User:PanosKratimenos/sandbox/BASC001/2020-21/Thursday11-12/Truth

Approaches to Truth

[edit | edit source]Ontology: Essentialist and Constructivist

[edit | edit source]Ontology, a branch of philosophy, refers to the nature of being.[1] It can be best defined by Norman Blaikie, an author and social researcher, when he says, “Ontological assumptions make claims about what kinds of social phenomena do or can exist, the conditions of their existence, and the ways in which they are related.”[2]

Although six or more specific classifications have been devised to understand ontological assumptions, individuals fall in one of the two broad categorisations: essentialist or constructionist.

Essentialist, or objective, ontology refers to the existence of social reality and its meaning independent of cognitive human perception and actions. In other words, it asserts that social phenomena exist objectively and independently of social perception. The meanings attached to tangible objects and intangible concepts are fixed/immutable, regardless of the context, circumstance or history.[2] This ideology is more prevalent in the natural sciences as they heavily emphasise empiricism as a valid method of theory determination.

Constructionist, or constructivist, ontology refers to social reality and its meaning being a construction of social perception. Meanings attached to tangible or intangible objects are inventions of social actors, cultures and societies, which continually evolve over time according to its context.[2] Social constructionists believe that truths regarding social phenomena is created rather than discovered. They reject the idea of a necessary congruence of "truth" and "reality". However, this does not mean that the construction of social concepts takes away from how they are real. Though they believe that societies produce and project a version of reality aligned with their own assumptions, the very understanding of the world and the subjective experience of daily life as a result of is what is known to constructionists as the truth; the tangible consequences of social phenomena make them an undeniable part of reality. [3] This ideology is more prevalent in social sciences, as they place a greater emphasis on human mind, behaviour, and society. For example, the connotations ascribed to being a woman differs across countries, culture and time. Women’s rights have continuously evolved, more in some cultures than others, leading to a different social definition, status and role in society.

Moreover, Greek philosopher Plato’s renown allegory of the cave illustrates that different perceptions of the same reality can co-exist. The allegory describes chained prisoners (since birth) in a cave facing a wall on which the fire nearby reflects the shadows of objects or people passing by. The prisoners ascribe names and meanings to these objects, which become their reality. Then, one of the prisoners sets free and goes out to observe the real world. He discovers that the shadows itself are not the objects, but mere reflections of them and that the tangible objects themselves are reality. This allegory as further expanded upon by Socrates, who asked that what if one told the prisoner that there was no substance in what he saw in the cave, but what is he looking at now is closer to reality, and so would the prisoner not be bewildered and think that there was more reality in what he saw before than what he is being shown now.[4]

This elucidates the fact that the prisoners inside the cave and the freed prisoner on the outside have their versions of the truth. Therefore, truth differs across cultural and social norms and environments, and depends on which theory of truth, as explained by various disciplines of academia, we subscribe to.[5] Essentialists would say that the identity of the objects remained the same even though their perceptions and meanings evolved. Constructivists would look at the same allegory and assert that the objects' identities lied solely in these individual perceptions, and as the interpretations evolved, the identities and meanings of these objects evolved alongside.

Philosophy: Idealism and Realism

[edit | edit source]Idealism and Realism are central to the discussion of philosophy, particularly in the branch of metaphysics. This is a branch of philosophy that is very difficult to be defined due to the different interpretations philosophers have over time [6], yet it is critical to the study of philosophy as it is first understood to be the study of the first cause. Both Idealism and Realism are valid means to truth but they yield different outcomes.

Idealism

[edit | edit source]Idealists argue that reality is inseparable to human experience and understanding [7], philosophers that represented this view include Berkeley and Kant. Therefore for idealists, reality is subjective to what an individual experiences and could be different to different people. However, within idealism there are also debates between subjective idealism and objective idealism.

Realism

[edit | edit source]Realists holds the following view [8]:

- a, b, and c and so on exist, and the fact that they exist and have properties such as F-ness, G-ness, and H-ness is (apart from mundane empirical dependencies of the sort sometimes encountered in everyday life) independent of anyone’s beliefs, linguistic practices, conceptual schemes, and so on.

This simply means that reality exists independent of human experience.

Idealism and Realism on Truth and Reality

[edit | edit source]Idealists and Realists provide a very different understanding towards the nature of reality. Realists hold a position of the reality holding an objective truth that exist in itself, whilst Idealists argue that this truth exists only through the lens of humans and it is not necessary the case that there is an objective truth. Nonetheless, for philosophers, it is crucial to first understand the nature of the subject before producing any knowledge claim about it, thus, a dilemma is present. In order to examine 'truth', one has to know what it is in the first place, but to know what it is one would use different means to approach it. Yet, the means one uses usually carries with it an assumption. Hence, whether or not one could truly understand what truth is, is perhaps unknown.

Phenomenological Approach to Truth

[edit | edit source]Phenomenology itself is a discipline that studies how information can differ from different points of view. A phenomenological approach to truth studies the information presented from experiences through perceptions and interpretations developed from the human consciousness. People access and perceive information and this perception is influenced by their individual past knowledge, past experiences, and unconscious biases. Interpretation of these perceptions occur through the choices and decisions people make by using their perceived knowledge and applying it as their behaviour and as developing an certainty for a choice.[9]

Truth in Gender

[edit | edit source]Truth of Gender From Different Perspectives

[edit | edit source]Truth and knowledge is popularly associated with factuality and objectivity. This is particularly true in disciplines under the umbrella of sciences - disciplines aiming to offer a better understanding and explanation of reality - which Sociology falls under as a social science. Certainty, objectivity and universality are often associated with the truth in the sciences, however, Sociology does not prioritise these aspects. [10] Instead, it concerns itself with investigating the production of truth in a social context. Sociology primarily re-examines widely accepted truths in societies from a new perspective. The research of Sociologists provide tools and data often used in furthering social justice;[11] the discipline is known to challenge and overturn many traditional conceptions that were previously held to be true (such as how the impoverished were poor due to laziness, or the idea that men were inherently more intelligent than women)[12] by exploring the process by which "truths" are constructed - rather than discovered - in societies.

This allows study in sociology to recognise and investigate different perspectives to arriving to truth. Broadly speaking, approaches can be separated into categories of practice and categories of analyses. Categories of practice refers to what is commonly recognised as truth in everyday life; it is developed by ordinary social actors (or what is commonly known to us as "ordinary people", considered as persons without significant positions of leadership in society) and the perspectives used by them to understand and explain the everyday experience of the world around them. [13][14]Categories of analysis on the other hand refers to what is considered truth by scientists and researchers through means of research. In contrast to categories of practice, it is largely detached from daily experiences[14] and offers at least some degree of legitimacy to their claims, aiming to "situate events within a meaningful framework, to identify patterns, structures and logic". [13]

Categories of Practice

[edit | edit source]In categories of practice, it is believed that humans are sexually dichotomous - male and female. Biological sex is virtually synonymous and interchangeable with gender, and along with it comes assumptions about the exhibition of feminine or masculine behaviour and sexual attraction to the opposite sex. This binary paradigm is widely recognised as the truth by many individuals and societies. In sociology, categories of practice is often associated with essentialist ontological perspectives, which forms its truths around the belief that the differences between the two genders are natural and inherent; the separation between males and females in a social context is - in at least some measure - a direct product of disparity in biological makeup, hence it is universal and consistent over time.

