Planet Earth/5d. Ocean Circulation (Surface and Deep).

An Ill Fated Expedition to the North Pole

[edit | edit source]

Encased in ice, the American ship Jeannette was being crushed, its wooden hull cracking and breaking under the intense cold grip of the frozen ocean. For the past month, the ship had been entrapped in the arctic ice. The crew scrambled as they off-loaded boats onto the flat white barren landscape. They dragged the boats with them, as they watched with horror the splintered remains of the ship sink between the icy cavasses of the frozen Arctic ocean. The expedition was headed toward the North Pole, led by their captain George W. De Long, a United States Navy officer who was on a quest to find passage to the open northern polar sea. His ship sinking beneath the ice, left his crew isolated upon the frozen ocean. De Long took out his caption log book, and listed the location of the sinking ship, latitude 77°15′ North longitude 155°0′ East, before ordering the men to drag the boats and whatever provisions they had remaining across the vast expanse of ice.

Once they reached open water, they set their boats into the non-frozen waters and rowed southward. Chief Engineer George Melville, a stoic figure with a long prophetic beard, lead one group of survivors. Melville had worked his way up in the Navy, helping to establish the United States Naval Academy, was a veteran of such dangerous Arctic explorations. In 1873, he volunteered to help rescue the survivors of the ill-fated Polaris expedition, an attempt to reach the North Pole. Now trapped in a similar situation George Melville watched as the various boats were tossed on the open water and soon became separated in the night. It was the last time he would see Captain De Long, alive. His small crew on the boat would survive after landing on the shores of the Lena Delta on the northern coast of Siberia. For the next year, Melville searched for De Long, and finally discovered his body, and those of 11 crew men. He also found the captain’s log book that recorded their furthermost approach to the North Pole. Melville wrote of the ill-fated expedition, and the search for the Captain in a book published in 1884.

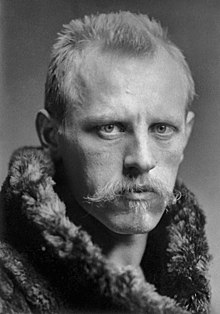

That same year, 1884, the wreckage of their ship was discovered off the coast of Greenland. The ship despite sinking in the ice north of Siberia, had somehow traveled across the Arctic ocean carried by the polar ocean currents to Southern Greenland, thousands of miles away. The long voyage of this wreckage, sparked an idea for another attempt to reach the North Pole by the Norwegian explorer Fridtjor Nansen to purposely sail a steamship into the ice, and let the ice carry the vessel as close as possible to the North Pole. Once the trapped ship reached the furthermost distance north in the ice, a dog sled team could disembark from the ice encased ship, and travel the remaining miles over frozen sea ice to reach the northernmost point on Planet Earth. It was a daring plan, that required knowledge of the motion of ocean currents and sea ice in the high arctic.

The steamship Fram sailed from Norway following the coast of northern Siberia, then looped back heading northward until it encountered the ice. For three years the ship was carried on its northward then westward journey trapped and encased in ice, when it reached its most northern point on March 14 1895, Fridtjor Nansen and Hjalmar Johansen disembarked from the ice trapped ship, and headed even further north by dog sled. Nansen would record a northern latitude of 86°13.6′ North on his sexton, before turning back, unable to reach the north pole at 90° N. Over the next year the two men traveled southward over the sea ice, and miraculously both men would survive the journey. The ice trapped steamship and its crew was released from the ice and was able to sail back successfully to Norway. No crew member died with the attempt, and despite not reaching the North Pole, the expedition was viewed as an amazing success. A marine zoologist by training, Nansen returned home and dedicated himself to studying the ocean.

How Ocean Currents Move Across Earth

[edit | edit source]

Fridtjor Nansen remained puzzled how ocean currents move across Earth. He was particularly interested in how icebergs and stranded ships are carried by the ocean. During the expedition, Nansen utilized the Transpolar drift an ocean current that flows from the coast of Siberia westward toward Greenland, driven by a large circular current called the Beaufort Gyre, that encircles the North Pole. In oceanography, a gyre is a large circulating ocean surface current. The Beaufort Gyre spins clockwise around the North Pole, while Earth spins in a counterclockwise direction around the polar axis. Nansen reasoned that the reason the surface of the ocean spins in the opposite direction to the Earth is that unlike the solid earth, the liquid ocean (and the atmospheric gas above) are only loosely attached to the surface of the Earth, the inertia of the Earth’s rotation and drag, causes the liquid to trail or lag behind the motion of the solid Earth. When Nansen’s ship was trapped in the sea ice, the Earth rotated around below the ship, while the liquid ocean, carrying the frozen sea ice and trapped ship appeared to resisted this motion, and hence the coast of Greenland was brought toward the ship, as the solid Earth rotated below it. However, Nansen realized that this was not true, since the ocean and solid earth travel around the axis at nearly the same constant velocity and same inertia. The ice and ocean currents should rotate in-sync with the rotating Earth. During the expedition, Nansen noticed that ice drifted at an angle between 20° to 40° to the right of the prevailing wind direction, he suspected that the ocean currents were influenced by prevailing wind directions instead.

