Survey of Communication Study/Chapter 13 - Gender Communication

Gender Communication

[edit | edit source]Chapter Objectives: |

When was the last time you heard someone say, “like a girl” with a positive overtone? We have been taught that performing "like a girl" is the equivalent of performing poorly. The company always decided to examine the phrase "like a girl" and how children of different ages would respond! The results were not what you would expect! The phrase “Like a Girl” might have originally held a negative connotation but this idiom is due for a revolution! The way we refer to "girls" communicates gender expectations.

We use a variety of channels of communication (language, books, tv, clothing, etc.) to teach children what it means to be a "girl" and a "boy". We often limit these identities to separate categories that we are not supposed to mix. We are taught that men are supposed to be more athletic than women and play in different leagues. In almost every professional sport, such as football, baseball, and basketball the men’s league is seen as more competitive and more popular.

So what happens when a girl is able to throw a 70 mile per hour fastball and win The World Series for her team? Mo’ne Davis was the first girl to pitch a shutout in the Little League World Series in August 2014, showing everyone what it means to throw like a girl. Davis is being recognized because of her rare talent, but also because of her gender (Wallace). With Davis as a role model, we may see many more examples of transformations of traditional gender roles. For more information on Mo’ne, check out this link.

This example highlights one of the key characteristics of gender—-that it is fluid. Gender roles of a given culture are always changing.

Like in sports, people of all genders are taking on new roles in all different ways. This picture depicts females on the field during a competitive game of lacrosse at Humboldt State University in Arcata, California, a sport traditionally played by men.

In this chapter, we will look at the ways in which gender has been constructed in American life, and ways in which we communicate about the ideas of gender.

The Study of Gender Communication

[edit | edit source]Gender communication is a specialization of the Communication field that focuses on the ways we, as gendered beings, communicate. Gender research might look at roles for people of different genders in academia, sports, media, or politics. Research in this area, for example, could examine the similarities and differences in the conversations that take place in the comment section of a Youtube video created by Bethany Mota verses one created by Philip DeFranco. Researchers could also look at how people of different genders have been represented throughout history. Gender communication is also a field that strives to change the way we talk about people, in order to make a more empathetic and safe space for our entire community. The word “queer,” for example, used to be a slur for people who were homosexual. Now we see the LGBTQIA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual) community has reclaimed the word queer to mean any person who is not straight. It is now a self-proclamation and one that can be empowering for many people.

In this chapter, we want to make a distinction between sex and gender before providing an overview of this specialization’s areas of research, main theories and theorists, and highlights from research findings about feminine and masculine communication styles. While we are taking a communication lens to the study of gender, we need to acknowledge the contributions made by other academic disciplines such as women’s studies, linguistics, and psychology (Stephen, 2000).

As with other specializations in communication, definitions of gender abound (Gilbert; Howard & Hollander; Lorber; Vannoy). Ivy and Backlund define gender communication as, “communication about and between men and women” (4). Central to this definition are the terms about and between, and men and women. About addresses the attention this specialization pays to how the sexes are “discussed, referred to, or depicted, both verbally and nonverbally.” Between addresses how members of each sex communicate interpersonally with others of the same, as well as the opposite, sex (Ivy & Backlund 4). We find this problematic because it limits the discussion about gender to only men and women. For our purposes, we will be adapting the Ivy and Backlund definition and instead using the definition of gender communication: communication about and between people of all genders. This new definition is more inclusive of the large number of gender identities that are present in our communities, such as gender queer, transgender, and a-gender. We will discuss and define some of these identities later in the chapter. For a more in-depth exploration of these identities, check out this article from the Huffington Post.

Wendy Martyna the author of “What Does “He” Mean?” discusses how the pronoun “He” has been used to reference men, as well as people in general. Although men are not the only people on Earth, the generic terms widely used to describe people are often, “Men” or “He.” Such as, “All 'men' are created equal.” Martyna explains that the original argument for this usage was clarity. She set out to prove this argument as false by asking college students to fill in blanks with proper pronouns like, “When an engineer makes an error in calculation ____” or, “When a babysitter accepts an assignment ___.” Her thinking was that if “He” is truly generic than it would make sense that those surveyed would use, “he” in every blank. What followed was as expected, “While a hypothetical police officer was ‘he,’ a hypothetical babysitter was ‘she.’"

In American society, we often use the gendered terms "women" and "men" instead of "male" and "female." What’s the difference between these two sets of terms? One pair refers to the biological categories of male and female. The other pair, "men" and "women," refers to what are now generally regarded as socially constructed concepts that convey the cultural ideals or values of masculinity and femininity. For our purposes, gender is, “the social construction of masculinity or femininity as it aligns with designated sex at birth in a specific culture and time period. Gender identity claims individuality that may or may not be expressed outwardly, and may or may not correspond to one’s sexual anatomy” (Pettitt). This definition is important because it discusses the separation between sex and gender as well as the idea that gender is socially constructed.

This basic difference is important, but most important is that you know that one of these two sets of terms has a fixed meaning and the other set maintains a fluid or dynamic meaning. Because they refer to biological distinctions, the terms male and female are essentially fixed. That is, their meanings are generally unchanging (as concepts if not in reality, since we do live in an age when it’s medically possible to change sexes). Conversely, because they are social constructions, the meanings of the gendered terms masculine and feminine are dynamic or fluid. Why? Because their meanings are open to interpretation: Different people give them different meanings. Sometimes, even the same person might interpret these terms differently over time. A teenage girl, for example, may portray her femininity by wearing make-up. Eventually, she may decide to forego this traditional display of femininity because her sense of herself as a woman may no longer need the validation that a socially prescribed behavior, such as wearing make-up, provides. We use the terms "fluid" and "dynamic" to describe the social construction of gender because they will change based on the time, place, and culture in which a person lives. Did you know that high heels were first invented for men to make them look taller? These days, if a man wears high heels, he would be described as “feminine.” This is an example of how our ideas of gender can change over time.

The Interplay of Sex and Gender

[edit | edit source]A quick review of some biological basics will lay a good foundation for a more detailed discussion of the interplay between sex and gender in communication studies.

Sex

[edit | edit source]As you may recall from a biology or health class, a fetus’s sex is determined at conception by the chromosomal composition of the fertilized egg. The most common chromosome patterns are XX (female) and XY (male). After about seven weeks of gestation, a fetus begins to receive the hormones that cause sex organs to develop. Fetuses with a Y chromosome receive androgens that produce male sex organs (prostate) and external genitalia (penis and testes). Fetuses without androgens develop female sex organs (ovaries and uterus) and external genitalia (clitoris and vagina). In cases where hormones are not produced along the two most common patterns, a fetus may develop biological characteristics of each sex. These people are considered intersexuals.

Case In Point |

As you know, hormones continue to affect us after birth—throughout our entire lives, in fact. Hormones control when and how much women menstruate, how much body and facial hair we grow, and the amount of muscle mass we are capable of developing. Although the influence of hormones on our development and existence is very real, there is no strong, conclusive evidence that they alone determine gender behavior. The degree to which personality is influenced by the interplay of biological, cultural, and social factors is one of the primary focal points of gender studies.

|

Gender

[edit | edit source]Compared with sex, which biology establishes, gender doesn’t have such a clear source of influence. Gender is socially constructed because it refers to what it means to be a woman (feminine) or a man (masculine). The fact that females can be masculine or perform masculinity, and males can perform femininity proves that gender is not tied to sex. Traditionally, masculine and feminine characteristics have been taught as complete opposites when in reality there are many similarities. Gender has previously been thought of as a spectrum, as a line; this implies the drastic separation of genders. A better way to think about gender is a circle, where all genders can exist in relation to each other.

