Saylor.org's Comparative Politics/Case Study: The Arab Spring

FORWARD

[edit | edit source]In December 2011, the last U.S. combat troops were withdrawn from Iraq after an almost 9-year presence in that country. This day was welcomed by the U.S. public after years of sacrifice and struggle to build a new Iraq. Yet, the Iraq that U.S. troops have left at the insistence of its government remains a deeply troubled nation. Often Iraqi leaders view political issues in sharply sectarian terms, and national unity is elusive. The Iraqi political system was organized by both the United States and Iraq, although over time, U.S. influence diminished and Iraqi influence increased. In this monograph, Dr. W. Andrew Terrill examines the policies of de-Ba’athification as initiated by the U.S.-led Coalition Provision Authority (CPA) under Ambassador L. Paul Bremer and as practiced by various Iraqi political commissions and entities created under the CPA order. He also considers the ways in which the Iraqi de-Ba’athification program has evolved and remained an important but divisive institution over time. Dr. Terrill suggests that many U.S. officials in Iraq saw problems with de-Ba’athification, but they had difficulties softening or correcting the process once it had become firmly established in Iraqi hands. Other U.S. policymakers were slower in recognizing the politicized nature of de-Ba’athification and its devolution into a process in which both its Iraqi supporters and opponents viewed it as an instrument of Shi’ite revenge and political domination of Sunni Arabs.

Dr. Terrill’s monograph considers both the future of Iraq and the differences and similarities between events in Iraq and the Arab Spring states. He has examined both Ba’athism as a concept and the ways in which it was practiced in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. He notes that the initial principles of Ba’athism were sufficiently broad as to allow their acquisition by a tyrant seeking ideological justification for a merciless regime. His comprehensive analysis of Iraqi Ba’athism ensures that he does not overgeneralize when drawing potential parallels to events in the Arab Spring countries. Dr. Terrill considers the nature of Iraqi de-Ba’athification in considerable depth and carefully evaluates the rationales and results of actions taken by both Americans and Iraqis involved in the process.

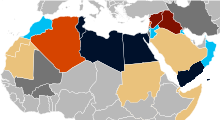

While there are many differences between the formation of Iraq’s post-Saddam Hussein government and the current efforts of some Arab Spring governing bodies to restructure their political institutions, it is possible to identify parallels between Iraq and Arab Spring countries. Some insights for emerging governments may, correspondingly, be guided by a comprehensive understanding of these parallels. The Arab Spring revolutions that have overthrown the governments of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen at the time of this writing are a regional process of stunning importance. While these revolutions began with a tremendous degree of hope, great difficulties loom in the future. New governments will have to apportion power, build or reform key institutions, establish political legitimacy for those institutions, and accommodate the enhanced expectations of their publics in a post-revolutionary environment. A great deal can go wrong in these circumstances, and it is important to consider ways in which these new governing structures can be supported, so long as they remain inclusive and democratic. Any lessons that can be gleaned from earlier conflicts will be of considerable value to the nations facing these problems as well as to their regional and extra-regional allies seeking to help them.

The Strategic Studies Institute is pleased to offer this monograph as a contribution to the national security debate on this important subject as our nation continues to grapple with a variety of problems associated with the future of the Middle East and the ongoing challenge of advancing U.S. interests in a time of Middle East turbulence. This analysis should be especially useful to U.S. strategic leaders and intelligence professionals as they seek to address the complicated interplay of factors related to regional security issues, the future of Iraq, and the support of local allies and emerging governments. This work may also benefit those seeking a greater understanding of long- range issues of Middle Eastern and global security. It is hoped that this work will be of benefit to officers of all services as well as other U.S. government officials involved in military and security assistance planning.

DOUGLAS C. LOVELACE, JR.

Director

Strategic Studies Institute

SUMMARY

[edit | edit source]The presence of U.S. combat troops in Iraq has now come to an end, and the lessons of that conflict for the United States and other nations will be debated for some time to come. It is now widely understood that the post-invasion policy of de-Ba’athification, as practiced, had numerous unintended consequences that made building Iraqi civil society especially difficult following the U.S.-led invasion. The U.S. approach to this policy is often assessed as having underestimated both the dangers of increased sectarianism in Iraq and the need for strong efforts to manage ethnic-sectarian divisions. The Iraqi government’s approach to de-Ba’athification was, nevertheless, much more problematic due to its openly biased and sectarian nature. However well-intentioned, de-Ba’athification originally was as a concept, in practice it had a number of serious problems. These problems intensified and became more alarming as the de-Ba’athification process became increasingly dominated by the Iraqis and American oversight over that program gradually evaporated. At that time, it came to be viewed as an instrument of revenge and collective punishment by both the Iraqis that administered de-Ba’athification and those that were targeted by these policies.

A comprehensive review of Iraqi de-Ba’athification is necessary before making any assertions about the lessons of these policies for either Iraq or the larger Arab World. Understanding de-Ba’athification begins with a consideration of U.S. policies and goals for Iraq. After the removal of the Saddam Hussein regime, the U.S. leadership had a choice of implementing limited de-Ba’athification or seeking a much more sweeping program. They initially chose the latter course because it was deemed especially important to eliminate the last vestiges of Saddam Hussein’s regime to prevent a similar type of government from reestablishing itself. In making this choice, advocates of deep de-Ba’athification pointed to the history of Ba’athist conspirators rising to power through infiltrating government institutions and seizing power in undemocratic ways. This comprehensive approach nevertheless made it extremely difficult for Iraq’s Sunni Arab leaders to accept the post-war political system. Many U.S. leaders became concerned about this problem over time, but they had increasing difficulties moderating Iraqi administration of de-Ba’athification efforts.

Despite the time that has elapsed since the initial decisions on de-Ba’athification, these issues remain vital for the future of Iraq. The Sunni Arab insurgency that developed after the U.S.-led invasion reinforced the popularity of de-Ba’athification among many of Iraq’s Shi’ite Arabs, thereby keeping the policy alive. Many Shi’ites also agreed with U.S. concerns about the potential emergence of a new Sunni-dominated regime that would once again seize and retain power. A quasi-legal de-Ba’athification Commission (now known as the Justice and Accountability Commission) continues to exist in Iraq and recently played a dramatic role in disqualifying some leading Sunni candidates in the 2010 parliamentary elections. This commission could not have remained relevant without the support of a variety of important Iraqi politicians, including the current prime minister. Likewise, Iraqi Prime Minister Maliki arrested large numbers of so-called “Ba’athists” in 2011, shortly before the final withdrawal of U.S. troops. Under these circumstances, the legacy of de-Ba’athification and the future of this concept within the Iraqi political system may yet have serious consequences for Iraq’s ability to build a unified and successful state.

Many Americans and Iraqis of diverse political orientations have argued that de-Ba’athification and the nature of sectarianism in Iraq involved a large number of lessons that other countries may wish to consider in the context of future political transitions. This argument has found considerable resonance among some citizens in the “Arab Spring” states where popular uprisings have ousted some long-serving dictators. Many of the new revolutionaries consider Iraq’s problems as a cautionary tale that must be understood as they move forward in establishing new political systems. In particular, it is now understood that loyalty commissions led by politicians and set up to identify internal enemies can take on a life of their own and become part of a nation’s power structure. Once this occurs, such organizations are exceedingly difficult to disestablish. Likewise, the basic unfairness of collective punishment has again been underscored as an engine of anger, resentment, and backlash. Conversely, the importance of honest and objective judicial institutions has also been underscored, as has the importance of maintaining a distinction between revenge and justice. Moreover, officers and senior non-commissioned officers (NCOs) of the U.S. Army must realize that they may often have unique opportunities and unique credibility to offer advice on the lessons of Iraq to their counterparts in some of the Arab Spring nations. The U.S. Army has a long history of cooperating with some of the Arab Spring militaries and has a particularly strong relationship with the Egyptian military. These bonds of trust, cooperation, and teamwork can be used to convey a variety of messages beyond exclusively military issues.