Categories of Analysis

[edit | edit source]On the other hand, categories of analysis disagrees with this understanding of sex, gender and their relationship. Though there still is debate surrounding the number of sexes in the academic world, most propose at least 3 sexes, commonly including intersex as a third category to male and female.[15] However, many specialists also explore beyond these three categories to add to the sexes, particularly by attempting to categorise the plethora of variations under the intersex umbrella. Nonetheless, the truth to most contemporary biologists - particularly geneticists - is that a binary structure is an oversimplification of reality, and it has been proposed that a spectrum of sexes would be more accurate, making up for the multitude of variations in sex that are unaccounted for by the binary categorisation. [16] With the lack of limiting constraints in sex in academia, gender is also often considered multiple in the terms that gender is defined as the classification of male and female behaviour, and the truth is that there are a multitude of ways to express oneself as male or female on a spectrum of masculinity and femininity. There is also a distinctive lack of connection drawn between sex, gender and sexual attraction. In sociological studies, categories of analysis are often linked to social constructionist theories. The constructionist ontological position argues that the concept of gender is purely a product of social and cultural construction. The binary gender system and the ascribing of certain appearances and behaviours to femininity and masculinity is non-universal and gender norms are variant across different cultures and changing with times.

Essentialist and Constructionist Ontologies of Sex and Gender

[edit | edit source]Thomas Laqueur, a historian, sexologist and writer, asserts in his book ‘Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud’ that prior to the eighteenth century, a one-sex model existed in Europe. This model stated that men and women symbolise two distinct forms of one sex, that is different genders existed, but only one sex. This meant that both genders possessed the same genital structure with the only difference being that the female genitalia was located inside the body, as the vagina was interpreted as an inverted penis. Laqueur argues that ample medical and philosophical literature supported the view. For example, during Galen’s time, a physician, surgeon and philosopher belonging to the Roman empire, there were few words that differentiated between male and female anatomy.[17] From the constructionist view of reality, the absence of words describing female genitalia meant that no differences were identified at the time. By extension, constructionists assert that one’s physical morphology is only significant through socially-imposed meanings.[18] After scientific advancement, abundant literature was found that explained the two-sex model which fuels the truth we subscribe to today. This contends the essentialist view that ‘male’ and ‘female’ categories are ‘natural,’ as it was not until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that the essentialist meaning of biological sex became what it is today; that is that two, separate and opposite, sexes exist. Jacques-Louis Moreau, a surgeon and physicist, elaborated that "not only are the sexes different, but they are different in every conceivable aspect of body and soul, in every physical and moral aspect. To the physician or the naturalist, the relation of woman to man is a series of opposites and contrasts". [17] Biological differences soon became the basis for contesting women’s and men’s social positions. From the ‘constructor of reality’ view, essentialist contentions of gender are effects of dominance that aid a hegemonic and legitimating function.[19] For example, in cases of ambiguity in the dichotomous gender membership – be it physiologically or behaviourally – essentialists legitimise greater enforcement of categorical boundaries through “social and economic sanctions for ‘deviance’ from ‘male’ and ‘female’ role expectations,” and “surgery to correct ‘deviations’ from ‘objective’ biological categories.” Hence, essentialism’s binary categorisations of sex and gender are a method of naturalising male privilege over women and valuing an individual’s physiological appearance over their personal identity and relationships.[20]

Consequently, social constructionism is criticised for ignoring the existence of ‘reality,’ as many arguments present dichotomous oppositions of ‘reality or social construction.’ [21] Such arguments imply that a discipline/approach “deeper and ultimately more stable” than social constructionism (such as biology) can only be called ‘real’.[22] However, reality as a concept is highly contested, politically and in academia, in that it is hard to justify the ‘reality’ of the relationship between gender and sex. All the definitions of ‘real’ are not considered socially equal and the ability to define such relationships itself depends on one’s position in the power structure.[23] Having said this, current arrangements of sex and gender are ‘real’ in the sense explained by the Thomas theorem, that if people collectively “define situations as real, they are real in consequences”.[24] That is, social divisions of gender and sexuality affect those that live within them and shape their lives to a large extent.[25]

An evolutionary explanation that provides an understanding of gender identity from a phenomenological approach that reflects the social perception of evolution is that as a consequence of social gender roles in society in the past (the 19th and 20th century) such as having households with a male breadwinner and a female homemaker, each sex experienced different circumstances, such as the male had to hunt for food while the female had to take care of children, prepare food and do the housework.[26] The different exposure to experiences increased the adoption of different behaviours between the two sexes.[27] People experience different situations and interpret different ways to react and behave as a consequence. As society has evolved, male and female individuals equally experience having a job to earn money and housework. As the standard gender roles have evolved, the different sexes are exposed to varying situations which require the need to adopt different behaviours in order to adapt to the change. This includes male individuals being exposed to tending to a child and housework which require sensitivity and passivity that are stereotypically female-associated behaviours and female individuals being exposed to harsh work environments which require aggressiveness or competitiveness that are stereotypically male-associated behaviours.[28] This is a result of being provided the information of the process of different tasks to interpret how to react and behave in these newly exposed fields. However, as the choice in certain subjects and choice job roles continue to follow a divided field of jobs between male and female individuals, in the majority of the population, gender differences in behaviour persist.[29] On an individual level however, both sexes have an equal opportunity to be exposed to different work that is not gender-typical, hence allowing the adaptation of opposing gender-typical behaviour individually. Over time, as individuals continue to reduce the sex gap between different fields of work collectively, exposure will increase, consequently leading to the adoption of different behaviours that can explain an individual’s choice and satisfaction of their gender identity.

Alternative Approaches towards Analysis

[edit | edit source]Through a positivist approach to the truth in gender, researchers have studied how the truth of an individual’s gender identity as a result of sex-determining hormones which are chemical messengers that travel through the blood. Researchers identify that the reality of hormonal effects within the body produce knowledge of one’s gender identity. Testosterone is a hormone which is commonly produced by the male testicles, and is hence identified as a male sex-determining hormone. (Females also produce testosterone but in relatively smaller quantities).[30] Testosterone is released in the womb during a prenatal period and this hormone can affect the brain and influence appearance, sexual development, and develop stereotypical male-associated traits such as aggressiveness, competitiveness and enhances visuospatial abilities which has been understood through an evolutionary explanation that men majorly required such abilities to hunt for food.[27] In 2004, Hines, Brook and Conway conducted a cross-cultural study with participants that have a genetic disorder called congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) where they experience increased levels of androgen during the prenatal period. Androgen are male-sex hormones such as testosterone. Normally, after birth, the hormonal imbalance is noticed and the child undergoes corrective hormonal therapy, however, it was found that the hormonal increase during the prenatal period can have irreversible effects. The study was a comparison between groups of participants with and without CAH. They found that female born participants affected with CAH had a childhood history of significantly associating with male-typical play behaviour such as playing with stereotypical male toys, spending time with other male children, and participating in rough play. Additionally, they experiences a decrease in interest of heterosexuality and a decrease in satisfaction of their female sex assignment during adulthood. These were significant differences in comparison to female born participants that were not affected with CAH.[31] However, it was also identified that the participants did not completely form a transition to male-associated behaviour, and that they were more likely to demonstrate male-typical behaviour, rather than completely. This signifies that there are other influential factors such as cognitive, cultural and environmental determinants.[27]