The more archaic term for this expression of gender is known as androgyny, the term we use to identify gendered behavior that lies between feminine and masculine—-the look of indeterminate gender. Gender can be seen as existing in a fluid circle because feminine males and masculine females are not only possible, but common, and the varying degrees of masculinity and femininity we see (and embody ourselves) are often separate from sexual orientation or preference. The circle chart illustrates how all genders exist on a sort of plane. They are not arranged in a straight line, with female on one end, and male on the other. There are no set borders to any one gender, and there is open space for people to define themselves however they decide.

The Social Construction of Gender

[edit | edit source]In this section, we discuss how gender is dynamic, social, symbolic, and cultural. Gender is dynamic, not just because it exists on a plane, but because its meanings change over time within different cultural contexts. In 1907, for example, women in the United States did not have the legal right to vote, let alone the option of holding public office. Although a few worked outside the home, middle class white women were expected to marry and raise children. A woman who worked, did not marry, and had no children was considered unusual, if not an outright failure. Now, of course, women have the right to vote and are considered an important voting block. There are many women who are members of local and state governing bodies as well as the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, even though they aren’t representative in government of their 51 percent of the population. Similarly, men were also prescribed to fill a role by society one hundred years ago: wage earner. Men were discouraged from being too involved in the raising of children, let alone being stay-at-home dads. Increasingly, men are accepted as suitable child-care providers and have the option to stay home and raise children.

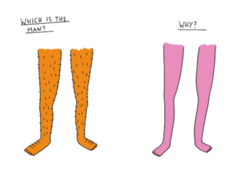

As a social construct, gender is learned, symbolic, and dynamic. We say that gender is learned because we are not born knowing how to act masculine or feminine, as a man or a woman, or even as a boy or a girl. Just as we rely on others to teach us basic social conventions, we also rely on others to teach us how to look and act like our gender. Whether that process of learning begins with our being dressed in clothes traditionally associated with our sex (blue for males and pink for females), or being discouraged from playing with a toy not associated with our sex (dolls for boys, guns for girls), the learning of our genders begins at some point. Once it’s begun (usually within our families), society reinforces the gender behaviors we learn. Despite some parents’ best efforts to not impose gender expectations on their children, we all know what is expected of our individual gender.

Although there is an endless supply of forces imposing influence on our gender development, our parents are generally believed to be the strongest. They provide the earliest foundation upon which gender socialization is created. A child's gender development is thought to be affected by their parents in four ways. First, parents provide their children with gender-stereotyped day to day activities, toys, or chores, all of which shape the gendered attributes of the child. Second, interactions between parents and children tend to differ between daughters and sons. Generally, a boy will receive more engaging, hands-on styles of play while a girl will be approached in a more conversational manner. Third, parents provide the first impression of what gender roles are for their child. For example, if a child grows up in a setting where their father is always doing yard work and playing sports while their mother is always cooking and cleaning, they will think these are the standard gender roles of men and women. Finally, verbal messages conveyed directly to the child support or discourage certain gender ideals. When parents say things like “boys don’t cry,” or “girls don’t hit,” they are reaffirming stereotypical gendered roles within our society. Furthermore, parents can verbally influence their child's gender socialization without speaking to them directly, in instances such as criticizing the behavior of another person.

Gender is symbolic because it is learned and expressed through language and behavior. Language is central to the way we learn and performe gender through communicative acts because language is social and symbolic. Remember what we learned in chapter two, that language is symbolic because the word “man” isn’t a real man. It is a symbol that identifies the physical entity that is a human male. So, when a mother says to her children, “Be a good girl and help me bake cookies,” or “Boys don’t cry” children are learning through symbols (language) how to “be” their gender. The toys we are given, the colors our rooms are painted, and the after-school activities in which we are encouraged to participate are all symbolic ways we internalize, and ultimately act out, our gender identity.

Case In Point |

Finally, gender communication is cultural. Meanings for masculinity and femininity, and ways of communicating those identities, are largely determined by culture. A culture is made up of belief systems, values, and behaviors that support a particular ideology or social system. How we communicate our gender is influenced by the values and beliefs of our particular culture. What is considered appropriate gender behavior in one culture may be looked down upon in another. In America, women often wear shorts and tank tops to keep cool in the summer. Think back to summer vacations to popular American tourist destinations where casual dress is the norm. If you were to travel to Rome, Italy to visit the Vatican, this style of dress is not allowed. There, women are expected to dress in more formal attire, to reveal less skin, and to cover their hair as a display of respect. Not only does culture influence how we communicate gender identities, it also influences the interpretation, understanding, or judgment of the gender displays of others (Kyratzis & Guo; Ramsey). Additionally, popular media, such as commercials and catalogs can dictate how culture communicates gender roles.

Feminism versus Feminisms

[edit | edit source]If you have a gender communication course on your campus you may have heard students refer to it as a “women’s class,” or even more misinformed, as a course in “male bashing.” When professors that teach this course hear such remarks, they are often saddened and frustrated: sad because those descriptors define the course as an unsafe place for male students, and frustrated because there is often a common misconception that only females are gendered. Courses in gender and communication serve as powerful places for both female and male students to learn about their own gender constructions and its influence on their communication with others.

Perhaps one of the reasons for the popular misconception that gender is exclusively female is that it has somehow been linked with the other f-word—-feminism. What sorts of images or thoughts come to mind when you hear or read the word feminism? Are they positive or negative? Where did you learn them? Is this a label you would use to define yourself? Why or why not?

Just as gender is not synonymous with biological sex, it is also not synonymous with feminism. As we stated earlier, gender refers to the socially constructed definitions of what it means to be female or male in a given culture. Feminism is a socio-political and philosophical position about the relationships between men, women and power. As a result, there is not one kind of feminism (Lotz; Bing; Marine & Lewis), thus this section is entitled feminisms. Just as members of republican, democratic, green, and independent political parties disagree and agree about values, causes of social conditions, and policy, so do feminists. Below we provide brief descriptions of thirteen types of feminism. These are not all the feminisms that exist but some of the most common in which you may have already come into contact.

- Liberal Feminism. Liberal Feminism is one of the most common types of feminism and is institutionalized in the organization, the National Organization of Women (NOW). Basic beliefs of this position are that women and men are alike in important ways and should receive equal treatment. Accordingly, supporters work for causes such as “equal pay for equal work,” gender equity in political representation, as well as equality in other social, professional, and civic causes. This movement is often referred to as second wave feminism. The first wave were the American and English suffragists of the early 1800-1900s. Some men were ahead of their time during first wave feminism. This image shows a pin from the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage.

- Radical Feminism. Growing out of a discontentment with their treatment in New Left political movements of the 1960’s, many women began addressing issues of oppression on a systemic level. They argued that oppression of women is a platform on which all other forms (race, class, sexual orientation) of oppression are based. Communication strategies such as “consciousness raising” and “rap groups,” and positions such as the “personal is political” grew out of this movement (Also second wave).

- Ecofeminism. Coming into consciousness in 1974, Ecofeminism unites feminist philosophy with environmental and ecological ideas and ethics. Ecofeminists see the oppression of women as one example of an overall oppressive ideology. Thus, supporters of this position are not just concerned with ending oppression of women but changing the value structure that supports oppression of the earth (i.e. deforestation), oppression of children (i.e. physical and sexual abuse), and oppression of animals (i.e. eating meat.).

