User:Fadedglint/sandbox2

Biodiversity

[edit | edit source]Fauna of the Baja California Peninsula Sonoran Desert

[edit | edit source]Dermochelys Coriacea

[edit | edit source]The leatherback sea turtle is the largest of all living turtles and is the fourth-heaviest modern reptile behind three crocodiles. It is the only living species in the genus dermochelys and family dermochelyidae. The leatherback sea turtle can be easily differentiated from other modern sea turtles by its lack of a bony shell, hence the name. Instead, its carapace is covered by skin and oily flesh.

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]The Seri people, a tribe found in Mexico, find the leatherback sea turtle of significant cultural significance because it is one of their five main creators. The Seri people devote ceremonies and fiestas to the turtle when one is caught and then released back into the environment.

Ecological Trouble

[edit | edit source]Leatherbacks have slightly fewer human-related threats than other sea turtle species. Their flesh contains too much oil and fat to be considered palatable, reducing the demand. However, human activity still endangers leatherback turtles in direct and indirect ways. Directly, a few are caught for their meat by subsistence fisheries. Nests are raided by humans in places such as Southeast Asia. In the state of Florida, there have been 603 leatherback strandings between 1980 and 2014. Almost one-quarter (23.5%) of leatherback strandings are due to vessel-strike injuries, which is the highest cause of strandings.

The Seri people have noticed the drastic decline in turtle populations over the years and created a conservation movement to help this. The group, made up of both youth and elders from the tribe, is called Grupo Tortuguero Comaac. They use both traditional ecological knowledge and Western technology to help manage the turtle populations and protect the turtle's natural environment.

Antilocapra Americana Peninsularis

[edit | edit source]Antilocapra americana peninsularis, also known as the Baja California pronghorn, is a subspecies of pronghorn endemic to the Baja California Peninsula. Antilocapra americana peninsularis is a critically endangered subspecies according to the IUCN with only an estimated 200 animals remaining in the wild. This subspecies can stand up to 35 inches tall at the shoulder and weigh in at up to 125 pounds. These animal's coloration ranges from golden brown to tan, with white coloration on the jaws, stomach, rump and lower neck. The Baja California Pronghorn is often called los fantasmas del desierto which translates to, “ghosts of the desert,” because their particular coloration in combination with their fast speeds allows them to disappear in the desert. Furthermore, these animal's white underbellies deflect ground heat, keeping them cool. Females are smaller than males, and if horned, retain their spike-like horns for 2-5 years before shedding them. The larger males are longer horned than females, with darker faces. Males' horns are forward-pointing prongs below backward-facing hooks, and outer sheaths are shed annually. These animals are known to live roughly 9-10 years in the wild but may live longer in captivity.

Range

[edit | edit source]The Baja California pronghorn now only exists in the El Vizcaíno Desert Biosphere Reserve of Baja California and in the Valle de Los Cirios Reserve of Baja California, Mexico. The animals once roamed largely over central Baja California, including areas like the one east of Guerrero Negro named Llano del Berrendo, or Pronghorn Plains.

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]Baja California pronghorn have long-standing ties as a source of sustenance to people indigenous to Baja California. The animals, once widespread, were hunted with bows and arrows, eaten, and skinned to make women’s clothing. The indigenous people, the Cochimí, referred to them as ammo-gokio or ammogokió.

Additional Information

[edit | edit source]Antilocapra Americana Peninsularis is the fastest hoofed mammal in the world and the second-fastest land mammal. They possess the ability to run at 40-60 miles per hour for over an hour. With 27 foot strides at their top speeds, the Baja California Pronghorn has padded cloven hooves to absorb the resulting shock. When running these animals open their mouth and leave their tongue hanging to consume more air. Their windpipe can reach up to two inches in diameter, funneling air to their enlarged lungs and heart which aid them in oxygen consumption. This unique animal’s oxygen consumption is three times greater than that of comparably sized animals.

Baja California Pronghorn have remarkable eyesight and have the largest eyes of any hoofed animal in North America their size. They have the ability to see for miles. Their pupils can constrict into horizontal slits, which gives them 300-degree vision, protecting them from predators.

