebrating October Revolution of 1917 (again, it was falling on November because of the difference of calendars). Fireworks and outdoor concerts are common features of all Russian public holidays.

Victory Day is the second popular holiday in Russia, it commemorates the victory over Nazi Germany in World War II and is widely celebrated throughout Russia. A huge military parade, hosted by the President of the Russian Federation, is annually organized in Moscow on Red Square. Similar parades are organized in all major Russian cities and the cities with the status Hero city or City of Military Glory.

Other popular holidays, which are not public, include Old New Year (New Year according to Julian Calendar on 1 January), Tatiana Day (day of Russian students on 25 January), Maslenitsa (an old pagan holiday a week before the Great Lent), Cosmonautics Day (a day of Yury Gagarin's first ever human trip into space on 12 April), Ivan Kupala Day (another pagan Slavic holiday on 7 July) and Peter and Fevronia Day (taking place on 8 July and being the Russian analogue of Valentine's Day, which focuses, however, on the family love and fidelity). On different days in June there are major celebrations of the end of the school year, when graduates from schools and universities traditionally swim in the city fountains; the local varieties of these public events include Scarlet Sails tradition in Saint Petersburg.

Religion

[edit | edit source]

Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism are Russia's traditional religions, deemed part of Russia's "historical heritage" in a law passed in 1997.[76] Estimates of believers widely fluctuate among sources, and some reports put the number of non-believers in Russia as high as 16–48% of the population.[77] Russian Orthodoxy is the dominant religion in Russia.[78] 95% of the registered Orthodox parishes belong to the Russian Orthodox Church while there are a number of smaller Orthodox Churches.[79] However, the vast majority of Orthodox believers do not attend church on a regular basis. Nonetheless, the church is widely respected by both believers and nonbelievers, who see it as a symbol of Russian heritage and culture.[80] Smaller Christian denominations such as Roman Catholics, Armenian Gregorians, and various Protestants exist.

The ancestors of many of today's Russians adopted Orthodox Christianity in the 10th century.[80] The 2007 International Religious Freedom Report published by the US Department of State said that approximately 100 million citizens consider themselves Russian Orthodox Christians.[81] According to a poll by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center, 63% of respondents considered themselves Russian Orthodox, 6% of respondents considered themselves Muslim and less than 1% considered themselves either Buddhist, Catholic, Protestant or Jewish. Another 12% said they believe in God, but did not practice any religion, and 16% said they are non-believers.[82]

Cossack culture in Russia

[edit | edit source]

The steppe culture of the Russian Cossacks originated from nomadic steppe people which merged with Eastern Slavic people groups into large communities. The early Cossack communities emerged in the 14th century, the first, among others, were the Don Cossacks. Other Cossack communities that have played an important role in Russia's history and culture are the Ural Cossacks, Terek Cossacks, Kuban Cossacks, Orenburg Cossacks, Volga Cossacks, Astrakhan Cossacks, Siberian Cossacks, Transbaikal Cossacks, Amur Cossacks, Ussuri Cossacks. Cossacks defended the Russian borders and expanded Russia's territory. The regions of the large Cossack communities enjoyed many freedoms in Tsarist Russia. The culture of the Cossacks became an important part of Russian culture, many Russian songs and various elements in dances and Russias culture in general were much shaped by the Cossack communities.[83]

Russian forest culture

[edit | edit source]The forest plays a very important role in Russia's more than 1000-year-old culture and history. The forest had a great influence on the characteristics of Russian people and their cultural creations. Many myths of Russian culture are closely intertwined with the forest. Various of the early Slavic and other tribes built their houses out of wood so that the forest influenced the style of Russian architecture significantly. The handcraft Hohloma which originated in the Volga region is made out of wood and depicts numerous plants of the forest, like the berry Viburnum opulus (Russian: Калина, Kalina), flowers and leaves. Many Russian fairy tales play in the forest and fictional characters like Baba Yaga are strongly connected to Russian wood culture. The forest is also an important subject of many Russian folk songs.[84][85][86]

More elements of Russian society and culture

[edit | edit source]Russian walking culture

Strolling or walking (Russian: гулять, gulyat') is very common in the Russian society. In contrast to many western countries strolling is very common among young people in Russia. Young people often arrange just to go for a walk.[87][88] Besides the verb, the experience itself, which describes the time span of the walk, is called progulka (Russian: прогулка).[89] Walking is so important in Russian culture that gulyat' is also a synonym for "to party".[90][91]

