Event Handling

| Navigate User Interface topic: |

The Java platform Event Model is the basis for event-driven programming on the Java platform.

Event-driven programming

[edit | edit source]No matter what the programming language or paradigm you are using, chances are that you will eventually run into a situation where your program will have to wait for an external event to happen. Perhaps your program must wait for some user input, or perhaps it must wait for data to be delivered over the network. Or perhaps something else. In any case, the program must wait for something to happen that is beyond the program's control: the program cannot make that event happen.

In this situation there are two general options for making a program wait for an external event to happen. The first of these is called polling and means you write a little loop of the for "while the event has not happened, check again". Polling is very simple to build and very straightforward. But it is also very wasteful: it means a program takes up processor time in order to do absolutely nothing but wait. This is usually considered too much of a drawback for programs that have to do a lot of waiting. Programs that have a lot of waiting moments (for example, programs that have a graphical user interface and often have to wait for long periods of time until the user does something) usually fare much better when they use the other mechanism: event-driven programming.

In event-driven programming a program that must wait, simply goes to sleep. It no longer takes up processor time, might even be unloaded from memory and generally leaves the computer available to do useful things. But the program doesn't completely go away; instead, it makes a deal with the computer or the operating system. A deal sort of like this:

Okay Mr. Operating System, since I have to wait for an event to happen, I'll go away and let you do useful work in the meantime. But in return, you have to let me know when my event has happened and let me come back to deal with it.

Event-driven programming usually has a pretty large impact on the design of a program. Usually, a program has to be broken up into separate pieces to do event-driven programming (one piece for general processing and one or more others to deal with events that occur). Event-driven programming in Java is more complicated than non-event driven but it makes far more efficient use of the hardware and sometimes (like when developing a graphical user interface) dividing your code up into event-driven blocks actually fits very naturally with your program's structure.

In this module we examine the basis of the Java Platform's facilities for event-driven programming and we look at some typical examples of how that basis has been used throughout the platform.

The Java Platform Event Model

[edit | edit source]Introduction

[edit | edit source]One of the most interesting things about support for event-driven programming on the Java platform is that there is none, as such. Or, depending on your point of view, there are many different individual pieces of the platform that offer their own support for event-driven programming.

The reason that the Java platform doesn't offer one general implementation of event-driven programming is linked to the origins of the support that the platform does offer. Back in 1996 the Java programming language was just getting started in the world and was still trying to gain a foothold and conquer a place for itself in software development. Part of this early development concentrated on software development tooling like IDEs. One of the trends in software development around that time was for reusable software components geared towards user interfaces: components that would encapsulate some sort of interesting, reusable functionality into a single package that could be handled as a single entity rather than as a loose collection of individual classes. Sun Microsystems tried to get on the component bandwagon by introducing what they called a JavaBean, a software component not only geared towards the UI but that could also be configured easily from an IDE. In order to make this happen Sun came up with a large specification of JavaBeans (the JavaBeans Spec) dealing mostly with naming conventions (to make the components easy to handle from an IDE). But Sun also realized at the same time that a UI-centric component would need support for an event-driven way of connecting events in the component to business logic that would have to be written by the individual developer. So the JavaBeans Spec also included a small specification for an event Model for the Java platform.

When they started working on this Event Model, the Sun engineers were faced with a choice: try to come up with a huge specification to encompass all possible uses of an event model, or just specify an abstract, generic framework that could be expanded for individual use in specific situations. They chose the latter option and so, love it or hate it, the Java Platform has no generic support for event-driven programming other than this general Event Model framework.

The Event Model framework

[edit | edit source]

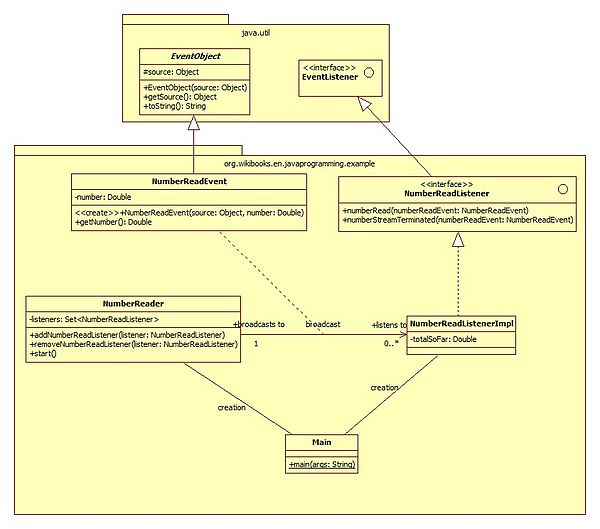

The Event Model framework is really very simple in and of itself, consisting of three classes (one abstract) and an interface. Most of all it consists of naming conventions that the programmer must obey. The framework is depicted in the image on the right.