All of the Arab Spring states may usefully consider the potential insights offered by events in Iraq, but the two Arab countries where the lessons of de-Ba’athification may be most relevant are Libya and Syria. Libya is currently organizing a post-Qadhafi government, while Syria is undergoing a process of revolution that seems increasingly difficult for the authorities to extinguish. In Libya, post-Qadhafi leaders are openly concerned about avoiding what they identify as the mistakes of Iraq. It remains to be seen if they are able to do so, or if they fall into new systems of internal warfare and perhaps new dictatorship. Syria maintains both a society and a style of rule that has notable similarities to the Saddam Hussein government. Its future is deeply problematic, as revolutionaries struggle against an entrenched, well-armed, and increasingly desperate dictatorial regime that is also deeply sectarian in nature.

There was a tendency among promoters of the [2003-2011 Iraq] war to believe that democracy was a default condition to which societies would revert once liberated from dictators.

Francis Fukuyama1

I pleaded with Bremer not to dissolve the [Iraqi] army, and warned him that it would blow up in our faces. I told him that I understood the rationale behind the process of de-Baathification, but that it needed to apply only to those at the top with blood on their hands….I said I hoped he understood that if he was going to de-Baathify across the board, he would be setting himself up for major resistance and would create a power vacuum that someone would have to fill.

King Abdullah II of Jordan2

You cannot build a country if you don’t have reconciliation and forgiveness.

Aref Ali Nayed

Libyan National Transitional Council

INTRODUCTION

[edit | edit source]The presence of U.S. combat troops in Iraq has now come to an end, and the lessons of that conflict, including those involving de-Ba’athification, will be debated for some time to come. De-Ba’athification for Iraq was initiated by U.S. policymakers in 2003 as the process of eliminating the ideology of the Iraqi Ba’ath Party from public life and removing its more influential adherents from the Iraqi political and administrative system. This policy constituted a central part of the effort to eliminate all significant aspects of the Saddamist state and remake Iraq into a democratic nation. It has also emerged as one of the most controversial aspects of U.S. post-war activities in Iraq. While supporters claim that the approach was unavoidable if Iraq was to be reformed, critics maintain that the approach, as practiced, amplified sectarian divisions in Iraq and also served as an important enabler of enhanced sectarianism and the post-invasion Iraqi insurgency.

U.S. Government decisionmaking about the nature and depth of the de-Ba’athification effort centered on the conflict between pragmatists who were attempting to prevent U.S. and Iraqi post-war authorities from losing their capacity to manage the emerging crisis in Iraq and various hardliners—often called neoconservatives—calling for a fundamental restructuring of Iraqi society. The dominant fear of the first group was that Iraq would degenerate into chaos without some effort to rehabilitate and retain those Ba’athist bureaucrats and officials not directly implicated in the Saddam Hussein regime’s crimes. For the second group, the primary concern appeared to be ensuring that a favorable outcome for regime change was permanent. Their greatest fear was often that a system of “Saddamism without Saddam” would dominate the post-war environment unless large-scale societal restructuring took place within Iraq.4 In both groups, there was a wide range of opinion, and some individuals (perhaps most prominently National Security Council [NSC] Advisor and later Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice) were open to the arguments of both sides and sought to synthesize them into coherent policy.

While de-Ba’athification still retains some defenders in the United States, most Middle Eastern politicians and observers consider it to have been deeply misguided, and many Arabs view it as a warning of the ways in which a transition from dictatorial rule can go wrong and lurch dangerously close to civil war. A strong exception to this belief can sometimes be found among Iraqi and other Arab Shi’ites, who basically approve of a policy that punishes Iraq’s Sunni Arab community from which Saddam drew most of his supporters and that suffered less than other Iraqi communities under the dictatorship. The future of Iraq as a cohesive and modernizing country remains uncertain, and it is unclear if that society can overcome simmering sectarian differences, which current approaches to de-Ba’athification continue to inflame. The ways in which Iraq deals with the legacy of de-Ba’athification, as well as ongoing policies for national reconciliation, will have a great deal to do with deciding the Iraq future. While Iraqis often dream of building a society as prosperous as the Arab Gulf states, the danger remains of an Iraqi society that looks more like Lebanon during its 14-year sectarian civil war.

The onset of the Arab Spring has revived a number of questions about the problems with de-Ba’athification. At the time of this writing, Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya have experienced Arab Spring popular uprisings in which long-standing dictators have been ousted. Syria is also experiencing a serious mass uprising led by brave and extremely committed revolutionaries struggling against an entrenched and ruthlessly tenacious dictatorship. None of these states has ever experienced a government as authoritarian as Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, although the Syrian dictatorship clearly comes the closest to the Saddamist model. All of these states face considerable difficulties in establishing legitimate and moderate post-revolutionary governments, and some face the danger of prolonged civil conflict. Lessons that can be gleaned from the Iraqi experience may therefore be especially important for their future.

Lessons of the Iraqi De-Ba'athification Program for Iraqi's Future and Arab Revolutions

[edit | edit source]by w. Andrew Terrill

THE BA’ATH PARTY AS AN INSTRUMENT OF SADDAM HUSSEIN’S DOMINATION OF IRAQ

[edit | edit source]In order to understand problems surrounding the effort to remove Ba’athism from Iraq, it is necessary to give some consideration to the central tenets of Ba’athism as a political ideology and then to examine the ways in which this ideology was applied and practiced within Iraq under Saddam Hussein. In undertaking this analysis, it is worthwhile to consider that a number of dictatorial regimes have used official ideologies to justify the power of a particular elite rather than to guide their actions. Some individuals within the ruling elite of such systems may view themselves as seeking to adjust their approaches to emerging problems by emphasizing those aspects of the ideology that seem most useful for addressing a given problem, while de-emphasizing those that are less useful. Such people remain ideologues despite their willingness to show a limited degree of flexibility. Others do not take the national ideology particularly seriously but value its supporting party infrastructure to justify and generate support for the decisions of the political leadership, regardless of how ideologically inconsistent those decisions may be. These people are political opportunists in ideological garb.

The Ba’ath movement was founded in the 1940s by two Syrian teachers, Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din Bi tar, and stressed Arab unity, socialism, and efforts to modernize the Arab World. The party, which emerged in its modern form in 1947, sought to unite all Arab states and to provide them with a set of modernizing principles to help them overcome problems with poverty and backwardness. The word Ba’ath means renaissance or rebirth in Arabic. The movement also sought to address the problems of the entire Arab World and was not to be confined to any individual country. Ba’athists throughout the Arab World were often viewed as committed Arab nationalists who were particularly devoted to the concept of a strong, unified Arab nation. Their slogan is, “One Arab nation with an eternal mission.”

Aflaq and Bitar met at the Sorbonne in Paris, France, in 1929 where both of them became especially interested in Western literature and philosophy with an emphasis on Marxism and socialism. This form of study was a fairly conventional approach for Arab students in France, since only the French communists and socialists showed much sympathy for Syrian independence within the political spectrum of Paris in the 1930s. Moreover, Marxism’s emphasis on modernization and scientific socialism appealed to the two men as they struggled for a solution to widespread Arab impoverishment and underdevelopment. The Ba’ath Party. Thus began as a secular organization seeking to modernize the Arab World in ways that were rooted in leftist, European political and social thought. Islam was not seen as a major part of this modernizing outlook. In this regard, Aflaq was not even a Muslim, having been raised as an Orthodox Christian.5 Batar was a Sunni Muslim and, like Aflaq, had no interest in religion as a basis for the state. Within the context of Ba’athist ideology, Islam was primarily viewed as part of the Arab heritage rather than a way to organize contemporary political life. Their outlook was correspondingly deeply secular.

