Transportation Systems Casebook/Governance of street space and best practices

Summary

[edit | edit source]This Case Study provides a glimpse of Arlington County's street governance practices. The study looks at streets from three perspectives (below-grade, at-grade, and above-grade) to gain a full impression of the regulation, planning, design, and construction of the street space. As a county that lacks municipal governments, instead relying on its County Board to govern, Arlington County's governance and planning provide examples of best practices based on a variety of factors, but most specifically, based on its citizenry. Local government emphasizes the importance of citizen input to optimize resources and address issues throughout the entire county, often serving in voluntary committees tasked with setting long range plans. Additionally, Arlington County envisions and regulates streets as places that should be equally amenable to all forms of transportation, from walking to biking, driving to public transit, able-bodied and disabled, a vision that they call Complete Streets.

Case Study Selection: Arlington County

[edit | edit source]

Arlington County provides an excellent case study of Street Governance. The County has both a strong commitment to including its citizens in the transportation planning process and a strategic vision of providing an interconnected system of "Complete Streets" that allows local members of the community various affordable transportation options.

Commitment to Public Involvement

[edit | edit source]Arlington County actively engages local citizens to participate in the transportation planning process. The Arlington County website provides opportunities for members of the public to report transportation-related issues, provide feedback on transportation and transit facilities, and utilize online tools to plan trips given existing facilities. Specifically, citizens can report a pothole, a street light outage, a broken or missing traffic sign, or a sidewalk problem. Additionally, citizens may submit requests for new sidewalks, handicap ramps, or new pavement markings.[1] This type of interactive planning is helpful to Arlington County staff because they can use this crowd-sourced information to identify critical areas, or hotspots, where transportation-related improvements are most needed. Additionally, it helps citizens by providing a direct means for feedback, so they know that their concerns are considered by county staff.

Further, the “Arlington Way” is a methodology for gathering citizen input through Citizen Advisory Groups. These groups interact with county staff, the County Board, public officials, civic associations/organizations/groups, and residents in the county. Citizen Advisory Groups vary based on the development or community changes suggested. The main goal of these Groups is to identify the development option that generates the most overall community support. Therefore, the purpose of the “Arlington Way” is to ensure that all stakeholders in a development of community have the ability to provide comment and input.[2] Consistent with this engagement is the provision of information to the public through a multitude of county-run websites and social media outlets, managed explicitly by the county's social media policy and overseen by the County Manager's office.[3][4] Consistent with these rules for public information, the county has published a set of "Key Performance Measures" online, among them "Performance Measures for Mobility", by which the public may measure how effective the county is in governing.[5] Additionally, the details of all projects and plans, including strategic visions for future transportation demands, are publicly available in near real-time through the county's website.[6] Arlington County’s commitment to this all-inclusive community engagement forum is unique and laudable, as it ensures all citizens have a voice in the transportation planning process.

Vision of Complete Streets

[edit | edit source]

Arlington County has a Complete Streets program intended to support local projects that "improve safety and access for pedestrians, transit riders and bikers on noncommercial arterial streets, as well as improve street aesthetics, stormwater management and bioretention."[7] The County also supports the Neighborhood Complete Streets Committee (NCSC) that assists in identifying these improvements in coordination with the county's Master Transportation Plan and individual neighborhood needs.[8] A planning staff member from Arlington County noted that the agency took interest in the concept of complete streets in the early stages of its popularity. Arlington County focuses on multi-modalism: planning facilities that can work for everyone.[9]

Arlington's progress toward achieving this Complete Streets vision is evident in its national walkability and bikability rankings. Arlington County received Gold-Level recognition from the organization Walk Friendly Communities, a group sponsored by the US Federal Highway Administration and FedEx.[10] Arlington also received a Silver-Level rating from the Bicycle Friendly Community program, sponsored by the League of American bicyclists.[11] Additionally, Arlington offers a wide variety of public transit options including the Arlington Transit (ART) bus system, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) Metrobus system, the WMATA Metrorail system, and Virginia Railway Express (VRE) heavy rail system, which encourages the concept of complete streets by encouraging non-single occupancy vehicle transportation.[12]

Arlington County Staff acknowledged that its ability to integrate complete streets concepts onto County roads relates directly to the County's Transportation Demand Management (TDM) strategies.[9][13][14] By working with the public (residents, businesses, employees, etc.) to identify the best strategies and policies to get commuters and travelers out of their cars and on to alternatives, Arlington County creates a solid framework for the use of complete streets infrastructure. Encouraging alternatives to driving helps make the County's transportation system work better because there are fewer cars on the road.[9]

Methodology

[edit | edit source]To gain a comprehensive understanding of Street Governance in Arlington County, this research included assessment of Arlington County codes[15] and general transportation planning strategies. To better understand how these regulations relate to the overall planning process, the research team conducted interviews with Arlington County government managers and planning staff.[9][13][14]

The research team divided Street Governance into three areas of consideration:

- Below-Grade: Codes and planning strategies related to underground street utilities and infrastructure.