Nansen contacted Professor Vilhelm Bjerknes at the University of Uppsala, who was studying fluid dynamics. Bjerknes thought the ocean currents were largely controlled by the Coriolis force arising from the motion of the Earth, but suggested that his brightest student, Vagn Walfrid Ekman undertake the study for his doctoral research. Ekman was the opposite of the rugged Arctic explorer Nansen. Ekman was studious with thick eye glasses and a petite gentle frame. He was more comfortable with mathematic equations and played the piano and sing in a local choir.

Fluid dynamic experiments carried out with rotating bowls of water at a constant velocity showed that spinning the bowl (with zero acceleration), there was a stabilizing effect when drops of colored dye were added to the water from above. This is because the point or location the dye was added to a spinning bowl of water had the same speed and same inertia as the spinning bowl beneath it. In fact, the color from the dye was observed to form a narrow column, and not rotate in relation to the spinning bowl beneath. This seemed to suggest that the Arctic exploring feat of Nensen was an impossibility. However, if dye was added to the spinning bowl of water from the side, the dye would quickly spiral due to the Coriolis effect, as the dye was moving across different radii, and hence its velocity was changing due to this horizontal motion.

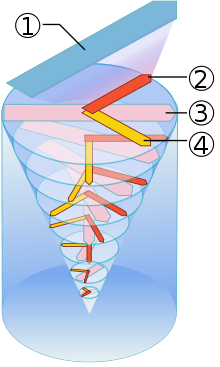

Ekman suspected that in the open ocean there was various forces working to change the velocity or speed of the ocean water that would destabilize the water and result in its motion. Ekman defined two boundaries, known as Ekman Layers, the first of which is the ocean floor. The ocean floor is not flat, but has a complex topography, this boundary is the most rigid as it is under the most pressure from water above. The second Ekman Layer is the ocean’s surface. Here the ocean is affected by blowing wind, and is under the least amount of pressure. The prevailing wind would be governed by geostrophic flow, that is affected by a balance between atmospheric pressure gradients, and the Coriolis force; these geostrophic winds tend to travel parallel to an air pressure gradient. Wind would only affect the upper most portion of the ocean, maybe only to depths of 10 meters. This pressure gradient between the two Ekman Layers of the ocean results in changes in velocity between each layer, resulting a shearing of the liquid ocean, as the upper part is influence by the wind direction and the lower part is influence by the rotating Earth. Using mathematical formulas, Ekman demonstrated that this motion would result in a spin or spiral motion within the ocean, known as the Ekman Spiral.

At the surface of the ocean, the direction of horizontal motion would be greatest, because of the influence of geostrophic winds on the ocean surface. The geostrophic winds would drive the ocean water below them to flow perpendicular to the Coriolis direction, however, since the water is not influenced by the air pressure gradient, they will be more effected by the Coriolis direction resulting in a current that is at an angle between 20° to 40° to the right (in the Northern Hemisphere) of the prevailing wind direction. The Ekman Spiral, and the mathematics that Ekman developed allowed a profound understanding of the motion of ocean currents.

The Ekman Spiral has several important implications. First is that surface, or near surface ocean waters move the quickest, while deep ocean waters are much less mobile, and are more permanently fixed to the ocean floor. Oceanographers describe the motion of ocean water circulation across the Earth into two very different patterns. Those of surface ocean circulation are much more mobile, with surface ocean water circulating across the planet very quickly (a few months to several years), while deep ocean circulation is much slower, with long term patterns of deep-water circulation lasting hundreds or thousands of years. The Ekman Spiral also demonstrated how Nensen’s daring expedition was able to be successful, since the ship was trapped in sea ice at the surface, it was affected by the prevailing geostrophic easterly winds that blow across the Transpolar drift, in addition to the Coriolis Effect spinning the Beaufort Gyre in a clock-wise direction. This resulted in surface ocean waters and sea ice to travel at an 20° to 40° angle to the prevailing wind direction, and resulted in Nensen’s near successful attempt at reaching the north pole.

