Saylor.org's Ancient Civilizations of the World/The Prophet Muhammad

Overview

[edit | edit source]

The prophet Muhammad (c. 570-632 CE) was a religious and political leader from Mecca who united the pagan Arabians under one religious polity of Islam. Muhammad is considered by Muslims to be a prophet of Allah (God) as well as the last prophet to be sent by God. While he is widely considered the founder of the Islamic faith, Muslims prefer to think of him as a restorer of an uncorrupted version of the same monotheistic tradition of the Jews and Christians (the religion of Abraham). The revelations Muhammad reportedly received from Allah make up the text of the holy book of Islam, the Quran.

An orphan raised by his uncle, Muhammad grew up to work as as a merchant and shepherd. He was known to seclude himself for days at a time in a cave in order to pray in peace and after one such retreat at the age of 40, he returned stating that he had revealed his first revelation from God. Three years later, Muhammad began to publicly preach the messages he believed God had sent him, however the initial response from the pagans of Mecca was largely hostile. In 622, Muhammad fled this hostility in Mecca to the city of Medina in an event known as the Hijra. From Medina, Muhammad united many tribes and converted them to his new religion. In 630, he led his followers, now numbering roughly 10,000, to conquer Mecca and root out the paganism from the city.

Sources

[edit | edit source]Quran

[edit | edit source]

The Quran is the central religious text of Islam and Muslims believe that it represents the words of God revealed to Muhammad through the archangel Gabriel. Although it mentions Muhammad directly only four times, there are verses which can be interpreted as allusions to Muhammad's life. The Quran however provides little assistance for a chronological biography of Muhammad, and many of the utterances recorded in it lack historical context.

Early biographies

[edit | edit source]Next in importance are historical works by writers of the 2nd and 3rd centuries of the Muslim era (A.H. -- 8th and 9th century C.E.). These include the traditional Muslim biographies of Muhammad (the sira literature), which provide further information on Muhammad's life.

The earliest surviving written sira (biographies of Muhammad and quotes attributed to him) is Ibn Ishaq's Life of God's Messenger written ca. 767 CE (150 AH). The work is lost, but was used verbatim at great length by Ibn Hisham and later by Al-Tabari in hisTarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk (History of the Prophets and Kings). Another early source is the History of Muhammad's campaigns by al-Waqidi (d. 207 A.H.), and the work of his secretary Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi (d. 230 A.H.), Kitab Tabaqat Al-Kubra (The book of the Major Classes).

Many scholars accept the accuracy of the earliest biographies, though their correctness is unascertainable. Recent studies have led scholars to distinguish between the traditions touching legal matters and the purely historical ones. In the former sphere, traditions could have been subject to invention while in the latter sphere, aside from exceptional cases, the material may have been only subject to "tendential shaping".

Hadith

[edit | edit source]In addition, traditions regarding the life of Muhammad and the early history of Islam were passed down both orally and written for more than a hundred years after the death of Muhammad in 632. According to Muslims, the collection of hadith or sayings by or about the prophet Muhammad was a meticulous and thorough process that began right at the time of Muhammad. Needless to say hadith collection (even in the written form) began very early on – from the time of Muhammad and continued through the centuries that followed. Thus, Muslims reject any collections that are not robust in withstanding the tests of authenticity per the standards of hadith studies.

Western academics view the hadith collections with caution as accurate historical sources.Scholars such as Prof. Wilferd Madelung do not reject the narrations which have been compiled in later periods, but judge them in the context of history and on the basis of their compatibility with the events and figures.

Non-Arabic sources

[edit | edit source]The earliest documented Christian knowledge of Muhammad stems from Byzantine sources. They indicate that both Jews and Christians saw Muhammad as a "false prophet". In the Doctrina Jacobi nuper baptizati of 634, Muhammad is portrayed as being "deceiving[,] for do prophets come with sword and chariot?, [...] you will discover nothing true from the said prophet except human bloodshed." Another Greek source for Muhammad is the 9th-century writer Theophanes and his Chronicle . The earliest Syriac source is the 7th-century writer John bar Penkaye.

Life

[edit | edit source]Childhood and early life

[edit | edit source]Muhammad was born about the year 570 CE and his birthday is usually celebrated by Muslims in the month of Rabi' al-awwal. He belonged to the Banu Hashim clan, one of the prominent families of Mecca, although it seems not to have been prosperous during Muhammad's early lifetime.

His father, Abdullah, died almost six months before Muhammad was born. According to Islamic tradition, soon after Muhammad's birth he was sent to live with a Bedouin family in the desert, as the desert life was considered healthier for infants. Muhammad stayed with his foster-mother, Halimah bint Abi Dhuayb, and her husband until he was two years old. At the age of six, Muhammad lost his biological mother Amina to illness and he became fully orphaned. For the next two years, he was under the guardianship of his paternal grandfather Abd al-Muttalib, but when Muhammad was eight, his grandfather also died. He then came under the care of his uncle Abu Talib, the new leader of Banu Hashim. According to Islamic historian William Watt, because of the general disregard of the guardians in taking care of weak members of the tribes in Mecca in the 6th century, "Muhammad's guardians saw that he did not starve to death, but it was hard for them to do more for him, especially as the fortunes of the clan of Hashim seem to have been declining at that time."

While still in his teens, Muhammad accompanied his uncle on trading journeys to Syria gaining experience in commercial trade, the only career open to Muhammad as an orphan. Islamic tradition states that when Muhammad was either nine or twelve while accompanying the Meccans' caravan to Syria, he met a Christian monk or hermit named Bahira who is said to have foreseen Muhammed's career as a prophet of God.