- At-Grade: Codes and planning strategies related to surface street space including parking, bike lanes, pavement, sidewalks, traffic calming, etc.

- Above-Grade: Codes and planning strategies related to above-ground street facilities including signage, signalization, overhead utilities, lighting, etc.

The discussion of best practices will consider each of these three areas of consideration.

Timeline

[edit | edit source]

| From the Arlington Historical Society:[16] | |

| 1722 | Iroquois cede to colonial Virginia the lands encompassing present-day Arlington County |

| 1720s onward | Settlement of Falls Church and Alexandria |

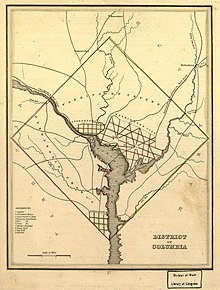

| 1791 | U.S. government assigns lands to the District of Columbia, including present-day Arlington County |

| 1797 | First bridge across the Potomac River; opening of Leesburg Turnpike |

| 1801 | Creation of Alexandria County |

| 1808 | Opening of Chain Bridge across the Potomac River |

| 1833-1843 | Construction of the Alexandria Canal to link to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal |

| 1847 | County of Alexandria ceded from District of Columbia to Virginia, in part to assist funding of the Alexandria Canal |

| 1870 | Town of Alexandria became an independent city, separate from present-day Arlington County |

| 1920 | Alexandria County renamed Arlington County |

| 1932 | County and municipal governments combined as a County Board under Code of Virginia (first County Manager in the United States) |

| 1940s | Arlington expanded existing trolley lines to support rapid increase in wartime and postwar military and civilian workers and families |

| 1950 | First county-wide planning process for capital improvements in public infrastructure |

| 1957 | Creation of the "Code of the County of Arlington, Virginia"[15] |

| 1959 | County Board issued fiscal and capital improvement projections |

| 1960s | Development of County master plan for development; birth of the "Arlington Way" |

| From other sources: | |

| 2012 | Formalization of the Arlington Way as PLACE[17] |

| 2013 | Transition of all at-grade and below-grade commercial project planning to an online electronic system[14][18] |

| 2016 | Projected expansion of electronic plans review process to residential projects[14] |

Maps

[edit | edit source]Google Map of Arlington County

Arlington County uses online resources to inform citizens of street-level activity and infrastructure. The following maps are available on the websites of Arlington County's affiliate organizations:

Arlington County Bike Map published by Bike Arlington to show where bike lanes exist throughout the County.

Arlington County Bike Comfort Level Map published by Bike Arlington to illustrate the skill-level of each bike lane in the County.

Arlington County Traffic Camera Interactive Map live-streamed by Arlington County at specific traffic camera locations throughout the County to help drivers identify traffic issues before driving.

Arlington County Interactive Transit Map published by Arlington County to help transit-users easily identify apporpriate bus routes and transfer locations to plan their trips.

Arlington County Bikeshare Transit Development Plan Map Set published by Bike Arlington to not only show bikeshare locations, but also provide a picture of Arlington County's bikeshare and demographic trends.

Red Light Camera Locations in 2010 published by Arlington County points out four intersections with red light cameras.

Red Light Camera Locations in 2015 published by Arlington County points out five intersections with red light cameras.

Actors

[edit | edit source]The following stakeholders are involved in the development, maintenance, and regulatory oversight of the streets and roads in Arlington County.

Local Government

[edit | edit source]The county government offices listed here provide direct governance of the streets in Arlington County. They are responsible for implementing and enforcing all federal, state, and county laws, regulations, and codes. Other county agencies may play supporting roles in governance as needed.

- Arlington County Board: Includes five members who serve Arlington County through legislative jurisdiction; transportation policy development and decision-making; land use/zoning development and decision-making; taxation policy development and implementation; nominations for advisory committees; acknowledgement/response to community complaints; and other policy-related tasks.[19]

- County Manager's Office: Involved in general operations and services.

- Department of Community Planning, Housing & Development: Involved in zoning and strategic planning.

- Department of Environmental Services: Involved with streams, stormwater, ecology-realted matters, and energy-related matters.

- Division of Facilities and Engineering - formerly "Public Works": Involved with public utilities and above-grade development.

- Division of Transportation: Involved in right of way development and coordination of environmental policy compliance with the State Department of Transportation and federal agencies.

- Department of Parks & Recreation: Works in "green space" development and maintenance.

- Police Department: Enforces all traffic laws and misdemeanor infractions of site permits or interference with county agency site inspections.

- County Manager's Office: Involved in general operations and services.

- Judiciary: The legal bodies that concern both enforcement and regulation of transportation policies.

- Circuit Court – 17th Judicial Circuit: Involved in judicial hearings for damages

- General District Court: Involved in misdemeanor cases; preliminary hearings for possible felonies; claims for damages not greater than $25,000; and processes records such as criminal warrants, civil cases, and traffic summonses.

Private Entities

[edit | edit source]Although not directly responsible for governance, due to Arlington County's investment in civic engagement, the following private parties help shape the governance of the county's streets and roads:

- Land Developers: Companies that drive land use patterns and, thus, affect infrastructure needs in the transportation system.

