Principles of Biochemistry/Biomolecules

Biochemistry

[edit | edit source]The word "biochemistry" was first proposed in 1903 by Carl Nerg, a German chemisubet. Biochemistry is the study of chemical processes in living organisms. Biochemistry governs all living organisms and living processes. Today the main focus of pure biochemistry is in understanding how biological molecules give rise to the processes that occur within living cells which in turn relates greatly to the study and understanding of whole organisms.

Biomolecules

[edit | edit source]The four main classes of molecules in biochemistry are carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Many biological molecules are polymers: in this terminology, monomers are relatively small micromolecules that are linked together to create large macromolecules, which are known as polymers. When monomers are linked together to synthesize a biological polymer, they undergo a process called dehydration synthesis.

AMINO ACID

Amino acids are natural monomers that polymerize at ribosomes to form proteins. Nucleotides, monomers found in the cell nucleus, polymerize to form nucleic acids – DNA and RNA. Glucose monomers can polymerize to form starches, glycogen or cellulose; xylose monomers can polymerise to form xylan. In all these cases, a hydrogen atom and a hydroxyl (-OH) group are lost to form H2O, and an oxygen atom links each monomer unit. Due to the formation of water as one of the products, these reactions are known as dehydration or condensation reactions.

Conventions and nomenclature

[edit | edit source]

=

Nucleic acids

[edit | edit source]The convention for a nucleic acid sequence is to list the nucleotides as they occur from the 5' end to the 3' end of the polymer chain, where 5' and 3' refer to the numbering of carbons around the ribose ring which participate in forming the phosphate diester linkages of the chain. Such a sequence is called the primary structure of the biopolymer.[1]

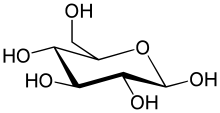

Sugars

[edit | edit source]Sugar polymers can be linear or branched are typically joined with glycosidic bonds. However, the exact placement of the linkage can vary and the orientation of the linking functional groups is also important, resulting in α- and β-glycosidic bonds with numbering definitive of the linking carbons' location in the ring.

Lipids

Lipids are chiefly fatty acid esters, and are the basic building blocks of biological membranes. Another biological role is energy storage (e.g., triglycerides). Most lipids consist of a polar or hydrophilic head (typically glycerol) and one to three nonpolar or hydrophobic fatty acid tails, and therefore they are amphiphilic. Fatty acids consist of unbranched chains of carbon atoms that are connected by single bonds alone (saturated fatty acids) or by both single and double bonds (unsaturated fatty acids). The chains are usually 14-24 carbon groups long, but it is always an even number. For lipids present in biological membranes, the hydrophilic head is from one of three classes: Glycolipids, whose heads contain an oligosaccharide with 1-15 saccharide residues. Phospholipids, whose heads contain a positively charged group that is linked to the tail by a negatively charged phosphate group. Sterols, whose heads contain a planar steroid ring, for example, cholesterol. Other lipids include prostaglandins and leukotrienes which are both 20-carbon fatty acyl units synthesized from arachidonic acid. They are also known as fatty acids.[2]

Amino acids

Amino acids contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. (In biochemistry, the term amino acid is used when referring to those amino acids in which the amino and carboxylate functionalities are attached to the same carbon, plus proline which is not actually an amino acid). Amino acids are the building blocks of long polymer chains. With 2-10 amino acids such chains are called peptides, with 10-100 they are often called polypeptides, and longer chains are known as proteins. These protein structures have many structural and enzymatic roles in organisms. There are twenty amino acids that are encoded by the standard genetic code, but there are more than 500 natural amino acids. When amino acids other than the set of twenty are observed in proteins, this is usually the result of modification after translation (protein synthesis). Only two amino acids other than the standard twenty are known to be incorporated into proteins during translation, in certain organisms: Selenocysteine is incorporated into some proteins at a UGA codon, which is normally a stop codon. Pyrrolysine is incorporated into some proteins at a UAG codon. For instance, in some methanogens in enzymes that are used to produce methane. Besides those used in protein synthesis, other biologically important amino acids include carnitine (used in lipid transport within a cell), ornithine, GABA and taurine.[3]

Protein

The particular series of amino acids that form a protein is known as that protein's primary structure. This sequence is determined by the genetic makeup of the individual. Proteins have several, well-classified, elements of local structure formed by intermolecular attraction, this forms the secondary structure of protein. They are broadly divided in two, alpha helix and beta sheet, also called beta pleated sheets. Alpha helices are formed of coiling of protein due to attraction between amine group of one amino acid with carboxylic acid group of other. The coil contains about 3.6 amino acids per turn and the alkyl group of amino acid lie outside the plane of coil. Beta pleated sheets are formed by strong continuous hydrogen bond over the length of protein chain. Bonding may be parallel or antiparallel in nature. Structurally, natural silk is formed of beta pleated sheets. Usually, a protein is formed by action of both these structures in variable ratios. Coiling may also be random. The overall 3D structure of a protein is termed its tertiary structure. It is formed as result of various forces like hydrogen bonding, disulfide bridges, hydrophobic interactions, hydrophilic interactions, van der Waals force etc. When two or more different polypeptide chains cluster to form a protein, quaternary structure of protein is formed. Quaternary structure is a unique attribute of polymeric and heteromeric proteins like hemoglobin, which consists of two alpha and two beta peptide chains.[4]