Upwelling and Downwelling

[edit | edit source]

Ekman’s spiral is useful in understanding how ocean water can move vertically through the water column, especially within ocean water near coastlines along the continental margins. This upwelling and downwelling occurs when wind directions drive ocean currents either toward or away from the coastline. If the prevailing wind is blowing and results in surface ocean currents that move from the ocean toward the land and these surface ocean currents are perpendicular to the coastline, the surface ocean waters will result in a downwelling of ocean waters, as the ocean water is pushed deeper when it reaches the coast. However, when the prevailing wind is blowing from land out across the ocean and the surface ocean current is perpendicular to the coastline in the opposite direction, upwelling occurs, as the surface ocean water will be pushed away from coastline, bringing up deeper ocean water to the surface. Often however, the prevailing surface ocean currents are not simply perpendicular to the coastline, resulting in a flow of water called a Longshore Current. Longshore currents depend on a prevailing oblique wind direction that transports water and sediments, like beach sand along the coast parallel to the shoreline. When longshore currents converge in opposite directions, or there is a break in the waves, a Rip Current will form that moves surface ocean water away from the shore and out to sea. Rip currents are dangerous to swimmers, since the strong currents will carry unsuspecting swimmers away from the shore. It is important to note that the upwelling and downwelling of ocean water resulting from Ekman’s research is relatively shallow across the entire ocean, and occurs mostly along the shallow coastlines of islands and continents. The deepest ocean waters in the Abyssal Zone require a different mechanism to raise or lower these deep ocean waters to the surface, which will be discussed later. However, the discoveries and mathematical models of Ekman are important in understanding surface ocean circulation around the world.

Surface Ocean Circulation

[edit | edit source]

Surface ocean circulation in the Northern Hemisphere will spin toward the right in a clockwise direction, while in the Southern Hemisphere surface ocean currents will spin toward the left in a counter-clockwise direction. One of the most well-known surface ocean currents is the Gulf Stream, which extends from the West Indies, through the Caribbean, north along the eastern Coast of the United States and Canada, and brings warm equatorial ocean waters to the British Isles and Europe. The Gulf Stream is part of the larger North Atlantic Gyre, which rotates in a large clock-wise direction in the Northern Atlantic Ocean. The Gulf Stream brings warm ocean waters to the shores of Western Europe, resulting in a warmer climate for these regions. The Canary Current, which travels southward from Spain off the coast of Africa, results in colder surface ocean waters traveling toward the equator, where currents meet the North Equatorial Current completing the full circuit of the North Atlantic Gyre. In the Southern Atlantic Ocean, the surface ocean current rotates in a counter-clockwise direction. Traveling west along the southern equatorial current, then south along the coast of Brazil, east crossing the South Atlantic, and then north along the coast of the Namibian Coast, in a counter-clockwise circuit, as the Southern Atlantic Gyre. The center of both the Northern and Southern Atlantic Gyre, surface ocean currents remain fairly stagnant. Early sailors refer to the center of the Northern Atlantic Gyre as the Sargasso Sea, named because of the abundance of brown seaweed of the genus Sargassum floating in the fairly stagnant ocean waters. Today these regions of the North and South Atlantic Ocean are known by a much more ominous name, the garbage patch. Plastics and other garbage dumped into the oceans accumulate in these regions of the ocean, where they form large floating masses of microplastic polyethylene and polypropylene which make up common household items which have been dumped and carried out into the oceans.

Between the Northern and Southern Atlantic Gyre is a region that sailors historically referred to as the doldrums, which is found along the equatorial latitudes of the Atlantic Ocean. Here surface ocean waters are not as strongly affected by the Coriolis force, because the ocean water is carried in the same direction as the rotation of the Earth. This results in what is known as the Equatorial Counter-Current. The equatorial counter-current carries surface ocean waters from the west to the east, in the opposite direction as the easterly trade winds that carry sailors from the east toward the west near the equator. The equatorial counter-current is a result of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) winds which form a low-pressure converging zone as atmospheric air rises due to the increase in heat from the sun in these warm waters.

Sailing ships avoid these regions, as they can significantly slow the progression of sailing ships dependent on surface ocean currents and prevailing winds. Sailors traveling from Europe to North America follow the easterly trade winds north of this zone, while returning sailors traveling back to Europe following the westerly trade winds of the Gulf Stream, crossing the Northern Atlantic Ocean more north than their voyage to North America. This resulted in early trade routes across the Atlantic following the coast from the West Indies north toward New York, resulting in goods being transported from the south to the north along the Eastern ports of North America. While the Caribbean Islands were some of the first places European and African traders arrived at in the North Hemisphere after traversing the Atlantic Ocean. Ships today are less influenced by surface ocean currents and prevailing winds with engines that drive propellers under the ships. However, surface ocean currents do determine the flow of lost cargo from ships, and are useful for rescuing stranded sailors who are at the mercy of the ocean and its currents.

