Sustainability and Sense of Place in the Sonoran Desert/Baja Peninsula & Sea of Cortez

Introduction

[edit | edit source]Members

- Henry Merrill

- Blanca Soto 7

- Vianna Trigueros

- Martha Chacon Martin

The Baja California Peninsula has always been a mysterious and exotic land full of wonder. Filled with cave paintings, stories of lost tribes, exotic flora and fauna, and more, the region still to this day holds much of the mystique it likely did for Spanish explorers landing in 1534. [1] As notable anthropologist and explorer Arthur W. North remarked:

"Baja California, until half a dozen years ago, possessed the doubtful honor to be almost the least known territory in the world, with the exception of the polar regions and some few deserts and inland places, difficult and dangerous of access." Thus a noted geographer characterized the California peninsula in 1897, and thus I found it a few years later upon undertaking the compilation of its history and the exploration of its interior fastness. [1]

North continued this exploration and documentation of the great peninsula, as have many others. However, he nor the Spanish, were among the first people to explore this great land. Shell middens found near Espíritu Santo Island indicate that human beings existed there as long as 35,000 B.P. [2]

While our book focuses primarily on concepts and connections of the natural world, we would be remiss if we didn’t briefly discuss the indigenous populations of these regions. Not only because of their integral contributions to regional culture and history, but perhaps because by remembering and studying their lifestyles and connection to nature we may begin to further identify and understand the shortcomings of our current relationship with the ecological world.

Three main tribes occupied the peninsula when the Spanish first arrived, the Cochimí, Guaycura, and Pericú. These great tribes lived sustainably off the land, often relying on the exploitation of seasonal bounties. [3] [4] [5] Data reveals significant cultural homogeneity between the Cochimí and Guaycura, while the Pericú remain a mysterious and isolated lost culture. [6] The origins of the once-great Pericú remain a mystery to anthropologists. Much is still to be learned about these people whose dolichocranic traits have resulted in theorizing that they may have been an isolated relic population of an early coastal migration to North America. [3] What is known about the Pericú and the other groups is that when the greatest threat they had ever faced arrived in the form of Europeans, they did not unite and continued infighting, with the Pericú going as far as to enlist early explorers in attacks against the Guaycura, who may have been encroaching into their territory.

Today the Sonoran Desert and Baja California face new threats. The very caves that yielded information about these tribes are currently threatened by tourist development. [3] Throughout our portion of this book you will find highlighted some of the most amazing and important features of the Baja region of the Sonoran Desert. This section is brought to you with the hopes of giving the reader the opportunity to explore this great desert and peninsula in a fresh way, with the original sense of adventure, but with an eye for sustainability and with a sense of place. By doing this we hope we can be a small part of uniting people to help make sure both the Sonoran and our planet overcome the threats they now face. We hope you enjoy.

Biodiversity

[edit | edit source]Baja California Pronghorn

[edit | edit source]The Baja California pronghorn (Antilocapra americana peninsularis) is a subspecies of pronghorn endemic to the Baja California Peninsula. The pronghorn is a critically endangered subspecies with only an estimated 200 animals remaining in the wild.[7] These animals were once found in great abundance at least as far south as Cuidad Insurgentes, BCS.[8] These iconic animals are the only remaining survivors of the animal family, Antilocapridae. Antilocapridae consisted of hoofed animals, existing primarily in the Pleistocene age (10,000 to 1.8 million years ago).[9] This prehistoric survivor now faces extinction in the Anthropocene epoch, primarily from man-made causes.

Habitat and Life Cycle

[edit | edit source]The Baja California pronghorn now only exists in the El Vizcaíno Desert Biosphere Reserve of Baja California and in the Valle de Los Cirios Reserve of Baja California, Mexico. The animals once roamed largely over central Baja California, including areas like the one east of Guerrero Negro named Llano del Berrendo, or Pronghorn Plains. [10]

This subspecies can stand up to 35 inches tall at the shoulder and weigh in at up to 125 pounds. These animals' coloration patterns range from golden brown to tan, with white on the jaws, stomach, rump, and lower neck. The Baja California Pronghorn is often called los fantasmas del desierto which translates to, “ghosts of the desert,” because their particular coloration, in combination with their fast speeds, allow them to disappear in the desert. Furthermore, these animals' white underbellies deflect ground heat, keeping them cool. Females are smaller than males, and if horned, retain their spike-like horns for 2-5 years before shedding them. The larger males are longer horned than females, with darker faces. Males' horns are forward-pointing prongs below backward-facing hooks, and outer sheaths are shed annually. These animals are known to live roughly 9-10 years in the wild but may live longer in captivity. [11]

The Baja California pronghorn is the fastest hoofed mammal in the world and the second-fastest land mammal. They possess the ability to run at 40 - 60 miles per hour for over an hour. With 27-foot strides at their top speeds, the Baja California pronghorn has padded cloven hooves to absorb the resulting shock. When running these animals open their mouth and leave their tongue hanging to consume more air. Their windpipe can reach up to two inches in diameter, funneling air to their enlarged lungs and heart, which aid them in oxygen consumption. This unique animal’s oxygen consumption is three times greater than that of comparably sized animals. [11]

Baja California Pronghorn have remarkable eyesight and have the largest eyes of any similar-sized hoofed animal in North America. They have the ability to see for miles. Their pupils can constrict into horizontal slits, which gives them 300-degree vision, protecting them from predators. [11]

Conservation Status

[edit | edit source]Baja California pronghorn may be useful to be considered as an indicator species of the health of the larger Sonoran Desert Region of Baja California. The decline of the species suggests an untenable paradigm between human endeavor and environmental sustainability. The pronghorn, a valuable member of the food web and consumer of primary producers, being on the cusp of extinction likely indicates a major disturbance in the entire ecosystem. The inability of a previously flourishing prehistoric species to maintain its population numbers does not bode well for the broader biosphere.

Restoring pronghorn populations would be in the best interest of human beings for many reasons. Among those reasons are often posited moral claims. Many environmental schools of ethics likely result in mankind needing to take action to preserve the pronghorn. Biocentrists and zoocentrists, ecological holists and individualists, would likely all agree on the preservation of the pronghorn by essence of their position. However, the most telling argument may lie in that of the anthropocentric view of the problem. The anthropocentric view would likely be forced to admit that preservation of the pronghorn, which would require mankind to adopt a paradigm shift in relation to the environment, would certainly be the best option for mankind. This change would restore valuable ecosystem services to people and help to combat the climate crisis, ultimately serving a pragmatic role for the anthropocentric ethicist, likely without severe cost in relation to what man stands to lose.

