IB/Group 3/History/Route 2/Causes and Effects of World War One

Introduction

[edit | edit source]This textbook is structured around the requirements of the 2020 International Baccalaureate History Guide and in particular World history topic 11: Causes and effects of 20th century wars. In order to stop it getting too large and never being finished, this text book only focuses on the causes, practice and effects of World War One. This textbook explores the causes of World War One, as well as the way in which warfare was conducted in different operational theatres. The textbook also looks at World War One as a total war, the use of technology, and the impact these factors had upon the outcome.Teachers should be aware that covering only one war will not be enough for students to be successful in final examinations due to the comparative nature of exam style questions and other wars should be looked at as well. It is hoped that this textbook will be kept updated and modified as the official guides change in the future. It is written as a textbook so there are both questions and examples throughout. Teachers should be aware that exam style questions are not actual past paper questions in case there are any copyright issues with those but rather practice questions written in exam format. Lastly, while the audience for this textbook is primarily students, all textbooks benefit from having teaching guidance explicitly stated throughout rather than in a separate teachers' book (which no-one ever reads), so teaching notes have been added where appropriate.

Task: Introducing the topic

[edit | edit source]Often teachers like to start any new topic with some variation of a "what do you know already" style task typically done with a time limit and then returned to and revised as knowledge develops over the course of study. These type of tasks take various forms from mindmaps to discussions and for those self-studying this can also be a good idea.

- One way a diligent student may choose to structure their "What do you know already about WW1 task is around the "Who?" "What?" "Why" "How?" "When?" questions.

- The wise student will go back to their initial mindmap and keep updating it throughout the course so it becomes an organic visual display of your increasing expertise in the topic

Another pathway for introducing the topic: Teacher led discussion, make sure you give wait time between each question, then think, pair, share and gradually build up the shift from now to 1900

- What makes a super power/great power?

- Who are the great powers in the world now?

- What is a military alliance?

- What are the major alliances or unions of countries now?

- Are there any major military alliances you know of?

- Who do you think were the great powers in 1900?

After students have discussed and you've fed back, introduce the overview.

Overviews

[edit | edit source]After doing the task above, you may wish to read the overview below and/or watch the overview video linked below and then redo/improve your answer to the task above.

1900-1918: From Conquest to Catastrophe

[edit | edit source]At some point in the 1700s Europe began to diverge from the rest of the world in terms of economic might. This great divergence was hastened by the twin impacts of the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution. These political and technological revolutions allowed Europe and her offshoots such as the United States of America, the ability to project military and economic might across the globe on a scale that had not been possible previously. By 1900 much of the world was ruled either indirectly or directly by the Great European Powers and their empires, European dominance was largely unrivaled. These empires which had been built at great benefit to Europe but often at terrible human cost to other parts of the world. These empires would be both a source of rivalry and tension in the build up to war and also an enormous source of manpower and resources for the conflict when it came. Beginning in the Balkans in Europe after the assassination of Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand, WW1 led to the mobilization of more than 70 million military personnel. A conflict on an entirely new scale, that lasted from 1914-1918 the First World War led to an estimated 8.5 million combatant deaths and 13 million civilian deaths directly and millions more indirectly through flu, genocide and continued regional conflicts after its end. It was during WW1 that many of the tactics and strategies of modern warfare were born and WW1 led directly to the fall of three empires, Russia, Germany and Austro-Hungary and must be seen as the final nail in the coffin of a fourth, the Ottoman empire which ended in 1922. The ending carried within it the seeds of the even greater and more destructive conflict that would follow as well as the birth of communism, an ideology whose impact would play a key role in shaping much of the 20th Century.

Task: Source analysis of The Rhodes Colossus Cartoon

- Analyze the source below look for features in the cartoon

- What is the underlying message of the cartoon?

Success criteria

[edit | edit source]As you work through the sections either with a teacher or on your own, as this is a specification specific textbook rather than a general textbook about WW1 it is often useful to keep the examination board success criteria in mind as you plan your answers both for written answers and discussion or debate activities. The following are adapted from the top band of the Paper 2 mark scheme and are useful as general success criteria.

- Responses are clearly focused, showing a high degree of awareness of the demands and implications of the question.

- Responses are well structured and effectively organized.

- Knowledge of the world history topic is accurate and relevant.

- Events are placed in their historical context

- There is a clear understanding of historical concepts.

- The examples that the student chooses to discuss are appropriate and relevant, and are used effectively to support the analysis/evaluation.

- The response makes effective links and/or comparisons (as appropriate to the question).

- The response contains clear and coherent critical analysis.

- There is evaluation of different perspectives, and this evaluation is integrated effectively into the answer.

- All, or nearly all, of the main points are substantiated

- The response argues to a consistent conclusion.

Inquiry questions

[edit | edit source]These are some overarching questions to help structure your study of World War One.

- How do wars between nation-states start?

- To what extent did the long-term causes of the war make conflict likely by 1914?

- How far were the short-term causes to blame for the outbreak of war in 1914?

- To what extent should Germany be blamed for causing the First World War?

- Why did trench warfare develop on the western front and what attempts were there to break the deadlock?

- How far was World War One a world war?

- To what extent did World War One change the world?

- Why are historians still fighting WW1?

Key concepts

[edit | edit source]The IB guide expects students to be familiar with the six historical concepts as these interact with historical knowledge and historical skills to develop a nuanced and sophisticated understanding of the past. They are as follows:

- Change

- Continuity

- Causation

- Consequence

- Significance

- Perspectives

Examples below will demonstrate how to use the key concepts to deepen understanding of the WW1 topic and will be in bold. The key concepts are also excellent ways of structuring your Internal Assessment research question when you come to that.

I. Causes of World War One

[edit | edit source]Long-term causes

[edit | edit source]Unification of Germany and the Franco-Prussian War of 1871

[edit | edit source]The Franco-Prussian war of 1871 led to the defeat of France and the unification of Germany. While defeat in the Franco-Prussian War did led to the birth of revanchism (French for revenge-ism") in France towards Germany this is better seen as a background factor by 1914 rather than a direct cause of war. Particularly upsetting to the French was the territorial loss of Alsace and Lorraine although again that had largely faded as a direct cause of tension by 1914. Stronger links between the Franco-Prussian war and the outbreak of WW1 can be seen in two areas, the first being the creation of a very powerful Germany in the heart of Europe with a strong culture of nationalism and Prussian style militarism. The second was the influence Prussian victory had had on other countries and the resulting move towards larger armies based around the mobilizing of reservists. If you are using MAIN to help you remember the long term causes (and many people do) then this factor would go under either militarism or nationalism.

Militarism

[edit | edit source]The growth of militarism in Europe can be seen as a cause of war in three major ways, firstly the glorification of war as well as a feeling that war was inevitable meant that a military solution and an overly strong influence of serving military officers on political decision making was apparent particularly in Germany. Secondly and linked to this was an increasingly large amount of money being spent on the European militaries and generally an increase in the size of the armies which could be made much larger quickly by calling up reserve forces. Thirdly, the development of new military technology led to a naval arms race between Britain and Germany which further heightened tensions.

The naval arms race

[edit | edit source]Britain's global imperial power was backed by its navy and so when the German Navy Bill of 1900 was passed with a mandate to dramatically increase the size of the German navy, the British saw this as a potential threat to their empire and mastery of the oceans. The British in response launched their own shipbuilding program including the development of a new more powerful class of ship with the launching of the HMS Dreadnought, in 1906. The Dreadnought was a fearsome beast, heavily armoured and capable of striking from large distances and soon both Germany and Britain were rushing to produce them.