Mushroom hunting and berry picking

Activities in the forest where people pick mushrooms and berries are very common in Russia. Mushrooms (Russian: грибы, griby) have been an important part of Russian folk culture at least since the 10th century and an essential part of Russian meals. There are more than 200 kinds of edible mushrooms in Russia. Mushrooms were always considered magical and so they play a prominent role in Russian fairy tales. The ability to identify and prepare edible mushrooms is often passed on from generation to generation. The mushroom hunting tradition is especially common in Slavic-speaking and Baltic countries. The berry (Russian: ягода, yagoda) also plays an important role in Russian folk culture and is often part of Russian craftsmanship, folk songs and national costumes. The cranberry was known in Europe for centuries as the "Russian berry". To pick mushrooms and berries in forests is a kind of meditation in Russia.[92][93][94][95][96]

Sports

[edit | edit source]Russians have been successful at a number of sports and consistently finish in the top rankings at the Olympic Games and in other international competitions. Combining the total medals of Soviet Union and Russia, the country is second among all nations by number of gold medals both at the Summer Olympics and at the Winter Olympics.

During the Soviet era, the national Olympic team placed first in the total number of medals won at 14 of its 18 appearances; with these performances, the USSR was the dominant Olympic power of its era. Since the 1952 Olympic Games, Soviet and later Russian athletes have always been in the top three for the number of gold medals collected at the Summer Olympics.

Soviet gymnasts, track-and-field athletes, weight lifters, wrestlers, boxers, fencers, shooters, chess players, cross country skiers, biathletes, speed skaters and figure skaters were consistently among the best in the world, along with Soviet basketball, handball, volleyball and ice hockey players. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian athletes have continued to dominate international competitions. The 1980 Summer Olympic Games were held in Moscow while the 2014 Winter Olympics and the 2014 Winter Paralympics were hosted by Sochi.

Soviet Union dominated the sport of gymnastics for many years, with such athletes as Larisa Latynina, who, until 2012, held a record of most Olympic medals won per person and most gold Olympic medals won by a woman. Today, Russia is leading in rhythmic gymnastics with such stars as Alina Kabaeva, Irina Tschaschina and Yevgeniya Kanayeva.

Russian synchronized swimming is the best in the world, with almost all gold medals having been swept by Russians at Olympics and World Championships for more than a decade. Figure skating is another popular sport in Russia; in the 1960s, the Soviet Union rose to become a dominant power in figure skating, especially in pair skating and ice dancing, and at every Winter Olympics from 1964 until 2006, a Soviet or Russian pair has won gold, often considered the longest winning streak in modern sports history. Since the end of the Soviet era, tennis has grown in popularity and Russia has produced a number of famous tennis players. Chess is also a widely popular pastime; from 1927, Soviet and Russian chess grandmasters have held the world championship almost continuously.

Basketball

[edit | edit source]As the Soviet Union, Russia was traditionally very strong in basketball, winning Olympic tournaments, World Championships and Eurobasket. As of 2009 they have various players in the NBA, notably Utah Jazz forward Andrei Kirilenko, and are considered as a worldwide basketball force. In 2007, Russia defeated world champions Spain to win Eurobasket 2007. Russian basketball clubs such as PBC CSKA Moscow (numerous Euroleague Champions) have also had great success in European competitions such as the Euroleague and the ULEB Cup.

Ice hockey

[edit | edit source]Although ice hockey was only introduced during the Soviet era, the national team soon dominated the sport internationally, winning gold at seven of the nine Olympics and 19 of the 30 World Championships they contested between 1954 and 1991. Russian players Valeri Kharlamov, Sergei Makarov, Viacheslav Fetisov and Vladislav Tretiak hold four of the six positions on the IIHF Team of the Century.[98] As with some other sports, the Russian ice hockey programme suffered after the breakup of the Soviet Union, with Russia enduring a 15-year gold medal drought. At that time many prominent Russian players made their careers in the National Hockey League (NHL). In recent years Russia has reemerged as a hockey power, winning back to back gold medals in the 2008 and 2009 World Championships, and overtaking Team Canada as the top ranked ice hockey team in the world, but then lost to Canada in the quarter-finals of the 2010 Olympics and 2010 World Junior Championship.[99] The Kontinental Hockey League (KHL) was founded in 2008 as a rival of the NHL.

Bandy

[edit | edit source]Bandy, known in Russian as "hockey with a ball" and sometimes informally as "Russian hockey" (as opposed to "Canadian hockey", an informal name for ice hockey), is another traditionally popular ice sport, with national league games averaging around 3,500 spectators.[100] It's considered a national sport. The Soviet Union national bandy team won all the Bandy World Championships from 1957 to 1979. The Russian team is the reigning world champion since the 2014 tournament, having defended the title in 2015.

