Hobo tourism/Overnight stays in long intercontinental journeys/In the company of homeless people

Staying overnight in homeless companies and communes is a method of obtaining a night's rest (and sometimes a short-term stay) practised by supporters of hobo tourism.

Why is it needed?

[edit | edit source]There may be several reasons for this seemingly strange accommodation option:

- Arrival in next city of exotic country coincided with the late time of day, when there is no option.

- A traveller sleeping in the company of homeless people may not be noticed by street criminals, whose activities become more active at night; but a foreigner sleeping alone on the street will be the object of unnecessary attention by criminals.

- People living on the streets and train stations can help a beginner in understanding of local traditions, for example, how to protect themselves from petty thieves who can covet seemingly worthless items, etc.

- Living in a commune of the homeless provides the traveler with opportunities to experience the life of the lower classes of the society.

- Sometimes the homeless community has a habitable structure (a ruin or unfinished building) where a proponent of the hobo tourism methodology can live for some time (read more below, in the "Practical Examples" section).

Comparing the method to "Slum tourism"

[edit | edit source]The Russian traveler Viktor Pinchuk, who uses unconventional methods of travelling, has repeatedly lived and stayed overnight in underclass and sometimes socially deprived places. As a rule, a foreign tourist who has lived side by side with beggars for some time, who is not opposed to them and has no privileges that elevate him above others, is respected by slum-dwellers without provoking negative emotions, and his visit does not leave an unpleasant residue in people's memory, which may appear after visiting narcissistic sightseers with expensive photo and video equipment.

Practical examples

[edit | edit source]This is how the books describes a traveller's encounter with the homeless in Indonesian capital:

Behind the decrepit fence — abandoned unfinished building: just the thing. Apparently, someone lives there. I called out. A young Indonesian with a confused expression came to the fence. Asked him by signs if I could come in. He pointed to the gate on the other side. It was opened. An elderly woman came out. "Can I sleep here?" — uttered a phrase in the local language, prudently learnt by heart. The old woman, smiling, permitted. The four-storey derelict building had no walls. Part of the ground floor was occupied by a commune of homeless people, the upper floors were empty. The guy took me to the second floor, where a spring mattress from a double bed lay on the concrete floor. Next to it was a wooden bench, like the ones they use in hospitals and on beaches, with a pile of rags on it. "You can cover yourself with this," the Indonesian explained and walked away. Of the "furniture" in the space allotted to me there — only the two items described, and there is a "toilet" that don't know its purpose yet. I approached the "balcony" (there were ones on four sides): a pile of rubbish below, in the distance the neon-lit buildings of expensive hotels [1].

Late in Surabaya, Indonesia:

...Leaving the bus, I walked a hundred metres, looking for a nook to sleep. The midnight street was lit by lanterns. On the left, under a long awning on the pavement, lay a community of homeless people who reminded me of their counterparts in the Indian city of Mumbai. I walked a little further — nothing suitable. However... Turned around and turned back. Perhaps the African natives would envy these people: they have electricity that is not always present in the Black Continent. I approached the two men sitting under the light bulb. The old man, hearing a question in his native language, shook head negatively and with a disgruntled expression on his face, asked to go back to where had come from. This was an odd reaction. Usually beggars in third-world countries are enthusiastic about such a request. In fact, who says this grandfather is the "boss" of the homeless? I'll ask others. At the very end of the "settlement" there were two more: a middle-aged man was sleeping on the ground, while a young man of indeterminate gender, with an earring in his ear, was watching... television. The mains cable from a small television receiver went somewhere upwards, probably to an electric pole. On closer inspection, the street television viewer turned out to be a man. "Everything here is occupied," — he explained with a smile, — and the empty lot in the corner is for the motorbike. "You can set up there," — the guy added, pointing to the threshold under the closed double door of the building a metre away from the motorway. Far from luxury, even by the standards of a bum, but at midnight there was no alternative. With an affirmative nod of my head, I spread out a mat and soon fell asleep to the lullaby of the occasional passing car [2].