Alliance system

[edit | edit source]The development of two rival alliances with two distinct "sides" is often seen as an important linking factor that ensured a local war would grow rapidly to become a global one. By 1914, two different groupings of states had appeared based on a series of treaties and agreements starting with the Dual Alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1879:

- The Triple Alliance: Austria, Germany and Italy

- The Triple Entente: France, Russia and Britain

While the alliances were intended to be defensive they did have the following two major "side effects":

- The countries involved began to think in terms of two opposing sides with some key people beginning to think war was inevitable.

- With France on one side and Russia on the other, Germany now had a potentially hostile power on each side increasing the feeling of encirclement.

Links to external sites discussing alliances

[edit | edit source]Imperial rivalries

[edit | edit source]While imperial rivalries undoubtedly contributed to increased tension between the Great Powers and other states, most notably over the Russo-Japanese war and the Moroccan Crises, and Africa and China were other sources of tension as well. Despite these, it is unlikely that imperial rivalries alone can explain the outbreak of World War One. One of the strongest arguments to show this, is that Britain's huge global empire brought her into conflict with both France in North Africa and Russia at the Indian frontier and yet Britain ended up allied with both powers during WW1. Another example of this is the imperial rivalry between Russia and Japan which had led to the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905 and yet both fought on the same side in World War One. That said, the Germany Kaiser's quest for a "place in the sun" namely more German colonies and particularly the building of a German fleet were undoubtedly unpopular in Britain and seen as a potential future threat to the British empire.

Task: Imperial Rivalries source analysis

[edit | edit source]

Nationalism

[edit | edit source]Nationalism can be defined simply in a belief in the existence of the nation as a political unit. It can however in its extreme forms, be linked to political extremism. Nationalism undeniably played a key role leading up to World War I with Serbian nationalism in particular, playing a key role particularly with its connections to pan-slavic nationalism. It is connected to the outbreak of WW in two major ways: firstly in the Balkans, Serbs sought independence from Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, secondly Serbian nationalism was linked to the use of political violence to further their agenda. These two elements would combine in the assassination of the Archduke of Austria in 1914 by a Bosnian Serb, Gavrillo Princep, which would in turn trigger the start of the Great War.

Revision tasks: Long-term causes

[edit | edit source]- Website: John D Clare's Website is aimed at G9/10 students rather than G11/12 but it is still superbly clear and very useful as you begin the topic or if you find this textbook unclear. Go to this page and see if there's any information about long term causes you would add to the mind map you began at the start of this textbook.

Revision questions: Long-term causes

[edit | edit source]- How important were long-term factors in causing the First World War?

- How significant were the crises of the years 1905 to 1912 in creating tension in Europe?

- What other developments created tension in Europe between 1900 to 1913?

- Define Militarism

- Define Nationalism

- Define Alliances

- Define Imperialism

Short-term causes

[edit | edit source]Assassination of Franz Ferdinand

[edit | edit source]

Video: Did a wrong turn start WW1?

Video: How the assassination of Franz Ferdinand unfolded.

The July Days/Crisis

[edit | edit source]The Blank Cheque

[edit | edit source]The Ultimatum

[edit | edit source]Mobilization

[edit | edit source]Economic causes

[edit | edit source]While economic causes have been stated as a cause of WW1, and in particular conflict over markets and trade, there is little strong evidence that economic factors played more than a contributing role to the outbreak WW1, that said this opinion is disputed by some and another point of view are included below. While it is undoubtedly the case that all the Great Powers and other leading nations did see massive industrial growth during the 19th century particularly with regards to manufacturing, and there were certainly elements of rivalry such as the newly unified Germany beginning to surpass Britain in certain areas, it is harder to make the necessary link between these and the short term causes such as the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, that led to war. Elements of rivalry that did exist were tied to imperialism and competition for access to raw materials and the ability to sell goods overseas. While it is true many countries had introduced customs duties to protect their industries from foreign competition, the economic superpower Britain had remained a free trade nation and other than having the economic might to build and equip huge armies, connecting economic causes directly to the outbreak of war is not easy to do.

Alternative point of view: Economic causes of war from a Marxist perspective

[edit | edit source]In this point of view WW1 was caused by the capitalist economic forces underpinning imperialism leading inevitably to conflict between rival powers. This argument is based on the idea that imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism would inevitably lead to financial monopolies as companies looked for ever increasing profits through the acquisition of new markets, extracting raw materials and exploiting cheap labour from the rest of the world. This would in turn lead to imperial competition and these imperial rivalries would inevitably lead to war. From this perspective World War One should be seen as a ‘capitalist imperialist war’. While simplified for this textbook, this is broadly the line of argument that Lenin would use.

Historiography: Historian Hew Strachan on the Marxist perspective

[edit | edit source]“Even if economic factors are helpful in explaining the long-range causes, it is hard to see how they fit into the precise mechanics of the July crisis itself. Commercial circles in July were appalled at the prospect of war and anticipated the collapse of credit; Bethman Hollweg, the Tsar, and Gray envisaged economic dislocation and social collapse.”[1]

Economic causes: Reflection questions

[edit | edit source]- Why is it hard to make a direct link between economic causes and the outbreak of war in 1914?

- How might a marxist perspective argue economic causes led to war in Europe in 1914?

- According to Strachan what type of causes of WW1 can economic factors not explain?

- What reasoning does he use to support this conclusion?

Ideological causes

[edit | edit source]Political causes

[edit | edit source]Territorial causes

[edit | edit source]Other causes

[edit | edit source]Military planning

[edit | edit source]The Von Schlieffen Plan

[edit | edit source]

Plan XVII/Plan 17

[edit | edit source]Kaiser Wilhelm's personality and actions

[edit | edit source]Historiography

[edit | edit source]Perspectives: Why are historians still fighting WW1?

[edit | edit source]The historiography and the arguments surrounding the causes of WW1 began almost as soon as the war began and continue to this day. This section will give a brief overview of some of the major schools of thought and for those interested in pursuing this topic further there are some links to external sites.

Links to external sites discussing the causes of WW1

[edit | edit source]Revision tasks: Historiography

[edit | edit source]- Read the 10 interpretations from the BBC of who started WW1

- Which one do you agree with the most? Explain your reasoning

- Which one do you agree with the least? Explain your reasoning

- Create your own short answer to the question of "Who was most to blame for the start of WW1?" in the same style as the examples.

Causes of WW1 Review Tasks

[edit | edit source]- Key concept Causation: Watch the Alphonse the Camel Video. Which causes and individuals were most to blame for Alphonse's death? How did the causes combine? Where did responsibility lie?

- Now apply the same reasoning to your knowledge of the causes of WW1 and answer this exam style question: To what extent was Austria-Hungary to blame for the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914?

Causes of WW1 Review Questions

[edit | edit source]These questions can be used in a variety of ways, as quick retrieval practice tasks or even for discussion tasks. If you are planning to use them for retrieval practice make sure you don't look at the answers until you've thought hard about them yourself, even better to have someone ask you the questions and then they can give you feedback on the answers.

- How did global imperialism contribute to tensions in Europe by 1914?

- How far was nationalism the cause of war?

- What were the aims of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s 1890 Weltpolitik policy?

- What was the Schlieffen Plan? What were its aims?

- What was HMS Dreadnought and why was it significant as a cause of WW1?

- How did the Schlieffen Plan play a role in bringing Britain into the war?

- In what ways did the existence of military plans before 1914 contribute to the likelihood of war?

- Give some examples of militarism in Europe prior to 1914

- Why did the naval arms race create tension between Britain and Germany?

- Why was the Austro-Hungarian empire vulnerable to nationalism?

- Why has Kaiser Wilhelm's personality been seen as a cause of war?

- How did the rise in Balkan nationalism contribute to causing the war?

- In your opinion, how significant were a) economic b) ideological c) territorial factors in causing the First World War?

