Transportation Planning Casebook/Vancouver Skytrain

Summary

Vancouver has a relatively extensive transit system that is best known for the Skytrain system. Skytrain consisted originally of raised tracks on which trains ran using a system similar to a typical subway. In subsequent expansions it also includes underground tunnels, with some at-grade sections; however it is primarily a grade-separated form of mass transit. A transit solution between central Vancouver and the University of British Columbia (UBC) is currently being considered, with Skytrain being one of the primary candidate modes. There are a number of issues that have arisen when planning this development, and we present these issues as a launching point for discussion of universal issues when considering any transportation system. In particular, we analyze different transit technologies and the governmental structure for ownership and funding sources of the mass transit in the area. We look at some of the tradeoffs a planner must make when designing a system and the stakeholders that are involved in such a project.

Additional Readings

- A Cost Comparison of Transportation Modes

- Long-Term Change Around SkyTrain Stations in Vancouver, Canada: A Demographic Shift-Share Analysis

- Citizens/businesses against development

- Phase 2 design guide for UBC line

Timeline

- 1997 - The Vancouver City Council’s “City Transportation Plan” is approved which includes a rapid transit plan for the Broadway Corridor

- 2008 - British Columbia releases their Provincial Transit Plan, outlining plans for a number of new developments including a skytrain line connecting to the UBC.[1]

- May 21, 2010 – Phase 1 of the UBC Line Rapid Transit Study closed which consulted stakeholders and professionals to determine a list of possible alternatives for the UBS Line.[2]

- April 22, 2011 – Phase 2 of the UBC Line Rapid Transit Study closed which included consulted the public opinion on 7 possible alternatives.[2]

- TBA - Phase 3 of the UBC Line Rapid Transit Study will commence. Using the selected transit option a budget, a timeline, design development and phasing will be created.

Narrative

Vancouver is the third largest metro area in Canada. It is located along the west coast of Canada with the Pacific to the west, the United States to the south and the North Shore Mountains to the north.[3] The Vancouver area has seen rapid growth in the past few years. It is estimated that the metro area’s population will increase by about 50% by the year 2041.[4] Because of the geographical constraints of the area much of this growth is happening through increasing population density instead in favor of increasing developed land area. The growth and density of the area over the years has allowed for the development of an intricate mass transit system including buses, ferries and light rail transit.

History of transit and governance in metropolitan Vancouver

Original transit system (streetcars)

Mass transit in Vancouver began in the early 1890s with the installation of electric streetcars along 9 km of track in the city center. The system expanded rapidly through WWI, and was vital to residents affected by the Great Depression needing a cheaper form of transport. The system was privately owned and operated by the British Columbia Electric Railway (BCER).[5]

Electric buses (trolley buses)

Motor buses were used to supplement streetcar service by the 1920s, but the relatively low power of diesel buses at the time resulted in the implementation of electrified bus (trolleybus) service. By 1955, the electric streetcar fleet was retired and Vancouver possessed the largest trolleybus fleet in Canada.

In 1961, the provincial government took over ownership of the privately run transit system and created BC Hydro, a government owned Crown corporation.

In 1979, the provincial government created the Urban Transportation Authority, in order for local governments to have an increased role in providing transit service. The UTA became BC Transit in 1982, and in 1999, greater Vancouver created the Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority, later known as Translink, which now oversees the operation of the entire transit system for the Vancouver region.[5]

Skytrain

Vancouver had been rethinking its approach to large scale mass transit since the retirement of the streetcar fleet in the 1950s. Worsening congestion in the metro Vancouver area, coupled with the city being awarded the 1986 World Exposition, which focused on Transportation and Communication Vancouver, gave the city the opportunity to build its first form of rapid transit, Skytrain.[6]