Like Marxist-Leninist organizations, the Ba’ath Party sought to enter power through the actions of a revolutionary elite operating in a variety of states, including Iraq. In the 1950s and 1960s, these tactics caused the Ba’ath to compete with a number of other conspiratorial movements to infiltrate the military and other centers of state power. Subversion and coups seemed the only way in which to achieve power since contested elections were almost never held in any Arab country except perhaps Lebanon. Major emerging political trends throughout the Arab World included communist and Nasserite movements as well as the Ba’ath. Thus, to achieve power within the various Arab countries Ba’athists had to operate clandestinely as one of many secretive opposition movements dealing with government counterintelligence units and their own splinter groups. Despite these difficulties, Ba’athists seized power in Syria and Iraq in 1963.6 The Iraqi Ba’ath Party remained in power for less than a year but once again seized power in 1968 partially as a result of the maneuverings of a young revolutionary named Saddam Hussein. Additionally, the previous Iraqi government had been unable to provide significant help to the other Arab countries at war with Israel in June 1967. Iraqi Ba’athist leaders portrayed this failure as a form of treason, and made anti-Israeli invective a centerpiece of their rhetoric following their seizure of power.7

The Iraqi Ba’ath Party began its existence with a commitment that all party members should have a broad set of rights to elect officials and present their views in party forums. Unfortunately, this approach changed rapidly over time, and by 1964 Aflaq was complaining about the stratification of the party and the consolidation of power by a limited number of “active members” with influence that dramatically exceeded that of the rank and file. He stated that such an approach “was wholly out of keeping with the spirit of our party’s rules.”8 Nevertheless, the requirement for the Ba’ath Party to carry out its activities in secret until it seized power for the second time in 1968 remained a central part of Ba’ath organizational culture throughout the organization’s existence. During its underground years, the Ba’ath became increasingly hierarchical, secretive, and accustomed to violence as a political tool. These mindsets carried over to the years in power when such an approach was viewed as equally necessary to cope with real and imagined internal and foreign enemies. The Ba’ath leaders continued to see conspiracies against their government from a variety of sources including the Western powers and Israel. The failure of Iraq’s first Ba’ath government to remain in power more than a year underscored the looming danger of a countercoup.

Ba’athism appeared to have some problems establishing a popular base in the first years after the 1968 coup. Some Iraqi citizens appreciated Ba’ath ideology for its emphasis on modernity and its rejection of ethnic/sectarian divisions, tribalism, and religion as the basis for a modern state. Unfortunately, in both Iraq and Syria, these principles had a more insidious function as well, helping to serve as a smokescreen for the domination of one social group over the others in each country. Secular principles in Syria were used to mask the almost complete domination of Syrian society by the Alawite minority, which is usually identified as an offshoot of Shi’ite Islam. In Iraq, the Ba’athist regime was dominated by Sunni Muslims, especially from the areas around Tikrit. The initial leader of the 1968 Ba’ath revolution in Iraq was General Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr, but he was progressively eclipsed by his young cousin, the hard-working, pragmatic, intelligent, and ruthless Saddam Hussein.

Saddam Hussein emerged as the strongman behind the scenes of the regime by the early 1970s and replaced Bakr as president in July 1979. Although Saddam permitted some loyal Shi’ites to rise to high-profile positions in government and the military, the core of his support was composed of Sunni Arabs. Shi’ite political leadership was traditionally drawn from the Iraqi Communist Party, the al-Dawa Islamiya (Islamic Call) Party, and the Shi’ite clergy. Both the Iraqi Communist Party and the Dawa Party were outlawed by the Ba’athists, and their members were ruthlessly massacred during Saddam’s years in power. The Shi’ite clergy also faced massive repression under the Saddam Hussein regime, although the regime could not actually wipe them out without severe internal and regional repercussions. Instead, Saddam sought to silence the clerical leaders or force them to speak in favor of the regime. He also demanded that Sunni clerics adopt a nonpolitical role but never saw them as the same type of threat as the leading Shi’ite ayatollahs.

Saddam’s relationship with Ba’athism is complex. His ability to emerge as a key Ba’athist leader is directly attributable to party co-founder, Michel Aflaq, who befriended Saddam in exile after the younger man was forced to flee Iraq following his participation in an unsuccessful assassination attempt against Iraqi President Abdul Karim Qassim. During his years outside Iraq, Saddam was able to gain Aflaq’s patron age as a way to achieve high rank within the party. Saddam’s ongoing relationship with Aflaq was useful to him throughout his life. Unlike the Syrian Ba’ath Party, which ousted Aflaq and Bitar from power in February 1966, Saddam remained aware of the value of maintaining Aflaq as an honored but powerless member of the Iraqi leadership. Aflaq, for his part, had hoped to be a positive and moderating influence on Saddam once the dictator achieved power, but most of his suggestions on important issues were ignored. Saddam did flatter the older man by agreeing to some of his minor concerns. Such cosmetic concessions were an acceptable trade-off for the public support of one of Ba’athism’s co-founders. By consorting with the dictator, Aflaq allowed Saddam to exploit him and Ba’athism as window dressing for one of the world’s most oppressive regimes. Bitar, by contrast, spent the remainder of his life in Europe. Aflaq died in 1989 in Paris, and Saddam let it be known that he used his personal funds to build a suitable tomb for the co-founder of Ba’athism.

Saddam was not a military man, and as a youth was rejected for entry into the Iraqi military academy due to poor performance on his entrance examinations.9 Throughout his rise to power, Saddam was correspondingly wary of the danger of a military coup and used the Ba’ath Party to help him secure full control over the Army. This concern is easily understandable since coups were the traditional means of ousting an Iraqi leader once his enemies were able to organize against him. In establishing an iron grip over the military, Saddam made heavy use of Ba’athist political officers and frequently promoted cronies within the military over more qualified officers. Officers with particularly heroic reputations in the Iran-Iraq war, as well as brilliant planners, were quietly sidelined, since there was room for only one “military genius” in Saddam’s Iraq. Saddam understood the value of efficient officers during times of war, but tended to place these officers in less important positions when he no longer had an immediate need for them.

The Ba’ath Party was also useful to Saddam in other ways than simply controlling the military and providing an ideological veneer for the regime. The creation of the Saddam personality cult had nothing to do with original Ba’ath ideology, but it was administered and energized by Ba’ath Party activists. As Saddam Hussein consolidated his rule over Iraq, he consistently viewed the Ba’ath Party as an instrument of dictatorial power and social mobilization. He did not take its ideology and values seriously as principles for leadership, and individuals at the highest levels were noted for their public and ostentatiously blind loyalty to the President rather than their knowledge of Ba’athist principles and political thought. While many members of the top leadership were Sunni, this was not an absolute requirement. Proven Saddam loyalists included Shi’ites, Kurds, and various sects of Christians.10 If Saddam believed a subordinate was a proven and committed loyalist, he did not particularly care what that person’s sect or ethnicity was. On the other hand, Saddam often viewed his own family and Sunni Arabs from the Tikrit area as having a head start on loyalty.11 Saddam and his cronies also seemed to view Sunni Arabs as being more likely to remain loyal, because they were usually more hostile to the traditional enemy of Iran and were likely to fear a new Shi’ite government in which they could be viewed as accomplices in Saddam’s crimes. Consequently, the Sunni Arabs were disproportionately represented in the Ba’ath’s senior ranks and the regime’s security units.

