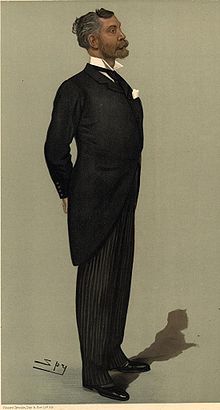

The Rowers of Vanity Fair/Vincent E

Vincent, Edgar (Viscount D’Abernon)

[edit | edit source]“Eastern Finance” (Spy), April 20, 1899

[edit | edit source]

A parson and the eleventh Baronet of his family became his father two-and-forty years ago: and when he had done those things which he ought (or ought not) to have done at Eton -- among others passing head as a Student Dragoman and not taking up the appointment -- he joined the Coldstream Guards. After five years of service he became Secretary to Lord Edmond Fitzmaurice, Queen’s Commissioner on the East Roumelian Question; and so began his real acquaintance with the East. He got on; and after being a Commissioner for the Evacuation of Thessaly, President of the Council of the Ottoman Public Debt and Financial Adviser to the Egyptian Government, he was made Governor of the Imperial Ottoman Bank. He holds various Turkish Orders; he has been guilty of “A Grammar of Modern Greek” which now plagues the members of the Athenian University; he likes yachting; he cycles, and he can play billiards. He left Eton with the manuscript of his Greek Grammar; and consequently he left the Service with the name of “Sophos”: which still sticks to him. Nevertheless, he escaped through the roof of the Ottoman Bank during the great massacre. He has a unique tennis court of his own at Esher.

He is the husband of one of the most beautiful women yet born.

Edgar Vincent (1857-1941) rowed no. 5 for Eton in the 1874 Grand and Ladies’.

Lord Kinross, historian of the Ottoman empire, recounted the escape through the roof of the bank as follows, in the context of rising Turkish-Armenian tensions:

In August 1896, the succession of Armenian massacres culminated in Istanbul itself. Once again, as in the previous year, the Turkish authorities were presented with a pretext for action by an Armenian revolutionary group. A small body of Dashnaks was so bold as to enter the Ottoman Bank, the stronghold of European capitalist enterprise, during the lunch hour, for the ostensible purpose of changing money. Porters accompanying them carried sacks which contained, so they pretended, gold and silver coinage. Then at the blast of a whistle twenty-five armed men followed them into the bank, firing their guns and revealing that the sacks in fact were filled with bombs, ammunition, and dynamite. They declared that they wee not bank robbers but Armenian patriots, and that the motive of their action was to bring their grievances, which they specified in two documents, to the attention of the six European embassies, putting forward demands for political reform and declaring that, in the absence of foreign intervention within forty-eight hours, they would "shrink from no sacrifice" and blow up the bank.

Meanwhile, its chief director, Sir Edgar Vincent, had prudently escaped through a skylight into an adjoining building. While his colleagues were held as hostages, he thence proceeded to the Sublime Porte [i.e. the Turkish authorities]. Here he ensured that no police attack should be made on the Dashnaks while they remained in the bank. Thus he secured for them permission to negotiate. The negotiator was the First Dragoman of the Russian embassy, who after gaining fro them a free pardon from the Sultan and permission to leave the contry, addressed them at length and with some eloquence. Finally, with assurances of talks to come, he persuaded them to leave the bank. Retaining their arms but relinquishing their bombs, they proceeded quietly on board Sir Edgar Vincent's yacht, later to be conveyed into exile in France.[1]

Shortly after his appearance in Vanity Fair, Vincent went to Parliament as a Conservative. He was defeated in 1906 and again in 1910, ending an electoral career “for which indeed he was not well fitted for his rapidity of perception made him see every side of a question and stood in the way of a wholehearted accpetance of general principles.”[2] From 1912-17 he served as chairman of the Royal Commission on imperial trade, and during the war as chairman of the Central Control Board, where he imposed heavy taxation on alcohol. In 1920 Lloyd George appointed him ambassador to Germany in recognition, in Lord Curzon’s words, that the post at that delicate time required “a close familiarity with economic and financial subjects and wide experience in dealing on friendly terms with various classes of men.” During six stressful years in Berlin, Baron D’Abernon -- he was made a peer in 1914 -- dealt with reparations, disarmament, occupation of German territory, French security, and the attempted formation of a new European order, culminating in the 1926 Treaty of Locarno that admitted Germany to the League of Nations. On return to England, he was made Viscount and spent several years as head or director of varied agencies, organizations, and philanthropies such as the National and Tate Galleries, the Lawn Tennis Association, the Race Course Betting Control Board, the Medical Research Council, the National Institute of Industrial Psychology, and the Royal Mint Advisory Committee.

The “most beautiful woman yet born”? It was Lady Helen Venetia Duncombe, his wife for fifty-one years, daughter of the first Earl of Feversham.

To a Henley Minstrel

[edit | edit source]The banjo “was quite tolerable when heard across the water,” recalled Max Pemberton of 1880s Henley, though by 1936 when he published his autobiography “[t]he gramophone has squashed the itinerant musician and the casual ballad-monger has dust in his mouth.” But such uninvited songsters were still thriving in 1904, when Vanity Fair (July 14, 1904) offered these anonymous lines:

- (After Swinburne.)

- Black bawler of blithering ballads,

- Swart (soi-disant) son of the States,

- Why poison our lobsters and salads,

- Turn the strawberry sour on our plates?

- Why make heavenly Henley the target

- Of the song (save the mark!) that you shout?

- Why on earth don’t you go down to Margate?

- Get out!

- When we’re prone in a punt on the river

- Or coiled in a cosy canoe,

- The sweet summer stillness you shiver,

- You cork-burning criminal, you!

- If my bank-balance bulged to a billion,

- Not one small, single sou would I give

- For the songs which you steal from Pavilion

- And Tiv.

- Dark dealer in drivelling ditties,

- Devoid both of tune and of sense,

- In which not a shadow of wit is,

- Think well ere you plague me for pence:

- I’m not one who sticks at a trifle;

- I know neither pity nor fear,

- And to Henley I’m taking my rifle

- Next year.