Little is known of Muhammad during his later youth, and from the fragmentary information that is available, it is difficult to separate history from legend. It is known that he became a merchant and "was involved in trade between the Indian ocean and the Mediterranean Sea." Due to his upright character he acquired the nickname "al-Amin" (الامين), meaning "faithful, trustworthy" and "al-Sadiq" meaning "truthful" and was sought out as an impartial arbitrator. His reputation attracted a proposal in 595 from Khadijah, a 40-year-old widow who was 15 years older than he. Muhammad consented to the marriage, which by all accounts was a happy one.

Several years later, Muhammad was involved with a well-known story about setting the Black Stone in place in the wall of the Kaaba in 605 C.E. The Black Stone, a sacred object, had been removed to facilitate renovations to the Kaaba. The leaders of Mecca could not agree on which clan should have the honour of setting the Black Stone back in its place. They agreed to wait for the next man to come through the gate and ask him to choose. That man was the 35-year-old Muhammad, five years before his first revelation. He asked for a cloth and put the Black Stone in its center. The clan leaders held the corners of the cloth and together carried the Black Stone to the right spot, then Muhammad set the stone in place, satisfying the honour of all.

Beginnings of the Quran

[edit | edit source]

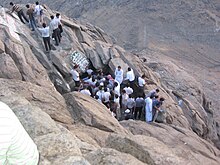

Muhammad adopted the practice of praying alone for several weeks every year in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca. Islamic tradition holds that during one of his visits to Mount Hira, the angel Gabriel appeared to him in the year 610 and commanded Muhammad to recite the following verses:

- Proclaim! (or read!) in the name of thy Lord and Cherisher, Who created-

- Created man, out of a (mere) clot of congealed blood:

- Proclaim! And thy Lord is Most Bountiful,-

- He Who taught (the use of) the pen,-

- Taught man that which he knew not.

- —Quran, sura 96 (Al-Alaq), ayat 1-5.

After returning home, Muhammad was consoled and reassured by Khadijah and her Christian cousin, Waraqah ibn Nawfal. Upon receiving his first revelations, he was deeply distressed and resolved to commit suicide. He also feared that others would dismiss his claims as being possessed. Shi'a tradition maintains that Muhammad was neither surprised nor frightened at the appearance of Gabriel but rather welcomed him as if he had been expecting him. The initial revelation was followed by a pause of three years during which Muhammad further gave himself to prayers and spiritual practices. When the revelations resumed he was reassured and commanded to begin preaching: "Thy Guardian-Lord hath not forsaken thee, nor is He displeased."

Muslim scholar Sahih Bukhari depicted Muhammad describing the revelations as, "Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell" and one of Muhammad's wives, Aisha, reported, "I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)". According to Prof. Alford T. Welch, these revelations were accompanied by mysterious seizures, and the reports are unlikely to have been forged by later Muslims. According to the Quran, one of the main roles of Muhammad was to warn the unbelievers of their eschatological punishment (Quran 38:70, Quran 6:19). Sometimes the Quran does not explicitly refer to the Judgment day but provides examples from the history of some extinct communities and warns Muhammad's contemporaries of similar calamities (Quran 41:13–16).

Muhammad was not only a warner to those who reject God's revelation, but also a bearer of good news for those who abandon evil, listen to the divine word and serve God. Muhammad's mission also involved preaching monotheism. The key themes of the early Quranic verses included the responsibility of man towards his creator; the resurrection of dead, God's final judgment followed by vivid descriptions of the tortures in hell and pleasures in Paradise; and the signs of God in all aspects of life. Religious duties required of the believers at this time were few: belief in God, asking for forgiveness of sins, offering frequent prayers, assisting others particularly those in need, rejecting cheating and the love of wealth (considered to be significant in the commercial life of Mecca), being chaste and not to kill newborn girls.

Opposition

[edit | edit source]According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife Khadija was the first to believe he was a prophet. She was soon followed by Muhammad's ten-year-old cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, close friend Abu Bakr, and adopted son Zaid. Around 613, Muhammad began his public preaching (Quran 26:214). Most Meccans ignored him and mocked him, while a few others became his followers. There were three main groups of early converts to Islam: younger brothers and sons of great merchants; people who had fallen out of the first rank in their tribe or failed to attain it; and the weak, mostly unprotected foreigners.

According to Ibn Sad, the opposition in Mecca started when Muhammad delivered verses that condemned idol worship and the Meccan forefathers who engaged in polytheism. However, the Quranic exegesis maintains that it began as soon as Muhammad started public preaching. As the number of followers increased, he became a threat to the local tribes and the rulers of the city, whose wealth rested upon the Kaaba, the focal point of Meccan religious life, which Muhammad threatened to overthrow. Muhammad’s denunciation of the Meccan traditional religion was especially offensive to his own tribe, as they were the guardians of the Ka'aba. The powerful merchants tried to convince Muhammad to abandon his preaching by offering him admission into the inner circle of merchants, and establishing his position therein by an advantageous marriage. However, he refused.

Tradition records at great length the persecution and ill-treatment of Muhammad and his followers. Sumayyah bint Khabbab, a slave of a prominent Meccan leader Abu Jahl, is famous as the first martyr of Islam, having been killed with a spear by her master when she refused to give up her faith. Bilal, another Muslim slave, was tortured by Umayyah ibn Khalaf who placed a heavy rock on his chest to force his conversion.