Once in power, the Ba’ath Party did follow through on some of its modernization rhetoric. Saddam was committed to building a modern state, although he basically sought this goal primarily to improve the efficiency of the dictatorship rather than to benefit the Iraqi people. Consequently, serious and intense Ba’ath Party literacy drives did more than teach Iraqi citizens how to read.12 They also opened an intellectual pathway that allowed them to be more thoroughly bombarded with regime propaganda. Efforts to reduce the power of the tribes and to limit the role of religion in public life were similarly presented as modernization efforts, although their primary purpose was to further centralize power in Baghdad. Moreover, such policies could be reversed when they were no longer convenient to the regime, as occurred in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s when Saddam’s regime sought to encourage some increased religious devotion, so long as such sentiments were properly channeled into activities that the regime viewed as useful.13 Additionally, Saddam was also willing to work through tribal elements when it suited his purposes.

On the eve of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion, Saddam’s Iraq was a one of the most rigid totalitarian states in the world, with a privileged elite composed of military leaders and Ba’ath Party members, virtually all of whom were terrified of the leader.14 The Ba’ath Party had at least two million members at that time, with some estimates reaching 2.5 million. Nevertheless, membership in the senior ranks of the Ba’ath Party did not protect individuals from Saddam’s terror, which was applied to them to ensure that rival centers of power did not develop within the party.15 Saddam was particular wary of ambitious “overachievers” who might be interested in political advancement in ways that could eventually lead to the rise of political competitors. He was also deeply wary of those officials who began to appear too pious. Saddam further had an occasional need for visible Ba’athist victims to reinforce the determination of the remaining Ba’athists to show unquestioning obedience and subservience. Senior leaders such as Tariq Aziz were sometimes publicly embarrassed by Saddam, as when he was told to lose weight and had his weekly progress reported in the newspaper.16 More ominously, a casual joke about Saddam or his priorities could result in the loss of a senior leader’s tongue.17 Everyone within the Iraqi political leadership understood that they had no rights that Saddam could not immediately nullify if he chose to do so for whatever reason. This principle applied to the top elite as well as the oppressed masses. Thus, when Saddam was ousted in 2003, some Ba’athists as well as non-Ba’athists were open to the idea of participating in the building of a new Iraq if they had the opportunity. The most likely exceptions to this approach would be those Ba’athists who were implicated in Saddam’s crimes. These people knew there would never be any kind of future for them in an Iraq without Saddam or at least a Saddamist type of system.

THE DE-BA’ATHIFICATION ORDER OF MAY 16, 2003

[edit | edit source]Under the circumstances noted above, the Iraq population was confused and uncertain about what would happen to the Ba’athists once Saddam’s regime was removed from power. While General Tommy Franks had abolished the Ba’ath Party in a 2003 message to the Iraqi people, he gave little indication of how individual Ba’athists outside of Iraq’s top circles would be treated. In the immediate aftermath of Saddam’s ouster, both the U.S. military and the newly established Organization for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (ORHA) seemed to be showing some clear flexibility. ORHA was willing to allow former Ba’athist administrators and professionals such as doctors and professors to keep their jobs so long as they were not implicated in regime crimes and were willing to renounce their previous Ba’athist affiliations.18 This approach was viewed as necessary to keep the economy from further declining or even collapsing. The U.S. Army also showed considerable pragmatism by sponsoring renunciation ceremonies in which thousands of people burned their Ba’ath membership cards, renounced violence, and pledged to help build the new Iraq.19 This approach was particularly successful in the area around Mosul, where then Major General David Petraeus presided over such ceremonies. Mosul, at this time, remained quiet, despite its tradition of supplying large numbers of Sunni Arab officers to the Iraqi military. Later, after more comprehensive de-Ba’athification policies were instituted over the objection of the U.S. military leadership there, everything changed, Mosul became much more difficult to manage, and a strong al-Qaeda presence was established in the region.

As noted above, the more tolerant approach of ORHA was not to last. An order to de-Ba’athify Iraqi society was the first major official act of Ambassador L. Paul Bremer upon his arrival in that country to assume control of the newly created Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), which replaced ORHA. Bremer issued this order on May 16, 2003, after being provided with the directive in draft form by Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Douglas Feith. According to Bremer, Feith told him that such an order was absolutely essential to Iraq’s rehabilitation.20 The order disestablished the Ba’ath Party and removed members of the four highest ranks of the party from government positions. It also banned them from future employment in the public sector. Additionally, the order required that anyone holding positions in the top three management layers in government institutions be interviewed to determine their level of involvement with the Ba’ath Party as well as their possible involvement in criminal activities. Those determined to be senior members of the party were to be removed from their positions and banned from any future public employment. The order also called for the creation of a rewards program to pay individuals providing information leading to the capture of senior Ba’ath Party members.

The supporters of the de-Ba’athification program frequently maintained that this approach was inspired by the de-Nazification efforts that followed World War II in Germany. Iraqi exiles were fond of the term, which they may have viewed as loaded in a way that made it a useful public relations tool to advocate war and to help clear a way for prominent roles for themselves in the new Iraq. Additionally, some U.S. senior officials had, by this time, begun viewing Iraq through the lens of Nazi Germany with Saddam as Hitler and the Ba’ath Party as the Nazis.21 Such analogies correctly point out the moral repugnancy of the Saddam Hussein regime, but they also allow one to glance over the particulars of Iraqi society and argue about Iraq’s future on the basis of analogies rather than conditions within Iraq itself. In just one important difference, it may be significant that the Nazis rose to power as a large and powerful mass movement, whereas the Ba’athists rose to power in Iraq through the actions of a group of conspirators. Individuals joining the Ba’ath movement after it seized power may have done so with motives other than loyalty to Saddam Hussein.

The de-Ba’athification order and the subsequent CPA Order #2 (issued shortly afterward on May 23 to disband Iraq’s military and intelligence forces) reflect the priorities of both Under Secretary Feith and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz. These priorities centered on the destruction of all forces previously involved in supporting the old regime and particularly those forces that they believed had a chance of reconstituting that regime. The Ba’ath had a long history of underground activity as well as a past pattern of infiltrating key institutions and then attempting to seize power by illegal means. The revival of Ba’athism through conspiracy and intrigue therefore seemed a realistic danger. Unfortunately, such a revival was not the only serious danger facing Iraq at this time, and it was not clearly so dangerous as to trump all other security concerns. It is also not clear if the U.S. leadership fully understood the numbers of enemies that they were making by undertaking such policies or the backlash such actions could produce. The possibility that such a backlash could lead to a serious Sunni military challenge to the new Iraq was apparently dismissed on the grounds that such “dead-enders” were a marginalized force and would not be able to establish a popular rather than a conspiratorial movement within Iraqi society. Ahmad Hashim, in his insightful study of the Iraqi insurgency, quotes an anonymous U.S. policymaker as stating, “We underestimated their [the Iraqis] capacity to put up resistance. We underestimated the role of nationalism. And we overestimated the appeal of liberation [as trumping all other considerations for Iraqi political behavior].”22 Another even more biting critic stated that the civilians within the George Bush administration had made the fundamental mistake of confusing strategy with ideology.23

Some authors also claim that the CPA’s policies were deliberately anti-Sunni and pro-Shi’ite because of a belief within the Bush administration that Sunnis were more dangerous to U.S. interests, while Shi’ites were more likely to be grateful to the United States for ousting Saddam, since they had suffered more under his regime.24 This charge about administration policymaking is more popular in the Arab World than in the United States and is difficult to confirm. Some Bush policymakers did speak forcefully against Sunni control in Iraq, but they justified their concerns around the theme of democracy rather than the inherent untrustworthiness of the Sunni Arabs.25 In some regional media, as well as in Iraq, the de-Ba’athification policy was sometimes referred to as “de-Arabization.”26 The central tenets of the Ba’ath Party are Arab nationalism, anti-imperialism, and Arab socialism. Such ideals are not usually viewed as offensive by themselves, and many Arabs consider them to be noble and praiseworthy. Treating Ba’athism, instead of Saddam’s version of Ba’athism, as corrupt was therefore a problem for many Arabs and the pan-Arab media including the satellite television stations where Iraqis often sought to get the news.

