User:HMaloigne/sandbox/Approaches to Knowledge/2020-21/Seminar group 17/Power

Power in the Copernican Revolution

[edit | edit source]These days, it’s common knowledge that the sun is the centre of our solar system, and all other planets revolve around it. But like many other of our modern-day truths, this has historically not always been considered correct model. The Copernican revolution was the paradigm shift away from the old geocentric model.

Power of Prior Knowledge Bias

[edit | edit source]

Prior to the introduction of the heliocentric system by Copernicus and Galileo, the geocentric system had been believed to be true. This system was developed by Alexandrian astronomer Ptolemy in 150CE,[1] and supported by Aristotle. It was only natural that people would be hesitant to renounce truths that had been established more than a millennium ago in favour of a radical new theory. Nicolaus Copernicus only published his De Revolutionibus in 1543, the year of his death, despite him likely having completed it earlier.[2] His hesitation in publishing might have stemmed from the power of public opinion.

Power of the Roman Catholic Church

[edit | edit source]In the 15th and 16th century, the majority of the European population were Christian. That meant that the church and the bible had a great influence on public opinion. Major reasons for the church being against the heliocentric theory included:

- Heliocentrism contradicted multiple passages of the Bible. An often mentioned passage is Joshua 10:11-13, in which the Lord pauses the sun and the moon. The interpretation of this passage at that time was that it implied that the sun and the moon both orbited around the earth.

- Aristotelian theory founded the basis for most of the church’s theological and scientific beliefs. This is most evident in the theology of Thomas Aquinas, often seen as the greatest medieval christian thinker.[3] Aristotle himself was an adamant believer of the ptolemaic theory. This meant that Copernican theory directly challenged the authority of the church’s scientific beliefs.

Initially, the church allowed Copernicus’ book to be published. However, as the implications of it became clear, they chose to add it to their List of Prohibited Books (commonly referred to as the Index), which meant that the book could not be published and people in possession of it were trialed.

Power of Language

[edit | edit source]As mentioned before, Copernicus’ book De Revolutionibus was initially not added to the index. This was in part achieved through the use of language by Lutherian clergyman Andreas Osiander. Osiander rejected Copernicus’ thoughts, and added the following two parts:

- He added an anonymous preface, in which he wrote that Copernicus’ hypotheses “need not be true nor even probable”.[4]

- He changed the original name “On the Revolutions of the Orbs of the World” into “On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres”.[4]

These both would have mitigated the claims that Copernicus made in describing the “real” universe.

How Power is Utilised within Dom/Sub Relationships in BDSM

[edit | edit source]In Sexuality Studies, power can be appraised in the context of kink (sexuality), specifically BDSM. The recurring theme of power in these phenomena provides an opportunity for the role of power in interpersonal relations and the way it can be asserted or relinquished for gratification to be unearthed. In broad terms, BDSM as a subculture and a practice is a characterised by bondage, discipline, sadism and masochism, often in an erotic context.[5] Of the many concepts in BDSM, dominant and submissive or master and slave relationships are common [6]. These entail a dynamic in which one or more individuals holds a position of power or authority over one or more individuals who hold a position of weakness or subservience.[5] This inequality of power is at the core of BDSM and the means through which individuals are gratified within this community [7].

In this way, power in dominant/submissive relationships may appear as direct coercion, the wielding of the power one has over others to get them to do something they would otherwise not do [8]. Yet, unlike political or embedded social power, power in BDSM is transient and fluid, governed by a safe word and mediated through communication and mutual respect [9]. As such, power in BDSM is more closely related to Foucault's description of power as a strategy, rather than something to be possessed and utilised [10]. BDSM practitioners perform a role, either in 'scenes' or in their lifestyle more widely, and embody the power warranted by that identity through specific strategies.

