User:JREverest/sandbox/Approaches to Knowledge/Seminar group 1/Imperialism

Definition

[edit | edit source]Imperialism is advocacy of power expansion and dominating others through theories, practices and attitudes. The historical evidence of imperialism often includes conquering territories, economic and ideological control. [1]

Historical studies in general referred 'Imperialism' to European countries, especially Britain in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, focusing on their expansion and influence on other continents. Thus the word is often related to 'Colonialism'. Nevertheless, 'Colonialism' usually refers only the colonial form of alien rule, whereas Imperialism has a broader scale of meaning and exerts influences in different fields, such as the financial impact of France and Germany over the Russian and Ottoman Empires, British 'gunboat policy' and American 'dollar diplomacy'. [2] Therefore, the concept of 'Imperialism' is more dynamic, though these two words can be used interchangeably in some situations. [3]

History

[edit | edit source]Old Imperialism

[edit | edit source]Imperialism profoundly changed the world in the nineteenth century, though it began long before that. The period from the sixteenth to the beginning of nineteenth century is called Old Imperialism, during which European countries discovered the New World by trading, and settled in North and South America, and also Southeast Asia. The European traders cooperated with local rulers and residents in order to protect their interests. But in this period, the impact was limited. At the same time, as the Europe's commercial Revolution demanded more wealth and raw materials, the colonies gradually being built served the needs and thus developed. For example, by 1800 Great Britain owned the most colonial power in India, South Africa, and Australia. Colonialism showed declined in the beginning of the nineteenth century because of the Napoleonic War. Many countries began to concentrate on domestic affairs with the rise of nationalism and democracy, and thought the costs on colonies exceeded the benefits. However, the Industrial Revolution in the middle of nineteenth century gave the resurgence of ambitious power expansion. [4]

New Imperialism

[edit | edit source]A policy of imperialism known as New Imperialism was adapted by the West from the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth. Different from the Old Imperialism, it was triggered by a complex of factors including humanitarian, religious, military, political and economic, accompanying with the progression in scientific theories and technology. For instance, the expansion was partly stimulated by the western superiority over the 'backward' societies. The outcome was also different. The beginning of a global economy was established in which goods, money and technology were regulated orderly to benefit the West ensuring adequate resources and labor force. Imperialism had destructive effects on the culture and industry of colonies. It impeded the development of industry in colonies in order to gain advantages of their goods. The western traditions were imposed on colonies, and brought severe cultural clash, such as the rejection of foot-binding in China. The west also introduced medicine. Meanwhile, Imperialism provoked the international conflicts among western countries. [4]

Economics

[edit | edit source]Apart from the urging desire of territorial expansion, there was also an economic rivalry that existed between the Great Powers before World War I. In Britain, many discussed about the threat which German firms represented to the traditional British primacy in Europe. Amongst them, the author Ernest Edwin Williams published a book called ‘Made in Germany’ in 1986, in which he warned that England’s industrial supremacy was staggering to its fall, and according to him, this was largely due to the challenge which German competition represented to British business. In fact, after World War I, some historians had even suggested that Britain had seized the opportunity represented by the July crisis in 1914, only to precipitate a war against its chief economic rival in Europe, and thus to remove a threat to its own commercial primacy. While on the one hand, businessmen whose profits were directly threatened by German firms sounded like the most alarming, on the other hand, those who profited from dealings with Germany showed a lot of enthusiasm and eagerly pointed out the benefits of mutual trade. After all, the economic relation between these two nations was not a zero-sum game in which, for one to prosper, the other had to lose. As a matter of fact, Britain relied on Germany as much as it was threatened by it. German customers represented Britain’s second largest export market after the United States. But while businessmen were worried at the prospect of foreign competition, they were even more afraid about the general collapse in trade that the war would bring about. This was the case for the so-called ‘Merchants of death’, with arms manufacturers such as Schneider Creusot in France or Škoda in Austro-Hungary. These firms made considerable amounts of money through contracts with their governments to produce battleships, guns and other weapons of war. But they also prospered by selling armaments to foreign powers. Moreover, they were well-aware that whatever short-term profits would be made by war time, contracts would be more than offset by the loss of overseas markets due to the general disruption in trade caused by war. There was then, little enthusiasm amongst businessmen for war in 1914. Indeed, when for the first time since it had been established in 1801, the British government closed the London stock exchange on July the 31st 1914, there was panic among investors who were worried that they would be ruined by a general collapse of the world financial system. A delegation of investors even went to see David Lloyd Judge, the British treasury minister, imploring him to keep the United Kingdom out of any continental conflict. After the war, Loyd Judge wrote in his memoirs ‘There are those who pretend to believe that this was a war intrigued, organized and dictated by financiers who ascribed our actions in 1914 to the irritation produced by a growing jealousy of Germany's strength and prosperity. It is a foolish and ignorant libel to call this a financiers war’. In fact, money was a frightened and trembling thing. Money suffered the prospect of war.