The future for these animals remains uncertain. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists their conservation status as critically endangered. [7] Livestock fencing and cattle ranching threaten their livelihood. [11] These obstructions inhibit the animals' access to favorable habitats and their ability to conduct natural movement. Urban sprawl, human endeavor, and droughts also all threaten populations. High fawn mortality rates, exacerbated by climate change, is a major threat to the Sonoran Desert pronghorn and likely effects the Baja California pronghorn as well.[12]

In 1997, the Mexican Government, in cooperation with ENDESU (Espacios Naturales y Desarrollo Sustentable), established the Peninsular Pronghorn Recovery Project. This project, working in conjunction with zoos, such as the Los Angeles Zoo’s animal husbandry program, has grown the population of the Baja California Pronghorn to now exceed 420 animals, both captive and wild, in the areas of the El Vizcaíno Desert Biosphere Reserve and The Valle De Los Cirios Reserve. [13]

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]Baja California pronghorn have long-standing ties as a source of sustenance to people indigenous to Baja California. The animals, once widespread, were hunted with bows and arrows, eaten, and skinned to make women’s clothing. The indigenous people, the Cochimí, referred to them as ammo-gokio or ammogokió. [14] [15]

Leatherback Sea Turtle

[edit | edit source]The largest of all living turtles and is the fourth-heaviest modern reptile behind three crocodiles. It is the only living species in the genus Dermochelys and family Dermochelyidae. It can easily be differentiated from other modern sea turtles by its lack of a bony shell, hence the name. Instead, its carapace is covered by skin and oily flesh. [16]

Cultural Significance:

[edit | edit source]The Seri people, a tribe found in Mexico, find the leatherback sea turtle of significant cultural significance because it is one of their five main creators. The Seri people devote ceremonies and fiestas to the turtle when one is caught and then released back into the environment.

Ecological Trouble:

[edit | edit source]Leatherbacks have slightly fewer human-related threats than other sea turtle species. Their flesh contains too much oil and fat to be considered palatable, reducing the demand. However, human activity still endangers leatherback turtles in direct and indirect ways. Directly, a few are caught for their meat by subsistence fisheries. Nests are raided by humans in places such as Southeast Asia. In the state of Florida, there have been 603 leatherback strandings between 1980 and 2014. Almost one-quarter (23.5%) of leatherback strandings are due to vessel-strike injuries, which is the highest cause of strandings[17].

The Seri people have noticed the drastic decline in turtle populations over the years and created a conservation movement to help this. The group, made up of both youth and elders from the tribe, is called Grupo Tortuguero Comaac. They use both traditional ecological knowledge and Western technology to help manage the turtle populations and protect the turtle's natural environment.

The Seri people have noticed the drastic decline in turtle populations over the years and created a conservation movement to help this. The group, made up of both youth and elders from the tribe, is called Grupo Tortuguero Comaac. They use both traditional ecological knowledge and Western technology to help manage the turtle populations and protect the turtle's natural environment.

Vaquita

[edit | edit source]This wonderful aquatic creature named Vaquita is under the Porpoises family which is a long group of marine animals that are mammals that are classified as Phocoenidae. Also the Vaquita, is an endemic animal, that is to say relevant of its location that receives its name “ Vaquita” which in Spanish means “little cow." [18] This species appears in the Gulf of Baja California and unfortunately is in danger of extinction.

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]The Vaquita is one of the few species of the porpoise endemic which means that it exists only one place in the planet. Because of this it can bring many tourists in the area for ecotourism which is environmental tourism that sees wildlife in its habitat. But because unfortunately the Vaquita is in danger of extinction it can negatively affect the cultural aspect of the areas surrounding the Gulf of Mexico. [19]

Ecological Trouble

[edit | edit source]Unfortunately, the Vaquita is in danger to extinction. Because of this there will be fewer animals for both prey and predators many sea creatures will be affected by this in which the balance of the food chain in the Gulf of Mexico will have to change and adapt with the disappearance of this wonderful aquatic creature. Vaquitas usually eat around a dozen different type of small and medium sized fish in which will have one less predator so their numbers can grow and affect the food chain their and also other larger species such as sharks were the Vaquita’s predator in which they will have one less food source again negatively affecting the food chain. [20]

Spinytail Iguana

[edit | edit source]The Cape Spiny-tail Iguana (Ctenosaura hemilopha) is part of the Iguanidae family. Their name was given because of what they are and how they look. They help scientists by acting as a control group to the rest of the islands’ populations.

Range

[edit | edit source]These iguanas are spread out through deserts and subtropical forests in Mexico. They are found in the Sonoran Desert located in Baja California. The spiny-tail iguana lives on the peninsula of Baja California and its distribution can extend to the islands in the Sea of Cortez. They are mostly arboreal meaning that they prefer to live on trees or anything that will keep them from the ground. They can live in abandoned bird nests which can be on cacti or trees.

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]The cape spiny-tail iguana is said to have a wide distribution because the Seri people transported them everywhere, they went. The Seri people would use the cape spiny-tail iguana as a food source and to maintain the food, taking it with them was important.

Description

[edit | edit source]Cape spiny-tail iguanas are sexually dimorphic meaning that the male is larger than the female. The male can grow to be about 100 cm., while the females are about 70cm. They have a long tail that is longer than the body. When young they are a greener color with darker rings around their tail. As they grow older, they start to change to a tanner, brown coloration with darker rings around their tail. The males have larger dewlaps than the females.

