Saylor.org's Ancient Civilizations of the World/Confucius and Confucianism

Introduction

[edit | edit source]

Confucianism (儒敎) is a complex belief system, which was found by Confucius (551-479 BCE). The system is based on his teachings that primarily focus on individual morality, ethics and the proper exercise of political power by rulers. It was spread out to China, Japan, Korea and some other areas in Asia and influenced on philosophies and thoughts in those areas for thousands years. There are approximately 6 million Confucians in the world; about 26,000 in North America and almost all of the remainder throughout China and rest of Asia. However, because the belief system has became part of culture in those areas, especially in Asia, it is often debated whether Confucianism is still a religion or a philosophy. Confucianism is rooted in a belief in humanism and non-theism, meaning that it is not predicated upon a belief in a personal of creator God. That being said, some Confucians take to revering Confucius as a divine prophet. In South Korea, ancestor worship, which is a practice of Confucianism, is still performed in many households and values of ethical teachings are considered very importantly.

Confucius

[edit | edit source]Confucius (551–479 BCE) was a Chinese teacher, editor, politician, and philosopher of the Spring and Autumn Period of Chinese history. The philosophy of Confucius emphasized personal and governmental morality, correctness of social relationships, justice and sincerity. His followers competed successfully with many other schools during the Hundred Schools of Thought era only to be suppressed in favor of the Legalists during the Qin Dynasty. Following the victory of Han over Chu after the collapse of Qin, Confucius's thoughts received official sanction and were further developed into a system known as Confucianism.

Confucius is traditionally credited with having authored or edited many of the Chinese classic texts including all of the Five Classics, but modern scholars are cautious of attributing specific assertions to Confucius himself. Aphorisms concerning his teachings were compiled in the Analects, but only many years after his death.

Confucius's principles had a basis in common Chinese tradition and belief. He championed strong family loyalty, ancestor worship, respect of elders by their children (and in traditional interpretations) of husbands by their wives. He also recommended family as a basis for ideal government. He espoused the well-known principle "Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself", an early version of the Golden Rule.

Personal Life

[edit | edit source]

According to Kung-yang and Kuh-liang, Confucius was born in 551 B.C, in Zou, Lu state (near present-day Qufu, Shandong Province). The name "Confucius" is merely the latinized form of Kung Fu-tze, meaning "the philosopher or master K`ung;" K'ung being the name of his clan. His father Kong He was an officer in the Lu military. Kong He died when Confucius was three years old. As a child, Confucius was raised by his mother in poverty. He married a woman named Qi Guan at age 19. A year later, the couple had their first child, Kong Li, both of whom Confucius was to abandon to develop his ideologies. Confucius spent the following decades build up a considerable reputation through his teachings. Many powerful families sought his help in the hope of achieving loyalty to a legitimate government. Thus, in 501 BCE, Confucius came to be appointed to the minor position of governor of a town. Eventually, he rose to the position of Minister of Crime. After failing to gain the adherence of the most powerful clans, Confucius departed the state of Lu, in 497 BCE, remaining in self-exile until 483 BCE. During his exile, Confucius began a long journey or set of journeys around the small kingdoms of northeast and central China, traditionally including the states of Wei, Song, Chen, and Cai. At the courts of these states, he expounded his political beliefs but did not see them implemented. According to the Zuo Zhuan, Confucius returned home when he was 68. The Analects depict him spending his last years teaching 72 or 77 disciples and transmitting the old wisdom via a set of texts called the Five Classics.

Philosophy

[edit | edit source]Although Confucianism is often followed in a religious manner by the Chinese, arguments continue over whether it is a religion. Confucianism discusses elements of the afterlife and views concerning Heaven, but it is relatively unconcerned with some spiritual matters often considered essential to religious thought, such as the nature of souls. In the Analects, Confucius presents himself as a "transmitter who invented nothing". He puts the greatest emphasis on the importance of study, and it is the Chinese character for study (學) that opens the text. Far from trying to build a systematic or formalist theory, he wanted his disciples to master and internalize the old classics, so that their deep thought and thorough study would allow them to relate the moral problems of the present to past political events (as recorded in the Annals) or the past expressions of commoners' feelings and noblemen's reflections (as in the poems of the Book of Odes).

Ethics

[edit | edit source]One of the deepest teachings of Confucius may have been the superiority of personal exemplification over explicit rules of behavior. His moral teachings emphasized self-cultivation, emulation of moral exemplars, and the attainment of skilled judgment rather than knowledge of rules. Confucian ethics may be considered a type of virtue ethics. His teachings rarely rely on reasoned argument and ethical ideals and methods are conveyed more indirectly, through allusion, innuendo, and even tautology. His teachings require examination and context in order to be understood. A good example is found in this famous anecdote:

- When the stables were burnt down, on returning from court Confucius said, "Was anyone hurt?" He did not ask about the horses.