In 1967, a psychologist called John Money came across a case of twins that had to undergo circumcision at the age of 7 months due to a medical condition. The twins were Bruce and Brian, however, during the procedure, Bruce’s penis was burnt off due to complications in the surgery. Money aimed to test his hypothesis that gender identity is influenced by they social environment in which one is brought up in and he suggested that Bruce should be raised as a girl and made him undergo sex reassignment surgery by constructing a functional vagina and was brought up with the name Brenda. Money was then able to compare the two twins being brought up differently socially, Bruce as a female gender and Brian as a male gender. Brenda was also forced to dress like a girl and induced with female sex hormones such as estrogen to develop the growth of breasts. In 1997, Bruce explained that the experience was traumatic and that even though he was raised as a girl, he did not develop a female gender identity. This disparity in the way he was raised and his internal conflict of gender identity caused him to become depressed and he developed suicidal thoughts, which were enforced through bullying by peers. Bruce eventually underwent a sex reassignment surgery and testosterone treatment to reverse the effects. He changed his name to David. In 2004, David (Bruce) committed suicide after his wife left him. Ultimately, the forced adopting of a different gender through different behaviour choices and different experiences from a change in social upbringing, in the context of this case study, exhibits that gender identity cannot be socially constructed, and can instead manifest identity crises and traumatic experiences.[27] Bruce experienced gender dysphoria as he was forcefully made to adopt a female sex at a young age through sex reassignment, yet he was unable to adopt the gender identity typically associated with the sex.[32] This counters that gender is a social construct. An individual’s true gender identity is not constructed by their social upbringing and expectations placed on them by the family or peers. It is instead an interpretation of oneself which highlights a phenomenological approach to the truth of gender identity. The truth in the context of gender identity is the result of the internal individual perception of oneself about which gender identity they are most satisfied with.

The Divergent Truths of Gender in Different Cultures

[edit | edit source]In line with the constructivist view of gender, research or the concept of gender in a multitude of societies supports that the dichotomous gender structure of male and female is not universal across different cultures and societies.[33] Some examples will be explored below.

Note: Definitions of genders are constructed differently in every society; it is impossible to directly translate the meanings of certain genders into English, especially terms that stray from the English language's limitation to expressions in terms of a binary gender structure.

Non-binary gender systems are prevalent in many Native American tribes. One example is the Native American Navajo tribe. The culture and language of the Navajo tribe traditionally, recognises four genders: Asdzaan, Hastiin, Nadleehi and Dilbaa. In rough translation, Asdzaan is a feminine female; Hastiin is a masculine male; Nadleehi translates to "one who constantly transforms" and are used to refer to intersex and male-born individuals who function with the role of a female; Dilbaa are used to refer to female-born individuals who function with the role of a male. However, colonialism has greatly affected the Navajo people's understanding of their terms for gender, with Dilbaa phasing out and Nadhleehi becoming an umbrella term for both the third and fourth genders. Some also consider there to be five genders by separating Nadhleehi into three subcategories: male-bodied Nadhleehi, female-bodied Nadhleehi and intersexed-bodied Nadhleehi. However, modern day Native American society still holds a lot of prejudice towards intersex people who did not fall into the Eurocentric gender model of male and female as a result of European colonisers forcing their binary gender system into Native American tribes by mass executions of those who did not conform to either group. Many tribes have since internalised these values and intersex Nadhleehi have been driven to live in shame and secrecy of their gender and sex. [34]

Production of Truth in Gender

[edit | edit source]Sociologists view gender as taught and learnt behaviour, hence, there is a methodology by which the truth of gender is produced. This is called socialisation. Socialisation is a fundamental concept in sociology which refers to the life-long process where humans learn the cultural norms of the society they are a part of in order to behave as a member of the group. This learning is then internalised, thereby forming social identity in the process. Applying this concept in the context of gender, gender socialisation is the process of interaction and experiences where individuals learn gender norms and develop a gender identity. To define these terms as they are used in sociology: Gender norms refers to what's considered appropriate feminine and masculine behaviour in society. Gender norms make up gender roles (sometimes referred to as sex roles), which are the patterns of behaviours that individuals are expected to exhibit based on the gender they have been ascribed by society. Internalisation is when these expectations from society are absorbed and accepted to become part of one's own values and identity.[35] Internalisation of gender norms and roles forms our gender identity, which is the way in which we view and define ourselves in relation to our assigned gender and sex. [12][36]

There are a multiplicity of theories on how socialisation takes place and the roles of agents of socialisation, however, all sociologists will agree that socialisation occurs through interactions with the society around us. Agents of socialisation are everywhere, as explored in the following:

- Assigning of sex at birth - Socialisation begins at birth when the child is assigned a sex (and hence the according gender as per understanding of sex and gender in categories of practice). They will then be classified as such and treated with regards to this classification. [36] This is particularly significant for parents, as they are the primary caregivers who have a large influence on the gender socialisation in the early stages of a child's life.

- Sex-typed behaviours - Sex-typed behaviours refer to behaviours which are often seen to be more appropriate or less appropriate for different genders. Socialisation occurs when children are rewarded or punished for exhibiting these behaviours deemed appropriate or inappropriate for their assigned gender. An example would be crying; girls are more often comforted when they cry, while boys are more likely to be corrected for their behaviour. [36] The child learns and internalises what behaviours are acceptable and expected of them. This is a process of the social learning theory developed in 1977 by Albert Bandura that individuals learn behaviours by observation and one of the meditational processes in the theory is motivation. A behaviour is continued or discontinued through a difference in motivation such as being rewarded or punished for the behaviour.[37]

- Realisation of gender constancy - According to cognitive-development theory, children develop understanding of gender constancy (association of gender with permanence) at 7 years old. This understanding motivates them to learn to act in line with their gender by identifying and selecting behaviours consistent with their learned gender identity.[36]

- Sex-typed play - Children's play is also often sex-typed. Children at a stage of gender constancy would observe and learn to associate certain toys to certain genders from their peers or the media (such as television shows, commercials, cartoons etc.) and consequently show more interest in engaging with toys that are connected to their gender while expressing avoidance towards play that is associated with the opposite sex. This outlines the process of the social learning theory by Bandura as it supports that individuals learn and adopt behaviours by observation and imitating others.[38] This is supported by an experiment carried out where children were shown a commercial of the same gender-neutral toy with either two boys or two girls playing with it. According to the results "children who saw opposite-sex children playing with the toy avoided spending time with the toy and stated verbally that the toy was more appropriate for an opposite-sex sibling". [39]

- School subjects - In educational institutions, a gender related classification of subjects is often present. Gender stereotypes tend to cause separation of subjects into those females are encouraged or allowed to study and those they “don’t need” and are not expected to do well in. In gender-segregated schools some subjects are not taught at all while in co-educational schools girls can be underrepresented in certain classes due to rules, pressure from family, teachers and costudents. Boys are encouraged to and expected to be interested in specific subjects as well. This can be internalised, shaping the ideas and interests of the individual to develop a preference towards the subjects they are expected to study or excel at. [40]

- Religion - Many religions often teach traditional gender roles by depicting the image of women being subservient to men. Individuals who grow up in religious environments are suscept to understanding and internalising these values. This is supported by a study into the frequency of praying and the acceptance of traditional gender roles carried out in America, where there was a significantly higher percentage of people who accept traditional gender roles in the group who pray daily as compared to groups who pray weekly or rarely.[41]

Truth of Absract Concepts

[edit | edit source]Truth in Beauty

[edit | edit source]According to Cambridge Dictionary, beauty is defined as “the quality of being pleasing, especially to look at, or someone or something that gives great pleasure, especially when you look at it”.[42] However, in reality, such an abstract concept has no universal definition: it is a word whose meaning varies on an individual-to-individual basis because of its phenomenological and subjective nature. As a result of this, the truth in beauty will also vary from person to person — this arguably suggests that the truth in beauty is perhaps non-existent; and that the very hypothetical existence of it is only socially constructed. So with beauty being an aesthetic experience which is reliant on individual preferences, taking a positivist approach in pursuing the truth of it is unsurprisingly very difficult.[43] This phenomenon is counterintuitive in nature because of the general consensus that indicates there is always conflict between subjectivity (being the concept of beauty) and objectivity (being the neurological study). However, in the emerging field of Neuroesthetics, scientists have found ways in applying the scientific method, in which the epistemological essence of the method is inherently related to the correspondence theory of truth, in an attempt to reach closer to the truth of beauty.