Threats and Conservation

[edit | edit source]The future for these animals remains uncertain. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists their conservation status as critically endangered. Livestock fencing and cattle ranching threaten their livelihood. These obstructions inhibit the animal’s access to favorable habitats and their ability to conduct natural movement. Urban sprawl, human endeavor, and droughts also all threaten populations.

In 1997, the Mexican Government, in cooperation with ENDESU (Espacios Naturales y Desarrollo Sustentable), established the Peninsular Pronghorn Recovery Project. This project, working in conjunction with zoos such as the Los Angeles' Zoo’s animal husbandry program, has grown the population of the Baja California Pronghorn to now exceed 420 animals, both captive and wild, in the areas of the El Vizcaíno Desert Biosphere Reserve and The Valle De Los Cirios Reserve.

Phocoena Sinus

[edit | edit source]This wonderful aquatic creature named Vaquita is under the Porpoises family which is a long group of marine animals that are mammals that are classified as Phocoenidae. Also the Vaquita, is an endemic animal, that is to say relevant of its location that receives its name “ Vaquita” which in Spanish means “little cow”. This species appears in the Gulf of Baja California and unfortunately is in danger of extinction.

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]The Vaquita is one of the few species of the porpoise endemic which means that it exists only one place in the planet. Because of this it can bring many tourists in the area for ecotourism which is environmental tourism that sees wildlife in its habitat. But because unfortunately the Vaquita is in danger of extinction it can negatively affect the cultural aspect of the areas surrounding the Gulf of Mexico.

Ecological Trouble

[edit | edit source]Unfortunately, the Vaquita is in danger to extinction. Because of this there will be fewer animals for both prey and predators many sea creatures will be affected by this in which the balance of the food chain in the Gulf of Mexico will have to change and adapt with the disappearance of this wonderful aquatic creature. Vaquitas usually eat around a dozen different type of small and medium-sized fish in which will have one less predator so their numbers can grow and affect the food chain there and also other larger species such as sharks were the Vaquita’s predator in which they will have one less food source again negatively affecting the food chain.

Ctenosaura Hemilopha

[edit | edit source]This animal is also known as the cape spinytail iguana. They are reptiles that eat mostly plants but they are also able to eat small animals and bugs if they are present. They live in trees, build dens, and sometimes even in cacti. Some people believe that they are in the locations they are today because the Seri Indian people brought them as a source of food. These animals are considered vulnerable because humans are taking over their natural habitat, sometimes they can be hunter to be sold as pets and dogs and cats can pose a threat to them as well. What I think is most surprising about these animals is that they coexist with another type of iguana which is not always common since there may be a limited amount of resources.

Flora of the Baja California Peninsula Sonoran Desert

[edit | edit source]Ficus Palmeri

[edit | edit source]Baja California has two native species of figs from the Moraceae Family: Ficus Palmeri, which grows from the Cape Region to the Tinaja de Yubay region, in Central Baja, many of the islands, and parts of Sonora; whereas, Ficus brandegeei has a smaller range from the Cape to a little north of Loreto, only. They are both pretty similar, with the largest difference being that the Ficus Palmeri does not display its branches and leaves with long ¨hairs¨, meanwhile the Ficus brandegeei does.

Both varieties are called Higuera ("Fig" in Spanish), Zalate or Amate ("you love you" in Spanish), or the Desert Fig in English.

Ecological Significance

[edit | edit source]The Baja Ficus grows usually on cliffs or in the cracks of rocks. Trees and plants such as the Ficus, help to breakdown or weather stone, creating soil in its wake. Ficus palmeri, as well as three species of cacti in the Baja region (Pachycereus pringlei, Stenocerueus thurberi, and Opuntia cholla) feed on dense layers of microscopic bacteria and fungus that cover the rock surfaces. Then release valuable minerals such as potassium, zinc, magnesium, copper, iron, manganese, and phosphorus during this chemical weathering process. This process provides an indispensable supply of inorganic nutrients for other plants that do grow in the soil.

