Introduction to Paleoanthropology/Print version

| This is the print version of Introduction_to_Paleoanthropology You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

Note: current version of this book can be found at http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Introduction_to_Paleoanthropology Remember to click "refresh" to view this version.

Table of contents

- Defining Paleoanthropology

- Origin of Paleoanthropology

- Importance of Bones

- Early Hominid Fossils

- Phylogeny and Chronology

- Early Hominid Behavior

- Oldowan

- Acheulean

- Hominids of the Acheulean

- Technology in the Acheulean

- Hominids of the Middle Paleolithic

- Technology of the Middle Paleolithic

- Upper Paleolithic

- Dating Techniques

- Cultural Evolution

- Darwinian Thought

- Genetics

- Contemporary Primates

- Humans as Primates

- Origin of Language

From Hunter-Gatherer to Food Producer Variation in Modern Human Populations

Definition

To effectively study paleoanthropology, one must understand that it is a subdiscipline of anthropology and have a basic understanding of archaeology dating techniques, evolution of cultures, Darwinian thought, genetics, and primate behaviours.

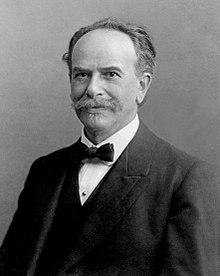

There is a long academic tradition in modern anthropology which is divided into four fields, as defined by Franz Boas (1858-1942), who is generally considered the father of the Anthropology in the United States of America. The study of anthropology falls into four main fields:

- Sociocultural anthropology

- Linguistic anthropology

- Archaeology

- Physical anthropology

Although these disciplines are separate, they share common goals. All forms of anthropology focus on the following:

- Diversity of human cultures observed in past and present.

- Human beings in all of their biological, social, and cultural complexity.

- Many other disciplines in the social sciences, natural sciences, and even humanities are involved in study of human cultures.

- Examples include: Psychology, geography, sociology, political science, economics, biology, genetics, history and even art and literature.

Sociocultural anthropology/ethnology

This field can trace its roots to processes of European colonization and globalization, when European trade with other parts of the world and eventual political control of overseas territories offered scholars access to different cultures. Anthropology was the scientific discipline that searches to understand human diversity, both culturally and biologically. Originally anthropology focused on understanding groups of people then considered "primitive" or "simple" whereas sociology focused on modern urban societies in Europe and North America although more recently cultural anthropology looks at all cultures around the world, including those in developed countries. Over the years, sociocultural anthropology has influenced other disciplines like urban studies, gender studies, ethnic studies and has developed a number of sub-disciplines like medical anthropology, political anthropology, environmental anthropology, applied anthropology, psychological anthropology, economic anthropology and others have developed.

Linguistic anthropology

This study of human speech and languages includes their structure, origins and diversity. It focuses on comparison between contemporary languages, identification of language families and past relationships between human groups. It looks at:

- Relationship between language and culture

- Use of language in perception of various cultural and natural phenomena

- Process of language acquisition, a phenomenon that is uniquely human, as well as the cognitive, cultural, and biological aspects involved in the process.

- Through historical linguistics we can trace the migration trails of large groups of people (be it initiated by choice, by natural disasters, by social and political pressures). In reverse, we can trace movement and establish the impact of the political, social and physical pressures, by looking at where and when the changes in linguistic usage occurred.

Archaeology

Is the study of past cultures through an analysis of artifacts, or materials left behind gathered through excavation. This is in contrast to history, which studies past cultures though an analysis of written records left behind. Archaeology can thus examine the past of cultures or social classes that had no written history. Historical archaeology can be informed by historical information although the different methods of gathering information mean that historians and archaeologists are often asking and answering very different kinds of questions. It should be noted that recovery and analysis of material remains is only one window to view the reconstruction of past human societies, including their economic systems, religious beliefs, and social and political organization. Archaeological studies are based on:

- A specific methodology to recover material remains including excavation techniques, stratigraphy, chronology, and dating techniques

- Animal bones, plant remains, human bones, stone tools, pottery, structures (architecture, pits, hearths).

Physical anthropology

Is the study of human biological variation within the framework of evolution, with a strong emphasis on the interaction between biology and culture. Physical anthropology has several subfields:

- Paleoanthropology

- Osteometry/osteology

- Forensic anthropology

- Primatology

- Biological variation in living human populations

- Bioarchaeology/paleopathology

Paleoanthropology

As a subdiscipline of physical anthropology that focuses on the fossil record of humans and non-human primates. This field relies on the following:

- Understanding Human Evolution

Evolution of hominids from other primates starting around 8 million to 6 million years ago. This information is gained from fossil record of primates, genetics analysis of humans and other surviving primate species, and the history of changing climate and environments in which these species evolved.

- Importance of physical anthropology

Evidence of hominid activity between 8 and 2.5 million years ago usually only consists of bone remains available for study. Because of this very incomplete picture of the time period from the fossil record, various aspects of physical anthropology (osteometry, functional anatomy, evolutionary framework) are essential to explain evolution during these first millions of years. Evolution during this time is considered as the result of natural forces only.

- Importance of related disciplines

Paleoanthropologists need to be well-versed in other scientific disciplines and methods, including ecology, biology, anatomy, genetics, and primatology. Through several million years of evolution, humans eventually became a unique species. This process is similar to the evolution of other animals that are adapted to specific environments or "ecological niches". Animals adapted to niches usually play a specialized part in their ecosystem and rely on a specialized diet.

Humans are different in many ways from other animals. Since 2.5 million years ago, several breakthroughs have occurred in human evolution, including dietary habits, technological aptitude, and economic revolutions. Humans also showed signs of early migration to new ecological niches and developed new subsistence activities based on new stone tool technologies and the use of fire. Because of this, the concept of an ecological niche does not always apply to humans any more.

Summary

The following topics were covered:

- Introduced field of physical anthropology;

- Physical anthropology: study of human biology, non-human primates, and hominid fossil record;

- Placed paleoanthropology within overall context of anthropological studies (along with cultural anthropology, linguistics, and archaeology);

Further modules in this series will focus on physical anthropology and be oriented toward understanding of the natural and cultural factors involved in the evolution of the first hominids.

Beginning of the 20th Century

In 1891, Eugene Dubois discovers remains of hominid fossils (which he will call Pithecanthropus) on the island of Java, in southeast Asia. The two main consequences of this discovery:

- stimulated research for a "missing link" in our origins

- oriented research interest toward southeast Asia as possible cradle of humanity

Yet, in South Africa, 1924, Raymond Dart accidentally discovered the remains of child (at Taung) during exploitation of a quarry and publishes them in 1925 as a new species - Australopithecus africanus (which means "African southern ape"). Dart, a British-trained anatomist, was appointed in 1922 professor of anatomy at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Through this discovery, Dart:

- documented the ancient age of hominids in Africa and

- questioned the SE Asian origin of hominids, arguing for a possible African origin.

Nevertheless, Raymond Dart's ideas were not accepted by the scientific community at the time because:

- major discoveries carried out in Europe (such as Gibraltar, and the Neander Valley in Germany) and Asia (Java) and

- remains of this species were the only ones found and did not seem to fit in phylogenetic tree of our origins and

- ultimately considered simply as a fossil ape.

It took almost 20 years before Dart's ideas could be accepted, due to notable new discoveries:

- in 1938, identification of a second species of Australopithecine, also in South Africa: Paranthropus (Australopithecus) robustus. Robert Broom collected at Kromdraai Cave the remains of a skull and teeth,

- in 1947, other remains of Australopithecus africanus found at Sterkfontein and Makapansgat, and

- in 1948, other remains of Paranthropus robustus found at Swartkrans, also by R. Broom.

1950s - 1970s

During the first half of the 20th century, most discoveries essential for paleoanthropology and human evolution were done in South Africa.