- How important were political reasons in causing the First World War?

- Why did disputes over Morocco increase European tension?

- What are historians' views on the causes of the First World War?

- Did the Alliance System make war more likely or less likely?

- How far did colonial problems create tensions between the Great Powers? Give at least one example

- Why were there problems in the Balkans prior to 1914?

- How did the Alliance System lead to a limited local war in the Balkans expanding into a world war very quickly? Give some examples

Summary of The Causes of World War I

[edit | edit source]< IB | Group 3 | History | Route 2 | Causes, Practices, and Effects of Wars | The Causes of World War I

Franco-Prussian War (1870−1871)

[edit | edit source]- The Prussians hoped to consolidate the smaller states into a new German state; creating a dominant new power head within Europe (as threat to Austria).

- The Prussian Army humiliated France in these Franco-Prussian wars. This was as a result of the effective modern technology such as railways.

- France lost the territory of Alsace-Lorraine and had to pay an indemnity of 5,000 million marks.

- Germany was a new power of Europe and France suffered from political and socio-economic problems following their defeat. This spurred later revenge.

Characteristics of Great European Powers c. 1900

[edit | edit source]Germany

[edit | edit source]- Germany was a democratic monarchy that had a German parliament, The Reichstag, that held limited powers.

- After the Franco-Prussian War, it was the strongest industrial power in Europe, overtaking Britain.

- Suffered from socio-economic problems from the large working class as a result of rapid industrialisation.

- Germany wanted to pursue imperialism and wanted to develop its empire into an overseas empire (colonies in Africa).

- One country stood in its way, Britain.

France

[edit | edit source]- France was a democratic republic with extensive civil liberties.

- Agriculturally based with most civilians living in rural areas.

- Wealthy, and had a large empire.

- Economically unstable as a result of the "swinging economy" before "pacifist" left and "revanchist" right wing parties.

- Wanted Alsace-Lorraine back from Germany.

Britain

[edit | edit source]- Established parliamentary democracy; monarchy retained limited powers.

- Built a vast overseas empire as a result of early industrial revolution - the most powerful international trade of the 19th century.

- The turn of the century meant that the USA and Germany had overtaken in industrial production strength.

- Followed a policy of "Splendid Isolation" in order to circumvent conflicts with other nations.

- Its great navy meant Britain could not attack, only defend and its Navy was the source of its strength.

Austria-Hungary

[edit | edit source]- A dual monarchy that had two heavily bureaucratic and inefficient parliaments.

- Lacked military strength and felt national liberation from states within its empire as a consequence of the growing nationalist forces and ambitions rising within Europe.

- The Slavic people strived fro independence from the Ottomans and wished to unite with the Habsburg Empire.

- "A multi-national European empire within the age of nationalism."

- Russia was the great defender of the Slavic people.

Russia

[edit | edit source]- An autocratic divine monarchy with the Tsar being perceived as having been appointed by God.

- Heavily bureaucratic and ineffective government with rapid (and outdated) industrialisation and large work force classed as peasants.

- Russian revolution of 1905 after the disastrous war against Japan. Nothing improved, Russian people were unhappy at the turn of the century.

- Wanted Slavic nationalism in the Balkans to establish its own influence and wanted to prevent Austia-Hungary expansion.

Turkey

[edit | edit source]- Turkey was the 'sick man of Europe' whose regime was corrupt and ineffective.

- Many revolts by nationalist and Islamic groups could not be contained and its weakness was exploited for commercial interest by other European powers.

- The Sultan was overthrown in 1909 by the "Young Turks" a group who wished to modernise Turkey.

- Many European Powers saw the slow decay of the Ottoman empire a threat as a result of the "power vacuum" that would occur.

- Emphasis on modernising and promotion of self-government was to occur. Austria-Hungary did not like this.

Long-term causes of World War I

[edit | edit source]Bismarck's web of alliances

[edit | edit source]- After its economic, military, and imperial potential, many powers in Europe began to feel nervous.

- Germany had to consolidate its new position in Europe, and Germany's chancellor Otto von Bismarck wanted to create a web of alliances to protect Germany from future attack.

- The Three Emperors' League (1887) or Dreikaiserbund joined Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary.

- The Dual Alliance (1879) helped fix the collapsed Dreikaiserbund after Russia came into conflict in the Balkans with Austria-Hungary.

- The Three Emperors' Alliance (1881) renewed the Dreikaiserbund with Russia.

- The Triple Alliance (1882) allied Germany with Austria-Hungary and Italy.

- The Reinsurance Treaty (1887), much like the Dual Alliance, served to piece together problems after problems in the Balkans in 1885.

The New Course and Weltpolitik

[edit | edit source]- The young and ambitious new Kaiser Wilhelm II and new chancellor Leo von Caprivi took German foreign policy on a 'new course' that would destroy Bismarck's web of alliances.

- German policy makers from the mid 1890s began to look beyond Europe in the hope to make Germany a colonial power with an overseas empire and navy.

- Such policies would divert German population away from social and political problems at home.

Imperialism

[edit | edit source]- One of the major causes of tension between the European powers in 1880–1905 was colonial rivalries.

- The effort of building their empires was initially driven by economic motives (cheap raw materials, new markets, low-cost labour).

- Over time, however, it became a mixture of Social Darwinism.

The emergence of the Alliance System

[edit | edit source]- Weltpolitik brought Germany in to trouble and Admiral von Tripitz, Secretary of State for the Navy shared the Kaiser's beliefs.

- von Tripitz thought Germany should mount a naval challenge to Britain, and pushed the Naval Law through the Reichstag.

- Britain's position of Splendid Isolation was no longer appropriate or useful, and sought security through Alliances as a result of its threat to its naval supremacy.

- After Russia, France, and Britain were joined together in the Triple Entente, Germany was 'encircled'.

- Europe was now divided into two main alliance systems; the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance.

The naval race

[edit | edit source]- Britain's threat lead to the launch of a super-battleship known as the HMS Dreadnought.

- The irony of its creation was that it nullified Britain's historical naval advantage as it made all other British battleships obsolete.

- Competitors began constructing similar ships and this triggered a 'naval scare' in the winter of 1908–09.

- The naval race changed the mood in Britain, and as Normal Lowe observes, Britain's willingness to go to war in 1914 owed a lot to the tensions generated by the naval race.

The situation in the Balkans

[edit | edit source]- The Balkans was a very unstable area that contributed to the tension in Europe before 1914.

- Turkey, once ruler of the entire Balkans, was now impotent, and many Serbs, Greeks, and Bulgars had already revolted and set up independent states.

- The Austrians lost grip of their multi-ethnic empire, and Slavs within the country wanted to break away. Serbia was thus seen as a threat to Austria-Hungary.

- Russia saw itself as the champion of the Slav people and wanted the straits of Constantinople to be kept open for ships to move from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea.

- A tariff war began in 1905–06 that dragged France in for financial support. The new Russophile King Peter believed an aggressive foreign policy would demonstrate that Austria still had power.

Short-term causes: the crisis years (1905-13)

[edit | edit source]The First Moroccan (Tangier) Crisis (1905)

[edit | edit source]- Germany was worried by the new relationship between Britain and France and set to break it.

- As part of the entente, Britain supported a French takeover of Morocco in return for France recognising British Egypt.

- Germany had not gained notable concessions in North Africa, which was a failure for Weltpolitik and a blow for German pride.

- Germany had not undermined the Entente Cordiale - they had strengthened it.

- Several states had considered war as a possible outcome of the crisis, thus signalling an end to the relatively long period of peaceful relations in Europe.

- Germany was now seen as the key threat to British interests.