In an effort that further complicated the situation, some leading Iraqi Shi’ites attempted to play upon U.S. fears by suggesting that Sunnis were “Arab nationalists.” This is a label that is seldom viewed as a slur in the Arab World, but in this instance was apparently used to suggest an anti-American and anti-Israeli worldview. Throughout the years following the invasion, some Shi’ite leaders consistently sought to convey the view that Sunnis were irredeemably wedded to radicalism, and needed to be marginalized to protect both Iraqi and Shi’ite interests. In one particularly revealing incident, Shi’ite leader Abdulaziz Hakim made it clear that he supported democracy so long as his organization and sect benefited from that democracy. In conversations reported by journalist Bob Woodward and others, Hakim told members of the Baker/Hamilton Iraq Study Group that the government of Iraq represented 80 percent of the population of that country (Shi’ites and Kurds) so democracy was served, and nothing had to be done about the remaining Sunnis.27

When Bremer informed the senior staff of the CPA (and especially the ORHA holdovers) of the new de-Ba’athification approach, he met immediate resistance over the scope of the order that he had brought from Washington. Retired Lieutenant General Jay Garner, the outgoing Director of ORHA, was reported to have been disturbed by the order, which he characterized as “too deep.”28 Charlie Sidell, the Baghdad Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Chief of Station who worked with Garner during this period, stated, “Well if you do this, you’re going to drive 30,000 to 50,000 Ba’athists underground by nightfall, and the number is closer to 50,000 than it is to 30,000.”29 Garner and Sidell went to Bremer to attempt to dissuade him from issuing the order until it had been moderated to reflect the realities that they were facing. They recommended eliminating the top two levels of Ba’athist leadership, which was about 6,000 people.30 According to Garner, Bremer stated, “Look, I have my orders. This is what I am doing.”31 Since Bremer held the rank of Presidential Envoy in direct communication with the President, it is not immediately clear who issued such orders. Undersecretary Feith could not have done so on his own authority. President Bush had previously given Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld managerial control of the occupation, so it is possible that Feith spoke for Rumsfeld who spoke for Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney.32 A complicating factor in this situation is that throughout his time in office, Bremer was willing to ignore the advice of the Defense and State Departments on other issues later in his tenure. If he did not do so in this instance, he probably believed in the policy that was being put forward or considered it to have come directly from the President. It is also likely that he did not fully understand the importance of the advice he was receiving from Garner and the CIA, since he later stated that he did not recall the conversation.33 Garner left Iraq shortly afterward, sharing his concerns over de-Ba’athification with U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) Deputy Commander then Lieutenant General John Abizaid, who also feared that the deep de-Ba’athification effort would feed the developing resistance.34 General Abizaid would become CENTCOM commander after General Franks’ retirement.

In a related event, President Bush later appeared to blame Bremer for disbanding the Iraqi Army (although not for deep de-Ba’athification), suggesting that presidential guidance on one of the most important issues of the occupation was not reflected in CPA decisionmaking. Rather, Bush told journalist Robert Draper, “The policy had been to keep the [Iraqi] army intact. Didn’t happen.”35 Bremer responded angrily to the President’s statement, saying that he had been ordered to disband the Army by Rumsfeld, and the White House had approved the move. He also made the unusual claim that disbanding the Iraqi Army had been the correct choice, but he was not the one responsible for this decision.36 Clearly, these are very different versions of the truth, and no one wants to take responsibility for disbanding Iraqi security forces in spite of Bremer’s professed belief that it had been the correct approach. Despite this inconsistency, Bremer’s arguments have a certain level of resonance, since it is difficult to believe that he would have implemented such dramatic policy changes without at least a general understanding of President Bush’s priorities on de-Ba’athification and the future of the Iraqi military.

At this point, Bremer was imposing Washington’s priorities and appeared primarily concerned about preventing the possible reconstitution of the Ba’ath regime. These fears may have been enhanced by Saddam’s status as a fugitive at that time. Moreover, Bremer also entered Iraq with the determination to establish himself quickly as a decisive leader willing to make decisions that were unpopular with his staff, the military, and others in the U.S. Government. In his book, Bremer relates an incident in which his son gave him a pair of desert combat boots as a going away gift with the note that they were to help him “kick some butt.”37 He was apparently in total agreement with that sentiment.38 Bremer clearly felt that asserting his will over subordinates was exceptionally important if he was to maintain effective control of the CPA and Iraqi policy.39 He made this effort in the face of considerable local unhappiness about CPA policy, and de-Ba’athification was especially unpopular in the U.S. military because U.S. officers lost their hardest working and most competent counterparts.40 In response to the order, some commanders, and most notably General Petraeus, sought wide authority to grant waivers from the de-Ba’athificaiton requirements for local individuals to limit the disruptions caused by this policy.41

Bremer claims in his book that he expected the de-Ba’athification order to be applied to only about 20,000 people, or what he identified as 1 percent of all party members. The program would therefore include the ranks officially designated as “Senior Party Members.” Bremer also claims to have been sensitive to the needs of lower-ranking Ba’ath Party members to join the organization to make a living. He later maintained that his order was applied in ways that he never intended, and that many more people were purged than he had envisioned under the original program. This included people of much lower rank than the levels of Ba’ath membership outlined in the order as well as individuals whose links to the Ba’ath Party leadership were tenuous at best. He was also apparently unresponsive to Ambassador Barbara Bodine’s argument made earlier to General Garner that some senior members of the party were not criminals, while various junior members had engaged in serious crimes, making a blanket approach based on rank alone unfair and ineffective.42

Another problem for the CPA was that the justice of the de-Ba’athification order was not clear to many Iraqis. Joining the Ba’ath Party in Saddam’s Iraq was a rational decision for anyone seeking to feed their family and live in conditions other than squalor and poverty. The best and most numerous jobs in Iraq are found in the government and in state-controlled enterprises such as the oil industry. In Iraq, as in most Middle Eastern countries, there is not a strong private sector with a wide variety of good jobs. Socialism and state control of the economy were official parts of the Ba’ath ideology, further weakening the nongovernmental sector, while years of United Nations (UN) sanctions (1990-2003) undermined foreign investment in the Iraqi economy and also retarded private sector development. Yet, it is also within the government that one was most vulnerable to pressure to show enthusiasm for Saddam’s rule. In this environment, the greatest and most direct system of rewards and punishment had been put into place for rewarding loyalty to the government and the party. In Iraq, a non-Ba’athist primary school teacher would usually be paid the equivalent of U.S. $4 per month, while a Ba’athist in the same position, doing the same work, would be paid around $200 per month.43

Unfortunately, Bremer’s estimate of 20,000 people being purged as a result of his order did not hold up. While exact numbers are impossible to obtain, most estimates place the number as at least 30,000 and possibly up to 50,000 individuals.44 A few estimates place it even higher and note that the party members’ families, as well as ousted Ba’athists, were harmed by the mass firings.45 Blanket de-Ba’athification punished Iraq’s managerial class merely for being part of that class, and not because of individual misconduct, abuse of power, or other crimes. Moreover, other choices were available to address the problem, although they clearly would have been more cumbersome. According to one observer, the best alternative would have been to place the Ba’athists on trial and then punish those found guilty of human rights violations, corruption, incompetence, and other crimes. A truth and reconciliation commission could then have been established along South African lines. Such an option would have avoided the approach of treating all Ba’athists in responsible positions as criminals.46 Additionally, there was also the possibility supported by Garner and others to dismiss only the top two levels of the Ba’ath Party leadership and thereby try to avoid plunging Iraq into an administrative vacuum by eliminating managers and technocrats, many of whom were only “nominal Ba’athists.”47

