Wikijunior:United States Charters of Freedom/History of the Charters of Freedom

In 1952, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution came to join the Bill of Rights (which was placed in 1938) at the National Archives. In fact, the documents did not receive the name "Charters of Freedom" until 1953. Where were the Charters of Freedom before then? This article will tell you about their history.

History of the Declaration of Independence (1776-1921)

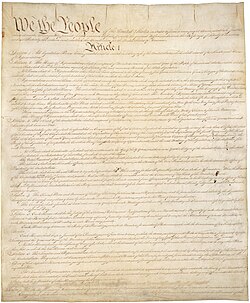

[edit | edit source]On July 19, 1776, Congress resolved "that the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of "The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America," and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress. Timothy Matlack, an assistant to Charles Thomson, the secretary of the Continental Congress, did the engrossing (calligraphy with large letters) on a single sheet of parchment. On August 2, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was signed by the delegates.

The Declaration of Independence, probably rolled up like other parchment documents of the time, moved with Congress from city to city throughout the Revolutionary War. Each time the document was used, it would have been unrolled and re-rolled.

In September 1789 the Secretary of Congress transferred the Declaration to the custody of the Secretary of State, and then it moved with the national government, from New York to Philadelphia and then in 1800 to Washington, D.C..

In 1814, when the British attacked Washington, D.C., the Declaration of Independence was evacuated, first to an unused gristmill near Chain Bridge over the Potomac River and later to a private home near Leesburg, Virginia. By 1817, the Secretary of State Richard Rush noted that the "hand of time" had faded the signatures.

In 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams contracted with William J. Stone to engrave a facsimile of the Declaration, it was completed in 1823. It is because of Stone's engraving plate, now in the National Archives, that we know what the Declaration of Independence looked like.

In 1841, when the new Patent Office building opened (now the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery at Seventh and F Streets, NW), Secretary of State Daniel Webster sent the Declaration of Independence and other interesting documents (such as General Washington's commission in the Revolutionary Army) to be exhibited for public viewing, and it remained there, exposed to natural light, for thirty-five years. During its stay at the Patent Office, the combined effects of aging, sunlight, and fluctuating temperature and relative humidity took their toll on the document, and observers remarked on its worn and faded appearance.

The Declaration of Independence was exhibited at Independence Hall in Philadelphia for exhibit at the Centennial National Exposition in 1876, and when it returned to Washington, D.C. in 1877, it was placed on exhibit at the new State-War-Navy Building (now the Eisenhower Executive Office Building) next to the White House.

In 1892, a new steel case was constructed, and plans were made to send it to Chicago for the World's Columbian Exposition, but at the last minute it was decided that due to the fading of the text and the deterioration of the parchment, the Declaration of Independence could no longer be safely exhibited and the plans were cancelled. The Declaration was carefully wrapped and stored flat in the State Department library until 1921.

History of the Constitution (1787-1921)

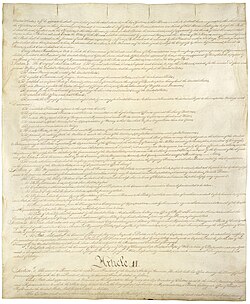

[edit | edit source]The Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787, and on September 16-17, 1787, Jacob Shallus, an assistant clerk of the Pennsylvania State Assembly, engrossed the Constitution on four sheets of parchment. Delegates signed it on page four. The Constitution, like the Declaration, passed to the custody of the Department of State in 1789, moved with the government, and was evacuated to Leesburg in 1814. The Constitution was never exhibited, and there are only a few mentions of it in the historical records.

|

|

|

|

History of the Bill of Rights (1789-1951)

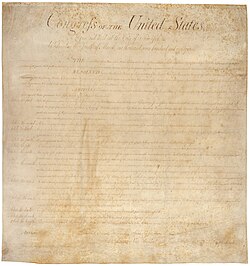

[edit | edit source]The joint resolution of Congress proposing twelve amendments to the Constitution, like the laws of the first Congress, was engrossed on a single sheet of parchment by a congressional clerk, William Lambert, in September 1789. The Speaker of the House, Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg, and the president of the Senate, John Adams, signed it. By 1791 three-fourths of the states had ratified articles three through twelve, and they became the first ten amendments, the Bill of Rights.