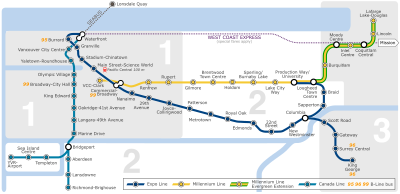

The first Skytrain line - the Expo Line - opened in 1985 and currently connects Vancouver to Surrey. The Millenium Line was added in 2002 and circulates Vancouver and the adjacent city of Burnaby.[6] The most recently completed line, the Canada Line, was opened in 2009 connecting the Vancouver airport and the southern suburbs of Vancouver to the central transportation hub, and is currently 3 years ahead of ridership projections.[7] An extension of the Millenium Line, named the Evergreen Line, is currently beginning construction and is expected to open in 2014/2015. This line will connect the Millenium Line to the eastern suburbs and terminate at Douglas College.[8]

In 2010 the Skytrain system carried people for 347 million total trips and had a net revenue of about $244 million.[9] It uses a zone-based pricing scheme, where travel within a single zone costs $2.50, whereas crossing through all 3 zones during a trip costs $5.00.[10]

UBC Line

The Broadway Corridor connects Central Broadway with the University of British Columbia. The Central Broadway area is the second largest job center in the Vancouver metro area while the University of British Columbia in Vancouver is one of the county’s largest colleges. There are 100,000 daily bus trips taken along this corridor which leads to overcrowding and inconsistent timing. During peak times buses run along this route almost every 90 seconds which adds to the already congested area.[2] An upgrade to the transit system along the Broadway Corridor is severely needed.

Annotated List of Actors (Stakeholders)

Business Interests

The general opinion of businesses is that mass transit would be good for the overall economic health of the area, however the majority are against a Skytrain system. One of the main arguments against a Skytrain is the disruption caused by construction, which in order to be kept affordable would likely use the cut-and-fill technique. This technique was used in the construction of the Canada Skytrain line where businesses located in the Cambie Street area ended up suing the provincial government for compensation for the economic losses suffered.[11] Businesses fear similar economic hardships and bankruptcies, which would likely occur if an underground Skytrain line were to be constructed. One merchant, who went bankrupt during the construction of the Canada line, spoke at a public hearing stating “What’s happening along here is exactly what happened on Cambie Street.”[11] This opinion is one held by the Business and Residents Association for Sustainable Transportation Alternatives (BARSTA), who also questioned the long term benefits of Skytrain on the UBC line, with one member stating “We want to make some suggestions about transit alternatives that would be best for not only improving transit, but for respecting and enhancing our communities and local businesses”.[11] The businesses of the organization favor less expensive transit options that provide more access to local businesses, such as light rail or improved busing.[12] By providing more visibility to the local businesses due to being at-grade there would be less disconnect from the Broadway business district than a more separated system.

University of British Columbia

The majority of the users of the current 99 line are University of British Columbia. Upgrading the transit on this line would lower commuter times for students and faculty. This project would give students who live on campus a better connection with the Vancouver area including the international airport. The University of Vancouver has been named one of the most sustainable campuses in North America by the U.S. Sustainable Endowments Institute. Improving transit in the area would help the keep the university on this list.[13]

Citizen Groups

SPEC

The British Columbia-based Society Promoting Environmental Conservation (SPEC) was founded in 1969 to address environmental issues in British Columbia in general and urban areas in particular. SPEC sent out a press release advocating for the reallocation of transportation funds away from highway transportation projects in order to expand transit projects in the metro Vancouver area. In a press release from 2010, SPEC cites previous years’ increased carbon emissions and increased per-capita gasoline sales as evidence that the province is failing to meet their climate change goals. Since they claim 40% of carbon emissions are transportation related, SPEC suggests that investing in transit will shift mode choice to transit, thereby reducing carbon emissions. SPEC also advocates for transit as a means to drive economic development.[14]

Canadian Taxpayers Federation

The Canadian Taxpayers Federation is a citizen advocacy group that advocates for lower taxes and greater efficiency and accountability in government. In Vancouver, they have written in opposition of spending over $100 million on fair gates at Skytrain stations as a method to combat fare evasion. Riders currently operate on the honor system and face a fine for not possessing a valid ticket. As an alternative, the CTF supports greater fines and enforcement to reduce fare evasion and increase fare revenue. In addition, CTF opposes the high rate of gas taxes, particularly in British Columbia, where gas taxes are highest.[15][16]