A Positivist Approach in Neuroaesthetics

[edit | edit source]Semir Zekir, a University College London professor and a renowned pioneer of Neuroesthetics, advocated that: “It is only by understanding the neural laws that dictate human activity in all spheres — in law, morality, religion and even economics and politics, no less than in art — that we can ever hope to achieve a more proper understanding of the nature of man.”[44]

In his studies such as the Brain-Based Theory of Beauty, he inquired the origin of the beauty experience in the brain. He empirically investigates this by using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) that measures the blood flow in the brain. The level of blood flow in a certain part of the brain corresponds to the level of brain activity in that specific region of the brain. In his aforementioned research, he successfully found that the medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC), the brain’s ‘pleasure’ centre, is stimulated when an individual encounters a stimulus (both visual and aural) that is ‘beautiful’ and ‘ugly’ to them.[45] The level of blood flow in the mOFC correlates with the stimulus rating given by the participants: the more ‘beautiful’ something is, the greater the blood flow in the mOFC.[45] Several other studies investigating the experience of beauty reflect the same or very similar results.[46] In these studies, it is demonstrated that approaching such a subjective concept from a positivist standpoint is feasible and the results are valuable in the pursuit of the truth in beauty. Furthermore, it shows that a relationship between objectivity and subjectivity can be established without friction (or even show that beauty can be intersubjective).[47]

However, this raises the question: Is such a method epistemologically sound and foolproof in its entirety (in arriving closer to the truth in beauty)? In some studies, it is shown that brain stimulation from visual and aural aesthetics is not always found in mOFC exactly.[48][49] This highlights the concerns critics have of Neuroesthetics and its goal of objectively achieving the truth in a subjective concept (such as beauty). Researchers Conway and Rehding counter argued studies like Zekir’s Brain-Based Theory of Beauty noting that: if one were to experience beauty without activation in the mOFC, should their experience be rejected, or even considered anomalous?[50] They expressed their concern about how, if such a positivist method is taken to determine the truth in beauty, there will be a potential loss of that truth inadvertently. This is due to the restrictive nature of science and its grounded roots in the correspondence theory of truth (as mentioned previously). The correspondence theory of truth heavily relies on facts, and with the general scientific method (of which falsification is embedded in) and its reductionist core, there will always be a limitation to reaching that truth holistically. Investigating through a positivist lens does not encapsulate the entire truth in beauty. This may be because of how we all experience beauty differently, and what is beautiful to us may not be beautiful to the next person. In this case, we all may be making our own version of reality of what is beautiful, which means that there are actually multiple realities that would be existing. This would conflict with the correspondence theory of truth that is arguably at the heart of science: where only one reality exists and where only one truth exists.[51] Having said that, the truth in this instance may simply be an aggregation of multiple truths. However attaining data on a grand scale like that and reducing it to an average would, as mentioned, minimise and leave out experiences out of the mean range, referring to those data points (or experiences) as anomalous — even though each experience and data point holds its own meaning and its own value and should not be denied only because of the empirical and objective nature of science.

Constructivist and Phenomenological Approaches in Sociology

[edit | edit source]‘Beauty’ is considered an aesthetic experience that is individualistic to one’s preferences and their own definition of ‘beauty’.[43] As a possible result of this, one can say that there may be a multiplicity of different truths in beauty that exist on their own individually and simultaneously. Alternatively, researchers (not only limited to those specialising in sociology) have also argued that, instead of that, the truth in beauty does not actually exist: this may be attributed to the fact that it is a concept so abstract, so multidimensional and so experientially-dependent that the real meaning of and truth in beauty simply cannot exist.[52][53]

However, instead of those two aforementioned extremities of truth in beauty (where it either exists or does not), what is definitely most prevalent in many cultures is that beauty is socially constructed — regardless of whether true beauty exists or not. Beauty standards are culture-specific sets of ideal physical qualities that are most attractive to the human eye which greatly varies over time.[54] Although they are not necessarily the truth, they are so conspicuously and undoubtedly embedded within society that these outlined beauty standards therefore are purported to be as such. These beauty standards form an illusion of truth, in the guise of ‘true’ truth, resulting in them being the generally-accepted and societally-agreed truth. (It is arguable as to how close to or far from the real truth in beauty they truly are.) Therefore, through a sociological lens, the truth in beauty is formally considered to be constructivist in nature.

For such an exclusive group of ‘ideal’ aesthetic qualities to be so deeply rooted in society signifies that it is through immensely powerful tools that that can take place. Consumer capitalism, social media and anti-feminism have been accused of propelling this notion of truth in beauty within society. Majority of them are enabled by large corporations within the beauty industry. Consumer capitalism exploits the society by capitalising on insecurities which, much like beauty standards, have been manufactured on what seems to be baseless grounds — as one cannot truly identify the truth in those institutionalised insecurities.[55] Due to the coercive nature of consumer capitalism, “beauty propaganda” has shaped our psyche into believing their fiction and their belief of true beauty, and has grown to become a global phenomenon that bears great influence unto other cultures and their conceptions on what true beauty is.[56][57][58] With the help of great technological advance and social media, the quick widespread of advertisements is enabled further and beauty propaganda is artificially strengthened and made more visible in our everyday lives.[58] Our constant consumption of social media embeds the marketised notion of true beauty into us and on a larger scale the society. This therefore makes it difficult for one to simply reject or even challenge that social norm that that form of beauty is true beauty.

Beauty in the Digital Age

[edit | edit source]In today’s increasingly digital world, our perceptions of beauty have become synonymous with their portrayals on social media. The practice of altering photos has existed for almost as long as photographs themselves, but with the creation of digital editing softwares such as Paintbox and Photoshop in the late 1980s and early 90s, the frequency and quality of manipulated images skyrocketed.[59] Shortly after, the fashion industry began digitally manipulating images of models to make them look closer to the industry’s standards of beauty.[60] Before long people began to question the ethics of digital image manipulation.[61] Despite these early concerns, “airbrushing” - the digital alteration of images, became commonplace in the world of fashion and advertising.