As will be examined later, Bremer maintains that his de-Ba’athification order was issued with a full understanding of the complexities of Iraqi society, but it was overzealously applied. Yet, if Bremer’s authority and the approach of his order were abused, he still cannot be fully absolved for the difficulties that followed. In addition to problems with the decision itself, it is unclear that the CPA leadership paid enough attention to how his order was being implemented throughout the process rather than simply issuing a fiat and expecting it to be carried forward without difficulty, first under the authority of the CPA and then by the Iraqi government. Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, a former commander in Iraq, excoriated the CPA on these grounds noting, “[T]he CPA treated [de-Ba’athification] like they were issuing an academic, theoretical paper. They simply released the order and declared success. But there was no vision, no concept, and in my opinion, no desire to ensure that the policy was properly implemented. On the other hand, it did look good on paper.”48

While Bremer was to become more pragmatic over time, his first few days in Iraq resulted in what have arguably emerged as some of the worst mistakes associated with the war, and these mistakes were impossible to reverse by the time he started to understand their negative implications.49 It is nevertheless also useful to understand the context of Bremer’s actions by looking at the reaction to these policies in Washington. In his memoir, Douglas Feith minimizes the chaos created by de-Ba’athification, and takes issue with Bremer’s later second thoughts about the policy.50 Unlike Bremer, he was unprepared to admit that the de-Ba’athification policy may have been producing bad results. Rather than adjust his focus to the real and emerging problems as Bremer eventually did, Feith, at least publicly, continued to support policies that were proving disastrous.

ADMINISTRATION OF THE DE-BA’ATHIFICATION PROGRAM

[edit | edit source]Nine days after the issuance of CPA Order Number 1, Bremer established a de-Ba’athification Council, which he was to supervise and which would report “directly and solely” to him.51 Later, on November 3, 2003, the responsibility for implementing de-Ba’athification was passed from the CPA to the U.S.-created Iraqi Governing Council (IGC).52 The IGC made de-Ba’athification the responsibility of Governing Council member Ahmad Chalabi, who was placed in charge of the newly-created “Supreme National Commission for De-Ba’athification.” Chalabi was supported in his efforts at deep de-Ba’athification by the Shi’ite religious parties such as Dawa and the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI, later the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq) and by various Kurdish groups. Former post-Saddam Defense Minister Ali Allawi (not to be confused with Ayad Allawi) describes Iraqi Kurds as favoring broad de-Ba’athification, but with so many exceptions that their actual priorities were difficult to sort out.53 Most Sunni Iraqi Arabs did not favor deep de-Ba’athification, al though many of them had also suffered under Saddam Hussein. Additionally, it did not escape Sunni Arab attention that the primary Iraqi champions of deep de-Ba’athification were formerly exiled Shi’ite politicians such as Ahmad Chalabi of the Iraqi National Congress and Abdul Azziz Hakim of SCIRI. Many Sunni Iraqi Arabs considered “de-Ba’athification” to be synonymous with “de-Sunnization,” a strong and deliberate effort to marginalize the role of the Sunni Arab community in Iraq’s political future.54

The de-Ba’athification process impacted every important aspect of Iraqi economic life, due to the centrality of state-run enterprises to the Iraqi economy. These included the educational system, utilities, food distribution centers, and the oil industry. The possibility that Ba’athists would be educating young people was of special concern to those in favor of deep de-Ba’athification. Consequently, the de-Ba’athification order was used to justify the immediate firing of 1,700 university professors and staff throughout Iraq, although no one maintained that they were all complicit in Saddam’s crimes or even that they were committed Ba’ath ideologues.55 Rather, they were often simply attempting to get by within the Saddamist system that permeated the state. The post-Saddam former prime minister Ayad Allawi has referred to this approach as Iraqi citizens using Ba’athist membership as a “vehicle to live.”56 Later, Bremer expressed unhappiness that “tens of thousands” of school teachers (K-12) had been dismissed from their jobs, even though they were only low-ranking members of the Ba’ath Party who had been forced to join as a condition of their employment.57 He strongly disapproved of such actions, but by this time much of the de-Ba’athification process had moved out of his direct control and was be ing managed by either Chalabi or by local committees that had set themselves up using Bremer’s order as the rationale for their activities. Chalabi, who had strong allies in the U.S. civilian leadership of the Pentagon, may have been particularly difficult for Bremer to moderate. Much later, in retrospect, Bremer indicated that de-Ba’athification should have been conducted by a judicial body rather than a commission led by Iraqi politicians.

The collapse of large segments of the Iraqi educational system harmed not only teachers but students and Iraqi families by rendering schools and universities increasingly dysfunctional. It also created pools of high school and college age males who could sometimes be approached about the possibility of participating in the insurgency. Other state-controlled bureaucracies were decapitated as well, but these leadership gaps did not always last for long. In the south and the Shi’ite sections of Baghdad, Shi’ite clergy and their supporters quickly established their leadership over a variety of local government institutions.59 Many of these people were affiliated with Muqtada Sadr’s Sadr II movement (so named to indicate continuity with his murdered father’s charitable activities). Holdover officials within the establishments seized by the Sadrists or other groups were quickly made to feel unwelcome or even in danger unless they pledged loyalty to the new leadership. These new political leaders often had no concept of the technical or administrative issues associated with the enterprises that they seized. Nevertheless, the rise of Shi’ite clerics to fill the political vacuum in their own community is not surprising. The Shi’ite political establishment was one of the only organized forces outside of the Ba’ath Party in Iraq at the time of the invasion. Moreover, it had a strong and loyal following, a system of self-financing, and a record of long-standing persecution by the regime. Later, the Sadrists lost some of their initial power following Muqtada Sadr’s political and military confrontations with the Iraq government led by rival Shi’ite politician Nuri al-Maliki.

Many Ba’athists who held ranks below the highest four levels of the Ba’ath Party were also purged under the 2003 de-Ba’athification order, because it was often difficult to discern an individual’s rank within the Ba’ath Party. Often such standing was not clear to those around the person, and a large number of records were destroyed in the immediate aftermath of the invasion and the looting of Iraqi government offices that occurred following the fall of the Saddam regime. Individuals who held important administrative positions were therefore often simply assumed to be high-ranking Ba’athists and removed from office. Ironically, some individuals who were not important in the Ba’ath Party were strong pro-Saddam sympathizers, while some important Ba’athists sought to rise within the Iraqi government and bureaucracy through whatever means available. Allowing junior officials to assume the jobs of their former superiors did not necessarily lead to a bureaucracy that was inherently more anti-Saddam or pro-democracy. The decision to place Chalabi in charge of the de-Ba’athification process was also unfortunate. At least some U.S. leaders were aware of exactly what they were getting with a Chalabi-led de-Ba’athification Commission, and they should have understood that he was not likely to show restraint on this issue.60 Chalabi had been an advocate for wide-ranging de-Ba’athification well before the war against Saddam had begun in 2003. He had previously published his concerns that the United States would invade Iraq but would not attempt to eliminate all aspects of the Ba’ath Party with the comprehensiveness that he favored. In a February 19, 2002, Wall Street Journal editorial, Chalabi attacked what he called the plans for the future occupation of Iraq, which he apparently believed he understood on the basis of testimony before Congress by U.S. military and Bush administration officials. According to Chalabi, “[T]he proposed U.S. occupation and military administration of Iraq is unworkable. Unworkable because it is predicated on keeping Saddam’s existing structures of government in place—albeit under American officers.”61 He went on to claim that, “Iraq needs a comprehensive program of de-Ba’athification even more extensive than the de-Nazification effort in Germany after World War II.”