Threats

[edit | edit source]One of the treats to the spiny-tail iguana is its habitat loss. With humans expanding their communities, the iguana’s habitat is being cut down. Because of this, the iguana is considered a vulnerable species.[21]

Boojum Tree

[edit | edit source]Fouqueria Coumnaris, also often referred to as a Boojum tree or Cirio tree, is a nearly endemic species of stem succulent tree found in the Baja California Peninsula. [22] These trees have a single or branched tapered primary stem. Their primary stems are armored with hundreds of horizontal secondary branches that are not succulents and are armed with spines. When moisture is available to the tree, leaves and secondary branches may grow. However, the trees are usually leafless during arid periods. In relation to moisture received during winter and spring months, the Boojum will elongate its stem. The Boojum is known to bloom in late summer and autumn, bearing clusters of white fragrant flowers or creamy yellow flowers with a honey scent. The tree is a member of the ocotillo family. The Boojum is reported to grow up to 70 feet tall, with its trunk growing up to 24cm thick. [22] [23]

Range

[edit | edit source]The Boojum tree is nearly endemic to the Baja California Peninsula. The tree grows with the help of moist, cool winds from the Pacific Ocean moderating the arid desert climate. The tree can be found in both upper and lower Baja, California. However, it is most commonly found in the subregion of Vizcaíno. Along the Gulf Coast of Sonora, a small population of Boojum exists with help from the cold waters that replicate the influence of the Pacific. [22]

Name

[edit | edit source]The plant received its English name from the Southwestern naturalist Godfrey Sykes in 1922. When Sykes encountered the foreign-looking plants, he dubbed them “boojums,” a nod to Lewis Carroll’s poem The Hunting of the Snark. The Spanish name of Cirio, meaning candle, originates from the plant's long tapered look, similar to that of candles at nearby missions. [22]

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]An indigenous group of people native to Sonora, the Seri, believe touching the Boojum tree will cause undesirable, strong winds to blow. Furthermore, botanists used to believe mainland patterns of distribution of the plant indicated that the Seri transplanted the boojum further in the interior. However, given the Seri belief about the Boojum, which they call cototaj, this belief has been called into question. [23]

Additional Information

[edit | edit source]The Boojum tree differs from its relatives in the ocotillo family by growing in the winter. Boojum trees were previously believed to only grow inches per year and reach up to 700 years old. Scientists now know that the plants can grow up to as much as 1 to 2 feet during a wet year. Additionally, repeated photography helped discover that the plants only typically live roughly a century. [23] Large individual Boojum are particularly susceptible to direct hurricane events which cause significant destruction to the Boojum population every few decades.

Notable Boojum

[edit | edit source]The tallest Boojum on record was in Montevideo Canyon near Bahai de Los Angeles. It was recorded by Robert Humphrey in the 1970s and at the time, was 81 feet tall. Hurricane Nora passed directly over the large boojum in 1997, however, the mighty tree survived. [22]

The University of Arizona recently had to remove one of its diseased Boojum trees. The tree was planted in the 1920s or 1930s after a University of Arizona sponsored Baja California trip. The specimen was a noted member of the Krutch Garden and, at 37 feet tall, one of the largest Boojum in the state. Nurserymen plan to attempt to clone the tree using its tips. This process will be documented and is an opportunity for botanists to evaluate opportunities and methods for cloning Boojums. If the precise genotype is successfully saved, it will be reintroduced into Krutch Gardens. [24]

Threats and Conservation

[edit | edit source]Boojum trees are pollinated by many different insects. A study of over 20 years yielded a wide variety of species from the same Boojum trees in both Baja California and Sonora. However, many of these species of insects have not been seen again for many years. This may be caused by a temporal niche separation. Diverse types of pollinators have been recorded every year prompted by unknown environmental circumstances in which further study is needed. [22]

Other known threats to boojum include urban sprawl, expansions of agricultural frontiers, climate change, and harvesting for ornamental wood.

The El Vizcaíno Biosphere Region was created in 1988. This protected area is 9,625 sq. miles and is the largest protected wildlife refuge in Mexico. It is home to some boojum, as well as many other protected species. The El Vizcaíno Biosphere Region borders on the Valle de los Cirios. [25]

The Valle de los Cirios, located near Guerrero Negro on the Baja California Peninsula, is the second-largest wildlife protection area in Mexico. This area was deemed a nationally-protected area in 1980 and encompasses over 9,500 sq. miles. The Valle de los Cirios contains a large population of boojum and other endemic flora and fauna. [26]

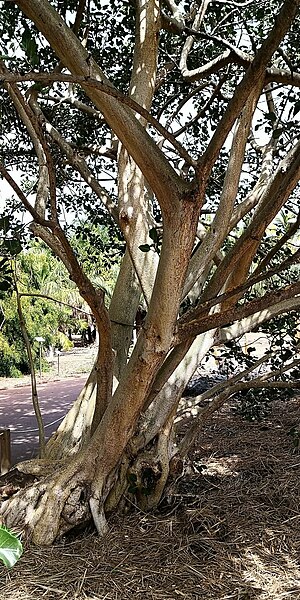

Desrt Fig Tree

[edit | edit source]Baja California has two native species of figs from the Moraceae Family: Ficus Petiolaris, which grows from the Cape Region to the Tinaja de Yubay region, in Central Baja, many of the islands, and parts of Sonora; whereas, Ficus brandegeei has a smaller range from the Cape to a little north of Loreto, only. They are both pretty similar, with the largest difference being that the Ficus Petiolaris does not display its branches and leaves with long ¨hairs¨, meanwhile, the Ficus brandegeei does. Both varieties are called Higuera ("Fig" in Spanish), Zalate or Amate ("you love you" in Spanish), or the Desert Fig in English.[27]

Ecological Significance

[edit | edit source]The Baja Ficus grows usually on cliffs or in the cracks of rocks. Trees and plants such as the Ficus, help to breakdown or weather stone, creating soil in its wake. Ficus Petiolaris, as well as three species of cacti in the Baja region (Pachycereus pringlei, Stenocerueus thurberi, and Opuntia cholla) feed on dense layers of microscopic bacteria and fungus that cover the rock surfaces. Then release valuable minerals such as potassium, zinc, magnesium, copper, iron, manganese, and phosphorus during this chemical weathering process[28]. This process provides an indispensable supply of inorganic nutrients for other plants that do grow in the soil.

In Baja, a tea made from the leaves and small branches is used as an antidote for rattlesnake bites in cattle and mules. A wash is used to treat cuts and infections. This is probably due to the facts that the milky white sap of this tree is natural latex that is toxic, a known allergen and is photosensitive. It is also shown to contain anti-inflammatory and antiseptic chemicals as well.