By not asking about the horses, Confucius demonstrates that the sage values human beings over property; readers are led to reflect on whether their response would follow Confucius's and to pursue self-improvement if it would not have. Confucius, as an exemplar of human excellence, serves as the ultimate model, rather than a deity or a universally true set of abstract principles. For these reasons, according to many commentators, Confucius's teachings may be considered a Chinese example of humanism.

One of his most famous teachings was a variant of the "Golden Rule":

- What you do not wish for yourself, do not do to others.

Although the above rules are in some way universal, Confucius was called an ethical particularist because of how he interpreted these rules. Confucius believed that there is a duty to family and friends before there is a duty to community. Therefore, in different situations Confucius counseled a person to do different things.

Often overlooked in Confucian ethics are the virtues to the self: sincerity and the cultivation of knowledge. Virtuous action towards others begins with virtuous and sincere thought, which begins with knowledge. A virtuous disposition without knowledge is susceptible to corruption and virtuous action without sincerity is not true righteousness. Cultivating knowledge and sincerity is also important for one's own sake; the superior person loves learning for the sake of learning and righteousness for the sake of righteousness.

The Confucian theory of ethics as exemplified in Lǐ (禮) is based on three important conceptual aspects of life: ceremonies associated with sacrifice to ancestors and deities of various types, social and political institutions, and the etiquette of daily behavior. It was believed by some that lǐ originated from the heavens, but Confucius stressed the development of lǐ through the actions of sage leaders in human history. His discussions of lǐ seem to redefine the term to refer to all actions committed by a person to build the ideal society, rather than those simply conforming with canonical standards of ceremony.

In the early Confucian tradition, lǐ was doing the proper thing at the proper time, balancing between maintaining existing norms to perpetuate an ethical social fabric, and violating them in order to accomplish ethical good. Training in the lǐ of past sages cultivates in people virtues that include ethical judgment about when lǐ must be adapted in light of different contexts or situations.

In Confucianism, the concept of li is closely related to yì (義), which is based upon the idea of reciprocity. Yì can be translated as righteousness, though it may simply mean what is ethically best to do in a certain context. The term contrasts with action done out of self-interest. While pursuing one's own self-interest is not necessarily bad, one would be a better, more righteous person if one's life was based upon following a path designed to enhance the greater good. Thus an outcome of yì is doing the right thing for the right reason.

Just as action according to Lǐ should be adapted to conform to the aspiration of adhering to yì, so yì is linked to the core value of rén (仁).Rén consists of 5 basic virtues: seriousness, generosity, sincerity, diligence and kindness. Rén is the virtue of perfectly fulfilling one's responsibilities toward others, most often translated as "benevolence" or "humaneness"; translator Arthur Waley calls it "Goodness" (with a capital G), and other translations that have been put forth include "authoritativeness" and "selflessness." Confucius's moral system was based upon empathy and understanding others, rather than divinely ordained rules. To develop one's spontaneous responses of rén so that these could guide action intuitively was even better than living by the rules of yì. Confucius asserts that virtue is a means between extremes. For example, the properly generous person gives the right amount—not too much and not too little.

Politics

[edit | edit source]Confucius' political thought is based upon his ethical thought. He argues that the best government is one that rules through "rites" (lǐ) and people's natural morality, rather than by using bribery and coercion. He explained that this is one of the most important analects: "If the people be led by laws, and uniformity sought to be given them by punishments, they will try to avoid the punishment, but have no sense of shame. If they be led by virtue, and uniformity sought to be given them by the rules of propriety, they will have the sense of the shame, and moreover will become good." (Translated by James Legge) in the Great Learning (大學). This "sense of shame" is an internalisation of duty, where the punishment precedes the evil action, instead of following it in the form of laws as in Legalism.

Confucius looked nostalgically upon earlier days, and urged the Chinese, particularly those with political power, to model themselves on earlier examples. In times of division, chaos, and endless wars between feudal states, he wanted to restore the Mandate of Heaven (天命) that could unify the "world" (天下, "all under Heaven") and bestow peace and prosperity on the people. Because his vision of personal and social perfections was framed as a revival of the ordered society of earlier times, Confucius is often considered a great proponent of conservatism, but a closer look at what he proposes often shows that he used (and perhaps twisted) past institutions and rites to push a new political agenda of his own: a revival of a unified royal state, whose rulers would succeed to power on the basis of their moral merits instead of lineage. These would be rulers devoted to their people, striving for personal and social perfection, and such a ruler would spread his own virtues to the people instead of imposing proper behavior with laws and rules.