Chalabi has often been identified as the least popular member of the Governing Council among the Iraqi population at the time of his appointment by the IGC to head the de-Ba’athification Commission. His status as an exile caused at least some to view him as an outsider who had no experiences of the challenge of living under Saddam.62 The strong and public ties Chalabi held to both Israelis and pro-Israeli figures in the U.S. Government were well-known and not universally appreciated throughout Iraq.63 Later, the December 2005 elections underscored his unpopularity when his political party failed to win a single seat in the 475-person Parliament, despite a massive political campaign under the slogan, “We Liberated Iraq.”64 The decision to move forward with Chalabi at the head of the Commission rather than seeking a more reconciliation-oriented figure indicated a continuing determination to impose a harsh peace on the Sunnis and anyone associated with the old regime. This approach was consistent with the priorities of the senior Pentagon civilians who remained concerned that a regime similar to the one led by Saddam could reemerge. This danger was also worrisome to many of Iraq’s Shi’ite and Kurdish leaders who were aware that the Ba’ath had previously come to power twice through coups.

As noted, the Shi’ite religious parties and other community leaders were among the groups most interested in comprehensive de-Ba’athification priorities. U.S. policymakers seeking to justify a more sweeping de-Ba’athification policy were quick to point out that failure to do this would potentially harm U.S. relations with these parties.65 Nor is it difficult to understand the intense hatred Shi’ites and Kurds held for Saddam and the Ba’ath. Shi’ite religious parties, as well as the Shi’ite-dominated Iraqi Communist Party, had suffered intensively under Saddam, and most prominent members of these organizations had lost a number of friends and family members to torture and execution by the regime. The rise of a Shi’ite Islamic republic in Iran through revolution was particularly frightening to Saddam, who unleashed an especially high level of brutality against Iraqi Shi’ites who seemed even the slightest bit comfortable with the Iranian concept of Islamic government. An overly political definition of Shi’ite identity during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war was especially dangerous. Nevertheless, revenge (or justice) was not the only motivation for the Shi’ite parties in supporting de-Ba’athification. Many of these groups also wanted as much power as possible for themselves. Destroying the political viability of the Sunni leadership in Iraq helped to move them toward that goal. Some Shi’ite leaders may have also hoped to reverse the situations of Sunnis and Shi’ites permanently. In contrast to Iraq’s first 8 decades of existence, Shi’ites would hold the important positions, and Sunnis would be politically marginalized. Under these circumstances, some Sunni Arabs believed that they were being offered second-class citizenship at best.

The CPA de-Ba’athification order was sometimes taken as at least a partial green light for some Iraqis to exact revenge on former Ba’athists who had persecuted them or were their personal enemies. Indeed, a Shi’ite assassination campaign against former Ba’athists did take place, although it is doubtful that a more reconciliationist approach by the CPA would have prevented these outbreaks of violence, once the dictatorship had been removed. 66 Many of these assassinations were carried forward in a highly professional manner, rather than as frenzy or sloppy revenge attacks. It is correspondingly possible, if not likely, that Iranian intelligence units coordinated with friendly Shi’ite groups to ensure that Ba’athist enemies of Tehran were never in a position for them to cause trouble for Iran again.67 According to the London-based newsmagazine, The Middle East, Iranian Supreme leader Ali Khamenei put the commander of the al-Quds Force in charge of setting up a network of covert operatives in Iraq as early as September 2002, with the mission of expanding Iranian influence in that country in the aftermath of the invasion.68 If Chalabi hoped to use the de-Ba’athification Commission as an avenue for his own rise to power, he was deeply disappointed by the outcome of the 2005 election. While he may have helped to create a power vacuum by purging a number of potential rivals, he did not have the ability to fill it through the electoral process. Rather, the most important players in Iraq at this stage were quickly proven to be the Shi’ite religious parties who were also enthusiastic supporters of de-Ba’athification. After the election, Chalabi moved in and out of a variety of governmental jobs, which he held for various lengths of time. Throughout his political maneuvering, he was unable to obtain real power within the top leadership of the government.

As noted above, many Iraqi Sunnis viewed the effort to remove large numbers of Sunni leaders and bureaucrats from power through the vehicle of de-Ba’athification as part of a new political system in which Shi’ites would dominate Sunnis. The politicization of sectarian differences also led Iraqi political parties to adapt an approach whereby they viewed failing to fill a political post with one of your supporters or allies as tantamount to allowing that post to be filled by enemies.69 In addition to Sunni Muslims, some “establishment Shi’ites” had also risen to high ranks within the Ba’ath Party and were also caught up in de-Ba’athification. A key problem here is that Saddam actively reached out to secular Shi’ites to serve as “democratic ornaments,” while attempting to marginalize the Shi’ite clergy, which he felt was at least potentially loyal to Iran. 70 Some secular Shi’ite leaders, including those with advanced degrees from Western universities, took the bait for a variety of reasons including the hope that they could gain some reasonable level of patronage for their own communities. Some of these people were also well-educated and talented enough to be of real use to the regime in performing administrative tasks. These links with the regime allowed such individuals to become targets for de-Ba’athification in ways that the more persecuted opposition clerics did not once the regime had been removed.71

The most prominent example of the problems faced by “establishment Shi’ites” was the case of Saadoun Hammadi, the former Iraqi premier who died of leukemia in Germany in March 2007.72 Saadoun Hammadi had previously served as Iraq’s Foreign Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, Prime Minister, and most recently, Saddam’s last Speaker of the Assembly, thus becoming the highest ranking Shi’ite within the regime. Hammadi held a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Wisconsin and has been described as having a “thoughtful and scholarly demeanor.”73 He also is the author of a number of academic articles on Arab affairs and political philosophy.74 Hammadi favored economic and political liberalism in the past, and was presented to the world as a reform prime minister after the 1991 Gulf War. He apparently took his reform charter a little too seriously for Saddam and was removed for overzealousness after 7 months in power.75

As an articulate, respected Shi’ite intellectual who held high-profile/high-prestige government positions, Hammadi helped give Saddam’s government the appearance of broad-based Iraqi support across religious sects. Saddam thus presented Hammadi with the option of being co-opted and in return gaining a few crumbs of power for himself and some economic assistance for his Shi’ite supporters. This Faustian bargain was occasionally made available to Western-educated secular intellectuals, but it was almost never an option for important members of the Shi’ite clergy. Although Saddam sometimes sought to appear religious, formal clerical participation in the Ba’athist government was largely unacceptable to him. Certainly, no ayatollah would hold any of the governmental positions Hammadi held. Hammadi was arrested and placed in prison shortly after the U.S.-led invasion, while his son and members of his al-Karakshah tribe stringently protested his arrest on grounds that he did not take part in any crime against the Iraqi people.76 He was released in February 2004, in partial response to the uproar within the Shi’ite community. He then traveled to a series of Arab countries and then to Germany where he died.

Other secular Shi’ite leaders were also tarnished by their association with Saddam’s government, although they collaborated for a mix of personal, communal, and national motives. They were, however, not always subject to the same level of punishment as Sunni Ba’athists. According to the International Crisis Group (ICG), Shi’ite political parties involved with the de-Ba’athification process often allowed Shi’ite Ba’ath Party members to repent and keep their jobs. In doing so, the former Ba’athists became subservient to the parties that allowed them to remain in their positions and vulnerable to pressure from these parties so long as they remained a relevant political force.77 Any former Ba’athists showing much independence from the new political leadership at this stage usually found themselves accused of leaking information to terrorists or a variety of other crimes, regardless of whether or not they had done anything wrong. De-Ba’athification consequently may have helped the Shi’ite clergy and religious parties establish almost full control over the Shi’ite community during the first years following the invasion. While Shi’ite secularists, including those associated with the Ba’ath, were not punished to the extent of Sunni Ba’athists under de-Ba’athification, they were also not in a position to seek the leadership of the Shi’ite community. At this time, there seemed to be limited room for a reformed anti-Iranian secularist leadership that included ex-Ba’athists in Iraq.78