What research has been conducted so far on BDSM has tended to focus on psychological characteristics of those engaging in the lifestyle or practices. Despite common assumptions that engaging in BDSM corresponds with sexual dysfunction or disorder, several studies have found the opposite to be true. Measuring various markers of psychological well-being, including the Big Five personality dimensions test [11], attachment styles questionnaires and psychometric measures of psychopathy, researchers found no higher prevalence of psychopathy in BDSM practitioners when compared to the controls.[12][13] This suggests that the giving or taking of power in interpersonal dynamics, when consensual and to some extent performative, has no injurious effects on those involved, nor is it a product of existing mental or emotional imbalance.

The proximity of BDSM practices to those presented in sexual sadism disorder and sexual masochism disorders however, suggests a complexity in separating sexual order from sexual disorder. So much so that there is no rigid definition of what are considered ‘unusual’ sexual behaviours and what are considered paraphilic - or worthy of note in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or International Classification of Diseases [14]. The power dynamics involved in those disorders listed above therefore potentially call into question the relationship between maladaptive conceptions or notions of power and sexual or mental disorder.

Issue of Power in Classical Music

[edit | edit source]The issue of power in classical music is expressed through gender inequality. Historically, it was highly influential for the career opportunities of women in classical music, this also has played a huge role in shaping the gender imbalance in today’s classical music landscape.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century, women’s participation in classical music was limited to those with high social status. Performances only happened in private, often where a correspondent supportive network was given. This is because certain instruments were considered to be too challenging for women to master or the positions in which instruments, such as the cello are played gave them an ‘unladylike’ appearance.[15] Due to these considerations, women had very limited access to music education, or were even entirely excluded from it.[16]

The most dominant orchestras at that time didn’t recruit female musicians. The only option to participate was in female only orchestras, which were usually of much less significance. It was not until World War II where the major shortage of male musicians finally granted women seats in these orchestras, although the recognition for females in these orchestras only happened slowly. An extreme example is the Vienna Philharmonic which only began host female auditions from 1997.[17]

Studies have shown that a significant gender gap is still manifested in classical music today. In 2019, less than 6% of the pieces played by orchestras were composed by females, moreover, there are almost no female conductors in European orchestras. Nowadays, efforts are being made to address the gender imbalance in classical music, such as the establishment of blind auditions, mentorship opportunities for females or the commitment towards an equal distribution in orchestral seats.[18]

Issues of Power in Education

[edit | edit source]Education, being at its core the transfer of collected knowledge from certain individuals to others, naturally manifests power in different forms and across different areas of the education systems. From education policy to classroom dynamics, power influences how students come into contact with their content of study.

Authority and influence are two categories for which most forms of power in education can assimilate under:

- Authority: This refers to the hierarchical power of revered decision makers, be them governmental education ministers and policy makers or heads of schools. The decisions of these authoritative figures directly influences the content and format of the education student's receive.[19]

An example of use of authoritative power in education would be when education in the UK became compulsory up to the age of 10, under an 1880 Education Act under The 1870 Education Act. This act used the power of government to enforce children's attendance at primary schools, potentially changing the future lives of many UK children.[20]

- Influence: This category of power refers more to the variable relationships that can form within groups of educational systems, these occur through covert decision making such as manipulation, favouritism, and other general influencing factors in human relationships.[19]

An example of influential power in education systems is the psychological theory of Teacher Bias developed by Robert Rosenthal in the 1960's; the study evidenced that teacher's have a natural tendency to hold differing expectations of students based on race, gender, handwriting, and other factors; and these predisposed expectations affect the student's educational performance accordingly.[21]

Power in the Indian Caste System

[edit | edit source]The Caste System by itself is not a discipline but is an area of interest and research in social and cultural studies as well as sociology and anthropology. The Caste System in India by itself is a very complicated, structured and divisive subject which impacts the people in the country in a lot of ways. The manifestation of power in this social system is a very prevalent one as it is seen in policies, education, social mobility, violence and many other ways.