The Pacific Ocean mirrors the surface ocean currents of the Atlantic, but is at a much larger scale. Similarly, there are two large gyre. In the North Pacific, the North Pacific Gyre is a flow of surface ocean currents that follows a clock-wise direction. With warm equatorial waters moving northward along the Asian coasts, into Korea and Japan, the Kuroshio Current. This current, like the Gulf Stream is a warm current moving northward, the current passes over the North Pacific, before flowing toward the south along the Western Pacific Coast of North America, where it is known as the Californian current. This motion of warm equatorial water across the North Pacific results in a similar warming along the northern coastline of North America. It also moves floating debris from the coast of Japan to the Pacific Northwest coasts of Canada and the United States. Although because the Pacific Ocean is larger than the Atlantic Ocean, the ocean water has cooled slightly. Nevertheless, this Pacific Northwest surface ocean water is warmer than would normally be expected at such high latitudes. For example, the average annual temperature in Vancouver, Canada at latitude 49.30° North is 11.0 °C, while Halifax, Canada (along the North Atlantic Coast) at latitude 44.65° North is just 6.5 °C, despite its more comparatively southern latitude. These warm surface ocean currents may have left much of the North Pacific Coast of North America ice free during past Ice Ages, when large ice sheets covered the interior of Canada. The now cooling waters move southward along the Pacific Coast of the United States resulting in cooler, more temperate climates for Southern California, then would be expected given the more southern latitude of cities like Los Angeles. Surface Ocean Currents have a profound effect on local climates.

The South Pacific Gyre spins in the opposite direction as to the north, in a counter-clockwise direction. This results in warm equatorial ocean surface currents to flow into South Australia and off the coast of New Zealand, bringing warm water to these regions. The East Australian current, like the Kuroshio and Gulf Stream warms these regions, including the Great Barrier Reef southward into Sydney Harbor. The surface ocean circulation then transverses the South Pacific, but cools as it is pushed along the Antarctic Circumpolar current, the Peru current brings cold waters along the western coast of South America, clear up toward the Galápagos Islands. Despite the equatorial latitude, the waters off the Galápagos Islands are relatively cool compared to other equatorial ocean waters due to this cooler Peru current. Penguins occupy the rocky shore line of the islands, at their most northward range. Just like in the Atlantic Ocean, a large Equatorial Counter Current flows toward the east within the ITCZ zone, producing doldrums in the Pacific as well.

The Indian Ocean, unlike the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans is mostly south of the equator, and hence only has one large surface ocean gyre that rotates in the counter-clockwise direction. There is an Equatorial Counter-Current that flows toward the east off the southern coast of India, as a result of the ITCZ zone. This zone shifts northward over the Indian Subcontinent annually, producing the Indian Monsoonal rains each year. East Africa and Madagascar enjoy warmer tropical ocean currents similar to the Gulf Stream, Kuroshio, and East Australian Currents, making these regions also susceptible to typhoons and hurricanes.

The last surface ocean current is by far one of the most important: the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, also known as the West Wind Drift, which encircles the coast of Antarctica. Most of the currents we have discussed are a product of the rotation of the Earth, as well as the arrangement of the continents, which block the motion of the ocean toward the east, resulting in the many gyre discussed above. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current flows toward the east, and because there is no major landmass in its path, continues this flow in perpetuity, always encircling the coast of Antarctic. These ocean waters remain cold, bitterly so compared to other ocean currents, because surface ocean currents don’t loop toward warmer equatorial regions of the planet.

The advent of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current occurred at the beginning of the Oligocene Epoch, 33.9 million years ago, when the Drake Passage that separates South America and Antarctic opened, allowing ocean currents to flow between the two continents, and preventing cold Antarctic ocean waters to be conducted northward. Instead, from this point onward, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current significantly cooled Antarctica, resulting in massive ice sheets to form on the continent, and making it the inhospitably cold place that it is today. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current had a global effect on the planet, resulting in cold global temperatures that lead to the beginning of the Great Ice Ages. Millions of years prior to this event, a no longer existing Global Equatorial Current existed, which passed between North and South America, and extending through the ancient seaway known as the Tethys that separated Africa and Europe and covered the Middle East. This current at the equator, resulting in some of the warmest global climates for Earth during the Eocene Epoch around 50 million years ago. Surface ocean currents have a major effect on regional and global climate, because they are a way, through convection, to bring warm and cold ocean water to different parts of the Earth’s surface.

Density, Salinity and Temperature of the Ocean

[edit | edit source]Density is a measure of the substance’s mass per unit volume, or how compacted or dense a substance is. Specific density is a measure of whether a substance will float or sink relative to pure water, which has a specific density of 1. Liquids with a specific density less than 1 will float, while liquids with a specific density of more than 1 will sink in a glass of pure water. Ocean water, because it contains a mixture of salts and dissolved particles averages a specific density between 1.020 to 1.029. Density in ocean water is measured using a hydrometer, which is a glass tube with a standard weight attached to a scale that indicates how far the weight sinks in the fluid. If you were to mix ocean water and freshwater, the two would likely mix, making it difficult to determine whether one floats above another. The greater density difference between fluids, the more likely you can get them to stack on top of each other, by floating the less dense fluid on top of the denser fluid. However, if you try to stack the denser fluid on top of a less dense fluid, the two fluids simply mix. A column of fluids of different densities is said to be stratified, strata means layers, so a stratified ocean is an ocean that is divided into unique layers based on differences in densities.