Unfortunately, practically nothing is known about the Bill of Rights between 1789 and 1938, except that it was kept with other signed original laws and resolutions, moved with the government, and although not specifically mentioned, was probably evacuated to Leesburg in 1814.

In 1938, the State Department transferred the original laws and resolutions of Congress, including constitutional amendments, to the National Archives. The first known photograph of the Bill of Rights was made to illustrate the National Archives annual report in 1941. From September 1947 to January 1949, the Bill of Rights was the featured document on the tour of the Freedom Train, which carried 126 historic documents to 322 cities. The Bill of Rights was on exhibit in the National Archives Building from September 1949 to January 1951. During the Korean War, the Bill of Rights and other documents of high intrinsic value were sent to the Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York.

History of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution (1921-1952)

[edit | edit source]From 1921 to 1952 the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution share a common history. In 1920 a committee of scholars investigated and made recommendations for the permanent preservation and possible exhibition of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. A year later, President Warren Harding signed an executive order transferring custody of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution from the State Department to the Library of Congress. The next day, the Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, went to the State Department, signed a receipt, placed the Declaration and Constitution on a pile of leather mail sacks and a cushion in a Ford Model-T truck, returned with them to the Library of Congress, and placed them in a safe in his office. Putnam asked Congress for a special appropriation to create a dignified exhibit so that visitors to Washington could view the documents in a "sort of shrine." Congress gave him twelve thousand dollars, and the new exhibit opened in 1924. For the first time the Constitution was placed on exhibit, next to the Declaration of Independence. Newspapers reported that after almost 150 years of traveling the two great documents had finally found a permanent home.

In 1926, Congress made its first appropriation for a National Archives Building. At the laying of the cornerstone on February 20, 1933, President Herbert Hoover announced that "the most sacred documents of our history— the originals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States" would be placed on display there. Later that year, architect John Russell Pope selected Barry Faulkner to paint two large murals for the Exhibition Hall, the subjects of which were the signing of those two great documents. The murals depict Thomas Jefferson presenting the Declaration of Independence to John Hancock and James Madison presenting the final draft of the Constitution to George Washington.

In 1934 President Franklin Roosevelt selected the first Archivist of the United States, R.D.W. Connor, and they both believed the Declaration and Constitution belonged in the new National Archives Building. When reporters asked, Connor declined comment but gave reporters a copy of Hoover's speech. Librarian Putnam declared that President Hoover "made a mistake." The two great documents were at the Library of Congress by executive order of the President and an act of Congress (the appropriation to build the exhibit), and they would remain there in their shrine instead of moving to the "lobby" of the National Archives Building. Connor was furious, but he remained silent. He owed his job to the recommendation of J. Franklin Jameson, chief of the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, and Connor had promised Jameson he would not take the initiative in seeking the transfer of the documents. Ironically, it was Jameson, the dean of American historians, who suggested the people to be included in the Faulkner's two great murals and approved his sketches. Privately, Connor talked to President Roosevelt several times about transferring the documents to the National Archives, but they agreed it would be best to wait until Putnam left the scene.

Then, World War II intervened. In December 1941, the Library of Congress sent the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to the bullion depository at Fort Knox, Kentucky, for safekeeping. By September 1944, it was decided to return the documents to their permanent exhibit at the shrine in the Library of Congress. The new Archivist of the United States, Solon Buck, had no intention of pressing for their transfer to the National Archives.

The Charters of Freedom at the National Archives (1951-present)

[edit | edit source]On September 17, 1951, there was a grand ceremony at the Library of Congress for the reopening of a permanent encasement for the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, newly sealed in helium by the Bureau of Standards. The distinguished guests included President Truman, the new Librarian of Congress, Luther Evans, and the new Archivist of the United States, Wayne Grover.

President Truman admitted that preserving the parchments might prove difficult, but the ideas in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States would never perish and they would continue to give energy and hope to new generations in the United States and in other countries. Truman also said the first ten amendments, the Bill of Rights, were just as fundamental a part of our basic law.