Sustainable Transportation Coalition

An influential group of planners, architects, and environmentalists is campaigning to persuade local and provincial governments to implement the funding measures necessary to accomplish the goals identified in Metro Vancouver’s 2040 Plan. The Coalition is comprised of a number of citizens active in transportation issues across the province, and is headed by Peter Ladner, a 2008 mayoral candidate for Vancouver.[17][18]

CUTA - Canadian Urban Transit Association

The Canadian Urban Transit Association is a trade group that promotes transit infrastructure and the transit industry as a whole within Canada and believes in transits ability to contribute to quality of life in the Canadian communities that transit serves. Its members consist of professionals working or affiliated with the transit industry. CUTA publishes a number of reports to advocate and promote transit in Canada, including their “Transit Vision 2040” report, that identifies major themes in improving transit effciency such as improving service and customer relations, being environmentally and fiscally sustainable, and advancing support for transit in Canadian communities.[19]

Government Agencies

Provincial Government

The government of British Columbia has been very involved with the transit system of the metro Vancouver area. Translink was set up by the province to bring together the municipal governments and local transit companies and took over many transit operations previously held by the province. British Columbia has been one of the main financiers of previous transit projects, including Skytrain, and has used transit changes to meet its environmental goals.[1]

National Government

The Canadian government has been supportive of the Skytrain system in the past. It has contributed $1.1 billion dollars to the system through the Building Canada Fund, Public Transit Capital Trust and other federal funding programs. Nina Grewal, a member of Canadian Parliament, has said “…Our government is proud to support environmentally sustainable municipal infrastructure, like the Skytrain, which contributes to cleaner air and reduced greenhouse gas emissions, improving the environment and benefiting all Canadians,”.[20] Although the Canadian government would be supportive of any increase in mass transit that would decrease emissions the federal government, the Skytrain system has been singled out by the federal government time and time again because it is a large scale, technologically advanced mass transit option.

Translink

In 2010, Translink received 32% of its revenue from transit fees, which was its largest single source of revenue.[9] Consequently, Translink has a strong interest in any projects that would increase the income from transit fares as a result of expansion of the system. A transit system would also likely increase the property values near the line and change consumer fuel use which would effect Translink's primary sources of income (property and fuel taxes, which comprise 45% of Translink’s revenue stream).[9] In addition to having large impacts on the potential revenue of the company, Translink would also have to make a large initial investment in the line. While the project is still too early in development to determine funding sources they have historically provided a large share of the funding for similar projects. For example, for the Evergreen Line currently under construction Translink has agreed to contribute $400-Million of the total $1.4-Billion project cost, or about 29% of the total.[21] Less concretely, Translink is the primary entity in planning and operating the line, so any positive or negative aspects of the UBC Line will reflect most directly on them. As a result, Translink has a large stake in the success or failure of the project and is less concerned about any one particular technology.

Clear Identification of Policy Issues

Planning

Alternatives Analysis

For most large-scale projects an alternative analysis, or a weighing of options to obtain the goal most efficiently, is conducted. Alternative analyses require a commitment of time and money from the stakeholder(s) funding the given project. Without the analyses, the planning process would be rather impractical. In the case of the projected UBC line there has been extensive alternative analysis conducted. This has been funded by two stakeholders: Translink and the Province of British Columbia.[22]

The first alternative proposed for the system is a Bus Rapid Transit line running a linear route along Broadway. The buses would run along the center of the street, with stations being located in the median and connected by crosswalks. The line would offer access to three different north-south running bus lines. This option is the least expensive but also the slowest. The capital cost of the BRT alternative is $350 million for the diesel buses, and $450 million for the trolley buses. These costs are less than half of the other alternatives because very few infrastructure changes would need to be made. One-way trip time from end to end would take approximately 33 minutes. The proposed ridership for the BRT option is 75,000 trips per day. Proposed trips per day for other alternatives are at 100,000 or more.[23] This implies that the BRT alternative would be inadequate given the demanded travel needs of the line.

