Issues in Interdisciplinarity 2018-19/Truth and Art

Introduction

[edit | edit source]What deems art as ‘true’? What is ‘true art’? Truth in art can be examined in its capacity to imitate reality, its intention and reception, authenticity and subjective value. Defining ‘true art’ is associated with other disciplines in understanding its contextual information and the narrative behind it. Art can be understood as a model to envision the world from a personal point of view. Thus the question of ‘true art’ involves a subjective view of truth. Understanding art as models of the world can also help draw conclusions on other models, such as those of scientific nature, therefore acknowledging how 'truth in art' is an interdisciplinary concern.

Reality and Truth

[edit | edit source]

Possibly art is most truthful when depicting reality. The correspondence theory of truth elaborates: ‘truth or the falsity of a representation is determined solely by how it relates to a reality; that is, by whether it accurately describes that reality’ [2]. How can we represent reality? Does direct imitation still omit part of reality? When art attempts to imitate reality, is it through hyper-realism, or can we also accept an abstract representation? Arguably then, artworks such as Matisse’s The Snail and Mondrian’s New York City I represent a form of reality, by interpreting visual stimulus in unexpected ways. Different artistic styles have the capacity to impart distinctive truths; the artist communicates their truth and the viewer interprets it to determine which they find truer to their own reality. Hence, can art ever be ‘untrue’? If artists and viewers decipher artworks individually, then art is subjective and cannot be ‘untrue’.

Art is a strand of aesthetic truth, which can be used to reveal other forms of truth, such as historical truth. It can inform historical events by contributing the artist’s personal understanding of reality. The artist’s response enriches the objective historical truth by providing a subjective emotional reaction. An example is Otto Dix’s Der Krieg: his representation of WWI is used in history books[3] as a visual support to historical truth. As a frontline soldier, his depictions of war horror challenge society’s heroic view of war. Without emotional artistic depictions, understanding history can be one-dimensional. Together, art and history enable a more inclusive portrayal of truth, bringing us closer to the event’s true reality.

Authenticity

[edit | edit source]What is meant by ‘authentic’ art? The Tate Gallery describes authenticity as ‘a term used [...] to describe the qualities of an original work of art as opposed to a reproduction’ [4]. An example of this would be the comparison between Classical Roman and Greek sculpture. With the expansion of the Roman Empire, a multitude of Greek art was introduced and favoured by the Romans, leading to the distribution of these reproductions across the empire. Thus, are they ‘art’ or just forgeries of the original? There are several factors of truth in determining authenticity, such as time period and historical, social and political context. For this reason, the true nature of art is inextricably linked to its contextual information, deducing that its authenticity is ascertained by many other disciplines.

Consequently, what is the value of reproductions? Is truth in value based on skill or authenticity? Traditional artworks continue to be remoulded within conceptual art. Wolfe von Lenkiewicz references masterpieces and significant historical figures within his work, evoking the notion that artists are inescapably influenced by art of the past. His exhibition The School of Night comments on the idea of ownership and questions whether artwork can ever be truly ‘authentic’ [5]. Similarly, transcriptions of past artworks have the ability to suggest distinct ideas to those presented within the original. An example of this is Velazquez’s Las Meninas. Picasso alone made 58 transcriptions [6] in a variety of compositions, each remarking upon something different. Are these transcriptions 'authentic'? They have reproduced the subject matter and composition of a previous work, but have created something different and original. As suggested by von Lenkiewicz [5], isn’t all artwork variations of previous work, whether an intentional transcription or not?

Intention and Institutions

[edit | edit source]Questions also arise when considering the truth of intention. Who decides the art’s intention: the viewer, the institution or the artist? Marcel Duchamp’s theory of readymade expands upon this, determining ‘that what is art is defined by the artist' [4]. Therefore, it is important to consider who determines the nature and intention of the artwork. Do we suppose a piece is ‘art’ because it is displayed within a relevant institution? Is art valid or true just because an institution displays it? Institutions possess asymmetrical influence over the visitors, imposing a certain vision of 'true art’ through curation and narrative. The authority they acquire is supported by the public’s confidence in them, rooted in the sociological concept of ‘institutional trust’ [5]. This idea was interrogated when two students left a pair of glasses on the floor of a San Francisco gallery as a prank, only for it to be assumed by other visitors as displayed artwork [6]. This incites conversation around the definition of ‘art’ and its intention: would we accept, for example, a simple chair as ‘true art’ if it was displayed in an art gallery, questioning its purpose or significance? Accordingly, was the spurious installation of the glasses placed by the students ‘true art’? While they had not intended it to be so, by inspiring conversation and reflection, perhaps it became ‘true art’ in its own subjective right.

Scientific and Artistic Models

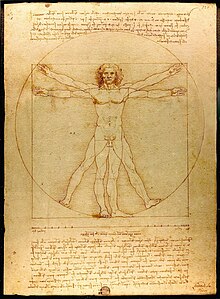

[edit | edit source]This discussion is relevant to understanding and developing scientific models. Both scientific and artistic models build on previous ideas and celebrate originality over reproductions. Both models are a representation of reality, providing a clearer understanding of complex ideas. However, science can be proven ‘untrue’, so are artistic models a more truthful representation of reality? The two models are distinct, as artistic models are subjective, whilst scientific ones are more objective, and their validity can be proven by evidence. This often means scientific models are valued more highly. Who determines their value? Just as artistic institutions have the authority to install hierarchy between artworks, scientific institutions determine and authorise the value of scientific models. By combining the models, we can achieve a wider understanding of our surroundings, as they each reveal truths that the other model omits. Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Vitruvian Man exemplifies this, as he drew on knowledge from both disciplines to depict what he intended to be the reality of the human form [8]. This demonstrates that applying both models and looking at their interconnections provides a more expansive perspective and thus a more truthful depiction of the subject, than studying the disciplines separately.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Conclusively, ‘true art’ is determined by its intention, authenticity and likeness to reality. Why do we need art to be true? Art as a model of the world thus claims itself to be truthful, as we then use this model to discover additional truths. This is comparable to scientific models, as they share this purpose. By taking both models into consideration, we are more likely to engage with all facets of truth, gaining a more coherent understanding of a concept. Art will always be interdisciplinary because it continually draws from other disciplines as primary inspiration and reciprocally informs these disciplines as a way of thinking.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Wikidata contributors.Q1871066. Wikidata. 19 November 2018. Available from: https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?title=Q18710663&oldid=793441845 [Accessed 7 December 2018]

- ↑ David M. The Correspondence Theory of Truth. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 10 May 2002. Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/truth-correspondence/ [Accessed 24 November 2018]

- ↑ Ivernel M., Villemagne B. Histoire-Géographie 3e. p20. Hatier Parution. 2016.

- ↑ The Tate Gallery. Authenticity – Art Term. The Tate Gallery. Available from: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/r/readymade [Accessed 1 December 2018]

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. Institutional trust (social sciences). Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Available from: w:Special:PermanentLink/815960113 [Accessed 7 December 2018]

- ↑ Mele C. Is It Art? Eyeglasses on Museum Floor Began as Teenagers’ Prank. 30 May 2016. The New York Times. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/31/arts/sfmoma-glasses-prank.html [Accessed 29 November 2018]

- ↑ Wikidata contributors.Q21548. Wikidata. 20 November 2018. Available from: https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?title=Q215486&oldid=794550374 [Accessed 7 December 2018]

- ↑ Zöllner F. Leonardo. Cologne: Taschen. 2015.