While he supported the idea of government by an all-powerful sage, ruling as an Emperor, his ideas contained a number of elements to limit the power of rulers. He argued for according language with truth, and honesty was of paramount importance. Even in facial expression, truth must always be represented. Confucius believed that if a ruler were to lead correctly, by action, that orders would be deemed unnecessary in that others will follow the proper actions of their ruler. In discussing the relationship between a king and his subject (or a father and his son), he underlined the need to give due respect to superiors. This demanded that the inferior must give advice to his superior if the superior was considered to be taking the course of action that was wrong. Confucius believed in ruling by example, if you lead correctly, orders are unnecessary and useless.

Writings

[edit | edit source]

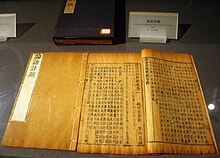

Actually, it is believed that Confucius did not write down any of his teachings. The Analects, or Selected Sayings, also known as the Analects of Confucius, is the collection of sayings and ideas attributed to the Chinese philosopher Confucius and his contemporaries, traditionally believed to have been written by Confucius' followers during the Warring States period (475 BCE - 221 BCE), and it achieved its final form during the mid-Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE). By the early Han dynasty the Analects was considered merely a "commentary" on the Five Classics, but the status of the Analects grew to be one of the central texts of Confucianism by the end of that dynasty. During the late Song dynasty (960-1279) the importance of the Analects as a philosophy work was raised above that of the older Five Classics, and it was recognized as one of the "Four Books". The Analects has been one of the most widely read and studied books in China for the last 2,000 years, and continues to have a substantial influence on Chinese and East Asian thought and values today.

Contents

[edit | edit source]Very few reliable sources about Confucius exist. The principal biography available to historians is included in Sima Qian's Shiji; but, because the Shiji contains a large amount of (possibly legendary) material not confirmed by other sources, the biographical material on Confucius found in the Analects makes the Analects arguably the most reliable source of biographical information about Confucius. Confucius viewed himself as a "transmitter" of social and political traditions originating in the early Zhou dynasty (c.1000-800 BCE), and claimed not to have originated anything (Analects 7.1), but Confucius' social and political ideals were not popular in his time.

Social philosophy

[edit | edit source]Confucius' discussions on the nature of the supernatural (Analects 3.12; 6.20; 11.11) indicate that he respected Heaven but believed that "spirits" were too difficult to understand, and that human beings should intead base their values and social ideals on moral philosophy, tradition, and a natural love for others. Confucius' social philosophy largely depended on the cultivation of ren by every individual in a community. Later Confucian philosophers discussed ren as the quality of having a kind manner, similar to the English words "humane", "altruistic", or "benevolent"; but, of the sixty instances in which Confucius discusses ren in the Analects, very few have this later meaning. Confucius instead used the term ren to describe an extremely general and all-encompassing state of virtue, one which no living person had attained completely. (This use of the term ren is peculiar to the Analects).

Throughout the Analects, Confucius' students frequently request that Confucius define ren and give examples of people who embody it, but Confucius generally responds indirectly to his students' questions, instead offering illustrations and examples of behaviours that are associated with ren and explaining how a person could achieve it. According to Confucius, a person with a well-cultivated sense of ren would: speak carefully and modestly (Analects 12.3); be resolute and firm (Analects 12.20); be courageous (Analects 14.4); be free from worry, unhappiness, and insecurity (Analects 9.28; 6.21); moderate their desires and return to propriety (Analects 12.1); be respectful, tolerant, diligent, trustworthy, and kind (Analects 17.6); and, would love others (Analects 12.22). Confucius recognized his followers' disappointment that he would not give them a more comprehensive definition of ren, but assured them that he was sharing all that he could (Analects 7.23).

To Confucius, the cultivation of ren involved depreciating oneself through modesty while avoiding artful speech and ingratiating manners that would create a false impression of one's own quality (Analects 1.3). Confucius said that those who had cultivated ren could be distinguished by their being "simple in manner and slow of speech". He believed that people could cultivate their sense of ren through exercising the Golden Rule: "Do not do to others what you would not like done to yourself"; "a man with ren, desiring to establish himself, helps others establish themselves; desiring to succeed himself, helps others to succeed" (Analects 12.2; 6.28). Confucius regarded the exercise of devotion to one's parents and older siblings as the simplest, most basic way to cultivate ren (Analects 1.2).

Confucius believed that ren could best be cultivated by those who had already learned self-discipline, and that self-discipline was best learned by practicing and cultivating one's understanding of li: rituals and forms of propriety through which people demonstrate their respect for others and their responsible roles in society (Analects 3.3). Confucius said that one's understanding of li should inform everything that one says and does (Analects 12.1). He believed that subjecting oneself to li did not mean suppressing one's desires, but learning to reconcile them with the needs of one's family and broader community. By leading individuals to express their desires within the context of social responsibility, Confucius and his followers taught that the public cultivation of li was the basis of a well-ordered society (Analects 2.3).