In 615, some of Muhammad's followers emigrated to the Ethiopian Aksumite Empire and founded a small colony there under the protection of the Christian Ethiopian emperor Aṣḥama ibn Abjar. Muhammad desperately hoping for an accommodation with his tribe, either from fear or in the hope of succeeding more readily in this way, pronounced a verse acknowledging the existence of three Meccan goddesses considered to be the daughters of Allah, and appealing for their intercession. Muhammad later retracted the verses at the behest of Gabriel, claiming that the verses were whispered by the devil himself. This episode known as "The Story of the Cranes" is also known as "Satanic Verses". Some scholars argued against its historicity on various grounds. While this incident got widespread acceptance by early Muslims, strong objections to it were raised starting from the 10th century, on theological grounds. The objections continued to be raised to the point where the rejection of the historicity of the incident eventually became the only acceptable orthodox Muslim position.

In 617, the leaders of Makhzum and Banu Abd-Shams, two important Quraysh clans, declared a public boycott against Banu Hashim, their commercial rival, to pressure it into withdrawing its protection of Muhammad. The boycott lasted three years but eventually collapsed as it failed in its objective. During this, Muhammad was only able to preach during the holy pilgrimage months in which all hostilities between Arabs were suspended.

Isra and Mi'raj

[edit | edit source]

Islamic tradition relates that in 620, Muhammad experienced the Isra and Mi'raj, a miraculous journey said to have occurred with the angel Gabriel in one night. In the first part of the journey, the Isra, he is said to have traveled from Mecca on a winged steed (Buraq) to "the farthest mosque," which Muslims usually identify with the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. In the second part, the Mi'raj, Muhammad is said to have toured heaven and hell, and spoken with earlier prophets, such as Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. Ibn Ishaq, author of the first biography of Muhammad, presents this event as a spiritual experience whereas later historians like Al-Tabari and Ibn Kathir present it as a physical journey.

Some western scholars of Islam hold that the oldest Muslim tradition identified the journey as one traveled through the heavens from the sacred enclosure at Mecca to the celestial al-Baytu l-Maʿmur (heavenly prototype of the Kaaba); but later tradition identified Muhammad's journey as having been from Mecca to Jerusalem.

Last years in Mecca before Hijra

[edit | edit source]Muhammad's wife Khadijah and his uncle Abu Talib both died in 619, the year thus being known as the "year of sorrow". With the death of Abu Talib, the leadership of the Banu Hashim clan was passed to Abu Lahab, an inveterate enemy of Muhammad. Soon afterwards, Abu Lahab withdrew the clan's protection from Muhammad. This placed Muhammad in danger of death since the withdrawal of clan protection implied that the blood revenge for his killing would not be exacted. Muhammad then visited Ta'if, another important city in Arabia, and tried to find a protector for himself there, but his effort failed and further brought him into physical danger. Muhammad was forced to return to Mecca. A Meccan man named Mut'im b. Adi (and the protection of the tribe of Banu Nawfal) made it possible for him safely to re-enter his native city.

Many people were visiting Mecca on business or as pilgrims to the Kaaba. Muhammad took this opportunity to look for a new home for himself and his followers. After several unsuccessful negotiations, he found hope with some men from Yathrib (later called Medina). The Arab population of Yathrib were familiar with monotheism and prepared for the appearance of a prophet because a Jewish community existed there. They also hoped by the means of Muhammad and the new faith to gain supremacy over Mecca, as they were jealous of its importance as the place of pilgrimage. Converts to Islam came from nearly all Arab tribes in Medina, such that by June of the subsequent year there were seventy-five Muslims coming to Mecca for pilgrimage and to meet Muhammad. Meeting him secretly by night, the group made what was known as the Second Pledge of al-`Aqaba, or the Pledge of War, following the pledges at Aqabah, Muhammad encouraged his followers to emigrate to Yathrib (Medina). Although the Quraysh tribe attempted to stop the emigration, almost all Muslims managed to leave.

Hijra

[edit | edit source]The Hijra is the migration of Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE. In September 622, warned of a plot to assassinate him, Muhammad secretly slipped out of Mecca, moving with his followers to Medina, 320 kilometrers (200 mi) north of Mecca. The Hijra is celebrated annually on the first day of the Muslim year.

Migration to Medina

A delegation consisting of the representatives of the twelve important clans of Medina, invited Muhammad as a neutral outsider to Medina to serve as chief arbitrator for the entire community. There was fighting in Medina mainly involving its Arab and Jewish inhabitants for around a hundred years before 620. The delegation from Medina pledged themselves and their fellow-citizens to accept Muhammad into their community and physically protect him as one of themselves.

Muhammad instructed his followers to emigrate to Medina until virtually all his followers left Mecca. Being alarmed at the departure of Muslims, according to the tradition, the Meccans plotted to assassinate Muhammad. With the help of Ali, Muhammad fooled the Meccans and secretly slipped away from the town. Those who migrated from Mecca along with Muhammad became known as muhajirun (emigrants).

Establishment of a new polity

Among the first things Muhammad did to settle down the longstanding grievances among the tribes of Medina was drafting a document known as the Constitution of Medina, "establishing a kind of alliance or federation" among the eight Medinan tribes and Muslim emigrants from Mecca, which specified the rights and duties of all citizens and the relationship of the different communities in Medina (including that of the Muslim community to other communities, specifically the Jews and other "Peoples of the Book"). The community defined in the Constitution of Medina, Ummah, had a religious outlook but was also shaped by practical considerations and substantially preserved the legal forms of the old Arab tribes. It effectively established the first Islamic state.