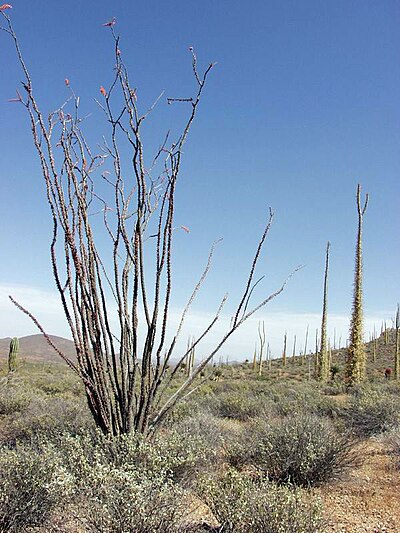

Ocotillo

[edit | edit source]This unique plant named the Ocotillo also known as a Fouquieria Splendens is a tall, greyish/greenish spiky plant from the Plantae family. [29] This plant isn't considered a true cactus even though it is covered in thorns and is ingenious to both the Sonoran Desert and the Chihuahuan Desert.

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]The Ocotillo does flower but only when it rains and when the flower dries it can be collected and used for tisanes which is an herbal tea. Also, Native American use to use to cut off the flowers when they blossomed and also cut of parts of the root and collect them for when someone in the tribe use to get cut they would apply either the root or the flower on the open cut which slowed down the bleeding. [30]

Ecological Significance

[edit | edit source]Both White-Tailed deer and Mule deer have the Ocotillo in their diet, but white-tail deer tends to eat much more Ocotillo than the Mule deer. Because the Ocotillo does flower both hummingbirds and native carpenter bees are able to get nectar from them which also helps the Ocotillo spread its pollen. [31] Also, it can provide some cover or shelter from the hot desert for smaller mammals, birds and reptiles.

Shaw's Agave

[edit | edit source]Shaw’s Agave (Agave shawii) is an agave that was called emally by the native people that used it

Range

[edit | edit source]This agave grows in the southernmost part of California and extends to Baja California. They usually grow around the coast, but nowadays, it is hard to find one of these plants in the wild.

Cultural Significance

[edit | edit source]Shaw’s Agave is an important part of the Kumeyaay people. They would consume the stalks and roots of the agave after roasting them. The leaves would be dried and beaten to take all the juices and sap out. The fibers that would be left of the leaves would be used for ropes, rabbit nets, sandals, and other things.

Description

[edit | edit source]The plant is an agave with leaves that could range from 20 cm to about 51 cm and be almost 8-20 cm wide. The leaves are arranged to form a rosette with a sharp tip on each leaf. They have a stalk in the middle that has flowers and surprisingly, the plant dies after it flowers which can take some years.

Threats

[edit | edit source]With the plant only growing on a certain area that ranges between two countries it is greatly affected by the border. These plants are rare to be seen in nature because the area they usually inhabit is being used by humans. [32]

Geology and Climate

[edit | edit source]Geology

[edit | edit source]The peninsula of Baja California is located in the northwestern part of Mexico; it covers an area of 71,777.589 km2. This peninsula extends to almost 1,300 km from north to south and is a land of steep mountain ranges and coastal valleys. Mexicali is a city just south of the US border, and the capital city of Baja California. The Gulf of California (also known as The Sea of Cortez) separates this peninsula with mainland Mexico and the maximum distance between the two is 250 km.[33] The Pacific Ocean lies on the west of Baja California. Several NNW to SSE trending mountain ranges are present on this peninsula, and Picacho del Diablo is the highest peak on the Baja California peninsula, measuring 3,096 meters (10,157 ft). It is alternately called Cerro de la Encantada, "Hill of the Enchanted", "Hill of the Bewitched". The peak is located in the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir, part of the Peninsular Ranges. Desert areas comprise about 65% of the peninsula. The largest desert in Baja California is the Vizcaíno Desert, located in the west-central part, that has been designated a protected Biosphere Reserve by the United Nations. This peninsula has a variety of types of geological environments like coastal wetlands, sandy beaches, over 100 islands mostly located along the Gulf coast.

Cape Region

[edit | edit source]A region of geologic and ecologic importance commonly referred to as the Cape Region is found stretching from La Paz to Cabo San Lucas. [34] The region’s unique geologic origins created an area uniquely adapted to being conducive to a large amount of biodiversity. Within this region lies the notable Sierra de La Laguna Biosphere Reserve.

Running through the heart of the desert is the Sierra de la Laguna Mountains. These mountains are part of a broader group of mountain ranges called the Peninsular Ranges stretching from Baja California to Southern California. [35] This region was once originally part of the Mexican mainland. However, it later was sheared off by geologic activity, becoming an island.[34] During the Miocene, ten thousand years ago, the previously isolated area reconnected with the peninsula. [36] The result of this moment was the creation of granitic mountains that run southward from the Gulf of California to the Pacific. The mountains are crossed by canyons and valleys and feature large plateaus. [36]

The geologic origins of this area led to it being one of the most biodiverse regions of Baja California. Flora and fauna evolved on this island in isolation before its collision with the desert. The region features 974 higher plant species reported with 23.2% of those being endemic species, with five endemic Geneva. [37] It also represents highly contrasting ecosystems according to UNESCO, showcasing arid zones, low deciduous forest type, matorrales evergreen oak: Quercus devia (“encino”) woods, pine-evergreen oak mix woods and oases with palms and “guerivos.” [37] These ecosystems exist within three distinct ecoregions the Sierra de la Laguna pine-oak forests, the San Lucan xeric scrub, and the Sierra de la Laguna dry forests. [35]

Mountains

[edit | edit source]“La Giganta” Mountain Range (“Sierra de la Giganta”) lies to the west, extending along the center of the state of Baja California Sur, parallel to the gulf coast[38]. The geology and topography of the Loreto region, extending from Bahía Concepción to Agua Verde, is a coastal belt consisting "mainly of a narrow belt of ridges, valleys, and pediments adjacent to the escarpment, low- to moderate-elevation ranges transverse to the coast, and narrow coastal plains”.

