User:Cinndeee

Biodiversity

[edit | edit source]Coyote

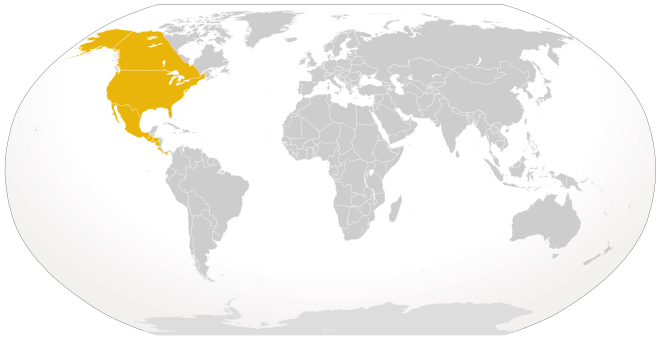

[edit | edit source]The Coyote (Canis latrans) is a canine that lives in North America, roaming the plains, deserts, mountains, and forests (Bradford, 2017). Coyotes are primarily carnivorous, they prey on rabbits, birds, deer, reptiles, fish, invertebrates, and amphibians. Occasionally, they eat fruits and vegetables. Humans are considered to be the biggest threat to coyotes, followed by gray wolves and cougars. The average coyote weighs about 20 to 50 pounds (Bradford, 2017) . The hair of this animal varies depending on where they are geographically located, determining whether the color is grey, white, tan, or brown (Bradford, 2017).

Habitat

[edit | edit source]Coyotes live in North America where they roam the mountains, plains, forests, and deserts of the United States, Mexico, and Canada (Bradford, 2017). Although coyotes are known to easily adapt to different habitats, they typically prefer to live in open areas like deserts and prairies. As humans take more and more land, coyotes can also be found living around large cities, where they are beginning to adapt.

Diet

[edit | edit source]Although they are thought to be only meat eaters, coyotes are actually omnivores--eating vegetation and meat (Bradford, 2017). Generally, coyotes are scavengers and are predators of small prey, but occasionally, they shift to large prey. Coyotes will prey on birds, rabbits, reptiles, fish, deer, invertebrates, and amphibians (Bradford, 2017). Some fruits and grains they feed on include, berries, apples, peaches, watermelon, carrots, beans, wheat, and corn. Most of the time coyotes hunt alone, but when hunting for large prey such as deer, they will hunt in packs (Bradford, 2017). For those that live in large cities, coyotes will normally kill pets and livestock, eat pet food, or garbage(Bradford, 2017).

Life Span

[edit | edit source]The average lifespan of a coyote is six to eight years in the wild, while those in captivity can live twice as long ranging from thirteen to fifteen years (General Information About Coyotes, n.d.). They are affected by a variety of diseases and parasites which include, intestinal worms, heartworms, fleas, and ticks (Disease, 2020). They may also be affected by parvovirus, canine distemper, and mange (Disease, 2020). However, humans are considered to be the greatest threat to humans. In rural areas, the major cause of death is due to trapping and hunting, while in urban areas, the cause of death is primarily automobiles (General Information About Coyotes, n.d.). There has been an average of automobile collisions from 40 to 70 percent each year (General Information About Coyotes, n.d.).

- REDIRECT [[1]]

Importance

[edit | edit source]Coyotes play an important ecological role in the environment by helping maintain healthy ecosystems and boosting biodiveristy. As they are the top carnivores in some ecosystems, they regulate mesocarnivore populations, which include, foxes, skunks, opossums, and raccoons.

Facts

[edit | edit source]- Coyotes can run up to 40 miles an hour.

- Coyote pups are born blind.

- Coyotes are nocturnal.

- Coyotes are monogamous and only have one mate for the rest of their life.

- Coyotes have few natural predators. They include mountain lions, wolves, and bears.

Derived from Coyote Information, Facts, and Photos, 2015.

Fish-hook Barrel Cactus

[edit | edit source]The Fish-hook Barrel Cactus (Ferocactus wisilizeni) also called the Arizona barrel cactus is a species of flowering plant in the cactus family Cactaceae (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.). The fish-hook cactus is characterized by its two-foot diameter, long hooked spines, and barrel body shape (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.). On the cactus, yellow/red flowers and yellow fruit grow at the superior surface. This species of barrel cactus can be found in Northern Sonoran, Mexico and in South-Central Arizona (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.). The fish-hook barrel cactus has a life span of about 50-100 years (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.). The conservation status of this plant is vulnerable and the population is decreasing.