Ren and li have a special relationship in the Analects: li manages one's relationship with one's family and close community, while ren is practiced broadly and informs one's interactions with all people. Confucius did not believe that ethical self-cultivation meant unquestioned loyalty to an evil ruler. He argued that the demands of ren and li meant that rulers could oppress their subjects only at their own peril: "You may rob the Three Armies of their commander, but you cannot deprive the humblest peasant of his opinion" (Analects 9.25). Confucius said that a morally well-cultivated individual would regard his devotion to loving others as a mission for which he would be willing to die (Analects 15.8).

Political philosophy

[edit | edit source]

Confucius' political beliefs were rooted in his belief that a good ruler would be self-disciplined, would govern his subjects through education and by his own example, and would seek to correct his subjects with love and concern rather than punishment and coercion. "If the people be led by laws, and uniformity among them be sought by punishments, they will try to escape punishment and have no sense of shame. If they are led by virtue, and uniformity sought among them through the practice of ritual propriety, they will possess a sense of shame and come to you of their own accord" (Analects 2.3; see also 13.6). Confucius' political theories were directly contradictory to the Legalistic political orientations of China's rulers, and he failed to popularize his ideals among China's leaders within his own lifetime.

Confucius believed that the social chaos of his time was largely due to China's ruling elite aspiring to, and claiming, titles to which they were unworthy. When the ruler of the large state of Qi asked Confucius about the principles of good government, Confucius responded: "Good government consists in the ruler being a ruler, the minister being a minister, the father being a father, and the son being a son" (Analects 12.11). Confucius' analysis of the need to raise officials' behaviour to reflect the way that they identify and describe themselves is known as the rectification of names, and he stated that the rectification of names should be the first responsibility of a ruler upon taking office (Analects 13.3). Confucius believed that, because the ruler was the model for all under him in society, the rectification of names had to begin with the ruler, and that afterwards others would change to imitate him (Analects 12.19).

Confucius judged a good ruler by his possession of de ("virtue"): a sort of moral force that allows those in power to rule and gain the loyalty of others without the need for physical coercion (Analects 2.1). Confucius said that one of the most essential ways that a ruler cultivates his sense of de is through a devotion to the correct practices of li. Examples of rituals identified by Confucius as important to cultivate a ruler's de include: sacrificial rites held at ancestral temples to express thankfulness and humility; ceremonies of enfeoffment, toasting, and gift exchanges that bound nobility in complex hierarchical relationships of obligation and indebtedness; and, acts of formal politeness and decorum (i.e. bowing and yielding) that identify the performers as morally well-cultivated.

Education

[edit | edit source]The importance of education and study is a fundamental theme of the Analects. For Confucius, a good student respects and learns from the words and deeds of his teacher, and a good teacher is someone older who is familiar with the ways of the past and the practices of antiquity (Analects 7.22). Confucius emphasized the need to find balance between formal study and intuitive self-reflection (Analects 2.15). When teaching he is never cited in the Analects as lecturing at length about any subject, but instead challenges his students to discover the truth through asking direct questions, citing passages from the classics, and using analogies (Analects 7.8). His primary goal in educating his students was to produce ethically well-cultivated men who would carry themselves with gravity, speak correctly, and demonstrate consummate integrity in all things (Analects 12.11; see also 13.3). He was willing to teach anyone regardless of social class, as long as they were sincere, eager, and tireless to learn (Analects 7.7; 15.38). He is traditionally credited with teaching three thousand students, though only seventy are said to have mastered what he taught. He taught practical skills, but regarded moral self-cultivation as his most important subject.

Confucianism

[edit | edit source]

As mentioned before, Confucianism is a Chinese ethical and philosophical system developed from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius. The core of Confucianism is humanism, the belief that human beings are teachable, improvable and perfectible through personal and communal endeavour especially including self-cultivation and self-creation. Confucianism focuses on the cultivation of virtue and maintenance of ethics, the most basic of which are ren, yi, and li. Ren is an obligation of altruism and humaneness for other individuals within a community, yi is the upholding of righteousness and the moral disposition to do good, and li is a system of norms and propriety that determines how a person should properly act within a community. Confucianism holds that one should give up one's life, if necessary, either passively or actively, for the sake of upholding the cardinal moral values of ren and yi. Although Confucius the man may have been a believer in Chinese folk religion, Confucianism as an ideology is humanistic and non-theistic, and does not involve a belief in the supernatural or in a personal god.

Cultures and countries strongly influenced by Confucianism include mainland China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, as well as various territories settled predominantly by Chinese people, such as Singapore. Although Confucian ideas prevail in these areas, few people outside of academia identify themselves as Confucian, and instead see Confucian ethics as a complementary guideline for other ideologies and beliefs, including democracy, Marxism, capitalism, Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism.