Speaking in terms of classes and interfaces, the most important parts of the framework are the java.util.EventObject abstract class and the java.util.EventListener interface. These two types are the centerpieces of the rules and conventions of the Java Platform Event Model, which are:

- A class that has to be notified when an event occurs, is called an event listener. An event listener has one distinct method for each type of event notification that it is interested in.

- Event notification method declarations are grouped together into categories. Each category is represented by an event listener interface, which must extend

java.util.EventListener. By convention an event listener interface is named <Event category name>Listener. Any class that will be notified of events must implement at least one listener interface. - Any and all state related to an event occurrence will be captured in a state object. The class of this object must be a subclass of

java.util.EventObjectand must record at least which object was the source of the event. Such a class is called an event class and by convention is named <Event category name>Event. - Usually (but not necessarily!) an event listener interface will relate to a single event class. An event listener may have multiple event notification methods that take the same event class as an argument.

- An event notification method usually (but not necessarily!) has the conventional signature public void <specific event>(<Event category name>Event evt).

- A class that is the source of events must have a method that allows for the registration of listeners, one for each possible listener interface type. These methods must by convention have the signature public void add<Event category name>Listener(<Event category name>Listener listener).

- A class that is the source of events may have a method that allows for the deregistration of listeners, one for each possible listener interface type. These methods must by convention have the signature public void remove<Event category name>Listener(<Event category name>Listener listener).

That seems like a lot, but it's pretty simple once you get used to it. Take a look at the image on the left, which contains a general example of how you might use the framework. In this example we have a class called EventSourceClass that publishes interesting events. Following the rules of the Event Model, the events are represented by the InterestingEvent class which has a reference back to the EventSourceClass object (source, inherited from java.util.EventObject).

Whenever an interesting event occurs, the EventSourceClass must notify all of the listeners for that event that it knows about by calling the notification method that exist for that purpose. All of the notification methods (in this example there is only one, interestingEventOccurred) have been grouped together by topic in a listener interface: InterestingEventListener, which implements java.util.EventListener and is named according to the Event Model conventions. This interface must be implemented by all event listener classes (in this case only InterestingEventListenerImpl). Because EventSourceClass must be able to notify any interested listeners, it must be possible to register them. For this purpose the EventSourceClass has an addInterestingEventListener method. And since it is required, there is a removeInterestingEventListener method as well.

As you can clearly see from the example, using the Event Model is mostly about following naming conventions. This might seem a little cumbersome at first, but the point of having naming conventions is to allow automated tooling to access and use the event model. And there are indeed many tools, IDEs and frameworks that are based on these naming conventions.

Degrees of freedom in the Model

[edit | edit source]There's one more thing to notice about the Event Model and that is what is not in the Model. The Event Model is designed to allow implementations a large degree of freedom in the implementation choices made, which means that the Event Model can serve as the basis for a very wide range of specific, purpose-built event handling systems.

Aside from naming conventions and some base classes and interfaces, the Event Model specifies the following:

- It must be possible to register and deregister listeners.

- An event source must publish events by calling the correct notification method on all registered listeners.

- A call to an event notification method is a normal, synchronous Java call and the method must be executed by the same thread that called it.

But the Event Model doesn't specify how any of this must be done. There are no rules regarding which classes exactly must be event sources, nor about how they must keep track of registered event listeners. So one class might publish its own events, or be responsible for publishing the events that relate to an entire collection of objects (like an entire component). And an event source might allow listeners to be deregistered at any time (even in the middle of handling an event) or might limit this to certain times (which is relevant to multithreading).

Also, the Event Model doesn't specify how it must be embedded within any program. So, while the model specifies that a call to an event handling method is a synchronous call, the Model does not prescribe that the event handling method cannot hand off tasks to another thread or that the entire event model implementation must run in the main thread of the application. In fact, the Java Platform's standard user interface framework (Swing) includes an event handling implementation that runs as a complete subsystem of a desktop application, in its own thread.