Caste is a complex and rigid form of social stratification, originating from ancient Indian society, which classifies individuals in terms of hereditary occupations. The classifications are in four distinct groups: Brahmins (the priests and the educators), Kshatriyas (the warriors), Vaishyas (the merchants) and the Shudras/ Dalits (the commoners).The fifth group called the "Dalits" aren't included in the Varna system as they are deemed "impure' and thus "casteless".[22] Caste is assigned at birth, depending on the parentage and follows a hierarchy which shapes social interaction, ideas of “honor” and “purity” as well as individual social mobility. Though it is central to early Vedic Hindu society, similar caste systems have been seen in other South Asian and Polynesian regions.

Due to it’s largely hierarchical nature, power plays an important role in understanding the caste system and manifests itself in multiple ways. There is a clear division between Brahmins, Kshatriyas (known as the savarnas) and the Vaishyas/Shudras (known as the avarnas). There is a disproportionate amount of animosity directed towards the Dalits, as they are also labelled as “the Untouchables”. Despite the caste-system being abolished in the 1950s, there is still a large disparity and a caste based power dynamic still exists and affects those who are “of lower caste” and provides social capital or privilege to those “of higher caste”.

Direct Power and the Caste

[edit | edit source]Direct power can be defined as “getting someone to do something they wouldn’t otherwise” or having a specific form of influence or dominance over another group. An example of how direct power manifests itself in the caste system in caste-based violence towards the Dalits. According to National Crime Bureau Statistics, in 2016, over 40,801 atrocities against Dalits were recorded.[23]

Indirect Power and the Caste

[edit | edit source]A reason why most of these atrocities against Dalits often aren’t investigated is because of the political and social systems in place which favor the Upper Castes. The caste system is deeply rooted in the religious teachings of Hinduism and that is reflected in social systems and institutionalisation which creates disparity in the lower caste.[24] An example of this “indirect power” could be the education system in India. Most well funded and “English medium” schools in India are privatised. A majority of Dalit children depend on public schools for education, which are underfunded and do not provide the same social capital to students as a private school. This traps Dalits into a cycle where they are unable to progress as systemic caste-ism makes it more difficult to attain upward social mobility.[25]

Another example of Indirect Power in caste would be seen as “power of non-decision making”, where many upper and middle class Indians believe that the Caste system no longer exists as they themselves haven’t had any experiences of their own. This denial of its existence is also present in multiple international Indian diasporas where caste based atrocities by Indians is not recognised. An example of this is how British-Dalits have been rallying for protection against caste based discrimination but have faced opposition from different religious and political groups.[26]

Issue of Power in Protesting Against Anti-abortion Laws

[edit | edit source]

Protests against the tightening of anti-abortion laws in Poland began in October 2020 after the Constitutional Court ruled that the possibility of an abortion due to a severe and irreversible impairment of the fetus or an incurable life-threatening illness is unconstitutional.[27] These were the biggest mass protests in Poland since the political changes in 1989.[28] The protests were widely commented on in the international media and over one hundred cities around the world had joined the women's strike. Such spectacular notability could be explained through the concept of power.

Power of Gender Inequality

[edit | edit source]Polish politics is dominated by men. Currently, there are 460 MPs in the Polish parliament and only 134 of them are women which makes up roughly 29% of members. The Constitutional Court comprises of 15 judges among which there are only 2 women.[29] The members of the ruling party Law and Justice, who appoint judges to the Court and are the originators and promotors of the anti-abortion laws, are 76% men. Life and rights of almost 20 million women and their future children depend on views and decisions of 13 men. This political dynamics shows that not only power of gender is utilised in legalisation but also the power of authority body.