Volcanos

[edit | edit source]Volcán Coronado is a small stratovolcano at the northern tip of Coronado Island, 3 km off the eastern coast of Baja California in the Canal de los Ballenas. The roughly 440-m-high volcano forms a 2-km-wide peninsula at the northern end of the elongated NNW-SSE-trending island and contains a 300 x 160 m wide crater. The age of the most recent eruptive activity from Volcán Coronado is not known, although fumarolic activity was reported in September 1539 (Medina et al., 1989).[39]

The Cultural Use of Minerals

[edit | edit source]Baja California is home to a total of 161 operating mines in the whole Mexican state. A total of 19 different minerals are being mined which are Gold, Tungsten, Copper, Iron, Silver, Phosphorus-Phosphates, Sulfur, Manganese, Lead, Aluminum, Barium-Barite, Graphite, Silica, Zinc, Zirconium, Titanium, Titanium Metal, Molybdenum and Chromium. The mines are spread out through the state of Baja California and are broken into 5 different provinces which is placed depending on its location and what are mined. In the first province deposits of mesothermal sulfates of iron, copper and gold are being mined. The second province corresponds to the gold veins distributed along the whole state. The third province corresponds to deposits of tungsten. The fourth province corresponds to the deposits of manganese sulfites, barite, lead, zinc and silver. The fifth province involves the gold pleasure deposits. Some of the cities in Baja California that have these mines are Tijuana (which has 23 operating mines), Ensenada (which has 13 operating mines) and Mexicali (which has 4 operating mines). More mines are located in other cities and towns throughout the Baja California region. [41]

Climate

[edit | edit source]The Gulf's climate is hot and humid, with abundant sunshine (desert with some rainfall in summer). The median temperature is 24.4 °C (76 °F). The temperatures are hot from June through October. These summer days have highs around 34 °C (93 °F) and high humidity. Such as the city of Loeto, which according to the National Meteorological Service, Loreto's highest official temperature reading of 44.2 °C (112 °F) was recorded on July 2, 2006; the lowest temperature ever recorded was 0.0 °C (32 °F) on December 15, 1987[42]. In the spring season, the temperatures are moderate and temperate. Autumn and winter months are usually windy. The city is built on relatively flat land with an average elevation is 10 meters (33 ft) above sea level. [43]

Land and Water Use

[edit | edit source]Land Use

[edit | edit source]For land usage, unfortunately, there is a lot of trash that is illegally dumped throughout the desert and in the ocean but the trash that is collected, each city in Baja California gathers it and disposes it to its closest landfill in which each large city has their own in their outskirts and the smaller towns around it uses them as well. Landfills are located in San Luis Rio Colorado, Mexicali, Tijuana, Ensenada, San Quintin, Rosarito, Santa Rosalia, Loreto and La Paz. [44] Sewage waste is also disposed of in landfills alongside solid waste.

Mining

[edit | edit source]Mining is one of the primary land uses in the Baja California Region of the Sonoran Desert. It is also one of the most significant challenges to sustainability in the area. Mining sites are widespread throughout the Baja California Peninsula. Gypsum ore is mined on the San Marcos Islands.[45] Copper and manganese mining is being revived in Santa Rosalia. [46] Phosphorous mining is present in San Juan De La Costa. [47] Gold and silver were mined in the areas of El Trunfio and Bahia De Los Angeles. [48] [49] Outside the town of Guerrero Negro, near the edge of Lago Ojo de Liebrea, one of the region's most massive mining expeditions exists, a salt mine producing seven million tons of salt yearly. [50]

A notable example of environmental justice was the recall of permits allowing construction of the proposed Los Cardones Mine. The proposed site, owned by the Mexican company Invecture Group and closely affiliated with Vancouver-based Frontera Mining Corporation, consisted of 13,000 hectares of land 65km southeast of the city of La Paz in Baja California and fell within the Sierra de La Laguna Biosphere Reserve. [51] Risks anticipated with the site included contaminated ground and drinking water, cyanide pollution and high levels of dust laced with arsenic and heavy metals. [52]

Local and international protests drew researchers and government officials into the dispute. A team of researchers from N-Gen, the Mexican Commission for Natural Protected Areas (CONANP), the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, UC MEXUS, multiple participating academic institutions, local NGOs, and local community members conducted research into the issue concluding:

Our international team of 29 scientists from 19 institutions conducted a biodiversity survey inside the Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve in Baja California Sur, Mexico. This eight-day expedition was undertaken at the request of, and in collaboration with CONANP to document the diversity encountered on ca. 1,235 acres of land currently petitioned for use as the open pit gold mine project Los Cardones. From December 4th to 11th of 2015 the participating scientists documented the presence of 877 species, including 381 plants, 29 mammals, 77 birds, 366 insects, and 24 reptiles and amphibians. The true diversity of the region is expected to be double that documented in the week-long excursion. The majority of the diversity was found associated with the La Junta riparian system at the core of the proposed mine site. Twenty-nine species, protected under Mexican law due to their inclusion on the endangered species list (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010), were discovered inside the project footprint, as well as 107 species endemic to the Cape Region. The biodiversity found in and around Arroyo La Junta and its tributaries forms the base of a complex food-web. Based on the high levels of diversity and endemism, especially the multitude of life forms associated with aquatic habitats, the findings of this initial survey support the prior designation by Mexican and international bodies of this region as a protected area. [53]

This attention, in conjunction with widespread protests coordinated by local communities and environmental justice groups, spurred governmental action and in 2017 SEMARNAT, Mexico’s central environmental authority, revoked the companies permits to mine. However, estimated reserves of 1.2 million ounces of gold are believed to exist there, leading to speculation mining companies may revise their strategies and renew attacks. [54]

Though the Los Cardones mine was never started, mining continues to operate and expand throughout the Sonoran Desert and broader regions. In any attempt to create a model for sustainable use of water and land in the Baja California portion of the Sonoran Desert, equal attention and stewardship should be given to the desert areas surrounding the Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve. The Los Cardones project may serve as an example of successful conservation through cohesion and coordination between environmentally conscious citizens, researchers, organizations, and governmental officials.

Water Use

[edit | edit source]The Gulf of California is also known as Sea of Cortez in Mexico and was named after the 16th-century Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés. The Mexican government changed the official name to the Golfo de California (Gulf of California) in the early 20th century, although both names are in vogue and are interchangeably used on maps [55]. This gulf is over 1000 km long that extends from the mouth of the Colorado River in the north to the cape at San Lucas in the south[56]. The Colorado River Delta was once the most important wetland of Western North America now has become almost like a desert due to this river being dammed within the USA. The sea is shallow in the north because sediment brought by the Colorado River forms a huge delta that extends from land into the sea. This gulf south of La Paz becomes more or less like an ocean, with deep trenches, canyons, and tall seamounts, and meets the Pacific Ocean further south at the southernmost tip of the Baja Peninsula known as Finisterra or the Land’s End.[57]

For water usage the water is gathered from the Colorado River in Mexicali Baja California and with a canal system it goes through La Rumorosa which goes to into a reservoir named “El Carrizo” in which Tecate, Rosarito and Tijuana Baja California. In the south most of the water is collected by rainfall in the mountains named “Sierra de las Trincheras” and “El Novillo” in which water is distributed to La Paz and its surrounding towns. [58]