Event notification methods, unicast event handling and event adaptors

[edit | edit source]In the previous section we mentioned that an event notification method usually takes a single argument. This is the preferred convention, but the specification does allow for exceptions to this rule if the application really needs that exception. A typical case for an exception is when the event notification must be sent across the network to a remote system though non-Java means, like the CORBA standard. In this case it is required to have multiple arguments and the Event Model allows for that. However, as a general rule the correct format for a notification method is

Code section 1.1: Simple notification method

public void specificEventDescription(Event_type evt)

|

Another thing we mentioned earlier is that, as a general rule, the Event Model allows many event listeners to register with a single event source for the same event. In this case the event source must broadcast any relevant events to all the registered listeners. However, once again the Event Model specification allows for an exception to the rule. If it is necessary from a design point of view you may limit an event source to registering a single listener; this is called unicast event listener registration. When unicast registration is used, the registration method must be declared to throw the java.util.TooManyListenersException exception if too many listeners are registered:

Code section 1.2: Listener registration

public void add<Event_type>Listener(<Event_type>Listener listener) throws java.util.TooManyListenersException

|

Finally, the specification allows for one more extension: the event adaptor. An event adaptor is an implementation of an event listener interface that can be inserted between an event source and an actual event listener class. This is done by registering the adaptor with the event source object using the regular registration method. Adaptors are used to add additional functionality to the event handling mechanism, such as routing of event objects, event filtering or enriching of the event object before processing by an actual event handler class.

A simple example

[edit | edit source]In the previous section we've explored the depths (such as there are) of the Java platform Event Model framework. If you're like most people, you've found the theoretical text more confusing than the actual use of the model. Certainly more confusing than should be necessary to explain what is, really, quite a simple framework.

In order to clear everything up a bit, let's examine a simple example based on the Event Model framework. Let's assume that we want to write a program that reads a stream of numbers input by the user at the command line and processes this stream somehow. Say, by keeping track of the running sum of numbers and producing that sum once the stream has been completely read.

Of course we could implement this program quite simply with a loop in a main() method. But instead let's be a little more creative. Let's say that we want to divide our program neatly into classes, each with a responsibility of its own (like we should in a proper, object-oriented design). And let's imagine that we want it to be possible not only to calculate the sum of all the numbers read, but to perform any number of calculations on the same number stream. In fact, it should be possible to add new calculations with relative ease and without having to affect any previously existing code.

If we analyze these requirements, we come to the conclusion that we have a number of different responsibilities in the program:

Using the Event Model framework allows us to separate the two main responsibilities cleanly and affords us the flexibility we are looking for. If we implement the logic for reading the number stream in a single class and treat the reading of a single number as an event, the Event Model allows us to broadcast that event (and the number) to as many stream processors as we like. The class for reading the number stream will act as the event source of the program and each stream processor will be a listener. Since each listener is a class of its own and can be registered with the stream reader (or not) this means our model allows us to have multiple, independent stream processing that we can add on to without affecting the code to read the stream or any pre-existing stream processor.

The Event Model says that any state associated with an event should be included in a class that represents the event. That's perfect for us; we can implement a simple event class that will record the number read from the command line. Each listener can then process this number as it sees fit.

For our interesting event set let's keep things simple: let's limit ourselves to having read a new number and having reached the end of the stream. With this choice we come to the following design for our example application:

In the following sections we look at the implementation of this example.

Example basics

[edit | edit source]Let's start with the basics. According to the Event Model rules, we must define an event class to encapsulate our interesting event. We should call this class something-somethingEvent. Let's go for NumberReadEvent, since that's what will interest us. According to the Model rules, this class should encapsulate any state that belongs with an event occurrence. In our case, that's the number read from the stream. And our event class must inherit from java.util.EventObject. So all in all, the following class is all we need:

Code listing 1.1: NumberReadEvent.

package org.wikibooks.en.javaprogramming.example;

import java.util.EventObject;

public class NumberReadEvent extends EventObject {

private double number;

public NumberReadEvent(Object source, Double number) {

super(source);

this.number = number;

}

public double getNumber() {

return number;

}

}

|

Next, we must define a listener interface. This interface must define methods for interesting events and must extend java.util.EventListener. We said earlier our interesting events were "number read" and "end of stream reached", so here we go:

Code listing 1.2: NumberReadListener.

package org.wikibooks.en.javaprogramming.example;

import java.util.EventListener;

public interface NumberReadListener extends EventListener {

public void numberRead(NumberReadEvent numberReadEvent);

public void numberStreamTerminated(NumberReadEvent numberReadEvent);

}

|

Actually the numberStreamTerminated method is a little weird, since it isn't actually a "number read" event. In a real program you'd probably want to do this differently. But let's keep things simple in this example.