After World War II, research centered in East Africa. The couple Mary and Louis Leakey discovered a major site at Olduvai Gorge, in Tanzania:

- many seasons of excavations at this site - discovery of many layers (called beds), with essential collection of faunal remains and stone tools, and several hominid species identified for the first time there;

- In 1959, discovery in Bed I of hominid remains (OH5), named Zinjanthropus (Australopithecus) boisei;

- L. Leakey first considered this hominid as the author of stone tools, until he found (in 1964) other hominid fossils in the same Bed I, which he attributed to different species - Homo habilis (OH7).

Another major discovery of paleoanthropological interest comes from the Omo Valley in Ethiopia:

- from 1967 to 1976, nine field seasons were carried out;

- In 1967, discovery of hominid fossils attributed to new species - Australopithecus aethiopicus

- 217 specimens of hominid fossils attributed to five hominid species: A. afarensis, A. aethiopicus, A. boisei, H. rudolfensis, H. erectus, dated to between 3.3 and 1 Million years ago.

Also in 1967, Richard Leakey starts survey and excavation on the east shore of Lake Turkana (Kenya), at a location called Koobi Fora:

- research carried out between 1967 and 1975

- very rich collection of fossils identified, attributed to A. afarensis and A. boisei

In 1972, a French-American expedition led by Donald Johanson and Yves Coppens focuses on a new locality (Hadar region) in the Awash Valley (Ethiopia):

- research carried out between 1972-1976

- in 1973, discovery of most complete skeleton to date, named Lucy, attributed (in 1978 only) to A. afarensis

- more than 300 hominid individuals were recovered

- discoveries allow for a detailed analysis of locomotion and bipedalism among early hominids

From 1976 to 1979, Mary Leakey carries out research at site of Laetoli, in Tanzania:

- In 1976, she discovers animal footprints preserved in tuff (volcanic ash), dated to 3.7 million years ago (MYA).

- In 1978-1979, discovery of site with three series of hominid (australopithecine) footprints, confirming evidence of bipedalism.

1980 - The Present

South Africa

Four australopithecine foot bones dated at around 3.5 million years were found at Sterkfontein in 1994 by Ronald Clarke:

- oldest hominid fossils yet found in South Africa

- They seem to be adapted to bipedalism, but have an intriguing mixture of ape and human features

Since then, eight more foot and leg bones have been found from the same individual, who has been nicknamed "Little Foot".

Eastern Africa

Recent discovery of new A. boisei skull is:

- one of the most complete known, and the first known with an associated cranium and lower jaw;

- It also has a surprising amount of variability from other A. boisei skulls, which may have implications for how hominid fossils are classified.

Recent research suggests that the some australopithecines were capable of a precision grip, like that of humans but unlike apes, which would have meant they were capable of making stone tools.

The oldest known stone tools have been found in Ethiopia in sediments dated at between 2.5 million and 2.6 million years old. The makers are unknown, but may be either early Homo or A. garhi

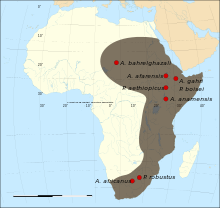

A main question is, how have these species come to exist in the geographical areas so far apart from one another?

Chad

A partial jaw found in Chad (Central Africa) greatly extends the geographical range in which australopithecines are known to have lived. The specimen (nicknamed Abel) has been attributed to a new species - Australopithecus bahrelghazali.

In June 2002, publication of major discovery of earliest hominid known: Sahelanthropus tchadensis (nickname: "Toumai").

Bone Identification and Terminology

Skull

Cranium: The skull minus the lower jaw bone.

Brow, Supraorbital Ridges: Bony protrusions above eye sockets.

Endocranial Volume: The volume of a skull's brain cavity.

Foramen Magnum: The hole in the skull through which the spinal cord passes.

- In apes, it is towards the back of the skull, because of their quadrupedal posture

- In humans it is at the bottom of the skull, because the head of bipeds is balanced on top of a vertical column.

Sagittal Crest: A bony ridge that runs along the upper, outer center line of the skull to which chewing muscles attach.

Subnasal Prognathism: Occurs when front of the face below the nose is pushed out.

Temporalis Muscles: The muscles that close the jaw.

Teeth

Canines, Molars: Teeth size can help define species.

- Gorillas eat lots of foliage; therefore they need very large molars, they also have pronounced canines.

- Humans are omnivorous and have smaller more generalized molars, and reduced canines.

Dental Arcade: The rows of teeth in the upper and lower jaws.

- Chimpanzees have a narrow, U-shaped dental arcade

- Modern humans have a wider, parabolic dental arcade

- The dental arcade of Australopithecus afarensis has an intermediate V shape

Diastema: Functional gaps between teeth.

- In the chimpanzee's jaw, the gap between the canine and the neighboring incisor, which provides a space for the opposing canine when the animal's mouth is closed

- Modern humans have small canines and no diastema.

Using Bones to Define Humans

Bipedalism

Fossil pelvic and leg bones, body proportions, and footprints all read "bipeds." The fossil bones are not identical to modern humans, but were likely functionally equivalent and a marked departure from those of quadrupedal chimpanzees.

Australopithecine fossils possess various components of the bipedal complex which can be compared to those of chimpanzees and humans:

- A diagnostic feature of bipedal locomotion is a shortened and broadened ilium (or large pelvic bone); the australopithecine ilium is shorter than that of apes, and it is slightly curved; this shape suggests that the gluteal muscles were in a position to rotate and support the body during bipedal walking

- In modern humans, the head of the femur (or thigh bone) is robust, indicating increased stability at this joint for greater load bearing

- In humans, the femur angles inward from the hip to the knee joint, so that the lower limbs stand close to the body's midline. The line of gravity and weight are carried on the outside of the knee joint; in contrast, the chimpanzee femur articulates at the hip, then continues in a straight line downward to the knee joint

- The morphology of the australopithecine femur is distinct and suggests a slightly different function for the hip and knee joints. The femoral shaft is angled more than that of a chimpanzee and indicates that the knees and feet were well planted under the body

- In modern humans, the lower limbs bear all the body weight and perform all locomotor functions. Consequently, the hip, knee and ankle joint are all large with less mobility than their counterparts in chimpanzees. In australopithecines, the joints remain relatively small. In part, this might be due to smaller body size. It may also be due to a unique early hominid form of bipedal locomotion that differed somewhat from that of later hominids.

Thus human bodies were redesigned by natural selection for walking in an upright position for longer distances over uneven terrain. This is potentially in response to a changing African landscape with fewer trees and more open savannas.

Brain Size

Bipedal locomotion became established in the earliest stages of the hominid lineage, about 7 million years ago, whereas brain expansion came later. Early hominids had brains slightly larger than those of apes, but fossil hominids with significantly increased cranial capacities did not appear until about 2 million years ago.

Brain size remains near 450 cubic centimetres (cc) for robust australopithecines until almost 1.5 million years ago. At the same time, fossils assigned to Homo exceed 500 cc and reach almost 900 cc.

What might account for this later and rapid expansion of hominid brain size? One explanation is called the "radiator theory": a new means for cooling this vital heat-generating organ, namely a new pattern of cerebral blood circulation, would be responsible for brain expansion in hominids. Gravitational forces on blood draining from the brain differ in quadrupedal animals versus bipedal animals: when humans stand bipedally, most blood drains into veins at the back of the neck, a network of small veins that form a complex system around the spinal column.

The two different drainage patterns might reflect two systems of cooling brains in early hominids. Active brains and bodies generate a lot of metabolic heat. The brain is a hot organ, but must maintain a fairly rigid temperature range to keep it functioning properly and to prevent permanent damage.

Savanna-dwelling hominids with this network of veins had a way to cool a bigger brain, allowing the "engine" to expand, contributing to hominid flexibility in moving into new habitats and in being active under a wide range of climatic conditions.

Free Hands

Unlike other primates, hominids no longer use their hands in locomotion or bearing weight or swinging through the trees. The chimpanzee's hand and foot are similar in size and length, reflecting the hand's use for bearing weight in knuckle walking. The human hand is shorter than the foot, with straighter phalanges. Fossil hand bones two million to three million years old reveal this shift in specialization of the hand from locomotion to manipulation.