- Business Owners: The type of street on which a business is located may yield an impact on the business by either attracting or deterring customers via pedestrian, bicycle, transit, auto traffic, or parking facilities. Local business owners have a strong stake in the design of their neighborhood roads. For example, a recent study by the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) found that "improved accessibility and a more welcoming street environment" increased local retail sales.[20] As one of the final phases for any project that affects the rights of way along the business fronts, county officials, project applicants, and the affected business owners meet to discuss details of the project; business owners have the opportunity to reject site plans or traffic management plans.[14] They may also submit their own plans for approval.[14]

- Property Owners: Street design also impacts property value. For example, the NYCDOT study also found that "simply improving street design can have a major impact on market values." [21]

- Private School Boards: Like business owners, private school boards also sit on plan approval meetings for projects affect the rights of way along their properties. They can submit development plans for approval.

Public Entities

[edit | edit source]Much as with private entities, the following members of the public advise and help shape the governance of the county's streets and roads:

- Members of the Public: Pedestrians, bicyclists, drivers, transit-users, and citizens affected by neighborhood streets, etc.

- Community Organizations: Groups registered with the County Board that provide input to county agencies on all rights of way development projects.

- Advisory Groups and Commissions: Approximately 50 advisory groups advise the County Board on development projects and budgets.[22]

- Condo, Homeowner & Tenant Associations and Citizen & Civic Associations: Sit on meetings with county agencies and developers during the final phases of project approvals.

- Public Interest Groups: Activists supporting specific causes related to transportation or the development of transportation infrastructure including environmentalists, non-motorized transportation advocates, ADA accessibility supporters, environmental justice advocates, and other special interst supporters.

- Public School Boards: Fulfill the same role as Private School Boards.

Policy Issues

[edit | edit source]Civic Engagement within a Commonwealth

[edit | edit source]Virginia is a commonwealth, a term that is defined popularly as a "government based on the common consent of the people."[23] Section 2 of Article I of the Constitution of Virginia, entitled "People the source of power," states "that all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people, that magistrates are their trustees and servants, and at all times amenable to them."[24] These notions form the foundation of Arlington County government's dedication to citizen engagement in all areas of government. This engagement, known colloquially to this day as the "Arlington Way," was formalized as a government initiative in 2012 as PLACE ("Participation, Leadership and Civic Engagement") and forms the bedrock of Arlington County agencies' rules for managing projects.[2][17] The PLACE initiative challenges county agencies and local communities to work together on all projects, from local ordinance creation and amendment to determining what civic improvements may occur. As noted in the most recent PLACE progress report published in 2012:

Arlington’s civic infrastructure is rooted in the belief that good ideas can come from anywhere; that collaboration among residents, businesses, civic organizations and County government typically leads to better results than any one working alone; and that strategic decisions are more likely to stand the test of time when developed through robust, creative, respectful civic conversations.[25]

PLACE represents a key management principle among the county agency managers interviewed for this article.[9][13][14] As one county manager said, "The greater good is always the rule."[13] PLACE requires community outreach for all right of way projects and stipulates that no project may proceed until the members of the community, the project designers, and the associated offices within the county government agree on the project's details.[2][17][25][14] To facilitate this, for instance, public meetings form the later stages of any building project proposal along the county's rights of way.[14][26] Prior to 2012, these meetings occurred within a less codified system that relied heavily on individual relationships among stakeholders, which, according to a 2000 report on community perceptions, sometimes led to project delays and "system chaos" among stakeholders with differing perceptions of authority and procedures.[27] Steady improvement since the 2000 report has led to the current system, which leverages social networking and collaborative online systems designed to provide concurrent, not serial, approval of development projects among stakeholders. According to one county agency manager, the online system for property site development plans review has reduced county government approval times from between 9 and 12 months down to less than 60 days.[14]

No Chartered Cities or Towns in Arlington County: Central Governance of All Streets and Roads

[edit | edit source]Arlington County uses the county board form of government defined in Chapter 4 of Title 15.2 in the Code of Virginia, meaning that none of its communities, towns, or cities are chartered ("incorporated") separately from the county government.[28] Consequently, the governance of all streets and roads resides with the county government, one of only two counties in the state which do so.[14] For state and federal roads in the county, county agencies form the primary government oversight contacts and coordinate with the appropriate state and federal authorities on behalf of county residents.[14] This consolidates all project management and funding within the county under a single set of agencies and rules. Historically, although this simplified applications for permits and oversight of projects overall, since there were only a handful of offices involved, limited staffing and information technology constraints often meant that applicants for projects would have to anticipate that county agencies could take as long as 9 to 12 months to approve plans.[14] As mentioned above, since the transition to project management using an electronic system, this time-frame has significantly decreased.[14] Although there may be residual complications with residential projects away from the town center, the research team did not identify any complaints directed at county government through popular media and a complete review of county documents through a Freedom of Information Act request was beyond the scope of this research.