The density of water is not only related to how much salt is dissolved in the water, but also the water’s temperature. The colder the water, the denser it becomes, although between 4° C to 0° C near the freezing point water becomes less dense as it freezes to ice.

The gradient between density and salinity of ocean water is called the halocline. In a vertical profile of the ocean, salinity increases with depth, because salty water is denser and will sink. The gradient between density and temperature of ocean water is called the thermocline. In a vertical profile of the ocean, temperature decreases with depth, as colder water (above 4°C) is denser and will sink. The densest ocean water is both cold and salty, while the least dense ocean water is both hot and fresh. The gradient of density with depth is referred to as the pycnocline. Pycnos in ancient Greek means dense. The pycnocline is a graph showing density with depth of ocean water. If the ocean is stratified into layers of different densities, the graph will show a slope with steps at each layer of increasing density. However, if the ocean is well mixed, the pycnocline will be a straight line vertical of equal density with depth. In the previous sections, surface ocean currents and upwelling and downwelling are influenced by geostrophic winds, and surface processes that result in in shallow movement of the ocean waters. However, Ekman’s research also showed that deep ocean water, deeper than 100 meters will remain less mobile, and will not be influenced by these forces that work only on the surface of the ocean. Deep ocean water moves very slowly, so slowly that oceanographers debate what the rate of movement of this deep ocean water truly is as it moves around the Earth.

Deep ocean water circulation of the planet is a slow and gentle process that involves most of the total volume of the oceans, and is a consequence of dynamic changes in ocean water density with depth. Such changes in density result in a mixing of surface and deep ocean waters.

How do oceans or for that matter any large body of water on Earth become stratified into different layers of density? Imagine a large lake, which serves as a reservoir of water with inflowing rivers of fresh salt-free water. The flux of incoming freshwater into the lake from the surrounding rivers decreases in the late summer, but increases in the late winter and early spring from run off or the rainy seasons. During the summer the hot sun heats the top layers of the lake resulting in evaporation, and the underlaying layers of water become saltier, but remain warm. Over time such a lake will become stratified into different layers of density. In the summer, the surface water will become salty, but warmer, allowing it to float over the denser water below, however, as the fall temperatures drop, the salty water will increase in density. During the spring an influx of less dense freshwater from the rivers will float over this salty and colder water already in the lake. This adds a new layer of less dense freshwater, and stacks the water on top. Over time, the lake will become heavily stratified into cold/salty dense layers remaining deep in the lake, while warm/fresh less dense water remain at the top with each input of freshwater.

What process can cause the two layers to mix? If during the winter months the lake is covered in ice, the top layer of water will become both cold and salty. The salt originates from the fact that as ice forms on the top of the lake, the ice will contain no salts, leaving the layers just below the ice slightly saltier, and very cold. Ice coverage on the lake will cause this salty/cold dense water to lay on top of warm/fresh less dense water, which will ultimately cause the water at the surface to sink, and the deep water to rise. An ice-covered body of water contains a better mixture of waters compared to ice-free bodies of water. As a result, bodies of water in cold regions of Earth are less stratified than waters in warm tropical regions. Another thing that can happen to the lake is if the deep water is somehow warmed. This can occur when a volcano or magma heats the bottom waters. When these dense deep waters are heated, they become less dense and rise, this is likely what happened in the Lake Nyos disaster in Cameroon Africa, when deep waters bubbled up releasing massive amounts of carbon dioxide gas killing many people.

Measurements of the pycnocline in various lakes around the world demonstrate that colder lakes covered in ice during the winter are better mixed than warmer lakes, which remain ice free. The same processes of mixing deep waters with surface waters can be applied to the entire ocean, which is more complex since the Worlds Ocean is more interconnected and spans the entire Earth’s surface. Oceanographers have mapped out differences in annual temperatures and salinity to help to understand this complex process.