Chimpanzee hands are a compromise. They must be relatively immobile in bearing weight during knuckle walking, but dexterous for using tools. Human hands are capable of power and precision grips but more importantly are uniquely suited for fine manipulation and coordination.

Tool Use

Fossil hand bones show greater potential for evidence of tool use. Although no stone tools are recognizable in an archaeological context until 2.5 million years ago, we can infer nevertheless their existence for the earliest stage of human evolution. The tradition of making and using tools almost certainly goes back much earlier to a period of utilizing unmodified stones and tools mainly of organic, perishable materials (wood or leaves) that would not be preserved in the fossil record.

How can we tell a hominid-made artifact from a stone generated by natural processes? First, the manufacturing process of hitting one stone with another to form a sharp cutting edge leaves a characteristic mark where the flake has been removed. Second, the raw material for the tools often comes from some distance away and indicates transport to the site by hominids.

Modification of rocks into predetermined shapes was a technological breakthrough. Possession of such tools opened up new possibilities in foraging: for example, the ability to crack open long bones and get at the marrow, to dig, and to sharpen or shape wooden implements.

Even before the fossil record of tools around 2.5 Myrs, australopithecine brains were larger than chimpanzee brains, suggesting increased motor skills and problem solving. All lines of evidence point to the importance of skilled making and using of tools in human evolution.

Summary

In this chapter, we learned the following:

1. Humans clearly depart from apes in several significant areas of anatomy, which stem from adaptation:

- bipedalism

- dentition (tooth size and shape)

- free hands

- brain size

2. For most of human evolution, cultural evolution played a fairly minor role. If we look back at the time of most australopithecines, it is obvious that culture had little or no influence on the lives of these creatures, who were constrained and directed by the same evolutionary pressures as the other organisms with which they shared their ecosystem. So, for most of the time during which hominids have existed, human evolution was no different from that of other organisms.

3. Nevertheless once our ancestors began to develop a dependence on culture for survival, then a new layer was added to human evolution. Sherwood Washburn suggested that the unique interplay of cultural change and biological change could account for why humans have become so different. According to him, as culture became more advantageous for the survival of our ancestors, natural selection favoured the genes responsible for such behaviour. These genes that improved our capacity for culture would have had an adaptive advantage. We can add that not only the genes but also anatomical changes made the transformations more advantageous. The ultimate result of the interplay between genes and culture was a significant acceleration of human evolution around 2.6 million to 2.5 million years ago.

Overview of Human Evolutionary Origin

The fossil record provides little information about the evolution of the human lineage during the Late Miocene, from 10 million to 5 million years ago. Around 10 million years ago, several species of large-bodied hominids that bore some resemblance to modern orangutans lived in Africa and Asia. About this time, the world began to cool; grassland and savanna habitats spread; and forests began to shrink in much of the tropics.

The creatures that occupied tropical forests declined in variety and abundance, while those that lived in the open grasslands thrived. We know that at least one ape species survived the environmental changes that occurred during the Late Miocene, because molecular genetics tells us that humans, gorillas, bonobos and chimpanzees are all descended from a common ancestor that lived sometime between 7 million and 5 million years ago. Unfortunately, the fossil record for the Late Miocene tells us little about the creature that linked the forest apes to modern hominids.

Beginning about 5 million years ago, hominids begin to appear in the fossil record. These early hominids were different from any of the Miocene apes in one important way: they walked upright (as we do). Otherwise, the earliest hominids were probably not much different from modern apes in their behavior or appearance.

Between 4 million and 2 million years ago, the hominid lineage diversified, creating a community of several hominid species that ranged through eastern and southern Africa. Among the members of this community, two distinct patterns of adaptation emerged:

- One group of creatures (Australopithecus, Ardipithecus, Paranthropus) evolved large molars that enhanced their ability to process coarse plant foods;

- The second group, constituted of members of our own genus Homo (as well as Australopithecus garhi) evolved larger brains, manufactured and used stone tools, and relied more on meat than the Australopithecines did.

Hominid Species

| Species | Type | Specimen | Named by |

| Sahelanthropus | tchadensis "Toumai" | TM 266-01-060-1 | Brunet et al. 2002 |

| Orrorin | tugenensis | BAR 1000'00 | Senut et al. 2001 |

| Ardipithecus | ramidus | ARA-VP 6/1 | White et al. 1994 |

| Australopithecus | anamensis | KP 29281 | M. Leakey et al. 1995 |

| Australopithecus | afarensis | LH 4 | Johanson et al. 1978 |

| Australopithecus | bahrelghazali | KT 12/H1 | Brunet et al. 1996 |

| Kenyanthropus | platyops | KNM-WT 40000 | M. Leakey et al. 2001 |

| Australopithecus | garhi | BOU-VP-12/130 | Asfaw et al. 1999 |

| Australopithecus | africanus | Taung | Dart 1925 |

| Australopithecus | aethiopicus | Omo 18 | Arambourg & Coppens 1968 |

| Paranthropus | robustus | TM 1517 | Broom 1938 |

| Paranthropus | boisei | OH 5 | L. Leakey 1959 |

| Homo | habilis | OH 7 | L. Leakey et al. 1964 |

Sahelanthropus tchadensis ("Toumai")

- Named in July 2002 from fossils discovered in Chad.

- Oldest known hominid or near-hominid species (6-7 million years ago).

- Discovery of nearly complete cranium and number of fragmentary lower jaws and teeth:

- Skull has very small brain size (ca. 350 cc), considered as primitive apelike feature;

- Yet, other features are characteristic of later hominids: short and relatively flat face; canines are smaller and shorter; tooth enamel is slightly thicker (suggesting a diet with less fruit).

- This mixture of features, along with fact that it comes from around the time when hominids are thought to have diverged from chimpanzees, suggests it is close to the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees.

- Foramen magnum is oval (not rounded as in chimps) suggesting upright walking position.

Orrorin tugenensis

- Named in July 2001; fossils discovered in western Kenya.

- Deposits dated to about 6 million years ago.

- Fossils include fragmentary arm and thigh bones, lower jaws, and teeth:

- Limb bones are about 1.5 times larger than those of Lucy, and suggest that it was about the size of a female chimpanzee.

- Its finders claimed that Orrorin was a human ancestor adapted to both bipedality and tree climbing, and that the australopithecines are an extinct offshoot.

Ardipithecus ramidus

- Recent discovery announced in Sept. 1994.

- Dated 4.4 million years ago.

- Most remains are skull fragments.

- Indirect evidence suggests that it was possibly bipedal, and that some individuals were about 122 cm (4'0") tall;

- Teeth are intermediate between those of earlier apes and Austalopithecus afarensis.

Australopithecus anamensis

- Named in August 1995 from fossils from Kanapoi and Allia Bay in Kenya.

- Dated between 4.2 and 3.9 million years ago.

- Fossils show mixture of primitive features in the skull, and advanced features in the body:

- Teeth and jaws are very similar to those of older fossil apes;

- Partial tibia (inner calf bone) is strong evidence of bipedality, and lower humerus (the upper arm bone) is extremely humanlike.

Australopithecus afarensis

- Existed between 3.9 and 3.0 million years ago.

- A. afarensis had an apelike face with a low forehead, a bony ridge over the eyes, a flat nose, and no chin. They had protruding jaws with large back teeth.

- Cranial capacity: 375 to 550 cc. Skull is similar to chimpanzee, except for more human-like teeth. Canine teeth are much smaller than modern apes, but larger and more pointed than humans, and shape of the jaw is between rectangular shape of apes and parabolic shape of humans.

- Pelvis and leg bones far more closely resemble those of modern humans, and leave no doubt that they were bipedal.

- Bones show that they were physically very strong.

- Females were substantially smaller than males, a condition known as sexual dimorphism. Height varied between about 107 cm (3'6") and 152 cm (5'0").

- Finger and toe bones are curved and proportionally longer than in humans, but hands are similar to humans in most other details.

Kenyanthropus platyops ("flat-faced man of Kenya")

- Named in 2001 from partial skull found in Kenya.