Wealth, the Tools It Affords, and the Commitment It Requires

[edit | edit source]As illustrated in the table below, according to the United States Census Bureau, between 2009 and 2013 the median household income of Arlington County residents was roughly twice that of the national average and 61% higher than the statewide figure. Compared to national and statewide figures, Arlington county has a lower percentage of unemployment (by a factor of 3 to the national figure), fewer people not in the labor force, and fewer family households. Virginia's statewide figures closely match national figures.

| Arlington County | Virginia | United States | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median household income (2009-2013) | $103,208 | $63,907 | $53,046 |

| Family households as percent of population | 46.1% | 67.4% | 66.4% |

| Median family household income | $139,244 | $76,745 | $64,719 |

| Percent of population aged 25 to 54 (2013) | 56.4% | 42.3% | 40.8% |

| Percent Unemployed (2013) | 3.9% | 7.2% | 9.7% |

| Aged 16 and over, not in labor force (2013) | 20.8% | 33.3% | 35.7% |

| High school graduate or higher, percent of persons age 25+ (2009-2013) | 93.7% | 87.5% | 86.0% |

| Bachelor's degree or higher, percent of persons age 25+ (2009-2013) | 71.7% | 35.2% | 28.8% |

These figures indicate that Arlington County is wealthier and more educated than state and national averages, with fewer unemployed. In 2013, the online newspaper ArlNow reported that U.S. Census data drawn from the same source as the above table positioned Arlington County as the "richest in the nation" by family household income.[33] As noted by county officials, this wealth provides the resources to engage with the community through social media, extensive website outreach, and numerous public meetings. It also ensures adequate staffing at county agencies and allows project management agencies to host and mandate the use of an electronic computer aided design application for all site development projects.[13][14] According to the county agency managers interviewed, with these resources also comes the cultural understanding within the government that higher levels of public service are necessary, especially in the form of public outreach.[9][13][14]

Best Practices

[edit | edit source]Below-Grade

[edit | edit source]Stormwater Management and Street Drainage: Since 1992, Arlington County has implemented stringent municipal stormwater management policies consistent with the Virginia Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act of 1988[34] and U.S. federal standards under Section 402 of the Clean Water Act of 1972.[35] In 2013, Arlington County was the first county in Virginia to adopt "next generation" stormwater management practices beyond current nationwide standards, consistent with the U.S Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) "Phase III Rules" under the Clean Water Act.[14][36][37] The EPA published a case study about Arlington County entitled "Innovative Stormwater Management Standards and Mitigation," to serve as an example of municipal stormwater management practices for other municipalities attempting to implement Phases I and II of the Clean Water Act.[38] This dedication to environmental protection extends to control of stormwater runoff for all development projects along and under the County's streets. Each project of 2,500 square feet or greater must submit "a plan of development that includes a landscape conservation plan, a stormwater management plan, and an erosion and sediment control plan."[38] According to the County's Chief of the Development Services Bureau, this oversight includes the state's rights of way as well as the county's, since the state's jurisdiction for their streets that run through the county do not extend below the surface or beyond the street pavement.[14] The county enforces all issued permits through on-site inspections and roving patrols throughout the county.[14] In June 2010, the Arlington County Board set new levels of civil penalties ranging from $25 to $32,500 per day for violations of stormwater permits.[39][40] These penalties do not include associated costs to businesses or citizens incurred as a result of county inspectors issuing requirements for the immediate halt of all work when noting such violations.[14] In cases where violators do not heed the instructions of the county inspectors or obstruct the county inspectors in the course of their duties, inspectors may call for the assistance of the police.[14]

Underground Utilities: Arlington County incorporates into its county code all state and federal regulations governing the installation and maintenance of electrical services, sewage and public water, and underground residential gas distribution.[41] County websites provide user-friendly checklists for the installation, modification, or removal of services along and under county, state, and federal rights of way.[41] Plan reviewers within multiple offices concurrently review any plans and meet with permit applicants and affected residents throughout the review process.[14] County inspectors ensure compliance with all permits from the beginning to the end of any project through a mixture of site visits, formal and informal letters, and telephone calls.[13][14] Inspectors also patrol the county to confirm that unpermitted projects are not occurring.[14] The system of fines noted for stormwater management also apply here, as well as a number of penalties for any failure to comply with electrical systems requirements, fire prevention procedures, and utilities regulations.[15]

At-Grade

[edit | edit source]Pavements: Arlington County has a pavement rating system based on County-collected pavement condition data. This database is the primary method of prioritizing streets for repavement. As the County compiles this list based on the data, staff adjust the list to also consider citizen complaints or future utility work (i.e., the County will time a repavement in conjunction with water main installations, etc.). For example, Arlington County staff acknowledged the need to repave a section of Wilson Blvd. west of the Ballston area, but also recognized community interest in "road diet" strategies. Therefore, the County delayed the repavement effort to design a plan to add bike lanes and widen sidewalks during the repavement.[9]