International Relations

[edit | edit source]In the field on International Relations, imperialism is defined as being the dominance of one political community over another political community, with the weaker community is influenced by the strongest one and aims to serve the dominant powers' interests

Realism

[edit | edit source]Realism is a doctrine that goes back to Antiquity with thinkers such as Thucydides, but it really came into its own after WII in order to prevent major conflict. The realists believe war to be inevitable and thus believe we can only learn to manage a conflict and prepare for it. Realism is seen as a conservative theory, realists don’t want to change the world but they want to describe it.

Realism is about the rule of The Three Ss: Statism, Survival and Self-Help= Statism is the idea that the state is the supreme authority that must ensure it’s citizen’s security. Survival is the idea that all states must maximase their power in order to protect itself. And finally Self-help is the idea that, because there is no higher authority within the International Community, each states must rely on itself to ensure its safety.

Realism relies on four core assumptions: - Nature of humanity: Realists have a negative view of the human nature. They see human beings as self-centered and power hungry.

- Nature of politics: Realism focuses mainly on politics in spite of economics, social dynamics and religion. It also focuses on competition and mostly the competition between states to gain power. Indeed realists believe power to be the ultimate goal and believe it to be at the center of international dynamics.

- Nature of international System/Politics: Realists believe there isn’t a higher authority within the international system. Thus, the constant fight over power between different states would lead to anarchy.

- Calculation of strategy: Realists think states are rational and simply try to maximise their self-interest.

Liberalism

[edit | edit source]Liberalism within International Relations relates to how the structures and institutions in place within a society contain and mitigate the power of the state[5]

Additionally, it is an international relations theory that believes that all actors on the international stage can reach a peaceful world order through cooperation and discussions. It argues that "democratic process and institutions would break the power of the ruling elites and curb their propensity for violence" while "free trade and commerce would overcome the artificial barriers between individuals and unite them" [6].

President Obama used liberalism and the spread of individual rights and democratic ideals as the justification of invading the Middle East in his address at the United Nations General Assembly in New York [7]

International Relations Theory and Imperialism

[edit | edit source]International Relations has been criticized for being far too Western-focused and antiquated. Realism's core assumption of human selfishness is based on Western philosophy. Even the existence of human nature and pre-existing characteristics in humans has been questioned in recent years. Similarly, Liberalism's focus on the spread of individual freedoms and rights is quite Western. [8] The theories have been considered inadequate for applications in the Middle East and third world countries in Asia [9]. The application of Western theories on non-Western states in an International Relations academic field has been considered to be an extension of the United States' power on the entire world and the justification of encroachments of power in the Middle East (e.g. the Iraq War). Some Eastern countries are starting to design their own theories to counteract the spread of power on International politics from the West. Chinese academics have developed International Relations with Chinese characteristics. Japanese International Relations also includes five traditions that originate from their own culture. [10]

Liberalism and the Democratic Peace Theory, the idea that democracies are more peaceful [11] than their foreign counterparts, have been the justification for occupations of the West on the East and arguably, imperialism. In his speech to the UN assembly, President Obama declared that "The United States of America is prepared to use all elements of our power, including military force, to secure our core interests in the region" [12]. By 'core interests' he primarily means democracy and human rights so as to obtain global peace. This justification has come under harsh criticism as simply being an excuse to exercise military imperialism and spread the ideals of the Western World.