Names and Etymology

[edit | edit source]Strictly speaking, there is no term in Chinese which directly corresponds to "Confucianism." Several different terms are used in different situations, several of which are of modern origin:

- "School of the scholars" (儒家)

- "Teaching of the scholars" (儒教)

- "Study of the scholars" (儒学)

- "Teaching of Confucius" (孔教)

- "Kong Family's Business" (孔家店)

Three of these use the Chinese character 儒 rú, meaning "scholar". These names do not use the name "Confucius" at all, but instead center on the figure or ideal of the Confucian scholar; however, the suffixes of jiā, jiào, and xué carry different implications as to the nature of Confucianism itself.

Rújiā contains the character jiā, which literally means "house" or "family". In this context, it is more readily construed as meaning "school of thought", since it is also used to construct the names of philosophical schools contemporary with Confucianism: for example, the Chinese names for Legalism and Mohism end in jiā.

Rújiào and Kǒngjiào contain the Chinese character jiào, the noun "teach", used in such as terms as "education", or "educator". The term, however, is notably used to construct the names of religions in Chinese: the terms for Islam, Judaism, Christianity, and other religions in Chinese all end with jiào.

Rúxué contains xué 'study'. The term is parallel to -ology in English, being used to construct the names of academic fields: the Chinese names of fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, political science, economics, and sociology all end in xué.

Themes in Confucian thought

[edit | edit source]Humanism is at the core in Confucianism. A simple way to appreciate Confucian thought is to consider it as being based on varying levels of honesty, and a simple way to understand Confucian thought is to examine the world by using the logic of humanity. In practice, the primary foundation and function of Confucianism is as an ethical philosophy to be practiced by all the members of a society. Confucian ethics is characterized by the promotion of virtues, encompassed by the Five Constants, or the Wuchang (五常), extrapolated by Confucian scholars during the Han Dynasty. The five virtues are:

- Rén (仁, Humaneness)

- Yì (義, Righteousness or Justice)

- Lǐ (禮, Propriety or Etiquette)

- Zhì (智, Knowledge)

- Xìn (信, Integrity)

These are accompanied by the classical Sìzì (四字) with four virtues:

- Zhōng (忠, Loyalty)

- Xiào (孝, Filial piety)

- Jié (節, Continency)

- Yì (義, Righteousness)

There are still many other elements, such as Chéng (誠, honesty) and Shù (恕, kindness and forgiveness), but among all elements, Rén and Yi are fundamental.

Rén

[edit | edit source]Rén is one of the basic virtues promoted by Confucius, and is an obligation of altruism and humaneness for other individuals within a community. Confucius' concept of humaneness or rén is probably best expressed in the Confucian version of the ethic of reciprocity, or the Golden Rule: "Do not do unto others what you would not have them do unto you."

Confucius never stated whether man was born good or evil, noting that 'By nature men are similar; by practice men are wide apart'—implying that whether good or bad, Confucius must have perceived all men to be born with intrinsic similarities, but that man is conditioned and influenced by study and practise. Xunzi's opinion is that men originally just want what they instinctively want despite positive or negative results it may bring, so cultivation is needed. In Mencius' view, all men are born to share goodness such as compassion and good heart, although they may become wicked. The Three Character Classic begins with "People at birth are naturally good (kind-hearted)", which stems from Mencius' idea. All the views eventually lead to recognize the importance of human education and cultivation.

Rén also has a political dimension. If the ruler lacks rén, Confucianism holds, it will be difficult if not impossible for his subjects to behave humanely. Rén is the basis of Confucian political theory: it presupposes an autocratic ruler, exhorted to refrain from acting inhumanely towards his subjects. An inhumane ruler runs the risk of losing the "Mandate of Heaven", the right to rule. A ruler lacking such a mandate need not be obeyed. But a ruler who reigns humanely and takes care of the people is to be obeyed strictly, for the benevolence of his dominion shows that he has been mandated by heaven. Confucius himself had little to say on the will of the people, but his leading follower Mencius did state on one occasion that the people's opinion on certain weighty matters should be considered.

Li

[edit | edit source]In Confucianism, the term "li," sometimes translated into English as rituals, customs, rites, etiquette, or morals, refers to any of the secular social functions of daily life, akin to the Western term for culture. Confucius considered education and music as various elements of li. Li were codified and treated as a comprehensive system of norms, guiding the propriety or politeness which colors everyday life. Confucius himself tried to revive the etiquette of earlier dynasties.

It is important to note that, although li is sometimes translated as "ritual" or "rites", it has developed a specialized meaning in Confucianism, as opposed to its usual religious meanings. In Confucianism, the acts of everyday life are considered rituals. Rituals are not necessarily regimented or arbitrary practices, but the routines that people often engage in, knowingly or unknowingly, during the normal course of their lives. Shaping the rituals in a way that leads to a content and healthy society, and to content and healthy people, is one purpose of Confucian philosophy.