In Baja, a tea made from the leaves and small branches is used as an antidote for rattlesnake bites in cattle and mules. A wash is used to treat cuts and infections. This is probably due to the fact that the milky white sap of this tree is natural latex that is toxic, a known allergen and is photosensitive. It is also shown to contain anti-inflammatory and antiseptic chemicals as well.

Fouquieria Columnaris

[edit | edit source]Fouqueria Coumnaris, also often referred to as a Boojum tree or Cirio tree, is a nearly endemic species of stem succulent tree found in the Baja California Peninsula. These trees have a single or branched tapered primary stem. Their primary stems are armored with hundreds of horizontal secondary branches that are not succulents and are armed with spines. When moisture is available to the tree, leaves and secondary branches may grow. However, the trees are usually leafless during arid periods. In relation to moisture received during winter and spring months, the Boojum will elongate its stem. The Boojum is known to bloom in late summer and autumn, bearing clusters of white fragrant flowers or creamy yellow flowers with a honey scent. The tree is a member of the ocotillo family. The Boojum is reported to grow up to 70 feet tall, with its trunk growing up to 24cm thick.

Range

[edit | edit source]Fouqueria Coumnaris is nearly endemic to the Baja California Peninsula. The tree grows with the help of moist, cool winds from the Pacific Ocean moderating the arid desert climate. The tree can be found in both upper and lower Baja, California. However, it is most commonly found in the subregion of Vizcaíno. Along the Gulf Coast of Sonora, a small population of Boojum exists with help from the cold waters that replicate the influence of the Pacific.

Name

[edit | edit source]The plant received its English name from the Southwestern naturalist Godfrey Sykes in 1922. When Sykes encountered the foreign-looking plants, he dubbed them “boojums,” a nod to Lewis Carroll’s poem The Hunting of the Snark. The Spanish name of Cirio, meaning candle, originates from the plant's long tapered look, similar to that of candles at nearby missions.

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]An indigenous group of people native to Sonora, the Seri, believe touching the Boojum tree will cause undesirable, strong winds to blow. Furthermore, botanists used to believe mainland patterns of distribution of the plant indicated that the Seri transplanted the boojum further in the interior. However, given the Seri belief about the Boojum, which they call cototaj, this belief has been called into question.

Additional Information

[edit | edit source]Fouqueria Coumnaris differs from its relatives in the ocotillo family by growing in the winter. Boojum trees were previously believed to only grow inches per year and reach up to 700 years old. Scientists now know that the plants can grow up to as much as 1 to 2 feet during a wet year. Additionally, repeated photography helped discover that the plants only typically live roughly a century. Large individual Boojum are particularly susceptible to direct hurricane events which cause significant destruction to the Boojum population every few decades.

Notable Boojum

[edit | edit source]The tallest Boojum on record was in Montevideo Canyon near Bahai de Los Angeles. It was recorded by Robert Humphrey in the 1970s and at the time, was 81 feet tall. Hurricane Nora passed directly over the large boojum in 1997, however, the mighty tree survived.

The University of Arizona recently had to remove one of its diseased Boojum trees. The tree was planted in the 1920s or 1930s after a University of Arizona sponsored Baja California trip. The specimen was a noted member of the Krutch Garden and, at 37 feet tall, one of the largest Boojum in the state. Nurserymen plan to attempt to clone the tree using its tips. This process will be documented and is an opportunity for botanists to evaluate opportunities and methods for cloning Boojums. If the precise genotype is successfully saved, it will be reintroduced into Krutch Gardens.

Threats and Conservation

[edit | edit source]Fouqueria Coumnaris trees are pollinated by many different insects. A study of over 20 years yielded a wide variety of species from the same Fouqueria Coumnaris trees in both Baja California and Sonora. However, many of these species of insects have not been seen again for many years. This may be caused by a temporal niche separation. Diverse types of pollinators have been recorded every year prompted by unknown environmental circumstances in which further study is needed.

Other known threats to boojum include urban sprawl, expansions of agricultural frontiers, climate change, and harvesting for ornamental wood.

The El Vizcaíno Biosphere Region was created in 1988. This protected area is 9,625 sq. miles and is the largest protected wildlife refuge in Mexico. It is home to some boojum, as well as many other protected species. The El Vizcaíno Biosphere Region borders on the Valle de los Cirios.