The late 2000s saw the emergence of growing calls for transparency regarding airbrushed images in the fashion and advertising industries.[62][63] Many of these demands came from well-known celebrities who had experienced airbrushing first hand, such as Kate Winslet,[64] Lady Gaga,[65] and Zendaya.[66] In response, some companies have either stopped or reduced their use of photoshop or made the instances of it’s use more apparent, including Dove and Seventeen magazine.[67]

Owing to the time and money required, image-editing technology was once only commonplace in magazines and advertising. However, since the creation of image-based social media apps like Instagram and Snapchat the ability to add filters to, or retouch, images has become available to all those with access to a smartphone. Consequently, we now live in an era of such widely accepted alteration of appearance, that the choice not to alter an image is often publicised as a point of pride, as in the #nofilter Instagram trend which has resulted in the use of said hashtag over 250 million times.[68] This would suggest a continuing demand for authenticity in the portrayal of images on social media and yet, research by the University of Windsor found that in a sample of 18,000 images that used the hashtag, 12% of these photos had actually been filtered.[69]

Truth of True (Interpersonal) Love

[edit | edit source]Love is a universal feeling of intense affection experienced by individuals.[70] Love itself is measured through its presence or absence instead of quantifying it. Many people proclaim their love for someone, yet this does not guarantee that the love will last forever. People experience separation through break-ups and divorces which are official endings of an intimate relationship.[71] While individuals feel love, whether it is true or not, whether they are actually feeling true romantic love or not, has been studied through three epistemological approaches.

A Positivist Approach

[edit | edit source]Through a positivist approach, it has been studied individuals in romantic love experience a neurobiological process. Dr Helen Fisher conducted a research study using a functional Magnetic Resonance and identified that when an individual is engaged in thinking about a person they are romantically in love with, the mesolimbic dopamine pathway activates which consists of the ventral tegmental area and the caudate nucleus. This is in contrast to no activation of the pathway when the individual is engaged in thinking about a neutral acquaintance.[72] Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that is a chemical messenger of pleasure and reward in the nervous system.[73] This research indicates that when a person thinks about the person that they are in love with, their brain receives a pleasure response through the dopamine and feels rewarded. The feelings mirror real biochemical reactions within the body to produce knowledge that the love is true.

Another form of truth of romantic love through a positivist approach is how an individual’s major histocompatibility complex (MHC) influences their selection of a partner. The MHC is a complex network of an individual’s body odour, genes and immune system. The complex operates in a way that partners with high variation and differences in MHC genes will produce off-springs with a stronger immune system as it will become ‘more broadly defensive’ with the variety in the inherited immune function. An evolutionary approach explains that humans have evolved to be able to detect whether they are MHC similar or dissimilar with another. Research by Penn in 2002 has indicated that individuals prefer the scent of MHC dissimilar genes.[74] A study by Wedekind in 1995 consisted of female participants rating ‘sweaty’ shirts by attractiveness which were worn by the male participants. The research indicated that the female participants’ attraction to a shirt being more pleasant was towards the shirts belonging to MHC dissimilar male participants. Furthermore, female participants were twice as likely to be reminded of their romantic partner when smelling the shirts of MHC dissimilar male participants.[75] The human biological function using the olfactory bulb to recognize scents of MHC dissimilar individuals and their attraction towards them mirrors the reality of evolutionary needs. Individuals feel love for the relationship itself, due to the consequences of high evolutionary gene conservation through inheritance to off-springs.[76]

A Phenomenological Approach

[edit | edit source]Through a phenomenological approach, humans have cognitive determinants that determine whether they further develop their relationship, and hence develop feelings of love. These cognitive determinants are their perceptions on the relationship, and whether they interpret the relationship as one that they can feel love. One cognitive determinant is reciprocity which is the experience of a social exchange in a relationship. This exchange enforces feelings of attachment towards people that feel the same about the individual. This supports an individual’s ‘self-esteem, self-enhancement and self-verification’ where the individual and their behaviour and choices to develop and present themselves are being validated by the people who like them. In 1959, Dittes conducted a research study and found that individuals that were accepted in a group affectionately felt more attracted to the group, in contrast to being poorly accepted in a group, in which they felt less attraction to the group.[77][78] Additionally, in 1982, Kenny and La Voie found that over time, reciprocity increases, causing an increase in attraction between individuals, and consequently developing mutual feelings of likeability. This could also advance towards feelings of love.[79] Reciprocation is perceived by an individual. They perceive whether they feel liked, welcomed or accepted, and interpret this information and experience to develop feelings of love.

Another cognitive determinant is familiarity. Familiarity is a concept that is based on the mere-exposure effect which was studied in 1968 by Zajonc and Mcguire, wherein the increase in exposure of a person or an object increases an individual’s liking towards it.[80] This indicates that repetitively being in a person’s presence increases the liking towards that person by enhancing one’s attitude towards them. Another theory is the attraction-similarity model which highlights that individuals are attracted to people that they perceive to be similar to themselves. This similarity could include, but is not limited to, age, culture, ethnicity, religious beliefs and socioeconomic status.[81] This model is a basis of perception of similarity, and not similarity itself. Perceived similarity increases when an individual becomes more attracted to another person. In 2005, Morry found that as their attraction increases, they perceive more similarities, even if there are not actual similarities, and this results in an increase in satisfaction in the relationship, where the individual consequently feels more liking towards the relationship and the individual in the relationship, and develop feelings of love.[82]

Furthermore, a perception based approach is the matching hypothesis which posits that individuals develop a perception of themselves in terms of their own attractiveness and social desirability, and become attracted to partners that they perceive to ‘match’ their levels.[83] In 1971, Berscheid identified that the matching hypothesis indicates a stronger prediction of approaching an individual based on perceived matching level of social desirability, than the actual feelings of likeability and desire to pursue the individual romantically.[84] In 2011, Taylor found that in a real life application, participants who held high or low perceptions of self-worth and social desirability, were both more likely to be attracted to people they perceived to have a high social-desirability. However, it was also found that the matching was based on different degrees as there were many variables that could match.[85] However, as a person is more approachable, there is an increase in opportunity of interactions which leads to the familiarity process and the mere-exposure effect. This bases attraction on an individual’s perception of social desirability of another person, regardless of the perspective of their own. Individuals perceive social desirability and either in terms of approachability or attractiveness, increase their encounters, and develop satisfaction. This consequently allows the individual to develop feelings of likeability, which can further evolve into feelings of love.

A Constructivist Approach

[edit | edit source]Through a constructivist approach, the social origin of interpersonal love is examined as relationships themselves are social interactions between social beings. Ultimately between two different types of cultures and societies, there are differences. There are differences in the choice of marriage, verbal expressions of love, and choice of partner between individualistic cultures and collectivistic cultures. The former values the priorities of the individual while the latter values the priorities of the group collectively. In 1993, Dion and Dion found that in individualistic cultures, individuals are more likely to choose marriage on a basis of romantic love, whereas in collectivistic cultures, many individuals choose arranged marriages which values the importance of the family’s perspective.[86] (Due to acculturation, where different traits of cultures are adopted, there have been changes in this choice as humans and cultures have evolved socially).[87] This contrast does not mean that couples in arranged marriages do not love each other. In 2012, Regan, Lakhanpal and Anguiano found no significant difference in satisfaction, commitment, happiness and love ratings between individuals in love and arranged marriages.[88] This may have however been influenced by the obligation by individuals from collectivistic cultures to maintain social harmony and refrain from sharing negative thoughts of their marriage as it was a decision made collectively with a family/community being involved in the decision-making.[89] Additionally, in 2012, Karandashev highlighted a study by Nadal in 2012 that in collectivistic cultures, individuals refrain from expressing love verbally on a daily basis and are instead only verbally expressed on special days. Individuals in collectivistic cultures instead express love through actions, such as sharing time together, helping each other out, or working together on an issue that they find important. In individualistic cultures, individuals are more likely to express their love verbally to each other.[90] The cultural differences in the two types of societies express different representations of love. However, the form of expression of love does not have one way for it to be true. The expression of love is culture dependent, and whether it is expressed verbally or indirectly, or it starts before or after marriage, the existence of love is true as social beings experience different feelings and are able to discern with their knowledge that what they are experiencing is love.