And this is about an overnight stay in Guangzhou, China:

...On the lower span of the bridge, occupying a well-lit area behind the railings, the three were resting peacefully after a noisy day at the railway station. The older one, apparently mute, mooed only occasionally, the second, a middle-aged bum, was sullen and taciturn, and the youngest was slightly different from his brethren: he had not yet reach the standard. He was the one I asked about spending the night in their company. "No problem!" — he replied with a sign and, watching me spreading a mat, decided to instruct the guest. Passers-by squinted at this scene and, without stopping, walked on, spurred on by the overcast weather. Noticing that I looked at the clouds, the guy shook his head, "No, it's not going to rain." — "Shoes, just to be safe, you'd better put them under a pillow," — he explained, — "they'll get dragged away. "But my shoes is very old" — I replied, being quite surprised. "That's not the point," the instructor went on, "a beggar boy tramp (there are many of them here) might come up and ask for money, and if you don't give it, he'll grab the shoes and run away. — "And the backpack has to be wrapped around both arms and covered with a blanket," the homeless man explained, seeing me tie the strap to my arm. "Tying it won't save you, they might cut it off..." — he added. At this time the oldest of the two made a sound and my interlocutor approached him.[3].

Gallery

[edit | edit source]-

The second (vacant) floor of an unfinished building housing a community of homeless people. Jakarta, Indonesia. (Photo from book by Pinchuk Viktor "Six months by islands... and countries")

-

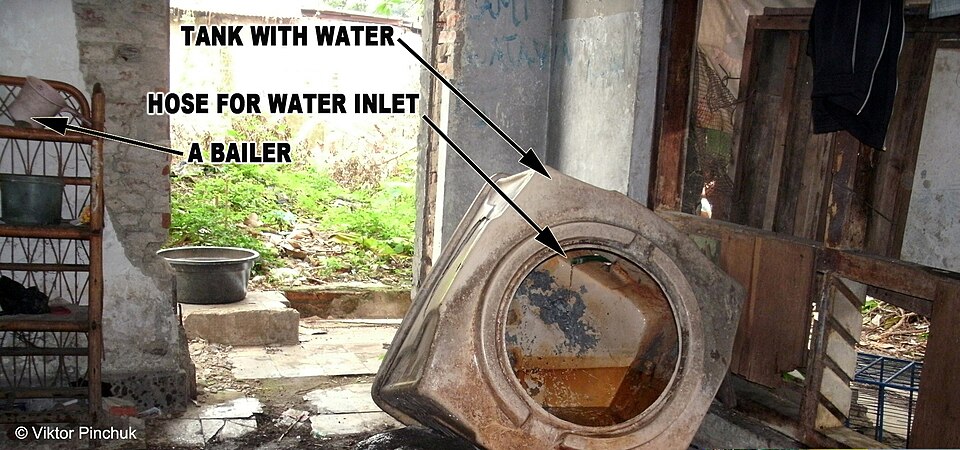

"Shower room" in an Indonesian commune of homeless people (Jakarta, Indonesia), which Russian traveller Viktor Pinchuk used with them.

-

One of the inhabitants of the railway station in whose company the Russian traveller spent the night; Guangzhou, China (Photo from book by Pinchuk Viktor "Six months by islands... and countries")

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Pinchuk, Viktor. Six months by islands... and countries (in Russian). Russia: Brovko. p. 64 - 65. ISBN 978-5-9908234-0-2.

- ↑ Pinchuk, Viktor. Six months by islands... and countries (in Russian). Russia: Brovko. p. 77 - 78. ISBN 978-5-9908234-0-2.

- ↑ Pinchuk, Viktor. Six months by islands... and countries (in Russian). Russia: Brovko. p. 157. ISBN 978-5-9908234-0-2.

Materials in Wikisource project

[edit | edit source]- Viktor Pinchuk "Notes of an international tramp"