Annual surface temperatures measured across the entire ocean show that the warmest waters are found along the equator, with the coldest waters found near the poles. However, surface salinity measured across the entire ocean shows that the saltiest surface waters are found within the large ocean gyres, such as the North Atlantic and South Atlantic gyres, which are some of the saltiest regions of the open ocean. This is because these regions of the ocean are more stagnant, as well as being in drier regions that receive less rainfall. The ITCZ zone around the equator contributes massive amounts of freshwater from rain, and limits evaporation along the equator. Large confided bodies of ocean water surrounded by land, like the Mediterranean and Red Seas, are some of the most saline regions of the ocean. Some of the least salty regions of the ocean are found near where there is a large input into the ocean of freshwater from rivers, particularly in Southeastern Asia. Regions near the poles also get input of freshwater from melt waters. Sea ice which expands during the winter months in polar regions of the Arctic and Antarctic Oceans is important for the mixing of surface and deep ocean waters. If these waters are already salty from evaporation, mixing can be enhanced. In the North Atlantic the salty surface ocean waters trapped in the North Atlantic gyre are pushed northward toward Greenland with the Gulf Stream currents. If these salty warmer waters are subsequently cooled and covered in sea ice, these waters will sink, resulting in a mixing of surface and deep waters in the North Atlantic Ocean. This drives what is called the Thermohaline circulation of deep ocean waters. The Thermohaline circulation is a broad deep water circulation of the entirety of the world’s ocean, although the precise process of this motion is highly debated among oceanographers. The North Atlantic serves as the region of sinking cold salty water, resulting from salty water in the Atlantic pushed northward, and subjected to coverage of sea ice, especially during the winter months in the Northern Hemisphere. This sinking cold salty ocean water churns the ocean over in the North Atlantic and helps to drive the Gulf Stream, pulling more warm salty waters northward to cool and subsequently sink. The North Atlantic is the least stratified region in the worlds ocean, resulting in well-mixed waters that are enriched in oxygen.

Ice core from Greenland records a period of time 12,000 years ago, when the Thermohaline circulation may have been altered dramatic. This period of time is called the Younger Dryas event, because sediments in lakes record the return of pollen of the cold-adapted Dryas arctic flower, which prefers colder climates. The flower grew across much of Northern Europe and Greenland during the last Ice Age up to about 14,000 years ago, when the flower disappeared from these regions as the climate warmed. However, the flower’s pollen returns in the sediments of lakes around 12,000 years ago, signaling a return of cold climates for several hundred years, before again disappearing from these regions. This episode of colder climates in the North Atlantic is hypothesized to be a result of the thermohaline circulation being altered by an influx of freshwater from land. The idea holds that massive amounts of freshwater flooded into the North Atlantic, particularly from the Labrador Sea and Straits of Lawrence, which drained the great ice sheets that covered the Great Lakes and much of Canada. This influx of freshwater resulted in the North Atlantic Ocean becoming more stratified, and resulted in weakening Gulf Stream, with less warm ocean water reaching Northern Europe. This resulted in colder climates to prevail, until the melt of the great ice sheets ended, as which time the Thermohaline circulation resumed, resulting in warmer climates in Northern Europe again. The thermohaline circulation is often depicted as a ribbon of flow that involves the entire world’s ocean, but oceanographers debate how this circulation pattern works in reality on a global scale. Recent research suggests that the deep ocean waters that encircle Antarctica are pulled up as a result of this churning in the North Atlantic. These Southern Ocean waters are warmest during December/January and rise with the warming temperatures, pulled by the North Atlantic which is at its coldest and saltiest levels during these months. In July/August, the North Atlantic Ocean returns to its warmest levels, while the ocean waters around Antarctica are at their coldest and covered by sea ice. Polynyas form in the sea ice around Antarctica, which are regions of thin ice mix with open water which are thinner than expected for the given temperature, because these regions frequently contain saltier water. This results in the cold/salty water to sink deeper around the coast of Antarctica in July/August. Like a teeter-totter, deep ocean water circulating around Antarctica rises and falls each year with the seasons. These Antarctic Bottom Waters are well mixed, and enriched in oxygen and nitrogen. Sea ice is of vital importance in the mixing of the World’s Oceans, and life has adapted to the annual rise and fall of deep ocean waters in these polar regions. When deeper ocean waters rise in these polar regions, they bring up nitrogen which benefits phytoplankton growing in the upper photic zone. Large blooms of phytoplankton occur during the summer months, which attract krill and fish that feed on the phytoplankton. These schools of fish and krill prosper in the oxygen enriched cold waters, and feed migrating baleen whales, which feed on the krill using baleen to filter them out of the water. The largest animal on Planet Earth, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) evolved to exploit the deep ocean circulation patterns that have result from large portions of the ocean being covered in sea ice.

There have been periods of time that Earth’s ocean remained ice free, particularly during periods of enriched carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Deep ocean water mixing without sea ice formation is possible, and occurs when salty water from warm seas that are confined and subjected to enhanced evaporation enter colder open ocean waters. An example of where this happens is near the Straits of Gibraltar where the salty warm waters of the Mediterranean enter into the colder Atlantic Ocean. Heat diffuses faster than salt, and the relatively faster transfer of heat compared to salt results in the salty water cooling more quickly than the salt can disperse, and hence becomes unstable near the surface of the ocean. This salty/cold water is denser and sinks, forming “salt fingers,” which are a mix of deep and surface waters churning the waters vertically. These regions are enriched in nitrogen, phosphorus, as well as being fairly well oxygenated ocean waters. During Earth’s long history, such regions where responsible for biologically rich ocean life, despite periods of time when the oceans remained ice free year-round. One example of this is found in the rocks of Eastern Utah. During the Pennsylvania and Permian Periods about 270 million years ago, a land-restricted sea existed in present day Moab, which was extremely salty, but opened out into the larger open ocean to the northwest. The influx of salty water from this sea resulted in a well-mixed ocean despite the much warmer climate of the time. Fossils are found abundantly in marine rocks of this age, as well as thick deposits of phosphorus mined for agricultural fertilizers.