Zhōng

[edit | edit source]Zhōng or Loyalty (忠) is the equivalent of filial piety on a different plane. It is particularly relevant for the social class to which most of Confucius' students belonged, because the only way for an ambitious young scholar to make his way in the Confucian Chinese world was to enter a ruler's civil service. Like filial piety, however, loyalty was often subverted by the autocratic regimes of China. Confucius had advocated a sensitivity to the realpolitik of the class relations in his time; he did not propose that "might makes right", but that a superior who had received the "Mandate of Heaven" (see below) should be obeyed because of his moral rectitude.

In later ages, however, emphasis was placed more on the obligations of the ruled to the ruler, and less on the ruler's obligations to the ruled. Loyalty was also an extension of one's duties to friends, family, and spouse. Loyalty to one's family came first, then to one's spouse, then to one's ruler, and lastly to one's friends. Loyalty was considered one of the greater human virtues. Confucius also realized that loyalty and filial piety can potentially conflict.

Xiào

[edit | edit source]Xiào or filial piety (孝) is considered among the greatest of virtues and must be shown towards both the living and the dead (including even remote ancestors). The term "filial" (meaning "of a child") characterizes the respect that a child, originally a son, should show to his parents. This relationship was extended by analogy to a series of five relationships also known as the "five bonds":

- Ruler to Ruled

- Father to Son

- Husband to Wife

- Elder Brother to Younger Brother

- Friend to Friend

Specific duties were prescribed to each of the participants in these sets of relationships. Such duties were also extended to the dead, where the living stood as sons to their deceased family. This led to the veneration of ancestors. The only relationship where respect for elders wasn't stressed was the Friend to Friend relationship. In all other relationships, high reverence was held for elders.

The main source of our knowledge of the importance of filial piety is the Classic of Filial Piety, a work attributed to Confucius and his son but almost certainly written in the 3rd century BCE. The Analects, the main source of the Confucianism of Confucius, actually has little to say on the matter of filial piety and some sources believe the concept was focused on by later thinkers as a response to Mohism. Nevertheless, the concept of filial piety has continued to play a central role in Confucian thinking to the present day. This idea influenced the Chinese legal system: a criminal would be punished more harshly if the culprit had committed the crime against a parent, while fathers often exercised enormous power over their children. A similar differentiation was applied to other relationships.

Relationships and social harmony

[edit | edit source]Relationships are central to Confucianism. Particular duties arise from one's particular situation in relation to others. The individual stands simultaneously in several different relationships with different people: as a junior in relation to parents and elders, and as a senior in relation to younger siblings, students, and others. While juniors are considered in Confucianism to owe their seniors reverence, seniors also have duties of benevolence and concern toward juniors. This theme of mutuality is prevalent in East Asian cultures even to this day.

Social harmony—the great goal of Confucianism—therefore results in part from every individual knowing his or her place in the social order, and playing his or her part well. According to Confucius:

- There is government, when the prince is prince, and the minister is minister; when the father is father, and the son is son. (Analects XII, 11)

The perfect person

[edit | edit source]The term jūnzǐ (君子; literally "lord's child") is crucial to classical Confucianism. Confucianism exhorts all people to strive for the ideal of a "gentleman" or "perfect man". A succinct description of the "perfect man" is one who "combines the qualities of saint, scholar, and gentleman." In modern times the masculine translation in English is also traditional and is still frequently used. Elitism was bound up with the concept, and gentlemen were expected to act as moral guides to the rest of society. They were to:

- cultivate themselves morally;

- show filial piety and loyalty where these are due; and

- cultivate humanity, or benevolence

The great exemplar of the perfect gentleman is Confucius himself. Perhaps the tragedy of his life was that he was never awarded the high official position which he desired, from which he wished to demonstrate the general well-being that would ensue if humane persons ruled and administered the state.

The opposite of the jūnzǐ was the xiǎorén (小人; literally "small person"). The character 小 in this context means petty in mind and heart, narrowly self-interested, greedy, superficial, or materialistic.

Rectification of names

[edit | edit source]Confucius believed that social disorder often stemmed from failure to perceive, understand, and deal with reality. Fundamentally, then, social disorder can stem from the failure to call things by their proper names, and his solution to this was Zhèngmíng (正名; literally "rectification of terms"). He gave an explanation of zhengming to one of his disciples:

- Zi-lu said, "The ruler of Wei has been waiting for you, in order with you to administer the government. What will you consider the first thing to be done?"

- The Master replied, "What is necessary to rectify names."

- "So! indeed!" said Zi-lu. "You are wide off the mark! Why must there be such rectification?"

- The Master said, "How uncultivated you are, Yu! A superior man, in regard to what he does not know, shows a cautious reserve.

- If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things.

- If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.