- Marxist Feminism. Stemming from the work of Karl Marx, Marxist feminism focuses on the economic forces that work to oppress women. Specifically, Marxist feminists question how a capitalist system supports a division of labor that privileges men and devalues women. If you thought that women were catching up to men economically, think again. The U.S. census found that the salary gap between men and women is not improving. In 2014 women earned 78 cents for every dollar men made - the yearly wage difference could be about $39,157 for women and $50,033 for men. This is a classic example of economic oppression of women in our society.

- Socialist Feminism. Extending Marxist feminist thought, Socialist Feminists believe that women’s unpaid labor in the home is one of the fundamental causes of sexism and oppression of women. Moreover, patriarchy, the system of sex oppression is connected with other forms of oppression, such as race and class.

- Womanist. One criticism of liberal and radical feminism is that these two movements have been largely a movement for and about white women. These movements have often failed to address issues such as the interlocking nature of race, class, and sex oppression. Womanists, then, connect issues of race and sex when working against oppression.

- Lesbian Feminism. This type of feminism is connected with one’s sexual orientation. Important issues for this feminist perspective include fighting for marriage and adoption rights, fair and safe treatment in the workplace, and women’s health issues for gay and lesbian couples.

- Separatist Feminism. Instead of fighting against the patriarchal system, this position maintains that patriarchal systems of oppression cannot be changed. Thus, the best way to deal with patriarchy is to leave it. Separatists work toward the formation of women-centered communities that are largely removed from the larger society.

- Power Feminism. Power Feminism emerged in the 1990’s and urges women not to be victims. Power is derived not by changing a patriarchal structure but by gaining success and approval from traditionally male dominated activities. Although it labels itself feminist, this position is actually contradictory to some very basic feminist tenants. Instead of recognizing the interplay of cultural institutions and sexual oppression, Power Feminism takes a “blame the victim” position and asserts that if women are denied opportunity then it is their fault.

- Revalorist Feminism. Those who are Revalorist Feminists are dedicated to uncovering women’s history through writings, art, and traditional activities such as sewing. Once uncovered, they can be incorporated into educational curriculum, used as a basis for reevaluating existing theoretical and methodological perspectives, and receive a more positive or accepted place in society. Their approach is to move women’s positions, ideas, and contributions from the margin to the center.

- Structural Feminism. Unlike Liberal Feminists who contend that women and men are alike in important ways, Structural Feminism holds that men and women are not alike due to different cultural experiences and expectations. These different experiences produce dissimilar characteristics. Because women can bear children, for example, they are more nurturing and caring.

- First Wave Feminism. First Wave Feminism is generally referred to as the women’s suffrage movement that took place over a span of seven decades from the late 1800s to early 1900s. Its objectives were primarily political as it opposed officially mandated inequalities imposed on women by the government. It was considered to have been eventually successful when women gained the right to vote in 1920.

- Second Wave Feminism. Second Wave Feminism refers to efforts in the women's movement that took place in the 1960s and 1970s. Although second wave feminism still addressed legal discrimination against women, as did first wave, it also began movements in areas such as domestic violence, rape, sexual harassment, sexuality, reproductive rights, and issues in family and workplace settings. Second Wave Feminism is considered to have ended in the 1980s.

- Third Wave Feminism. Third Wave Feminism believes the best way to change patriarchy is to not replicate the strategies of second wave feminism, although it is vital to acknowledge their contributions. Instead, a feminist agenda should focus more on practice than theory, foster positive connections and relationships between women and men, and be inclusive of diversity issues and diverse people.

- Post Feminism. Post Feminism suggests that feminism has made sufficient progress at eliminating sexism in our society. There is a move away from sex (women and men) and a focus on the human experience. Though its members aren’t in 100% agreement of the meaning, they generally agree that feminism is over and we have reached equality. However, there is much disagreement about post feminism because many women and men experience inequality daily.

Just as there are many women’s movements, did you know that there are men’s movements too? Men’s movements also vary in their goals and philosophies. Some men’s movements are strong supporters of feminist positions while others resist feminist movements and seek to return to a time where sex roles were clearly defined and distinct. Just as women can consider themselves feminists, many men consider themselves as feminists too!

- Pro-Feminist Men. Pro-feminist men are the most closely aligned with the Liberal Feminist position. They share the belief that women and men are alike in important ways, thus, should have access to equal opportunities in work, politics, and the home. They do not stop at challenging the traditional roles for women. They also work for expanding the roles and opportunities of men. The ability to express emotions, to seek nurturing relationships, and to fight against cultural sexism are all concerns of Pro-Feminist Men. The organization NOMAS (National Organization for Men Against Sexism) represents this group of men. Quickly after the 2017 election that led to Donald Trump entering the White House, the March on Washington took place. Men and women marched together to show their resistance in the face of sexism. In order to communicate solidarity men, women and gender non-binary folks marched side by side.

- Free Men. Compared to Pro-Feminist men, Free Men – represented by organizations such as NOM (National Organization of Men), the National Coalition for Free Men, and MR, Inc. (Men’s Rights, Incorporated) – seek to restore the macho and independent image of men in culture. While they may acknowledge that women do suffer gender and sex oppression, the oppression leveled at men is far greater. Arguing that feminism has emasculated men, Free Men want women to return to roles of subordination and dependence.

- Mythopoetic. Founded by poet, Robert Bly, this group of men is a combination of the previous two perspectives. Although they believe that the man’s role is limiting and damaging to both men and women, they argue that there was a time when this was not the case. Masculinity, they claim, was originally tied to connection with the earth and it was the advent of technology, resulting in modernization and industrialization, and feminism that ripped men from their roots.

- Promise Keepers. Strongly aligned with a Christian belief system, Promise Keepers urge men to dedicate themselves to God and their families. They ask men to take a servant leadership role in their families, being involved in their homes as well as in work contexts.

- Million Man March. Like the Womanists who believe that a majority of feminisms do not adequately address issues of race and class oppression, many African-American males do not feel represented in the majority of men’s movements. Thus, on October 18, 1995, the leader of the nation of Islam, Minister Louis Farrakhan, organized the Million Man March to bring African American men together in Washington, D.C. Like, the Promise Keepers, this group asked men to dedicate themselves spiritually with the belief that this will help strengthen families. Since the march, two decades ago, people gather to observe the Holy Day of Atonement and reflect on the messages spoken that day and the ideas they wish to spread.

- Walk a Mile in Her Shoes. This annual event raises awareness of sexualized violence against women--by men. It was founded in 2001 by Frank Baird as a mile walk for men in women’s heels. The idea is to get men to walk the walk and then talk the talk to end sexualized violence. It is not only an event to raise awareness of violence against women but to offer resources to those needed and ultimately creating a united gender movement.

With the different groups or philosophical positions all communicating aspects of gender, the next section examines how gender is related to communication. Specifically we discuss what we study, gender development theories, prominent scholars in this specialization, and research methods used to study gender and communication.

Theories of Gender Development

[edit | edit source]We said earlier that gender is socially learned, but we did not say specifically just what that process looks like. Socialization occurs through our interactions, but that is not as simple as it may seem. Below we describe five different theories of gender development.

- Psychodynamic. Psychodynamic theory has its roots in the work of Viennese Psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud. This theory sees the role of the family, the mother in particular, as crucial in shaping one’s gender identity. Boys and girls shape their identity in relation to that of their mother. Because girls are like their mothers biologically they see themselves as connected to her. Because boys are biologically different or separate from their mother, they construct their gender identity in contrast to their mother. When asked about his gender identity development, one of our male students explained, “I remember learning that I was a boy while showering with my mom one day. I noticed that I had something that she didn’t.” This student’s experience exemplifies the use of psychodynamic theory in understanding gender development.