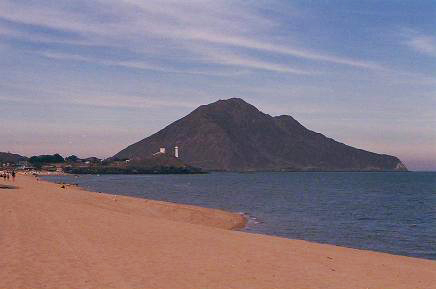

Opportunites and Threats

[edit | edit source]Many opportunities are found in Baja California because it is in the middle of both the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California. Because of this tourism is in every city that is in the shore to either of the Pacific Ocean or the Gulf of California. For example, San Felipe is in the shore of the Gulf of California and because of this many people from both the U.S and other parts of Mexico go there to enjoy the beach. [60] Also because of the tourism the beaches bring San Felipe they also host an off-road racing event named San Felipe 250 which happens yearly bringing more people to this city.

The threats from what the Baja California Peninsula and the Gulf of California suffers from are all done by humans. The principal threats are livestock ranching, salt extraction, and hunting. With ranching many acres of space are taken away in which affected both populations of mule deer and bighorn sheep significantly. With hunting because so much deer type animals are being hunted it has affected the population of Pumas in the area due to they no longer have their main source of food available as much as they were having. And with the salt extraction from the see this has negatively affected the breeding and migration of gray whales. [61]

Climate Change

[edit | edit source]Climate change looms as the largest ecological threat to the Baja California subregion and the entire Sonoran Desert. Unchecked, the effects of climate change in the Sonoran Desert will be far-reaching and widespread throughout all biomes and ecosystems. The Sonoran Desert already finds itself in a drought with at least a 25 to 40% drop in precipitation over the last 50 years. [62] The region has been identified as being within a projected “global hot spot” resulting from climate change, with models demonstrating warming of 5.4-10.8 degrees Fahrenheit. [63]

Increased temperatures place strains on entire ecosystems by undermining food webs. Warming temperatures, among many other factors, will increase evapotranspiration rates, stressing primary producers, and the resulting food webs. Slow-moving species such as desert tortoises will have much harder times reacting to the unpredictable weather patterns produced by climate change. [64] Furthermore, species capable of more rapid reaction and migration may attempt to move out of designated protected wildlife areas, such as the Valle de los Cirios area, only to have their movement blocked by human habitat fragmentation.

Opportunities to address climate change exist at every moment of every person’s day on a global scale. From choosing a profession that champions global climate change causes or conducts research to a persons simple daily choices, there is a way for everyone to get involved. A plethora of information is widely available for making more sustainable choices. Other ways to help address climate change are to research and donate to the most effective organizations battling climate change. Practicing responsible civics by researching and voting for environmentally friendly legislation and candidates and starting grassroots environmental movements or joining current movements are all ways of addressing climate change.

Invasive Species

[edit | edit source]Sahara mustard weed, a large, hardy fast-growing winter annual, along with a with similar invasive grass, Buffelgrass, threaten many of the endemic flora of Baja California and the Sonoran Desert. Sahara mustard started as a localized population before beginning a massive range expansion. The weed is particularly effective at challenging native cacti and perennial shrubs for resources such as light and soil moisture. Furthermore, the weed possesses the capacity to smother native herbaceous plants. [65]

First recorded in California’s Coachella Valley in 1927, by the 1970s the plant was widespread across the Sonoran Desert and Baja California. Sahara mustard mainly kept to disturbed soil and sandy areas until in the 1990s, when it began invading undisturbed desert. In the twenty-first century, the weed again adapted and began invading the steep desert slopes and rocky soils of the Sonoran. It is now known to cause acres of impenetrable thickets in some places, completely excluding any other annuals. [65]

Currently, research is being conducted on the best ways to combat aggressive invasive species such as Sahara mustard weed. The most effective method to date is hand weeding. [66] Though this method is not considered a tenable long-term solution, it has been shown to be useful while research is being developed. The Bureau of Land Management conducts hand weedings, in which they may be looking for local volunteers. [66] Contacting your local BLM office may be one of the best ways to help fight such invasive species. Furthermore, the U.S. Forest Service recommends detecting, reporting, and mapping known infestations. [67]

Endangered Species

[edit | edit source]Antilocapra americana peninsularis, also known as the Baja California pronghorn, is a subspecies of pronghorn endemic to the Baja California Peninsula. The Baja California pronghorn is a critically endangered subspecies according to the IUCN with only an estimated 200 animals remaining in the wild. [7]

Combatting climate change may be one of the best ways to help save the pronghorn. High mortality rates, especially during droughts have contributed to the decline of this species. Currently, CONANP (Mexico’s National Commission of Protected Natural Areas) is working with American organizations such as the L.A. Zoo to stabilize the pronghorn through the Peninsular Pronghorn Recovery Program in the El Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve. Consider donating to or contacting these organizations to ask how you can help these animals. Finally, people can raise awareness about the Baja California pronghorn.

Fishing

[edit | edit source]Fishing can be seen as both an opportunity and a threat if the proper precautions aren't taken. The country of Mexico has taken great measures to make sure laws are placed so that overfishing doesn't occur and disrupt marine life. Guaymas is one of the prime examples of how vital fishing can be to an economy. Guaymense fishing occupies 11,800 people in the catch and another 325 are engaged in aquaculture. It contributes 70% of the total state fisheries production, with the main species caught, sardine, shrimp, and squid [68]. It has 175 kilometers of coastline where important bays such as Guaymas, Lobos, San Carlos (Mexico), and the Herradura are formed. The municipality has more than 83% of the docks operating in the State. The fleet consists of 359 shrimp vessels, 32 sardineras, 3 escameras, and 910 smaller vessels, for a total of 1,304. 55% of catches are traded in the State and the rest, i.e. 45% has as its final destination the domestic market and the foreign market [69], to the latter, is mainly sent shrimp that has a high price in the international market, which makes guaymense fishing very dependent on the conditions of this market. The population of fishermen in coastal communities has its ancestry by 80% in the same region where the community is located; the rest comes from other localities of the state and about 5 percent from other states, particularly Sinaloa and Nayarit.