Arlington County published official Pavement Marking Specifications in 2014. These specifications guide the marking plan, materials, dimensions, and design. Types of marking include crosswalks, cross sections, speed humps, speed tables, lane sections, bike lanes, bike/sharrow directions, bus stops, no-stopping areas, and combinations of these features. Arlington County upkeeps the pavements based on these specifications and welcomes citizen input for additional marking suggestions.[42]

Bicycle Facilities: Arlington County staff combines in-house prioritization strategies with public involvement when identifying new bicycle facilities and improvements. Arlington County's Master Transportation Plan (MTP) Bicycle Element includes a "Bikeway Facility Project List" that lists proposed bicycle improvements ranked by priority.[43] This project prioritization is not set in stone, however, as opportunities may arise that make a proposed project more or less feasible than at the time of the MTP's development. (For example, a staff member at Arlington County noted that the best time to improve or add new bicycle lanes is when the County is repaving a street space. The repavement construction process allows designers at the County to allocate the street space differently to create more right-of-way for bicycle facilities.) The County has educated and engaged staff members who monitor needed improvements based on existing conditions and crash data. In addition, as part of the Arlington Way, advisory committees combine with members of the community to identify support for specific new facilities.[9]

Arlington County introduced separated bike lanes in 2014 on Hayes Street. Separated bike lanes make bicycling safer, as they provide a barrier between the bicycle lane and car lanes, adding a layer of protection for the biker. Arlington intends to add more of these facilities, most of which will occur when coupled with repaving projects, as described above. For example, the Rosslyn Sector Plan adopted in July 2015 includes four street improvements (Fort Myer Dr. and Lynn St. will become two-way streets) that will provide space for new separated bike lanes.[44]

Traffic Calming Mechanisms: Arlington County started its Neighborhood Traffic Calming program about 15 years ago. This program originally involved residents in the community submitting their streets for evaluation for traffic calming improvements. For each submission to the program, Arlington County staff would collect speed data along the neighborhood street and assess the need for traffic calming infrastructure. In most cases, the response was the addition of speed bumps on the street. Arlington County recently "wound down" the program because staff found that the speed bumps may not be the best method of reducing local speeds.[9]

Arlington County now focuses traffic calming work on adding curb extensions. This tactic involves narrowing streets to build or expand sidewalks. Curb extensions improve visibility for both pedestrians and drivers along major arterial roadways, as curb extensions prevent parked cars from blocking pedestrian line of slight. Curb extensions also reduce the time and length of the street crossing. To implement these strategies, County staff looks at public feedback, existing conditions, and opportunities based on repavement schedules. For example, if a street is already wide, a curb extension and ADA curb ramps may be an easy, cost-effective addition during a repavement effort.

On-Street Parking: Arlington County only maintains parking spaces on the street. The County manages metered parking, as well as the residential parking permit program. To reduce excessive parking in neighborhoods nearby major destinations (shopping centers, hospitals, etc.), the County restricts parking at certain hours so only residents of that district can utilize on the on-street space. Changes in parking structure often couple with major roadway projects or repavements. The County attempts to keep as many parking spaces as possible, but also weighs the benefits of having a parking spot versus utilizing the space for a bikeshare station or other facilities.[9]

The County is also in the process of developing a Parklet program, in which former parking spaces transition into miniature park/green spaces. Parklets serve two main purposes: (1) to encourage transportation alternatives to the automobile and (2) to increase public greenspace in urban areas. The Rosslyn Business Improvement District (BID) reached out to the County during the development of the Rosslyn Sector Plan to request a parklet in a specific location. Arlington County staff investigated Virginia State Law and worked with the County Attorney to determine whether this suggestion was feasible. The County reviewed the regulations behind other areas in the state that built parklets and is in the process of finalizing the permit for the parklet was feasible for Rosslyn.[9]

|

|

Transit Infrastructure: ART (Arlington Transit) is maintained under the jurisdiction of the County. Arlington County therefore includes staff members who plan the bus stops and transit stations that contribute to Arlington's Complete Streets. Any project where there is a transit route on the street involves transit planners to review existing street space. The following bullets show some innovative techniques employed for transit integration into the streetscape:[9]

- Transit planners utilize curb extensions on commercial arterial streets for transit stops to prevent the need for the bus to pull into the curb and pull back into traffic. Using this practice, the bus can stop in the lane, allow passengers to board quickly, and continue along the route.

- Future improvements to Columbia Pike include raised curbs to meet the bus door for easy passenger boarding and alighting.

- In areas where there are high volumes of traffic, Arlington County plans to extend bus stations to two bus lengths to allow for multiple buses to load simultaneously, thus reducing dwell time.

- Arlington County prefers to locate bus stops at the far side of an intersection to allow the bus to pass through the green light and load on the opposite side of the intersection so the buses do not get caught at lights after riders board.