- Dated to about 3.5 million years ago.

- Fossils show unusual mixture of features: size of skull is similar to A. afarensis and A. africanus, and has a large, flat face and small teeth.

Australopithecus garhi

- A. garhi existed around 2.5 Myrs.

- It has an apelike face in the lower part, with a protruding jaw resembling that of A. afarensis. The large size of the palate and teeth suggests that it is a male, with a small braincase of about 450 cc.

- It is like no other hominid species and is clearly not a robust form. In a few dental traits, such as the shape of the premolar and the size ratio of the canine teeth to the molars, A. garhi resembles specimens of early Homo. But its molars are huge, even larger than the A. robustus average.

- Among skeletal finds recovered, femur (upper leg bone) is relatively long, like that of modern humans. But forearm is long too, a condition found in apes and other australopithecines but not in humans.

Australopithecus africanus

- First identified in 1924 by Raymond Dart, an Australian anatomist living in South Africa.

- A. africanus existed between 3 and 2 million years ago.

- Similar to A. afarensis, and was also bipedal, but body size was slightly greater.

- Brain size may also have been slightly larger, ranging between 420 and 500 cc. This is a little larger than chimp brains (despite a similar body size).

- Back teeth were a little bigger than in A. afarensis. Although the teeth and jaws of A. africanus are much larger than those of humans, they are far more similar to human teeth than to those of apes. The shape of the jaw is now fully parabolic, like that of humans, and the size of the canine teeth is further reduced compared to A. afarensis.

NOTE: Australopithecus afarensis and A. africanus are known as gracile australopithecines, because of their relatively lighter build, especially in the skull and teeth. (Gracile means "slender", and in paleoanthropology is used as an antonym to "robust"). Despite the use of the word "gracile", these creatures were still more far more robust than modern humans.

Australopithecus aethiopicus

- A. aethiopicus existed between 2.6 and 2.3 million years ago.

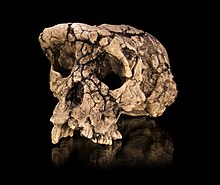

- Species known mainly from one major specimen: the Black Skull (KNM-WT 17000) discovered at Lake Turkana.

- It may be ancestor of P. robustus and P. boisei, but it has a baffling mixture of primitive and advanced traits:

- Brain size is very small (410 cc) and parts of the skull (particularly the hind portions) are very primitive, most resembling A. afarensis;

- Other characteristics, like massiveness of face, jaws and largest sagittal crest in any known hominid, are more reminiscent of P. boisei.

Paranthropus boisei

- P. boisei existed between 2.2 and 1.3 million years ago.

- Similar to P. robustus, but face and cheek teeth were even more massive, some molars being up to 2 cm across. Brain size is very similar to P. robustus, about 530 cc.

- A few experts consider P. boisei and P. robustus to be variants of the same species.

Paranthropus robustus

- P. robustus had a body similar to that of A. africanus, but a larger and more robust skull and teeth.

- It existed between 2 and 1.5 million years ago.

- The massive face is flat, with large brow ridges and no forehead. It has relatively small front teeth, but massive grinding teeth in a large lower jaw. Most specimens have sagittal crests.

- Its diet would have been mostly coarse, tough food that needed a lot of chewing.

- The average brain size is about 530 cc. Bones excavated with P. robustus skeletons indicate that they may have been used as digging tools.

Australopithecus aethiopicus, Paranthropus robustus and P. boisei are known as robust australopithecines, because their skulls in particular are more heavily built.

Homo habilis

- H. habilis ("handy man")

- H. habilis existed between 2.4 and 1.5 million years ago.

- It is very similar to australopithecines in many ways. The face is still primitive, but it projects less than in A. africanus. The back teeth are smaller, but still considerably larger than in modern humans.

- The average brain size, at 650 cc, larger than in australopithecines. Brain size varies between 500 and 800 cc, overlapping the australopithecines at the low end and H. erectus at the high end. The brain shape is also more humanlike.

- H. habilis is thought to have been about 127 cm (5'0") tall, and about 45 kg (100 lb) in weight, although females may have been smaller.

- Because of important morphological variation among the fossils, H. habilis has been a controversial species. Some scientists have not accepted it, believing that all H. habilis specimens should be assigned to either the australopithecines or Homo erectus. Many now believe that H. habilis combines specimens from at least two different Homo species: small-brained less-robust individuals (H. habilis) and large-brained, more robust ones (H. rudolfensis). Presently, not enough is known about these creatures to resolve this debate.

Phylogeny and Chronology

Between 8 million and 4 million years ago

Fossils of Sahelanthropus tchadensis (6-7 million years) and Orrorin tugenensis (6 million years), discovered in 2001 and 2000 respectively, are still a matter of debate.

The discoverers of Orrorin tugenensis claim the fossils represent the real ancestor of modern humans and that the other early hominids (e.g., Australopithecus and Paranthropus) are side branches. They base their claim on their assessment that this hominid was bipedal (2 million years earlier than previously thought) and exhibited expressions of certain traits that were more modern than those of other early hominids. Other authorities disagree with this analysis and some question whether this form is even a hominid. At this point, there is too little information to do more than mention these two new finds of hominids. As new data come in, however, a major part of our story could change.

Fossils of Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4 million years ago) were different enough from any found previously to warrant creating a new hominid genus. Although the evidence from the foramen magnum indicates that they were bipedal, conclusive evidence from legs, pelvis and feet remain somewhat enigmatic. There might be some consensus that A. ramidus represent a side branch of the hominid family.

Between 4 million and 2 million years ago

Australopithecus anamensis (4.2-3.8 million years ago) exhibit mixture of primitive (large canine teeth, parallel tooth rows) and derived (vertical root of canine, thicker tooth enamel) features, with evidence of bipedalism. There appears to be some consensus that this may represent the ancestor of all later hominids.

The next species is well established and its nature is generally agreed upon: Australopithecus afarensis (4-3 million years ago). There is no doubt that A. afarensis were bipeds. This form seems to still remain our best candidate for the species that gave rise to subsequent hominids.

At the same time lived a second species of hominid in Chad: Australopithecus bahrelghazali (3.5-3 million years ago). It suggests that early hominids were more widely spread on the African continent than previously thought. Yet full acceptance of this classification and the implications of the fossil await further study.

Another fossil species contemporaneous with A. afarensis existed in East Africa: Kenyanthropus platyops (3.5 million years ago). The fossils show a combination of features unlike that of any other forms: brain size, dentition, details of nasal region resemble genus Australopithecus; flat face, cheek area, brow ridges resemble later hominids. This set of traits led its discoverers to give it not only a new species name but a new genus name as well. Some authorities have suggested that this new form may be a better common ancestor for Homo than A. afarensis. More evidence and more examples with the same set of features, however, are needed to even establish that these fossils do represent a whole new taxonomy.

Little changed from A. afarensis to the next species: A. africanus: same body size and shape, and same brain size. There are a few differences, however: canine teeth are smaller, no gap in tooth row, tooth row more rounded (more human-like).

We may consider A. africanus as a continuation of A. afarensis, more widely distributed in southern and possibly eastern Africa and showing some evolutionary changes. It should be noted that this interpretation is not agreed upon by all investigators and remains hypothetical.

Fossils found at Bouri in Ethiopia led investigators to designate a new species: A. garhi (2.5 million years ago). Intriguing mixture of features: several features of teeth resemble early Homo; whereas molars are unusually larger, even larger than the southern African robust australopithecines.

The evolutionary relationship of A. garhi to other hominids is still a matter of debate. Its discoverers feel it is descended from A. afarensis and is a direct ancestor to Homo. Other disagree. Clearly, more evidence is needed to interpret these specimens more precisely, but they do show the extent of variation among hominids during this period.

Two distinctly different types of hominid appear between 2 and 3 million years ago: robust australopithecines (Paranthropus) and early Homo (Homo habilis).

The first type retains the chimpanzee-sized brains and small bodies of Australopithecus, but has evolved a notable robusticity in the areas of the skull involved with chewing: this is the group of robust australopithecines (A. boisei, A. robustus, A. aethiopicus).