- Symbolic Interactionism. Symbolic Interactionism come from the work of George Herbert Mead and is based specifically on communication. Although not developed specifically for use in understanding gender development, the theory has particular applicability here. Because gender is learned through communication in cultural contexts, communication is vital for the transformation of such messages. When young girls are told to “sit up straight like a lady” or boys are told “gentlemen open doors for others,” girls and boys learn how to be gendered (as masculine and feminine) through the words (symbols) told to them by others (interaction).

- Social Learning. Social Learning theory is based on outward motivational factors. If children receive positive reinforcement they are motivated to continue a particular behavior and if they receive punishment, or other indicators of disapproval, they are more motivated to stop that behavior. In terms of gender development, children receive praise if they engage in culturally appropriate gender displays and punishment if they do not. When aggressiveness in boys is met with acceptance, or a “boys will be boys” attitude, but a girl’s aggressiveness earns them little attention, the two children learn different meanings for aggressiveness as it relates to their gender development. Thus, boys may continue being aggressive while girls may drop it out of their repertoire.

- Cognitive Learning. Unlike Social Learning theory that is based on external rewards and punishments, Cognitive Learning theory states that children develop gender at their own levels. The model, formulated by Lawrence Kohlberg, asserts that children recognize their gender identity around age three but do not see it as relatively fixed until the ages of five to seven. This identity marker provides children with a schema (a set of observed or spoken rules for how social or cultural interactions should happen) in which to organize much of their behavior and that of others. Thus, they look for role models to emulate maleness or femaleness as they grow older.

- Standpoint. Earlier we wrote about the important role of culture in understanding gender. Standpoint theory places culture at the nexus for understanding gender development. Theorists such as Patricia Collins and Sandra Harding recognize identity markers such as race and class as important to gender in the process of identity construction. Probably obvious to you is the fact that our culture, and many others, are organized hierarchically—some groups of people have more social capital or cultural privilege than others. In the dominant U.S. culture, a well-educated, upper-middle class Caucasian male has certain sociopolitical advantages that a working-class African American female may not. Because of the different opportunities available to people based on their identity markers (or standpoints), humans grow to see themselves in particular ways. An expectation common to upper middle-class families, for example, is that children will grow up and attend college. As a result of hearing, “Where are you going to college”? as opposed to “Are you going to college”? these children may grow up thinking that college attendance is the norm. From their class standing, or standpoint, going to college is presented as the norm. Contrast this to children of the economically elite who may frame their college attendance around the question of “Which Ivy League school should I attend?” Or, the first generation college student who may never have thought they would be in the privileged position of sitting in a university classroom. In all of these cases, the children begin to frame their identity and role in the society based on the values and opportunities offered by a particular standpoint.

What Do We Study When We Study Gender Communication?

[edit | edit source]Let’s take a moment to describe in more detail many of the specific areas of gender and communication study discussed in this chapter. You know by now that the field of Communication is divided up into specializations such as interpersonal, organizational, mass media. Within these particular contexts gender is an important variable, thus, much of the gender research can also be integrated into most of these specializations.

Gender and Interpersonal Communication

[edit | edit source]There are many kinds of personal relationships central to our lives wherein gender plays an important role. The most obvious one is romantic relationships. Whether it takes place in the context of gay, lesbian, bi-sexual, or heterosexual relationships, the gender of the couple will have an impact on communication in the relationship as well as relational expectations placed on them from the culture at large. After a man and woman marry, for example, a common question for family and friends to ask is, “So, when are you having a baby?” The assumption is when, not if. Since gay and lesbian couples must go outside their relationship for the biological maternal or paternal role, they may be less likely to be asked such a question.

Other interpersonal relationships occur in families and friendships where gender is a consistent component. You may have noticed growing up that the boys and girls in your household received different treatment around chores or curfews. You may also notice that the nature of your female and male friendships, while both valuable, manifest themselves differently. These are just a couple of examples that gender communication scholars study regarding how gender impacts interpersonal relationships.

Gender and Organizational Communication

[edit | edit source]While Liberal Feminist organizations such as NOW have made great strides for women in the workplace, gender continues to influence the organizational lives of both men and women. Issues such as equal pay for equal work, maternity and paternity leave, sexual harassment, and on-site family care facilities all have gender at their core. Those who study gender in these contexts are interested in the ways gender influences the policies and roles people play in organizational contexts. See the Case In Point for information on the current wage-gap in organizations.

Case In Point |

Gender and Mass Communication

[edit | edit source]A particular focal point of gender and communication focuses on ways in which males and females are represented in culture by mass media. The majority of this representation in the 21st century occurs through channels of mass media—-television, radio, films, magazines, music videos, video games, and the internet. From the verbal and nonverbal images sold to us as media consumers, we learn the “proper” roles and styles of being male and female in American culture. During World War II, for example, there was a shortage of workers in factories because many of the workers (men) were being sent overseas to fight. Needing to replace them to keep the factories in business, the media launched a campaign to convince women that the best way they could support the war effort was to go out and get a job. Thus, we saw a large influx of women in the workplace. All was fine until the war ended and the men returned home. When they wanted their jobs back they discovered that they were already filled—-by women! The media once again launched a campaign to convince women that their proper place was now back in the home raising children. Thus, many women left paid employment and returned to a more traditional role (This phenomenon is depicted in the film, Rosie the Riveter).

As media and technology increases in sophistication and presence, they become new sites of gender display and performance. More examples of this can be seen in the increase of women filling leadership roles and men portrayed in nurturing, home environments in television and advertising (Krolokke). The comedy series, “Up All Night,” that ran on NBC from September 2011 to December 2012 reflects this idea. The mom, Reagan, goes back to work as a talk show producer after having a baby while husband, Chris stays at home with their newborn. Yes, there is still a lack of strong female roles in the media. Fortunately for women, the Oscar winning actress, Reese Witherspoon has decided to do something about this. In 2012, Witherspoon “grew increasingly frustrated by the answers she got to her question, ‘What are you developing for women?’” (Riley). In her search for a production with a female lead she recalls discovering only “one studio that had a project for a female lead over 30,” and thought, “‘I’ve got to get busy.’ After getting busy, Witherspoon, along with female Australian producer Bruna Papandrea, started Pacific Standard Production Company that focuses on producing films with a strong female lead. Since the company’s start, Witherspoon and Papandrea have produced two films, “Gone Girl,” based on the novel by Gillian Flynn, and “Wild," the best-selling memoir by Cheryl Strayed; both released in December 2014. To read more about Witherspoon and her pursuit for women roles read the article by the Columbus Dispatch.

Are There Really Differences in Gender Communication Styles?

[edit | edit source]Many of us have had conversations with others about how different the “other” gender communicates. Countless books have been written claiming they have the answer for understanding the opposite gender. But what have we really learned about gendered ways of communicating? This section talks about language, the purpose of communication, patterns of talk, and nonverbal communication in relation to our gender.

Language

[edit | edit source]We have already discussed that one way language obscures women’s contributions to academic scholarship is by erasing the name from the ideas generated. Below we will discuss three other ways in which the English language demonstrates a positive bias toward the masculine and a negative bias toward the feminine.