Above-Grade

[edit | edit source]Streetlights: In order to maintain consistency, structural/electrical integrity, and general safety, Arlington County has a detailed list of specifications required for streetlight installation. Arlington County released the most most recent set of guidelines in May 2014. These include specifications addressing contractors and developers regarding streetlight materials, electricity components, installation, inspection, design, and drawing.[45]

Arlington County requires that streetlight design begin early on in the development process to ensure proper time for review of the lighting plan. [46] For example, Arlington County requires that streetlights utilize LED lights to conserve energy through these specifications. The county also requires "light level calculations" to ensure that the amount of light shed by the infrastructure creates a safe environment for street-level activity.[47]

Traffic Signals: Arlington County also sets specifications for traffic signal requirements, construction, improvements, cabling, communication systems, materials, and design in the document released in May 2014.[45] Arlington County's specifications involve the entire traffic signalization design process from roadway work permits to fiber-optic cables, emergency signal preemption and the materials of the signal poles. By covering all of these bases in the specifications, Arlington County ensures quality and safety by design. Some exemplary work in the County Traffic Signal standards include: energy-saving LED signal materials, pedestrian buttons at each corner of an intersection, emergency vehicle preemption capability, video camera surveillance, and standard "Traffic Signal Plan Sheets" submitted to the County when a developer proposes a new traffic signal.[48]

Signage: Arlington County's Traffic Signs Program includes a variety of signs for regulation, safety, way-finding, parking, construction, and other mode-specific features for pedestrian, cyclist, and drivers. The signage program entails all public sign installation, replacement, maintenance, and removal in the County. Arlington County distinguished regulatory signs with a white backdrop and easily-legible text. Signs for safety purposes have yellow backdrops and often an image or symbol of the warning feature. Directional signs have green backdrops and often provide text that includes the location, mileage to the location, and potentially an arrow with the direction or an exit number. Signage related to the Capital Improvement Program have blue backgrounds and provide details on the project in progress. Arlington County is responsible for placing the signs based on their local knowledge of the streets. The County welcomes public involvement in the street sign program by providing both telephone and online contact information for signage suggestions.[49]

Traffic Cameras: Arlington County has a red light camera program entitled PhotoRED. The benefits of these red light cameras is twofold: they enforce prompt observance of the traffic signals and, thus, increase safety at intersections. The County’s red light cameras capture vehicles that “enter the intersection after the light has turned red for one-half of a second.” These cameras not only take three photos, but also record a short video of the violation. Intersections with PhotoRED infrastructure have signs 500-feet in advance of the intersection warning drivers about the upcoming traffic signal. Arlington County mails the violation notices to drivers and generally request a fee of $50. (Note: The infraction does not result in driver’s license points or notice of insurance.)[50]

Virginia State Code allows Arlington County to utilize camera-monitoring systems at a rate of one camera for every 10,000 residents. The current nine intersections selected for the program were recommended via Arlington County’s Traffic Accident Reduction Program due to high number of incidents and citizen complaints.[50]

The first-generation red light cameras installed in 2010 yielded a noticeable impact on each intersection, as they no longer place as high in rankings of crash location. Further, an Arlington County staff member recognized that about 97 percent of offenders do not have repeat violations. This statistic indicates that once a citizen obtains violates from a PhotoRED camera, they are unlikely to run a red light again. The staff member lauded PhotoRED for “changing the behavior of drivers,” forcing them to slow down and be more attentive while driving. The staff member also noted that the program does not rely on tax dollars, as the revenue from violators funds the infrastructure. [51]

Noise Control: Arlington County sets stringent requirements in its county code for the prevention of noise pollution.[52] These include restrictions of specific noises to "daytime," which the county defines as "the local time of day between the hours of 7:00 a.m. and 9:00 p.m. on weekdays and between the hours of 10:00 a.m. and 9:00 p.m. on a Saturday, Sunday, legal holiday."[52] Inspectors measure noise using the following criteria:

Any noise measurements made ... shall be taken from any built street at its curb or on the edge of the pavement or from any location on the property that receives the noise, unless the property that receives the noise is located in a multi-unit structure, in which case the measurements ... shall be taken from a common area within or outside the structure, or from any other unit within the respective multi-unit structure when the owner or tenant of the unit from which the measurement is to be taken consents to measurement from his, her or its unit.[52]

Among the restricted noises are construction sounds, certain levels of vehicle noise, "loud outcry" for public selling, and noise exceeding specified decibel levels. Additionally, certain noises are prohibited at whatever decibel levels, among them vehicle horns (except as emergency warning signals), loud music or video audio, and "running a commercial motor vehicle" for more than 10 minutes when the vehicle is parked or stopped (other than for traffic or maintenance).[52] The police and county officials are responsible for the enforcement of these rules; often preliminary enforcement falls to development site inspectors.[14]

Conclusions

[edit | edit source]- Arlington County's integrated and relatively safe streets are a reflection of 65 years of explicit urban development plans relying on community engagement.

- The county's commitment to multi-modal transportation options yields a system in which modes operate in harmony with one another rather than competition.

- Arlington's rules for development projects are clearly defined and publicly accessible, simplifying their implementation and enforcement.

- The ready availability of public funds is a major contributing factor to the County's ability to implement programs and infrastructure improvements.

- Citizens are a critical part of the process, in which members of the community feel connected and responsible for their streets. Further, Arlington County makes the citizen involvement process easily accessible to all through online and telephone platforms.