The removal of Ba’athist officials also created problems in finding suitable replacements with satisfactory political credentials. Some individuals who had been fired by Ba’athists from various bureaucracies under the Ba’athist regime became strong candidates to replace them following the change of regime. The problem here is that such individuals sometimes (perhaps often) were fired for nonpolitical reasons, including incompetence and corruption. Upon being returned to their former jobs or those of their former supervisors, they returned to old patterns of behavior, showing little responsibility, effectiveness, or commitment to even a limited work ethic. To be fair, it might be noted that these people had no monopoly on the shortcomings noted here. Most Iraqis had never had any preparation to work in an efficient, modernizing bureaucracy, and corruption permeated the society during the Saddam years as it still does.79

At various times, the Iraqi government announced that it was relaxing the de-Ba’athificiation policy, often as a response to U.S. pressure. Chalabi would usually announce the policy “changes” and then provide grandiose projections of how many people would be rehabilitated under new more lenient rules. In early 2007, for instance, he publicly agreed to soften the de-Ba’athification policy, announcing that his office had begun removing hiring restrictions from former Ba’athists who had not committed crimes during the Saddam years. Elaborating on this change, he stated that more than 2,300 former high-ranking Ba’ath Party members were either being reinstated in their former jobs or granted pensions.80 On the same day, Chalabi stated that over 700 former Ba’athists had returned to their old government jobs, suggesting that the balance of the 2,300 people he cited were given pensions if his figures are correct.81 Chalabi’s commitment to reform nevertheless remained tactical, and there is no independent evidence for the figures he cited. Additional ly, Chalabi opposed any new law on de-Ba’athification that would contain a sunset clause that would abolish the commission at some future point.82

An interesting window into the impartiality of the de-Ba’athification process occurred with the August 2008 arrest of Ali Faisal al-Lami, then the executive director of the de-Ba’athification Commission. Al-Lami was arrested as he returned home from Lebanon as a “suspected senior special group leader,” according to journalistic sources.83 Various offshoots of Muqtada al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army and other pro-Iranian terrorist organizations are known as “special groups” and are among the most extreme forces within the Iraqi political system. Some of these groups are controlled by Iranian intelligence organizations such as the al-Quds Force.84 The idea that someone comfortable with this ideology was presiding over de-Ba’athification is bone-chilling. Chalabi nevertheless demanded al-Lami’s release following the arrest.85 He stated that al-Lami played “a great essential role [in] fighting and confronting Saddam’s regime despite the risks that surrounded him.”86 He further added that U.S. forces pay “no attention to Iraqi human rights.” While many details of this situation were not disclosed and al-Lami’s guilt remained publicly unproven, his purported admiration for Tehran further reinforced the image of the de-Ba’athification Commission as hopelessly biased against Sunni Arabs. Al-Lami remained in detention until August 2009, when he was released as part of an agreement between the Iraqi government and various Shi’ite parties.87 After his release, al-Lami returned to political and de-Ba’athification activities, as noted later in this monograph. Al-Lami’s role in de-Ba’athification ended in May 2011 when he was assassinated by unknown gunmen who were probably members of al-Qaeda.88

MILITARY IMPLICATIONS OF DE-BA’ATHIFICATION

[edit | edit source]The decision to dissolve the Iraqi Army and the Ba’ath Party within the first few days of establishing the CPA administered an overwhelming blow to organized Iraqi life. This radical shock therapy was deemed by some members of the Bush administration as vital to the establishment of a stable democracy in Iraq. Of all of the CPA actions in this time frame, the abolition of the Iraqi Army was the most controversial and disconcerting to many Iraqis, who often viewed the military as something more than a pillar of the Saddam Hussein regime. Supporters of the decision often claim that the Iraqi Army dissolved itself, and that the reality of the post-war situation was simply being recognized. This argument implies that the United States only had only two choices, reconstituting the 600,000-man Iraqi Army in its Saddamist form or bringing the Iraqi Army down to zero. The choice, however, was never that binary, and the CPA order was issued at a point when U.S. Army General David D. McKiernan and various CIA officials were already working on a third option, that of reconstituting certain units of the Iraqi military on a voluntary basis under vetted officers.89 These efforts had to be discontinued following the CPA announcement.

Armed resistance to U.S. forces at some level following the invasion was probably inevitable, no matter how well the post-war reconstruction effort was handled. The question was, would this resistance comprise small groups of terrorists or would it encompass much larger forces drawn from alienated social groups that were able to organize into a strong network of resistance organizations. At this stage in the conflict, the Bush administration was loath to admit that segments of the Iraqi population were waging war against U.S. forces rather than welcoming them. At a June 2003 press conference, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld stated, “I guess the reason I don’t use the phrase ‘guerrilla war’ is because there isn’t one.”90 In general, the administration seemed to believe that the Iraqis would be sufficiently grateful for liberation that they would be granted sweeping ability to do anything they wanted in Iraq without much of a backlash.91 This view was emphatically reinforced by some of the most pro-war Iraqi exiles who maintained that Iraqis were so oppressed that they did not care about much else other than their deliverance from Saddam Hussein.92

The de-Ba’athification order, as unpopular as it was with Sunni Arab Iraqis, was not as unpopular as the disbanding of the Iraqi Army. Yet, if the United States was determined to implement a de-Ba’athification order, the rationale for dissolving the Army becomes much less clear. Senior Ba’athist officers could have been retired under the de-Ba’athification order, and low-ranking Ba’athists and non-Ba’athists could have been offered the option to remain in the military provided that they were not complicit in regime crimes. Ba’ath political officers, who were often resented by regular army officers, could easily have been removed from service, and elite units with special loyalty to Saddam could have been dissolved.93 The Iraqi Army under new leadership could then have been used to help provide order rather than be left disgraced with many of its members facing destitution. The special relationship of the Iraqi Army to Iraqi society went far beyond Saddam. Even a number of anti-Saddam Iraqi exiles urged that it not be abolished.94

The alternative to abolishing the Army in addition to wide-ranging de-Ba’athification would have been to purge and restructure the Army. This would involve removing the political functionaries and special security forces that served throughout the military to ensure loyalty to Saddam’s regime. The special security forces involved in this effort were commanded by Saddam’s younger son, Qusay, and were given sweeping powers to meddle in the operations of military units despite their lack of competence in military matters. The political officials were generally detested by the professional military, who would have welcomed efforts to rid the Army of such officials.95 Most would also have been pleased to end the long hours of ideological instruction that were supposed to support morale and readiness, but in effect detracted from unit preparation for military missions. The presence of these political units, the use of purges, and the general distrust Saddam felt for any gifted military leaders often caused many Iraqi Army officers to feel that they were victims of the regime rather than a part of it. It was, therefore, a deep shock to such individuals when the order was issued to disband them including those units that had chosen not to fight against the U.S.-led invasion.

Additionally, Saddam’s primary means of control over the military was the Ba’ath Party functionaries (“commissars”) noted above rather than insisting that all high-ranking officers join the Ba’ath. According to Colonel John Agoglia who served as a CENTCOM planner during this time frame:

[I]n June, we found the personnel records of the Iraqi Army at the Ministry of Defense, and we had those computers that contained those personnel records examined by special technical experts. The special technical experts confirmed in fact that the records were authentic and not tampered with. One of the key findings of those records which was shared with [CPA Director for National Security and Defense] Mr. [Walter] Slocombe, was that in fact you did not have large-scale Ba’ath issues in the army until you got to the major general rank, and at the major general rank, 50 percent of the major generals were Ba’athists and 50 percent weren’t.96

An important caveat is in order here, since the Iraqi Army was extremely top heavy and had more than 10,000 generals.97 Nevertheless, the database that Colonel Agoglia mentions could have been an invaluable tool in reconstituting the Iraqi Army and then using it to help provide security for the new government. This effort would have to include extensive use of other intelligence means to confirm all aspects of the database to the greatest extent possible.