- When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music do not flourish.

- When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded.

- When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot.

- Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect."

- (Analects XIII, 3)

Xun Zi, chapter (22) "On the Rectification of Names," claims the ancient sage-kings chose names (名) that directly corresponded with actualities (實), but later generations confused terminology, coined new nomenclature, and thus could no longer distinguish right from wrong.

Governance

[edit | edit source]To govern by virtue, let us compare it to the North Star: it stays in its place, while the myriad stars wait upon it. (Analects II, 1)

Another key Confucian concept is that in order to govern others one must first govern oneself. When developed sufficiently, the king's personal virtue spreads beneficent influence throughout the kingdom. This idea is developed further in the Great Learning, and is tightly linked with the Taoist concept of wu wei (无为): the less the king does, the more gets done. By being the "calm center" around which the kingdom turns, the king allows everything to function smoothly and avoids having to tamper with the individual parts of the whole.

This idea may be traced back to early Chinese shamanistic beliefs, such as the king being the axle between the sky, human beings, and the Earth. Another complementary view is that this idea may have been used by ministers and counselors to deter aristocratic whims that would otherwise be to the detriment of the state's people.

Meritocracy

[edit | edit source]

In teaching, there should be no distinction of classes. (Analects XV, 39)

The main basis of his teachings was to seek knowledge, study, and become a better person. Although Confucius claimed that he never invented anything but was only transmitting ancient knowledge (see Analects VII, 1), he did produce a number of new ideas. Many European and American admirers such as Voltaire and H. G. Creel point to the revolutionary idea of replacing nobility of blood with nobility of virtue. Jūnzǐ (君子), which originally signified the younger, non-inheriting, offspring of a noble, became, in Confucius' work, an epithet having much the same meaning and evolution as the English "gentleman". A virtuous plebeian who cultivates his qualities can be a "gentleman", while a shameless son of the king is only a "small man". That he admitted students of different classes as disciples is a clear demonstration that he fought against the feudal structures that defined pre-imperial Chinese society.

Another new idea, that of meritocracy, led to the introduction of the Imperial examination system in China. This system allowed anyone who passed an examination to become a government officer, a position which would bring wealth and honour to the whole family. The Chinese Imperial examination system seems to have been started in 165 BCE, when certain candidates for public office were called to the Chinese capital for examination of their moral excellence by the emperor. Over the following centuries the system grew until finally almost anyone who wished to become an official had to prove his worth by passing written government examinations. His achievement was the setting up of a school that produced statesmen with a strong sense of patriotism and duty, known as Rujia (儒家). During the Warring States Period and the early Han Dynasty, China grew greatly and the need arose for a solid and centralized cadre of government officers able to read and write administrative papers. As a result, Confucianism was promoted by the emperor and the men its doctrines produced became an effective counter to the remaining feudal aristocrats who threatened the unity of the imperial state.

During the Han Dynasty, Confucianism developed from an ethical system into a political ideology used to legitimize the rule of the political elites. Most Chinese emperors used a mix of Legalism and Confucianism as their ruling doctrine, often with the latter embellishing the former. The practice of using the Confucian meritocracy to justify political actions continues in countries in the Sinosphere, including post-economic liberalization People's Republic of China, Chiang Kai-Shek's Republic of China, and modern Singapore.

Confucian texts

[edit | edit source]Four Books

[edit | edit source]The Four Books (四書) are Chinese classic texts illustrating the core value and belief systems in Confucianism. They were selected by Zhu Xi in the Song Dynasty to serve as general introduction to Confucian thought, and they were, in the Ming and Qing dynasties, made the core of the official curriculum for the civil service examinations.

| Title (English) | Title (Chinese) | Brief description |

|---|---|---|

| Great Learning | 大学 | It consists of a short main text attributed to the teachings of Confucius and then ten commentary chapters accredited to one of Confucius' disciples, Zengzi. The ideals of the book were supposedly Confucius's; however the text was written after his death. It is significant because it expresses many themes of Chinese philosophy and political thinking, and has therefore been extremely influential both in classical and modern Chinese thought. Government, self cultivation and investigation of things are linked. |

| Doctrine of the Mean | 中庸 | Text attributed to Zisi (also known as Kong Ji), the only grandson of Confucius.. The purpose of this small, 33-chapter book is to demonstrate the usefulness of a golden way to gain perfect virtue. It focuses on the Way (道) that is prescribed by a heavenly mandate not only to the ruler but to everyone. To follow these heavenly instructions by learning and teaching will automatically result in a Confucian virtue. Because Heaven has laid down what is the way to perfect virtue, it is not that difficult to follow the steps of the holy rulers of old if one only knows what is the right way. |

| Analects | 论语 | It is the collection of sayings and ideas attributed to the Chinese philosopher Confucius and his contemporaries. Since Confucius's time, the Analects has heavily influenced the philosophy and moral values of China and later other East Asian countries as well. The Imperial examinations, started in the Jin Dynasty and eventually abolished with the founding of the Republic of China, emphasized Confucian studies and expected candidates to quote and apply the words of Confucius in their essays. |

| Mencius | 孟子 | Commonly called the Mengzi, is a collection of anecdotes and conversations of the Confucian thinker and philosopher Mencius. The work dates from the second half of the 4th century BCE. In contrast to the sayings of Confucius, which are short and self-contained, the Mencius consists of long dialogues with extensive prose. |