Education

[edit | edit source]Western school curriculums could come from a perspective of imperialism, as well as affected by the values that imperialism thrived upon.

History

[edit | edit source]History could often be taught from an imperialistic perspective. A branch of historiography in the United Kingdom belongs to the WHIG historians[13], who were the ones who saw the world through the lens of imperialism, often an upward trajectory from constitutional democracy, to imperialism, capitalism, and therefore the industrial revolution that made Britain the greatest country in the world. Such historians were generally teaching in the early - mid 20th Century, but their legacy lives on.

"It can easily be proved that, in our own land, the national wealth has, during at least six centuries, been almost uninterruptedly increasing; that it was greater in the Tudors than under the Plantagenets, it was greater under the Stuarts than under the Tudors [...] it was on the day of the Restoration than it was under the day when the long parliament met" [14]- Thomas Babington Macaulay, a WHIG historian of the 19th Century.

A common view of the WHIG historian is that; their history of the world starts with the rise of the Europeans from the middle ages right up until a 1st and a 3rd world existed[15], a view of Europe paving the way towards civilisation and a glorification of European domination of the world, with other places disregarded or simply a tool, background characters in telling the story of forefront European characters. Recently, a new generation of historians have risen up to call this effect 'orientalism', where the perspective of the inferiority of the East have prompted historians' disinterest in teaching/ researching it.

Historians such as Peter Frankopan and Jared Diamond have exposed this view in recent academia as well as in popular historical culture, with claims that civilisation is subjective[16], and that Western development depended more heavily on the developments of Africa and Asia, as well as long periods of history where Asia dominated the world stage and yet was overlooked by WHIG historians. Their work exposes the contrasting views that conventional history had and thus prompted new interpretations:

"While such countries may seem wild to us, these are no backwaters, no obscure wastelands. In fact the bridge between east and west is the very crossroads of civilisation. Far from being on the fringe of global affairs, these countries lie at its very centre- as they have done since the beginning of history [...] and yet, despite the importance of this part of the world, it has been forgotten by mainstream history."[17] -- Peter Frankopan, The Silk Roads, A New History of the World

Economics

[edit | edit source]An idea that is backed by imperialism is how capitalism is essential for a country to thrive. Traditional economics incorporates imperialism into the education of capitalism, upholding it as an equally important factor to a country thriving.

Economics over Ethics?

[edit | edit source]When economics was first introduced, it contained only normative elements, but through time detached itself from its ethical side, becoming a principally positive science. Recently, ethical-moral values have returned to business economics; more businesses around the world have adopted objectives like reducing poverty in disadvantaged areas of the world and preserving the environment. The divorce of ethics from economics was a result of the divisions between those who appreciated the benefits of ethical ideas to predictions of human behaviour and economic analysis and those who believed this culminated in imperialism in economics over morals. Only until recent times was ethics and morals ignored in economic analysis, even though game theory and behavioural economics have made progress of significant magnitude. Nevertheless, assumptions that economic agents are self-seeking and are unnerved by ethics continue to dominate the discipline of economics, providing overwhelming evidence that economics have imperialist elements.[18]

Mathematics

[edit | edit source]Mathematics is often considered to be a school subject least associated with imperialism[19]. Abstract mathematical ideas, such as how many degrees there are in a circle, are often thought to have no imperialist bias - they are fact. However, imperialism is prominent in how these ideas came about ie. how was it decided that we would use degrees and why do we need to know? It tends to transpire that even though the mathematical facts may be separate from imperialism, the ideas themselves came from a western school of thought and are spread through an imperialist education system.