- Successful street governance extends beyond the actual streets. Arlington County staff acknowledged that Transportation Demand Management strategies are paramount to reducing the number of cars on the road, which ultimately makes the system more efficient.

- Automating or using computer-based systems whenever possible makes governance run more smoothly. This is apparent through the electronic development plan review program, the PhotoRED program, and the pavement database prioritization methodology.

- Arlington County's single-body jurisdiction helps to expedite processes, as there is only one governing body involved.

- County-led programs help to inspire consistent change. For example,the former Neighborhood Traffic Calming Program, the upcoming Parklet Program, the Traffic Signs Program, the PhotoRED Program, and other programs initiated by the County each work toward a single cause using a standard methodology, which makes the process easy to emulate from project to project.

- Arlington County's successful implementation of Complete Streets throughout the County underscores the importance of coupling resources. The County looks for potential improvements in every repaving project, which combines funding to achieve multiple goals.

- Standards ensure quality. Arlington County's development and publication of standards for much of its infrastructure is apparent in the quality and consistency of street features throughout the county.

Discussion Questions

[edit | edit source]- When walking, biking, or driving in Arlington County, what do you notice in terms of signage? Do you think Arlington is leading the way for other communities?

- If there was an opportunity for a Capital Bikeshare station near your house but it required the use of two on-street parking spaces, would you favor that trade-off? What about a parklet?

- Which cities do you think offer better street governance practices than Arlington? What could be done to improve local practices?

- Do you think that the level of citizen involvement in Arlington County street planning and governance is too much? Not enough?

- Are red light cameras a "fair" way to monitor driving violations?

- Does Arlington County being under one jurisdiction make it easier to implement programs and strategies?

Additional Readings

[edit | edit source]Smart Growth America's National Complete Streets Coalition: Complete Street Fundamentals

Arlington County's "Participation Leadership and Civic Engagement" program

Arlington County's list of Transportation Projects

Arlington County's Guidelines for Installing Underground Utilities Near Trees

Arlington County's Department of Environmental Services: Traffic Signal & Streetlight Specifications

Arlington County's Department of Environmental Services: Pavement Marking Specifications

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Transportation," accessed Oct 12, 2015, http://transportation.arlingtonva.us/

- ↑ a b c Abbott Bailey, "Mapping the Arlington Way: Understanding the System of Citizen Participation in Arlington County," June, 2000, http://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2014/11/Mapping-the-Arlington-Way.pdf.

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Connect with Us," accessed Oct 14, 2015, https://newsroom.arlingtonva.us/connect/

- ↑ Arlington County Manager's Office, "Administrative Regulations: Social Media Policy and Guidelines," Jun 30, 2009, http://icma.org/en/icma/knowledge_network/documents/kn/Document/6523/Arlington_County_Social_Media_Policy_and_Guidelines

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Key Performance Measures," accessed Oct 14, 2015, http://transportation.arlingtonva.us/key-performance-measures/

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Projects & Planning," accessed Oct 14, 2015, http://projects.arlingtonva.us/types/

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Complete Streets", accessed Oct 13, 2015, http://projects.arlingtonva.us/programs/complete-streets/

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Neighborhood Complete Streets Commission (NCSC)," accessed Oct 12, 2015, http://commissions.arlingtonva.us/neighborhood-complete-streets-commission/

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ritch Viola, telephone interview by Christine Sherman, Oct 2, 2015.

- ↑ Arlington County Commuter Services, "Arlington Recognized as Gold-Level Walk Friendly Community," accessed Oct 13, 2015, http://www.walkarlington.com/pages/about/arlington-recognized-as-walk-friendly-community/

- ↑ The League of American Bicyclists, "Current Bike Friendly Communities 2014," accessed Oct 12, 20145, http://bikeleague.org/sites/default/files/Fall_2014_BFC_List.pdf

- ↑ Arlington Transit, "ART and Metrobus Routes Serving Arlington," accessed Oct 13, 2015, http://www.arlingtontransit.com/pages/map/

- ↑ a b c d e f g Michael Connor, interview by Houda Ali, Courthouse Plaza, Arlington, Virginia, Oct 6, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Luis Araya, interview by Eric Stahl, Courthouse Plaza, Arlington, Virginia, Oct 9, 2015.

- ↑ a b c County of Arlington, Virginia, Arlington County Board, "Arlington County Code," accessed Sep 29, 2015, http://countyboard.arlingtonva.us/county-code/.

