Issues in Interdisciplinarity 2019-20/Power and Pregnancy

Introduction

[edit | edit source]As the source of human species renewal, pregnancy can be considered the ultimate source of power. However, while it is the female body that is the physical source of this power, a cross-disciplinary examination shows that often it is controlled by, and serves the interests of, individuals, groups, or ideas other than the woman herself.[1]

Power is generally seen as either ‘power over’[2] or ‘power to’,[3][4] with diversity within these categories. This chapter approaches the issue from 4 disciplinary perspectives, each with different conceptualisations of power both now and in their past.

Medical History

[edit | edit source]

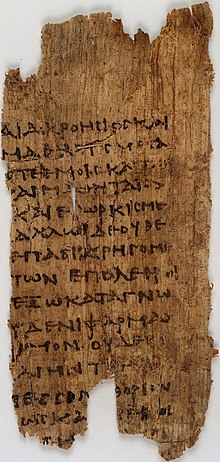

Physicians exist in a place of hypothetical power over life, as illustrated by the Hippocratic oath, whereby the cultural necessity to believe that physicians are benevolent is underpinned by the potential for harm. This tenuous contract between those who have knowledge and those reliant on it is inescapably reliant on a power imbalance. Pregnant women do not fit into this paradigm: as harbinger of life, they become active subjects, causing a backlash to realign the power dynamics. Doctors take up the role of ‘special bodies of public power’ and ‘institutions of coercion’[5] in ways bodies like the police cannot. Normally emphasis on the human relationship between the physician and patient curtails this, but when societal status quo is threatened, doctor-patient interpersonal relationships become oppressive, feeding into the discipline as a whole. For example James Marion Sims, the ‘father of modern gynecology’,[6] routinely experimented on pregnant black slaves without anaesthesia or any modern conception of consent. Female slaves’ lack of agency over their high pregnancy rate echoed their lack of cultural or political power as commodities creating more commodities. Sims was a ‘special body’ wielding power over his patients, as the dehumanisation of slaves made the Hippocratic Oath irrelevant. When Sims later operated - with anaesthesia - on white women his work was denounced as invasive, ‘reckless and lethal’, illustrating how the power of pregnancy is contextual. Sims’ techniques allowed the cure of vesico-vaginal fistula. A vaginal speculum and a rectal examination position are named after him.

Biological and Social Evolution

[edit | edit source]Biological

An understanding of power as physical ability can be applied to the physical and social evolution of human beings. From a medical perspective, the nine month gestation period puts women in a position of physical dependency. The obstetrical dilemma suggests childbirth is more difficult for humans than other species, due mainly to the size of the foetus’ head. Humans are an altricial species: the infant is born neurologically underdeveloped compared to similar species because the mother’s body would not be able to birth a child with a more developed brain. Human childbirth significantly diminishes the mother’s physical power. Furthermore, altricial species are born immobile and helpless, and must be cared for extensively by the mother. The Energetics of Gestation and Growth (EGG) hypothesis [7] contests the obstetrical dilemma by suggesting that women give birth when their body reaches the maximum metabolic rate for survival. While the reasons given are different, both theories claim that childbirth pushes the mother's physical power to absolute capacity.

Social

Studies have shown that historically women’s social status was dependent on how much they could provide for the community. Previously, in hunter-gatherer societies women’s gathering provided three times more calories than men’s hunting,[8] but the Neolithic Revolution lead to settlement and farming, to which male physical strength was more suited. Women were less able to contribute to the production economy, and turned to domestic work.

Settlement, a social phenomenon, may have influenced biological evolution by enabling a carbohydrate-rich diet that altered foetal anatomy to make them shorter and fatter,[9] thus further complicating pregnancy and cementing the male-female division of labour that remains prominent to this day. [10]

Sociology

[edit | edit source]Arnold Van Gennep described a rites of passage as an individual's journey from a group to another, characterised by the stages of separation, liminality and aggregation. For nine months, the expectant mother inhabits the vulnerable stage of liminality- belonging neither to her old life as a lone individual nor to her new life as a mother.

Sociologists Warren and Brewis researched the distress felt by pregnant women at the lack of jurisdiction over their changing body in the context of the Western obsession with body modification.[11] Calming personal gestures such as touching the pregnant belly can be an expression of a deeper anxiety about personal bodily autonomy, and serve to domesticate a foreign body. The normalisation of others touching the belly, usually a breach of acceptable social behaviour, shows that the baby is already separate from the mother, belonging more to society.[12]

Even before childbirth, the mother is expected to put the interests of the foetus above her own, a principle that extends into motherhood more broadly.