- Generic “He”

The US Constitution states that “all men are created equal”. Through the history of this country, women have been told that this statement implies women are included. The fact is, this has not, and still is not, completely true. The two letters it would have taken to write “human” were deliberately left off because women were not seen as equal. Today this is still the case but steps are being made to work towards more inclusive terminology. Likely you have been told that when you write or speak to use what is referred to as gender-neutral language. This is an attempt to get away from the generic “he” and move toward inclusive pronouns. For example, using “he” when we mean “he or she.” Using gender-neutral language tells us to select the latter option. Another popular way this issue presents itself is with the use of titles that contain gender markers. Words such as “policeman,” “fireman,” “mailman,” and “chairman”; all suggest that the people who hold these positions are male. Over time, replacing the above titles with gender neutral ones such as “police officer,” “firefighter,” “mail carrier,” and “chairperson” have become the norm. This linguistic change has two main implications; 1) we don’t know the gender of the person being discussed, and 2) both males and females can perform these jobs. Since we have learned that language influences perception and constructs our reality, using language responsibly to reflect nonsexist attitudes is important (McConnell and Fazio; Mucchi-Faina; O Barr; Parks; Stringer & Hopper). In recent years, our language has been progressing even further. Instead of simply using she/he and men/women, we recognize that not every person will identify within those categories. Now we see it is more appropriate to use the term “people of all genders” to be more inclusive.

- Defining Men and Women

A second way in which language is biased against the feminine is the way it is used to define women versus men. One such way is to use descriptions based on accomplishments or actions to define males, while defining females in terms of physical features or their relationships to men. As First Lady, Michelle Obama received a lot of press coverage about her choice of clothing for public events, her professional career and accomplishments as a political figure were either downplayed, or used against her as evidence that she was not properly filling the role of First Lady. Another way language is used to define men and women is through the slang terms commonly used to refer to one sex or another. What are some common ones you hear on your campus and within your circle of friends? Are women “chicks?” Are men “dudes?” What about explicit sexual references to women as a “piece of ass” or men as “dicks?” These are just some ways in which sexual terms are used to define us. Numerous studies have shown that there are many more sexual terms used for women than men.

Case In Point |

- Naming Reality

The final way language influences the ways we understand gender is in the reality it creates for us. In the same way that the term “fireman” suggests that only males can do this job, creating terms to name experiences (or not having such terms) defines what we can or cannot experience. Undoubtedly, you are familiar with the term “sexual harassment” and may be familiar with your campus policy for reducing its occurrence. Did you know that this term did not come into existence until 40 years ago? Did sexual harassment occur prior to 40 years ago? Of course it did! The point is that until there was a term for such behavior (emerging in 1974) there was no way for women (as they are the most common victims/survivors of this behavior) to either talk about what was happening to them or to fight against the behavior. Imagine the difficulty inherent in trying to create a policy or law to prohibit behavior when there is no term for such behavior! With the advent of the term and the publicity about this issue generated by the bravery of Anita Hill when she testified against current Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, most organizations have policies to protect employees from sexual harassment. Without the language, this would have been impossible to accomplish: “the development of a vocabulary with which to accurately describe one’s experiences is an important process during which one needs to reflect on the political implications of that experience” (DeFrancisco & Palczewski 119).

The use of a generic or universal he, the use of nonparallel descriptors for different genders, and vocabulary are just some of the ways language influences our experiences as one gender or another. See if you can think of other examples.

Purpose of Communication

[edit | edit source]Starting in childhood, girls and boys are generally socialized to belong to distinct cultures and thus, speak in ways particular to their own gender’s rules and norms (Fivush; Johnson; Tannen). This pattern of gendered socialization continues throughout our lives. As a result, men and women often interpret the same conversation differently. Culturally diverse ways of speaking can cause miscommunication between members of each culture or speech community. These cultural differences are seen in the simple purpose of communication.

For those socialized in a feminine community, the purpose of communication is to create and foster relational connections with other people (Johnson; Stamou). On the other hand, the goal for men’s communication is to establish individuality. This is done in a number of ways such as indicating independence, showing control, and entertaining or performing for others.

Although our previous discussion of feminist movements for women and men indicates that gender roles are changing, traditional roles still influence our communication behaviors. Because men have traditionally been expected to work outside the home to provide financial support for the family, they need to demonstrate their individual competence as this is often the criterion for raises and promotions. Conversely, because women have been expected to work inside the home to provide childcare, household duties, and other social functions the need to create interpersonal bonds is crucial. Thus, it is important to understand the cultural reasons and pressures for the differences in communication, rather than judge one against the other devoid of context.

Patterns of Talk

[edit | edit source]One way to think of gender communication is in terms of co-cultures or speech communities. A speech community is a “community sharing rules for the conduct and interpretation of speech” (Hymes 54). Muted group theory (Kramerae) explains the societal differentiation of gender and its corresponding language development. This develops on two levels:

- Women (and members of other subordinate groups) are not as free or as able as men are to say what they wish, when and where they wish, because the words and the norms for their use have been formulated by the dominant group, men.

- Women’s perceptions differ from those of men because women’s subordination means they experience life differently. However, the words and norms for speaking are not generated from or fitted to women’s experiences (1).

Thus, when discussing patterns of talk we conceptualize them as occurring in different speech communities or co-cultures based on historical, cultural and economic expectations of a given co-culture. For the different genders, we develop different patterns of talk based on expectations placed on us.

- Feminine Speech Community

When cultures have different goals for their communication, this results in unique communication strategies and behaviors. When the goal is connection, members of a feminine speech community are likely to engage in the following six strategies—equity, support, conversational “maintenance work,” responsiveness, a personal style, and tentativeness. The image here shows two women having lunch in-between classes. What sort of communication might be taking place? The use of cell phones might appear disruptive but to these women it could be a form of equity, they are both comfortable and relaxed in each other’s company.

Showing equity in conversation means showing that you are similar to others. To do this one might say, “That happened to me too,” or “I was in a similar situation.” Showing support conversationally involves the expression of sympathy, understanding, and emotions when listening or responding to others. Sotirin suggests “women use bitching to cope with troubles by reaffirming rapport; men address troubles as problems of status asymmetry and respond with solutions. The characterization minimizes the political import of women’s bitching; it’s not political but interpersonal; not transformative but cathartic” (20). Have you ever felt as if you were the one in the conversation who had to keep the conversation moving? This is conversational maintenance at work. This work is performed by asking questions and trying to elicit responses from others. A typical family dinner conversation might begin with one of the parents asking their children, “What happened in school today?” The purpose is to initiate dialogue and learn about others to fulfill the purpose of communication—to maintain connection with others.

When listening to others we often respond in various ways to show that we are attentive and that we care about what the other person is saying. Responsiveness includes asking probing questions such as, “How did you feel when that happened?” or, “Wow, that’s interesting, I’ve never thought of that before.” Displaying a personal style refers to all the small details, personal references, or narratives that a person uses to explain her/his ideas. A professor explaining the stages of friendship development might supplement the model with how a particular friendship developed in their life.

The final quality, tentativeness, involves a number of strategies and has invoked a multiplicity of interpretations. A student might say, “This is probably a stupid question, but…” as a way of qualifying her/his question. Turning statements into questions is another way of showing tentativeness. This is done with tag questions or intonation. Tag questions are phrases tacked onto the end of a sentence. In the statement, “I liked the film, didn’t you?” the “didn’t you?” is the tag. If you have studied French, this is similar to the use of “n’est pas.” When we use our voice to make a statement into a question (intonation) we make the last syllable raise. For example, if your roommate asks you, “what do you want for dinner?” you could say “pizza” to make it a question (“pizza?”) or a statement (“pizza.”) Another way to show tentativeness is through verbal hedges such as, “I sort of think I was too sensitive.”