Tourism

[edit | edit source]Due to the cities' of the Gulf having some incredible beaches and marine life, they have naturally become popular tourist destinations. Tourism is one of the highest sources of income for many of the coastal cities. One example is the city of Loreto. The city is a tourist resort, catering mostly to American travelers, with daily flights from California to Loreto International Airport[70]. Many American tourists enjoy fishing in "pangas" for "dorado" (Mahi-mahi or Dolphin Fish). Local restaurants willingly prepare the daily catch of the tourists. Loreto has a museum that coexists alongside the historic, but still active, parish. Loreto has active sister city relationships with the California cities of Hermosa Beach, Cerritos, and Ventura.

Urban Sprawl

[edit | edit source]Urban sprawl is a current threat to the Sonoran Desert portion of Baja California. Cabo San Lucas is a major tourist destination for Baja California. However, developers now have sourced colonial Loreto as a potential location for a tourist and vacation destination. These developing tourism destinations threaten to bring urban sprawl to the lower half of Baja California, increasing the probability of land conversion and habitat fragmentation, affecting endemic species.

Urban sprawl may have secondary detrimental environmental effects. Baja California sources the majority of its energy from power plants, such as those in Rosarito and Ensenada. [71] These power plants are massive contributors to man-made climate change. Increases in tourism and resulting urban sprawl will increase demand for energy from these pants, which run off destructive natural gasses supplied by the United States. [72]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b North, Arthur W. "The Native Tribes of Lower California." American Anthropologist 10.2 (1908): 236-50. Web. 14 May 2020.

- ↑ Fujita, Harumi. "Prehistoric Occupation of Espíritu Santo Island, Baja California Sur, Mexico: Update and Synthesis." Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 30.1 (2010): 17-33. Web. 14 May 2020.>

- ↑ a b c Beer, N., S. Gonzalez, D. Huddart, A. Rosales-Lopez, and A. Lamb. "The Palaeodiet of the Pericue Indians of the Cape Region of Baja California Sur, Mexico." AGU Spring Meeting Abstracts 2007 (2008): n. pag. SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System, 2008. Web.

- ↑ "Cochimí." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 10 May 2020. Web.

- ↑ "Guaycura People." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 09 May 2020. Web.

- ↑ Macfarlan, Shane J., and Celeste N. Henrickson. "Inferring Relationships Between Indigenous Baja California Sur and Seri/Comcáac Populations Through Cultural Traits." Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 30.1 (2010): 51-67. Web. 14 May 2020.

- ↑ a b c IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group. 2016. Antilocapra americana (errata version published in 2017). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T1677A115056938. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T1677A50181848.en. Downloaded on 05 May 2020.

- ↑ Brown, David & Cancino, Jorge & Clark, Kevin & Smith, Myrna & Yoakum, Jim. (2009). An Annotated Bibliography of References to Historical Distributions of Pronghorn in Southern and Baja California. Bulletin, Southern California Academy of Sciences. 105. 1-16. 10.3160/0038-3872(2006)105[1:AABORT]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ “Pronghorn, Peninsular.” Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens, www.lazoo.org/animals/mammals/peninsular-pronghorn/#1477087121998-c3c62c95-de4e142a-9e99.

- ↑ Phillips, Steven John, Patricia Wentworth Comus, and Mark A. Dimmitt. "Sonoran Desert Mammals." A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. Berkeley: U of California, 2015. 422. Print.

- ↑ a b c d "Pronghorn, Peninsular." Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens. N.p., n.d. Web.

- ↑ drought, & recruitment, fawn & mortality, & predation,. (2009). Adult and fawn mortality of Sonoran pronghorn. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 43-50. 10.2193/0091-7648(2005)33[43:AAFMOS]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Tayles, Melodi. Peninsular Pronghorn. San Diego: San Diego Zoo Global, 2019. PDF.

- ↑ "Pronghorn, Peninsular.” Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens, www.lazoo.org/animals/mammals/peninsular-pronghorn/#1477087121998-c3c62c95-de4e142a-9e99.

- ↑ “Mammals.” Bajacalifology.org - Ethnobiology : Mammals, www.sandiegoarchaeology.org/Laylander/Baja/bio.mammals.htm.

- ↑ Sartore, Joel. “Leatherback Sea Turtle.” National Geographic, 24 Sept. 2018, www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/reptiles/l/leatherback-sea-turtle/.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leatherback_sea_turtle

- ↑ The Marine Mammal Center. (2019, January 11). Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.marinemammalcenter.org/science/Working-with-Endangered-Species/vaquita.html

- ↑ Vaquita | Species | WWF. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/vaquita

- ↑ Vaquita | Species | WWF. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/vaquita

- ↑ [1], Cape spiny-tailed iguana. (2018, December 9). Retrieved from https://www.mexican-fish.com/cape-spiny-tailed-iguana/

- ↑ a b c d e f Phillips, Steven John, Patricia Wentworth Comus, and Mark A. Dimmitt. "Flowering Plants of the Sonoran Desert." A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. Berkeley: U of California, 2015. 222 - 224 Print.

- ↑ a b c "Fouquieria Columnaris." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Nov. 2019. Web.

- ↑ UA News Services. "Ailing Historic Boojum Tree to Be Removed." UANews. University of Arizona, 21 Mar. 2005. Web.

- ↑ "El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 25 Feb. 2020. Web.

- ↑ "Valle De Los Cirios." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 26 Apr. 2020. Web.

- ↑ Miller, Cheryl. “Desert Fig.” Baja Realty and Investments, www.forsaleinbaja.com/desert-fig.html.

- ↑ Miller, Cheryl. “Desert Fig.” Baja Realty and Investments, www.forsaleinbaja.com/desert-fig.html.

- ↑ LADY BIRD JOHNSON WILDFLOWER CENTER. (n.d.). Fouquieria splendens. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=fosp2

- ↑ Munsey, S. (2019, May 14). 10 ocotillo facts that will make you love this desert plant even more. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://thisistucson.com/tucsonlife/ocotillo-facts-that-will-make-you-love-this-desert-plant/article_27f6a926-314c-11e8-abf2-1b0322c94205.html

- ↑ Munsey, S. (2019, May 14). 10 ocotillo facts that will make you love this desert plant even more. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://thisistucson.com/tucsonlife/ocotillo-facts-that-will-make-you-love-this-desert-plant/article_27f6a926-314c-11e8-abf2-1b0322c94205.html

- ↑ [2], Summary of Shaw's agave and its traditional use. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.sandiego.edu/cas/biology/kumeyaay-garden/plants/shaws-agave.php

- ↑ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Baja California.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 7 May 2019, www.britannica.com/place/Baja-California-peninsula-Mexico.