The Bosnian Crisis (1908)

[edit | edit source]- Following the Tangier Crisis, the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907 was signed which confirmed conspiracy of 'encirclement' around Germany.

- This fear force Germany and Austria-Hungary into a closer relationship.

- An internal crisis in the Ottoman Empire led Austria-Hungary to annex two provinces of Bosnia, which outrage in Serbia, that caused Germany to stand 'shoulder to shoulder' with its Ally, and recognise the annexation.

- Russia, which had supported Serbia, suffered another international humiliation following its defeat from Japan. This meant that Russia was unlikely to back down from another crisis, in order to retain political stability and international influence.

- Russia began rearming.

- The alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary appeared stronger than commitments of the Triple Entente.

- Germany had opted to encourage Austro-Hungarian expansion.

The Second Moroccan (Agadir) Crisis (1911)

[edit | edit source]- Germany misinterpreted a French move in suppressing a revolt that had broken out in Morocco as a takeover; hence making ambitious and assertive claims that was popular back in Germany.

- Germany's 'gunboat diplomacy' was seen as a threat of war by Britain, and David Lloyd George gave a speech (the Mansion House Speech) to warn Germany off.

- Germany received two strips of the French Congo and increase the tension and hostility between Germany and Britain.

- German public opinion was hostile to the settlement and critical of their government's handling of the crisis; a failure of Weltpolitik.

- The entente between Britain and France was again strengthened.

The First Balkan War (1912)

[edit | edit source]- The Balkan League, forced by the Russians and consisting of Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro, sought to force Turkey from the Balkans by dividing Macedonia.

- Turkey was already weak as a result of the war between Italy over Totalitarian.

- Austria could not accept a stronger Serbia, and Russia would support its ally.

- The nervous Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary, managed to execute the Balkan Leagues goal and contain Austria-Hungary.

- This agreement, however, still caused resentment.

The Second Balkan War (1913)

[edit | edit source]- Due to the spoils of the First Balkan War, a second war broke out in July 1913.

- The Bulgarians felt as though there were to many Bulgarians living in Serbia and Greece, and thus attacked.

- Serbia was again successful. This fact encouraged the already strong nationalist feeling within Serbia.

- Serbia had doubled in size as a result of the two Balkan wars.

- Serbia had proved itself militarily, and had an army of 200,000 men.

- Serbia's victories were diplomatic success for Russia, and encouraged Russia to stand by its ally.

- Austria-Hungary was now convinced that it needed to crush Serbia.

- By association, the outcome of the two wars was a diplomatic defeat for Germany, which now drew ever closer to Austria-Hungary.

The international situation by 1913

[edit | edit source]- The crises of 1905-13 had seen a marked deterioration in international relations.

- Each crisis had passed without a major European war, nevertheless increased tension between the two alliance blocs in Europe and also created greater instability in the Balkans.

- War was by no means inevitable at this stage, however.

Other developments, 1900-13

[edit | edit source]The will to make war

[edit | edit source]- Literature, the press, and education portrayed war as short and heroic.

- Nationalism had become aggressive in major states, and this trend was encouraged by popular press, which exaggerated international incidents.

- James Joll indicated that "the reactions of ordinary people in the crisis of 1914 were the result of the history they had learnt at school".

The arms race and militarism

[edit | edit source]- Between 1870 and 1914, military spending by European powers increased by 300 percent.

- Although some attempts were made to stop arms build-up, for instance, the conference of The Hague in 1899 and 1907.

- However, no limits on production or war practices were agreed upon.

War plans

[edit | edit source]- Every European power made detailed plans regarding what to do should war break out.

- Reading: The Von Schlieffen Plan from the Open University

The immediate causes of the war: July Crisis (1914)

[edit | edit source]- There was optimism that should another conflict in the Balkans erupt, it would be contained locally.

- Archduke Franz Ferdinand, symbol of the Austria-Hungarian regime, was assassinated on the 28th of June 1914, by Gavrilo Princip, part of the Black Hand movement.

- Germany came to Austria-Hungary's assistance, and issued a blank cheque on the 5th of July 1914, that guaranteed unconditional support.

- Austria-Hungary took the opportunity to impose a severe ultimatum on Serbia a month later; hence seeming calculated.

- Serbia accepted all but one term of the harsh ultimatum, however, Austria-Hungary claimed it was too late and declared war on Serbia.

- Russia ordered a general mobilisation (for intimidation and preparation) on the 30th of July; causing Germany to declare war on Russia, and France (upon demands for neutrality that were rejected).

- Germany passed through Belgium to attack France, Britain upheld the 1839 treaty with Belgium and declared war on Germany.

What was the contribution of each of the European Powers during the July Crisis to the outbreak of war?

[edit | edit source]Germany

[edit | edit source]- The Kaiser had encouraged the Austro-Hungarians to seize the opportunity to attack Serbia on the 5th of July with the Blank Cheque.

- Russia's military modernisations were increasing the country's potential for mobilisation, and this would undermine the Schlieffen Plan.

- German generals, such as von Moltke believed that it was a favourable time for war.

- War would provide a good distraction, and unifying effect, to overcome rising domestic problems in Germany.

- War would improve the popularity of the Kaiser.

- John Lowe observed that Russia did not want a major war, and its mobilisation was a sign for preparation rather than the declaration that Germany had misinterpreted.

Austria-Hungary

[edit | edit source]- Austria-Hungary exaggerated the potential threat of Serbia and saw the assassination as an opportunity to 'eliminate Serbia as a potential factor in the Balkans'.

- It delayed its response to Serbia, and added tension to the July Crisis.

- It was the first to declare war on Serbia on the 28th of July.

- It refused to halt its military actions though negotiations with Russia were scheduled for the 30th of July.

Russia

[edit | edit source]- Russia wanted to prove itself after its defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, it acted as an ally to support Serbia; thus not restrain Serb nationalism.

- Its mobilisation triggered a general European war.

France

[edit | edit source]- After its ignominious defeat in 1871, it did not want to provoke a general war.

- France was swept into a war, and did not have any say.

Britain

[edit | edit source]- Luigi Albertini argues that Britain should have never made it clear it would stand 'shoulder to shoulder' with the French which may have deterred the Schlieffen Plan.

- Britain should have made its position clear during the July Crisis.

- John Lowe points out that Britain's talks with Russia in 1914 confirmed Germany's suspicion of a "ring of encirclement".

Historiography

[edit | edit source]- The German Foreign Office was already preparing documents from their archives attempting to prove that all belligerents states were to blame.

- Other governments felt the same urge and produced their own volumes of archives.

- Lloyd George, writing in his memoirs in the 1930s, explained that "the nations slithered over the bring into the boiling cauldron of war."

- S. B. Fay and H. E. Barnes were two American historians who supported the revisions arguments put forward by Germany regarding the causes of World War I.

- Luigi Albertini wrote a thorough and coherent response to the revisions arguments in the 1940s and put forward Austria-Hungary and Germany as responsible for war in the immediate term.

Fritz Fischer

[edit | edit source]- Fischer's argument focused the responsibility on Germany.

- He discovered the September Programme written by German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg, dated 9th of September 1914, which described Germany's aims for dominating Europe.

- He also indicated that the War Council of 1912 proved that Germany planned to launch a continent war in 1914, where von Moltke had indicated "war is inevitable and sooner the better."

- Fischer's argument is persuasive as he links longer-term policies from 1897 to short- and immediate-term actions in the July Crisis.

- However, Fischer's arguments have been criticised as a result of his limited evidence of the December War Council.

- Furthermore, it can be argued that German policy lacked coherency in the decade before 1914.

After Fischer

[edit | edit source]- Conservative German Historian Gerhard Ritter rejected Fischer's view in the 1960s.