There are two LRT alternatives. The first LRT alternative includes two options, labeled “A” and “B.” The A option would be aligned on Broadway Ave for the entirety of the line. This option would be faster than the B option, which would loop up to the VCC Clark Station and Great Northern Way Campus. Option A would most likely provide service to UBC students commuting to campus, while option B would also be serving tourists, shoppers, and Great Northern Way students. The one-way trip travel time for option A would be approximately 26 minutes and option B would be 29 minutes. The capital costs for the A and B options would be at $1.1 billion. The projected trips per day for option A is 99,000. and 109,000 for B.[23] This alternative fits in better with the 100,000 trips per day goal, although the capital and incremental costs being considerably larger. Signaling priority would be given to the LRT alternative, although this would only cut trip time by a few minutes.

The Second LRT alternative proposes more stops, because of the B option encompassing a larger loop. The B option route connects with the A at the Arbutus stop, about halfway along the total line. This alternative allows for increased development along Central Broadway and northward. Capital costs increase to $1.38 billion for the A option, and $1.48 billion for the B option. Daily projected ridership levels stay about the same for option A as expected, but rise to 116,000 trips per day in the extended option B.[23]

RRT, or Rail Rapid Transit, is yet another option for the UBC line. The plan proposes tunneled RRT for most of the line, with only a small portion of the line being elevated. This alternative poses two options; with the routes being similar to the previously proposed alternatives. Option A would run exclusively underground. Option B would be an extension of the Millennium Line, and would begin elevated until reaching the Great Northern Way campus. The capital costs for this alternative are large, with option A totaling $3.2 billion and option B $2.9 billion. This is undoubtedly because of the switch of grades along the B route. Estimated ridership levels are 137,000 for option A, and 146,000 for option B. Riders of these routes would experience 20 minute trip times one-way.[23]

There are two combination alternatives in regards to RRT. The first alternative being predominantly LRT, with tunneled RRT splitting off at the Arbutus stop. This alternative boasts the highest potential ridership levels, with daily estimates reaching 145,000 trips. Because of the modal interchanges required, the trip time for this alternative would rise to 25-27 minutes. The capital cost would be $2.4 billion. Infrastructure would need to be changed to allow for this alternative. Elevators or stairs would be necessary for the tunnel or raised RRT.[23]

The other combined alternative features BRT for the entire Broadway line, with RRT (connected from the Millennium Line) running parallel along Broadway until at last an interchange to BRT must be made at the Arbutus stop. Capital cost for this alternative would be $1.9 billion, with most of the cost coming from the extension of the Millennium Line to Arbutus. The incremental operating cost would be $4 million. This alternative is expected to serve 138,000 trips per day. The one-way trip time would be increased to 32 minutes along the line.[23] This alternative would potentially relieve congestion because of its interesting alignment. The multi-modal system of RRT and BRT would give riders choices.

The final alternative simply offers improved bus service between UBC and Commercial Broadway. Named “Best Bus Alternative,” the plan is to increase frequency on multiple routes between the two points, as well as provide express bus service. Changes needed to implement the Best Bus alternative are relatively simple compared to the other alternatives. An increased deployment of buses would be needed, as well as the provision of real-time schedules and increased shelters. The trip time between UBC and Commercial Broadway would be approximately 30 minutes. The capital cost of this alternative would be $325 million, with incremental operating costs being $18 million. This alternative is the cheapest, easiest to deploy and easiest to maintain. The projected ridership level, like the first alternative, is at 75,000 trips per day. This is almost half that of the first combination alternative.[23]

Funding

As with any upgrade to a transit system, cost is an important issue and one of the main factors in the decision of how to fix the transit problem in the Broadway Corridor. The seven options outlined in the alternatives analysis have costs varying from $325 million to $3.2 billion in capital costs with the rail rapid transit option being the most expensive and the best bus option being the least.[2] Different funding options are currently being looked at for the region including federal and provincial funds, tax increases and increasing current transit fares.

The majority of the funding for large transit projects in the Vancouver area has come from different federal and provincial funding programs and Translink. These were three of the four largest contributors to the $1.9 billion initial cost of Skytrain’s Canada line with 22% federal money, 12% provincial money and 17% from Translink.[24] The other contributor was the international airport which was a main destination on that line. These funding patterns are also the case for the upcoming Evergreen line due in 2014. It would be logical to assume this will happen for similar future projects, such as the UBC line.