- ↑ a b Eisen, Gustav. “Explorations in the Cape Region of Baja California.” Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York, vol. 29, no. 3, 1897, pp. 271–280. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/197262.

- ↑ a b "Peninsular Ranges." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 22 Apr. 2020. Web.

- ↑ a b Valero, Alejandra, Jan Schipper, and Tom Allnutt. "Sierra De La Laguna Dry Forests." WWF. World Wildlife Fund, n.d. Web.

- ↑ a b "Biosphere Reserve Information - Mexico - SIERRA LA LAGUNA." UNESCO - MAB Biosphere Reserves Directory. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2011. Web.

- ↑ “The Canyons of the Sierra De La Giganta.” A Life Times Two, 10 May 2012, kommoss.wordpress.com/2008/01/16/295/.

- ↑ Medina F, Suarez F, Espindola J M, 1989. Historic and Holocene volcanic centers in NW Mexico. Bull Volc Eruptions, 26: 91-93.

- ↑ File:Sulphur-43107.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). In Wikimedia. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sulphur-43107.jpg

- ↑ Wilson, I. F. W. (n.d.). Geology and Mineral Deposits of the Boleo Copper District Baja California, Mexico. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0273/report.pdf

- ↑ http://vivabaja.mx/about-loreto

- ↑ https://www.wunderground.com/weatherstation/WXDailyHistory.asp?ID=ISONHERM2

- ↑ GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO DE BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR. (n.d.). PROGRAMA ESTATAL PARA LA PREVENCIÓN Y GESTIÓN INTEGRAL DE RESIDUOS PARA EL ESTADO DE BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/187449/Baja_California_Sur.pdf

- ↑ "San Marcos Island." USGS - Science for a Changing World. N.p., n.d. Web. https://mrdata.usgs.gov/mrds/show-mrds.php?dep_id=10048952.

- ↑ "Boleo Project - Mining Technology: Mining News and Views Updated Daily." Mining Technology | Mining News and Views Updated Daily. N.p., 2020. Web. https://www.mining-technology.com/projects/boleoproject/.

- ↑ "San Juan De La Costa." USGS - Science for a Changing World. N.p., n.d. Web. https://mrdata.usgs.gov/mrds/show-mrds.php?dep_id=10048963.

- ↑ "El Triunfo, Baja California Sur." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 01 Oct. 2019. Web.

- ↑ "Flores Mine, Bahia De Los Angeles, Ensenada Municipality, Baja California, Mexico." Flores Mine, Bahia De Los Angeles, Ensenada Municipality, Baja California, Mexico. N.p., n.d. Web. https://www.mindat.org/loc-11190.html.

- ↑ “El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve, Mexico.” NASA, NASA, earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/77499/el-vizcaino-biosphere-reserve-mexico.

- ↑ "Baja California Sur." Earthworks. N.p., 04 Mar. 2019. Web. https://earthworks.org/stories/baja_california_sur/.

- ↑ "Baja California Sur." Earthworks. N.p., 04 Mar. 2019. Web. https://earthworks.org/stories/baja_california_sur/.

- ↑ Vanderplank S, BT Wilder, E Ezcurra. 2016. Arroyo la Junta: Una joya de biodiversidad en la Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra La Laguna / A biodiversity jewel in the Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve. Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers, and UC MEXUS. 159 pg.

- ↑ "AMLO Says No to Controversial Mining Project in Baja California Sur." Mexico News Daily. N.p., 04 Mar. 2019. Web.

- ↑ History.com Editors. “Hernan Cortes.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 9 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/topics/exploration/hernan-cortes.

- ↑ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Cape San Lucas.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 12 Aug. 2008, www.britannica.com/place/Cape-San-Lucas.

- ↑ Kumar, Arun. (2013). Geological history of the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico and the fascinating world of its endemic plants.. Earth Science India (Popular issue). VI. 1-27.

- ↑ Garcia, L. A. G. (2016, November 30). La ruta del agua (la poca que queda) en Baja California. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.sandiegored.com/es/noticias/133217/La-ruta-del-agua-la-poca-que-queda-en-Baja-California

- ↑ File:Presa Plutarco Elias Calles “El Novillo”.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). In Wikimedia. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Presa_Plutarco_Elias_Calles_%22El_Novillo%22.jpg

- ↑ Experience San Felipe. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.mexperience.com/travel/beaches/san-felipe/

- ↑ WWF. (n.d.). Southern North America: Baja California Peninsula in Mexico | Ecoregions | WWF. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na1301

- ↑ Phillips, Steven John, Patricia Wentworth Comus, and Mark A. Dimmitt. "Desert Storms." A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. Berkeley: U of California, 2015. 49. Print.

- ↑ Phillips, Steven John, Patricia Wentworth Comus, and Mark A. Dimmitt. "Desert Storms." A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. Berkeley: U of California, 2015. 50. Print.

- ↑ Phillips, Steven John, Patricia Wentworth Comus, and Mark A. Dimmitt. "Conservation Issues in the Sonoran Desert." A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. Berkeley: U of California, 2015. 117. Print.

- ↑ a b Phillips, Steven John, Patricia Wentworth Comus, and Mark A. Dimmitt. "Conservation Issues in the Sonoran Desert." A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. Berkeley: U of California, 2015. 114. Print.

- ↑ a b "Sahara Mustard." Center for Invasive Species Research. N.p., 18 Jan. 2020. Web. https://cisr.ucr.edu/invasive-species/sahara-mustard.

- ↑ Field Guide for Managing Sahara Mustard in the Southwest. Southwestern Region: USDA - United States Department of Agriculture, Feb. 2005. PDF.

- ↑ Williams, J.H. (August 1996). Baja Boaters Guide II: Sea of Cortez. H.J. Williams Publications. pp. 202–4, 209–211. ISBN 0-9616843-8-0.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guaymas

- ↑ https://ladamianainn.com/loreto-bcs-mexico/

- ↑ "The Opening of Baja California III Ratifies Our Leadership as the Main Private Energy Producer in Mexico." Iberdrola. Iberdrola Corporativa, n.d. Web.

- ↑ Sweedler, Alan. "Climate Change and Energy in the California-Baja California Border Region." (n.d.): n. pag. EPA.gov. Sept. 2015. Web.