Five Classics

[edit | edit source]The Five Classics (五经) are five ancient Chinese books used in Confucianism as the basis of studies. These books, or parts of them, were either commented, compiled, or edited by Confucius himself. They are:

| Title (English) | Title (Chinese) | Brief description |

|---|---|---|

| Classic of Poetry | 詩經 | A collection of 305 poems divided into 160 folk songs, 105 festal songs sung at court ceremonies, and 40 hymns and eulogies sung at sacrifices to gods and ancestral spirits of the royal house. |

| Book of Documents | 尚書 | A collection of documents and speeches alleged to have been written by rulers and officials of the early Zhou period and before. It is possibly the oldest Chinese narrative, and may date from the 6th century BC. It includes examples of early Chinese prose. |

| Book of Rites | 禮記 | Describes ancient rites, social forms and court ceremonies. The version studied today is a re-worked version compiled by scholars in the third century BC rather than the original text, which is said to have been edited by Confucius himself. |

| Classic of Changes | 易經 | Also known as I Ching. The book contains a divination system comparable to Western geomancy or the West African Ifá system. In Western cultures and modern East Asia, it is still widely used for this purpose. |

| Spring and Autumn Annals | 春秋 | Also known as Līn Jīng (麟經), a historical record of the state of Lu, Confucius's native state, 722–481 BCE, compiled by himself, with implied condemnation of usurpations, murder, incest, etc. |

Three Commentaries

[edit | edit source]The Three Commentaries on the Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋三传), are a series of works that annotate the classic Chinese historical text the Spring and Autumn Annals. They comprise:

- The Commentary of Zuo

- The Commentary of Gongyang

- The Commentary of Guliang

Both the Book of Han and the Records of the Grand Historian provide detailed information on the origins of the three texts. Two further commentaries, the Zou Shi Zhuan (鄒氏傳) and the Jia Shi Zhuan (夾氏傳) were known to exist but are now lost.

Thirteen Classics

[edit | edit source]The Thirteen Classics (十三经) is a term for the group of thirteen classics of Confucian tradition that became the basis for the Imperial Examinations during the Song Dynasty and have shaped much of East Asian culture and thought. It includes all of the Four Books and Five Classics but organizes them differently and includes the Classic of Filial Piety and Erya. They are, in approximate order of composition:

- Classic of Changes or I Ching (易經 Yìjīng)

- Book of Documents (書經 Shūjīng)

- Classic of Poetry (詩經 Shījīng)

- The Three Ritual Classics (三禮 Sānlǐ)

- Rites of Zhou (周禮 Zhōulǐ)

- Ceremonies and Rites (儀禮 Yílǐ)

- Book of Rites (禮記 Lǐjì)

- The Three Commentaries on the Spring and Autumn Annals

- The Commentary of Zuo (左傳 Zuǒ Zhuàn)

- The Commentary of Gongyang (公羊傳 Gōngyáng Zhuàn)

- The Commentary of Guliang (穀梁傳 Gǔliáng Zhuàn)

- The Analects (論語 Lúnyǔ)

- Classic of Filial Piety (孝經 Xiàojīng)

- Erya (爾雅 Ěryǎ), a dictionary and encyclopedia

- Mencius (孟子 Mèngzǐ)

Others

[edit | edit source]- Han Kitab (汉克塔布): It is a collection of Chinese Islamic texts, written by Chinese Muslims, which synthesized Islam and Confucianism. It was written in the early 18th century during the Qing dynasty.

- Interactions between Heaven and Mankind (天人感应): It is a set of doctrines formulated by Chinese Han Dynasty scholar Dong Zhongshu which at that time became the basis for deciding the legitimacy of a monarch.

- Old Texts (古文经): It refers to some versions of the Five Classics discovered during the Han Dynasty, written in archaic characters and supposedly produced before the burning of the books, as opposed to the Modern Texts or New Texts (今文經) in the new orthography.

- The Twenty-four Filial Exemplars ( 二十四孝): Also translated as The 24 Paragons of Filial Piety. It is a classic text of Confucian filial piety written by Guō Jūjìng, a scholar of the Yuan dynasty (1260–1368).

Attribution

[edit | edit source]"Confucianism" (Wikipedia) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confucianism