In 1973, Altman and Taylor developed the social penetration theory which explains that as individuals shift what they share from a shallow level to an intimate level, and through reciprocity of this intimacy, their relationship develops further.[91] Sharing on an intimate level includes, but is not limited to, discussing feelings, emotions, perspectives, doubt on self-identity and self-confidence. In 1994, Collins, Miller and Steinberg further found that individuals that share/disclose intimately are more likely to be liked than individuals that share shallow discussion and the individuals themselves tend to like the people that they have shared with, through a sense of comfort. Additionally, individuals naturally choose to share more intimately with others that they initially liked.[92] Furthermore, in 1992, Dindia, Allen and Steinberg found that there are significant sex differences in the quantity of self-disclosure and sharing where women significantly shared/self-disclosed more information/feelings (and more to other women, especially when they share to a ‘friend, relative or spouse’) than men.[93] Self-disclosure is a means towards becoming intimate with someone, while after an individual is already intimate, self-disclosure is a form of representation that indirectly expresses the existence of likeability towards the person as it enforces and ensures that they continue to trust the person. The sex difference does not mean that love by one sex is true while the other is false. There are different ways of self-disclosure, and women significantly express this verbally. In 1978, Davis found that men significantly self-disclose more than women in situations such as initial encounters.[94] This inconsistency presents the different representation of self-disclosure as women significantly self-disclose throughout the relationship, while men significantly self-disclose during the initial period of the relationship. While the circumstances are different, self-disclosure is a common representation of the existence of trust in each other and existence of liking towards each other as per the social penetration theory.

Another constructivist approach towards understanding the existence of true love is the attribution theory which identifies that individuals ‘attribute’ behaviours to their causes to better understand their own behaviour, as well as the people around. Attribution is generalized into two categories; situational and dispositional. The former is when an individual attributes a person’s behaviour as a result of the situation, while the latter is then an individual attributes a person’s behaviour as a result of their personality (their disposition to behave in such a way).[95] In 1983, Fincham and O’Leary conducted a study between ‘distressed and non-distressed’ couples and found that individuals in a distressed relationship significantly attributed positive acts of behaviour by the partner to a situational cause and attributed negative acts of behaviour to a dispositional cause. Furthermore, it was found that individuals in a non-distressed relationship significantly attributed positive acts of behaviour to a dispositional cause and attributed negative acts of behaviour to a situational cause. This means that happy couples believed that if their partner behaved positively, then it was global, controllable and part of their personality, while if they behaved negatively, then it was due to an uncontrollable situation. In contrast, couples that were distressed believed that if their partner behaved positively, then it was uncontrollable and due to their surrounding situation which forced them to act positively, while if they behaved negatively, then it was a global, controllable action and it is part of their personality to naturally conduct negative acts of behaviour.[96] Additionally, in 2000, Karney and Bradbury conducted a longitudinal study and found that attribution style and relationship satisfaction is dynamic and ultimately, a causal relationship was identified between the two where attribution style is more dominant. It was found that a change in attribution style is predictive of a change in relationship satisfaction. Universal expressions, especially negative universal expressions which claim that a partner ‘always’ or ‘never’ does something/acts in a certain way significantly influences the perspective of the partner and the relationship.[97] The attribution theory in the context of love indicates that the choice of attribution by individuals in a relationship towards their partner significantly affects the perception of the partner, and the feelings towards them. A change in attribution towards a negative style ultimately changes the feelings of love. It was demonstrated that satisfied couples believed that positive acts were dispositional, indicating that their perception of the partner is positive and enforces the existing feelings of love. The different representation in choice of attribution of a partner through verbal expressions developed from an individual’s perspectives ultimately identifies the existence or non existence of the feeling of love by consequently enforcing the feelings of love or not. This process of attribution shares the knowledge of whether the individual feels love for the partner or not through attributional expressions, and influences the dynamics of the relationship in the near future.

Truth of Life and Death

[edit | edit source]Death is the end of life, while life is existence in the world.

A Positivist Approach

[edit | edit source]A positivist approach would identify life through the features of life’s process which has an acronym: MRS GREN. This presents that life consists of undergoing movement, respiration, sensitivity, growth, reproduction, excretion, and nutrition. This means that all living life is able to conduct and experience the features of the acronym, MRS GREN.[98] Death is consequently the end of life, and through a realist scientific approach, death is the end/’cessation’ of the ability of a living being of conducting the biological functions of MRS GREN. Death is represented as the end of the biological functions that work to sustain life.[99] This suggests that the truth of life and death through a positivist approach is merely based on empirical evidence, thus when none of the features in MRS GREN are experienced, one ultimately encounters death.

A Phenomenological Approach

[edit | edit source]Through a phenomenological approach, life is identified as the ability of being aware of one’s surroundings and being able to decide their actions. In John Keats’ Ode on Indolence, the author is aware of the presence of ‘love’, ‘ambition’ and ‘poesy’, yet he is able to perceive that they are incapable of drawing him away from the comfort of a lazy day. He is aware and perceives the three ‘figures’ as inferior to indolence. The author decides for himself to choose numbness from his interpretation of the worth of his laziness and his interpretation of what is valuable to him; his indolence.[100] As death is the end of life, phenomenologically, death is visioned from the human imagination of what it is. In John Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale, the author contemplates escapism of reality through death. He is able to imagine that death is ‘embalmed darkness’ and is like ‘sleep’. The author escapes to another realm of beauty and immortality in his mind as he listens to the song of the nightingale, yet he comes to question whether he actually escaped, or remained in the mortal realm the entire time and was only dreaming of immortality. The awareness of what is real, presents that the author was in life, but as he escapes into another imagined realm of immortality as the song of the nightingale never ends, and as he loses sense of what surrounds him, he experiences death. He contemplates whether he should stay awake in the real realm, or remain in an eternal sleep that is death.[101] Therefore, a phenomenological perception of the truth in life and death is completely dependent on the individual's experience and interpretation of what is around.

A Constructivist Approach

[edit | edit source]A constructivist approach identifies life as the ability of experiencing feelings and the knowledge that one is able to influence feelings. In John Keats’ Ode to Psyche, creative imagination is used to develop a construction of an ideal form of love for the author. This imagination allows the author to be aware of what he can do in his imagination, such as building a ‘shrine’ for Psyche, and being her ‘priest’, in his imagination. The author’s imagination is never-ending and infinite, and can completely feel love passionately at the present moment. This vision brings forward that being human, and being alive is the result of the cultivation of one’s unconscious and attempting to represent experiences in real life in one’s own way of how they felt from the experience.[102] Life, and being alive through a constructivist approach demonstrates feeling emotions and experiencing feelings at the present moment, and being able to take away an understanding of oneself through those feelings. The poem presents how the beauty of love can become immortalized through imagination.[103] As death is the end of life, constructively, death is when one is no longer able to experience feelings, or influence others to feel. In Ode to a Nightingale, Keats refers to the song bird as ‘immortal’. He indicates that since the ‘ancient days’ people have heard the song of the nightingale, and till the present day, people are still able to hear the song. The bird itself continues to share its beautiful song and continues to influence people’s feelings of happiness and allows people to develop a sense of euphoria. It is here that the bird becomes immortal and transcendences beyond life. This poem presents symbolism of the nightingale and humanizes the bird.[104] The author can similarly attain immortality, even if not physically, through his knowledge represented as poems, as they continue to influence feelings from readers. Through a constructivist approach, the representation of death and the construction of the concept of death allows the ideology that one can escape death and remain immortal if they can continue to affect people even after they physically cease to exist.[105] This signifies that a person truly experiences death when peoples’ feelings are no longer evoked by the person and when there is no one that remembers the person anymore.