- The Australopithecines diet seems to have consisted for the most part of plant foods, although A. afarensis, A. africanus and A. garhi may have consumed limited amounts of animal protein as well;

- Later Australopithecines (A. boisei and robustus) evolved into more specialized "grinding machines" as their jaws became markedly larger, while their brain size did not.

The second new hominid genus that appeared about 2.5 million years ago is the one to which modern humans belong, Homo.

- A Consideration of brain size relative to body size clearly indicates that Homo habilis had undergone enlargement of the brain far in excess of values predicted on the basis of body size alone. This means that there was a marked advance in information-processing capacity over that of Australopithecines;

- Although H. habilis had teeth that are large by modern standard, they are smaller in relation to the size of the skull than those of Australopithecines. Major brain-size increase and tooth-size reduction are important trends in the evolution of the genus Homo, but not of Australopithecines;

- From the standpoint of anatomy alone, it has long been recognized that either A. afarensis or A. africanus constitute a good ancestor for the genus Homo, and it now seems clear that the body of Homo habilis had changed little from that of either species. Precisely which of the two species gave rise to H. habilis is vigorously debated. Whether H. habilis is descended from A. afarensis, A. africanus, both of them, or neither of them, is still a matter of debate. It is also possible that none of the known australopithecines is our ancestor. The discoveries of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Orrorin tugenensis, and A. anamensis are so recent that it is hard to say what effect they will have on current theories.

What might have caused the branching that founded the new forms of robust australopithecines (Paranthropus) and Homo? What caused the extinction, around the same time (between 2-3 million years ago) of genus Australopithecus? Finally, what might have caused the extinction of Paranthropus about 1 million years ago?

No certainty in answering these questions. But the environmental conditions at the time might hold some clues. Increased environmental variability, starting about 6 million years ago and continuing through time and resulting in a series of newly emerging and diverse habitats, may have initially promoted different adaptations among hominid populations, as seen in the branching that gave rise to the robust hominids and to Homo.

And if the degree of the environmental fluctuations continued to increase, this may have put such pressure on the hominid adaptive responses that those groups less able to cope eventually became extinct. Unable to survive well enough to perpetuate themselves in the face of decreasing resources (e.g., Paranthropus, who were specialized vegetarians) these now-extinct hominids were possibly out-competed for space and resources by the better adapted hominids, a phenomenon known as competitive exclusion.

In this case, only the adaptive response that included an increase in brain size, with its concomitant increase in ability to understand and manipulate the environment, proved successful in the long run.

Hominoid, Hominid, Human

The traditional view has been to recognize three families of hominoid: the Hylobatidae (Asian lesser apes: gibbons and siamangs), the Pongidae, and the Hominidae.

- The Pongidae include the African great apes, including gorillas, chimpanzees and the Asian orangutans;

- The Hominidae include living humans and typically fossil apes that possess a suite of characteristics such as bipedalism, reduced canine size, and increasing brain size (e.g., australopithecines).

The emergence of hominoids

Hominoids are Late Miocene (15-5 million years ago) primates that share a small number of postcranial features with living apes and humans:

- no tail;

- pelvis lacks bony expansion;

- elbow similar to that of modern apes;

- somewhat larger brains in relationship to body size than similarly sized monkeys.

When is a hominoid also a hominid?

When we say that Sahelanthropus tchadensis is the earliest hominid, we mean that it is the oldest fossil that is classified with humans in the family Hominidae. The rationale for including Sahelanthropus tchadensis in the Hominidae is based on similarities in shared derived characters that distinguish humans from other living primates.

There are three categories of traits that separate hominids from contemporary apes:

- bipedalism;

- much larger brain in relation to body size;

- dentition and musculature.

To be classified as a hominid, a Late Miocene primate (hominoid) must display at least some of these characteristics. Sahelanthropus tchadensis is bipedal, and shares many dental features with modern humans. However, the brain of Sahelanthropus tchadensis was no bigger than that of contemporary chimpanzees. As a consequence, this fossil is included in the same family (Hominidae) as modern humans, but not in the same genus.

Traits defining early Homo

Early Homo (e.g., Homo habilis) is distinctly different from any of the earliest hominids, including the australopithecines, and similar to us in the following ways:

- brain size is substantially bigger than that of any of the earliest hominids, including the australopithecines;

- teeth are smaller, enamel thinner, and the dental arcade is more parabolic than is found in the earliest hominids, including the australopithecines;

- skulls are more rounded; the face is smaller and protrudes less, and the jaw muscles are reduced compared with earliest hominids, including the australopithecines.

One of the most important and intriguing questions in human evolution is about the diet of our earliest ancestors. The presence of primitive stone tools in the fossil record tells us that 2.5 million years ago, early hominids (A. garhi) were using stone implements to cut the flesh off the bones of large animals that they had either hunted or whose carcasses they had scavenged.

Earlier than 2.5 million years ago, however, we know very little about the foods that the early hominids ate, and the role that meat played in their diet. This is due to lack of direct evidence. Nevertheless, paleoanthropologists and archaeologists have tried to answer these questions indirectly using a number of techniques.

- Primatology (studies on chimpanzee behavior)

- Anatomical Features (tooth morphology and wear-patterns)

- Isotopic Studies (analysis of chemical signatures in teeth and bones)

What does chimpanzee food-consuming behavior suggest about early hominid behavior?

Meat consuming strategy

Earliest ancestors and chimpanzees share a common ancestor (around 5-7 million years ago). Therefore, understanding chimpanzee hunting behavior and ecology may tell us a great deal about the behavior and ecology of those earliest hominids.

In the early 1960s, when Jane Goodall began her research on chimpanzees in Gombe National Park (Tanzania), it was thought that chimpanzees were herbivores. In fact, when Goodall first reported meat hunting by chimpanzees, many people were extremely sceptical.

Today, hunting by chimpanzees at Gombe and other locations in Africa has been well documented.

We now know that each year chimpanzees may kill and eat more than 150 small and medium-sized animals, such as monkeys (red colobus monkey, their favorite prey), but also wild pigs and small antelopes.

Did early hominids hunt and eat small and medium-sized animals? It is quite possible that they did. We know that colobus-like monkeys inhabited the woodlands and riverside gallery forest in which early hominids lived 3-5 Myrs ago. There were also small animals and the young of larger animals to catch opportunistically on the ground.

Many researchers now believe that the carcasses of dead animals were an important source of meat for early hominids once they had stone tools to use (after 2.5 million years ago) for removing the flesh from the carcass. Wild chimpanzees show little interest in dead animals as a food source, so scavenging may have evolved as an important mode of getting food when hominids began to make and use tools for getting at meat.

Before this time, it seems likely that earlier hominids were hunting small mammals as chimpanzees do today and that the role that hunting played in the early hominids' social lives was probably as complex and political as it is in the social lives of chimpanzees.

When we ask when meat became an important part of the human diet, we therefore must look well before the evolutionary split between apes and humans in our own family tree.

Nut cracking

Nut cracking behavior is another chimpanzee activity that can partially reflect early hominin behavior. From Jan. 2006 to May 2006, Susana Carvalho and her colleagues conducted a series of observation on several chimpanzee groups in Bossou and Diecké in Guinea, western Africa. Both direct and indirect observation approach was applied to outdoor laboratory and wild environment scenarios. [1]

The results of this research show three resource-exploitation strategies that chimpanzees apply to utilize lithic material as hammers and anvils to crack nut: 1) Maximum optimization of time and energy (choose the closest spot to process nut). 2) Transport of nuts to a different site or transport of the raw materials for tools to the food. 3) Social strategy such as the behavior of transport of tools and food to a more distant spot. This behavior might relate to sharing of space and resources when various individuals occupy the same area.

The results demonstrate that chimpanzees have similar food exploitation strategies with early hominins which indicate the potential application of primate archaeology to the understanding of early hominin behavior.

What do tooth wear patterns suggest about early hominid behavior?