- Immanuel Geiss Defended Fischer by publishing his own book of German documents undermining the revisionist arguments in the 1920s.

- Ruth Henig indicated that German desire to profit diplomatically and militarily from the crisis widened its containment from an Eastern Europe one to a continental and war.

John Keegan

[edit | edit source]- War was not inevitable despite the long- and short-term tension in Europe.

- The key to Keegan's theory is the lack of communication during the July Crisis.

- He indicates that Austria-Hungary wanted to punish Serbia, but lacked the courage to act alone, and this was not communicated.

- Also, Germany had wanted diplomatic success that would leave Austria-Hungary a stronger ally. Germany, also, did not want a full European war.

- Russia only wanted to support Serbia

- France did not mobilise and was worried about Germany

- Britain only awoke to the dangers of the July Crisis on the 25th of July, and hoped Russia could tolerate Serbia's punishments.

- The Serbs had been forgotten after the incompatible nations began to break the tangled web of alliances.

James Joll

[edit | edit source]- Joll suggests an atmosphere of intense tension was created by impersonal forces in the long- and short-terms with the personal decisions made in the July Crisis that led to war.

- Personal expansionist aims versus capitalism.

- Various war plans as developed by governments versus international anarchy.

- Calculated decisions versus alliances.

Niall Ferguson

[edit | edit source]- Ferguson suggests that Germany was moving away from militaristic tenancies prior to World War I.

- He argues that German Social Democrat Party was on a rise and that influenced the Kaiser's regime.

- Britain had misinterpreted German ambitious and decided to act on impede German expansionism.

- War was not inevitable in 1913, despite militarism, imperialism, and secret diplomacy.

II. Practices of World War One and their impact on the outcome

[edit | edit source]Types of war: World War One as a Total War

[edit | edit source]Land warfare- the Western Front

[edit | edit source]Failure of the Von Schlieffen Plan

[edit | edit source]As you read above, the Von Schlieffen plan was bold and ambitious and despite initial success, it also soon ran into trouble. Intended to knock the French out of the war quickly, the German advance through Belgium triggered British involvement in the war ostensibly to protect Belgian neutrality. It seems likely however that for the British there were other motives in getting involved, specifically a German victory in the west would have been too threatening to British imperial interests. The German advance was slowed by fierce resistance in Belgium and by sheer exhaustion as once troops left railway lines they were able to move no faster than Julius Caesar's legions in their conquest of Gaul. With German supply lines stretched and the professional soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) able to delay further German troops at the Battles of Mons on 23 August, the Schlieffen plan's aim of a quick knock out blow of the French was now looking less and less likely. The plan's final failure came as the German army's advance was halted and then reversed by the combined French and British counterattack along the Marne River in early September.

Video: The Failure of the Von Schlieffen Plan

Race To the Sea

[edit | edit source]After the Battle of the Marne, both sides began to dig trenches to provide shelter for their troops. After attempts to break through the German lines failed both sides rushed to outflank each other and in particular gain control of the channel ports. This "race to the sea" ended in stalemate with more permanent trenches being dug to protect troops from artillery. These networks of trenches would dominate the war on the Western Front.

Video: Belgian resistance and the race to the Sea

Trench Warfare/Deadlock on the Western Front

[edit | edit source]

Trench warfare developed very quickly on the western front and soon the war of manoeuvre had become a grinding war of attrition. Huge complexes of trenches soon stretched over western Europe from 1914–1918 as both sides constructed elaborate trench networks, underground tunnels, and elaborate dugout systems facing the enemy. The trenches were typically protected from assault by barbed wire which slowed the advance of attacking forces and left them vulnerable to machine gun fire. The area between opposing trench lines (known as "no man's land") was fully exposed to artillery fire from both sides. Attacks, even if successful, often sustained severe casualties. The deadlock would not be broken until more advanced technology and tactics such as the use of combined arms were developed throughout the war.

Website: The Imperial War Museum has lots of super resources and artefacts on Trench Warfare here.

Task: Trench Warfare

[edit | edit source]- Examine the 10 photographs from the Imperial War Museum of trench life in WW1 , then create a Cornell notes on Trench Warfare. Once you've finished go back to the photographs and see if you've missed any details, then add those details in. Make sure you use your own knowledge and not just what's in the photographs. Now add questions that you may still have to the section on the left of your paper. Lastly complete a summary.

Historiography: Historian Hew Strachan on Trench warfare

[edit | edit source]“Trenches created health problems but they saved lives. To speak of the horror of the trenches is to substitute hyperbole for common sense: the war would have been far more horrific if there had been no trenches. They protected flesh and blood from the worst effects of the firepower revolution of the late nineteenth century….The dangers rose when men left the embrace of the trenches to go over the top, and when war was fluid and mobile.”[2]

- What does Professor Strachan argue about trenches?

- Is his view a positive or a negative one about trenches, explain your reasoning

Video: Historian Dan Snow on trench warfare

[edit | edit source]- Watch these two videos from Dan Snow, video A and video B,

- Which aspects of the videos support Professor Strachan's points about trench warfare ultimately saving lives?

The Battle of the Somme

[edit | edit source]Historiography: Historian Gary Sheffield on the first day of the Somme

[edit | edit source]"The British artillery were set three main tasks: cutting the barbed wire in front of the German positions with shrapnel; the destruction of German trenches; and counter-battery work, that is destroying or at least neutralizing the German artillery. The watching infantry were impressed by the power of the bombardment. ……..On much of the front, however, the bombardment was visually impressive but was ultimately unsuccessful. Banks of barbed wire remained uncut; German trenches, although battered, still contained determined groups of defenders; and sufficient German artillery survived the counter-battery work to inflict dreadful casualties on the attackers."[3]

- What were the British intending to do?

- What had not gone according to plan for the British?

Historiography/ Perspectives: Were lions led by Donkeys during WW1?

[edit | edit source]A bit part of IB History is challenging and critiquing multiple perspectives of the past, and to compare them and corroborate them with historical evidence. While it is the case that for every event recorded in the past, there are invariably multiple contrasting or differing perspectives one of the most interesting examples of this in the context of WW1 is the Lions led by Donkeys question which is the popular idea that the Lions, the ordinary soldiers were led to their deaths by the Donkeys, the generals of WW1. This gives rise to many different inquiry questions around the theme of "Were Lions led by Donkeys in WW1?" Some different perspectives and tasks are below:

Perspective 1: The Blackadder/Popular culture idea -Lions were led by Donkeys

[edit | edit source]- Task: Watch this famous clip from comedy series Blackadder. Analyze how it portrays Fieldmarshall Haig and by extension the other generals of the war

- Task: Read this alternative view on the WW1 Generals from a professional Historian. How does it contrast with the popular view?

- Task: Now explore the issue further and generate your own view (this is also a great intro for a debate style task) sources and worksheets from the national archives are here and there's more here including an extract from the alternative view above.

Operation Michael

[edit | edit source]

Historiography: Historian Nigel Jones on German Tactics during Operation Michael

[edit | edit source]“The stormtroopers were trained to move in small groups across the battlefield, probing for the enemy’s weakest points like a surgeon’s knife. Any strongpoints were avoided; the stormers merely skirted them and pushed onwards, leaving the essential but unglamorous mopping up to the humble infantry trailing in their wake. The stormers sped gloriously ahead, moving fastest and furthest, set apart from their former comrades even in the hottest moments of action. This conscious separation only served to further heighten the stormers’ sense of being a chosen order destined to conquer and rule. The German armies, with their stormtroop vanguard, accomplished much in the series of great offensives launched by Ludendorff. The first, codenamed ‘Michael’, on 21 March, put the British Fifth Army to inglorious flight, bit out a great chunk of territory and almost succeeded in severing the British from the French. The second blow, Operation ‘Georgette’, struck the following month over the blasted old battlegrounds of Flanders and drove the British back to within sight of the Channel. A third offensive – ‘Blücher’ – let loose at the end of May, utterly broke the Franco-British forces along the Aisne, and brought the Germans, as in 1914, back to the banks of the Marne and within artillery range of Paris.”[4]

- What new tactics did the German Army develop for Operation Michael?