Habitat

[edit | edit source]The fishhook barrel cactus is found throughout South-Central Arizona and Northern Sonoran, Mexico (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.). It grows primarily in gravely slopes and desert shrubs, but it can also grow in deserts often on rocky, gritty, or sandy soils on the hillsides from 1,000 to 4,600 feet elevation (Barrel Cactus, n.d.). The fishhook barrel cactus does not need much water to survive as it can tolerate dry soil moisture, but it does require lots of sunlight. This heat-tolerant plant contains "fishhook" spines along the cactus body to protect it from herbivores. At the top of the cactus, the plant grows yellow/red flowers and yellow/red fruit (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.).

Importance

[edit | edit source]The fishhook barrel cactus is important not only because it enhances the beauty of the desert landscape, but it provides fruit to animals and birds. Javelina, birds, and deer eat the fruit; the birds especially like the seeds. The fruit can also be used to make candies and jellies.

Facts

[edit | edit source]- The fishhook barrel cactus is often called the "Compass Barrel" because most of the larger plants lean towards the southwest (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.).

- The cactus does contain water, but if it is ingested it can cause diarrhea due to the oxalic acid it contains (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.).

- The lifespan is 50-100 years (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.).

- It commonly grows 2-4 feet tall but can grow up to 6-10 feet tall in some cases (Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet, n.d.).

Geology and Climate in the AZ Uplands and Sonoran Plains

[edit | edit source]Tectonic Plates

[edit | edit source]The slow continental drifting of landmasses are called tectonic plates (or lithospheric plates) and they drift across the lines of latitude and longitude (Plate Tectonics, 2020). The tectonic plates have been moving since the beginning of time (Plate Tectonics, 2020). Movement of the tectonic plates affects the oceanic and atmospheric circulation, climate, storm tracks, and the duration and timing of seasons (Phillips et al, 2015, p. 71). Each year, the tectonic plates move slowly across the Earth by several inches (Phillips et al, 2015, p. 71). When the continents collide, one plate will usually be forced underneath the other plate, which will result in the upthrust of mountain chains (Phillips et al, 2015, p. 71). Movements of these faults can turn a flat plain into a massive mountain range. As the mountains take form, biomes begin to develop along their slopes.

Mountains

[edit | edit source]Tucson Mountains

[edit | edit source]Located west of Tucson, Arizona, the Tucson Mountains is not impressively high as they only reach up to 4,687 feet (Tucson Mountains Tucson AZ, n.d.). They may be short in stature, but they are big in beauty. The Tucson Mountains are the remains of a collapsed volcano ranging 15 miles long (Tucson Mountains Tucson AZ, n.d.). Towering stratovolcanoes erupted here ejecting hot volcanic debris about 70 million years ago (Tucson Mountains Tucson AZ, n.d.). The Tucson Mountains were pulled westward for miles across the detachment fault to where they are today (Phillips et al, 2015, p. 77). As I stated before, the Tucson mountains were once a volcano located on the western side of the Santa Catalina Mountain (Phillips et al, 2015, p. 77). For 20 miles, the top of the volcano slid to the west and formed a valley between the Tucson and Santa Catalina Mountains (Phillips et al, 2015, p. 77). The occurrence of detachment faulting was discovered by scientists from the University of Arizona in the Santa Catalinas (Phillips et al, 2015, p. 77). The Tucson Mountains are composed of an extrusive ingenious rock created by the eruption of the volcano called rhyolite.

Santa Catalina Mountains

[edit | edit source]

About 70 million years ago, a massive volcano formed where the Santa Catalina Mountains are today (Geocoaching, 2013). The volcano then created a circular basin called a caldera after it collapsed on itself (Geocoaching, 2013). Then 40 million years later, detachment faults caused the upper part of the caldera to slide 20 miles off the lower region due to detachment faults (Geocoaching, 2013). The creation of the faults produced mountain ranges and valleys. This caused Tucson to drop 3,300 meters down, creating the valley that has since been filled with 1,650 meters of sediment (Geocoaching, 2013). The upper caldera became the Tucson Mountains, while the lower caldera and underlying granite that was left higher on the north side of the valley became the Rincon Mountains and Santa Catalina Mountains (Geocoaching, 2013).