Power of Language

[edit | edit source]The women's strike organisers were straightforward and clearly defined their goals. Most of the slogans were based on short and uncensored insults directed at the ruling party. The protesters followed their example very quickly and millions of Poles have been fighting for women's rights ever since, using common slogans and symbols that appeared on the banners. The red lightning trend has been disseminated through social media and thus recognised as a national symbol of the protesters. What is more, the promoters of the abortion rights movement, thanks to their persuasive and strictly established demands, were able to convince millions of people to strike, block the traffic in the Polish capital, cause a decrease in the support of the ruling party and, most importantly, declare more drastic ultimata such as the resignation of the party leader.[30]

The Issue of Power in Archaeology

[edit | edit source]Archaeology is the scientific study of the material remaining from past human life and activities. Archeologist's research takes two forms of out-of-doors fieldwork: field work and excavation. Indeed, the conservation of archeologist sites is key to the studies of culture and study of past lives. [31]

Archaeology and Colonialism

[edit | edit source]Nowadays, many archeological objects coming from all around the world can be found in western museums. Indeed, the colonial history of western countries has permitted Archeologists to transport artefacts from their original location to western institutions. The image given to archeology during the 20th century has been falsified in order to justify the culture appropriation that was taking place. [32]This appropriation of culture was justified by Europeans by claiming that without their protection, these objects are threatened to disappear. [33]

The term 'Colonial discourse' or 'discourse of civilization' has been used by several scholars to describe the condescending attitude of the colonizers toward the colonized people. Indeed, according to this, Western colonial powers took and still take the responsibility to protect non-western cultures, hence assuming that they are not capable of doing it themselves. [34] [35]

The Example of Egypt

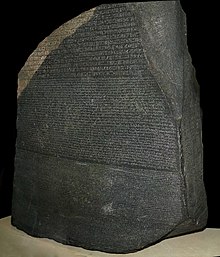

Egyptology is a discipline focused on study of ancient Egypt in several aspect notably archaeology. It was created in the 18th century when Napoléon Bonaparte invaded Egypt. Egyptologist were mainly western scholars for centuries, which is why until recently most of the discoveries were claimed by Europeans. However, a shift in these power dynamics is happening nowadays. The latest discovery of trove of treasures in the Al-Asasif Cemetery in Luxor was made by Egyptian excavators for the first time. Nowadays, an important amount of Egyptian ancient artefacts and pieces are exposed in western museums. However, Egyptian are fighting to gets its smuggled heritage back. Over the last years many objects have been sent back to their place of origin but some are still in discussion such as the Rosetta Stone which has been displayed at the British Museum in London for more than 200 years.

[36] Another impact of colonialism in the field of archaeology, in Egypt, is the question of the teaching language. Indeed, in this field, archeologist tend to communicate in English, French, and German with no consideration for the location and official language. This causes the exclusion Egyptian archeologists and maintains the power dynamic of colonialism. [37]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Jones A. Ptolemaic system [Internet]. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2020 [cited 7 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/science/Ptolemaic-system

- ↑ Westman R. Nicolaus Copernicus [Internet]. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2020 [cited 7 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nicolaus-Copernicus

- ↑ Emery G, Levering M. Aristotle in Aquinas's theology [internet]. Oxford University Press; 2015 [cited 7 November 2020]. Available from: https://oxford-universitypressscholarship-com.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198749639.001.0001/acprof-9780198749639

- ↑ a b MacLean R. De Revolutionibus [Internet]. Gla.ac.uk. 2008 [cited 7 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/apr2008.html

- ↑ a b Langdridge D, Barker M. Safe, sane and consensual. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2007

- ↑ De Neef N, Coppens V, Huys W, Morrens M. Bondage-Discipline, Dominance-Submission and Sadomasochism (BDSM) From an Integrative Biopsychosocial Perspective: A Systematic Review. Sexual Medicine. 2019;7(2):129-144.

- ↑ De Neef N, Coppens V, Huys W, Morrens M. Bondage-Discipline, Dominance-Submission and Sadomasochism (BDSM) From an Integrative Biopsychosocial Perspective: A Systematic Review. Sexual Medicine. 2019;7(2):129-144.

- ↑ Dahl R. The concept of power. Behavioral Science. 1957;2(3):201.

- ↑ Carlström C. BDSM, becoming and the flows of desire. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2018;21(4):404-415.

- ↑ FOUCAULT M. DISCIPLINE AND PUNISH. London, England: PENGUIN BOOKS; 2020.