Bones and teeth in the living person are very plastic and respond to mechanical stimuli over the course of an individual's lifetime. We know, for example, that food consistency (hard vs. soft) has a strong impact on the masticatory (chewing) system (muscles and teeth). Bones and teeth in the living person are therefore tissues that are remarkably sensitive to the environment.

As such, human remains from archaeological sites offer us a retrospective biological picture of the past that is rarely available from other lines of evidence.

Also, new technological advances developed in the past ten years or so now make it possible to reconstruct and interpret in amazing detail the physical activities and adaptations of hominids in diverse environmental settings.

Some types of foods are more difficult to process than others, and primates tend to specialize in different kinds of diets. Most living primates show three basic dietary adaptations:

- insectivores (insect eaters);

- frugivores (fruit eaters);

- folivores (leaf eaters).

Many primates, such as humans, show a combination of these patterns and are called omnivores, which in a few primates includes eating meat.

The ingestion both of leaves and of insects requires that the leaves and the insect skeletons be broken up and chopped into small pieces. The molars of folivores and insectivores are characterized by the development of shearing crests on the molars that function to cut food into small pieces. Insectivores' molars are further characterized by high, pointed cusps that are capable of puncturing the outside skeleton of insects. Frugivores, on the other hand, have molar teeth with low, rounded cusps; their molars have few crests and are characterized by broad, flat basins for crushing the food.

In the 1950s, John Robinson developed what came to be known as the dietary hypothesis. According to this theory there were fundamentally two kinds of hominids in the Plio-Pleistocene. One was the "robust" australopithecine (called Paranthropus) that was specialized for herbivory, and the other was the "gracile" australopithecine that was an omnivore/carnivore. By this theory the former became extinct while the latter evolved into Homo.

Like most generalizations about human evolution, Robinson's dietary hypothesis was controversial, but it stood as a useful model for decades.

Detailed analyses of the tooth surface under microscope appeared to confirm that the diet of A. robustus consisted primarily of plants, particularly small and hard objects like seeds, nuts and tubers. The relative sizes and shapes of the teeth of both A. afarensis and A. africanus indicated as well a mostly mixed vegetable diet of fruits and leaves. By contrast, early Homo was more omnivorous.

But as new fossil hominid species were discovered in East Africa and new analyses were done on the old fossils, the usefulness of the model diminished.

For instance, there is a new understanding that the two South African species (A. africanus and A. robustus) are very similar when compared to other early hominid species. They share a suite of traits that are absent in earlier species of Australopithecus, including expanded cheek teeth and faces remodeled to withstand forces generated from heavy chewing.

What do isotopic studies suggest about early hominid behavior?

Omnivory can be suggested by studies of the stable carbon isotopes and strontium(Sr)-calcium(Ca) ratios in early hominid teeth and bones.

For instance, a recent study of carbon isotope (13C) in the tooth enamel of a sample of A. africanus indicated that members of this species ate either tropical grasses or the flesh of animals that ate tropical grasses or both. But because the dentition analyzed by these researchers lacked the tooth wear patterns indicative of grass-eating, the carbon may have come from grass-eating animals. This is therefore a possible evidence that the australopithecines either hunted small animals or scavenged the carcasses of larger ones.

There is new evidence also that A. robustus might not be a herbivore. Isotopic studies reveal chemical signals associated with animals whose diet is omnivorous and not specialized herbivory. The results from 13C analysis indicate that A. robustus either ate grass and grass seeds or ate animals that ate grasses. Since the Sr/Ca ratios suggest that A. robustus did not eat grasses, these data indicate that A. robustus was at least partially carnivorous.

Summary

Much of the evidence for the earliest hominids (Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Orrorin tugenensis, Ardipithecus ramidus) is not yet available.

Australopithecus anamensis shows the first indications of thicker molar enamel in a hominid. This suggests that A. anamensis might have been the first hominid to be able to effectively withstand the functional demands of hard and perhaps abrasive objects in its diet, whether or not such items were frequently eaten or were only an important occasional food source.

Australopithecus afarensis was similar to A. anamensis in relative tooth sizes and probable enamel thickness, yet it did show a large increase in mandibular robusticity. Hard and perhaps abrasive foods may have become then even more important components of the diet of A. afarensis.

Australopithecus africanus shows yet another increase in postcanine tooth size, which in itself would suggest an increase in the sizes and abrasiveness of foods. However, its molar microwear does not show the degree of pitting one might expect from a classic hard-object feeder. Thus, even A. africanus has evidently not begun to specialize in hard objects, but rather has emphasized dietary breadth (omnivore), as evidenced by isotopic studies.

Subsequent "robust" australopithecines do show hard-object microwear and craniodental specializations, suggesting a substantial departude in feeding adaptive strategies early in the Pleistocene. Yet, recent chemical and anatomical studies on A. robustus suggest that this species may have consumed some animal protein. In fact, they might have specialized on tough plant material during the dry season but had a more diverse diet during the rest of the year.

The Olduvai Gorge

2 million years ago, Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania) was a lake. Its shores were inhabited not only by numerous wild animals but also by groups of hominids, including Paranthropus boisei and Homo habilis, as well as the later Homo erectus.

The gorge, therefore, is a great source of Palaeolithic remains as well as a key site providing evidence of human evolutionary development. This is one of the main reasons that drew Louis and Mary Leakey back year after year at Olduvai Gorge.

Certain details of the lives of the creatures who lived at Olduvai have been reconstructed from the hundreds of thousands of bits of material that they left behind: various stones and bones. No one of these things, alone, would mean much, but when all are analyzed and fitted together, patterns begin to emerge.

Among the finds are assemblages of stone tools dated to between 2.2 Myrs and 620,000 years ago. These were found little disturbed from when they were left, together with the bones of now-extinct animals that provided food.

Mary Leakey found that there were two stoneworking traditions at Olduvai. One, the Acheulean industry, appears first in Bed II and lasts until Bed IV. The other, the Oldowan, is older and more primitive, and occurs throughout Bed I, as well as at other African sites in Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania.

Subsistence patterns

Meat-eating

Until about 2.5 million years ago, early hominids lived on foods that could be picked or gathered: plants, fruits, invertebrate animals such as ants and termites, and even occasional pieces of meat (perhaps hunted in the same manner as chimpanzees do today).

After 2.5 million years ago, meat seems to become more important in early hominids' diet. Evolving hominids' new interest in meat is of major importance in paleoanthropology.

Out on the savanna, it is hard for a primate with a digestive system like that of humans to satisfy its amino-acid requirements from available plant resources. Moreover, failure to do so has serious consequences: growth depression, malnutrition, and ultimately death. The most readily accessible plant resources would have been the proteins accessible in leaves and legumes, but these are hard for primates like us to digest unless they are cooked. In contrast, animal foods (ants, termites, eggs) not only are easily digestible, but they provide high-quantity proteins that contain all the essential amino acids. All things considered, we should not be surprised if our own ancestors solved their "protein problem" in somewhat the same way that chimps on the savanna do today.

Increased meat consumption on the part of early hominids did more than merely ensure an adequate intake of essential amino acids. Animals that live on plant foods must eat large quantities of vegetation, and obtaining such foods consumes much of their time. Meat eaters, by contrast, have no need to eat so much or so often. Consequently, meat-eating hominids may have had more leisure time available to explore and manipulate their environment, and to lie around and play. Such activities probably were a stimulus to hominid brain development.

The importance of meat eating for early hominid brain development is suggested by the size of their brains:

- cranial capacity of largely plant-eating Australopithecus ranged from 310 to 530 cc;

- cranial capacity of primitive known meat eater, Homo habilis: 580 to 752 cc;

- Homo erectus possessed a cranial capacity of 775 to 1,225 cc.

Hunters or scavengers?

The archaeological evidence indicates that Oldowan hominids ate meat. They processed the carcasses of large animals, and we assume that they ate the meat they cut from the bones. Meat-eating animals can acquire meat in several different ways:

- stealing kills made by other animals;

- by opportunistically exploiting the carcasses of animals that die naturally;

- by hunting or capturing prey themselves.