Football

[edit | edit source]

During the Soviet period, Russia was also a competitive footballing nation. Despite having legendary players such as goalkeeper of the century Lev Yashin, the USSR never really managed to assert itself as one of the major forces of international football, although its teams won various championships (such as Euro 1960) and reached numerous finals (such as Euro 1988). Along with ice hockey and basketball, football is one of the most popular sports in modern Russia. In recent years, Russian football, which downgraded in 1990-s, has experienced a revival. Russian clubs (such as CSKA Moscow, Zenit St Petersburg, Lokomotiv Moscow, and Spartak Moscow) are becoming increasingly successful on the European stage (CSKA and Zenit winning the UEFA Cup in 2005 and 2008 respectively). The Russian national football team reached the semi-finals of Euro 2008, losing only to eventual champions Spain. The nation also hosted the 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup as well as the 2018 FIFA World Cup at which the national team lost in the Quarterfinals 4–2 on penalty kicks to Croatia, their best ever finish as an independent nation.

Martial arts

[edit | edit source]Russia has an extensive history of martial arts. Some of its best-known forms include the fistfight, Sambo, and Systema with its derivatives Ryabko's Systema and Retuinskih's System ROSS. Undefeated lightweight UFC champion Khabib Nurmagomedov is from Makhachkala and was called by President Vladimir Putin following his victory over Conor McGregor.

National symbols

[edit | edit source]State symbols

[edit | edit source]State symbols of Russia include the Byzantine double-headed eagle, combined with St. George of Moscow in the Russian coat of arms; these symbols date from the time of the Grand Duchy of Moscow. The Russian flag appeared in the late Tsardom of Russia period and became widely used during the era of the Russian Empire. The current Russian national anthem shares its music with the Soviet Anthem, though not the lyrics (many Russians of older generations don't know the new lyrics and sing the old ones). The Russian imperial motto God is with us and the Soviet motto Proletarians of all countries, unite! are now obsolete and no new motto has been officially introduced to replace them. The Hammer and sickle and the full Soviet coat of arms are still widely seen in Russian cities as a part of old architectural decorations. Soviet Red Stars are also encountered, often on military equipment and war memorials. The Soviet Red Banner is still honored, especially the Banner of Victory of 1945.

Unofficial symbols

[edit | edit source]The Matryoshka doll is a recognizable symbol of Russia, while the towers of Moscow Kremlin and Saint Basil's Cathedral in Moscow are main Russia's architectural symbols. Cheburashka is a mascot of Russian national Olympic team. Mary, Saint Nicholas, Saint Andrew, Saint George, Saint Alexander Nevsky, Saint Sergius of Radonezh, Saint Seraphim of Sarov are Russia's patron saints. Chamomile is a flower that Russians often associate with their Motherland, while birch is a national tree. The Russian bear is an animal often associated with Russia, though this image has Western origins and Russians themselves do not consider it as a special symbol. The native Russian national personification is "Родина мать" Mother Motherland (the statue of it located on the Mamay hill "Мамаев курган" in Volgograd /former Stalingrad/), called Mother Russia at the West.

Tourism

[edit | edit source]Tourism in Russia has seen rapid growth since the late Soviet times, first inner tourism and then international tourism as well. Rich cultural heritage and great natural variety place Russia among the most popular tourist destinations in the world. The country contains 29 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, while many more are on UNESCO's tentative lists.[101] Major tourist routes in Russia include a travel around the Golden Ring of ancient cities, cruises on the big rivers like Volga, and long journeys on the famous Trans-Siberian Railway. Diverse regions and ethnic cultures of Russia offer many different food and souvenirs, and show a great variety of traditions, like Russian banya, Tatar Sabantuy, or Siberian shamanist rituals.

Cultural tourism

[edit | edit source]

Most popular tourist destinations in Russia are Moscow and Saint Petersburg, the current and the former capitals of the country and great cultural centers, recognized as World Cities. Moscow and Saint Petersburg feature such world-renowned museums as Tretyakov Gallery and Hermitage, famous theaters like Bolshoi and Mariinsky, ornate churches like Saint Basil's Cathedral, Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, Saint Isaac's Cathedral and Church of the Savior on Blood, impressive fortifications like Moscow Kremlin and Peter and Paul Fortress, beautiful squares like Red Square and Palace Square, and streets like Tverskaya and Nevsky Prospect. Rich palaces and parks of extreme beauty are found in the former imperial residences in suburbs of Moscow (Kolomenskoye, Tsaritsyno) and Saint Petersburg (Peterhof, Strelna, Oranienbaum, Gatchina, Pavlovsk Palace, Tsarskoye Selo). Moscow contains a great variety of impressive Soviet-era buildings along with modern skyscrapers, while Saint Petersburg, nicknamed Venice of the North, boasts of its classical architecture, many rivers, channels and bridges.

Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan, shows a unique mix of Christian Russian and Muslim Tatar cultures. The city has registered a brand The Third Capital of Russia, though a number of other major Russian cities compete for this status, like Novosibirsk, Yekaterinburg and Nizhny Novgorod, all being major cultural centers with rich history and prominent architecture. Veliky Novgorod, Pskov and the cities of Golden Ring (Vladimir, Yaroslavl, Kostroma and others) have at best preserved the architecture and the spirit of ancient and medieval Rus', and also are among the main tourist destinations. Many old fortifications (typically Kremlins), monasteries and churches are scattered throughout Russia, forming its unique cultural landscape both in big cities and in remote areas.

Resorts and nature tourism

[edit | edit source]

The warm subtropical Black Sea coast of Russia is the site for a number of popular sea resorts, like Sochi, known for its beaches and wonderful nature. At the same time Sochi can boast a number of major ski resorts, like Krasnaya Polyana; the city is the host of 2014 Winter Olympics and the 2014 Winter Paralympics. The mountains of the Northern Caucasus contain many other popular ski resorts, like Dombay in Karachay–Cherkessia.

The most famous natural tourist destination in Russia is Lake Baikal, named the Blue Eye of Siberia. This unique lake, oldest and deepest in the world, has crystal-clean waters and is surrounded by taiga-covered mountains.

Other popular natural destinations include Kamchatka with its volcanoes and geysers, Karelia with its many lakes and granite rocks, Altai with its snowy mountains and Tyva with its wild steppes.

Timeline

[edit | edit source]- 1801–1914: Upper classes in Russia spoke French, some even as their first language, which became a problem during Napoleon's invasion; the Golden Age of Russian poetry and Russian literature; Pushkin & Lermontov.

- early 20th century: Silver Age of Russian literature

- 1917–1932: Constructivism. The Gesher Theater in Israel was founded by Russian emigres to bring Russian theatrical traditions to the Israeli public.[102]

- 1932–1953: Stalinist period characterized by Socialist realism

- 1953–1991: With the death of Joseph Stalin, there was a new sense of optimism in the Soviet Union with a brief flowering of a more liberal, open culture.

- 1991–present: The Culture of Russia includes Culture of the Soviet Union, Culture of Russia, Russian humour

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b "Russia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

The inhabitants of Russia are quite diverse. Most are ethnic Russians, but there also are more than 120 other ethnic groups present, speaking many languages and following disparate religious and cultural traditions. [...] Russia can boast a long tradition of excellence in every aspect of the arts and sciences.

- ↑ a b Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. "Russian Literature". Russian Literature. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761564269/Russian_Literature.html. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ↑ Compare: Alekseev, Alexander (2015-10-23). "Russia's 5 greatest folk song and dance ensembles" (in en-US). https://www.rbth.com/arts/events/2015/10/23/rusias-5-greatest-folk-song-and-dance-ensembles_533363. "Folk ensembles from Russia tour around the world with great success."

- ↑ a b "Russia::Music". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ↑ a b "A Tale of Two Operas". Petersburg City. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ↑ a b Garafola, L (1989). Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Oxford University Press. p. 576. ISBN 0-19-505701-5.

- ↑ a b c "Russia::Motion pictures". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- ↑ "The_Byzantine_Influence_on_Russia".

- ↑ "The Steppe Tradition Settles Down", The Steppe Tradition in International Relations, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 175–178, doi:10.1017/9781108355308.006, ISBN 9781108355308

- ↑ https://www.whiteplainspublicschools.org/cms/lib/NY01000029/Centricity/Domain/353/The_Byzantine_Influence_on_Russia_(35).doc

- ↑ Maximick, Katherine. "Steppe Nomads and Russian Identity: The (In)Visibility of Scythians, Mongols and Cossacks in Russian History and Memory" (PDF).

- ↑ excerpted from Glenn E. Curtis (ed.) (1998). "Russia: A Country Study: Kievan Rus' and Mongol Periods". Washington, DC: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ↑ Kamalakaran, Ajay (2014-08-05). "Asia or Europe? How about both?". www.rbth.com. Retrieved 2019-03-08.