As you read the types of tentativeness, what were your reactions? How do you feel when someone communicates this way? Generally, scholars have offered four explanations for tentativeness. First, is that this style represents a lack of power, self-confidence, or assuredness on the part of the speaker. Lakoff theorized that the powerlessness in speech mirrored women’s powerlessness in the culture. Another interpretation is that to understand tentativeness we must examine the context in which such speech occurs. The relative power between two speakers may cause the one with less power to communicate tentatively to the other. Do you use markers of tentativeness when speaking with those in power such as your boss, teachers, or parents?

- Masculine Speech Community

When the goal is independence, members of this speech community are likely to communicate in ways that exhibit knowledge, refrain from personal disclosure, are abstract, are focused on instrumentality, demonstrate conversational command, are direct and assertive, and are less responsive. Showing knowledge in conversation gives speakers the opportunity to present themselves as competent and capable. If someone has a problem at work one might respond, “You should do this …” or “The best way to deal with that is …” This strategy is sometimes referred to as a “communication tool box.” While some may interpret this as bossy, responding in a manner that tries to fix a problem for someone you care about makes a lot of sense.

The next two features—minimal personal disclosure and abstractness—are related. When we refrain from personal disclosure we reveal minimal or no personal information. While giving a lecture on communication anxiety in a public speaking class, a professor may use examples from famous people rather than revealing their own experiences. Likewise, when we speak in less personal terms our conversation tends to become more abstract. Think back to the traditional roles for men and women for a moment. Since men typically have been more involved in the public rather than the private sphere, it makes sense that their communication would be more abstract and less personal.

A masculine communication style tends to be focused on instrumental tasks. This is particularly true in the case of same sex friendships. Like the “tool box” or a problem solving approach to communication, when talk is instrumental it has a specific goal or task. It is used to accomplish something. Take baseball or football, for example. The talk that is used in these activities is strategic. In the case of male friendships it is more likely that males will get together to do something. Whether the activity is rock climbing, going to lunch, or helping someone move, the conversation is instigated by a particular activity. While female friends also like to engage in activities together, they are much more likely to get together “just to talk.”

Conversational command refers to the ability to control or manage conversation. This can be done by controlling which topics are discussed, interrupting, or being the one to control the turn taking in conversation. A popular stereotype is that females talk a lot, but most research shows that males talk more than females. More talk time is another way to demonstrate conversational command.

Directness is another feature of masculine communication. This refers to the use of more authoritative language and minimal use of tentativeness. Finally, males generally perform “minimal response cues” (Parlee). Response cues include saying, “mmm” or “go on” while nodding when listening to others. Fewer verbal indicators of sympathy, empathy, or understanding are likely to characterize this style of talk. While members of this speech community may be less likely to verbally express sympathy or other similar emotions, this is not the same as saying the members of the community do not feel such emotions. People of different genders feel and care for others in a variety of ways. The difference is how they are communicated, not if they are communicated.

The identification of “Toxic Masculinity” is leading to a transformation in the way that males are portrayed in the media. “We think of manhood as eternal, a timeless essence that resides deep in the heart of every man” but it is not as easy as that (Kimmel). Some companies such as Axe body spray and Gillette have recognized this change and have taken advantage of the need for positive representation. For more information of this movement view their “Find Your Magic” commercial. Stepping away from the stereotypical male communication patterns is beneficial for men and women.

Hyper Masculinity is also portrayed in commercials and print media. Axe Body Spray’s use of angels falling for the scent of a man is one example of the ways in which the media try to communicate the ideal male. In a 2006 article for The University of Northern Iowa Journal of Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity, Professor Thomas J. Scheff spells out the complications that lead to Hyper Masculinity by saying, “Since it appears that most men in our society are more alienated/repressed than most women, the idea of hypermasculinity is used to develop a theory of conflict. The combination of alienation with the repression of vulnerable emotions suggests a biosocial doomsday machine that leads to cascading violence and destructiveness."

As you were reading about the feminine and masculine speech communities you were probably thinking to yourself, “Hey, I am a woman but I have a lot of masculine communication traits,” or “I know some men who speak in a more feminine style.” As you think and reflect more on these ideas you will realize that all of us are capable of speaking, and do speak, the language of multiple gender cultures. Again, this is one of the reasons it is important to make a distinction between gender and sex. Our gender construction and the contexts in which we speak play a large role in the ways we communicate and express our gender identity. Both men and women may make conscious choices to speak more directly and abstractly at work, but more personal at home. Such strategic choices indicate that we can use our knowledge about various communication styles or options to make us successful in many different contexts.

Nonverbal Communication

[edit | edit source]Because you know how important nonverbal communication is to the production of meaning you may have wondered about the gendered nature of nonverbal communication. Below we discuss seven areas of nonverbal communication and the role of gender in each. We examine: Artifacts, Personal Space and Proxemics, Haptics, Kinesics, Paralanguage, Physical Attributes, and Silence

- Artifacts

Earlier in the chapter we mentioned the pink and blue blankets used to wrap girl and boy babies after birth. These are examples of artifacts that communicate gender. Simply speaking, personal artifacts are objects that humans use to communicate self-identity. The jewelry we choose to wear (or not wear) communicates something about our personal tastes and social roles. Our clothes indicate a preference for certain designers or fashions, or may be used to subvert dominant fashion trends and expectations. An American male who wears a skirt or sarong may be trying to challenge the cultural norm that says pants and shorts are the only appropriate clothes for men.

Artifacts that are an early influence on gender construction are the toys we are given as children. What are typical girl and boy toys and what kind of play do they inspire? You are probably thinking of dolls for girls and cars and trucks for boys. Just walk through the aisles of your local toy store and you will have no difficulty discovering the “girl” aisle (it’s pink) and the boy aisle (it’s darker colors). Typically toys for boys are more action-oriented and encourage competition. Girls’ toys, on the other hand, encourage talk (Barbies talk to each other and role play) and preparation for traditional female roles (playing house). If you think products (toys) are only gendered at a young age, pay close attention when you watch television commercials and look through magazines. What kinds of products do women typically sell? What do men sell? How are gender-neutral products (cigarettes for example) sold to both women and men?

- Personal Space and Proxemics

As you recall, the study of space and our use of it (proxemics) has two important dimensions. First, we understand space as our personal space, or the bubble in which we feel comfortable. When someone stands or sits too close to you, you may react by pulling away and describe the interaction as “they invaded my space.” Second, space can be thought of in terms of the kinds of physical spaces we have access to. Were some rooms in the family home off limits to you as a child? Relative to both kinds of space is power. People with more power in society are able to invade the space of those with less power with few repercussions. Those with more power also have access to more and better spaces. For example, the upper-class often own multiple homes in desirable locations such as the beach or high-priced urban areas.

What does all of this have to do with gender? Go back to the creation of power and ask yourself, “Which gender in American society holds the most power?” While there are exceptions, most of the time the masculine gender holds the most powerful positions in our culture. Thus, males typically have access to greater space. In the homes of many heterosexual couples, the father has a den and a garage that was for his use only. Mothers are often limited to shared space such as the kitchen and living areas. Not only is there a lack of private space, but also the tasks associated with each (cooking in the kitchen) are work as opposed to the hobbies that take place in the garage (rebuilding cars). What are some ways that space was gendered in your family? For more information, watch this video, which discusses space as nonverbal communication.