Like carbohydrates, some proteins perform largely structural roles. For instance, movements of the proteins actin and myosin ultimately are responsible for the contraction of skeletal muscle. One property many proteins have is that they specifically bind to a certain molecule or class of molecules—they may be extremely selective in what they bind. Antibodies are an example of proteins that attach to one specific type of molecule. In fact, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which uses antibodies, is currently one of the most sensitive tests modern medicine uses to detect various biomolecules. Probably the most important proteins, however, are the enzymes. These molecules recognize specific reactant molecules called substrates; they then catalyze the reaction between them. By lowering the activation energy, the enzyme speeds up that reaction by a rate of 1011 or more: a reaction that would normally take over 3,000 years to complete spontaneously might take less than a second with an enzyme. The enzyme itself is not used up in the process, and is free to catalyze the same reaction with a new set of substrates. Using various modifiers, the activity of the enzyme can be regulated, enabling control of the biochemistry of the cell as a whole.[5]

In essence, proteins are chains of amino acids. An amino acid consists of a carbon atom bound to four groups. One is an amino group, —NH2, and one is a carboxylic acid group, —COOH (although these exist as —NH3+ and —COO− under physiologic conditions). The third is a simple hydrogen atom. The fourth is commonly denoted "—R" and is different for each amino acid. There are twenty standard amino acids. Some of these have functions by themselves or in a modified form; for instance, glutamate functions as an important neurotransmitter.

Amino acids can be joined together via a peptide bond. In this dehydration synthesis, a water molecule is removed and the peptide bond connects the nitrogen of one amino acid's amino group to the carbon of the other's carboxylic acid group. The resulting molecule is called a dipeptide, and short stretches of amino acids (usually, fewer than around thirty) are called peptides or polypeptides. Longer stretches merit the title proteins. As an example, the important blood serum protein albumin contains 585 amino acid residues.[6]

The structure of proteins is traditionally described in a hierarchy of four levels. The primary structure of a protein simply consists of its linear sequence of amino acids; for instance, "alanine-glycine-tryptophan-serine-glutamate-asparagine-glycine-lysine-…". Secondary structure is concerned with local morphology (morphology being the study of structure). Some combinations of amino acids will tend to curl up in a coil called an α-helix or into a sheet called a β-sheet; some α-helixes can be seen in the hemoglobin. Tertiary structure is the entire three-dimensional shape of the protein. This shape is determined by the sequence of amino acids. In fact, a single change can change the entire structure. The alpha chain of hemoglobin contains 146 amino acid residues; substitution of the glutamate residue at position 6 with a valine residue changes the behavior of hemoglobin so much that it results in sickle-cell disease. Finally quaternary structure is concerned with the structure of a protein with multiple peptide subunits, like hemoglobin with its four subunits. Not all proteins have more than one subunit.[7]

Ingested proteins are usually broken up into single amino acids or dipeptides in the small intestine, and then absorbed. They can then be joined together to make new proteins. Intermediate products of glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and the pentose phosphate pathway can be used to make all twenty amino acids, and most bacteria and plants possess all the necessary enzymes to synthesize them. Humans and other mammals, however, can only synthesize half of them. They cannot synthesize isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine. These are the essential amino acids, since it is essential to ingest them. Mammals do possess the enzymes to synthesize alanine, asparagine, aspartate, cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, and tyrosine, the nonessential amino acids. While they can synthesize arginine and histidine, they cannot produce it in sufficient amounts for young, growing animals, and so these are often considered essential amino acids. If the amino group is removed from an amino acid, it leaves behind a carbon skeleton called an α-keto acid. Enzymes called transaminases can easily transfer the amino group from one amino acid (making it an α-keto acid) to another α-keto acid (making it an amino acid). This is important in the biosynthesis of amino acids, as for many of the pathways, intermediates from other biochemical pathways are converted to the α-keto acid skeleton, and then an amino group is added, often via transamination. The amino acids may then be linked together to make a protein.[8]

A similar process is used to break down proteins. It is first hydrolyzed into its component amino acids. Free ammonia (NH3), existing as the ammonium ion (NH4+) in blood, is toxic to life forms. A suitable method for excreting it must therefore exist. Different strategies have evolved in different animals, depending on the animals' needs. Unicellular organisms, of course, simply release the ammonia into the environment. Similarly, bony fish can release the ammonia into the water where it is quickly diluted. In general, mammals convert the ammonia into urea, via the urea cycle.[9]

Vitamins A vitamin is a compound that is generally not synthesized by a given organism but is nonetheless vital to its survival or health (for example coenzymes). These compounds must be absorbed, or eaten, but typically only in trace quantities. When originally proposed by Casimir Funk, a Polish biochemist, he believed them to all be basic and therefore named them vital amines. The "l" was later dropped to form the word vitamines.[10]

==>http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Terpene&oldid=418364359</ref>

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biopolymer&oldid=424420208

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biomolecule&oldid=420100572

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biomolecule&oldid=420100572

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biomolecule&oldid=420100572

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biomolecule&oldid=420100572

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biomolecule&oldid=420100572

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biomolecule&oldid=420100572

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=History_of_biochemistry&oldid=421973684

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biomolecule&oldid=420100572

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biomolecule&oldid=420100572