- What evidence is there that these new tactics were successful (at least initially)?

The 100 days

[edit | edit source]The 100 days was the Entente counterattack after Operation Michael/The Ludendorff offensive. The Ludendorff offensive had left the German military exhausted and exposed and beginning with skillful use of surprise and combined arms at the 1918 Battle of Amiens, the Entente counterattack was savage, relentless and ultimately broke the back of the German army. You can read more about combined arms and technological developments below.

Video: The Battle of Amiens from the BBC

Historiography: Historian Nick Lloyd on British tactics at the Battle of Amiens 1918

[edit | edit source]“8 August would be one of the most remarkable days of the war. Although the position of all units was not known, the Allied assault had driven between six and eight miles into the German lines, shattering Second Army and unhinging the flank of Eighteenth Army on its left. German casualties had been staggering. The official history estimated that they were as high as 48,000 men, including 33,000 missing or taken prisoner. Four hundred guns had been lost as well as hundreds of machine-guns and trench mortars. For the battalions in the front line, often only small groups of survivors remained. 41st Division, which had faced the Australians opposite Villers-Bretonneux, was almost wiped out. It had lost all but three of its guns, and little remained of its front and supporting battalions. Equally unnerving was the sight of the survivors from the opening attack. Numerous front-line battalions had been reduced to the size of companies. All that remained were clusters of shell-shocked men; their will utterly broken; their faces grimy; their eyes glassy, staring straight ahead. Their stories were always the same: horrifying accounts of iron monsters clanking out of the mist towards them; of mass infantry attacks; of being cut off and surrounded; of waiting for counter-attacks that never came. Some did not – or perhaps could not – say anything at all. Ludendorff’s worst nightmare was, it seemed, coming true.”[5]

- Explain why the 8th August 1918 was such a bad day for the German army?

- What evidence is there from the passage above that by 1918 warfare on the Western front was no longer static?

Technological developments

[edit | edit source]Historiography: Historian John Bourne on technological developments on the Western Front from 1914-1918

[edit | edit source]“In 1914 the British soldier went to war dressed like a gamekeeper in a soft cap, armed only with rifle and bayonet. In 1918 he went into battle dressed like an industrial worker in a steel helmet, protected by a respirator against poison gas, armed with automatic weapons and mortars, supported by tanks and ground aircraft and preceded by a creeping artillery barrage of crushing intensity. Firepower replaced manpower as the instrument of victory. This represented a revolution in the conduct of war.'”[6]

- What had changed since 1914 for the infantry soldier?

- How were the infantry used in combination with other parts of the military (combined arms)?

Historiography: Historian Gary Sheffield on technological developments on the Western Front from 1914-1918

[edit | edit source]"The problem was that in 1914 tactics had yet to catch up with the range and effectiveness of modern artillery and machine guns. Warfare still looked back to the age of Napoleon. By 1918, much had changed. At the Battle of Amiens on 8 August 1918, the BEF put into practice the lessons learned, so painfully and at such a heavy cost, over the previous four years. In a surprise attack, massed artillery opened up in a brief but devastating bombardment, targeting German gun batteries and other key positions. The accuracy of the shelling, and the fact that the guns had not had to give the game away by firing some preliminary shots to test the range, was testimony to the startling advances in technique which had turned gunnery from a rule of thumb affair into a highly scientific business. Then, behind a 'creeping barrage' of shells, perfected since its introduction in late 1915, British, French, Canadian and Australian infantry advanced in support of 552 tanks. The tank was a British invention which had made its debut on the Somme in September 1916. Overhead flew the aeroplanes of the Royal Air Force, created in April 1918 from the old Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service. The aeroplane had come a long way from its 1914 incarnation as an extremely primitive assemblage of struts and canvas, its task confined to reconnaissance."[7]

- Why was there a mismatch between military tactics and modern technology in 1914?

- What could British artillery do by 1918?

- What was a "creeping barrage"?

- From the extract what examples of "combined arms" can you find?

Video: Development of tanks in WW1 from the BBC

Land warfare-the Eastern Front

[edit | edit source]Battle of Tannenberg

[edit | edit source]Brusilov Offensive

[edit | edit source]Naval warfare: Technological Developments

[edit | edit source]The Battle of Jutland

[edit | edit source]Development of Q Ships

[edit | edit source]Unrestricted Submarine Warfare

[edit | edit source]Historiography: Historian Hew Strachan on the German decision to engage in unrestricted submarine warfare

[edit | edit source]“Scheer was not prepared to accept such passivity, and after Jutland his assertion that the submarine was the most obvious weapon with which to strike Britain gained in stridency. He now had powerful support from the army. Falkenhayn had proposed a U-boat campaign against Britain to accompany his attack on France at Verdun, and when Hindenburg and Ludendorff replaced him they, too, accepted that economic warfare, not direct confrontation on the battlefields of France and Flanders, was the way to tackle Britain.”[8]

- How did the Battle of Jutland change the German naval strategy?

- What was the ultimate aim of this new strategy?

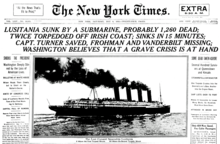

The Sinking of the Lusitania

[edit | edit source]

In May 1915 the ship Lusitania was returning from New York to Liverpool with 128 US citizens on board when she was sunk by a German U-Boat without warning. The Germans felt fully justified in this as she was carrying munitions to help the British war effort. While this sinking did not lead directly to American entry into the war on the Entente side, it certainly did play a role in turning American public opinion against the Germans.

Website: The US Library of Congress has a host of Lusitania resources here.

Convoy system

[edit | edit source]The Royal Navy developed convoy tactics in 1917 in order to see off the U-Boat threat after the Germans began their campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare. It worked by providing escort vessels for groups of ships. The escorts dropped depth charges in areas where German 'U-boats' were known to operate and engaged U-Boats when they surfaced to fire as at this point technology had not developed enough for U-Boats to fire at shipping while under water.

Historiography: Historian Alexander Watson on convoy tactics

[edit | edit source]“Nonetheless, if convoys did not eliminate the U-boat threat, they were the key factor in retarding it so significantly. The convoys not only emptied the seas of easy targets by concentrating and protecting shipping but they themselves proved unexpectedly difficult for submarines to locate. Between October and December 1917 just 39 of the 219 Atlantic convoys that sailed were even sighted by submarines. Their low detection rate was a consequence not just of the vastness of the seas but also of the British Admiralty’s ability to reroute the ships around danger. Warships, unlike most merchantmen, had powerful wirelesses, which could receive messages from London about the location of U-boats based on sightings or the interception of their radio communications. The Germans found no answer to this problem.”[9]

- Explain how the introduction of convoy tactics helped neutralize the U-Boat threat in WW1?

- How was technology used to neutralise the U-Boat threat?

Historiography: Historian B.J.C. McKercher on the failure of the U-Boat campaign to starve Britain

[edit | edit source]“Beginning in February 1917, German submarines conducted the kind of operations envisaged by Ballin and others two years before. Through the spring and summer of 1917, this German offensive saw mounting shipping losses for Britain and its allies—1,505 merchantmen (2,775,406 tons) in six months. However, supported by the United States navy, the Royal Navy responded with effective defensive measures: heavily protected convoys, improved employment of depth charges and mines, air cover, and better use of intelligence. By late 1917, although the British had to ration food, and some basic commodities were in short supply, Germany’s ability to disrupt allied economic life via the submarine offensive abated (617 sinkings in five months). Attacks on allied shipping continued into 1918 with limited effectiveness, but the Central Powers had lost this critical element of the economic war by the time the Germans forced the Bolshevik Russian regime to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and embarked on their great, and ultimately unsuccessful, offensive in 1918.”[10]

- What evidence is there that the U-Boat campaign was initially successful?