- Haptics

People of all genders in our culture use touch to communicate with others. However, there are differences in both the types of touch used and in the messages conveyed (Lee & Guerrero; Guerrero & Smith). Women are more likely to use touch to express support or caring, such as touching someone on the shoulder or giving them a hug. Men are more likely to use touch to direct actions of another. The relative power of men to women, coupled with a greater level of social power that can manifest itself in unwanted closeness or touching, have been linked with the problems of sexual harassment and domestic violence (May; McLaughlin). However, men do not use touch only to show control. Men use touch to display affection and desire to romantic partners, to communicate caring and closeness to children, and to show support to friends. Since men are culturally sanctioned for showing caring through touch, especially to other men, a choice to do so is a conscious choice to challenge gender stereotypes for men. Another strategy for touch between men is to create contexts in which it is acceptable such as wrestling, play punching or fighting, or football.

- Kinesics

Like haptics, men and women use body language differently and to convey different meanings. Coinciding with cultural messages, men use their bodies to signal strength and control while women use theirs to communicate approachability and friendliness. Women, for example, smile more often than men and Caucasian women do this more than African-American women (Halberstadt & Saitta). Whether the cause is social or biological, men tend to take up more space and encroach on others’ space more often than females.

- Paralanguage

Consistent with a communication goal of maintaining and fostering relationships with others, women tend to use more listening noises or back-channeling. Such noises are “mmm,” “ah,” and “oh” and are often accompanied by nodding the head. Often they mean, “I am listening and following what you are saying. Keep going.” While men also make listening noises, they do so less frequently and often the meaning is “I agree.” Hopefully, you can see how this could cause some miscommunication between the sexes. Likewise, being aware of this difference can reduce miscommunication. For example, when two people (Courtney and Juan) talk, Juan will often ask Courtney, “are you saying ‘mm hmm” because you agree, or are you just listening?” In doing so, he is trying to determine which gendered approach to listening paralanguage Courtney is employing.

- Physical Attributes

Another area of nonverbal communication that has gendered implications is physical attributes—the most common one for gender being body size and shape. If you were socialized in America you probably know how men and women are “supposed” to look. Men should be larger and physically strong while women should be smaller—very thin. These cultural pressures cause both men and women to engage in dangerous behaviors in an attempt to achieve an ideal physical body. Women are more likely to engage in dieting to become thin and men are more likely to weight-lift to excess, or take steroids, to increase muscle mass. The cultural messages for both sexes are physically and emotionally dangerous. Too severe dieting or steroid use can permanently damage the physical body and too much attention to appearance can harm one’s self esteem and take time away from pursuing other activities such as school, career, hobbies, and personal relationships.

- Silence

A final area of nonverbal communication that has had large implications on gender is silence. Throughout history women have been silenced in all cultures across the world. In chapter 4, we were introduced to one of the early Greek female rhetoricians, Aspasia. We don’t know much about her and her work because women have been systemically left out of our traditional history lessons. Women’s work has often been discredited, published under a male pseudo name, or males have passed it off as their own work. More recently, there’s a great episode of Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey entitled, “Sisters of the Sun,” that demonstrates women making large strides in the study of stars in our galaxy, yet they are rarely mentioned in our history books. Historically, achievements of females have been silenced.

This systematic silencing of women has led many women to hesitate against speaking out against sexual assault, harassment, violence, or rape that they have experienced. They are often silenced due to uneven power dynamics, the fear of victim blaming, threats, and a countless number of forces. Fortunately, technological and social media efforts of today are working to break this silence. In October 2014, a new hash tag on Twitter was trending in the US and Canada that reads #BeenRapedNeverReported. Rape victims tweet about past experiences they felt they could not talk about and include the hashtag. One tweet reads, “Ive #beenrapedneverreported because he was military, and I am a vocal feminist slut. Who would the media believe? Not me. #DoubleStandards.” You can access the full article here.

In another example, Jatindra Dash reports, women in India who suffer from domestic violence tend to keep quiet because they are “scared of … [their] husband, mistrustful of the police and worried what ... family and neighbors would think.” India is trying to combat this silence with an ATM-like machine that allows people to report their testimony into a microphone that the police station receives, contacts the person who reports it, and may make an arrest. You can read about this new kiosk here. Today’s technology and media may just help disrupt the long history of silence faced by women either placed on them by others or by themselves.

Finally, in celebration of this time in history “The Silence Breakers” were named as a group, Time Magazine’s Person of The Year. This list was created after multiple people, including many celebrities, broke their silence about experiencing sexual assault. Actors like Ashley Judd, Terry Crews, Rose Mcgowan and others all came forward about facing sexual harassment and assault head-on. The Silence Breakers were up against many other fine people like, Colin Kaepernick, The “Dreamers” and Patty Jenkins, the director of Wonder Woman.

Summary

[edit | edit source]In this chapter you have been exposed to the specialization of gender and communication. You learned that gender communication is “the social construction of masculinity or femininity as it aligns with designated sex at birth in a specific culture and time period. Gender identity claims individuality that may or may not be expressed outwardly, and may or may not correspond to one’s sexual anatomy” (Pettitt). It is important to remember as we discuss gender and communication that there is a difference between sex and gender. Sex refers to the biological distinctions that make us male or female. Gender is the socially constructed enactment of what it means to be a man or a woman. We are generally born as either male or female, but taught how to be men and women.

People of all identities are gendered and experience their genders in a variety of ways. As a result of how gender is manifested, many feminist, men, and other activist groups have formed for the purpose of banding together with others who understand gender in similar ways. We discussed 12 types of feminisms and five different men’s groups that focus on various approaches for understanding and enacting gender.

There are a variety of theories that seeks to explain how we form gender. Remember that theories are simply our best representations of something. Thus, theories of gender development such as Psychodynamic theory, Social Interactionism, Social Learning theory, Cognitive Learning theory, and Standpoint theory are all attempts to explain the various ways we come to understand and enact our genders.

Like with many other specializations in the field of Communication, gender communication applies to a variety of other specializations. Interpersonal communication, organizational communication, and mass communication are specializations that are particularly ripe for exploring the impact of gender and communication. Gender communication research continues to explore gender in these contexts, thus helping redefine how gender is understood and behaved.

We explored differences in gender communication styles by looking at language, the purpose of communication, patterns of talk, and nonverbal communication. While impossible to come to a definitive conclusion, gender and communication studies generally promotes the idea that the differences in gender communication are socially learned and are thus fluid and dynamic. Males and females learn to communicate in both masculine and feminine styles and make strategic choices about which style is more effective for a given context.

Discussion Questions

[edit | edit source]- Even though sex and gender are not correlated, why do so many people struggle to differentiate these very different aspects of identity?

- What are some ways that your gender was communicated or taught to you by your parents? Other family members? Your school? Friends? Church?

- Many people claim to be in favor of equality but do not consider themselves a feminist. Why do you think that is?

- Did you know there were so many/if any Men’s movements, all with different goals, before reading this chapter? What does our limited knowledge of men’s movements imply?

- What ways do you break traditional gender roles?

- Do you feel drawn to any of the types of feminisms listed in the chapter? Why or why not?

Key Terms

[edit | edit source]- androgyny

- cognitive learning

- culture

- ecofeminism

- feminine speech community

- feminism

- free men

- gender

- gender communicated

- gendered

- lesbian feminism

- liberal feminism

- marxist feminism

- masculine speech community

- million man march

- muted group theory

- mythopoetic

- power feminism

- pro-feminist men

- promise keepers

- psychodynamic

- psychological theories

- radical feminism

- revalorist feminism

- separatist feminism

- sex

- socialist feminism

- social learning

- speech community

- standpoint theory

- structural feminism

- symbolic interactionism

- third-wave feminism

- womanist

References

[edit | edit source]"About The Million Man March | NOI.org – The Nation of Islam Official Website |." NOIorg The Nation of Islam Official Website. Nation of Islam, n.d. Web. 10 Dec. 2014.

"Agender." Nonbinary Gender Visibility, Education and Advocacy Network. N.p., 2 Aug. 2014.

Astrophy. "I Am Genderfluid." Groupthink. N.p., 4 Apr. 2014. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Beal, Carole R. Boys and girls: The development of gender roles. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

Bell, Elizabeth. "Operationalizing Feminism: Two Challenges For Feminist Research." Women & Language 33.1 (2010): 97-102. Communication & Mass Media Complete.

Bing, Janet. "Is Feminist Humor An Oxymoron?." Women & Language 27.1 (2004): 22-33. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web.

Collins, Patricia Hill. "Learning from the outsider within: The sociological significance of Black feminist thought." Social problems (1986): S14-S32.

Dash, Jatindra. "India's Abused Women Break Their Silence Using ATM-type Kiosk." India's Abused Women Break Their Silence Using ATM-type Kiosk. N.p., 3 Nov. 2014.

DeFrancisco, Victoria Pruin, and Catherine H. Palczewski. Communicating gender diversity: A critical approach. Sage Publications, 2007.

Fivush, Robyn, et al. "Gender Differences in Parent–Child Emotion Narratives." Sex roles 42.3-4 (2000): 233-253.

"Genderqueer." Gender Wiki. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2014.

Gilbert, Lucia A. Two Careers, One Family: The Promise of Gender Equality. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications, 1993. Print.

Guerrero, Laura, and Adam Smith. "Touch In Cross-Sex Relationships Between Superiors And Subordinates: Perceptions Of Expectedness, Inappropriateness, And Sexual Harassment." Conference Papers -- National Communication Association: 2009.

Halberstadt, Amy G., and Martha B. Saitta. "Gender, nonverbal behavior, and perceived dominance: A test of the theory." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53.2 (1987): 257.

Harding, Sandra G. Whose science? Whose knowledge?: Thinking from women's lives. Cornell University Press, 1991.

Howard, Judith A., and Jocelyn A. Hollander. Gendered situations, gendered selves: A gender lens on social psychology. Vol. 2. Rowman & Littlefield, 1997.

Hymes, Dell. "Models of the interaction of language and social setting." Journal of Social Issues. 23.2 (1967): 8-28.

Johnson, Fern L. Speaking culturally: Language diversity in the United States. Sage, 1999.

Kohlberg, Lawrence. A Cognitive-Developmental Analysis of Children's Sex-role Concepts and Attitudes. 1966.

Kramarae, Cheris. Women and Men Speaking: Frameworks for Analysis. (1981).

Kroløkke, Charlotte. "Impossible Speech”? Playful Chat and Feminist Linguistic Theory." Women and Language (2003): 15-21. Print.

Kyratzis, Amy, and Jiansheng Guo. "Preschool girls' and boys' verbal conflict strategies in the United States and China." Research on Language and Social Interaction 34.1 (2001): 45-74.

Lakoff, Robin Tolmach. Language and woman's place: text and commentaries. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Lee, Josephine W., and Laura K. Guerrero. "Types of touch in cross-sex relationships between coworkers: Perceptions of relational and emotional messages, inappropriateness, and sexual harassment." Journal of Applied Communication Research 29.3 (2001): 197-220.

Lorber, Judith. Paradoxes of gender. Yale University Press, 1994.

Lotz, Amanda D. "Communicating third-wave feminism and new social movements: Challenges for the next century of feminist endeavor." Women and Language 26.1 (2003): 2-9.

Marine, Susan B, and Ruth Lewis. "“I'm in This for Real”: Revisiting Young Women's Feminist Becoming." Women's Studies International Forum, 47 (2014): 11-22.

May, Larry. "Many Men Still Find Strength in Violence." The Chronicle of Higher Education [H.W. Wilson - EDUC], 45.6 (1998): B7.

Mcconnell, Allen R., and Russ H. Fazio. "Women as Men and People: Effects of Gender-Marked Language." Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22.10 (1996): 1004-013.

McLaughlin, Heather, Christopher Uggen, and Amy Blackstone. "Sexual harassment, workplace authority, and the paradox of power." American sociological review 77.4 (2012): 625-647.

Mead, George Herbert, and Charles Morris. Mind, Self & Society from the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. Chicago: The University of Chicago press, 1934.

Mucchi-Faina, Angelica. "Visible or Influential? Language Reforms and Gender (In)equality." Social Science Information, 44.1 (2005): 189-215.

O'Barr, William M. Language and Patriarchy, in Gender Mosaics: Social Perspectives. Edited by Dana Vannoy, Roxbury, Mass.: Roxbury Press. 2001.

Parks, Janet, and Mary Roberton. "Explaining Age and Gender Effects on Attitudes Toward Sexist Language." Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 24.4 (2005): 401-411.

Parlee, Mary B. "Conversational politics." Psychology Today. (1979): 48-56.

Pettitt, Jessica. The Trans Umbrella. Tucson, AZ: Jessica Pettitt, I Am... Social Justice and Diversity Facilitator and Trainer, 2009. 1-3. Print.

Ramsey, E Michele. "Addressing Issues of Context in Historical Women's Public Address." Women's Studies in Communication, 27.3 (2004): 352-376.

Riley, Jenelle. "Reese Witherspoon Leads Push on Roles for Women." The Columbus Dispatch. N.p., 10 Oct. 2014.

Sotirin, Patty. "'All They Do is Bitch Bitch Bitch': Political and Interactional Features of Women's Officetalk." Women and Language, 23.2 (2000): 19-25.

Stamou, Anastasia G, Katerina S Maroniti, and Konstantinos D Dinas. "Representing “traditional” and “progressive” Women in Greek Television: The Role of “feminine”/“masculine” Speech Styles in the Mediation of Gender Identity Construction." Women's Studies International Forum, 35.1 (2012): 38-52.

Stanley, Julia P. “Paradigmatic woman: The prostitute." I, D.L. Shores (Ed.), Papers in language variation. Birmingham: University of Alabama Press, 1977. Print.

Stephen, T. "Concept Analysis of Gender, Feminist, and Women's Studies Research in the Communication Literature." Communication Monographs, 67.2 (2000): 193-214.

Stringer, Jeffrey L, and Robert Hopper. "Generic 'He' in Conversation?." Quarterly Journal of Speech, 84.2 (1998): 209.

Tannen, Deborah. You Just Don't Understand: Women and Men in Conversation. New York, NY: Morrow, 1990. Print.

Tannen, Deborah. Talking from 9 to 5: How Women's and Men's Conversational Styles Affect Who Gets Heard, Who Gets Credit, and What Gets Done at Work. New York: W. Morrow, 1994.

Vannoy, Dana. Gender Mosaics: Social Perspectives: Original Readings. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury Pub., 2001. Print.

Wallace, Kelly. "Baseball Sensation Mo'ne Davis' Impact on Girls and Boys." CNN 20 Aug. 2014. Web. <Baseball sensation Mo'ne Davis' impact on girls and boys (CNN) By: Wallace, Kelly. http://www.cnn.com/2014/08/20/living/mone-davis-baseball-sensation-impact-girls-parents>.

"Welcome | Walk a Mile in Her Shoes." Welcome | Walk a Mile in Her Shoes. Venture Humanity, Inc., n.d.