There has been considerable dispute among anthropologists about how early hominids acquired meat. Some have argued that hunting, division of labor, use of home bases and food sharing emerged very early in hominid history. Others think the Oldowan hominids would have been unable to capture large mammals because they were too small and too poorly armed.

Recent zooarchaeological evidence suggests that early hominids (after 2.5 million years ago) may have acquired meat mainly by scavenging, and maybe occasionally by hunting.

If hominids obtained most of their meat from scavenging, we would expect to find cut marks mainly on bones left at kill sites by predators (lions, hyenas). If hominids obtained most of their meat from their own kills, we would expect to find cut marks mainly on large bones, like limb bones. However, at Olduvai Gorge, cut marks appear on both kinds of bones: those usually left by scavengers and those normally monopolized by hunters. The evidence from tool marks on bones indicates that humans sometimes acquired meaty bones before, and sometimes after, other predators had gnawed on them.

Settlement patterns

During decades of work at Olduvai Gorge, Mary and Louis Leakey and their team laid bare numerous ancient hominid sites. Sometimes the sites were simply spots where the bones of one or more hominid species were discovered. Often, however, hominid remains were found in association with concentrations of animal bones, stone tools, and debris.

At one spot, in Bed I, the bones of an elephant lay in close association with more than 200 stone tools. Apparently, the animal was butchered here; there are no indications of any other activity.

At another spot (DK-I Site), on an occupation surface 1.8 million years old, basalt stones were found grouped in small heaps forming a circle. The interior of the circle was practically empty, while numerous tools and food debris littered the ground outside, right up to the edge of the circle.

Earliest stone industry

Principles

Use of specially made stone tools appears to have arisen as result of need for implements to butcher and prepare meat, because hominid teeth were inadequate for the task. Transformation of lump of stone into a "chopper", "knife" or "scraper" is a far cry from what a chimpanzee does when it transforms a stick into a termite probe. The stone tool is quite unlike the lump of stone. Thus, the toolmaker must have in mind an abstract idea of the tool to be made, as well as a specific set of steps that will accomplish the transformation from raw material to finished product. Furthermore, only certain kinds of stone have the flaking properties that will allow the transformation to take place, and the toolmaker must know about these.

Therefore, two main components to remember:

- Raw material properties

- Flaking properties

Evidence

The oldest Lower Palaeolithic tools (2.0-1.5 million years ago) found at Olduvai Gorge (Homo habilis) are in the Oldowan tool tradition. Nevertheless, older materials (2.6-2.5 million year ago) have recently been recorded from sites located in Ethiopia (Hadar, Omo, Gona, Bouri - Australopithecus garhi) and Kenya (Lokalalei).

Because of a lack of remarkable differences in the techniques and styles of artifact manufacture for over 1 million years (2.6-1.5 million years ago), a technological stasis was suggested for the Oldowan Industry.

The makers of the earliest stone artifacts travelled some distances to acquire their raw materials, implying greater mobility, long-term planning and foresight not recognized earlier.

Oldowan stone tools consist of all-purpose generalized chopping tools and flakes. Although these artifacts are very crude, it is clear that they have been deliberately modified. The technique of manufacture used was the percussion.

The main intent of Oldowan tool makers was the production of cores and flakes with sharp-edges. These simple but effective Oldowan choppers and flakes made possible the addition of meat to the diet on a regular basis, because people could now butcher meat, skin any animal, and split bones for marrow.

Overall, the hominids responsible for making these stone tools understood the flaking properties of the raw materials available; they selected appropriate cobbles for making artifacts; and they were as competent as later hominids in their knapping abilities.

Finally, the manufacture of stone tools must have played a major role in the evolution of the human brain, first by putting a premium on manual dexterity and fine manipulation over mere power in the use of the hands. This in turn put a premium in the use of the hands.

Early hominid behavior

During the 1970s and 1980s many workers, including Mary Leakey and Glynn Isaac, used an analogy from modern hunter-gatherer cultures to interpret early hominid behavior of the Oldowan period (e.g., the Bed I sites at Olduvai Gorge). They concluded that many of the sites were probably camps, often called "home bases", where group members gathered at the end of the day to prepare and share food, to socialize, to make tools, and to sleep.

The circular concentration of stones at the DK-I site was interpreted as the remains of a shelter or windbreak similar to those still made by some African foraging cultures. Other concentrations of bones and stones were thought to be the remains of living sites originally ringed by thorn hedges for defense against predators. Later, other humanlike elements were added to the mix, and early Homo was described as showing a sexual division of labor [females gathering plant foods and males hunting for meat] and some of the Olduvai occupation levels were interpreted as butchering sites.

Views on the lifestyle of early Homo began to change in the late 1980s, as many scholars became convinced that these hominids had been overly humanized.

Researchers began to show that early Homo shared the Olduvai sites with a variety of large carnivores, thus weakening the idea that these were the safe, social home bases originally envisioned.

Studies of bone accumulations suggested that H. habilis was mainly a scavenger and not a full-fledged hunter. The bed I sites were interpreted as no more than "scavenging stations" where early Homo brought portions of large animal carcasses for consumption.

Another recent suggestion is that the Olduvai Bed I sites mainly represent places where rocks were cached for the handy processing of animal foods obtained nearby. Oldowan toolmakers brought stones from sources several kilometers away and cached them at a number of locations within the group's territory. Stone tools could have been made at the cache sites for use elsewhere, but more frequently portions of carcasses were transported to the toolmaking site for processing.

Summary

Current interpretations of the subsistence, settlement, and tool-use patterns of early hominids of the Oldowan period are more conservative than they have been in the past. Based upon these revised interpretations, the Oldowan toolmakers have recently been dehumanized.

Although much more advanced than advanced apes, they still were probably quite different from modern people with regard to their living arrangements, methods and sexual division of food procurement and the sharing of food.

The label human has to await the appearance of the next representative of the hominid family: Homo erectus.

In 1866, German biologist Ernst Haeckel had proposed the generic name "Pithecanthropus" for a hypothetical missing link between apes and humans.

In late 19th century, Dutch anatomist Eugene Dubois was on the Indonesian island of Java, searching for human fossils. In the fall of 1891, he encountered the now famous Trinil skull cap. The following year his crew uncovered a femur, a left thigh bone, very similar to that of modern humans. He was convinced he had discovered an erect, apelike transitional form between apes and humans. In 1894, he decided to call his fossil species Pithecanthropus erectus. Dubois found no additional human fossils and he returned to the Netherlands in 1895.

Others explored the same deposits on the island of Java, but new human remains appeared only between 1931 and 1933.

Dubois's claim for a primitive human species was further reinforced by nearly simultaneous discoveries from near Beijing, China (at the site of Zhoukoudian). Between 1921 and 1937, various scholars undertook fieldwork in one collapsed cave (Locality 1) recovered many fragments of mandibles and skulls. One of them, Davidson Black, a Canadian anatomist, created a new genus and species for these fossils: Sinanthropus pekinensis ("Peking Chinese man").

In 1939, after comparison of the fossils in China and Java, some scholars concluded that they were extremely similar. They even proposed that Pithecanthropus and Sinanthropus were only subspecies of a single species, Homo erectus, though they continued to use the original generic names as labels.

From 1950 to 1964, various influential authorities in paleoanthropology agreed that Pithecanthropus and Sinanthropus were too similar to be placed in two different genera; and, by the late 1960s, the concept of Homo erectus was widely accepted.

To the East Asian inventory of H. erectus, many authorities would add European and especially African specimens that resembled the Asian fossil forms. In 1976, a team led by Richard Leakey discovered around Lake Turkana (Kenya) an amazingly well-preserved and complete skeleton of a H. erectus boy, called the Turkana Boy (WT-15000).

In 1980s and 1990s:

- new discoveries in Asia (Longgupo, Dmanisi, etc.); in Europe (Atapuerca, Orce, Ceprano);

- precision in chronology and evolution of H. erectus;

- understanding and definition of variability of this species and relationship with other contemporary species.