An increase in gas taxes of two cents per liter is currently being proposed to help fund the UBC line and other Translink projects. This idea has been met with opposition from the public. British Columbia already has the highest gas taxes of any Canadian province with 33.6% of the cost of gas being taxes while having the second highest total cost for gasoline. Adding more taxes would only increase the gap between the second highest province, Quebec.[25]

Other ways to raise money for this and other projects in the Vancouver metro area have been suggested and implemented. The governor of Surrey, a city located south of Vancouver, has suggested selling the naming rights to different Skytrain stations to raise money.[26] Others see increasing property taxes and current transit fares as an option. Upgrades to the current systems are also being looked at to increase ridership and funds. For example, new fare gate systems are being installed in the current Skytrain stations which should help stop fare jumpers.

Cost Considerations

The capital costs for transportation modes such as streetcar, LRT and Skytrain are relatively easy to determine because the large initial investment to build the transportation infrastructure (tunnels and elevated tracks, vehicles, stations etc.) is generally tied directly to the project. However, many costs associated with personal automobile, local bus service and to a lesser extent BRT and trolley bus are more difficult to determine because they operate on existing roadways, the construction and maintenance of which are not included in most cost calculations for these modes.

Environmental Concerns

Studies by leading experts indicate that climate change may impose significant economic, social and environmental costs and cause catastrophic damage. In 2008, the most recent year for which there are records, greenhouse gases increased in BC despite a national trend of decreasing emissions. 2009 saw per-capita gasoline sales in BC rise almost 10 percent which was the largest single-year increase for the province in at least 30 years.

SPEC is calling on the province to scale back or cancel the many highway expansion projects that are either in process or planned. This would free up well over a billion dollars for public transportation, education and social programs

Legislation now exists that requires municipalities and regions to arrange land uses and transportation systems in a manner that reduces greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (ie. British Columbia’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Act). The use of transit, which was heretofore considered solely from the perspective of reducing auto dependence and providing transportation equity to the disadvantaged, now has a broader mandate to help governments meet their GHG targets.

Modes such as LRT and Skytrain have very low external costs because the infrastructure for these types of projects generally have to be built from scratch so the costs are already included in their higher initial capital costs. If most trips in the region are short then the rationale for investment in trams is overwhelming. If all trips are long then the rationale for the very expensive Skytrain system may still hold sway.

Public Safety

Each of the 7 alternatives for the Broadway Corridor transit upgrade comes with their own set of safety concerns. Buses, LRT, or any other form of transit using the same grade as pedestrians, bicycles, and automobiles will face a future of potential collisions. The option for a separate-grade transportation system would not face these same concerns, as they have their own right of way, as well as built in sensors that detect, and warn of, any impediment along the track. However, other safety concerns about the lack of natural surveillance arise when considering below grade boarding stations. To appease such safety concerns, Translink currently has its own fully accredited police agency called the South Coast British Columbia Transportation Authority Police Service (link). This agency would be involved in whichever alternative is chosen to help enforce fairs, increase surveillance, and reduce crimes.

Aesthetics/Design

The different transit alternative designs could have an effect of the overall look of the area. The Best Bus option would only increase the number of busses on the current roadway while the Bus Rapid Transit option would require two paved lanes of its own. The light rail options would also require a lane for each direction of light rail traffic but could be designed as grass tracks adding some vegetation to the streets. This would be a visual reminder of the environmental benefits of light rail. Both the Bus Rapid Transit option and light rail options would require new stop areas, possibly with shelters, to be added to the area. Depending on the design these could either enhance or reduce the aesthetics of the area. The three options that contain rail rapid use tunnels and would not disturb the roadway or aesthetics of the Broadway corridor.[2]

Project Future

The future of the transit in the Broadway Corridor is not well defined. An alternative from the seven proposed options will be chosen and included in the Translink 2045 report due out in August 2013.[27] No funding is being planned specifically for this project but for the larger Translink and Government funds and trusts that would likely be used to finance the project. No timeline or deadlines for the project have been set.