Pythagoras' Theorem

[edit | edit source]The famous Pythagoras' theorem, named after the Greek mathematician Pythagoras, is named as the 'Gougu Theorem' in China, after what China believes it should be named after: an arithmetical book called Zhou Bi Suan Jing. In India, it is claimed that was where the original mathematicians discovered the theorem; a book called Baudhāyana Śulbasûtra (written 800 BCE) by mathematician Baudhayana that had described the Pythagorean Theorem, approximately 1000 years before Pythagoras was born[20].

International Baccalaureate Diploma Program (IBDP)

[edit | edit source]Geography

[edit | edit source]

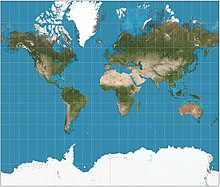

Imperialism has had a great impact on how we view the layout of the Earth. As Monmonier, 1994, p.21 states People's ideas of geography are not founded on actual facts but on Mercator's map. Maps are believed by many people to just be a social construction. The Mercator's map (1596) is used to help sailors navigate and also makes Europe look a lot bigger then it is. This map is seen to have an imperialist influence and is biased towards authorities and power within imperialism. The true size of Africa is actually a lot bigger then it appears on the Mercator Projection.[22][21]

A much more accurate representation of the Earth is the Peter's map. This shows Africa to be bigger, as it should be, taking up (30,3 million km2 ). However, this map again is still distorted and emphasises the continents with most imperialistic authority such as North America and Europe, leaving the other less wealthy countries to appear smaller then they really are[25][26]

The idea of North and South is also an Imperialistic influence of the way we look at the world. There no reason as to why the North and South are labelled as they are. The North is associated with goodness and wealth, whereas the South is associated with poverty, furthermore showing the impact Imperialism has had on Georgraphy and society's view of the world. McArthur's corrective map of the world shows an 'up-side down' map, going against the Imperialist influence on the maps that society sees as normal. [24]

However, it is noteworthy to add that the conventional perspective of the globe is conventional perhaps only in the Western world. Certain countries will put their own country in the middle of the map, naturally. One example would be how in Asia, the perspective of the world is different, with Southern Asia and China at centre.[27]

However, the generally accepted version is still the one impacted by imperialism.

Linguistic

[edit | edit source]the influence of power expansion can be seen on zones of contact, which were meant by various human differences interlinked with language diversity. Colonial agents realised the significance of overcoming the linguistic differences by practicing verbal communication, though remaining at a primary stage. Colonialists required 'languages of colonel command' to convey their orders, ideas and threats to all their colonies with a wide distribution. So linguistic texts over four hundred years were generated including such as grammars, dictionaries. These modern forms of structure and content made languages object to knowledge and thus the speakers subject to imperial power. Therefore, whatever approaches they adapted, linguists can be considered as colonial agents, and involved in the generation of human hierarchies.[28]

The massive imperialist epoch has ended, but as one of its branch, linguistic imperialism continues. Scholars divided the studies about the connection between imperialism and language into two categories, Missionary Linguistics (ML) and Colonial Linguistics (CL). Missionary linguists refer to those dedicated their time and energy to describing the indigenous languages of the colonies of the imperial powers. For example, in the Old Imperialism from late fifteenth century to early nineteenth century, missionaries were significant supporters for the linguistic projects launched by and beyond the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empire. In contrast, CL is not simply a non-missionary version of ML. Instead, in a postcolonial and global-historical way, Colonial Linguists can reconstruct the goals and synthesise them into a new context by broadening the horizontal. [29]

English

[edit | edit source]The popularisation of English learning in a global scale is noticeable and perceived as a process of linguistic imperialism which is a key component of continuous cultural and social imperialism. This language learning has been institutionalised and involves the exposure to the corresponding culture, in which sense, tagged as 'an imperialist structure of exploitation of one society or collectively by another'[30] and the worries about its negative impacts on the diversity of languages and cultures have also been raised. Because of the colonised experience, in many countries, English took place of their indigenous languages. For example, even after the status of Chamorro was recognised officially in 1974, English plays no less important role among the residents. Some scholars argue that the official and local exportation of learning aids and the operation of language programmes are means of influence expansion. For Europe in particular, with the idea of integration being promoted and the application of English as language for political and economic affairs, the Anglo-American 'linguistic imperialism' becomes more permeable. [31]Therefore, currently English serves as multiple functions, namely, economic-reproductive function, ideological function and repressive function as citizens are forced to learn and use it. It is unlikely to regard English simply as communication tool without connotations and the imperial power within the English learning will be maintained. There is a demand for Educators, administrators and researchers to evaluate this influence and reconsider their practices. [32]