Several ordinances were proclaimed to win over the numerous and wealthy Jewish population. But these were soon rescinded as the Jews insisted on preserving the entire Mosaic law, and did not recognize him as a prophet because he was not of the race of David.

The first group of pagan converts to Islam in Medina were the clans who had not produced great leaders for themselves but had suffered from warlike leaders from other clans. This was followed by the general acceptance of Islam by the pagan population of Medina, apart from some exceptions. According to Ibn Ishaq, this was influenced by the conversion of Sa'd ibn Mu'adh (a prominent Medinan leader) to Islam. Those Medinans who converted to Islam and helped the Muslim emigrants find shelter became known as the ansar (supporters). Then Muhammad instituted brotherhood between the emigrants and the supporters and he chose Ali as his own brother.

Beginning of armed conflict

Following the emigration, the Meccans seized the properties of the Muslim emigrants in Mecca. Economically uprooted and with no available profession, the Muslim migrants turned to raiding Meccan caravans, initiating armed conflict with Mecca. Muhammad delivered Quranic verses permitting the Muslims to fight the Meccans (Quran 22:39–40). These attacks allowed the migrants to acquire wealth, power and prestige while working towards their ultimate goal of conquering Mecca.

On 11 February 624 according to the traditional account, while praying in the Masjid al-Qiblatain in Medina, Muhammad received a revelation from God that he should be facing Mecca rather than Jerusalem during prayer. As he adjusted himself, so did his companions praying with him, beginning the tradition of facing Mecca during prayer. According to Watt, the change may have been less sudden and definite than the story suggests – the related Quranic verses (2:136–2:147) appear to have been revealed at different times – and correlates with changes in Muhammad's political support base, symbolizing his turning away from Jews and adopting a more Arabian outlook.

In March 624, Muhammad led some three hundred warriors in a raid on a Meccan merchant caravan. The Muslims set an ambush for them at Badr. Aware of the plan, the Meccan caravan eluded the Muslims. Meanwhile, a force from Mecca was sent to protect the caravan, continuing forward to confront the Muslims upon hearing that the caravan was safe. The Battle of Badr began in March 624. Though outnumbered more than three to one, the Muslims won the battle, killing at least forty-five Meccans with only fourteen Muslims dead. Seventy prisoners were acquired, many of whom were soon ransomed in return for wealth or freed. Muhammad and his followers saw in the victory a confirmation of their faith as Muhammad ascribed the victory to the assistance of an invisible host of angels. The Quranic verses of this period, unlike the Meccan ones, dealt with practical problems of government and issues like the distribution of spoils.

The victory strengthened Muhammad's position in Medina and dispelled earlier doubts among his followers. As a result the opposition to him became less vocal. Pagans who had not yet converted were very bitter about the advance of Islam. Two pagans, Asma bint Marwan and Abu 'Afak, had composed verses taunting and insulting the Muslims. They were killed by people belonging to their own or related clans, and no blood-feud followed.

Muhammad expelled from Medina the Banu Qaynuqa, one of three main Jewish tribes. Although Muhammad wanted them executed, the chief of the Khazraj tribe, did not agree and they were expelled to Syria but without their property. Following the Battle of Badr, Muhammad also made mutual-aid alliances with a number of Bedouin tribes to protect his community from attacks from the northern part of Hijaz.

Conflict with Mecca

The Meccans were now anxious to avenge their defeat. To maintain their economic prosperity, the Meccans needed to restore their prestige, which had been lost at Badr. In the ensuing months, the Meccans sent ambush parties on Medina while Muhammad led expeditions on tribes allied with Mecca and sent out a raid on a Meccan caravan. Abu Sufyan subsequently gathered an army of three thousand men and set out for an attack on Medina.

A scout alerted Muhammad of the Meccan army's presence and numbers a day later. The next morning, at the Muslim conference of war, there was dispute over how best to repel the Meccans. Muhammad and many senior figures suggested that it would be safer to fight within Medina and take advantage of its heavily fortified strongholds. Younger Muslims argued that the Meccans were destroying their crops, and that huddling in the strongholds would destroy Muslim prestige. Muhammad eventually conceded to the wishes of the latter, and readied the Muslim force for battle. Thus, Muhammad led his force outside to the mountain of Uhud (where the Meccans had camped) and fought the Battle of Uhud on 23 March.

Although the Muslim army had the best of the early encounters, indiscipline on the part of strategically placed archers led to a Muslim defeat, with 75 Muslims killed including Hamza, Muhammad's uncle and one of the best known martyrs in the Muslim tradition. The Meccans did not pursue the Muslims further, but marched back to Mecca declaring victory. This is probably because Muhammad was wounded and thought to be dead. When they knew this on their way back, they did not return back because of false information about new forces coming to his aid. They were not entirely successful, however, as they had failed to achieve their aim of completely destroying the Muslims. The Muslims buried the dead, and returned to Medina that evening. Questions accumulated as to the reasons for the loss, and Muhammad subsequently delivered Quranic verses 3:152 which indicated that their defeat was partly a punishment for disobedience and partly a test for steadfastness.