- ↑ Wismeijer, A. and van Assen, M., 2013. Psychological Characteristics of BDSM Practitioners. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(8), pp.1943-1952

- ↑ Richters, J., De Visser, R., Rissel, C., Grulich, A. and Smith, A., 2008. Demographic and Psychosocial Features of Participants in Bondage and Discipline, “Sadomasochism” or Dominance and Submission (BDSM): Data from a National Survey. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(7), pp.1660-1668.

- ↑ Connolly P. Psychological Functioning of Bondage/Domination/Sado-Masochism (BDSM) Practitioners. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 2006;18(1):79-120.

- ↑ 11. Joyal C. How Anomalous Are Paraphilic Interests?. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(7):1241-1243.

- ↑ Clementina C. Gender and the Classical Music World: The Unaccomplished Professionalization of Women in Italy. Per Musi. [Internet]. 2019;39(July):1-24. [cited 5 November 2020]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.35699/2317-6377.2019.5270.

- ↑ Desmond C.S., Evangelos H. Orchestrated Sex: The Representation of Male and Female Musicians in World-Class Symphony Orchestras. Front. Psychol. [Internet]. 2019;10:1760. [cited 5 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01760/full

- ↑ Farah N. When an Orchestra Was No Place for a Woman. The New York Times International 23 Dec 2019; Sect. A:9

- ↑ Mark B. Female composers largely ignored by concert line-ups. The Guardian 2018 Jun 13;Sect. Music. [Internet]. [cited 5 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/jun/13/female-composers-largely-ignored-by-concert-line-ups

- ↑ a b Bolman LG, Deal TE. Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice, and Leadership. 5th ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2013.

- ↑ The Elementary Education Act, 1870 (c.75). [Online]. London: The Stationery Office. [Accessed 6 November 2020]. Available from: [1](http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/acts/1870-elementary-education-act.html)

- ↑ Rosenthal R, Jacobson L. Teachers’ Expectancies: Determinants of Pupils’ IQ Gains. Psychological Reports.; 1966

- ↑ Caste | Encyclopedia.com [Internet]. Encyclopedia.com. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences-and-law/anthropology-and-archaeology/anthropology-terms-and-concepts/caste#3

- ↑ Documenting Violence Against Dalits: One Assault At a Time | A News18.com Immersive [Internet]. News18. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.news18.com/news/immersive/documenting-violence-against-dalits-one-assault-at-a-time.html

- ↑ Mayell H. [Internet]. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/6/indias-untouchables-face-violence-discrimination/

- ↑ Nambissan G. Equity in Education? Schooling of Dalit Children in India. Economic and Political Weekly n. 1996;vol. 31(no. 16/17):1011-1024.

- ↑ Caste in Britain [Internet]. Economic and Political Weekly. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.epw.in/journal/2018/10/commentary/caste-britain.html

- ↑ "Poland's mass protests for abortion rights".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Notes from Poland".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Women in Parliaments".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "The Guardian on Polish protests".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Edmund Daniel, Glyn. "Archaeology". Britannica. Britannica. Retrieved 1974-81.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Moro-Abadía. "The History of Archaeology as a 'Colonial Discourse'". Bulletin of the History of Archaeology. Retrieved 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Degli Esposti, Emanuela. "Colonialism and archaeology: The legacy lives on". MEMO. MEMO. Retrieved 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "colonial discourse theory". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 2020.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Degli Esposti, Emanuela. "Colonialism and archaeology: The legacy lives on". MEMO. MEMO. Retrieved 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ El-Geressi, Yasmine. "Egypt Wants its Treasures Back Demands for Repatriation of Plundered Artifacts are Becoming Hard to Ignore". Majalla. Majalla. Retrieved 2019.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Watson, Sara Kiley. "Egypt is reclaiming its mummies and its past". Popular science. Popular science. Retrieved 2019.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Langer, Christian. "Informal Colonialism of Egyptology: The French Expedition to the Security State". E-International Relations. E-International Relations. Retrieved 2017.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)