- How did the British and Americans respond?

- How successful was the response?

British Naval Blockade of Germany

[edit | edit source]Historiography: Historian B.J.C. McKercher on the success of the British naval blockade of Germany

"Allied success is undeniable. For instance, before the war, the weekly per capita German urban consumption of meat was 2.3 pounds; by 1917–18, it fell to 0.3 pounds. Additionally, the number of German civilian deaths attributed to the blockade in 1915 was 88,235 (9.5 per cent above the 1913 total); by 1918, this figure had climbed to 293,000 (37 per cent above the 1913 total). There is controversy about whether the German people actually starved during the war, especially in the difficult winter of 1917–18. The argument is made that weight loss results in a demand for less food and that, when the body adjusts, it can be made to work as hard as ever. In all of this, moreover, it must be admitted that between 1914 and 1918, the blockade impaired little the fighting efficiency of the German armed forces. But the blockade had a social and psychological and, therefore, a political impact on Germany. As General Kuhl, a senior staff officer, argued: ‘Many things combined to bring down the German people...but I consider the blockade the most important of them. It disheartened the nation.’ Economic hardship was one factor that saw many Germans become critical of their government after 1915. Disparities existed in the distribution of food and necessary commodities. For instance, rural areas had reasonable supplies of food, whilst urban areas did not. Within cities, disparity also existed between and within classes. Those people with money or political influence could obtain products on the black market. Within the working class, armament workers were better provided for than unskilled workers, white-collar workers, and even minor government officials. Public discomfort grew as a range of ordinary consumer goods like woollen blankets and leather shoes were in short supply and German prices inflated because of scarcities; over fifty food riots occurred in Germany in 1916, a number that increased in 1917–18. Along with food rationing—the harsh winter of 1917–18 compounded German unease—the impact of the blockade played a part in the revolution of November 1918 that led to the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the advent of the Weimar Republic."[11]

- McKercher says that the blockade didn't really impair the fighting efficiency of the German armed forces. Why then does he consider the blockade such a success?

- How does McKercher deploy primary source evidence to illustrate his point?

Air warfare: Technological developments

[edit | edit source]Video: Dan Snow on the development of air technology during WW1

Historiography: Historian Gary Sheffield on the development of airpower during WW1

“By 1916 battles were fought in three dimensions, and this was the year that airpower came of age. Before the war, military aviation had largely been seen as the preserve of a few specialists. Some senior commanders had been dismissive of the military potential of the aeroplane. The emergence of trench warfare opened the eyes of most of the doubters. Aeroplanes could fulfil the role that was now denied to the traditional instrument of reconnaissance, cavalry. More than that, as it became clear that the battlefield was dominated by artillery, aircraft proved highly useful in spotting for the gunners: indicating the fall of shot, and thus improving the accuracy of artillery fire. During 1915 various techniques associated with this new role were developed, key among them photographing the enemy trenches and interpreting the resulting images, and establishing wireless communications between air and ground. So valuable was aerial reconnaissance that aircraft, mostly unarmed at the outbreak of war, spawned a type that would later be termed fighters, which sought to prevent enemy observation aeroplanes from crossing friendly lines, or to protect friendly machines in their role of observation. Thus a battle for control of the air began to develop.”[12]

- Explain how the role of aircraft developed during WW1?

- Explain how aircraft were used in combination with artillery during WW1?

Historiography: Historian Nick Lloyd on allied use of airpower during the Allies hundred days offensive at the end of the war

“The constant Allied air attacks gnawed away at morale even further. German columns of infantry, marching to the front, would regularly have to scatter as British and French biplanes swooped low overhead, firing machine-guns and dropping bombs. Although the physical damage that such aircraft could do was undoubtedly limited (with only 25lb bombs), its effect on tired and nervous soldiers can well be imagined.”[13]

- Explain how aircraft were used during the 100 days?

- What evidence is there from the passage that despite the technological advances, aircraft only played a supporting role during WW1?

The extent of the mobilization of human and economic resources

[edit | edit source]The influence and/or involvement of foreign powers

[edit | edit source]World War 1 was a global war both in terms of the participants and where it was fought. This task puts the global dimension in perspective.

Task: Use this interactive map of WW1 to explore the geographic spread of WW1.

- Select an area on the map to find countries and territories from that region.

- Navigate through the menu to read about battles, life on a country’s or colony’s Home Front

Involvement of imperial and colonial forces

[edit | edit source]Video: Historian David Olusoga on the global soldiery of WW1

Video: Historian David Olusoga on the forgotten soldiers of WW1

Video: India and the Great War

Gallipoli

[edit | edit source]Japan and Germany's Asian possessions

[edit | edit source]China and the Western Front

[edit | edit source]While the Chinese did not send front line troops, they did send labourers to the western front who did play an important role both in terms of logistics and in freeing up European and imperial troops to fight on the front lines. China hoped by being on the winning side they would receive fairer treatment from the imperial powers after the war particularly with regards to receiving back Germany's Chinese possessions stolen from China in the previous century. This was not to be the case and at the Paris Peace Conference the Chinese delegation walked out of the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in protest.

World War One in East Africa

[edit | edit source]Website: The British Library has extensive resources on WW1 in East Africa here. With a suitably strong research question this would be an excellent topic for the student selected Internal Assessment research task

American entry to the War

[edit | edit source]Initially America pursued a policy of neutrality in the war. However, the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, and in particular the sinking of the Lusitania and a very clumsy German espionage attempt you can read about below, led to America joining the war on the Entente side in 1917. It has been suggested that in part the reason for the timing of the last great German offensive of the war, Operation Michael (also called the Ludendorff offensive) was in order to defeat Britain and France before the arrival of fresh American troops in large enough quantities to turn the tide of war completely against Germany.

The Zimmerman telegram

[edit | edit source]The discovery and publication of the Zimmermann Telegram played a crucial role in generating American public support for the entering the war on the side of the Entente forces. The Telegram itself was a top secret diplomatic communication issued from the German Foreign Office in January 1917 proposing a military alliance between Germany and Mexico if the United States entered World War I against Germany. In exchange for their intervention, Mexico would recover Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. In a stunning intelligence coup, British Naval intelligence intercepted and decoded the telegram before releasing it to the Americans. Honestly if naively, German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann publicly admitted on March 3 that the telegram was genuine further enraging American public opinion and in turn generating support for the American declaration of war on Germany on April 4th 1917.

Review questions: The influence and/or involvement of foreign powers

[edit | edit source]- What contribution did imperial and colonial forces make to the war?

- To what extent is it accurate to describe WW1 as a World War?

- What evidence is there that the role of imperial and colonial forces has been underrepresented?

- What role did the Indian army play on the Western front?

- Why is there a Chinese war grave in France? What did China contribute to war effort?

- What role did Japan play in the war?

- Who were the ANZACS?

- Why did the Gallipoli campaign of 1915 fail?

- Why did the United States join the war?

- How important to the outcome was the entry in 1917 of the United States of America to the war?