Truth in Art

[edit | edit source]Truth in Historic Paintings

[edit | edit source]There are many claims of truth concerning historic paintings, in History and in Visual art, ranging from the questions of authenticity of artworks to the true intentions of the artists, historic contexts of artworks, and the true meaning and significance of art. Some truths in art seem to be more certain than others because they can be proved or disproved in accordance with positivist approach. For example the age of various paintings can be proved through scientific investigations, or authenticity of paintings can be understood. A spectrometer showed that a painting that was believed to be created by Chagall was fake. Phthalocyanine blue, which became available as a watercolor only in the 1930s [106] was used in this supposedly 1909-10 painting. [107] It is easier to disprove a truth claim than to prove it, as little as one inconsistency can be accepted as sufficient evidence. In order to fully prove a claim, a complete awareness of all the contributing factors is necessary, which is rarely possible in art and complicates the search for truth.

Truth in Old Portraits

[edit | edit source]Artworks are frequently used to learn about history and past events and the extent to which that is possible is debatable. Our understanding of appearances of historic figures tends to be based on paintings. When paintings are used for that purpose it is much harder to prove or disprove the claims of truth as many more factors are involved and their analysis rarely results in complete information. There are some factors that suggest that portraits don’t necessarily represent the “objective reality”. The extent to which the paintings represent and are able to represent the truth is debated.[108]

Some researchers are ready to see portraits as historic documents that describe specific true details of the past or general truths about historic periods. Portraits were normally expected to represent the appearance of the model as closely as possible, so it is reasonable to suggest that they may represent the truth about appearances of specific people of the past. Portraits are sometimes seen as “visual primary sources” of information about the past, as they were made from life and put the viewer in place of the artist, a contemporary of the subject.

[109]

However, the portraits were created by people, hence they are subjective. Artists are subjective witnesses and arguably can’t reflect the truth because they can’t apprehend the complete truth in the first instance.

[109]

An artwork would still contain some truth about the past even if that was not the intention of an artist, as the artist was influenced by contemporary society and beliefs, and unconsciously accepted certain things as the only possible reality and conveyed it through own artworks. While that may be true of some historic details, facial features in a portrait would be insignificantly affected by this.

Paintings are extreme simplifications of reality and that distances them even further from depicting the truth. It is hard to depict the true appearance of a 3 dimensional moving person in a 2 dimensional static picture.[108]

Another important factor that is commonly brought up by those who don’t see portraits as a close representation of reality is that portraits are commissioned to artists. The subjects of the portraits or the commissioners had a big influence on the final painting as they funded the work. Different features of the subjects could be purposefully exaggerated in the process due to the customer’s request, so that the portrait is more flattering. [110] It is hard to tell which of the portraits of Napoleon Bonaparte is the most accurate, and they significantly differ. They were commissioned by different people with different attitudes to him and for different reasons and that is reflected in the variety of his portrayals. Some artist could convey own attitude to him through the painting, and that further distortes the reality.

Historic paintings that reached modern times significantly changed with time. That further distorts the potentially biased representation of the initial appearance of a person. Some portraits were reworked by other artists and restorers, and all went through chemical changes of the materials they were made of. Oil paint yellows with time, changing the original colours of paintings, for example the sky appears greener than it was originally painted, the skin becomes yellow. [111] Many pigments fade with time and if a certain detail in a painting was completed predominantly with those pigments, it may disappear with time. Old paintings were restored and cleaned multiple times, and that further altered them. For example it was discovered that most likely Mona Lisa originally had eyelashes and eyebrows but they either faded or were wiped away during restoration, completely changing the face.[112] Oil paintings were completed in multiple layers, and the top layers that normally contain details or tonal corrections were more likely to get damaged during restorations.

Truth in Photography

[edit | edit source]Nature of Photography

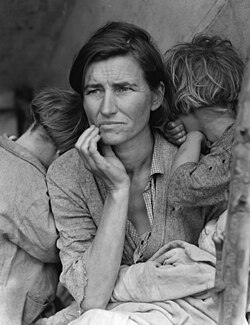

[edit | edit source]The nature of photography involving different parties allows it to consider different truth theories. Firstly, the correspondence theory of truth, the idea is what we say or believe is true if it corresponds to the way things actually are. [113] In this case, for a photographer to capture a moment, he will use his camera to take a shot – the shot taken is reflecting the way things are, thus truth here could be understood as what the photograph literally shows. Secondly, phenomenological approach to truth is concerned with the individual’s experience, this means that what one experiences is what is considered to be the truth. This follows that perhaps truth in photographs, lies within what the subject in the photograph experiences or what the individual viewing the photograph experiences. Lastly, the social constructionist perception argues that truth is derived from community consensus regarding ‘what is real’, ‘what is useful’ and ‘what is meaningful.’ [114] This means that the use of the photograph in a community could be what is regarded as the truth. Therefore, it is clear that photograph incorporates at least these three approaches to truth as it depends on the perception of the subject matter. This will be further demonstrated with the example of the ‘Migrant Mother’, a photograph captured in 1936 by Dorothea Lange.

Lange's Truth

[edit | edit source]Dorothea Lange was born in America and was known for her documentary photographs during the Great Depression as she worked for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Her works not only affected other people’s perception on the Depression-era but it also impacted the influence of documentary photography. [115] In 1936, Lange visited a pea picker’s farm and reached a small cluster of small tens where she approached the subject of the photograph – Florence Owens Thompson. Lange recalls that she ‘does not remember how (she) explained her presence or her camera… (Thompson) ask(ed) no questions.’ [116] To Lange the truth lies within what she sees when she took the shot – a mother roughly 32 years old living on frozen vegetables from the fields around her and the birds that the children killed. A mother who had to sell tires from her car to buy food. [117] Thus, the photo reflects a truth that poverty is a pressing issue that leads to hardship.

Thompson's Truth

[edit | edit source]The subject of the photograph, Thompson however has a different truth behind the behind the photograph. Thompson’s understanding was that these photographs would never be published [118] and one of her son’s claimed that it was impossible for them to sell car tiers because they ‘didn’t have any to sell.’ [119] The truth to Thompson is simply what life was to her – having 7 children and finding ways to support a family.

Society and Individual's Truth

[edit | edit source]In order for the photo to be published, Lange showed it to her superior – Roy Stryker, who found the photo special and had the urge to publish it. [120] The US government led by President Roosevelt at the time had several agencies to help people cope with the large scale unemployment. [121] By utilising the photographs produced by Lange, the congress located the people in need and legislated financial support for the people. [121] Hence, the truth of the photograph to the government or the society as a whole is reflecting the suffering people are experiencing but here it is extended to a wider context that seems to be applicable to a wider community. Moreover, through the means of publication, the effects of the Great Depression becomes more apparent.

For an individual looking into the photograph, the truth simply lies in what he sees which is the woman and 3 children. The expression of the woman’s face provokes thoughts for the audience, her eyes not looking into the camera could be interpreted as avoiding something or feeling ashamed. Whilst, her clothes could imply the living conditions. However, most shocking to an individual is the baby that the woman holds. It is so unnoticeable and so vulnerable that suggests the difficult times they live in.