The Santa Catalina Mountain lies north and northeast of Tucson, Arizona. It is often referred to as Catalina Mountain or Catalinas (Santa Catalina Mountains, 2020). The highest point in Catalina Mountain is Mount Lemmon with an elevation of over 9,157 feet above the sea level (Santa Catalina Mountains, n.d.). Annually, this region receives about 180 inches of snow (Santa Catalina Mountains, 2020). The Catalina is the most prominent of the other five regions(Santa Catalina Mountains, n.d.). One of the most popular activities on this mountain is hiking. The Santa Catalina Mountain is composed of an intrusive ingenious rock formed from the solidified magma below the volcano called granite (Santa Catalina Mountains, 2020).

Rincon Mountains

[edit | edit source]

The Rincon Mountains is one of the five mountains surrounding the Tucson valley located on the east of Tucson, Arizona. he Rincon Mountain is one of the many ranges that belong to the Basin and Range Province. The basins in the Basin and Range Province are from the result of block faulting that occurred 10-25 years ago (Geology of the Rincon Mountains, n.d.). They are separated by the basin filled with thousands of feet of alluvial sediment that are derived from erosion of the mountains (Geology of the Rincon Mountains, n.d.). The Rincon Mountain is highly eroded with metaphoric core complex--a mass of bedrock (Geology of the Rincon Mountains, n.d.).

The mountain is steep and rugged with many rocky ridges and deep canyons to explore. It is composed of a highly eroded mass of bedrock known as a metaphoric core complex (Geology of the Rincon Mountain, n.d.). The Rincon Mountains' highest peaks include the Mica Mountain with an elevation of 8,664 feet and Rincon Peak at 8,482 feet (U.S. Forest Service, n.d.). The Mica Mountain's high elevation supports the spruce vegetation and Ponderosa Pine, while lower elevations have oak-pine forests (U.S. Forest Service, n.d.). Some special places to explore in this mountain include Rincon Mountains Wilderness and the Saguaro National Park, Rincon Mountain District (U.S. Forest Service, n.d.). Rincon Mountains also provides many hiking trails to explore including Douglas Spring Trail, Rincon Peak, Cactus Forest Trail, etc.

Santa Rita Mountains

[edit | edit source]

The Santa Rita Mountains lie south of the Tucson Basin. It has the highest point in the Tucson area with the highest peak at Mount Wrightson with an elevation of 9,453 feet (Santa Rita Mountains, 2020). Within the range is Madera Canyon that is used as a resting area for migrating birds and is a premier bird-watching area. Santa Rita Mountains is also home to "El Jefe," an adult male jaguar that was first identified in 2011 (Santa Rita Mountain, 2020). Santa Rita Mountain also contains trails like the Bog Springs Trail, Cave Creek, and Old Baldy Trail.

Tortolita Mountains

[edit | edit source]The Tortolita Mountains are located northwest of Tucson, Arizona. Its highest peak elevation is 4,696 feet (Tortolita Mountains, 2020). Established in 1986 by Pima County, the Tortolita Mountain Park protects most of the mountain range (Tortolita Mountains, 2020).

Land and Water Use

[edit | edit source]Arizona Uplands Land Use

[edit | edit source]Saguaro National Park

[edit | edit source]

Tucson, Arizona is home to the largest cacti in the nation. The Saguaro Cactus is the universal symbol of the American West that provides nesting areas, shelter, and food for many animals (VandenBerg, 2018). The Saguaro National Park, located in Southern Arizona, protects the native species and wildlife of the Sonoran Desert. It has two locations on both sides of the city of Tucson located East and West with a total of 91,327 acres (Saguaro National Park). The eastern section of the Saguaro National Park is larger, contains many mountains, rises over 8,000 feet, and has 128 miles of hiking trails (Saguaro National Park). The western portion has a denser saguaro forest and is lower in elevation (Saguaro National Park).