The Valle de los Cirios, located near Guerrero Negro on the Baja California Peninsula, is the second-largest wildlife protection area in Mexico. This area was deemed a nationally-protected area in 1980 and encompasses over 9,500 sq. miles. The Valle de los Cirios contains a large population of boojum and is home to the highly endangered Desert Pronghorn. It is listed as a tentative site to become a World Heritage Site.

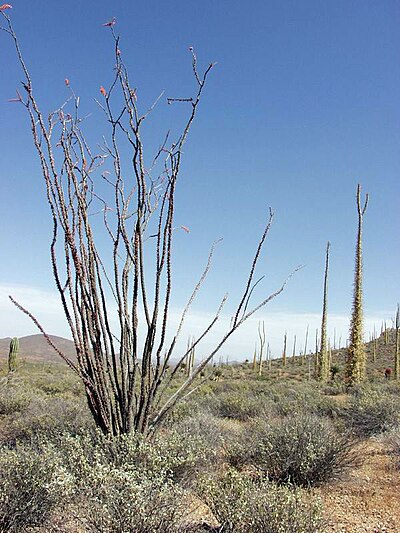

Fouquieria Splendens

[edit | edit source]This unique plant named the Ocotillo also known as a Fouquieria Splendens is a tall, greyish/greenish spiky plant from the Plantae family. This plant isn't considered a true cactus even though it is covered in thorns and is ingenious to both the Sonoran Desert and the Chihuahuan Desert.

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]The Ocotillo does flower but only when it rains and when the flower dries it can be collected and used for tisanes which is an herbal tea. Also, Native American use to use to cut off the flowers when they blossomed and also cut of parts of the root and collect them for when someone in the tribe use to get cut they would apply either the root or the flower on the open cut which slowed down the bleeding.

Ecological Significance

[edit | edit source]Both White-Tailed deer and Mule deer have the Ocotillo in their diet, but white-tail deer tends to eat much more Ocotillo than the Mule deer. Because the Ocotillo does flower both hummingbirds and native carpenter bees are able to get nectar from them which also helps the Ocotillo spread its pollen. Also, it can provide some cover or shelter from the hot desert for smaller mammals, birds and reptiles.

Agave shawii

[edit | edit source]This plant is also known as Shaw's agave or coastal agave. These plants which are part of the genus agave are drought resistant which makes them great for living in the desert. Their roots respond fast to rain which is a good adaptation for life in the desert. These plants were used by Kumeyaay Native Americans as a source of food, tools, and even clothing. They would make many things by beating the leaves which would result in fibers that they would use for rope, clothing, traps, sandals and many other things.

Climate & Geology

[edit | edit source]Water & Land Use

[edit | edit source]Opportunities & Threats

[edit | edit source]Opportunities & Threats

[edit | edit source]Climate Change

[edit | edit source]Climate change looms as the largest ecological threat to the Baja California subregion and the entire Sonoran Desert. Unchecked, the effects of climate change in the Sonoran Desert will be far-reaching and widespread throughout all biomes and ecosystems. The Sonoran Desert already finds itself in a drought with at least a 25 to 40% drop in precipitation over the last 50 years. The region has been identified as being within a projected “global hot spot” resulting from climate change, with models demonstrating warming of 5.4-10.8 degrees Fahrenheit.

Increased temperatures place strains on entire ecosystems by undermining food webs. Warming temperatures, among many other factors, will increase evapotranspiration rates, stressing primary producers and the resulting food webs. Slow-moving species such as desert tortoises will have much harder times reacting to the unpredictable weather patterns produced by climate change. Furthermore, species capable of more rapid reaction and migration may attempt to move out of designated protected wildlife areas, such as the Valle de los Cirios area, only to have their movement blocked by human habitat fragmentation.

Opportunities to address climate change exist at every moment of every person’s day on a global scale. From choosing a profession that champions global climate change causes or conducts research to a persons simple daily choices, there is a way for everyone to get involved. A plethora of information is widely available on making more sustainable choices. Other ways to help address climate change are to research and donate to the most effective organizations battling climate change. Practicing responsible civics by researching and voting for environmentally friendly legislation and candidates and starting grassroots environmental movements or joining current movements are all ways of addressing climate change.