Combination of Different Truths

[edit | edit source]By examining these different perspectives in dissecting truth in the photograph, it suggests that different truths can co-exist at the same time but it also demonstrates how the truth could be unclear. The clash in truth lies particularly in whether Lange’s account of her interaction with Thompson is the truth or whether Thompson and her son’s account was true. Meanwhile, the different parties’ perspective demonstrates the multiplicity of truth, that there is perhaps no one objective truth in photographer due to its nature of involving various people.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Gittler JB. Social ontology and the criteria for definitions in sociology. Sociometry. 1951 Dec 1;14(4):355-65.

- ↑ a b c Blaikie N, Priest J. Designing Social Research: The Logic of Anticipation. 3rd ed. Polity Press; 2019.

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235102122_What_is_Social_Constructionism 39-41

- ↑ Plato., Allan D. Republic. London: Bristol Classical Press; 1993.

- ↑ Grix J. Introducing students to the generic terminology of social research. Politics. 2002 Sep;22(3):175-86.

- ↑ Van-Inwagen P, Sullivan M. Metaphysics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) [Internet]. Plato.stanford.edu. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/metaphysics/#WorMetConMet

- ↑ Paul G, Rolf-Peter H. Idealism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) [Internet]. Plato.stanford.edu. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/idealism/

- ↑ Alexander Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University} M. Realism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) [Internet]. Plato.stanford.edu. 2019 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/realism/

- ↑ Woodruff D, Smith. Phenomenology (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) [Internet]. Plato.stanford.edu. 2018 [cited 10 November 2020]. Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/#:~:text=Phenomenology%20is%20the%20study%20of,of%20or%20about%20some%20object.

- ↑ Nakkeeran N. Knowledge, truth, and social reality: An introductory note on qualitative research. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2010;35(3):379.

- ↑ Sociology and Social Justice [Internet]. American Sociological Association. 2019 [cited 5 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.asanet.org/press-center/press-releases/sociology-and-social-justice

- ↑ a b Browne K. An Introduction to Sociology. 3rd ed. Polity Press; 2005.

- ↑ a b Roche S. [Internet]. Citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. 2020 [cited 10 November 2020]. Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.892.2886&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- ↑ a b Cooper F, Brubaker R. Beyond "Identity" [Internet]. Jstor. 2000 [cited 10 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3108478?seq=4#metadata_info_tab_contents

- ↑ Thatcher A. God, sex, and gender.

- ↑ Viloria H. The spectrum of sex: The Science of Male, Female, and Intersex; 2020

- ↑ a b Laqueur TW. Making sex: Body and gender from the Greeks to Freud. Harvard University Press; 1992.

- ↑ Delphy C, Leonard D. Close to home : a materialist analysis of women's oppression; translated & edited by Diana Leonard. Hutchinson; 1984.

- ↑ Rahman M, Witz A. What Really Matters?: The Elusive Quality of the Material in Feminist Thought. Feminist Theory. 2003;4(3):243-261.

- ↑ Harrison K. Objectivist and essentialist ontologies of gender & love. 2014;.

- ↑ Weinrich J. Reality or Social Construction?. In: Stein E, ed. by. Forms of Desire: Sexual Orientation and the Social Constructionist Controversy. New York: Routledge; 1992.

- ↑ Vance C. Pleasure and danger. London: Pandora Press; 1992.

- ↑ Branaman A. Introduction to Part I. In: Branaman A, ed. by. Self and Society. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2001.

- ↑ Thomas W, Thomas D. The child in America. New York, N.Y.: Alfred A. Knopf; 1928.

- ↑ Brickell C. The sociological construction of gender and sexuality. The Sociological Review. 2006 Feb;54(1):87-113.

- ↑ Cunningham M. Changing Attitudes toward the Male Breadwinner, Female Homemaker Family Model: Influences of Women's Employment and Education over the Lifecourse on JSTOR [Internet]. Jstor.org. 2008 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20430858

- ↑ a b c d Popov A, Parker L, Seath D. IB diploma programme. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017.

- ↑ Stets J, Burke P. Femininity/Masculinity | Encyclopedia.com [Internet]. Encyclopedia.com. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/femininitymasculinity

- ↑ Tinklin T, Croxford L, Ducklin A, Frame B. Gender and attitudes to work and family roles: the views of young people at the millennium [Internet]. Ces.ed.ac.uk. 2005 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: http://www.ces.ed.ac.uk/PDF%20Files/TT_0214.pdf

- ↑ MacGill M, Murrell D. Testosterone: Functions, deficiencies, and supplements [Internet]. Medicalnewstoday.com. 2019 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/276013#what-is-testosterone

- ↑ Hines M, Brook C, Conway G. Androgen and psychosexual development: Core gender identity, sexual orientation, and recalled childhood gender role behavior in women and men with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41(1):75-81.

- ↑ Gender dysphoria [Internet]. nhs.uk. 2020 [cited 10 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/gender-dysphoria/#:~:text=Gender%20dysphoria%20is%20a%20term,harmful%20impact%20on%20daily%20life.

- ↑ https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter12-gender-sex-and-sexuality/

- ↑ spectrum of sex

- ↑ INTERNALIZATION | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary [Internet]. Dictionary.cambridge.org. 2020 [cited 10 November 2020]. Available from: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/internalization

- ↑ a b c d Ryle R. Questioning gender: A sociological exploration. 2011.

- ↑ Mcleod S. Albert Bandura | Social Learning Theory | Simply Psychology [Internet]. Simplypsychology.org. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html

- ↑ Mcleod S. Albert Bandura | Social Learning Theory | Simply Psychology [Internet]. Simplypsychology.org. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html

- ↑ Ruble D, Balaban T, Cooper J. Gender Constancy and the Effects of Sex-Typed Televised Toy Commercials. Child Development. 1981;52(2):667.

- ↑ Women and girls [Internet]. Right to Education Initiative. 2020 [cited 10 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.right-to-education.org/girlswomen

- ↑ Smith A, David J, Marsden P. Frequency of Prayer and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family, . Summary | General Social Survey 2008 Cross-Section and Panel Combined | Data Archive | The Association of Religion Data Archives [Internet]. Thearda.com. 2008 [cited 10 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/GSS08PAN.asp

- ↑ BEAUTY | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary [Internet]. Cambridge Dictionary. [cited 1 November 2020]. Available from: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/beauty

- ↑ a b Hagman G. Aesthetic Experience: Beauty, Creativity, and the Search for the Ideal. Amsterdam: Rodopi; 2011.

- ↑ Michelis G, Tisato F, Bene A, Bernini D. Arts and Technology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2013.

- ↑ a b Ishizu T, Zeki S. Toward A Brain-Based Theory of Beauty. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2011 [cited 3 November 2020];6(7):e21852. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0021852

- ↑ FitzGerald T, Seymour B, Dolan R. The Role of Human Orbitofrontal Cortex in Value Comparison for Incommensurable Objects. Journal of Neuroscience [Internet]. 2009 [cited 3 November 2020];29(26):8388-8395. Available from: https://www.jneurosci.org/content/29/26/8388.short

- ↑ Mascolo M. Beyond Objectivity and Subjectivity: The Intersubjective Foundations of Psychological Science. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science [Internet]. 2016 [cited 3 November 2020];50(4):543-554. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305698501_Beyond_Objectivity_and_Subjectivity_The_Intersubjective_Foundations_of_Psychological_Science