The event listener implementation

[edit | edit source]So, with our listener interface defined, we need one or more implementations (actual listener classes). At the very least we need one that will keep a running sum of the numbers read. We can add as many as we like, of course. But let's stick with just one for now. Obviously, this class must implement our NumberReadListener interface. Keeping a running summation is a matter of adding numbers to a field as the events arrive. And we wanted to report on the sum when the end of the stream is reached; since we know when that happens (i.e. the numberStreamTerminated method is called), a simple println statement will do:

Code listing 1.3: NumberReadListenerImpl.

package org.wikibooks.en.javaprogramming.example;

public class NumberReadListenerImpl implements NumberReadListener {

double totalSoFar = 0D;

@Override

public void numberRead(NumberReadEvent numberReadEvent) {

totalSoFar += numberReadEvent.getNumber();

}

@Override

public void numberStreamTerminated(NumberReadEvent numberReadEvent) {

System.out.println("Sum of the number stream: " + totalSoFar);

}

}

|

So, is this code any good? No. It's yucky and terrible and most of all not thread safe. But it will do for our example.

The event source

[edit | edit source]This is where things get interesting: the event source class. This is the interesting place because this is where we must put code to read the number stream, code to send events to all the listeners and code to manage listeners (add and remove them and keep track of them).

Let's start by thinking about keeping track of listeners. Normally this is a tricky business, since you have to take all sorts of multithreading concerns into account. But we're being simple in this example, so let's just stick with a simple java.util.Set of listeners. Which we can initialize in the constructor:

Code section 1.1: The constructor

private Set<NumberReadListener> listeners;

public NumberReader() {

listeners = new HashSet<NumberReadListener>();

}

|

That choice makes it really easy to implement adding and removing of listeners:

Code section 1.2: The register/deregister

public void addNumberReadListener(NumberReadListener listener) {

this.listeners.add(listener);

}

public void removeNumberReadListener(NumberReadListener listener) {

this.listeners.remove(listener);

}

|

We won't actually use the remove method in this example — but recall that the Model says it must be present.

Another advantage of this simple choice is that notification of all the listeners is easy as well. We can just assume any listeners will be in the set and iterate over them. And since the notification methods are synchronous (rule of the model) we can just call them directly:

Code section 1.3: The notifiers

private void notifyListenersOfEndOfStream() {

for (NumberReadListener numberReadListener : listeners) {

numberReadListener.numberStreamTerminated(new NumberReadEvent(this, 0D));

}

}

private void notifyListeners(Double d) {

for (NumberReadListener numberReadListener: listeners) {

numberReadListener.numberRead(new NumberReadEvent(this, d));

}

}

|

Note that we've made some assumptions here. For starters, we've assumed that we'll get the Double value d from somewhere. Also, we've assumed that no listener will ever care about the number value in the end-of-stream notification and have passed in the fixed value 0 for that event.

Finally we must deal with reading the number stream. We'll use the Console class for that and just keep on reading numbers until there are no more:

Code section 1.4: The main method

public void start() {

Console console = System.console();

if (console != null) {

Double d = null;

do {

String readLine = console.readLine("Enter a number: ", (Object[])null);

d = getDoubleValue(readLine);

if (d != null) {

notifyListeners(d);

}

} while (d != null);

notifyListenersOfEndOfStream();

}

}

|

Note how we've hooked the number-reading loop into the event handling mechanism by calling the notify methods? The entire class looks like this:

Code listing 1.4: NumberReader.

package org.wikibooks.en.javaprogramming.example;

import java.io.Console;

import java.util.HashSet;

import java.util.Set;

public class NumberReader {

private Set<NumberReadListener> listeners;

public NumberReader() {

listeners = new HashSet<NumberReadListener>();

}

public void addNumberReadListener(NumberReadListener listener) {

this.listeners.add(listener);

}

public void removeNumberReadListener(NumberReadListener listener) {

this.listeners.remove(listener);

}

public void start() {

Console console = System.console();

if (console != null) {

Double d = null;

do {

String readLine = console.readLine("Enter a number: ", (Object[])null);

d = getDoubleValue(readLine);

if (d != null) {

notifyListeners(d);

}

} while (d != null);

notifyListenersOfEndOfStream();

}

}

private void notifyListenersOfEndOfStream() {

for (NumberReadListener numberReadListener: listeners) {

numberReadListener.numberStreamTerminated(new NumberReadEvent(this, 0D));

}

}

private void notifyListeners(Double d) {

for (NumberReadListener numberReadListener: listeners) {

numberReadListener.numberRead(new NumberReadEvent(this, d));

}

}

private Double getDoubleValue(String readLine) {

Double result;

try {

result = Double.valueOf(readLine);

} catch (Exception e) {

result = null;

}

return result;

}

}

|

Running the example

[edit | edit source]Finally, we need one more class: the kickoff point for the application. This class will contain a main() method, plus code to create a NumberReader, a listener and to combine the two:

Code listing 1.5: Main.

package org.wikibooks.en.javaprogramming.example;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

NumberReader reader = new NumberReader();

NumberReadListener listener = new NumberReadListenerImpl();

reader.addNumberReadListener(listener);

reader.start();

}

}

|

If you compile and run the program, the result looks somewhat like this:

An example run

>java org.wikibooks.en.javaprogramming.example.Main Enter a number: 0.1 Enter a number: 0.2 Enter a number: 0.3 Enter a number: 0.4 Enter a number: |

Output

Sum of the number stream: 1.0 |

Extending the example with an adaptor

[edit | edit source]Next, let's take a look at applying an adaptor to our design. Adaptors are used to add functionality to the event handling process that:

- is general to the process and not specific to any one listener; or

- is not supposed to affect the implementation of specific listeners.

According to the Event Model specification a typical use case for an adaptor is to add routing logic for events. But you can also add filtering or logging. In our case, let's do that: add logging of the numbers as "proof" for the calculations done in the listeners.

An adaptor, as explained earlier, is a class that sits between the event source and the listeners. From the point of view of the event source, it masquerades as a listener (so it must implement the listener interface). From the point of view of the listeners it pretends to be the event source (so it should have add and remove methods). In other words, to write an adaptor you have to repeat some code from the event source (to manage listeners) and you have to re-implement the event notification methods to do some extra stuff and then pass the event on to the actual listeners.

In our case we need an adaptor that writes the numbers to a log file. Keeping it simple once again, let's settle for an adaptor that:

- Uses a fixed log file name and overwrites that log file with every program run.

- Opens a

FileWriterin the constructor and just keeps it open. - Implements the

numberReadmethod by writing the number to theFileWriter. - Implements the

numberStreamTerminatedmethod by closing theFileWriter.

Also, we can make life easy on ourselves by just copying all the code we need to manage listeners over from the NumberReader class. Again, in a real program you'd want to do this differently. Note that each notification method implementation also passes the event on to all the real listeners:

Code listing 1.6: NumberReaderLoggingAdaptor.

package org.wikibooks.en.javaprogramming.example;

import java.io.BufferedWriter;

import java.io.FileWriter;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.util.HashSet;

import java.util.Set;

public class NumberReaderLoggingAdaptor implements NumberReadListener {

private Set<NumberReadListener> listeners;

private BufferedWriter output;

public NumberReaderLoggingAdaptor() {

listeners = new HashSet<NumberReadListener>();

try {

output = new BufferedWriter(new FileWriter("numberLog.log"));

} catch (IOException e) {

// TODO Auto-generated catch block

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

public void addNumberReadListener(NumberReadListener listener) {

this.listeners.add(listener);

}

public void removeNumberReadListener(NumberReadListener listener) {

this.listeners.remove(listener);

}

@Override

public void numberRead(NumberReadEvent numberReadEvent) {

try {

output.write(numberReadEvent.getNumber() + "\n");

} catch (Exception e) {

}

for (NumberReadListener numberReadListener: listeners) {

numberReadListener.numberRead(numberReadEvent);

}

}

@Override

public void numberStreamTerminated(NumberReadEvent numberReadEvent) {

try {

output.flush();

output.close();

} catch (Exception e) {

}

for (NumberReadListener numberReadListener: listeners) {

numberReadListener.numberStreamTerminated(numberReadEvent);

}

}

}

|

Of course, to make the adaptor work we have to make some changes to the bootstrap code:

Code listing 1.7: Main.

package org.wikibooks.en.javaprogramming.example;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

NumberReader reader = new NumberReader();

NumberReadListener listener = new NumberReadListenerImpl();

NumberReaderLoggingAdaptor adaptor = new NumberReaderLoggingAdaptor();

adaptor.addNumberReadListener(listener);

reader.addNumberReadListener(adaptor);

reader.start();

}

}

|

But note how nicely and easily we can re-link the objects in our system. The fact that adaptors and listeners both implement the listener interface and the adaptor and event source both look like event sources means that we can hook the adaptor into the system without having to change a single statement in the classes that we developed earlier.

And of course, if we run the same example as given above, the numbers are now recorded in a log file.

Platform uses of the Event Model

[edit | edit source]The Event Model, as mentioned earlier, doesn't have a single all-encompassing implementation within the Java platform. Instead, the model serves as a basis for several different purpose-specific implementations, both within the standard Java platform and outside it (in frameworks).

Within the platform the main implementations are found in two areas:

- As part of the JavaBeans classes, particularly in the support classes for the implementation of PropertyChangeListeners.

- As part of the Java standard UI frameworks, AWT and Swing.