While there has long been a pressure for women to remain attractive throughout their lives, the obsession with getting back into shape postpartum is intense. The Romanisation[13] of pregnancy sells an image far divorced from the heavy physical realities. The sexualisation of pregnancy, such as in photoshoots by Demi Moore are equally glorifying. However, the performative aspect can be both distressing and empowering, considering that in the past women have been completely isolated and deprived of their sexual power.

Political Geography

[edit | edit source]Historically, pregnancy has been a demographic resource that has been controlled in order to increase a nation’s geographical, material and ideological power.[14][15] Foucault described such population control techniques as ‘biopower’.

Different economic systems have favoured various types of geopolitical power, while remaining heavily dependent on population

The Mercantilist focus on promoting domestic industry lead to major efforts to increase the working population to increase production and gain material power[16]. Writers like Jean Francois Melon[17] proposed population-control measures that were implemented throughout Europe. As well as maximising domestic production, nations used their colonies to provide essential goods, and ensured stability within these by encouraging the growth of the settler population;[18] for instance, shipping young brides across the Atlantic for male settlers. While the immediate gain was material power, settler colonialism ultimately brought geographic power, and permanently changed the ethnic and cultural landscape.

European Communist states sought material power, as success legitimised Communism to the Capitalist world. Most did not regulate fertility, with the exception of Romania and Bulgaria, which issued bans on abortion.[19] However, Romania did not seek autonomy from the West,[20] but from the Soviet Union, after its rejection of internationalism in 1964. The new generation was an experiment in the “political reconstruction of the family”.[21][22]

Within Western capitalism, it is the relational power between intergovernmental organisations that is increasingly sought-after. The post-industrial shift from the manufacturing sector to the service sector has meant that population growth no longer equals economic growth, marking a sharp decline in economically-driven population control.[23]

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Hannah Arendt[24] describes power as something that “springs up” between people and “vanishes when they disperse”. While the above disciplines have wildly different understandings of power, they are all inherently relational. At a fundamental level they concern the relationship between the pregnant mother and the rest of the world, be it be through her gynaecologist, her anatomy, her culture, her society, her identity, or her state.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ O'Brien M., The Politics of Reproduction, Unwin Hyman; 1983.

- ↑ T. Waters and D. Waters,Weber's Rationalism and Modern Society: New Translations on Politics, Bureaucracy, and Social Stratification, Chapter 7: Politics as vocation, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015

- ↑ Dowding K. Rational Choice and Political Power, Aldershot: Edward Elgar; 1991.

- ↑ Pitkin H. Wittgenstein and justice, Berkeley: University of California Press; 1993.

- ↑ Friedrich Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and State, 1884

- ↑ [1] Sara Spettel and Mark Donald White, The Portrayal of J. Marion Sims’ Controversial Surgical Legacy, Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Albany Medical College, Albany, New York

- ↑ [2] Dunswort, Warrener, Deacon, Ellison, and Pontzerd, Metabolic hypothesis for human altriciality, 2012

- ↑ [3] Torben Iversen and Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Explaining Occupational Gender Inequality: Hours Regulation and Statistical Discrimination, 2011, Seattle Washington

- ↑ [4] Barras,The real reasons why childbirth is so painful and dangerous, BBC, 2016

- ↑ [5] Casper Worm Hansen, Peter Sandholt Jensen, Christian Skovsgaard, Gender Roles and Agricultural History:The Neolithic Inheritance, 2015

- ↑ [6],S. Warren, J.Brewis, Matter over mind? Examining the experience of pregnancy, Sage Publications, 2004

- ↑ [7] Sally Raskoff,Pregnancy and social interactions, Everydaysociologyblog.com, 18 July 2013

- ↑ [8] Kelly Oliver, Knock Me Up, Knock Me Down, Columbia University Press, 2012

- ↑ Flint C, Introduction to geopolitics. 2nd ed, Abingdon: Routledge; 2011.

- ↑ Painter J, Jeffrey A. Political Geography. 1st ed., London: SAGE; 2009.

- ↑ Overbeek, J. (1973). Mercantilism, physiocracy and population theory. Honolulu: Population Institute, East-West Center

- ↑ Melon J.F. Essai politique sur le commerce, Paris, Guillaumin, 1736

- ↑ [9] Gordon N, Ram M, Ethnic cleansing and the formation of settler colonial geographies, 2016

- ↑ Gal S, Klingman G. The Politics of Gender after Socialism. 1st ed., Chichester: Princeton University Press; 2000.

- ↑ [10] M. Percival, M. Britain's ‘Political Romance’ with Romania in the 1970s,

- ↑ Kligman G. The politics of duplicity. 1st ed., University of California Press; 1998.

- ↑ Iepan F. Children of the Decree. Romania; 2004 (film)

- ↑ Gimenez M. Marx, Women and capitalist social reproduction, Brill

- ↑ Arendt H. The human condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1958.