Abu Sufyan now directed his efforts towards another attack on Medina. He attracted the support of nomadic tribes to the north and east of Medina, using propaganda about Muhammad's weakness, promises of booty, and use of bribes. Muhammad's policy was now to prevent alliances against him as much as he could. Whenever alliances of tribesmen against Medina were formed, he sent out an expedition to break them up. When Muhammad heard of men massing with hostile intentions against Medina, he reacted with severity. One example is the assassination of Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf, a chieftain of the Jewish tribe of Banu Nadir who had gone to Mecca and written poems that helped rouse the Meccans' grief, anger and desire for revenge after the Battle of Badr. Around a year later, Muhammad expelled the Banu Nadir from Medina to Syria allowing them to take some of their possessions because he was unable to subdue them in their strongholds. The rest of their property was claimed by Muhammad in the name of God because it was not gained with bloodshed. Muhammad surprised various Arab tribes, one by one, with overwhelming force which caused his enemies to unite to annihilate him. Muhammad's attempts to prevent formation of a confederation against him were unsuccessful, though he was able to increase his own forces and stop many potential tribes from joining his enemies.

Siege of Medina

With the help of the exiled Banu Nadir, Abu Sufyan had mustered a force of 10,000 men. Muhammad prepared a force of about 3,000 men and adopted a new form of defense unknown in Arabia at that time: the Muslims dug a trench wherever Medina lay open to cavalry attack. The idea is credited to a Persian convert to Islam, Salman the Persian. The siege of Medina began on March 31 627 and lasted for two weeks. Abu Sufyan's troops were unprepared for the fortifications they were confronted with, and after the ineffectual siege, the coalition decided to go home. The Meccans' failure resulted in a significant loss of prestige; their trade with Syria was gone. Following what came to be known as the Battle of the Trench, he made two expeditions to the north which ended without any fighting.

Truce of Hudaybiyyah

Although Muhammad had already delivered Quranic verses commanding the Hajj, the Muslims had not performed it due to the enmity of the Quraysh. In the month of Shawwal 628, Muhammad ordered his followers to obtain sacrificial animals and to make preparations for a pilgrimage (umrah) to Mecca, saying that God had promised him the fulfillment of this goal in a vision where he was shaving his head after the completion of the Hajj. Upon hearing of the approaching 1,400 Muslims, the Quraysh sent out a force of 200 cavalry to halt them. Muhammad evaded them by taking a more difficult route, thereby reaching al-Hudaybiyya, just outside of Mecca. According to Watt, although Muhammad's decision to make the pilgrimage was based on his dream, he was at the same time demonstrating to the pagan Meccans that Islam does not threaten the prestige of their sanctuary, and that Islam was an Arabian religion.

Negotiations commenced with emissaries going to and from Mecca. While these continued, rumors spread that one of the Muslim negotiators, Uthman bin al-Affan, had been killed by the Quraysh. Muhammad responded by calling upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the "Pledge of Acceptance" (بيعة الرضوان ) or the "Pledge under the Tree". News of Uthman's safety, however, allowed for negotiations to continue, and a treaty scheduled to last ten years was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraysh. The main points of the treaty included the cessation of hostilities; the deferral of Muhammad's pilgrimage to the following year; and an agreement to send back any Meccan who had gone to Medina without the permission of their protector.

Many Muslims were not satisfied with the terms of the treaty. However, the Quranic sura "Al-Fath" (The Victory) (Quran 48:1–29) assured the Muslims that the expedition from which they were now returning must be considered a victorious one. It was only later that Muhammad's followers would realise the benefit behind this treaty. These benefits included the inducing of the Meccans to recognise Muhammad as an equal; a cessation of military activity posing well for the future; and gaining the admiration of Meccans who were impressed by the incorporation of the pilgrimage rituals.

After signing the truce, Muhammad made an expedition against the Jewish oasis of Khaybar, known as the Battle of Khaybar. This was possibly due to it housing the Banu Nadir, who were inciting hostilities against Muhammad, or to regain some prestige to deflect from what appeared to some Muslims as the inconclusive result of the truce of Hudaybiyya. According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad also sent letters to many rulers of the world, asking them to convert to Islam (the exact date is given variously in the sources). Hence he sent messengers to Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire (the eastern Roman Empire), Khosrau of Persia, the chief of Yemen and to some others. In the years following the truce of Hudaybiyya, Muhammad sent his forces against the Arabs on Transjordanian Byzantine soil in the Battle of Mu'tah, in which the Muslims were defeated.

Final years

[edit | edit source]Conquest of Mecca

The truce of Hudaybiyyah had been enforced for two years. The tribe of Banu Khuza'a had good relations with Muhammad, whereas their enemies, the Banu Bakr, had an alliance with the Meccans. A clan of the Bakr made a night raid against the Khuza'a, killing a few of them. The Meccans helped the Banu Bakr with weapons and, according to some sources, a few Meccans also took part in the fighting. After this event, Muhammad sent a message to Mecca with three conditions, asking them to accept one of them. These were that either the Meccans paid blood money for those slain among the Khuza'ah tribe; or, that they should disavow themselves of the Banu Bakr; or, that they should declare the truce of Hudaybiyyah null. The Meccans replied that they would accept only the last condition. However, soon they realized their mistake and sent Abu Sufyan to renew the Hudaybiyyah treaty, but now his request was declined by Muhammad.