Cultural and Social Anthropology

[edit | edit source]In anthropology, an academic discipline which was born and raised in the age of mass-scale colonialism and European imperialism, historical process and context is vital. Talal Asad writes in his ‘Afterword from the History of Colonial Anthropology to the Anthropology of Western Hegemony’ of “European Imperial dominance not as a temporary repression of subject populations, but as an irrevocable process of transmutation, (…) a story of change without historical precedent in its speed, global scope, and pervasiveness”.[33] Anthropologists are aware of the omnipresent influence of imperialism not only on the studied populations, but also on the way their discipline is shaped.

Although anthropology was not very useful for the advancement of imperialism (the research anthropologists gathered was considered too specific and abstruse, and therefore was often neglected by the European colonialists, who would regardless tend to aim to “civilise” the conquered societies leading them in a “modern” direction), colonialism and imperialism were extremely useful for the development of anthropology. They supplied anthropologists with new subjects of study and gave them the possibility to do fieldwork, ethnography being the most important research method in the discipline, in the most remote locations for considerable amounts of time. This opened many doors for growth in the discipline and provided the researchers with an important first question of what the non-European traditional, cultural and societal forms are, and how they are subject to “modern” change.[34]

The development of the discipline and various trends which were developing amongst its intellectuals over time give a good overview of the influence that imperialism had on anthropology as an academic subject. In the 19th century, when Europe was expanding to become the empire of the world, the evolutionary approach had become the most commonly widespread in anthropological research. Evolutionary anthropology tried to explain the diversity of the world’s peoples through theories of social progression by constructing a backward ‘phylogeny’ of social progress. Influenced by enlightenment rationalist theories that all humans are rational by nature, and due to this rationality societies will progress, as well as Darwin’s theory of natural selection, evolutionary anthropologists believed that society undergoes developmental processes similar to biological ones, and is thus constantly evolving towards being more civilised and complex. The primitive societies of the New World were therefore seen as examples of underdeveloped societies, which could be pushed to develop faster in order to start resembling the highly evolved western civilisations. Evolutionary anthropology shaped the imperialist view of the ‘savage’ societies in the newly discovered parts of the world and explains why colonisers placed such importance on attempting to impose western customs and beliefs on them.[35]

However, this view changed in the 20th century, with the influence of Jean Jacques Rousseau, who spoke of “Noble Savagery”, swaying the European intellectuals to his stance that there is happiness and nobility in primitive societies. Therefore the primitive begun to be associated with perfection, connection to nature, peace and tranquillity, while civilised Europe with violence, inequality, spiritual poverty and detachment from nature.[36] Imperialism was condemned and there was a rise of ethnologists, a new type of anthropologists who devoted years to do fieldwork living amongst primitive societies. One of the main consequences of 20th century anthropologists romanticising the primitive was that they portrayed them as static and frozen in time, as societies without history in a state of ordered anarchy, thus creating a very strong contrast between them and the Western civilisations shaped by centuries of history and with very imposing social and political order.[37] This is due to them failing, or consciously avoiding to acknowledge the immense influence that European imperialism had on the places they studied. For example, the Nuer hunter-gatherers in East Africa were seen as a stateless society in an ordered anarchy[38], but it was not acknowledged that they were nevertheless governed by the Anglo-Egyptian state and under imperial rule. They owed tax to the government (although they were allowed to pay it in cattle) and had to be obedient to the state, otherwise they would face punishment or execution determined by the local court governed by western legislation. This condition obviously had an effect on the Nuer people, who only superficially seemed completely autonomous within their society, but were actually conditioned and regulated by the European colonial powers. These influences could explain why the Nuer seemed so ordered in their society despite not having an official state, to anthropologists such as Max Gluckmann who were studying them in the mid-20th century.[39]