Truman then added a sentence, in his handwriting, to the reading copy of his speech: "I hope these first ten amendments will be sealed up and placed alongside the original document. They are just as important."

While delivering his speech Truman slightly changed his own sentence. He said he hoped "the first ten amendments will be put on parchment and sealed up." And the Bill of Rights was not "just as important," but "the most important part of the Constitution."

A few weeks later, Wayne Grover and Luther Evans met for lunch and together hatched the plot to fulfill President Truman's request— to seal the Bill of Rights in helium and exhibit it alongside the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution in the National Archives Building.

Working together secretly, they agreed it would be necessary to formally clear the transfer with the President, congressional leaders, and Senator Theodore Green, the chairman of the Joint Committee on the Library. All favored the transfer. On April 30, 1952, Evans provided the agenda for the committee meeting, with the second item being "Transfer of certain documents to the National Archives." Evans went to the meeting alone because he knew that some of his colleagues at the library were hostile, and he wanted the committee not just to approve but to order him to transfer the documents, which it did unanimously. That led to seven months of remodeling of the National Archives Exhibition Hall and planning for the transfer.

The ceremony leaving the library on Saturday, December 13, 1952, was a spectacular event. The commanding general of the Air Force Headquarters Command formally received the documents at the Library of Congress at 11 a.m. Twelve members of the Armed Forces Special Police carried the five parchment pages, encased in helium-filled glass cases and enclosed in wooden crates, through a cordon of eighty-eight servicewomen down the library steps. The boxes were placed on mattresses in an armored Marine Corps personnel carrier. A color guard, ceremonial troops, the Army Band, the Air Force Drum and Bugle Corps, two light tanks, four servicemen carrying submachine guns, and a motorcycle escort paraded down Pennsylvania and Constitution Avenues to the Archives Building. Both sides of the street along the parade route were lined by Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Marine, and Air Force personnel. The general and the twelve special policemen arrived at the National Archives Building at 11:35 a.m., carried the crates up the steps, and formally delivered them into the custody of the Archivist of the United States.

Two days later, at 10:15 a.m., on Monday, December 15, 1952, the formal enshrining ceremony was equally impressive. Officials of more than one hundred national civic, patriotic, religious, veterans, educational, business, and labor groups crowded into the Exhibition Hall. The chief justice of the United States presided. After the invocation by the chaplain of the Senate, the governor of Delaware (the first state to ratify the Constitution) called the roll of states in the order in which they ratified the Constitution or were admitted to the Union. As each state was called, a servicewoman carrying the state flag entered the Exhibition Hall and remained at attention in front of the display cases circling the hall. President Truman announced that "the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are now assembled in one place for display and safekeeping." Senator Green briefly traced the history of the three documents, and the Librarian of Congress and the Archivist of the United States jointly unveiled the shrine. Finally, Chief Justice Vinson spoke briefly; the chaplain of the House of Representatives gave the benediction; the United States Marine Corps Band played the Star-Spangled Banner; the President was escorted from the hall; the bearers of the flags of the forty-eight states (Alaska and Hawaii were not states yet.) marched out and the ceremony was over.

Thus opened the new exhibit for the three parchment documents, together for the first time in one place and with a new collective name never before used: "the Charters of Freedom." Where did that phrase come from? President Truman must be given credit for first expressing the idea in 1951 of exhibiting the Bill of Rights with the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. But the three documents did not become the Charters of Freedom until 1953, when the National Archives published "The Charters of Freedom", an exhibit catalog that included facsimile copies of all six parchment sheets.

In his speech, President Truman said "we are engaged here today in a symbolic act. We are enshrining these documents for future ages. . . . This magnificent hall has been constructed to exhibit them, and the vault beneath, that we have built to protect them, is as safe from destruction as anything that the wit of modern man can devise." Truman was right, but now the wit of modern man has devised something better— the new encasements, which will house the charters beginning September 17, 2003.

In these new encasements, the eighteenth century meets the twenty-first century. Sophisticated monitoring systems will allow conservators to periodically check the condition of the parchments, and the sealed cases will provide a stable environment. As the latest in the line of custodians of these documents, the National Archives and Records Administration is working to ensure that future generations will be able view them and be inspired by them.