Muhammad began to prepare for a campaign. In 630, Muhammad marched on Mecca with an enormous force, said to number more than ten thousand men. With minimal casualties, Muhammad took control of Mecca. He declared an amnesty for past offences, except for ten men and women who were "guilty of murder or other offences or had sparked off the war and disrupted the peace". Some of these were later pardoned. Most Meccans converted to Islam and Muhammad subsequently had destroyed all the statues of Arabian gods in and around the Kaaba. According to reports collected by Ibn Ishaq and al-Azraqi, Muhammad personally spared paintings or frescos of Mary and Jesus, but other traditions suggest that all pictures were erased. The Quran discusses the conquest of Mecca.

Conquest of Arabia

Soon after the conquest of Mecca, Muhammad was alarmed by a military threat from the confederate tribes of Hawazin who were collecting an army twice the size of Muhammad's. The Banu Hawazin were old enemies of the Meccans. They were joined by the Banu Thaqif (inhabiting the city of Ta'if) who adopted an anti-Meccan policy due to the decline of the prestige of Meccans. Muhammad defeated the Hawazin and Thaqif tribes in the Battle of Hunayn.

In the same year, Muhammad made the expedition of Tabuk against northern Arabia because of their previous defeat at the Battle of Mu'tah, as well as reports of the hostile attitude adopted against Muslims. With the greatest difficulty he collected thirty thousand men, half of whom, however, on the second day after their departure from Mecca, returned untroubled by the damning verses which Muhammad hurled at them. Although Muhammad did not make contact with hostile forces at Tabuk, he received the submission of some local chiefs of the region.

He also ordered the destruction of remaining pagan idols in Eastern Arabia. The last city to hold out against the Muslims in Eastern Arabia was Taif. Muhammad refused to accept the surrender of the city until they agreed to convert to Islam and let his men destroy their statue of their goddess Allat.

A year after the Battle of Tabuk, the Banu Thaqif sent emissaries to Medina to surrender to Muhammad and adopt Islam. Many bedouins submitted to Muhammad to be safe against his attacks and to benefit from the booties of the wars.However, the bedouins were alien to the system of Islam and wanted to maintain their independence, their established code of virtue and their ancestral traditions. Muhammad thus required of them a military and political agreement according to which they "acknowledge the suzerainty of Medina, to refrain from attack on the Muslims and their allies, and to pay the Zakat, the Muslim religious levy."

Farewell pilgrimage

In 632, Muhammad carried through his first truly Islamic pilgrimage, thereby teaching his followers the rites of the annual Great Pilgrimage (hajj). After completing the pilgrimage, Muhammad delivered a famous speech known as The Farewell Sermon, at Mount Arafat east of Mecca. In this sermon, Muhammad advised his followers not to follow certain pre-Islamic customs. He declared that an Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab nor a non-Arab has any superiority over an Arab; also a white has no superiority over black nor a black has any superiority over white except by piety and good action. He abolished all old blood feuds and disputes based on the former tribal system and asked for all old pledges to be returned as implications of the creation of the new Islamic community. Commenting on the vulnerability of women in his society, Muhammed asked his male followers to “Be good to women; for they are powerless captives (awan) in your households. You took them in God’s trust, and legitimated your sexual relations with the Word of God, so come to your senses people, and hear my words ...” He told them that they were entitled to discipline their wives but should do so with kindness. He addressed the issue of inheritance by forbidding false claims of paternity or of a client relationship to the deceased, and forbade his followers to leave their wealth to a testamentary heir. He also upheld the sacredness of four lunar months in each year. According to Sunni tafsir, the following Quranic verse was delivered during this event: “Today I have perfected your religion, and completed my favours for you and chosen Islam as a religion for you.”(Quran 5:3) According to Shia tafsir, it refers to the appointment of Ali ibn Abi Talib at the pond of Khumm as Muhammad's successor, this occurring a few days later when Muslims were returning from Mecca to Medina.

Death and tomb

A few months after the farewell pilgrimage, Muhammad fell ill and suffered for several days with a fever, head pain, and weakness. He died on Monday, 8 June 632, in Medina, at the age of 63, in the house of his wife Aisha. With his head resting on Aisha's lap, he asked her to dispose of his last worldly goods (seven coins), then murmured his final words:

- Rather, God on High and paradise

- —Muhammad

He was buried where he died, in Aisha's house. During the reign of the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I, the Al-Masjid al-Nabawi (the Mosque of the Prophet) was expanded to include the site of Muhammad's tomb. The Green Dome above the tomb was built by the Mamluk sultan Al Mansur Qalawun in the 13th century, although the green color was added in the 16th century, under the reign of Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. Among tombs adjacent to Muhammad's are those of his companions (Sahabah), the first two Muslim caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar, and an empty one that Muslims believe awaits Jesus.

When bin Saud took Medina in 1805, Muhammad's tomb was stripped of its gold and jewel ornaments. Adherents to Wahhabism, bin Sauds' followers destroyed nearly every tomb dome in Medina in order to prevent their veneration, and the one of Muhammad is said to have narrowly escaped. Similar events took place in 1925 when the Saudi militias retook—and this time managed to keep—the city. In the Wahhabi interpretation of Islam, burial is to take place in unmarked graves. Although frowned upon by the Saudis, many pilgrims continue to practice a ziyarat—a ritual visit—to the tomb. Although banned by the Saudi, the first ever photos from inside of the tomb of Muhammad and his daughter's (Fatemeh) house were published on Oct 2012 demonstrating it was constructed in a very simple way, decorated in green.