This was not just the case with the Nuer tribe, imperialism caused the traditional way of life to blur with new incoming customs from the colonial powers in all the places it expanded to. Many traditions were abandoned because new ones, which were perhaps more convenient and effective, were introduced (for instance metal roofs made of tin replaced the traditional thatched ones in Fijian villages), some were strengthened due to rebellion against the impositions of the imperial rule (in Fiji that was the case with the communal lifestyle of the native people) and many new customs were conceived into the culture as traditional (for example the Fijian boomerangs[40])[41]. The cultural shifts imperialism caused across the world were immense. It is partially because of this that, Asad points out, “much of what appears ancient, integrated, and in need of preservation against the disruptive impact of modern social change is itself recently invented”.[42] Even now the historical heritage of imperialism plays a huge role on how people view culture and society. A more recent example would be the spread of Islamic tradition in the middle-east, and the need of European social scientists to find a justification for it. The desire to explain such developments in tradition as anomalies in the modernising world shows the remains of the hegemonic approach engraved into western societies by imperialism. When places were Europeanised, it was considered normal and natural, and thus did not have to be explained but rather described, however when other cultures begin to spread a similar way, there is a desire to explain it as a cultural phenomenon.[43]

Imperialism spawned and shaped anthropology as an academic discipline; it was present through its development and still plays a huge role in the way cultures are understood and studied nowadays. It is, however, important to mention that the influence imperialism has in this field is increasingly acknowledged and taken into consideration in research and studies. Imperial history is constantly used to understand western culture and society as well as the influence it had on the colonised areas, and consciously referenced in anthropological discussion.

Globalisaiton

[edit | edit source]Globalisation is a complex concept which describes the interconnected economy and society. It is characterised by [44]:

- Acceptance of a set of economic rules to transition to universalising markets and production

- Technological innovation and organisational change centred on flexibilisation and adaptability

- Transfer to trans-national organisations of the control of national economic policy instruments

Globalisation is led by imperialism. Globalisation of economy is overpowered by the developed nations. Taking economic globalisation as an example, firms and organisations that are already established enter emerging markets.

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica, Accessed at 01/11/18[1]

- ↑ Smith, Simon C.(2015) History of Imperialism, International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences, pp. 685-691.

- ↑ Stuchtey, Benedikt(2011) Colonialism and Imperialism, 1450-1950, Mainz: IEG[2]

- ↑ a b The age of Imperialism 1870-1914, Accessed at 01/11/18[3]

- ↑ J W. Meiser, Introducing Liberalism in International Relations Theory, E-International Relations Students, 18/02/2018. Accessed online on 13/11/2018

- ↑ http://internationalrelations.org/liberalismpluralism/

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/transcript-president-obamas-speech-at-the-un-general-assembly/2013/09/24/64d5b386-2522-11e3-ad0d-b7c8d2a594b9_print.html

- ↑ http://www.sunypress.edu/p-4050-imperialism-and-internationalis.aspx

- ↑ Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. 2007. "Why is there no non-Western IR theory: reflection on and from Asia." International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 285-286. Ashworth, Lucian M. 2002.

- ↑ 2010. "Why theorize international relations." In International Relations Theory: A New Introduction, by Knud Erik Jorgensen, 6-32. R=Baskingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756223/obo-9780199756223-0014.xml

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/transcript-president-obamas-speech-at-the-un-general-assembly/2013/09/24/64d5b386-2522-11e3-ad0d-b7c8d2a594b9_print.html

- ↑ https://www.hist.cam.ac.uk/prospective-undergrads/virtual-classroom/secondary-source-exercises/sources-whig

- ↑ Thomas Babington Macaulay History of England(London: Heron Books, 1967; first published 1848) pp.219-221

- ↑ The Silk Roads, A New History of the World, Peter Frankopan pages 1-10

- ↑ Guns, Germs and Steel: a short history of everybody for the last 13,000 years, Jared Diamond pages 12-13

- ↑ The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, Peter Frankopan Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015. pages xv-xvi

- ↑ Zaratiegui, J.M., 1999. The Imperialism of Economics Over Ethics. Journal of Markets and Morality.