Invasive Species

[edit | edit source]Sahara mustard weed, a large, hardy fast-growing winter annual, along with a with similar invasive grass, Buffelgrass, threaten many of the endemic flora of Baja California and the Sonoran Desert. Sahara mustard started as a localized population before beginning a massive range expansion. The weed is particularly effective at challenging native cacti and perennial shrubs for resources such as light and soil moisture. Furthermore, the weed possesses the capacity to smother native herbaceous plants.

First recorded in California’s Coachella Valley in 1927, by the 1970s the plant was widespread across the Sonoran Desert and Baja California. Sahara mustard mainly kept to disturbed soil and sandy areas until in the 1990s, when it began invading undisturbed desert. In the twenty-first century, the weed again adapted and began invading the steep desert slopes and rocky soils of the Sonoran. It is now known to cause acres of impenetrable thickets in some places, completely excluding any other annuals.

Currently, research is being conducted on the best ways to combat aggressive invasive species such as Sahara mustard weed. The most effective method to date is hand weeding. Though this method is not considered a tenable long-term solution, it has been shown to be useful while research is being developed. The Bureau of Land Management conducts hand weedings, in which they may be looking for local volunteers. Contacting your local BLM office may be one of the best ways to help fight such invasive species.

Endangered Species

[edit | edit source]Antilocapra americana peninsularis, also known as the Baja California pronghorn, is a subspecies of pronghorn endemic to the Baja California Peninsula. Antilocapra americana peninsularis is a critically endangered subspecies according to the IUCN with only an estimated 200 animals remaining in the wild.

Combatting climate change may be one of the best ways to help save the pronghorn. High mortality rates, especially during droughts have contributed to the decline of this species. Currently CONANP (Mexico’s National Commission of Protected Natural Areas) is working with American organizations such as the L.A. Zoo to stabilize the pronghorn through the Peninsular Pronghorn Recovery Program in the El Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve. Consider donating to or contacting these organizations to ask how you can help these animals. Finally, people can raise awareness about antilocapra americana peninsularis.

Like many other threats in the world, humans have a big part in this. One big issue in the Baja Californina/Gulf of California area is the vaquita. This small porpoise is threatened by gill-nets that are used to fish another endangered species the totoaba. Gill-nets are nets that are nets that are placed in the water and catch anything that tries to swim through. This is the only place that the vaquita lives in and having these nets makes them face some challenges. Although, regulations on the use of gill-nets have been established, there is still people that illegally use these gill-nets to fish and vaquitas are accidentally being caught an most of them die. They are the most endangered marine mammal of the world with less than 30 in the entire planet and none in captivity. Luckily for the vaquita there is a lot of people that are trying to help. Other than banning gill-net fishing, the Mexican government also tried to help fishers use alternatives to gill-nets so that they still have a way to make a living. Other conservation groups are also trying to remove the gill-nets but there is a lot and they keep getting replaced. Some ways that can help the vaquita is enforcing the ban of gill-nets, educating people about the vaquita and people can ask how the fish you are about to buy was fished.

Habitat Fragmentation

[edit | edit source]Many opportunities are found in Baja California because it is in the middle of both the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California. Because of this tourism is in every city that is in the shore to either of the Pacific Ocean or the Gulf of California. For example, San Felipe is in the shore of the Gulf of California and because of this many people from both the U.S and other parts of Mexico go there to enjoy the beach. Also because of the tourism the beaches bring San Felipe they also host an off-road racing event named San Felipe 250 which happens yearly bringing more people to this city.

The threats from what the Baja California Peninsula and the Gulf of California suffers from are all done by humans. The principal threats are livestock ranching, salt extraction, and hunting. With ranching many acres of space are taken away in which affected both populations of mule deer and bighorn sheep significantly. With hunting because so much deer type animals are being hunted it has affected the population of Pumas in the area due to they no longer have their main source of food available as much as they were having. And with the salt extraction from the see this has negatively affected the breeding and migration of gray whales.