If the Earth’s oceans remain ice-free year-round, and there is no influx of salty surface waters from land-restricted seas, like the Mediterranean Sea, then the oceans can quickly become highly stratified. A highly stratified ocean means that deep and surface ocean waters never mix, and oxygen levels become highly restricted to only the surface of the ocean. Such periods of time happened on Earth, particularly during the Mesozoic Era, when dinosaurs roamed a much warmer Earth. These oceans are prone to anoxia, the absence of oxygen, which results in “dead zones” where fish and other animals that need oxygen for respiration perish. An example of ocean water that is susceptible to anoxia is the Gulf of Mexico. During the heat of the late summer, the surface waters in the Gulf of Mexico evaporate resulting in salty surface waters, which sink as winter begins, but remains ice-free. The spring brings large amounts of freshwater from the Mississippi River, which floats on top of the denser ocean water, resulting in a highly stratified ocean. Deep ocean waters in the Gulf of Mexico often lack oxygen because they can’t mix with the surface ocean water (and oxygen atmosphere), and these deep anoxic waters remained locked deep in the basin of the Gulf of Mexico, with the annual influx of spring freshwater and evaporation in late summer warm temperatures.

Catastrophic Mixing of Deep and Surface Ocean Waters

[edit | edit source]In 1961, James P. Kennett raced across the mountainous landscape of the South Island of New Zealand on a motorcycle on a mission. He was searching for rocks. Ever since he was a child growing up in Wellington New Zealand, Kennett was collecting rocks, shells and fossils from the beaches and mountains of New Zealand. At 18 he went off to college, having learned all he could about the field of geology from books, but since the subject was not offered at his local school he was eager to learn more at the university. Once enrolled in college classes, he begun working in the geology laboratory at the age of 18. Unlike a biology or chemistry lab, a geology lab is a messy dirty place, where rocks are sliced and cut on saws; boxes of heavy rocks collect dust in cases and drawers; lab coats and beakers are replaced with rock grinners, hammers and chisels. Kennett became interested in tiny marine fossils known as foraminifera, which are studied from either sliced or grounding up rocks. Foraminifera are single celled organisms that live on the ocean floor by feeding on organic detritus that sinks down from the photic zone. They form their protective outer skeleton or shell (test) from calcium carbonate. As common fossils, these tiny fossils accumulate thick deposits on the ocean floor that form marine limestones. Limestones such as those used to build the Pyramids in Giza are actually filled with fossils of these single celled animals. Each rock sample could yield thousands of these tiny fossils, and reveal important clues about the ocean in the past, such as temperature, salinity, acidity, and water depth over long periods of time. As Kennett zoomed down the winding roads of New Zealand, he was on a quest to collect marine deposited rocks that bracket the time of the major climate transition that led to the formation of the great ice sheets in Antarctica. With its close proximity to Antarctica, New Zealand was a good place to study this changing climate, and its effects on the ocean in the ancient marine rocks that now eroded out of the mountains. Kennett was young, and not yet even a graduate student, yet his experiences in the lab made him see the world completely differently. He was eager for his own research, and spent his days hunting new rocks from new periods of time documenting the expansion of the Antarctic sea ice during the late Miocene Epoch. His enthusiasm got the attention of his mentors and instructors and was invited to join the crew of the Victoria University of Wellington Antarctic Expedition in 1962-1963. The expedition was to map the frozen Transantarctic Mountain range south of the Ross Sea and collect rock samples. For Kennett the expedition changed his life, but he continued to documented how changes in the ocean over millions of years resulted in an inhospitable cold climate for Antarctic that he experienced firsthand. In 1966 Kennett and his wife moved to the United States, as a pioneer of a new field of research, paleoceanography, a word he coined for the study of ancient oceans. Kennett was excited over the new research coming from sediment cores that were being drilled offshore. These rock cores contained detail records of tiny fossil foraminifera spanning millions of years, which unlocked the ancient record of the ocean at each location.