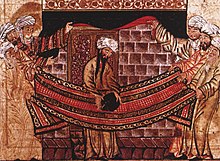

Depictions of the Prophet

[edit | edit source]

In accordance to Islamic law, all images of sentient living beings is strictly taboo. This decree is particularly strict in regards to depictions of Allah and the prophet Muhammad. For this reason, Islamic art, as seen in mosques, turns to elaborate calligraphy or geometric patterns for decorative purposes. Although there have been some exceptions, physical depictions of the prophet largely come from art made in Persia in the transitional period converting to Islam from the Buddhist faith of Persia's Mongol rulers. Muhammad's figure is often obscured by a veil or entirely symbolized by a flame.

Depictions of the prophet remain a point of contention for many devout Muslims. In 2005, the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten came under severe and often violent criticism for the publication of 12 editorial cartoons, many depicting the Prophet Muhammad.

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Muslim views

[edit | edit source]

Following the attestation to the oneness of God, the belief in Muhammad's prophethood is the main aspect of the Islamic faith. Every Muslim proclaims in the Shahadah that "I testify that there is none worthy of worship except God, and I testify that Muhammad is a Messenger of God". The Shahadah is the basic creed or tenet of Islam. Ideally, it is the first words a newborn will hear, and children are taught as soon as they are able to understand it and it will be recited when they die.

According to the Quran, Muhammad is the last of a series of Prophets sent by God for the benefit of mankind, and commands Muslims to make no distinction between them. Quran 10:37 states that "...it (the Quran) is a confirmation of (revelations) that went before it, and a fuller explanation of the Book - wherein there is no doubt - from The Lord of the Worlds." Historian Denis Gril believes that the Quran does not overtly describe Muhammad performing miracles, and the supreme miracle of Muhammad is finally identified with the Quran itself. However, Muslim tradition credits Muhammad with several miracles or supernatural events. For example, many Muslim commentators and some Western scholars have interpreted the Surah 54:1–2 as referring to Muhammad splitting the Moon in view of the Quraysh when they began persecuting his followers.

The Sunnah represents the actions and sayings of Muhammad (preserved in reports known as Hadith), and covers a broad array of activities and beliefs ranging from religious rituals, personal hygiene, burial of the dead to the mystical questions involving the love between humans and God. The Sunnah is considered a model of emulation for pious Muslims and has to a great degree influenced the Muslim culture. The greeting that Muhammad taught Muslims to offer each other, “may peace be upon you” (as-salamu `alaykum) is used by Muslims throughout the world. Many details of major Islamic rituals such as daily prayers, the fasting and the annual pilgrimage are only found in the Sunnah and not the Quran.

The Sunnah also played a major role in the development of the Islamic sciences. It contributed much to the development of Islamic law, particularly from the end of the first Islamic century. Muslim mystics, known as sufis, who were seeking for the inner meaning of the Quran and the inner nature of Muhammad, viewed the prophet of Islam not only as a prophet but also as a perfect saint. Sufi orders trace their chain of spiritual descent back to Muhammad.

Muslims have traditionally expressed love and veneration for Muhammad. Stories of Muhammad's life, his intercession and of his miracles (particularly "Splitting of the moon") have permeated popular Muslim thought and poetry. Among Arabic odes to Muhammad, the Qaṣīda al-Burda ("Poem of the Mantle") by the Egyptian Sufi al-Busiri (1211–1294) is particularly well known, and widely held to possess a healing, spiritual power. The Quran refers to Muhammad as "a mercy (rahmat) to the worlds" (Quran 21:107). The association of rain with mercy in Oriental countries has led to imagining Muhammad as a rain cloud dispensing blessings and stretching over lands, reviving the dead hearts, just as rain revives the seemingly dead earth (see, for example, the Sindhi poem of Shah ʿAbd al-Latif). Muhammad's birthday is celebrated as a major feast throughout the Islamic world, excluding Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia where these public celebrations are discouraged. When Muslims say or write the name of Muhammad or any other prophet in Islam, they usually follow it with "Peace be upon him." In casual writing, this is sometimes abbreviated as PBUH or SAW; in printed matter, a small calligraphic rendition is commonly used instead of printing the entire phrase.

Other views

[edit | edit source]Non-Muslim views regarding Muhammad have ranged across a large spectrum of responses and beliefs, many of which have changed over time.

European and Western views

According to Prof. Hossein Nasr, earliest European literature often refers to Muhammad unfavorably. A few learned circles of Middle Ages Europe—primarily Latin-literate scholars—had access to fairly extensive biographical material about Muhammad. They interpreted that information through a Christian religious filter that viewed Muhammad as a charlatan driven by ambition and eagerness for power, and who seduced the Saracens into his submission under a religious guise. Popular European literature of the time portrayed Muhammad as though he were worshiped by Muslims in the manner of an idol or a heathen god.Some medieval Christians believed he died in 666, alluding to the number of the beast, instead of his actual death date in 632; others changed his name from Muhammad to Mahound, the "devil incarnate". Historian Bernard Lewis writes "The development of the concept of Mahound started with considering Muhammad as a kind of demon or false god worshiped with Apollyon and Termagant in an unholy trinity." A later medieval work, Livre dou Tresor represents Muhammad as a former monk and cardinal. Dante's Divine Comedy (Canto XXVIII), puts Muhammad, together with Ali, in Hell "among the sowers of discord and the schismatics, being lacerated by devils again and again." Cultural critic and author Edward Said wrote in Orientalism regarding Dante's depiction of Muhammad:

- Empirical data about the Orient...count for very little; ... What ... Dante tried to do in the Inferno, is ... to characterize the Orient as alien and to incorporate it schematically on a theatrical stage whose audience, manager, and actors are ... only for Europe. Hence the vacillation between the familiar and the alien; Mohammed is always the imposter (familiar, because he pretends to be like the Jesus we know) and always the Oriental (alien, because although he is in some ways "like" Jesus, he is after all not like him).