Site distribution

Africa

Unlike Australopithecines and even Homo habilis, Homo ergaster/erectus was distributed throughout Africa:

- about 1.5 million years ago, shortly after the emergence of H. ergaster, people more intensively occupied the Eastern Rift Valley;

- by 1 million years ago, they had extended their range to the far northern and southern margins of Africa.

Traditionally, Homo erectus has been credited as being the prehistoric pioneer, a species that left Africa about 1 million years ago and began to disperse throughout Eurasia. But several important discoveries in the 1990s have reopened the question of when our ancestors first journeyed from Africa to other parts of the globe. Recent evidence now indicates that emigrant erectus made a much earlier departure from Africa.

Israel

Ubeidiyeh

- Deposits accumulated between 1.4-1.0 million years ago;

- Stone tools of both an early chopper-core (or Developed Oldowan) industry and crude Acheulean-like handaxes. The artifacts closely resemble contemporaneous pieces from Upper Bed II at Olduvai Gorge;

- Rare hominid remains attributed to Homo erectus;

- Ubeidiya might reflect a slight ecological enlargement of Africa more than a true human dispersal.

Gesher Benot Yaaqov

- 800,000 years ago;

- No hominid remains;

- Stone tools are of Acheulean tradition and strongly resemble East African industries.

Republic of Georgia

In 1991, archaeologists excavating a grain-storage pit in the medieval town of Dmanisi uncovered the lower jaw of an adult erectus, along with animal bones and Oldowan stone tools.

Different dating techniques (paleomagnetism, potassium-argon) gave a date of 1.8 million years ago, that clearly antedate that of Ubeidiya. Also the evidence from Dmanisi suggests now a true migration from Africa.

China

Longgupo Cave

- Dated to 1.8 million years ago

- Fragments of a lower jaw belonging either to Homo erectus or an unspecified early Homo.

- Fossils recovered with Oldowan tools.

Zhoukoudian

- Dated between 500,000 and 250,000 years ago.

- Remarkable site for providing large numbers of fossils, tools and other artifacts.

- Fossils of Homo erectus discovered in 1920s and 1930s.

Java

In 1994, report of new dates from sites of Modjokerto and Sangiran where H. erectus had been found in 1891.

Geological age for these hominid remains had been estimated at about 1 million years old. Recent redating of these materials gave dates of 1.8 million years ago for the Modjokerto site and 1.6 million years ago for the Sangiran site.

These dates remained striking due to the absence of any other firm evidence for early humans in East Asia prior to 1 Myrs ago. Yet the individuals from Modjokerto and Sangiran would have certainly traveled through this part of Asia to reach Java.

Europe

Did Homo ergaster/erectus only head east into Asia, altogether bypassing Europe?

Many paleoanthropologists believed until recently that no early humans entered Europe until 500,000 years ago. But the discovery of new fossils from Spain (Atapuerca, Orce) and Italy (Ceprano) secured a more ancient arrival for early humans in Europe.

At Atapuerca, hundreds of flaked stones and roughly eighty human bone fragments were collected from sediments that antedate 780,000 years ago, and an age of about 800,000 years ago is the current best estimate. The artifacts comprise crudely flaked pebbles and simple flakes. The hominid fossils - teeth, jaws, skull fragments - come from several individuals of a new species named Homo antecessor. These craniofacial fragments are striking for derived features that differentiate them from Homo ergaster/erectus, but do not ally them specially with either H. neanderthalensis or H. sapiens.

The hominids

African Homo erectus: Homo ergaster

H. ergaster existed between 1.8 million and 1.3 million years ago.

Like H. habilis, the face shows:

- protruding jaws with large molars;

- no chin;

- thick brow ridges;

- long low skull, with a brain size varying between 750 and 1225 cc.

Early H. ergaster specimens average about 900 cc, while late ones have an average of about 1100 cc. The skeleton is more robust than those of modern humans, implying greater strength.

Body proportions vary:

- Ex. Turkana Boy is tall and slender, like modern humans from the same area, while the few limb bones found of Peking Man indicate a shorter, sturdier build.

Study of the Turkana Boy skeleton indicates that H. ergaster may have been more efficient at walking than modern humans, whose skeletons have had to adapt to allow for the birth of larger-brained infants.

Homo habilis and all the australopithecines are found only in Africa, but H. erectus/ergaster was wide-ranging, and has been found in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Asian Homo erectus

Specimens of H. erectus from Eastern Asia differ morphologically from African specimens:

- features are more exaggerated;

- skull is thicker, brow ridges are more pronounced, sides of skull slope more steeply, the sagittal crest is more exaggerated;

- Asian forms do not show the increase in cranial capacity.

As a consequence of these features, they are less like humans than the African forms of H. erectus.

Paleoanthropologists who study extinct populations are forced to decide whether there was one species or two based on morphological traits alone. They must ask whether eastern and western forms are as different from each other as typical species.

If systematics finally agree that eastern and western populations of H. erectus are distinct species, then the eastern Asian form will keep the name H. erectus. The western forms have been given a new name: Homo ergaster (means "work man") and was first applied to a very old specimen from East Turkana in East Africa.

Homo georgicus

Specimens recovered recently exhibit characteristic H. erectus features: sagittal crest, marked constriction of the skull behind the eyes. But they are also extremely different in several ways, resembling H. habilis:

- small brain size (600 cc);

- prominent browridge;

- projection of the face;

- rounded contour of the rear of skull;

- huge canine teeth.

Some researchers propose that these fossils might represent a new species of Homo: H. georgicus.

Homo antecessor

Named in 1997 from fossils (juvenile specimen) found in Atapuerca (Spain). Dated to at least 780,000 years ago, it makes these fossils the oldest confirmed European hominids.

Mid-facial area of antecessor seems very modern, but other parts of skull (e.g., teeth, forehead and browridges) are much more primitive. Fossils assigned to new species on grounds that they exhibit unknown combination of traits: they are less derived in the Neanderthal direction than later mid-Quaternary European specimens assigned to Homo heidelbergensis.

Homo heidelbergensis

Archaic forms of Homo sapiens first appeared in Europe about 500,000 years ago (until about 200,000 years ago) and are called Homo heidelbergensis.

Found in various places in Europe, Africa and maybe Asia.

This species covers a diverse group of skulls which have features of both Homo erectus and modern humans.

Fossil features:

- brain size is larger than erectus and smaller than most modern humans: averaging about 1200 cc;

- skull is more rounded than in erectus;

- still large brow ridges and receding foreheads;

- skeleton and teeth are usually less robust than erectus, but more robust than modern humans;

- mandible is human-like, but massive and chinless; shows expansion of molar cavities and very long cheek tooth row, which implies a long, forwardly projecting face.

Fossils could represent a population near the common ancestry of Neanderthals and modern humans.

Footprints of H. heidelbergensis (earliest human footprints) have been found in Italy in 2003.

Phylogenic relationships

For almost three decades, paleoanthropologists have often divided the genus Homo among three successive species:

- Homo habilis, now dated between roughly 2.5 Myrs and 1.7 Myrs ago;

- Homo erectus, now placed between roughly 1.7 Myrs and 500,000 years ago;

- Homo sapiens, after 500,000 years ago.

In this view, each species was distinguished from its predecessor primarily by larger brain size and by details of cranio-facial morphology:

- Ex. Change in braincase shape from more rounded in H. habilis to more angular in H. erectus to more rounded again in H. sapiens.

The accumulating evidence of fossils has increasingly undermined a scenario based on three successive species or evolutionary stages. It now strongly favors a scheme that more explicitly recognizes the importance of branching in the evolution of Homo.

This new scheme continues to accept H. habilis as the ancestor for all later Homo. Its descendants at 1.8-1.7 million mears ago may still be called H. erectus, but H. ergaster is now more widely accepted. By 600,000-500,000 years ago, H. ergaster had produced several lines leading to H. neanderthalensis in Europe and H. sapiens in Africa. About 600,000 years ago, both of these species shared a common ancestor to which the name H. heidelbergensis could be applied.

"Out-of-Africa 1" model