In the 1970s, Kennett began working with Sir Nicholas Shackleton, the great-nephew of the Antarctic Explorer Ernest Shackleton. Both were focused on a better understanding of the development of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and how it had resulted in the freezing of the Antarctic Continent, over the last 40 million years. Like Kennett, Shackleton also studied ocean floor sediments, measuring oxygen isotopes of the tiny foraminifera to infer ancient ocean floor temperatures from the past, using a scientific method developed by Harold Urey in the 1940s. Getting samples drilled off the shore of Antarctica was a challenge affair, but unlike the individual rock sampled collected while traveling around New Zealand on motorcycle, a drilled core reveals a more complete record of the sediments laid down over millions of years on the ocean floor. In the 1980s, both men became involved in the JOIDES Resolution drilling program, funded by the United States National Science Foundation, which also funds Antarctic exploration for the United States Government. The drilling program successfully drilled through millions of years of worth of sediment on the ocean floor, retrieving cores that would unlock a 90-million-year long history of ocean floor sedimentation off the coast of Antarctica.

The team was driven as much in seeking to understand the record of the more recent glaciation of Antarctica, as they were in finding the deep layer in the ocean core, that represented the moment when large dinosaurs became extinct. As an expert in foraminifera, Kennett and his colleague Lowell Stott, discovered a point in the recovered sediment core, where the foraminifera underwent a dramatic change. The large healthy foraminifera suddenly disappear in the core, replaced by a reddish mud, nearly absent of foraminifera. This layer also did not correspond with the extinction event that killed off the dinosaurs, but millions of years later at the end of the Paleocene Epoch. Isotopes of oxygen from the sedimented indicated that the ocean floor became very warm at this point in time. Kennett and Stott wrote a quick paper describing this catastrophic warming of the deep ocean waters around 56 million years ago near Antarctica in 1991, but soon other scientists observed the same features in rocks and core from around the world. In Luxor Egypt, from the same limestone rocks that were used to build the pyramids, geologists observed the same extinction event in rocks dated to 56 million years old and in Northern Wyoming geologists described a global warming event recorded in the Bighorn Basin of the same time effecting the mammals and plants. Something happened 56 million years to dramatically warm the deep ocean waters. The event was named the PETM (Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum). In the 30 years since the publication by Kennett and Stott, oceanographers have come to the dramatic realization that there can be periods of time when there is catastrophic mixing of deep and surface ocean waters.

The theory goes like this; 56 million years ago, the Arctic Ocean was only narrowly connected to the North Atlantic. The climate was much warmer today, so warm that the Arctic Ocean remained ice free throughout the year, despite the winter months being dark with the short days due to the high latitude at the North Pole. Rivers would drain into the Arctic Ocean during the spring, bringing freshwater. Since the climate was relatively cold, given its geography, evaporation was minimal. The yearly cycle of freshwater would stack on the colder saltier water each year, resulting in a highly stratified body of water. An example of this type of highly stratified body of water today is the Black Sea, but this was on a much larger scale. Each year the North Pole would pass through long summer days, with plenty of sunlight for photosynthesizing phytoplankton, then very short winter days, with little to no sunlight. Each year these blooms of algae and other photosynthesizing organisms would accumulate on the stratified deep ocean seafloor in the Arctic Ocean. Scavenging bacteria would convert this organic matter into methane, which would be trapped on the cold sea floor. This was a ticking bomb.

Around 56 million years ago, a massive set of underwater volcanic eruptions exploded on the ocean floor around present day Iceland and north into the Arctic Ocean. Warming deep ocean water caused these waters to rise, as warm water is less dense. Methane also undergoes sublimation at warmer temperatures. Sublimations is the transition of a substance directly from a solid to a gas phase. This methane gas bubbled up from the deep ocean floor of the Arctic Ocean, releasing massive amounts of methane into the atmosphere, a strong greenhouse gas. Very quickly the atmosphere became enriched in carbon dioxide as the methane reacted to the oxygen in the atmosphere. Suddenly the global climate became hotter and hotter, and the oceans warmed further. This run-away global warming event began to turn the global ocean acidic, killing off most of the tiny carbonate-shelled animals Kennett has spent his life studying. Such inversions of the ocean, where the deep ocean waters rise up to the surface, appears to have resulted in widespread anoxia (dead zones), methane release, and major extinctions of marine life due to acidic ocean waters. Such deep-water inversion events can be a consequence of run-away global warming, and the destabilization of the vast amounts of solid methane stored on the ocean floor, and often triggered by massive volcanic events. The heating of deep ocean water, results in the water rising to the surface, which can profoundly affect Earth over short spans of time. The current thermohaline circulation of the World’s Ocean keeps this from happening today (by moving surface ocean water downward in the North Atlantic), but many oceanographers worry about recent anthropogenic global warming, which could result in another inversion of the ocean, with deep ocean water rising to the surface. Comparable to the short horror story, The Call of Cthulhu by Lovecraft, the deep ocean is a frightful mysterious place, that in a sense, could destroy the world if it so wished.