References

- ↑ a b Provincial Transit Plan. Rep. Ministry of Transportation, British Columbia, 2008. Web. 16 Sept. 2011. [1].

- ↑ a b c d e “UBC Line Rapid Transit Study – Phase 2.” Translink.ca. Translink. Web. 15 August 2011. [2].

- ↑ Meligrana, John F. “Toward Regional Transportation Governance: A Case Study of Greater Vancouver.” Transportation 26. 4 (1999): 359-398. Print. [3].

- ↑ “Future Population Growth in Vancouver.” Vancouver.ca. City of Vancouver. 4 August 2010. Web. 15 August 2011. [4].

- ↑ a b "BC Transit History." BC Transit. British Columbia Transit Service. Web. 17 Sept. 2011. [5].

- ↑ a b "Vancouver SkyTrain Network." Railway Technology. Web. 16 Sept. 2011. [6].

- ↑ Nagel, Jeff. "Rise in Transit Use Called Olympic Legacy." BCLocalNews.com - Local News. Surrey Leader, 10 Feb. 2011. Web. 16 Sept. 2011. [7].

- ↑ Evergreen Line - Connecting Coquitlam to Vancouver via Port Moody. British Columbia Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure. Web. 16 Sept. 2011. [8].

- ↑ a b c "Translink 2010 Annual Report." Translink. 16 Sept. 2011. [9].

- ↑ "Single Fares." Translink. Translink. Web. 16 Sept. 2011. [10].

- ↑ a b c McElroy, Justin. "Kits. Residents Rally against a UBC Skytrain Line." The Ubyssey Student Newspaper. University of British Columbia. Web. 16 Sept. 2011. [11].

- ↑ "BARSTA, Proposed Broadway Line, and Developments around Canada Line." The Vancouver Observer. 16 Sept. 2011. [12].

- ↑ “UBC Line Key to Increased Transit Ridership and Campus Sustainability.” www.publicaffairs.ubc.ca. University of British Columbia. 11 December 2008. Web. 16 September 2011.[13]

- ↑ Society Promoting Environmental Conservation. “SPEC Calls for Transportation Reallocation” Press Release. September 21, 2010. [14]

- ↑ Bader, Maureen “TransLink to spend $100-million to save $6-million”. Canadian Taxpayer Federation. [15]

- ↑ CBC News. “Gas tax highest in Vancouver: advocacy group.” May 26, 2011. [16]

- ↑ Bula, Frances. "Transit advocates launch campaign for provisional property-tax hike." The Globe and Mail. September 11, 2011 [17]

- ↑ "The South Fraser Blog: Support of Increased Gas Tax and Other Funding Measures for TransLink." [18]

- ↑ Canadian Urban Transit Association. “Transit Vision 2040. Moving Forward: Vision to Action. 2010 Progress Report Summary” [19]

- ↑ “Federal Investments Guarantee Bright Future for Skytrain.” Ninagrewal.ca. 17 August 2011. Web. 16 September 2011. [20].

- ↑ Sinoski, Kelly. "Mayors Vote to Hike Gas Tax to Fund Evergreen Line." The Vancouver Sun. The Vancouver Sun, 7 July 2011. Web. 16 Sept. 2011. [21].

- ↑ “UBC Line Rapid Transit Study Evaluation Summary.” Translink.ca. Translink. Web. 11 April 2011. [22]

- ↑ a b c d e f g “UBC Line Rapid Transit Study Design Guide.” Translink.ca. Translink. Web. March/April 2011. [23]

- ↑ “PM pledges $350M for Evergreen Rapid Transit Line.” Cba.ca. Canadian Bankers Association. 26 February 2009. Web. 15 September 2011. [24].

- ↑ Fildebrandt, Derek. “13th Annual Gas Tax Honesty Day Background Information.” Cba.ca. Canadian Taxpayer Federation. May 2011. Web. 16 September 2011. [25].

- ↑ Sinoski, Kelly. “Sell naming rights to Skytrain stations, says Surrey mayor.” The Vancouver Sun. 24 July 2011 ed. Web. [26].

- ↑ “2012 Base Plan and Outlook.” Translink.ca. Translink. Web. 16 September 2011.[27]