The Armistice

[edit | edit source]While not a formal diplomatic end to the war, the Armistice of 11 November 1918 signaled the end to the fighting between the allies and Germany. Previous armistices had already been signed with Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire so this was the last one. The armistice came into force at 11:00 a.m. Paris time on 11 November 1918 hence the special significance of the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month. As well as an end to the fighting, the armistice terms included the withdrawal of German forces from west of the Rhine, the surrender of aircraft, warships, and military equipment, the release of Allied prisoners of war and interned civilians, as well as provision for future reparations. In light of the stabbed in the back myth, it is worth emphasizing that this was very much not a neutral agreement and signaled a defeat for Germany. This can be seen in the fact there was no release of German prisoners and no immediate relaxation of the British naval blockade of Germany which as you read above was causing real suffering to the German people. Particularly tragically, fighting continued right up to 11 o'clock on Armistice day, with 2,738 men dying on the last day of the war.

Task: Website Activity

[edit | edit source]Practices of WW1 Review Questions

[edit | edit source]- What type of war was WW1? What made it so?

- What is a war of attrition?

- What is a war of maneuver?

- Why did the Von Schlieffen plan fail?

- What was the race to the Sea?

- Why did the Battle of the Marne matter?

- Which was more important in causing the failure of the Schlieffen Plan, the changes to the Plan or the actions of the British Expeditionary Force? Explain your answer

- Why did the race to the sea lead to stalemate on the Western front?

- How and why did trench warfare develop?

- Describe how trenches were constructed

- What was living in a trench like?

- Why was there such a high number of casualties in the First World War?

- What was an artillery bombardment?

- How can it be argued that WW1 was a truly global war?

- Why was attacking across ‘no man’s land’ so difficult?

- How important was barbed wire as a reason for a prolonged war on the Western Front? Explain your answer.

- What was a creeping barrage?

- How did Germans use "stormtroopers" to attempt to break the deadlock?

- What were combined arms tactics?

- What was the 100 days offensive?

III. Effects of World War One

[edit | edit source]The successes and failures of peacemaking

[edit | edit source]Treaty of Brest-Litvosk

[edit | edit source]Treaty of Versailles

[edit | edit source]

Peace Treaties: Review Questions

[edit | edit source]- What problems faced the peacemakers in 1918?

- What were the other major peace treaties?

- What do the major provisions of the treaty of Brest-Litvosk (and Bucharest) imply about the likely nature of a similar peace treaty with France and Britain if Germany had won the war?

- What was Article 231 and why was it included in the Treaty of Versailles?

- Why did China refuse to sign the Treaty of Versailles?

- To what extent did the Treaty of Versailles create a Carthaginian peace?

- To what extent is the claim that the Treaty of Versailles did not go far enough supported by the evidence?

- Why were the peacemakers at Versailles so severe on Germany?

- Why did British Prime Minister Lloyd George favour a moderate peace settlement with Germany and why did Clemenceau disagree?

- ‘German reaction to the Treaty of Versailles was understandable.’ How far do you agree with this statement?

Territorial changes

[edit | edit source]Political impacts

[edit | edit source]Short-term

[edit | edit source]Russian Revolutions

[edit | edit source]Long-term

[edit | edit source]Economic impacts

[edit | edit source]Social impacts

[edit | edit source]Demographic impacts

[edit | edit source]Changes in the role and status of women

[edit | edit source]

Historiography: Historian Professor Susan R Grayzel on how WW1 Impacted Women's Daily Lives

[edit | edit source]“The scope and duration of the war meant that governments enlisted women in the war effort by reorganising basic aspects of their lives. By rationing, governments could alter the food women could obtain and eat; by imposing censorship, they tried to restrict the information they could know or share. The waging of the war placed enormous expectations upon able-bodied men in the prime of life to serve in the military and upon their female counterparts to contribute to the war effort in many ways, in addition to maintaining their domestic roles.”[14]

- What two examples of historical change does Professor Grayzel see WW1 causing for women?

- What one example of historical continuity from the prewar period does Professor Grayzel see for women during the war?

Historiography: Historians Cawood and McKinning Bell on employment of British women during WW1

[edit | edit source]"In Britain, the number of women employed increased from 3,224,600 in July 1914 to 4,814,600 in January 1918. Nearly 200,000 women were employed in government departments, with half a million becoming clerical workers in private offices and a quarter of a million working on the land. The greatest increase of women workers was in engineering. Over 700,000 of these women worked in the highly dangerous munitions industry.Whereas in 1914 there were 212,000 women working in the munitions industry, by the end of the war it had increased to 950,000. Christopher Addison, who succeeded David Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions, estimated in June 1917 that about 80 per cent of all weapons and shells were being produced by ‘munitionettes’. The work was extremely dangerous and accidents at munitions factories resulted in over 200 deaths in Britain alone. Others suffered health problems such as TNT poisoning because of the dangerous chemicals the women were using."[15]

- Which conclusions can be drawn from the statistics Cawood and McKinning Bell quote regarding female employment during WW1?

Historiography: Historian Professor Susan R Grayzel on how WW1 Impacted Cultural Change around Gender

[edit | edit source]“Cultural change may be the hardest to gauge. Certain norms of Western middle-class femininity all but disappeared, and women’s visible appearance before 1914 and after 1918 markedly differed – with many women having shorter hair and wearing shorter skirts or even trousers. New forms of social interaction between the sexes and across class lines became possible, but expectations about family and domestic life as the main concern of women remained unaltered. Furthermore, post-war societies were largely in mourning. The extent to which the process of rebuilding required the combined efforts of men and women in public and perhaps even more so in private shows the shared human toll of this extraordinary conflict.”[14]

- What one example of historical cultural change does Professor Grayzel see WW1 causing?

- What one example of historical cultural continuity does Professor Grayzel see WW1 maintaining?

Historiography: Historian Professor Susan R Grayzel on the overall impact of WW1 on the role and status of Women

[edit | edit source]“Because the war destroyed so many lives and reshaped the international political order, it is understandable to view it as a catalyst for enormous changes in all aspects of life, including ideas about gender and the behaviour of women and men. The messy reality of the lives of individual men and women is much harder to generalise about. There were visible changes in European politics, society, and culture but also a certain degree of continuity. Most notably, the aftermath of the war witnessed women gaining voting rights in many nations for the first time. Yet women’s full participation in political life remained limited, and some states did not enfranchise their female inhabitants until much later (1944 in France). Imperial subjects and racial minorities, such as those in the United States, continued to be unable to exercise their full political rights. Socially, certain demographic trends that were prevalent before the war persisted after it. Family sizes continued to shrink despite renewed anxiety about falling birth rates and ongoing insistence on the significance of motherhood for women and their nations. Economically, returning men displaced many women from their wartime occupations, and many households now headed by women due to the loss of male breadwinners faced new levels of hardship. Women did not gain or retain access to all professions, and they did not come close to gaining equal pay for comparable work.”[14]

- Why does Professor Grayzel argue that WW1's impact on voting rights for women was limited?

- Which specific evidence does she deploy to prove her point on voting rights?

- What other groups remained politically discriminated against after the war? Give an example from the passage.

- Which example of continuity around demographic trends does she give?

- Give example of how women were still disadvantaged economically after the war.

Effects of WW1 review tasks

[edit | edit source]Task: Research and discuss the social effects of World War I in at least two countries. Don't forget to cite your sources.

- How did ordinary people live, during and after the war?

- What changed?

Effects of WW1 review questions

[edit | edit source]- How far were the peace treaties a success?

- Why did Russia leave the war?

- What system of Government was in Russia by the end of the war?

- Why was the armistice signed?

- Why did revolution break out in Germany in October 1918

- How far did WW1 change the role and status of women?

- What was the impact of war on civilian populations?

- How far did the First World War have a positive effect on Britain’s civilian population?

- What economic and social changes arose after WW1?

- What happened to the Armenians?

- What were the immediate wider implications of the war for international relations?

- To what extend did World War I affect the social, political and economic status of women?

Exam style questions for practice