After the Reformation, Muhammad was often portrayed as a cunning and ambitious impostor. French scholar Guillaume Postel was among the first to present a more positive view of Muhammad. French historian Henri de Boulainvilliers described Muhammad as a gifted political leader and a just lawmaker. German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz praised Muhammad because "he did not deviate from the natural religion". Thomas Carlyle in his book Heroes and Hero Worship and the Heroic in History (1840) describes Muhammed as "[a] silent great soul; [...] one of those who cannot but be in earnest". Historian Edward Gibbon in his book The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire observes that "the good sense of Mohammad despised the pomp of royalty." German author Friedrich Martin von Bodenstedt (1851) described Muhammad as "an ominous destroyer and a prophet of murder." English Professor Simon Ockley wrote in his book The History of the Saracen Empires (1718):

- The greatest success of Mohammad’s life was effected by sheer moral force...It is not the propagation but the permanency of his religion that deserves our wonder, the same pure and perfect impression which he engraved at Mecca and Medina is preserved, after the revolutions of twelve centuries by the Indian, the African and the Turkish proselytes of the Koran. . . The Mahometans have uniformly withstood the temptation of reducing the object of their faith and devotion to a level with the senses and imagination of man. 'I believe in One God and Mahomet the Apostle of God' is the simple and invariable profession of Islam. The intellectual image of the Deity has never been degraded by any visible idol; the honours of the prophet have never transgressed the measure of human virtue, and his living precepts have restrained the gratitude of his disciples within the bounds of reason and religion.

Reverend Benjamin Bosworth Smith in his book Muhammad and Muhammadanism (1874) commented that:

- ...if ever any man had the right to say that he ruled by the right divine, it was Mohammed, for he had all the power without its instruments and without its supports. He cared not for the dressings of power. The simplicity of his private life was in keeping with his public life...In Mohammadanism every thing is different here. Instead of the shadowy and the mysterious, we have history....We know of the external history of Muhammad....while for his internal history after his mission had been proclaimed, we have a book absolutely unique in its origin, in its preservation....on the Substantial authority of which no one has ever been able to cast a serious doubt.

Alphonse de Lamartine's Histoire de la Turquie (1854) says about Muhammad:

- If greatness of purpose, smallness of means and outstanding results are the three criteria of human genius, who could dare compare any great man in modern history with Muhammad...Never has a man proposed for himself, voluntarily or involuntarily, a goal more sublime, since this goal was beyond measure: undermine the superstitions placed between the creature and the Creator, give back God to man and man to God, reinstate the rational and saintly idea of divinity in the midst of this prevailing chaos of material and disfigured gods of idolatry.... The most famous have only moved weapons, laws, empires; they founded, when they founded anything, only material powers, often crumbling before them. This one not only moved armies, legislations, empires, peoples, dynasties, millions of men over a third of the inhabited globe; but he also moved ideas, beliefs, souls. He founded upon a book, of which each letter has become a law, a spiritual nationality embracing people of all languages and races; and made an indelible imprint upon this Muslim world, for the hatred of false gods and the passion for the God, One and Immaterial. ... Philosopher, orator, apostle, legislator, warrior, conqueror of ideas, restorer of a rational dogma for a cult without imagery, founder of twenty earthly empires and of a spiritual empire, this is Muhammad.

British writer Annie Besant in The Life and Teachings of Muhammad (1932) wrote:

- It is impossible for anyone who studies the life and character of the great Prophet of Arabia, who knows how he taught and how he lived, to feel anything but reverence for that mighty Prophet, one of the great messengers of the Supreme...

According to Prof. William Montgomery Watt and Richard Bell, recent writers have generally dismissed the idea that Muhammad deliberately deceived his followers, arguing that Muhammad "was absolutely sincere and acted in complete good faith" and that Muhammad’s readiness to endure hardship for his cause when there seemed to be no rational basis for hope shows his sincerity. Watt says that sincerity does not directly imply correctness: In contemporary terms, Muhammad might have mistaken his own subconscious for divine revelation. Watt and Bernard Lewis argue that viewing Muhammad as a self-seeking impostor makes it impossible to understand the development of Islam. Alford T. Welch holds that Muhammad was able to be so influential and successful because of his firm belief in his vocation. Michael H. Hart in his first book The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History (1978), a ranking of the 100 people who most influenced human history, chose Muhammad as the first person on his list, attributing this to the fact that Muhammad was "supremely successful" in both the religious and secular realms. He also credits the authorship of the Quran to Muhammad, making his role in the development of Islam an unparalleled combination of secular and religious influence which entitles Muhammad to be considered the most influential single figure in human history.

Other religious traditions

The Bahá'í faith venerate Muhammad as one of a number of prophets or "Manifestations of God", but consider his teachings to have been superseded by those of Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahai faith.

Very few texts in Judaism refer to or take note of Muhammad. Those that do reject Muhammad's self-proclamation of receiving divine revelations from God and label him instead as a false prophet.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints neither regards Muhammad as a prophet nor accepts the Quran as a book of scripture. However, it does respect Muhammad as one who taught moral truths which can enlighten nations and bring a higher level of understanding to individuals.

Attribution

[edit | edit source]"Muhammad" (Wikipedia) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad