Saylor.org's Ancient Civilizations of the World/The Fall of Rome’s Empire and the Rise of Medieval Europe

The Fall of Rome’s Empire and the Rise of Medieval Europe

[edit | edit source]

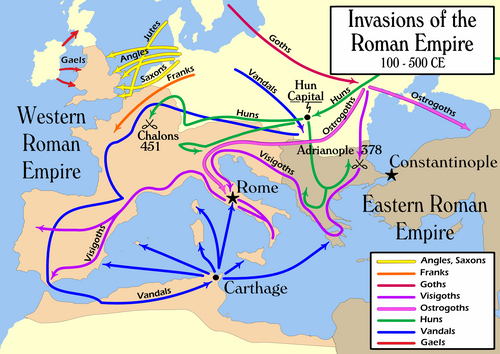

As Roman power ebbed, tribes from outside the old borders moved in to fill the vacuum. Visigoths set up a new kingdom in Iberia, while Vandals settled eventually in north Africa. In Britain, Germanic tribes arrived and settled on the east coast in 5CE. These settlers eventually formed small Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which filled the vacuum left by the departure of the Romans. Post-Roman Italy itself came under the sway of the Ostrogoths, whose most influential king, Theoderic, was hailed as a new emperor by the Roman Senate, and had good relations with the Christian pope, but kept his seat of power at Ravenna in northern Italy. Southern Italy and Sicily were under the sway of the Byzantine Emperor for several centuries during this period.

The province of Gaul, which had been the most prosperous of the Western Roman provinces, came into the possession of the Franks. The Roman-Gaulish society and its leaders eventually assimilated with the Franks, relying on their warriors for security and cementing connections of marriage with Frankish clans. The new Frankish kingdom came to include much of modern western Germany and northern France, its power within this region made clear by victories over the Visigoths and other barbarian rivals. Today the German word for France, Frankreich, pays homage to the Frankish kingdom of times past.

The Merovingian dynasty, named after the legendary tribal king Merovech, was first to rule over the Frankish realm. Their most skilled and powerful ruler, Clovis, converted to Catholic Christianity in 496 as a promise for victory in battle. At Clovis's death, he divided his kingdom up among his many sons, whose rivalries touched off a century of intermittent and bloody civil war. Some, like Chilperic, were insane, and none were willing to give up lands or power to reunify the kingdom. The fortunes of the Merovingians ebbed and they faded into irrelevance.

The rise of a new ruling power, the Carolingian dynasty, was the result of the expanded power of the Majordomo, or "head of the house". Merovingian kings gave their majordomo extensive power to command and control their estates, and some of them used this power to command and control entire territories. Pepin II was one of the first to expand his power so much that he held power over almost all of Gaul. His son, also a majordomo, Charles Martel, won the Battle of Tours against invading Islamic armies, keeping Muslim influence out of most of Europe. "Martel", meaning "The Hammer", was a reference to his weapon of choice. Martel's son, Pepin III the Short, after requesting support of the papacy, disposed of the Merovingian "puppets". The papacy gave Pepin permission to overthrow the Merovingians in order to secure Frankish support of the papal states, and protection against Lombard incursion. Pepin was declared rex Dei gratia, "King by the grace of God", thereby setting a powerful precedent for European absolutism, by arguing that it was the Christian God's will to declare someone a king. (Both Pepin II and Pepin III were known as Pepin the Younger, as Pepin I was Pepin the Elder. However, Pepin III is also known as Pepin the Short, so that is the name that will be used here.)

Pepin the Short was the founder of the Carolingian dynasty, which culminated in his son Charlemagne, "Charles the Great". Charlemagne was also the first king crowned Holy Roman Emperor -- the supposed successor to the Caesars and the protector of the Catholic Church.

Attribution

[edit | edit source]"European History: A Background of European History-Barbarians Unite" (Wikibooks) http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/European_History/A_Background_of_European_History#Barbarians_Unite