- ↑ Alan J. Bishop, Western mathematics: the secret weapon of cultural imperialism, Race Class 1990; 32; 51

- ↑ https://mysteriesexplored.wordpress.com/2011/08/31/baudhayana-pythagoras-theorem-world-guru-of-mathematics-part-8/

- ↑ a b By Strebe - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16115307

- ↑ http://sociologyinfocus.com/2014/03/your-map-is-racist-and-heres-how/

- ↑ By Strebe - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16115242

- ↑ a b By Poulpy, from a work by jimht at shaw dot ca, modified by Rodrigocd - self-made, from Image:Earthmap1000x500compac.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3692020

- ↑ http://uk.businessinsider.com/boston-school-gall-peters-map-also-wrong-mercator-2017-3

- ↑ By Strebe - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16115242

- ↑ http://projectavalon.net/forum4/archive/index.php/t-64957.html?s=54db22bd0394531162c1a9a35fe8fa56

- ↑ Errington, Joseph (2008) Linguistics in a colonial world: a story of language, meaning, and power, Online ISBN: 9780470690765[4]

- ↑ Stolz, Thomas and Warnke, Ingo H. (2015) Colonialism and missionary linguistics, ISBN: 978-3-11-040316-9[5]

- ↑ Phillipson, R.(1992) Linguistic Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Modiano, M. (2001) 'Linguistic imperialism, cultural integrity, and EIL', ELT Journal, 55(4), pp. 339-347.[6]

- ↑ Thomas Ricento (1994) Teacher of English to speakers of other language, Inc. (TESOL): review of Linguistic Imperialism by Robert Phillipson[7]

- ↑ Talal Asad, 1991, "Afterword: From the History of Colonial Anthropology to the Anthropology of Western Hegemony" in Colonial Situations: Essays on the Contextualization of Ethnographic Knowledge, p.314

- ↑ Talal Asad, 1991, "Afterword: From the History of Colonial Anthropology to the Anthropology of Western Hegemony" in Colonial Situations: Essays on the Contextualization of Ethnographic Knowledge

- ↑ Dr Allen Abramson, 08/10/2018, lecture on "Anthropology and the Idea of the Primitive"

- ↑ Rousseau, J.J., Philip, F., & Coleman, P. (1999). Discourse on the origin of inequality, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ↑ M. Sahlins, 1972, “The Original Affluent Society” in Stone-Age Economics, accessed online 01/11/2018 at [8]

- ↑ M. Gluckman, 1959, “The Peace in the Feud”, pp1-14 in Custom and Conflict in Africa, accessed online 01/11/2018 at [9]

- ↑ Dr Allen Abramson, 15/10/2018, lecture on "Structure, Event & Process: Relations between Social & Cultural Anthropology and History"

- ↑ Dr Allen Abramson, 15/10/2018, lecture on "Structure, Event & Process: Relations between Social & Cultural Anthropology and History"

- ↑ N. Thomas, 1997, “Tin and thatch”, pp171-185 in In Oceania: Visions, Artefacts, Histories, Duke University Press, accessed online 01/11/2018 at [10]

- ↑ Talal Asad, 1991, "Afterword: From the History of Colonial Anthropology to the Anthropology of Western Hegemony" in Colonial Situations: Essays on the Contextualization of Ethnographic Knowledge, p.316

- ↑ Talal Asad, 1991, "Afterword: From the History of Colonial Anthropology to the Anthropology of Western Hegemony" in Colonial Situations: Essays on the Contextualization of Ethnographic Knowledge, p.317-318

- ↑ http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/international-migration/glossary/globalisation/