- ↑ Arlington Historical Society, "History of Arlington County," accessed Oct 16, 2015, http://www.arlingtonhistoricalsociety.org/learn/history-of-arlington-county/alexandria-county-district-of-columbia/

- ↑ a b c County of Arlington, Virginia, "Participation Leadership and Civic Engagement," accessed Oct 10, 2015, http://topics.arlingtonva.us/place/

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Civil Engineering Plans," accessed Oct 11, 2015, http://topics.arlingtonva.us/building/civil-engineering-plans/

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "County Board," accessed Oct 13, 2015, http://countyboard.arlingtonva.us/about/

- ↑ New York City, Department of Transportation, "The Economic Benefits of Sustainable Streets," Dec 13, 2013, http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/dot-economic-benefits-of-sustainable-streets.pdf, pg. 5

- ↑ New York City, Department of Transportation, pg. 8

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Advisory Groups & Commissions," accessed Oct 12, 2015, http://commissions.arlingtonva.us/

- ↑ "Commonwealth (U.S. State)," Wikipedia, accessed Oct 10, 2015, wikipedia:Commonwealth (U.S._state)

- ↑ Virginia General Assembly, Constitution of Virginia, amended 2011, art. I, sec. 2

- ↑ a b County of Arlington, Virginia, Office of the County Manager, "Participation, Leadership and Civic Engagement: Report to the County Board," Dec 2012, http://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2014/11/PLACE-Report-FinalWithPageNo.pdf

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, Department of Environmental Services, Division of Transportation, Development Services Bureau, "Transportation Right of Way Guide," accessed Oct 10, 2015, http://topics.arlingtonva.us/permits-licenses/transportation-right-way-permit-guide/

- ↑ Bailey, p. 19

- ↑ Virginia General Assembly, Code of Virginia, amended 1950, title 15.2, http://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title15.2/

- ↑ United States Census Bureau, "State & County QuickFacts: Arlington County, Virginia," accessed Oct. 10, 2015, http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/51/51013.html

- ↑ United States Census Bureau, "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2009-2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates," accessed 10/12/2015, http://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/13_5YR/DP03/0100000US%7C0400000US51%7C0500000US51013

- ↑ United States Census Bureau, "Selected Social Characteristics: 2009-2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates," accessed 10/12/2015, http://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/13_5YR/DP02/0100000US%7C0400000US51%7C0500000US51013

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Major Statistics," 2013, accessed Oct 12, 2015, http://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2014/03/Major-Statistics-2013.pdf

- ↑ Ethan Rothstein, "Arlington Ranks as Richest County in America", ArlNow, Sep 23, 2013, https://www.arlnow.com/2013/09/23/arlington-1-nationwide-in-family-income/

- ↑ Virginia General Assembly, 1988 Session, Code of Virginia, Amended 1988, Title 62.1, Chapter 3.1, Article 2.5, "Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act," http://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacodefull/title62.1/chapter3.1/article2.5/

- ↑ United States Congress, 92nd (1972), Statute 86-816, "Federal ", http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg816.pdf

- ↑ Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, "Protecting Local and Regional Water Quality: Stormwater Management in the Metropolitan Washington Region," Nov 2013, https://mwcog.org/environment/water/Stormwater%20factsheet%20-%20REVISED_110513.pdf

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "MS4 Permit," accessed Oct 14, 2015, http://environment.arlingtonva.us/stormwater-watersheds/management/ms4-permit/

- ↑ a b United States, Environmental Protection Agency, "Innovative Stormwater Management Standards and Mitigation," accessed Oct 14, 2015, http://water.epa.gov/polwaste/npdes/stormwater/Innovative-Stormwater-Management-Standards-And-Mitigation.cfm

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, Department of Environmental Services, " Fiscal Year 2013 Annual Stormwater Management Program Report," Sep 30, 2013, https://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2013/10/Stormwater-Permit-Annual-Report.pdf, pg. 32

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, County Code, Chap. 26, Sec 26-9, "Penalties," http://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2014/01/County-Code-26-Utilities.pdf

- ↑ a b County of Arlington, Virginia, "Building," accessed Oct 14, 2015, http://topics.arlingtonva.us/building/

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Pavement Marking Standards," Nov 2013, http://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2013/11/DES-Pavement-Marking-Standards.pdf

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Master Transportation Plan: Bicycle Element," Feb 2014, http://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2014/02/DES-MTP-Bicycle-Element.pdf

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Rossyln Sector Plan," July 17, 2015, https://projects.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2015/07/Final-draft-Rosslyn_Sector_Plan-Posted_07-17-2015.pdf

- ↑ a b County of Arlington, Virginia, "Traffic Signal and Street Light Specifications," Dec 2013, http://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2013/12/Traffic-Signal-and-Street-Light-Specifications.pdf

- ↑ County of Arlington, "Traffic Signal and Street Light Specifications," pg. 113

- ↑ County of Arlington, "Traffic Signal and Street Light Specifications," pg. 112

- ↑ County of Arlington, "Traffic Signal and Street Light Specifications," pg. 103

- ↑ County of Arlington, Virginia, "Traffic Signs," accessed Oct 13, 2015, http://transportation.arlingtonva.us/streets/traffic-signs/

- ↑ a b County of Arlington, Virginia, “PhotoRED,” accessed Oct 14, 2015, http://police.arlingtonva.us/photored/

- ↑ Lt. Ken Dennis, email interview by Houda Ali, Oct 16, 2015

- ↑ a b c d County of Arlington, Virginia, County Code, Chap. 15, "Noise Control," Jan 2014, http://arlingtonva.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2014/01/County-Code-15-Noise-Control.pdf