The Saguaro National Monument was created in 1933 (Saguaro National Park). Then in 1975, 71,400 acres of the Saguaro Wilderness area was added (Saguaro National Park). The Saguaro National Park was not established until October 14, 1994 (Saguaro National Park). It has provided many activities to thousands of visitors which include watching the breathtaking Arizona sunsets, hiking, picnics, and embracing the cactus diversity. However, there are any threats that affect this park, this includes invasive plants, fires, theft, and vandalism. The Saguaro Cactus is protected under the Native Plant Protection Act (VandenBerg, 2018). If an individual is caught cutting down a saguaro, they may be charged with felony criminal damage that can result in 25 years in prison (VandenBerg, 2018). Other actions of vandalism that include transplanting the cactus and theft will result in high fees and jail time (VandenBerg, 2018).

Las Ciénegas National Conservation Area

[edit | edit source]

Las Ciénegas National Conservation Area in Southeastern Arizona protects more than 45,000 acres of rolling grasslands and woodlands (Las Ciénegas NCA, 2014). The oak-studded hills in the region connect several lush riparian corridors and "sky island" mountain ranges (Las Ciénegas NCA, 2014). Within the Las Ciéngas National Conservation Area flows the Ciénega Creek that supports the diverse plant and animal community and is rich in cultural and historic resources (Las Ciénegas NCA, 2014). The Empire and Ciénega ranches are now managed by the Bureau of Land Management under the principals of ecosystem-management and multiple uses for future generations to enjoy (Las Ciénegas NCA, 2014). The Bureau of Land Management has formed a partnership with Empire Ranch Formation, a non-profit organization, which is dedicated to preserving the landscapes and historic buildings (Las Ciénegas NCA, 2014). There are many activities for visitors to do, which include birdwatching, wildlife viewing, picnicking, hunting, horseback riding, hiking, mountain biking, primitive camping, visiting historic sites, photography, and scenic drives (Las Ciénegas NCA, 2014).

Los Morteros Conservation Area

[edit | edit source]Los Morteros is located south of the Town of Marana's El Rio Open Space Preserve. It's 120 acres of land embodies major traditions of the region that include Mexican, Spanish, Native American, and the American Territorial (Los Morteros, 2020). It is a site that was once inhabited by a large NativeAmerican village between about A.D. 850 and 1300 (Los Morteros, 2020). It was once a large village that stretched North and South along the Santa Cruz River and Past Silver Road (Los Morteros, 2020). The site was named "Los Morteros" by archaeologists because they discovered many many bedrock mortars on the site (Los Morteros, 2020). Los Morteros is a site where many important events took place in Southern Arizona. The undisturbed buried remains make Los Morteros an important cultural resource because they provide a lot of information about the history of the Tucson Basin (Los Morteros, 2020). In fact, Tohono O'odham Nation considers this place as an ancestral site (Los Morteros, 2020). The Pima County Conservation Area protects the archaeological and historic resources to preserve them for the future of Pima County (Los Morteros, 2020).

Agriculture

[edit | edit source]

There are many agricultural areas in Tucson in which they cultivate the soil, grow crops, and raise livestock. The plant and animal products are prepared for people to use and distribute into markets. The crops grown in Tucson include corn, cotton, wheat, pecans, vegetables, alfalfa, barley, citrus, and hay (Water and Irrigated Agriculture in Arizona, 2018).

Civilization

[edit | edit source]Tucson is a large city that lies in Arizona Uplands of the Sonoran Desert. It is home to a large population of 545,975 (Tucson, Arizona, 2020). Land use in this area is used for recreational, transport, agricultural, residential, and commercial purposes. The land in the AZ Uplands is used to make houses, malls, stores, airports, roads, etc. As the population continues to grow by the minute, more and more land will be taken from the desert. Humans are the biggest threat to the wildlife that lives in the AZ Uplands.

Plains of Sonora Land Use

[edit | edit source]Residential Land Use

[edit | edit source]Hermosillo is the capital of a large city that is centrally located in the Northwestern Mexican State of Sonora (Hermosillo, 2020). It has a population of over 812,229 inhabitants (Hermosillo, 2020). It is the 16th largest state in Mexico (Hermosillo, 2020). As the population continues to increase, more land will be taken to accommodate the growing population. The majority of land around the Plains of Sonora has been taken over by humans for residential, agricultural, transport, recreational, and commercial purposes.

Agricultural Land Use

[edit | edit source]

Hermosillo uses some of their lands for agriculture, growing crops that include grapes, wheat, flowers, alfalfa, walnuts, and chickpeas (Hermosillo, 2020). Rico Farm in Hermosillo, Mexico at Campo San Luis grows vegetables and has row crops that include tomatoes, melons, cucumbers, eggplants, and squash that are primarily grown for transport (Hermosillo Rico Farm, 2017). This farm manages approximately 4,000 acres of land and most of the area is left in a natural state (Hermosillo Rico Farm, 2017). Livestock is also important in this Hermosillo. There are many farms that raise cattle, sheep, pigs, horses, goats, and even bees (Hermosillo, 2020).

Commercial Land Use

[edit | edit source]Industry and manufacturing is the dynamic sector of the economy in Hermosillo (Hermosillo, 2020). Thirty percent of the population is employed by 26 major manufacturers in Hermosillo (Hermosillo, 2020). Products manufactured in Hermosillo include cars, computers, televisions, textiles, wood products, cellular phones, printing, food processing, chemicals, and more (Hermosillo, 2020). Commerce employs more than half of the population (Hermosillo, 2020). Therefore, the majority of the land is used for commercial purposes.

References

[edit | edit source]- Barrel Cactus. (n.d.). Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.desertusa.com/cactus/barrel-cactus.html

- Bradford, A. (2017, September 26). Coyote Facts. Retrieved from http://www.livescience.com/27976-coyotes.html

- Coyote Information, Facts, and Photos. (2015). Retrieved from https://forum.americanexpedition.us/coyote-facts-information-and-photos

- Disease. (2020). Retrieved from https://urbancoyoteresearch.com/coyote-info/disease

- Fishhook Barrel Cactus Fact Sheet. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.desertmuseum.org/kids/oz/long-fact-sheets/Fishook Barrel Cactus.php

- General Information About Coyotes. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://urbancoyoteresearch.com/coyote-info/general-information-about-coyotes

- Geocaching. (2013, December 24). Tucson Mountains. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.geocaching.com/geocache/GC4X199_tucson-mountains?guid=a8079cbe-9156-4af1-a299-464a3c368b0b

- Geology of the Rincon Mountains (n.d.) Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/sagu/planyourvisit/upload/Geology%20of%20the%20Rincon%20Mountains.pdf

- Hermosillo. (2020, March 25). Retrieved from Hermosillo

- Hermosillo Rico Farm. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.bridgesproduce.com/hermosillo

- Las Cienegas NCA. (2014, February 21). Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20140623053135/http://www.blm.gov/az/st/en/prog/blm_special_areas/ncarea/lascienegas.html

- Los Morteros. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/explore/los-morteros/

- Phillips, S. J., Comus, P. W., & Dimmitt, M. A. (2015). A natural history of the Sonoran Desert (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Plate Tectonics. (2020, April 30). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plate_tectonics

- Saguaro National Park. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.saguaronationalpark.com/

- Santa Catalina Mountains. (n.d.). Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/recarea/coronado/recreation/recarea/?recid=25602&actid=29

- Santa Catalina Mountains. (2020, April 27). Retrieved from Santa Catalina Mountains

- Santa Rita Mountains. (2020, April 27). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santa_Rita_Mountains

- Tortolita Mountains. (2020, March 12). Retrieved from Tortolita Mountains

- Tucson, Arizona. (2020, April 27). Retrieved from Tucson, Arizona

- Tucson Mountains Tucson AZ. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.premiertucsonhomes.com/tucson-mountains-tucson-az/

- U.S. Forest Service. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/beauty/Sky_Islands/Coronado_NF/RinconMountains/index.shtml

- VandenBerg, K. (2018, August 28). Laws Protecting Saguaro Cactuses. Retrieved from https://hikephoenix.net/2018/08/28/laws-protecting-saguaro-cactuses/

- Water and Irrigated Agriculture in Arizona. (2018, June 27). Retrieved from https://wrrc.arizona.edu/sites/wrrc.arizona.edu/files/attachment/Arroyo-2018-revised.pdf